Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive tumor status is associated with improved prognosis after disease recurrence in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC). In this study the potential role of survival bias in the relationship between HPV tumor status and the timing of recurrence was evaluated, given conflicting evidence in the literature.

MATERIALS & METHODS

A secondary analysis was performed on a previously published retrospective two institution study of recurrent OPSCC with known HPV tumor status. Patients were categorized as “early” (surviving <24 months) or “late” survivors (>=24 months). Timing of first recurrence and overall survival were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier and cox proportional hazard methods. Two-sided p-values <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

In total 101 patients met criteria including 81 late and 20 early survivors. HPV-positive tumor status was associated with longer time to recurrence in late survivors (median 21.8 vs. 13.8 months, p=0.028). Late survivors had later recurrences in HPV-positive (p<0.001) and HPV-negative patients (p=0.0096), as well as in both locoregional (p<0.0001) and distant metastatic recurrence (p<0.0001). In multivariate analysis, both HPV-positive tumor status (adjusted HR[aHR] 0.48, p=0.006) and survival beyond 24 months (aHR 0.21, p<0.001) were associated with later recurrence. When stratified, HPV tumor status was only associated with later recurrence in late survivors (aHR 0.47, p=0.015).

CONCLUSIONS

Late survivorship was associated with late recurrence for both HPV-positive and HPV-negative patients. Stratification by survival illustrates how survival bias links late survivorship with late recurrences and contributes to our understanding of the impact of HPV tumor status on the timing of recurrence.

INTRODUCTION

Recent studies have evaluated the impact of human papillomavirus (HPV) tumor status on the clinical presentation and prognosis of recurrent oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC).1–5 The prognostic implication of HPV-positive tumor status at primary diagnosis is well established,6,7 and recent data have also shown that HPV-positive tumor status continues to confer improved prognosis at the time of disease recurrence.1,2,4 However, studies differ on whether or not HPV tumor status is associated with the timing of disease recurrence.8–10

Numerous single institution series and case reports, outside the context of clinical trials, describe late recurrences occurring up to 9 years after primary diagnosis with HPV-related OPSCC. These reports have proposed that late recurrence is a phenomenon specific to HPV-related OPSCC.11–15 However, an analysis of two prospective clinical trials with uniformly treated patient populations revealed similar median time of recurrence, as well as similar upper limits of ranges for time to recurrence for HPV-related and HPV-unrelated OPSCC.1 One possible explanation for the observed later recurrences in HPV-positive OPSCC is that these patients have longer survival, which is necessary for diagnosis or development of a late recurrence.

The question of the timing of disease recurrence in HPV-related OPSCC is important in the context of clinical surveillance guidelines. The surveillance recommendations for OPSCC have not been modified based on HPV tumor status, but if and how they should be modified is an area of current debate. Recent data have suggested that HPV-related recurrences were more often detected on imaging rather than clinical examination or patient symptoms, as compared to HPV-unrelated disease.2 There is a call for practice changes in clinical trial design,16 TNM staging,17,18 and de-intensification of treatment19 based on HPV tumor status. If the timing of recurrence differs by HPV tumor status, then perhaps distinct recommendations for cancer surveillance based upon HPV tumor status should also be considered.

In our recently published retrospective cohort which comprised of patients with recurrent OPSCC, HPV-positive OPSCC recurred later than HPV-negative OPSCC (p=0.001).2 Within this data set, we sought to clarify whether a survival bias contributed to the difference in time to recurrence. We hypothesized that the longer survival of HPV-positive patients may modify the timing of recurrence in these patients and that among patients who experience disease recurrence, those that recur early and late represent distinct subgroups, independent of HPV tumor status.

METHODS

This was an IRB approved retrospective analysis of a previously published patient cohort including patients treated between 2000–2012 at Johns Hopkins Hospital and Greater Baltimore Medical Center.2 Patients diagnosed with recurrent or metastatic oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma or unknown primary squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck with known HPV tumor status were included. Patients with second primary tumors or persistent disease (without a disease-free interval of 3 months after definitive treatment), or with less than 24 months of clinical follow-up, were excluded. HPV tumor status was defined by in situ hybridization or p16 immunohistochemistry as clinically available.20 Pathology and HPV tumor status of recurrent disease was also obtained through medical record abstraction. Recurrent tumors with discordant pathology or HPV tumor status were excluded as second primaries.

A secondary analysis was performed on this patient cohort to examine the time to first recurrence in relation to overall survival time after primary diagnosis. Patients were categorized as “early” or “late” survivors if survival was < 24 months, or ≥24 months after primary diagnosis, respectively. Patients lost to follow up before 24 months were excluded from these analyses. The cutoff of 24 months was based on the median survival of the deceased patients (24.9 months). Recurrences were also categorized as “early” or “late” if diagnosis of disease recurrence was ≤12 months or >12 months after completion of primary therapy, respectively. Clinical variables of interested were retrospectively abstracted from the medical record. These included: age at diagnosis, gender, race, history of tobacco use, nodal stage (N0–N2a vs. N2b–N3), overall staging, HPV tumor status, site of first recurrence (isolated locoregional vs. distant metastatic with or without locoregional) and episodes of recurrence. Episodes of recurrence were defined as either single or multiple episodes over the lifetime or follow up period.

To compare clinical variables of interest, Wilcoxon rank sum tests and chi-square test were used for comparison of medians, and categorical data, respectively. Survival analyses were performed with Kaplan-Meier methods, compared by log-rank test. Multivariate survival analyses used the Cox proportional hazards regression model and accounted for variables statistically significant in univariate analysis and/or of clinical significance. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata 12 software (College Station, Tx). Two sided p-values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Patient cohort

The study population consisted of 101 patients with recurrent OPSCC. Participants were primarily male (86, 81.1%), white (89, 84.0%), and had prior history of smoking (67, 63.2%). A majority of recurrences were locoregional (66, 62.3%). The median follow up time after primary diagnosis was 36.7 months, and the median survival time was 109.9 months. The median time to recurrence was 16.3 months. Histopathologic diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma was confirmed for 90.1% of recurrences. HPV tumor status was available for 54.3% of HPV-positive patients, which confirmed concordance of HPV tumor status of the recurrence.

Early vs. late survivors

The patient cohort was stratified by survivorship. Participants were considered to be early survivors if overall survival was less than 24 months or late survivors if overall survival was 24 months or greater. Based on this stratification, 20 (19.8%) of patients were categorized as early survivors and 81 (80.2%) of patients were late survivors.

A greater proportion of late survivors were HPV-positive as compared to early survivors (p=0.028, Table 1). Late survivors were also younger (median age 56 vs. 59, p=0.023), more commonly male (p=0.025), and had lower nodal stage at primary diagnosis (p=0.068). Early and late survivors were similar in terms of race, smoking history, tumor stage, nodal stage, and overall TNM stage at diagnosis (p>0.1).

Table 1.

Summary of patient characteristics

| Surviving < 24 months n=20; N (%) |

Surviving >=24 months n=81; N (%) |

P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (median, range) | 59 (31–80) | 56 (30–77) | .023 | |||

| Gender: | .025 | |||||

| Male | 13 (65) | 70 (86.4) | ||||

| Female | 7 (35) | 11 (13.6) | ||||

| Race: | .38 | |||||

| White | 16 (80) | 71 (87.7) | ||||

| Black or other | 4 (20) | 10 (12.3) | ||||

| Ever smoker: | .81 | |||||

| Yes | 12 (60) | 51 (62.9) | ||||

| No | 8 (40) | 30 (37) | ||||

| Tumor stage: | .30* | |||||

| T0 | 0 (0) | 4 (4.9) | .34^ | |||

| T1 | 5 (25.0) | 9 (11.1) | ||||

| T2 | 4 (20.0) | 28 (34.6) | ||||

| T3 | 5 (25.0) | 23 (28.4) | ||||

| T4 | 5 (25.0) | 14 (17.3) | ||||

| Unknown | 1 (5.0) | 3 (3.7) | ||||

| Nodal stage: | .038* | |||||

| N0–N2a | 3 (15) | 33 (40.7) | .068^ | |||

| N2b–N3 | 16 (80) | 47 (58) | ||||

| Unknown | 1 (5) | 1 (1.2) | ||||

| Overall TMN stage: | .50* | |||||

| I or II | 1 (5) | 8 (10) | .67^ | |||

| III or IV | 18 (90) | 70 (87.5) | ||||

| Unknown | 1 (5) | 2 (2.5) | ||||

| HPV status: | .028 | |||||

| HPV-negative | 9 (45) | 17 (21) | ||||

| HPV-positive | 11 (55) | 64 (79) | ||||

analysis excluding unknowns

analysis including unknowns

Patterns of recurrence were compared by survivor group (Table 2). Late survivors were less likely than early survivors to have distant recurrence (34.6% vs. 55%, p=0.09). A larger proportion of late survivors had multiple episodes of recurrence as compared to early survivors (45.7% vs. 25%, p=0.087). As would be expected, time to recurrence was significantly associated with survivor group, independent of HPV tumor status (Table 2). A greater proportion of late survivors had a disease-free interval of at least 12 months (late recurrence), as compared to early survivors (80.2% vs. 25%, p <0.001).

Table 2.

Patterns and distribution of recurrence in early vs. late survivors

| Early survivors n=20; N (%) |

Late survivors n=81; N (%) |

HPV-negative (N=26) | HPV-positive (N=75) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P- value |

Early | Late | P- value |

Early | Late | P- value |

|||

| Site of recurrence: | |||||||||

| Locoregional | 9 (45) | 53 (65.4) | .093 | 4 (44.4) | 11(64.7) | .32 | 5 (45.5) | 42(65.6) | .201 |

| Distant | 11 (55) | 28 (34.6) | 5 (55.6) | 6 (35.3) | 6 (54.5) | 22(34.4) | |||

| Number of recurrent episodes: | .087* | .13 | .33* | ||||||

| Single | 14 (70) | 40 (49.4) | .23^ | 7 (77.8) | 8 (47.1) | 7 (63.6) | 32 (50) | .59^ | |

| Multiple | 5 (25) | 37 (45.7) | 2 (22.2) | 9 (52.9) | 3 (27.3) | 28(43.8) | |||

| Unknown | 1 (5) | 4 (4.9) | 0 (0) | 0(0) | 1 (9.1) | 4 (6.2) | |||

| Time to Recurrence: | <.001 | .019 | <.001 | ||||||

| < 12 months | 15 (75) | 16 (19.8) | 8 (88.9) | 7 (41.2) | 7 (63.6) | 9 (14.1) | |||

| >= 12 months | 5 (25) | 65 (80.2) | 1 (11.1) | 10(58.8) | 4 (36.4) | 55(85.9) | |||

statistic excluding unknowns

statistic including unknowns

In the previously published analysis of this cohort, no differences in distribution of sites of first recurrence were observed by HPV tumor status.2 When examining lifetime episodes of recurrences, a similar proportion of HPV-positive and HPV-negative patients experienced multiple recurrences (44.3% vs. 42.3%, p=0.86). Early and late survivors had similar patterns of recurrence (p>0.1, Table 2). Of note, late survivors were more likely to have a late recurrence whether they were HPV-positive (p<0.001) or HPV-negative (p=0.019).

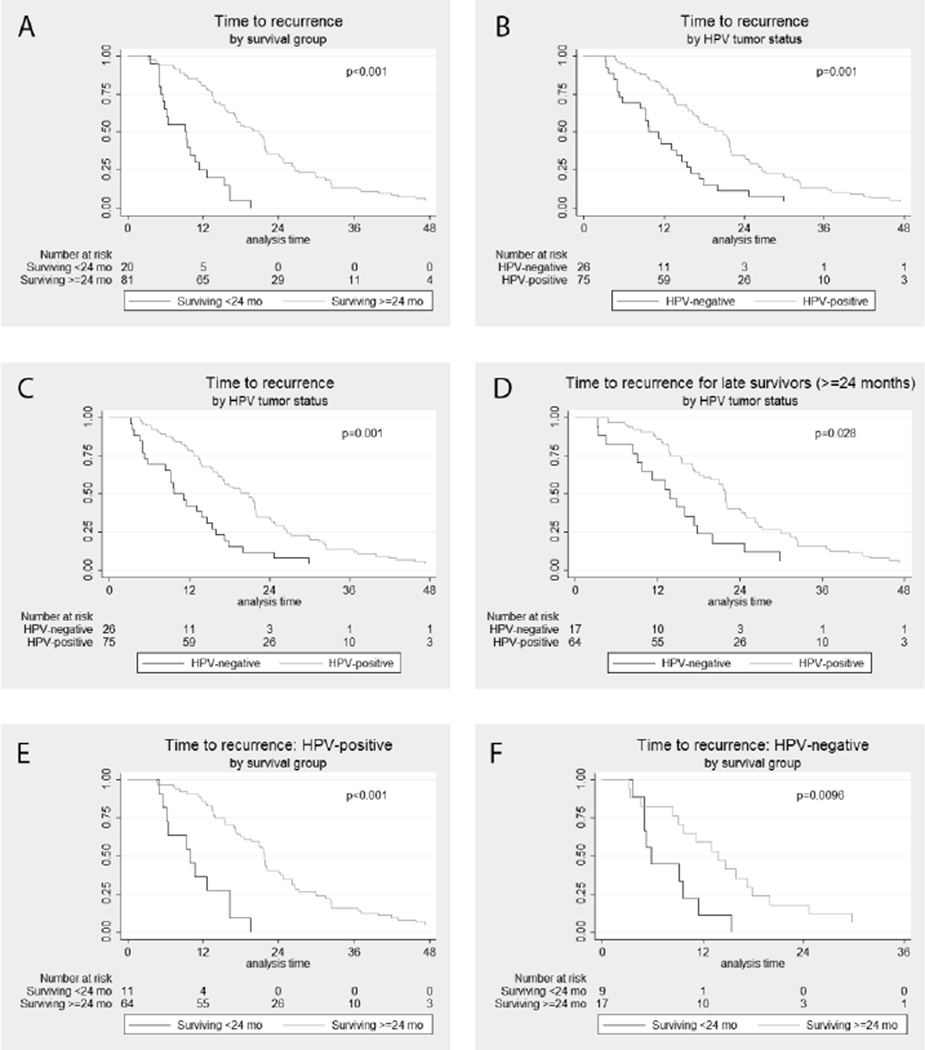

Time to recurrence

The median time to recurrence for late survivors was significantly longer as compared to early survivors (20.9 months vs. 9.2 months, p<0.001 Figure 1A). The median time to recurrence was also longer for HPV-positive compared to HPV-negative patients (19.6 months vs. 9.8 months, p<0.001; Figure 1B) as previously reported.2 To understand the relationship between survivor group and HPV tumor status on the timing of recurrence, a stratified survival analysis was performed (Figure 1C–F). Among early survivors, HPV-positive patients had non-significantly later recurrences than HPV-negative patients (median 9.9 vs. 5.9 months, p=0.086; Figure 1C). Among late survivors, HPV-positive patients had significantly later recurrences than HPV-negative patients (21.8 vs. 13.8 months, p=0.028; Figure 1D). When stratifying by survivor group, the effect of HPV tumor status on time to recurrence was attenuated. However, for both HPV-positive and HPV-negative patients, recurrence was significantly later for late survivors (p<.01; Figures 1E&F).

Figure 1. Time to recurrence.

(A) by survival group (surviving <24 months vs. >=24 months); (B) by HPV tumor status; (C) in patients surviving less than 24 months by HPV tumor status; (D) in patients surviving longer than 24 months by HPV tumor status; (E) HPV-positive patients by survival group; (F) HPV-negative patients by survival group.

Locoregional vs. distant recurrence

Timing of locoregional and distant recurrence were explored in the context of HPV tumor status and survivor group. HPV-positive tumor status was associated with longer time to recurrence for both locoregional (median 20.9 months vs. 9.7 months, p=0.069) and distant metastatic disease (18 months vs. 11.2 months, p=0.0026). Additionally, late survivors had significantly longer time to recurrence for locoregional (20.9 months vs. 9.4 months, p<0.0001) and distant metastatic disease (19 months vs. 6.4 months, p<0.0001). However, among early survivors HPV tumor status was not associated with time to recurrence for either locoregional or distant metastatic disease (p>0.1). By contrast, among late survivors, HPV-positive tumor status was significantly associated with longer time to recurrence for distant metastatic disease (21.8 months vs. 13.8 months, p=0.020), but not locoregional disease (p>0.1).

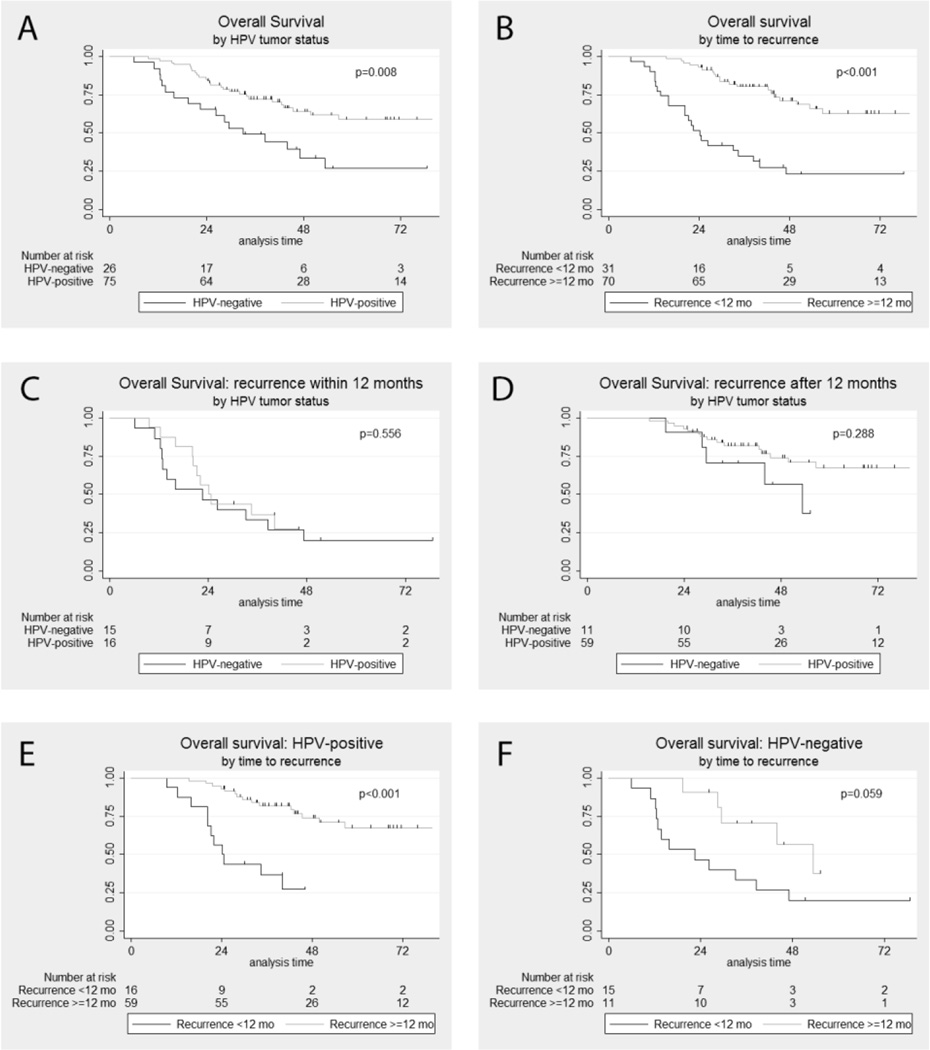

Overall survival

As previously described, HPV-positive tumor status and longer disease free interval (>=12 months, categorized as late recurrence) were both associated with improved overall survival after primary diagnosis (Figure 2A&B).2 The median overall survival was significantly longer for HPV-positive as compared with HPV-negative patients (109.9 vs. 33.1 months, p=0.008) and patients with late recurrence versus early recurrence (126.7 vs. 24.2 months, p<0.001).

Figure 2. Overall survival after primary diagnosis.

(A) by HPV tumor status; (B) by time to recurrence (<12 months vs. >=12 months); (C) in patients recurring within 12 months by HPV tumor status; (D) in patients recurring after 12 months by HPV tumor status; (E) HPV-positive patients by time to recurrence; (F) HPV-negative patients by time to recurrence

To understand the potential effect modification of timing of recurrence on survival, overall survival was evaluated for patients with early recurrence and late recurrence. When patients with early and late recurrence were separately analyzed, HPV tumor status was not associated with overall survival in either group (Figure 2C&D; p>0.1). However, after stratification by HPV tumor status, late recurrence was associated with improved overall survival for both HPV-positive (126.7 vs. 24.2 months, p<0.001; Figure 2E&F) and HPV-negative (median 53.4 vs. 22.5 months, p=0.059) patients.

Multivariate analysis

Time to recurrence was also evaluated using cox proportional hazard models. In univariate analyses only HPV-positive tumor status (HR 0.47 [95%CI 0.30–0.73], p=0.001) and late survivor status (HR 0.18 [0.10–0.32], p<0.001) were significantly associated with longer time to recurrence. Age, gender, smoking history, nodal stage, tumor stage, and site of recurrence (locoregional or distant metastatic) were not associated with time to recurrence (p>0.1). In multivariate analysis, HPV-positive tumor status (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 0.48, p=0.006) and survival greater than 24 months (aHR 0.21, p<0.001) were independently associated with longer time to recurrence (Table 2). Late survivor status was independently associated with longer time to recurrence in both HPV-positive (aHR 0.17, p<0.001) and HPV-negative patients (aHR 0.35, p=0.045). When stratified by survivor group, HPV-positive tumor status was significantly associated with longer time to recurrence for late survivors (aHR 0.47, p=0.015), but not early survivors (p>0.1).

DISCUSSION

The relationship between HPV tumor status and timing of disease recurrence has been a topic of recent controversy. Some series have shown that HPV-positive tumor status is associated with a longer disease free interval and have called for longer period of post-treatment surveillance after primary disease.8,11,12 In contrast, prospectively collected data from RTOG 0129 and 0522 did not show a difference in time to recurrence between HPV-positive and HPV-negative patients.1,9 We therefore explored whether survival bias could help explain these inconsistencies in the literature.

One potential source of survival bias is in the improved overall survival of patients with HPV-positive tumor status, even in the setting of recurrent disease.1,2 As expected, later recurrences were associated with late survival in all elements of this analysis; later survival was strongly correlated with later recurrences for HPV-positive patients (p<0.0001), HPV-negative patients (p=0.0096), locoregional recurrences (p<0.0001), distant metastatic recurrences (p<0.0001) and in multivariate analysis (p<0.0001).

Late survivorship is required to develop late recurrence. The majority of late survivors are HPV-positive, although there are some HPV-negative late survivors. As such, HPV-positive tumor status was associated with longer time to recurrence in the late survivor group. But, in the early survivor group where exposure time to develop a recurrence (2 years) was equal for HPV-positive and HPV-negative patients, the timing of recurrence was statistically similar by HPV tumor status.

The role of survival in the timing of recurrences was also suggested when looking at the number of episodes of recurrence experienced by patients. Notably, patients who were late survivors were more likely to have multiple episodes of recurrence (45.7% vs. 25%). Although multiple recurrences with multiple prior treatments might be expected to be correlated with worse prognosis,21,22 patients who survive longer have greater exposure time, e.g. contribute greater person years at risk, to accumulate multiple recurrences.

Based on the published RTOG data where the longest time to recurrence was similar in HPV-positive (74.8 months) and HPV-negative patients (80.0 months), late recurrences in HPV-negative patients do occur.9 However, these late recurrences are likely less common due to the shorter survival of HPV-negative patients, as previously discussed. Looking specifically at distant metastatic recurrences, some of the differences in the literature may potentially be explained by the relatively smaller numbers of HPV-negative patients included (n=12–25) and correspondingly few cases of HPV-negative late recurrences (n=0–1). However, the RTOG study included the largest cohort of HPV-negative patients with distant metastatic recurrences (n=33), with 15% (n=5) of these cases occurring beyond 2 years. In the context of this larger cohort, this study did not report differences in time to progression based on HPV tumor status.1

In our previously published analysis, we observed that longer disease-free interval was significantly associated with improved overall survival after recurrence.2 In view of this relationship, we hypothesized that among HPV-positive and HPV-negative patients with recurrence, those that recur early and late represent distinct subgroups. Indeed, we found that dividing patients into those who recur early (<12 months) and late (≥12 months) defined two distinct populations. When patients were stratified by recurrence group, HPV-positive tumor status was no longer associated with longer overall survival for either early (p=0.528) or late recurrences (p=0.288). Rather, survival was more strongly defined by the timing of recurrence where those who recurred later than 12 months had significantly better overall survival independent of HPV tumor status.

In this study late survivors, whether HPV-positive or HPV-negative, are susceptible to late recurrence and could benefit from continued surveillance. Current clinical practice guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommend a surveillance schedule of every 1–3 months for the first year, 2–6 months for the second year, 4–8 months for the third through fifth years, and annually thereafter.23 While historical 5-year survival rates may not have warranted close surveillance beyond five years,24 the improved survival of the contemporary head and neck population may require revised recommendations.17 We observed that patients with later recurrences had improved overall survival within existing clinical practice. It would be of interest to determine whether changes in surveillance strategies in later years would ultimately impact overall survival.

This secondary analysis has significant limitations. Survival is closely associated with time to recurrence and HPV tumor status. Therefore, in some cases the outcome and exposure variable are closely related. This weakness is acknowledged and utilized to illustrate the relationships of interest and contextualize prior literature as well as previous conclusions. This study was performed to help explain some of the perceived differences and elucidate biases. The retrospective nature of the patient cohort inherently introduces potential for selection biases and limits data available to be incorporated into the present analysis, including patient comorbidities and performance status. Additionally, it is important to point out that the various tabulations and stratifications resulted in smaller subsets, which may have limited power to discern differences. These smaller subsets may not be fully representative of larger clinical populations. Lastly, distinguishing between recurrent disease and second primary disease can be challenging in a retrospective study, particularly in late recurrences. In this study, pathology of recurrent tumors was available in 90% of tumors to confirm squamous cell carcinoma, and HPV tumor status was available for 54% of HPV-positive patients to distinguish from second primaries. Furthermore, previous studies have shown that among HPV-positive patients second primaries are infrequent and recurrent disease is HPV-positive in 92–97% of cases, including lung metastases.25,26

In conclusion, while HPV-positive tumor status has been associated with late recurrences, the long survivorship of HPV-positive patients exaggerates this effect. Late survivorship is independently associated with late recurrence for both HPV-positive and HPV-negative patients. The framework of early and late survivors illustrates the contribution of survival bias to better inform our understanding of the interplay between HPV tumor status and the timing of disease recurrence.

Table 3.

Multivariate cox regression model for time to recurrence

| Overall | Stratified by HPV tumor status | Stratified by survivor group | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV-positive | HPV-negative | Survival <24 mo | Survival >=24 mo | ||||||||

| Variable | HR (95%CI) | P | HR (95%CI) | P | HR (95%CI) | P | HR (95%CI) | P | HR (95%CI) | P | |

| HPV tumor status | 0.006 | - | - | - | - | 0.21 | 0.015 | ||||

| Negative | REF | REF | REF | ||||||||

| Positive | 0.48 (.29–.81) |

0.53 (.19–1.44) |

0.47 (.25–.86) |

||||||||

| Age at diagnosis (per year) | 1.02 (.99–1.04) |

0.16 | 1.01 (.98–1.03) |

0.73 | 1.03 (.99–1.07) |

0.13 | 1.05 (.979–1.11) |

0.20 | 1.01 (.99–1.04) |

0.31 | |

| Gender | 0.80 | 0.19 | 0.67 | 0.34 | 0.52 | ||||||

| Female | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | ||||||

| Male | 1.08 (.61–1.90) |

0.63 (.32–1.3) |

1.23 (.48–3.12) |

0.61 (.22–1.69) |

1.26 (.63–2.56) |

||||||

| Survival (months) | <.001 | <.001 | 0.045 | - | - | - | - | ||||

| <24 | REF | REF | REF | ||||||||

| ≥24 | 0.21 (.11–.37) |

0.17 (.08–.35) |

0.35 (.13–.98) |

||||||||

Highlights.

We examine the role of survival bias in relating HPV and timing of recurrence.

A stratified analysis shows how late survivorship is associated with late recurrence.

Late survivors, independent of HPV tumor status, may experience late recurrences.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by P50DE019032, 2T32DC000027-26, Oral Cancer Foundation and the Milton J Dance Jr. Head and Neck Center.

Abbreviations

- HPV

human papillomavirus

- OPSCC

oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma

- aHR

adjusted hazard ratio

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared

All the authors have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence (bias) their work, and nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Fakhry C, Zhang Q, Nguyen-Tan PF, et al. Human papillomavirus and overall survival after progression of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014 Oct 20;32(30):3365–3373. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo T, Qualliotine JR, Ha PK, et al. Surgical salvage improves overall survival for patients with HPV-positive and HPV-negative recurrent locoregional and distant metastatic oropharyngeal cancer. Cancer. 2015 Mar 17; doi: 10.1002/cncr.29323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel SN, Cohen MA, Givi B, et al. Salvage surgery of locally recurrent oropharyngeal cancer. Head Neck. 2015 Apr 13; doi: 10.1002/hed.24065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Argiris A, Li S, Ghebremichael M, et al. Prognostic significance of human papillomavirus in recurrent or metastatic head and neck cancer: an analysis of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trials. Ann. Oncol. 2014 Jul;25(7):1410–1416. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spreafico A, Amir E, Siu LL. Demystifying the role of tumor HPV status in recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Ann. Oncol. 2014 Apr;25(4):760–762. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010 Jul 1;363(1):24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fakhry C, Westra WH, Li S, et al. Improved survival of patients with human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2008 Feb 20;100(4):261–269. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Sullivan B, Adelstein DL, Huang SH, et al. First Site of Failure Analysis Incompletely Addresses Issues of Late and Unexpected Metastases in p16-Positive Oropharyngeal Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015 Mar 30; doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fakhry C, Zhang Q, Nguyen-Tan PF, et al. Reply to B. O'Sullivan et al. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015 Mar 30; doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.3555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pfister DG, Baxi SS, Dunn LA, Fury MG. Reply to B. O'Sullivan et al. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015 Mar 30; doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.3563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang SH, Perez-Ordonez B, Liu FF, et al. Atypical clinical behavior of p16-confirmed HPV-related oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma treated with radical radiotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2012 Jan 1;82(1):276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang SH, Perez-Ordonez B, Weinreb I, et al. Natural course of distant metastases following radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy in HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2013 Jan;49(1):79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruzevick J, Olivi A, Westra WH. Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma to the brain: an unrecognized pattern of distant spread in patients with HPV-related head and neck cancer. J. Neurooncol. 2013 May;112(3):449–454. doi: 10.1007/s11060-013-1075-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trosman SA-KS, Koyfman SA, et al. Distant metastatic failure patterns in squamous cell cancer of the oropharynx (SCCOP) treated with chemoradiation: the impact of human papillomavirus (HPV) Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2014;88(2):471. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sinha P, Thorstad WT, Nussenbaum B, et al. Distant metastasis in p16-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: a critical analysis of patterns and outcomes. Oral Oncol. 2014 Jan;50(1):45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu JC, Ridge JA, Brizel DM, et al. Current Status of Clinical Trials in Head and Neck Cancer 2014. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2015 Mar;152(3):410–417. doi: 10.1177/0194599814566595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang SH, Xu W, Waldron J, et al. Refining American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union for International Cancer Control TNM stage and prognostic groups for human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal carcinomas. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015 Mar 10;33(8):836–845. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.6412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keane FK, Chen YH, Neville BA, et al. Changing prognostic significance of tumor stage and nodal stage in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx in the human papillomavirus era. Cancer. 2015 Apr 14; doi: 10.1002/cncr.29402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Sullivan B, Huang SH, Siu LL, et al. Deintensification candidate subgroups in human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal cancer according to minimal risk of distant metastasis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013 Feb 10;31(5):543–550. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Begum S, Gillison ML, Ansari-Lari MA, Shah K, Westra WH. Detection of human papillomavirus in cervical lymph nodes: a highly effective strategy for localizing site of tumor origin. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003 Dec 15;9(17):6469–6475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weichselbaum RR, Beckett MA, Schwartz JL, Dritschilo A. Radioresistant tumor cells are present in head and neck carcinomas that recur after radiotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 1988 Sep;15(3):575–579. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(88)90297-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho AS, Kraus DH, Ganly I, Lee NY, Shah JP, Morris LG. Decision making in the management of recurrent head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2014 Jan;36(1):144–151. doi: 10.1002/hed.23227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Network NCC. Head and Neck Cancer (Version 2.2014) [Accessed October 6, 2014];National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. 2014 http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/head-and-neck.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodwin WJ., Jr Salvage surgery for patients with recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the upper aerodigestive tract: when do the ends justify the means? Laryngoscope. 2000 Mar;110(3 Pt 2) Suppl 93:1–18. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200003001-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bishop JA, Ogawa T, Chang X, et al. HPV analysis in distinguishing second primary tumors from lung metastases in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:142–148. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182395c7b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vainshtein J, McHugh JB, Spector ME, et al. Human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal cancer: HPV and p16 status in the recurrent versus parent tumor. Head Neck. 2015;37:8–11. doi: 10.1002/hed.23548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]