Abstract

The current longitudinal study examined which individual symptoms of depression uniquely predicted a subsequent Major Depressive Episode (MDE) in adolescents, and whether these relations differed by sex. Adolescents (N=240) were first interviewed in grade 6 (M=11.86 years old; SD = 0.56; 54% female; 81.5% Caucasian) and then annually through grade 12 regarding their individual symptoms of depression as well as the occurrence of MDEs. Individual symptoms of depression were assessed with the Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R) and depressive episodes were assessed with the Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation (LIFE). Results showed that within-person changes in sleep problems and low self-esteem/excessive guilt positively predicted an increased likelihood of an MDE for both boys and girls. Significant sex differences also were found. Within-person changes in anhedonia predicted an increased likelihood of a subsequent MDE among boys, whereas irritability predicted a decreased likelihood of a future MDE among boys, and concentration difficulties predicted a decreased likelihood of an MDE in girls. These results identified individual depressive symptoms that predicted subsequent depressive episodes in male and female adolescents, and may be used to guide the early detection, treatment, and prevention of depressive disorders in youth.

Keywords: adolescence, depressive symptoms, major depressive episode, sex differences

Depression affects approximately 14% of adolescents (Merikangas et al., 2010), and is associated with impaired academic and social functioning as well as increased risk for substance use and suicide (Birmaher, Ryan, Williamson, & Brent, 1996; Sihvola et al., 2007). Thus, depression in youth is a significant public health concern. One reliable predictor of a major depressive episode (MDE) in children and adolescents is prior subthreshold levels of depressive symptoms (e.g., Fergusson, Horwood, Ridder, & Beautrais, 2005; Johnson, Cohen, Kasen, 2004; Keenan et al., 2008; Shankman et al., 2009; Sihvola et al., 2007; see also Bertha & Balàz, 2013 for review). Less is known, however, about whether certain depressive symptoms are more likely than others to predict a later MDE; if so, then such symptoms could be used to identify targets for early intervention. Additionally, understanding the specific symptoms of depression that are most likely to predict an MDE may provide clues regarding the processes that underlie it (e.g., Fried, Nesse, Zivin, Guille, & Sen, 2014).

Studies of youth experiencing a current depressive episode have found that symptoms of sadness, sleep disturbance, appetite/weight changes, low self-esteem/guilt, and concentration problems were most prevalent, whereas suicidal ideation was the least common (Keenan et al., 2008; Roberts, Lewinsohn, & Seeley, 1995; Rohde, Beevers, Stice, & O’Neil, 2009). Additionally, using item response theory,Cole et al. (2011) found that sad mood and anhedonia were the most discriminating indicators of depression in youth. Thus, some symptoms have been found to be particularly likely to characterize youth already experiencing a current MDE, but less is known about which symptoms are most likely to temporally precede and predict a full MDE prior to its onset.

Studies of adults have identified some specific symptoms that reliably predict MDEs (e.g., Iacoviello, Alloy, Abramson, & Choi, 2010), and a few retrospective studies have examined the relation of depressive features during childhood to subsequent depressive diagnoses (e.g., Signoretta, Maremmani, Liguori, Perugi, & Akiskal, 2005; Soutullo et al., 2009). In a study of older adolescents experiencing their first depressive episode,Roberts et al. (1995) found that anhedonia and loss of energy uniquely predicted a second episode a year later. Pine, Cohen, Cohen, and Brook (1999) also showed that anhedonia and suicidal ideation predicted a diagnosis of depression 7 years later. Few such prospective studies exist in children, however, despite recent calls for examining prodromal states of disorders in youth (Leckman & Yazgan, 2010).

According to criteria defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), at least one of the core symptoms -- sadness, irritability (in children), anhedonia -- must be present for diagnosis of an MDE. In two different two-wave studies of adolescents, sad mood at the first assessment was found to increase the odds of meeting criteria for a subsequent MDE (Eaton, Badawi, & Melton, 1995; Georgiades, Lewinsohn, Monroe, & Seeley, 2006). Georgiades et al. (2006) showed that sadness uniquely predicted the onset of MDEs in adolescents when included in a model with other depressive symptoms. In one of the few longer-term prospective studies, Wolitzky-Taylor and colleagues (2014) found that endorsement of sad mood and/or anhedondia at the baseline assessment significantly predicted an MDE 7 to 9 years later.

The extent to which other depressive symptoms (e.g., sleep disturbance, appetite change, excessive guilt) predict an MDE over and above the core symptoms is less clear. Concentration problems (Haarasita, Marttunen, Kaprio, & Aro, 2001) and feelings of self-hatred (McKenzie et al., 2011) have been found to increase the likelihood of a later depressive episode among adolescents. Some theories of depression emphasize non-core symptoms as key contributors to the onset of a depressive disorder; for example, cognitive-vulnerability theories highlight low self-esteem and hopelessness as particularly important symptoms in the prediction of MDEs (e.g., Hankin & Abramson, 2001). Extending this earlier work, the present investigation aimed to identify which specific symptoms of depression predict a subsequent MDE using a longitudinal design that assessed depression across six years of adolescence.

A second goal of this study was to explore sex differences in the relations between specific symptoms and later MDEs. Rates of depression are about equal in boys and girls during childhood, but by about age 14, depression begins to increase at a faster rate for girls, and by late adolescence females are about twice as likely as males to be diagnosed with depression (e.g., Avenevoli, Swendsen, He, Burstein, & Merikangas, 2015; Hankin et al., 1998). Sex differences in the prevalence rates of specific symptoms of depression have been reported in adults (e.g., Khan, Gardner, Prescott, & Kendler, 2002; Smith et al., 2007), and youth (e.g., Baron & Campbell, 1993; Bennett, Ambrosini, Kudes, Metz, & Rabinovich, 2005). For example, in a sample of adolescents referred to an outpatient clinic, Bennett and colleagues (2005) found that depressed girls were more likely to have excessive guilt and increased appetite, whereas depressed boys had higher levels of anhedonia, depressed mood in the morning, and morning fatigue. Other studies of youth have reported higher levels of appetite/weight changes, fatigue, and sadness among females, and higher levels of irritability and sleep disturbance in males (e.g., Baron & Campbell, 1993). Other studies of children, however, have not found sex differences in the specific symptoms of depression (Georgiades et al., 2006; Kovacs, 2001).

A limitation of these previous investigations was their focus on already depressed youth; that is, sex differences in the rates of individual symptoms occurring during an MDE are not necessarily present prior to its onset. Nor do we know whether such symptoms differentially predict future depressive episodes in girls versus boys. In one of the few prospective studies to examine sex differences in the relation of individual symptoms to later depression, van Lang, Ferdinand, and Verhulst (2007) used a discriminate function analysis and found that sadness, appetite problems, feelings of worthlessness, and sleep problems discriminated between boys who did versus did not have a future depressive episode, whereas only sleep problems predicted a later MDE for girls.

In the present study, we used a multilevel modeling framework to examine which individual depressive symptoms predicted subsequent episodes of major depression, by considering within-person relations across adolescence. First, we examined the three core mood symptoms -- sadness, irritability, and anhedonia. Next, we tested the contribution of the remaining depressive symptoms, over and above the core symptoms; this included (a) four neurovegetative symptoms -- sleep disturbance, fatigue, appetite/weight changes, and psychomotor disturbances (i.e., agitation or retardation); and (b) three cognitive symptoms -- concentration difficulties/increased indecision, low self-esteem/excessive guilt, and suicidal ideation. Finally, we explored whether the predictive relation of these individual depressive symptoms to a subsequent MDE differed for boys and girls.

Method

Participants

Participants were 240 mothers and children who were first assessed in sixth grade (M = 11.86 years old; SD = 0.56; 54% female), and then annually through grade 12. The child sample was 81.5% Caucasian, 14.8% African American, and the remaining 3.7% were Hispanic, Native American, or reported “Other.” Families were predominantly working class (e.g., nurse’s aide, sales clerk) to middle class (e.g., store manager, teacher) with a mean socioeconomic status (Hollingshead, 1975) of 41.67 (SD = 13.29).

Procedure

The sample consisted of adolescents who were selected to vary in risk for depression as a function of their mother’s history of depressive disorders. Such a high-risk design provides greater variability in depressive symptoms and onsets of depressive episodes, thereby reducing potential problems associated with restriction of range often seen in normative samples of children (Kovacs, 1981). Parents of fifth grade children from metropolitan public schools were invited to participate in a study about parents and children. A brief health history questionnaire and a letter describing the project were sent to over 3,500 families. The primary inclusion criteria were that the family had a mother with a history of a mood disorder and the adolescent was in 6th grade. Of the 1,495 families interested in participating, the 587 mothers who had endorsed either a history of depression, use of antidepressants, or no history of psychopathology were interviewed further by telephone. Of these 587 screened, 349 mothers reported either a history of depression or no history of psychiatric problems. The remaining 238 families were excluded based on the following criteria: the mothers did not indicate sufficient symptoms to meet criteria for a depressive disorder (38%), the mothers had other psychiatric disorders that did not also include a depressive disorder (19%), they were no longer interested (21%), they or the target child had a serious medical condition (14%), the target child was in a different grade (6%), or the family had moved out of the area (2%).

The Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders diagnoses (SCID; Spitzer, Williams, Gibbon, & First, 1990) was administered in person to the 349 mothers who indicated a history of either some depression or no psychiatric problems. Of the 349 mothers interviewed, 109 were excluded because the mother indicated a history of a psychiatric disorder that did not also include a mood disorder or the mother or child had a serious medical condition. The final sample of 240 families consisted of 185 mothers with varying histories of a mood disorder (e.g., Major Depressive Disorder, Dysthymia) during the child’s life, and 55 mothers who were lifetime free of psychopathology. Of the 185 mothers with a history of a mood disorder, 72 had had a single episode and the remaining had had recurrent episodes (range = 2–7). Inter-rater reliability was calculated on a random 25% of these interviews, yielding 94% agreement (kappa=.88) for diagnoses of depressive disorders.

Children were first assessed in sixth grade (Time 1) and then yearly through 12th grade (Times 2 through 7). There was 19% attrition from Time 1 through 7. Research assistants, unaware of the mother’s psychiatric history, interviewed the mother and child separately in the family home. The analytic approach used in the current study accounted for missing data, such that all available data were used and participants with incomplete data were included in analyses. The study procedures met the approval of the institutional review board for the protection of human subjects. Mothers provided informed consent, and children signed an assent form. Measures relevant to the current study are described here.

Measures

Adolescents’ depressive symptoms

The Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R; Poznanski, Mokros, Grossman, & Freeman, 1987) is a semi-structured interview that assesses individual symptoms of depression experienced in the last two weeks. Mothers and adolescents were interviewed separately about the adolescents’ symptoms, by the same interviewer. The interviewer uses information obtained from both the mother and the adolescent to rate each symptom (Poznanski et al., 1995). The CDRS-R provides individual ratings for each symptom rated on a 7- or 5-point severity scale, and an overall summary score. In the current study, we used the items that assessed the 10 symptoms of depression: sad mood, anhedonia, irritability, sleep disturbance, fatigue, appetite/weight changes, psychomotor disturbance, concentration difficulties/increased indecision, low self-esteem/excessive guilt, and suicidal ideation. The CDRS has good internal consistency, construct validity, inter-rater reliability, and is sensitive to changes in specific symptoms over time (Jain et al., 2007; Mayes, Bernstein, Haley, Kennard, & Emslie, 2010). Cronbach’s alpha of the CDRS-R summary scores, based on audiotapes of the interviews, at each time point was ≥.72. Due to funding constraints, the CDRS-R was not administered in grade 10.

Diagnosis of depressive episodes

The Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation (LIFE; Keller et al., 1987), administered separately to adolescents and their mothers at each assessment, was used to assess the onset and offset of depressive episodes that occurred since the previous evaluation; all modules of the LIFE were administered. The same interviewer assessed the adolescent and mothers about the youths’ symptoms. Based on these interviews, youths were given a score of 1–6 on the Depression Symptom Rating (DSR) scale for each week of the follow-up interval. DSRs reflect the number of depressive symptoms endorsed and extent of impairment; scores of 5 or 6 for at least two consecutive weeks indicated an MDE. All interviews were audiotaped and a second rater reviewed a random 25% of interviews. Interrater reliability (kappa) for depression diagnoses was .81.

Maternal history of depression

To control for children’s risk for depression, maternal depression history was included as a covariate. Based on mothers’ baseline SCIDs, a chronicity/severity index was created, reflecting the number of diagnosed episodes a mother experienced in the target child’s life, the total amount of time during the child’s life that the mother had been depressed (summing the length of each episode), and the severity of each episode with regard to impairment, hospitalization, suicidality, and psychosis (see Horowitz & Garber, 2003). History of depression was coded as (1) mild = mother had no more than two depressive episodes, had been depressed for no more than 1 year, and had not experienced hospitalization, suicidality, or psychosis (n=49); (2) moderate = mother had 1–3 depressive episodes lasting 1–3 years of child’s life, or had one MDE of less than 1 year that included hospitalization, a suicide attempt, or psychotic features (n=84), or (3) severe = mother had been depressed for more than 4 years or had more than four depressive episodes during child’s life (n=52); mothers with no history of psychopathology (n=55) were coded as 0.

Data Analysis Plan

Hierarchical generalized linear models (HGLM) with a Bernouli distribution were run to predict a diagnosis of an MDE. Centering guidelines for examining within-person processes were followed (Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013); symptoms at Level 1 were person-centered, and the person-averages for these scores were included as predictors of the intercept at Level 2. This allowed us to examine within- and between-person relations between the individual depressive symptoms and a subsequent MDE.

To limit the number of predictors per model, we categorized symptoms conceptually and tested them as a group in the same model. Separate models tested the core, neurovegetative, and cognitive symptoms. Predictors included time, sex, risk (i.e., mother’s history of depression), individual symptoms of depression from the previous time point, and 2-way interactions between sex and previous symptoms. Analyses controlled for whether the adolescent had an MDE at any previous time at Level 1; one score was given at each assessment of 0 = no prior history, or 1 = prior MDE at any previous time point. Thus, models tested whether individual symptoms of depression predicted a subsequent MDE, over and above having had an earlier episode of an MDE. To test the contribution of the neurovegetative and cognitive symptoms on subsequent depressive episodes, we also controlled for the highest score of the three core mood symptoms endorsed for each participant in these models. This provided a conservative estimate of the unique contribution of the other symptoms for predicting an MDE, given that these symptoms may be correlated with the core symptoms.

Models were run using HLM 6.06 software (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). Parameter estimates were based on the population-average model with robust standard errors. Time was coded such that the intercept represented the likelihood of having an MDE between grades 11 and 12. Given that information about having a subsequent MDE was assessed six times (Times 2–7), only five parameters at Level 2 were allowed to be random effects; therefore the effect of time, having had a previous MDE, and the highest core symptom (in models testing the neurovegetative and cognitive symptoms) on a subsequent episode were modeled as fixed effects at Level 2, because these relations were not the focus of this study.

Results

Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations of symptom ratings on the CDRS-R across time, and the percentage of adolescents meeting criteria for an MDE (i.e., one-year prevalence rates). By the end of the study, 36 participants had had a single episode and 37 had had at least one recurrent episode (range = 2–7). The rate of depression diagnoses (new and recurrent) is slightly higher than those reported in community samples (e.g. Avenevoli et al., 2015; Hankin et al., 1998), likely reflecting the high-risk sample. All the individual depressive symptoms were significantly correlated with a subsequent MDE across time (average r =.22; full correlation table available upon request).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Individual Depressive Symptoms from the Children’s Depression Rating Scale – Revised (CDRS-R) and Depressive Diagnoses from the Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation (LIFE)

| Depressive Symptoms [M (SD)] | Grade 6 N = 240 |

Grade 7 N = 215 |

Grade 8 N = 206 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | ||

| Sad Mood | 1.95 (.79) | 1.78 (.89) | 1.86 (.89) | 1.87 (.99) | 1.91 (.84) | 1.66 (.75) | |

| Irritability | 2.11 (.83) | 2.11 (.86) | 2.21 (.80) | 2.35 (.99) | 2.20 (.87) | 2.32 (1.00) | |

| Anhedonia | 1.21 (.46) | 1.26 (.52) | 1.52 (.78) | 1.42 (.59) | 1.40 (.62) | 1.49 (.84) | |

| Sleep Disturbance | 1.36 (.69) | 1.39 (.73) | 1.55 (.92) | 1.44 (.75) | 1.56 (.84) | 1.52 (.77) | |

| Fatigue | 1.31 (.63) | 1.23 (.52) | 1.42 (.71) | 1.38 (.68) | 1.54 (.73) | 1.51 (.77) | |

| Appetite Problems/Weight change | 1.35 (.64) | 1.35 (.66) | 1.50 (.80) | 1.39 (.65) | 1.41 (.61) | 1.22 (.53) | |

| Psychomotor Disturbance | 1.17 (.50) | 1.15 (.45) | 1.08 (.37) | 1.05 (.22) | 1.04 (.23) | 1.15 (.45) | |

| Low Self-esteem/Guilt | 2.03 (.85) | 2.05 (.92) | 2.46 (.89) | 2.36 (.96) | 2.26 (.80) | 2.25 (.81) | |

| Concentration/Indecision | 1.27 (.69) | 1.20 (.50) | 1.38 (.77) | 1.68(1.09) | 1.34 (.65) | 1.58 (.94) | |

| Suicidal Ideation | 1.03 (.22) | 1.03 (.17) | 1.08 (.49) | 1.02 (.14) | 1.00 (.00) | 1.02 (.15) | |

| Depressive Symptoms [M (SD)] | Grade 9 N = 193 |

Grade 11 N = 187 |

Grade 12 N = 190 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | ||

| Sad Mood | 1.96 (.89) | 1.68 (.77) | 2.20(1.23) | 1.79(1.01) | 2.24 (1.34) | 1.77(1.09) | |

| Irritability | 2.30 (1.02) | 2.26 (.92) | 2.52(1.23) | 2.51(1.18) | 2.60 (1.32) | 2.23 (1.04) | |

| Anhedonia | 1.66 (.95) | 1.63 (.88) | 1.89(1.16) | 1.77(1.09) | 1.93(1.20) | 1.58 (1.01) | |

| Sleep Disturbance | 1.67 (.99) | 1.59 (.80) | 2.10(1.32) | 1.83(1.21) | 2.22 (1.36) | 1.71 (1.09) | |

| Fatigue | 1.91 (.93) | 1.69 (.90) | 2.49(1.12) | 2.32(1.08) | 2.58 (1.23) | 2.05 (.94) | |

| Appetite Problems/Weight change | 1.55 (.80) | 1.34 (.68) | 1.59(.97) | 1.50 (.86) | 1.73 (1.10) | 1.42 (.83) | |

| Psychomotor Disturbance | 1.14 (.58) | 1.08 (.31) | 1.29 (.61) | 1.25 (.56) | 1.35 (.91) | 1.23 (.60) | |

| Low Self-esteem/Guilt | 2.47 (.90) | 2.20 (.71) | 2.74(.97) | 2.37(.97) | 2.91 (1.20) | 2.24 (1.01) | |

| Concentration/Indecision | 1.48 (.82) | 1.67 (.92) | 1.72(1.07) | 1.71(1.03) | 1.68 (1.10) | 1.59(1.03) | |

| Suicidal Ideation | 1.10 (.41) | 1.09 (.39) | 1.18 (.63) | 1.05 (.31) | 1.07 (.37) | 1.04 (.34) | |

| Major Depressive Episode Diagnosesa | Grade 6b | Grade 7 | Grade 8 | Grade 9 | Grade 10 | Grade 11 | Grade 12 |

| Female | 3.8% | 8.0% | 4.1% | 8.3% | 16.4% | 11.8% | 23.6% |

| Male | 1.8% | 1.0% | 1.9% | 3.1% | 11.8% | 9.7% | 20.2% |

Note. Individual symptoms assessed using the CDRS-R; the CDRS-R was not administered in grade 10.

Percentage meeting criteria for an MDE since the previous assessment based on information from K-LIFE interview; may include a recurrent episode.

Percentage of diagnoses at grade 6 represents participants with an MDE prior to study entry.

Preliminary Analyses

HGLM models were first run to determine the likelihood of having an MDE across adolescence, controlling for sex, risk, and an MDE at any previous time in the adolescent’s life. The odds of having an MDE between grades 11 and 12 for the average adolescent in this sample (with regard to sex and risk) without a previous MDE was .31 (95% Confidence Interval [CI] [.24, .41]; b = −1.17, p<.001), indicating that, on average, the probability of having an MDE between 11th and 12th grade was 23.7%. Having a previous MDE significantly increased the likelihood of a subsequent MDE, b = 1.17, p<.001, Odds Ratio [OR] = 3.21, 95% CI [1.85, 5.55].

Sex and risk did not moderate the relation between a previous and future MDE. The odds of having an MDE between Grades 11 and 12 also were positively related to risk, b = .57, p<.001, OR = 1.77, 95% CI [1.42, 2.20]. Finally, the likelihood of having an MDE between grades 7 and 12 increased each year, b = .31, p<.001, OR = 1.36, 95% CI [1.29, 1.44], and increased at a faster rate for boys, b = .39, p<.001, OR = 1.48, 95% CI [1.36, 1.60], as compared to girls, b = .24, p<.001, OR = 1.27, 95% CI [1.17,1.38]; however, girls had a higher likelihood of an MDE than boys throughout the study period. Based on these preliminary results, further analyses controlled for the main effect of risk and the time×sex interaction.

Core Symptoms of a Depressive Episode

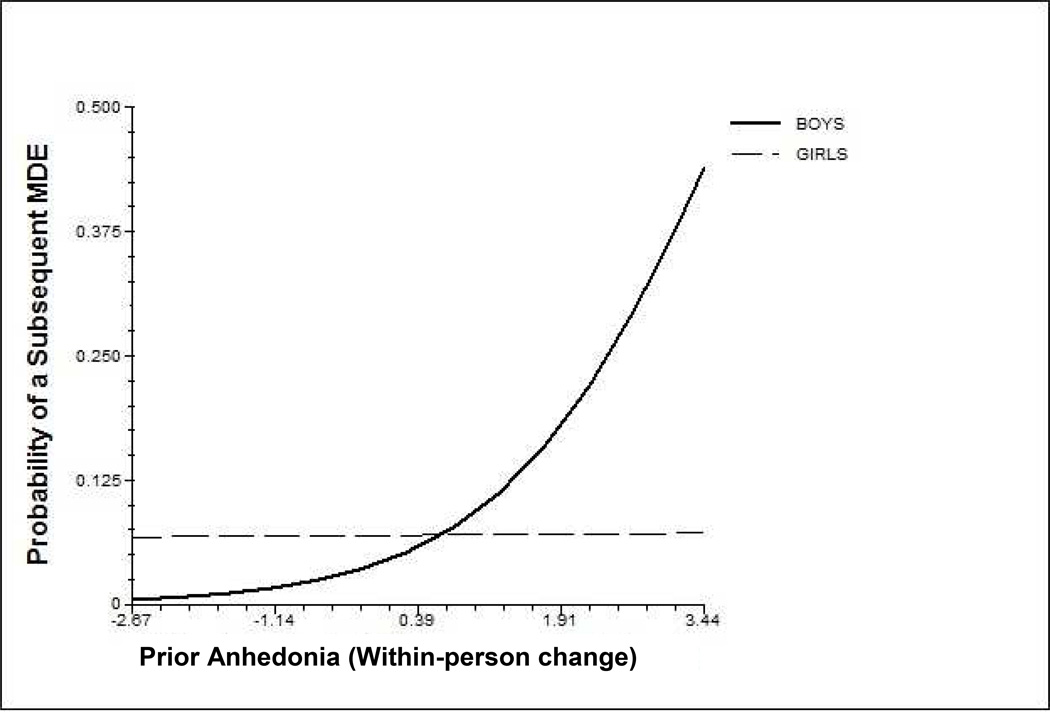

Results examining the three core depressive symptoms are presented in Table 2. With regard to within-person relations, significant sex differences were found for anhedonia and irritability in predicting an MDE. Anhedonia was a significant predictor of a subsequent MDE for boys (Figure 1). That is, a one-unit increase from boys’ average level of anhedonia increased the odds of having an MDE in the next year by 2.30, b = .83, p<.001, OR = 2.30, 95% CI [1.63, 3.26]; anhedonia did not significantly predict a subsequent MDE in girls (b = .01, p = .95). Irritability also was related to boys’ risk for MDE such that within-person decreases in irritability predicted a greater likelihood of having a subsequent MDE, b = -.33, p = .03, OR = .72, 95% CI [.53, .97]. Significant between-person relations were found indicating that higher average levels of each of the three core symptoms uniquely predicted an increased likelihood of an MDE between grades 11 and 12.

Table 2.

Results from HGLM Analyses Predicting the Likelihood of a Subsequent Depressive Episode: Core Mood Symptoms

| Major Depressive Episode |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | t-ratio | OR | 95 % CI for OR | |

| Intercept | −1.38 | .17 | 8.00** | .25 | [0.18, 0.35] |

| Sexa | −.26 | .34 | 0.76 | .77 | [0.39, 1.52] |

| Riskb | .34 | .08 | 4.28** | 1.41 | [1.20, 1.64] |

| Person-average Sad Mood (Between) | .66 | .18 | 3.70** | 1.93 | [1.36, 2.73] |

| Person-average Anhedonia (Between) | .60 | .22 | 2.69** | 1.82 | [1.17, 2.82] |

| Person-average Irritability (Between) | .38 | .14 | 2.76** | 1.47 | [1.12, 1.93] |

| Timecd | .36 | .04 | 8.15** | 1.44 | [1.32, 1.57] |

| Time × Sex | −.21 | .09 | 2.40** | .81 | [0.69, 0.96] |

| Previous Depressive Episodec,e | .52 | .31 | 1.68† | 1.69 | [0.92, 3.10] |

| Sad Mood (Within) | −.03 | .11 | 0.30 | .97 | [0.77, 1.21] |

| Sad Mood × Sex | .35 | .23 | 1.57 | 1.43 | [0.91, 2.22] |

| Anhedonia (Within) | .39 | .12 | 3.29** | 1.47 | [1.17, 1.86] |

| Anhedonia × Sex | −.83 | .24 | 3.46** | .44 | [0.27, 0.70] |

| Irritability (Within) | −.02 | .11 | .22 | .98 | [0.79, 1.21] |

| Irritability × Sex | .57 | .22 | 2.63** | 1.76 | [1.15, 2.70] |

Note. Three core symptoms tested together in the same model. Results from population-average model with robust standard errors presented.

Sex coded: −0.5 = boy, 0.5 = girl.

Risk = maternal depression history coded as 0 = no history of depression, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, and 3 = severe; (Risk variable grand-mean centered).

Parameter fixed at Level 2.

Time was coded as grade 12 = 0.

grand mean centered at Level 1.

p< .10;

p< .05;

p< .01.

Figure 1.

Within-person changes in anhedonia as a predictor of the probability of a subsequent Major Depressive Episode (MDE) within the next year for girls and boys.

Neurovegetative Symptoms

Next, we examined the four neurovegetative symptoms in the same model, as predictors of a subsequent MDE (Table 3). To assess the unique contribution of these symptoms over and above the core symptoms , these models controlled for within-person changes and between-person differences in the highest score of the three core symptoms (i.e., sad mood, irritability, or anhedonia) endorsed for each participant. Within-person changes in sleep disturbance significantly predicted an increased likelihood of a subsequent MDE, b = .34, p<.001, OR = 1.41, 95% CI [1.18, 1.67]. With regard to between-person relations, youths who, on average, had higher levels of sleep disturbances and appetite/weight changes compared to their peers had a greater likelihood of having an MDE between grades 11 and 12.

Table 3.

Results from HGLM Analyses Predicting the Likelihood of a Subsequent Depressive Episode: Neurovegetative Symptoms

| Major Depressive Episode |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | t-ratio | OR | 95% CI for OR | |

| Intercept | −1.45 | .16 | 8.94** | .23 | [0.17, 0.32] |

| Sexa | −.06 | .33 | .19 | .94 | [0.49, 1.81] |

| Riskb | .21 | .06 | 3.44** | 1.24 | [1.10, 1.40] |

| Person-average Sleep (Between) | .29 | .13 | 2.30** | 1.34 | [1.04, 1.72] |

| Person-average Fatigue (Between) | .19 | .16 | 1.23 | 1.21 | [0.89, 1.65] |

| Person-average Appetite/Weight (Between) | .58 | .17 | 3.35** | 1.78 | [1.27, 2.51] |

| Person-average Psychomotor (Between) | .53 | .28 | 1.85† | 1.69 | [0.97, 2.97] |

| Timecd | .29 | .04 | 7.12** | 1.34 | [1.24, 1.46] |

| Time × Sex | −.08 | .08 | 1.07 | .92 | [0.78, 1.07] |

| Previous Depressive Episodec,e | .59 | .25 | 2.39* | 1.81 | [1.11, 2.95] |

| Highest Core Symptome | −.01 | .09 | .09 | .99 | [0.83, 1.19] |

| Sleep (Within) | .34 | .09 | 3.88* | 1.41 | [1.18, 1.67] |

| Sleep × Sex | −.25 | .18 | 1.40 | .78 | [0.54, 1.11] |

| Fatigue (Within) | −.02 | .09 | .24 | .98 | [0.81, 1.19] |

| Fatigue × Sex | −.27 | .18 | 1.53 | .76 | [0.53, 1.08] |

| Appetite/Weight (Within) | .07 | .11 | .64 | 1.07 | [0.87, 1.33] |

| Appetite/Weight × Sex | .05 | .22 | .24 | 1.06 | [0.68, 1.63] |

| Psychomotor (Within) | −.17 | .17 | 1.00 | .85 | [0.61, 1.18] |

| Psychomotor × Sex | .35 | .35 | 1.00 | 1.42 | [0.71, 2.81] |

Note. Four neurovegetative symptoms tested together in the same model. Results from population-average model with robust standard errors presented.

Sex coded: −0.5 = boy, 0.5 = girl.

Risk = maternal depression history coded as 0 = no history of depression, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, and 3 = severe; (Risk variable grand-mean centered).

Parameter was fixed at Level 2.

Time was coded as grade 12 = 0.

grand-mean centered at Level 1.

p< .10;

p< .05;

p< .01

Cognitive Symptoms

The three cognitive symptoms were tested simultaneously as predictors of a subsequent MDE (Table 4). Within-person increases in worthlessness/guilt significantly predicted a greater likelihood of a subsequent MDE, b = .33, p = .007, OR = 1.40, 95% CI [1.10, 1.78]. There was a significant sex difference in the relation between within-person changes in concentration difficulties and a subsequent MDE, b = −.54, p = .014. For girls, within-person increases in levels of concentration difficulties predicted a lower likelihood of an MDE (OR = .61, p<.001), whereas for boys within-person changes in levels of concentration problems did not predict an MDE (OR = 1.05, p = .81). Between-person relations indicated that adolescents with worse self-esteem/ guilt, and more concentration/decision-making problems than their peers had a higher likelihood of having an MDE between grades 11 and 12.

Table 4.

Results from HGLM Analyses Predicting the Likelihood of a Subsequent Depressive Episode: Cognitive Symptoms

| Major Depressive Episode |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | t-ratio | OR | 95% CI for OR | |

| Intercept | −1.51 | .17 | 8.62** | .22 | [0.16, 0.31] |

| Sexa | −.24 | .36 | .68 | .79 | [0.39, 1.58] |

| Riskb | .25 | .08 | 3.28** | 1.29 | [1.11, 1.50] |

| Person-average Concentration (Between) | .47 | .16 | 2.86** | 1.60 | [1.16, 2.20] |

| Person-average Self-esteem/Guilt (Between) | .61 | .15 | 4.13** | 1.84 | [1.38, 2.47] |

| Person-average Suicide Ideation (Between) | −.14 | .37 | .37 | .88 | [0.42, 1.81] |

| Timecd | .33 | .04 | 7.56** | 1.39 | [1.27, 1.51] |

| Time × Sex | −.19 | .08 | 2.31* | .83 | [0.70, 0.97] |

| Previous Depressive Episodec,e | .68 | .28 | 2.47* | 1.98 | [1.15, 3.41] |

| Highest Core Symptome | .16 | .12 | 1.33** | 1.18 | [0.93, 1.50] |

| Concentration (Within) | −.25 | .11 | 2.25** | .78 | [0.63, 0.97] |

| Concentration × Sex | −.54 | .22 | 2.47* | .58 | [0.38, 0.90] |

| Low Self-esteem/Guilt (Within) | .34 | .12 | 2.75** | 1.40 | [1.10, 1.78] |

| Low Self-esteem/Guilt × Sex | −.06 | .22 | .29 | .94 | [0.62, 1.44] |

| Suicide Ideation (Within) | .15 | .32 | .46 | 1.16 | [0.61, 2.17] |

| Suicide Ideation × Sex | .09 | .67 | .13 | 1.09 | [0.29, 4.07] |

Note. Three cognitive symptoms tested together in the same model. Results from population-average model with robust standard errors presented.

Sex was coded: −0.5 = boy, 0.5 = girl.

Risk = maternal depression history coded as 0 = no history of depression, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, and 3 = severe; (Risk variable grand-mean centered).

Parameter was fixed at Level 2.

Time was coded such that grade 12 = 0.

grand-mean centered at Level 1.

p< .05;

p< .01.

Discussion

The current prospective study identified within-person changes in individual symptoms of depressive disorder that predicted a subsequent MDE during adolescence. Several notable findings of this study advance prior work in this area. First, whereas previous research examined prevalence rates and sex differences in individual symptoms of youth who were in a current depressive episode, the present prospective study identified which symptoms temporally preceded and predicted subsequent episodes. Second, extending previous work on between-person relations, the current study examined the extent to which within-person changes in levels of individual symptoms increased risk for a subsequent MDE. Third, this study provided a more conservative estimate of the contribution of specific depressive symptoms to the prediction of an MDE, over and above the known risk factors of prior depression and maternal depression history. Fourth, relations between symptoms and a subsequent MDE were assessed over 6 years across adolescence, when rates of depression are rising (e.g., Avenevoli et al., 2015). Thus, the findings may be important for early detection of targets for intervention. Although it is possible that early symptoms that precede an MDE may not be the most impairing, some evidence exists that prodromal symptoms represent the primary symptoms during the episode and are the last to remit (Iacoviello et al., 2010).

According to DSM-5, at least one of the core symptoms (i.e., sadness, irritability, or anhedonia) is required for an MDE diagnosis. The present study found that these individual core symptoms did not significantly predict future MDEs for girls, whereas anhedonia predicted MDEs for boys, such that within-person increases in anhedonia (i.e., increases from the individual’s typical level) significantly predicted a future MDE. Other studies have shown that anhedonia is more common in depressed boys than girls (e.g., Bennett et al., 2005), and normatively, feelings of boredom and disinterest are more common among adolescent boys than girls (e.g., Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2010; Gordon & Caltabiano, 1996). An escalation of these symptoms into more persistent and debilitating loss of interest or pleasure may signal a need for early intervention, particularly given evidence that anhedonia is associated with delayed recovery from depression in treatment-resistant adolescents (McMakin et al., 2012). The prediction of an MDE from anhedonia is consistent with the tripartite model of anxiety and depression such that anhedonia (low positive affect) predicted depression, whereas the core symptoms that indicate high negative affect (i.e., sadness, irritability) have not been found to be unique to depression (e.g., Chorpita, Plummer, & Moffitt, 2000; Lonigan, Carey, & Finch, 1994). Clinical interventions that emphasize behavioral activation and increasing pleasurable activities (e.g., Dimidjian et al., 2006) may be particularly appropriate for boys exhibiting increases in anhedonia during adolescence.

Beyond the core depressive symptoms, sleep disturbance and low self-esteem/ excessive guilt predicted an increased likelihood of having a subsequent MDE in both girls and boys. Studies with adults have consistently identified sleep problems as a robust predictor of relapse and recurrence in depression (Buysse et al., 1996; Dombrovski et al., 2008; Kupfer, Frank, McEachran, & Grochocinski, 1990; Whitcomb-Smith et al., 2014). Although fewer studies have been conducted with youth, sleep problems in children and adolescents also have been found to be associated with increased depressive symptoms (e.g., Alfano, Zakem, Costa, Taylor, & Weems, 2009; Ford & Cooper-Patrick, 2001; Gregory, Rijsdijk, Lau, Dalh, & Eley, 2009; see also Dahl & Harvey, 2007 and Shochat, Cohen-Zion, & Tzischinsky, 2014 for reviews). For example, Gregory et al. (2009) showed that sleep problems at age 8 were predictive of depression at age 10. Alfano et al. (2009) reported that depressive symptoms and sleep problems were more strongly associated in adolescents (ages 12–17), than in children (ages 6–11). Dombrovski and colleagues (2008) argued that sleep problems may be a biological marker of risk for depression, characterized by hyper-arousal that interferes with both sleep and mood regulation. Clarke and Harvey (2012) proposed that treating sleep problems and depression concurrently will provide better treatment outcomes for youth than traditional treatments of depression alone. The present results also are consistent with findings from a cross-sectional study showing lower self-esteem and excessive guilt in depressed as compared to non-depressed youth (e.g., Keenan et al. 2008), and with a two-wave longitudinal study showing that thoughts of worthlessness predicted an MDE one year later in boys (van Lang et al., 2007).

Of note, the current study demonstrated that relations between depressive symptoms and a subsequent MDE differed when considering within-person versus between-person relations. Most research in this area has focused on identifying symptoms that characterize individuals at higher risk for depression and that predict MDE onset compared to their peers (between-person relations). Consistent with these previous studies, the present findings suggest that, on average, youth who exhibit relatively enduring elevations on specific depressive symptoms across adolescence are at increased risk for an MDE by the end of high school. However, translating between-person results into improved early detection of at-risk youth is difficult because these analyses are based on adolescents’ rank order relative to their peers, not relative to their own typical functioning. That is, knowing that an adolescent has lower self-esteem compared to his or her peers, in and of itself, may not mean that a future MDE is likely. Rather, controlling for these between-person differences, the current findings underscore the importance of examining changes (i.e., worsening) of specific symptoms, from one’s typical level, for predicting an increased risk of a future MDE.

Importantly, the approach of examining within-in person relations is directly aligned with both theoretical perspectives and clinical assessment of depression; that is, to meet criteria for a particular symptom, there must be evidence of a change or worsening relative to ones’ typical level of functioning—not relative to others. Moreover, examining within-person changes in depressive symptoms allows us to distinguish between personal traits and prodromal symptoms, which likely require different treatment approaches (Kovacs & Lopez-Duran, 2010). Therefore, within-person results may be of great value to parents, teachers, and clinicians who can use observations of changes in a youth’s behavior (compared to the youth’s typical behaviors) to inform decisions regarding the need for intervention.

Some unexpected findings emerged as well, and thus require replication. Lower likelihood of having an MDE was linked to within-person increases in irritability in boys, and within-person increases in concentration problems in girls. One possible explanation is that the behavioral and psychosocial impairment associated with irritability and concentration problems signal to parents or teachers the need to intervene, which, in turn, could reduce the likelihood of a future MDE. Irritability more commonly accompanies depressed mood in boys than girls (Stringaris, Maughan, Copeland, Costello, & Angold, 2013), and externalizing problems are a stronger predictor of internalizing trajectories in boys (Letcher, Smart, Sanson, & Toumbourou, 2008). Given that both parents and teachers tend to more accurately identify children at-risk for externalizing than internalizing disorders (Dwyer, Nicholson, & Battistutta, 2006), worsening irritability in boys may signal an increase in externalizing symptoms and the need for intervention. Our finding, however, is counter to what has been found in studies of betweenperson relations. For example, cross-sectional studies have shown irritability to be associated with an increased risk of depression (e.g., Stingaris, Cohen, Pine, & Leibenluft, 2009). A recent longitudinal study reported that childhood irritability predicted higher levels of depressive symptoms in adolescence (Whelan, Leibenluft, Stringaris, & Barker, in press). Irritability is an especially important symptom warranting further study, as it is transdiagnostic and characteristic of several other disorders (e.g., bipolar disorder, dysregulated mood disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder) as well as depression (Stringaris, 2011).

Second, concentration problems can have a negative impact on school performance, (Sijtsema, Verboom, Pennix, Verhulst, & Ormel, 2014), which could prompt teachers to alert parents to potential prodromal depressive symptoms and the need for intervention. The current study, however, did not have information about children’s treatment, and therefore, we were not able to examine this post hoc explanation. Moreover, whereas poor school performance can be indicative of depressive symptoms, it also is a warning sign of a wide range of other potential problems (e.g., attention deficit disorder, anxiety disorder) in youth.

Limitations of the present study provide directions for future research. First, the measure of adolescents’’ individual depressive symptoms obtained at each annual assessment (CDRSR), evaluated their symptoms occurring during the past two weeks, which is a relatively narrow time frame. Nevertheless, the findings highlight that even brief snapshots of depressive symptoms provided predictive utility regarding the occurrence of depressive episodes in adolescents, over and above any prior MDEs. A strength of the current study was that we followed adolescents over a 6-year period, which provided more robust estimates of longitudinal relations between individual symptoms of depression and subsequent MDEs; this is in contrast to most previous studies that have assessed adolescents only twice (e.g., Georgiades et al., 2006; McKenzie et al., 2011; van Lang et al., 2007).

Second, the longitudinal design allowed us to examine the temporal relations between individual depressive symptoms and subsequent MDEs. Nevertheless, the data were still correlational. Some other, unmeasured variables could have accounted for the prospective relation between specific depressive symptoms and subsequent episodes (e.g., genes, stress).

Third, we over-sampled offspring of mothers with histories of depression in order to obtain variability on the depression measures and to identify predictors of depression among youth at risk; the results may not generalize to a purely community sample, however. Fourth, a strength of the analyses is that all models controlled for the severity of mothers’ depression history; however, we were unable to track the time-varying nature of mothers’ depression over the course of the study in the models.

Finally, the pathways by which individual symptoms of depression confer risk for MDE were not addressed. One hypothesis is that symptoms of depression (e.g., dysphoric mood, anhedonia) lead to cognitive, family, and social problems, which in turn may generate or exacerbate stress and precipitate a full depressive episode (Hammen & Rudolph, 1996). Further explication of the intervening mechanisms (e.g., neurobiological, psychosocial) is needed to develop interventions that forestall the progression of individual symptoms into full disorders. Moreover, symptoms that predict adolescent- versus adult-onset depression may differ; understanding these developmental differences may shed light on whether there are unique etiological and maintenance pathways for early- versus later-onset depression.

In conclusion, results of this study have clinical implications regarding whom and what to target for intervention. We identified specific symptoms that, when worsened, predicted future depressive episodes in adolescents. For boys, anhedonia was especially noteworthy; in both boys and girls, sleep disturbances and low self-esteem/excessive guilt predicted future MDEs These findings are consistent with Cole et al. (2011), who also noted that worthlessness/guilt and sleep disturbances may represent early warning signs for depression. Thus, clinicians, parents, and teachers should be especially vigilant regarding changes in these symptoms so that at-risk youth can be provided with early interventions aimed at preventing escalation into a full depressive disorder.

Recent meta-analyses of depression prevention programs have shown that larger effect sizes were found in studies with targeted high-risk groups (Merry et al., 2011; Sandler et al., 2014). Thus, ensuring that programs are targeting those most at-risk appears to be key to preventing depression. In previous work, high-risk often has been defined as having a parent with depression, current elevated depressive symptoms, or both. The present study suggests that an additional consideration in determining risk for depression, and possibly increasing efficacy of prevention programs, may be to target sex-specific, within-individual changes in the particular depressive symptoms observed here.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Chrystyna D. Kouros, Dept. of Psychology, Southern Methodist University

Matthew C. Morris, Dept. of Family and Community Medicine, Meharry Medical College

Judy Garber, Department of Psychology and Human Development, Vanderbilt University.

References

- Alfano CA, Zakem AH, Costa NM, Taylor LK, Weems CF. Sleep problems and their relation to cognitive factors, anxiety, and depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26:503–512. doi: 10.1002/da.20443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: APA; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Avenevoli S, Swendsen J, He J-P, Burstein M, Merikangas KR. Major depression in the National Comorbidity Survey- Adolescent Supplement: Prevalence, correlates, and treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2015;54:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron P, Campbell TL. Gender differences in the expression of depressive symptoms in middle adolescents: An extension of earlier findings. Adolescence. 1993;28:903–911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DS, Ambrosini PJ, Kudes D, Metz C, Rabinovich H. Gender differences in adolescent depression: Do symptoms differ for boys and girls? Journal of Affective Disorders. 2005;89:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertha EA, Balàz J. Subthreshold depression in adolescence: A systematic review. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;22:589–603. doi: 10.1007/s00787-013-0411-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Ryan ND, Williamson DE, Brent DA. Childhood and adolescent depression: A review of the past 10 year, Part I. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:1575–1583. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199612000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Laurenceau J-P. Intensive longitudinal methods: An introduction to diary and experience sampling methods. New York: Guildford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Hoch CC, Houck PR, Kupfer DJ, Mazumdar S, Frank E. Longitudinal effects of nortriptyline on EEG sleep and the likelihood of recurrence in elderly depressed patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14:243–252. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(95)00114-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Plummer CM, Moffitt CE. Relations of tripartite dimensions of emotion to childhood anxiety and mood disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000;28:299–310. doi: 10.1023/a:1005152505888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke G, Harvey AG. The complex role of sleep in adolescent depression. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2012;21:385–400. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Cai L, Martin NC, Findling RL, Youngstrom EA, Garber J, Forehand R. Psychological Assessment. 2011;23:819–833. doi: 10.1037/a0023518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl RE, Harvey AG. Sleep in children and adolescents with behavioral and emotional disorders. Sleep Medicine Clinics. 2007;2:501–511. [Google Scholar]

- Dimidjian S, Hollon SD, Dobson KS, Schmaling KB, Kohlenberg RJ, Addis M, Jacobson NS. Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of adults with major depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:658–670. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombrovski AY, Cyranowski JM, Mulsant BH, Houck PR, Buysse DJ, Andreescu C, Frank E. Which symptoms predict recurrence of depression in women treated with maintenance interpersonal psychotherapy? Depression and anxiety. 2008;12:1060–1066. doi: 10.1002/da.20467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer SB, Nicholson JM, Battistutta D. Parent and teacher identification of children at risk of developing internalizing and externalizing mental health problems: A comparison of screening methods. Prevention Science. 2006;7:343–357. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton WW, Badawi M, Melton B. Prodromes and precursors: Epidemiologic data for primary prevention of disorders with slow onset. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:967–971. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM, Beautrais AL. Subthreshold depression in adolescence and mental health outcomes in adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:66–72. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca-Pedrero E, Wells C, Paino M, Lemos-Giráldez S, Villazón-García Ú, Sierra S, González MPG, Bobes J, Muñiz J. Measurement invariance of the Reynolds Depression Adolescent Scale across gender and age. International Journal of Testing. 2010;10:133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Ford DE, Cooper-Patrick L. Sleep disturbances and mood disorders: An epidemiological perspective. Depression and Anxiety. 2001;14:3–6. doi: 10.1002/da.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried EI, Nesse RM, Zivin K, Guille C, Sen S. Depression is more than the sum score of its parts: Individual DSM symptoms have different risk factors. Psychological Medicine. 2014;44:2067–2076. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiades K, Lewinsohn PM, Monroe SM, Seeley JR. Major depressive disorder in adolescence: The role of subthreshold symptoms. Journal of the American Academy for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:936–944. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000223313.25536.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon WR, Caltabiano ML. Urban-rural differences in adolescent self-esteem, leisure boredom, and sensation seeking as predictors of leisure-time usage and satisfaction. Adolescence. 1996;31:883–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory AM, Rijsdijk FV, Lau JY, Dahl RE, Eley TC. The direction of longitudinal associations between sleep problems and depression symptoms: A study of twins aged 8 and 10 years. Sleep. 2008;32:189–199. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.2.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haarasilta L, Marttunen M, Kaprio J, Aro H. The 12-month prevalence and characteristics of major depressive episode in a representative sample of adolescents and young adults. Psychological Medicine. 2001;31:1169–1179. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Rudolph KD. Childhood depression. In: Mash EJ, Barkley RA, editors. Child Psychopathology. New York, New York: Guildford Press; 1996. pp. 153–195. [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY. Development of gender differences in depression: An elaborated cognitive vulnerability-transactional stress theory. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:773–796. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, Angell KE. Development of depression from preschool to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:128–140. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four factor index of social status. New Haven, CT: Yale University; 1975. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz JL, Garber J. Relation of intelligence and religiosity to depressive disorders in offspring of depressed and nondepressed mothers. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42:578–586. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046831.09750.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacoviello BM, Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Choi JY. The early course of depression: A longitudinal investigation of prodromal symptoms and their relation to the symptomatic course of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:459–467. doi: 10.1037/a0020114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S, Carmody TJ, Trivedi MH, Hughes C, Bernstein, Morris DW, Rush AJ. A psychometric evaluation of the CDRS and MADRS in assessing depressive symptoms in children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:1204–1212. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3180cc2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Kasen S. Minor depression during adolescence and mental health outcomes during adulthood. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;195:264–265. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.054239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K, Hipwell AE, Feng X, Babinski D, Hinze A, Rischall M, Hennenberger A. Subthreshold symptoms of depression in preadolescent girls are stable and predictive of depressive disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:1433–1442. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181886eab. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, Nielson E, Endicott J, Andreasen NC. The Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation: A comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1987;44:540–548. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180050009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan AA, Gardner CO, Prescott CA, Kendler KS. Gender differences in the symptoms of major depression in opposite-sex dizygotic twin pairs. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1427–1429. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Rating scales to assess depression in school-aged children. Acta Paedopsychiatrica: International Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1981;46:305–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Gender and the course of major depressive disorder through adolescence in clinical referred youngsters. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:1079–1085. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200109000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M, Lopez-Duran N. Prodromal symptoms and atypical affectivity as predictors of major depression in juveniles: Implications for prevention. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;4:472–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02230.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupfer DJ, Frank E, McEachran AB, Grochocinski VJ. Delta sleep ratio: A biological correlate of early recurrence in unipolar affective disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1990;47:1100–1105. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810240020004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leckman JF, Yazgan MY. Editorial: Developmental transitions to psychopathology: From genomics and epigenomics to social policy. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51:333–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letcher P, Smart D, Sanson A, Toumbourou JW. Psychosocial precursors and correlates of differing internalizing trajectories from 3 to 15 years. Social Development. 2008;18:618–646. [Google Scholar]

- Lonigan CJ, Carey MP, Finch AJ. Anxiety and depression in children and adolescents: Negative affectivity and the utility of self-reports. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:1000–1008. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.5.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayes TL, Bernstein IH, Haley CL, Kennard BD, Emslie J. Psychometric properties of the Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised in Adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2010;20:513–516. doi: 10.1089/cap.2010.0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie DP, Toumbourou JW, Forbes AB, Mackinnon AJ, McMorris BJ, Catalano RF, Patton GC. Predicting future depression in adolescents using the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire: A two-nation study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;134:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMakin DL, Olino TM, Porta G, Dietz LJ, Emslie G, Clarke G, Wagner KD, Asarnoq JR, Ryan ND, Birmaher B, Shamseddeen W, Mayes T, Kennard B, Spirito A, Keller M, Lynch FL, Dickerson JF, Brent DA. Anhedonia predicts poorer recovery among youth with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment-resistant depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51:404–411. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas DR, He J, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Swendsen J. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Study-Adolescent Supplement. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine DS, Cohen E, Cohen P, Brooks J. Adolescent depressive symptoms as predictors of adult depression: Moodiness or mood disorder? American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:133–135. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poznanski E, Mokros HB, Grossman J, Freeman LN. Diagnostic criteria in childhood depression. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1985;142:1168–1173. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.10.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Symptoms of DSM-III-R major depression in adolescence: Evidence from an epidemiological survey. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:1608–1617. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199512000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Beevers CG, Stice E, O’Neil K. Major and minor depression in female adolescents: Onset, course, symptom presentation, and demographic associations. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65:1339–1349. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler R, Wolchik SA, Cruden G, Mahrer NE, Ahn S, Brincks A, Brown CH. Overview of meta-analyses of the prevention of mental health, substance use, and conduct problems. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2014;10:25.1–25.31. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankman SA, Lewinsohn PM, Klein DN, Small JW, Seeley JR, Altman SE. Subthreshold conditions as precursors for full syndrome disorders: A 15-year longitudinal study of multiple diagnostic classes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:1485–1494. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02117.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sihvola E, Keski-Rahkonen A, Dick DM, Pulkkinen L, Rose RJ, Marttunen M, Kaprio J. Minor depression in adolescence: Phenomenology and clinical correlates. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;97:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shochat T, Cohen-Zion M, Tzischinsky O. Functional consequences of inadequate sleep in adolescents: A systematic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2014;18:75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Signoretta S, Maremmani I, Liguori A, Perugi G, Akiskal HS. Affective temperament traits measured by TEMPS-I and emotional-behavioral problems in clinically-well children, adolescents, and young adults. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2005;85:169–180. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00100-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sijtsema JJ, Verboom CE, Pennix BWJH, Verhulst FC, Ormel J. Psychopathology and academic performance, social well-being, and social preference at school: The TRAILS study. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2014;45:273–284. doi: 10.1007/s10578-013-0399-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DJ, Kyle S, Forty L, Cooper C, Walters J, Russell E, Craddock N. Differences in depressive symptom profile between males and females. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;108:279–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soutullo CA, Escamilla-Canales I, Wozniak J, Gamazo-Garran P, Figueroa-Quintana A, Biederman J. Pediatric bipolar disorder in a Spanish sample: Features before and at the time of diagnosis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;118:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID): History, rationale, and description. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1990;49:624–629. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A. Irritability in children and adolescents: A challenge for DSM-5. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;20:61–66. doi: 10.1007/s00787-010-0150-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Cohen P, Pine DS, Leibenluft E. Adult outcomes of youth irritability: A 20-year prospective community-based study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:1048–1054. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Maughan B, Copeland WS, Costello EJ, Angold A. Irritable mood as a symptom of depression in youth: Prevalence, developmental, and clinical correlates in the Great Smoky Mountains Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52:831–840. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan YM, Leibenluft E, Stringaris A, Barker ED. Pathways from maternal depressive symptoms to adolescent depressive symptoms: The unique contribution of irritability symptoms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12395. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitcomb-Smith S, Sigmon ST, Martison A, Young M, Craner J, Boulard N. The temporal development of mood, cognitive, and vegetative symptoms in recurrent SAD episodes: A test of the dual vulnerability hypothesis. Cognitive Therapy Research. 2014;38:43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wolitzky-Taylor K, Dour H, Zinbarg R, Mineka S, Vrshek-Schallhorn S, Epstein A, Craske MG. Experiencing core symptoms of anxiety and unipolar mood disorders in late adolescence predicts disorder onset in early adulthood. Depression and Anxiety. 2014;31:207–213. doi: 10.1002/da.22250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Lang NDJ, Ferdinand RF, Verhulst FC. Predictors of future depression in early and late adolescence. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;97:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]