Abstract

Bisphosphonates have been widely used in the treatment of osteoporosis with robust data from many placebo-controlled trials demonstrating its efficacy in fracture risk reduction over 3 to 5 years of treatment. Although bisphosphonates are generally safe and well tolerated, concerns have emerged about the adverse effects related to its long-term use, including osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femur fractures. Because bisphosphonates are incorporated into the skeleton and continue to exert an anti-resorptive effect for a period of time after the discontinuation of drugs, the concept of a "drug holiday" has emerged, whereby the risk of adverse effects might be decreased while the patient still benefits from anti-fracture efficacy. As randomized clinical trial evidence is not yet available on who may qualify for a drug holiday, there is considerable controversy regarding the selection of candidates for the drug holiday and monitoring during a drug holiday, both of which should be based on individual assessments of risk and benefit. This statement will provide suggestions for clinicians in South Korea on the identification of possible candidates and monitoring during a bisphosphonate drug holiday.

Keywords: Diphosphonates, Drug holiday, Fractures bone, Osteoporosis

INTRODUCTION

Bisphosphonates decrease bone resorption by inhibiting osteoclast function.[1] Robust data from many placebo-controlled trials have also demonstrated the efficacy of bisphosphonates in fracture risk reduction with a vertebral fracture risk reduction ranging from 40% to 70% and relative hip fracture reduction of 40% to 70% over 3 to 5 years of treatment.[2] Bisphosphonates have been the most widely used agent in South Korea (about 80%) for the treatment of osteoporosis.[3] Bisphosphonates are generally safe and well tolerated. However, some unexpected possible adverse effects have been reported, including osteonecrosis of the jaw [4] and atypical femoral fractures.[5] Because bisphosphonates are incorporated into the skeleton and continue to exert an anti-resorptive effect for a period of time after the discontinuation of drugs, the concept of a drug holiday has emerged, whereby the risk of adverse effects might be decreased while the patient still benefits from anti-fracture efficacy.[6] However, there is considerable controversy regarding the optimal selection of candidates for the drug holiday and monitoring during a drug holiday, both of which should be based on individual assessments of risks and benefits. In addition, responsiveness to anti-resorptive effects differs between the Asian population and the white population, possibly owing to genetic, dietary, and environmental differences.[7,8,9] Hence, we propose a potential algorithm to guide physicians in South Korea, despite no available clear recommendations regarding the length of use and drug holidays based on the current research. These statements cannot and should not be used to govern health policy decisions about reimbursement or the availability of services. Furthermore, this statement is also not intended as rigid standards of practice.

1. The drug holiday concept

A. A drug holiday should be viewed as a temporary, not permanent, suspension of active therapy.

B. It should be remembered that discontinuing a bisphosphonate may not necessarily be a "holiday" from treatment because persistence of the anti-resorptive effect is expected for an undefined period of time.

C. Selection of candidates for the drug holiday and monitoring during a drug holiday needs to be tailored to the individual patients.

It is unusual to contemplate a drug holiday in the treatment of most chronic diseases because with most therapies, beneficial drug effects rapidly diminish with discontinuation. However, the long skeletal residence time of bisphosphonates and concern about the risks of rare adverse events with long-term therapy raise the possibility that bisphosphonate therapy may be interrupted for a "drug holiday," during which anti-fracture benefit might persist for a period of time while the potential risks are minimized.[6]

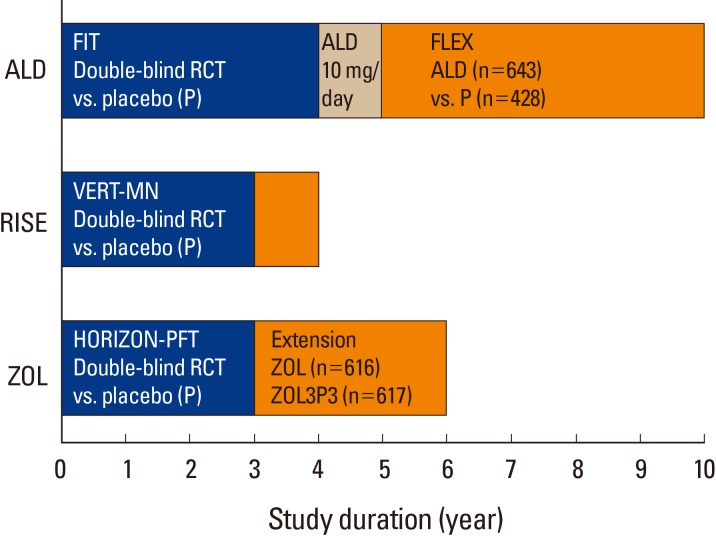

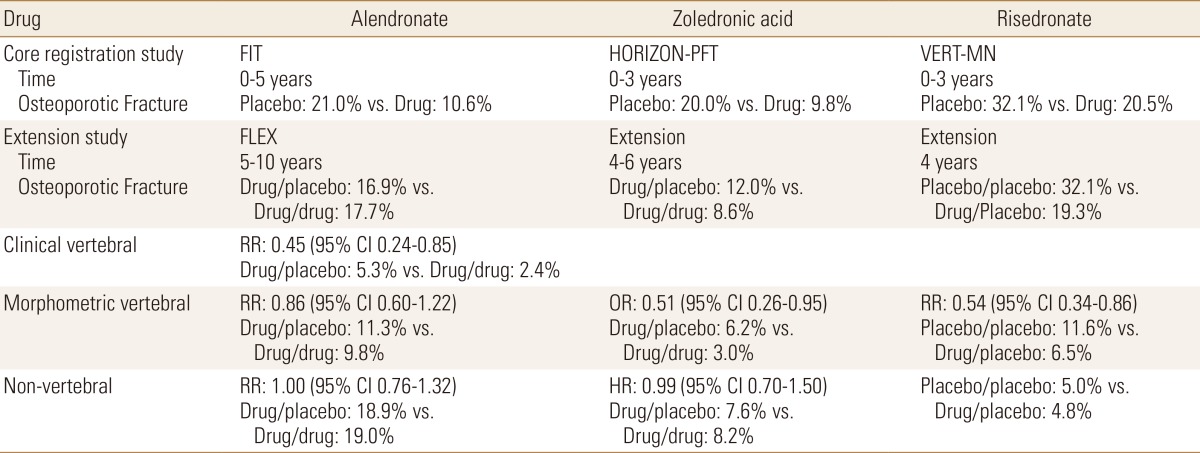

The first question is whether stopping bisphosphonates is safe in regard to maintaining adequate prevention against developing osteoporotic fractures. Indeed, bisphosphonates are deposited in bones for at least 10 years, and when a bone containing bisphosphonate is resorbed, the bisphosphonate recirculates locally and systemically and is able to bind again to bone surfaces. Bone resorption continues to be inhibited over time, and the anti-resorptive effect persists after the drug has been stopped.[10] In assessing the maintenance of adequate prevention against developing osteoporotic fractures after stopping bisphosphonates, it would be ideal to have clinical trial data comparing fracture risk between patients who continue or stop therapy; unfortunately, only three prospective studies have addressed this issue (Fig. 1).[11,12,13] In the Fracture Intervention Trial (FIT) Long-term Extension Trial (FLEX) (Table 1), subjects on alendronate for more than 5 years were randomized to either continue alendronate therapy for a total of 10 years or discontinue therapy after 5 years.[12] Although the subject number was small, those continuing alendronate for 10 years had fewer clinical vertebral fractures than the subjects receiving the drug for only 5 years (5.3% vs. 2.4%, respectively). There was no difference between the groups for morphometric vertebral or non-vertebral fractures. In the Health Outcomes and Reduced Incidence with Zoledronic Acid Once Yearly (HORIZON)-Pivotal Fracture Trial (PFT; HORIZON-PFT) (Table 1), subjects on zoledronic acid for 3 years were randomized to stop therapy or to continue on yearly zoledronic acid for 3 additional years.[11] Treatment for 3 additional years resulted in a 52% lower risk of morphometric vertebral fracture, compared with treatment for 3 years followed by placebo for the next 3 years (fracture rates 3.0% vs. 6.2%, respectively). The risks of other fractures-including clinical or symptomatic vertebral fractures-did not differ between the groups. In the Vertebral Efficacy with Risedronate Therapy-Multinational (VERT-MN), a small number of patients were given risedronate or placebo for 3 years and then followed for an additional one year after discontinuation (Table 1); the morphometric vertebral fracture incidence remained 46% lower in the former risedronate group, as compared with the former placebo group (6.5% vs. 11.6%, respectively).[13] However, there was no group of patients continuing on risedronate, hence it was not possible to compare the fracture risk of discontinuing therapy with continuing therapy (Table 1).

Fig. 1. Summary of published study designs for the long-term trials with bisphosphonate treatments with fracture-related end points.[11,12,13] ALD, alendronate; FIT, fracture intervention trial; RCT, randomized controlled trial; FLEX, fracture intervention trial long-term extension trial; RISE, risedronate; VERT-MN, vertebral efficacy with risedronate therapy-multinational; HORIZON-PFT, health outcomes and reduced incidence with zoledronic acid once yearly-pivotal fracture trial; ZOL, zoledronic acid.

Table 1. Efficacy of bisphosphonate from extension trials.

FIT, fracture intervention trial; HORIZON-PFT, health outcomes and reduced incidence with zoledronic acid once yearly-pivotal fracture trial; VERT-MN, vertebral efficacy with risedronate therapy-multinational; FLEX, fracture intervention trial long-term extension trial; RR, relative risk; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; OR, odd ratio; HR, hazard ratio.

The second question is whether stopping bisphosphonates reduce the risk of complications. In assessing the reduction of risk of complications after stopping bisphosphonates, it would be helpful to have clinical trials comparing the rates of adverse and serious adverse experiences in subjects randomized to continuing or discontinuing bisphosphonate therapy. It stands to reason that if rare undesirable medical occurrences are causally related to bisphosphonate use, then the risk should diminish over time as the bisphosphonate is eliminated from the bone. However, apart from the Swedish study suggesting that the risk of atypical femoral fractures decreases following discontinuation of oral bisphosphonate,[14,15] there are no data to answer this question.

Those data suggest the following after bisphosphonate exposure of 3 to 5 years in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: the protection from fractures persists for an unknown interval of time in selected patients when therapy is withdrawn; that the protection wanes within 3 to 5 years of discontinuation; and that the risk of atypical femoral fractures increases with the duration of therapy but may decrease upon withdrawal of treatment. There are limited data to guide decision-making about the initiation and termination of "drug holidays." Currently, an observational study is in process to compare the effects on bone quantity and quality during a 2-year drug holiday after 2 years of bisphosphonate use (NCT01406613). However, until these results are available and randomized controlled clinical trials are published, physicians are asked to use their best clinical judgment to determine who qualifies for a drug holiday. In the absence of clear evidence, any recommendations for the selection of candidates for the drug holiday and monitoring during a drug holiday can only be "expert opinion" and should be individualized according to a consideration of all available clinical information.

Furthermore, a drug holiday should be viewed as a temporary, not permanent, suspension of active therapy. It should be remembered that discontinuing a bisphosphonate might not necessarily be a "holiday" from treatment, because persistence of the anti-resorptive effect is expected for an undefined period of time.

2. Considerations for the drug holiday

-

A. Determination of the duration for bisphosphonate therapy.

- i. Drug holiday from alendronate and risedronate may be considered after 5 years.

- ii. Drug holiday from zoledronic acid may be considered after 3 years.

-

B. Selection of the appropriate candidates for the drug holiday.

- i. Consider a drug holiday after 5 years of alendronate and risedronate treatment, and after 3 years of zoledronic acid, in individuals without high risk.

-

ii. Consider the continued treatment in individuals with high risk.

- 1) T-score at any site still ≤-2.5 after bisphosphonate therapy (5 years for alendronate and risedronate, and 3 years for zoledronic acid).

- 2) Previous fracture of the hip or spine.

- 3) High risk of fracture because of secondary osteoporosis from chronic diseases or medication.

- iii. Alternative therapy may be used for individuals with high risk.

- iv. Factors guiding the determination of a drug holiday are the variable anti-resorptive potency and binding affinity of each bisphosphonate, as well as a demonstration of compliance with the therapy.

In regard to determination of the optimal duration for bisphosphonate therapy, there are only 3 prospective studies containing information about fracture risk upon discontinuing bisphosphonate therapy, such as alendronate, risedronate, and zoledronic acid.[11,12,13] There is no information about fracture risk upon discontinuing ibandronate therapy. Hence, we suggest that the drug holiday may be considered after 5 years from alendronate and risedronate and after 3 years from zoledronic acid.

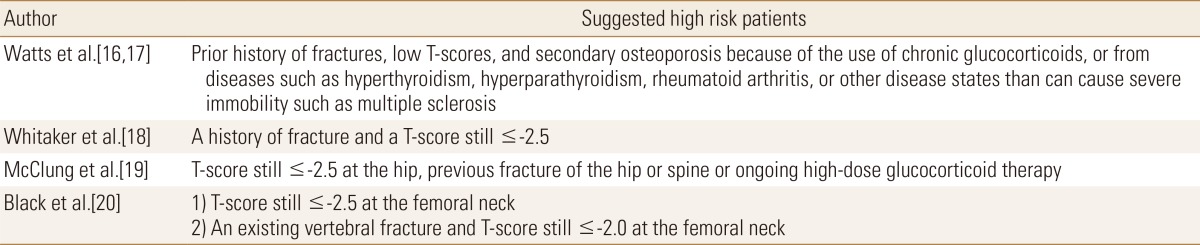

In regard to selection of the appropriate candidates for drug holiday, there have been some suggestions (Table 2). One study proposed to stratify patients based on their known or potential risk of fracture.[16] High-risk patients include patients with prior history of fractures, low T-scores, and secondary osteoporosis because of the use of chronic glucocorticoids, or from diseases such as hyperthyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, rheumatoid arthritis, or other disease states than can cause severe immobility, for instance, multiple sclerosis. In those kinds of patients, it was recommended continuing bisphosphonate therapy for up to 10 years, and then a drug holiday could be considered (Table 2). If a holiday from the bisphosphonate in high-risk patients is considered after 10 years, interval treatment with other agents, such as parathyroid hormone or selective estrogen receptor modulator, may be warranted.[16] In moderate-risk patients, they suggested drug holiday after 5 to 10 years and in low-risk patients after 3 to 5 years of bisphosphonate therapy. Bisphosphonates should then be resumed if bone mineral density (BMD) decreases or the patient has a fracture. The duration of a drug holiday is unknown, but the authors propose 1 to 2 years in high-risk patients, 3 to 5 years in moderate-risk, and indefinitely in low-risk patients. This proposal was also cited in the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) guideline.[17]

Table 2. Suggested high-risk patients who were considered the continued treatment after the adequate duration of treatment.

Recently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an advisory to provide additional guidance to physicians.[18] The FDA analyzed the 3 long-term extension trials: FLEX, HORIZON-PFT, and VERT-MN. Although the primary endpoint in the extension trials was BMD, the FDA analyses included both BMD and fracture outcomes (vertebral and non-vertebral). In their review of FLEX, the panel reported that the rates of vertebral and non-vertebral osteoporotic fractures were similar whether participants continued to receive alendronate for up to 10 years or were switched to a placebo. Also, the panel noted that fracture rates appear to be constant when all data on vertebral and non-vertebral osteoporotic fractures with long-term therapy are pooled from the 3 extension trials. For example, in patients who received continuous bisphosphonate treatment for at least 6 years, the fracture rates ranged from 9.3% to 10.6%, whereas the rate for patients switched to a placebo was 8.0% to 8.8%. These data question the benefit of extended therapy with bisphosphonates after 5 years of fracture prevention. Therefore, the FDA recommended periodic assessment of a patient's need for continued therapy, taking into account their individual risks and benefits and patient preference to optimize the efficacy of bisphosphonates in reducing fracture risk. In this regard, patients at low risk for fracture (e.g., younger patients without a fracture history and with a BMD approaching normal) may qualify for drug holiday after 3 to 5 years, whereas patients at higher risk of fracture (e.g., older patients with a history of fracture and a BMD remaining in the osteoporotic range) may benefit from continued bisphosphonate therapy (Table 2). These recommendations were also suggested by other groups.[19]

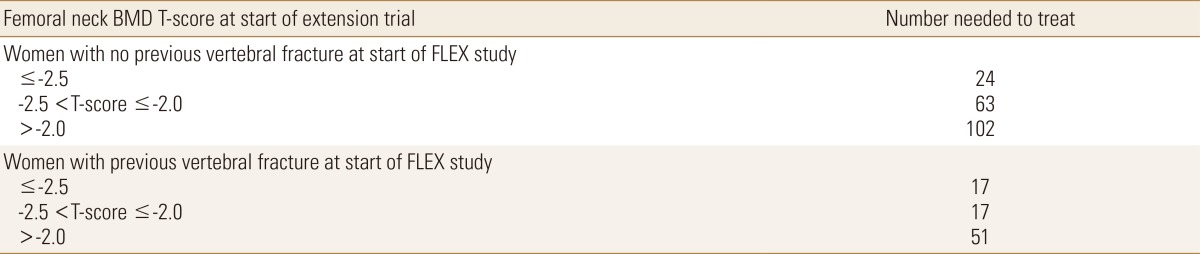

The response to the FDA advisory commented that the FDA analysis focused on the composite end point of all fractures, both vertebral and non-vertebral, when the original preplanned analyses of the extension studies separated vertebral and non-vertebral fractures because of "their distinct pathogenesis and different responses to treatment".[20] According to that analysis, the risk for vertebral fractures was shown to be reduced with continued bisphosphonate therapy beyond 3 to 5 years, whereas evidence was lacking for non-vertebral fractures. Data from FLEX was used to estimate the number needed to treat (for 5 additional years) to prevent one clinical vertebral fracture (in subgroups defined by BMD at the femoral neck and by prevalent vertebral fractures status at entry in FLEX) (Table 3). The risk of vertebral fracture is highest and the numbers needed to treat are lowest for patients with a femoral neck T-score ≤-2.5, which suggests that it may reasonably be expected that these patients would benefit by continuing bisphosphonate therapy. In addition, patients with a preexisting vertebral fracture with a femoral neck T-score ≤-2.0 may also benefit from continuation (Table 2). Thus, in general, we consider that the following individuals are at a high risk for fractures and appear to benefit most from continuation of bisphosphonates: those with a T-score at any site still ≤-2.5 after bisphosphonate therapy (5 years for alendronate and risedronate, and 3 years for zoledronic acid), previous fracture of the hip or spine, or secondary osteoporosis from chronic diseases or medication. Alternative therapy (e.g., parathyroid hormone or selective estrogen receptor modulator) may be used for individuals with a high risk. Individuals without a high risk for fractures are unlikely to benefit from continued treatment after bisphosphonate therapy for 3 to 5 years.

Table 3. Risk of clinical vertebral fracture and number needed to treat to prevent one clinical vertebral fracture for 5 years in FLEX study.

BMD, bone mineral density; FLEX, fracture intervention trial long-term extension trial. [Modified from "Continuing bisphosphonate treatment for osteoporosis-for whom and for how long?", by Black DM, Bauer DC, Schwartz AV, Cummings SR, Rosen CJ., 2012, N Engl J Med, 366, pp.2051-3. Copyright 2012 by the NEJM. Reprinted with permission].

Furthermore, there are some considerable factors guiding the determination of drug holiday, such as the variable anti-resorptive potency and binding affinity of each bisphosphonate, and a demonstration of compliance with the therapy. The variable anti-resorptive potency and binding affinity of each bisphosphonate are owing to their unique side chains. Zoledronic acid has the highest potency, followed by risedronate, ibandronate, and alendronate. Binding affinity is highest for zoledronic acid and decreases in order of magnitude for alendronate, ibandronate, and risedronate, respectively.[1,16] This may be owing to a greater affinity of alendronate and zoledronic acid to hydroxyapatite, compared with risedronate and ibandronate.[21] The skeletal binding sites for bisphosphonate are nearly unsaturable, thereby leading to a significant accumulation of bisphosphonates whereas release of bisphosphonates may be small, as it partly depends on bone turnover, which is reduced by the use of bisphosphonates.[21] For example, after 10 years of alendronate use at a dose of 10 mg daily (70 mg weekly), the amount of alendronate released over several months or years would be equivalent to taking one-quarter of the usual dose.[22] In general, zoledronic acid and alendronate maintain a prolonged effect after discontinuation, whereas others, such as risedronate, have a more rapid offset.[21] Another factor to consider in the drug holiday is a demonstration of compliance with the therapy. A recent retrospective register study about the residual treatment effect of alendronate and risedronate in Swedish clinical practice suggests that the duration of bisphosphonate therapy is significantly inversely associated with the incidence of hospitalized fractures following discontinuation.[23] Specifically, during the first 6 months after terminating treatment, the adjusted fracture rates were considerably lower in patients who had been persistent with treatment for more than 12 months, compared with those who had stopped treatment within 1 month (hazard ratio [HR]=0.40). It is known that 70% of bisphosphonate users discontinued their prescriptions after 1 year of use in South Korea.[3] Therefore, the decision to go on drug holiday after 3 to 5 years should be after assurance of continuous use of bisphosphonates during the initial therapy period.

3. Monitoring during a drug holiday

-

A. Parameter for monitoring during a drug holiday

- i. Consider the annual measurement of BMD using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry.

-

B. Restart therapy after a drug holiday

- i. Consider re-treatment if there is a significant decrease in BMD.

- ii. Consider re-treatment if T-score reaches ≤-2.5 or a new osteoporotic fracture occurs.

There are no data providing information on how to monitor patients or when to restart therapy after a drug holiday. In the absence of guidance from clinical trials, empiric approaches are necessary. Although the approach has not been studied, BMD and biochemical markers of bone turnover (BTMs) measured after discontinuation may provide information about the persistence of the effect of the retained bisphosphonate. A significant decrease in BMD or a significant increase in BTMs suggests that the benefits of bisphosphonate therapy may be diminishing and that it may be time to return to active therapy.[24] A recent study, a post hoc analysis of FLEX participants randomized to placebo after receiving 5 years of oral alendronate therapy,[25] showed that older age and lower total hip BMD at the time of discontinuation were associated with higher rates of clinical fracture during the next 5 years, but neither 1-year changes in BMD nor 1- and 3-year changes in BTMs levels (urinary type 1 collagen cross-linked N-telopeptide and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase) were associated with fracture risk. Similarly, most associations between 2- or 3-year changes in BMD and fracture risk were not statistically significant, although there were fewer fractures after the second (n=70) and third (n=57) annual visits included in the analysis. The risk of fracture was elevated among those with greater total hip bone loss after 2 or 3 years of follow-up, but after adjustment for age and baseline BMD at the time of discontinuation, only the 2-year total hip bone loss greater than 3% was significantly associated with fracture risk (relative HR=1.68, 95% confidence interval=1.05-2.72). Neither a 2- or 3-year change in BMD at the femoral neck nor a 3-year change in BMD at the lumbar spine was associated with fracture risk. Therefore, more research is needed about the role of serial bone density testing and BTMs in monitoring fracture risk after therapy cessation, as well as the optimal therapies to use following a drug holiday. Another untested approach is to reevaluate the patient after discontinuation, thereby making the decisions to restart therapy based on an updated assessment of fracture risk using algorithms initially developed for untreated individuals. For example, if the patient has a T-score ≤-2.5, or if the patient has a T-score between -1.0 and -2.5 and a World Health Organization's Fracture Risk Assessment estimate of fracture risk that meets treatment guidelines, then consider reinitiating therapy. If, at any time during the drug holiday there is a fracture, restarting therapy (not necessarily a bisphosphonate) is advised. Monitoring with BMD and BTMs after discontinuation of alendronate therapy does not appear to improve fracture prediction, however, we propose the annual measurement of BMD and consideration of re-treatment if there is a significant decrease in BMD, a T-score reaches ≤-2.5, or new osteoporotic fracture occurs.

4. Remaining questions

Randomized clinical trial evidence is not yet available on who may qualify for a drug holiday, thus many additional issues urgently need epidemiologic, clinical, and economic research in the Korea. For example, the following several issues need to be addressed.

More research is needed about the length of time for which bisphosphonate treatments continue to work after they are stopped.

Does stopping bisphosphonates reduce the risk of complications such as osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femur fractures?

How can the optimal duration of a drug holiday be determined for other bisphosphonates therapy such as ibandronate or pamidronate?

How can we better identify the individuals at high risk for fractures who may benefit from continued bisphosphonate therapy?

Is there is a need to stratify patients based both on the femoral neck T-score, but not on the lumbar spine T-score and the preexisting vertebral fracture status?

What approaches are most effective in treating osteoporosis in individuals with high risk?

Is there any difference in the optimal duration of a drug holiday according to each bisphosphonate with variable anti-resorptive potency and binding affinity?

How can patients be better monitored after a drug holiday?

When can therapy be restarted after a drug holiday?

More research is needed about the role of serial BMD testing and BTMs in monitoring fracture risk after a drug holiday, as well as the optimal therapies to use following a drug holiday.

CONCLUSION

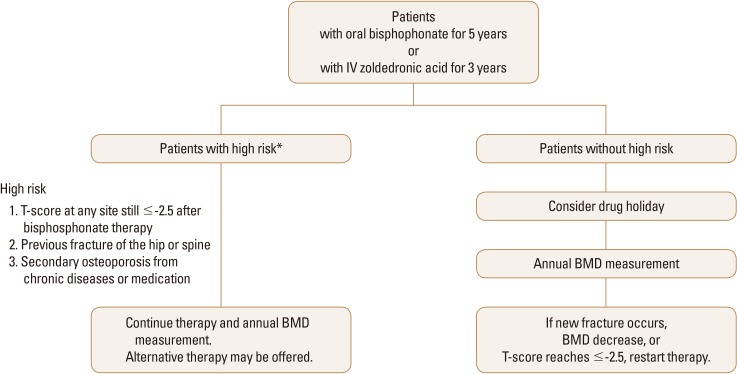

Though bisphosphonates are commonly used in the prevention of fracture and treatment of osteoporosis in South Korea, there remains much controversy surrounding its potential side effects from prolonged use. Until further evidence is published, there are no clear recommendations regarding the length of use and drug holidays. Based on the current research, a potential algorithm to guide physicians in South Korea is proposed (Fig. 2). If the patient does not have a high risk for fractures, then a drug holiday was considered after 3 to 5 years (5 years for alendronate and risedronate and 3 years for zoledronic acid). During the drug holiday, patients were re-evaluated for risk of fracture with an annual measurement of BMD. If patient meets the criteria for therapy (such as a significant decrease in BMD, T-score ≤-2.5, or new osteoporotic fracture), then re-start a treatment. If the patient has a high risk of fractures (T-score at any site still ≤-2.5 after bisphosphonate therapy, previous fracture of the hip or spine, or high risk of fracture because of secondary osteoporosis from chronic diseases or medication), then can maintain a drug depending on their BMD and fracture status.

Fig. 2. Proposed algorithm for the selection of candidates for drug holidays and principles of monitoring. BMD, bone mineral density.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Russell RG, Watts NB, Ebetino FH, et al. Mechanisms of action of bisphosphonates: similarities and differences and their potential influence on clinical efficacy. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:733–759. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0540-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eastell R, Walsh JS, Watts NB, et al. Bisphosphonates for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Bone. 2011;49:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Korean Endocrine Society. Osteoporosis fact sheet 2014. 2014. [cited by 2015 September 1]. Available from: http://www.endocrinology.or.kr/image/main/kor_Osteoporosis_Fact_Sheet2014.pdf.

- 4.Khan AA, Morrison A, Hanley DA, et al. Diagnosis and management of osteonecrosis of the jaw: a systematic review and international consensus. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30:3–23. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shane E, Burr D, Abrahamsen B, et al. Atypical subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femoral fractures: second report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:1–23. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonnick SL. Going on a drug holiday? J Clin Densitom. 2011;14:377–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi HJ, Im JA, Kim SH. Changes in bone markers after once-weekly low-dose alendronate in postmenopausal women with moderate bone loss. Maturitas. 2008;60:170–176. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li M, Zhang ZL, Liao EY, et al. Effect of low-dose alendronate treatment on bone mineral density and bone turnover markers in Chinese postmenopausal women with osteopenia and osteoporosis. Menopause. 2013;20:72–78. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31825fe2e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uchida S, Taniguchi T, Shimizu T, et al. Therapeutic effects of alendronate 35 mg once weekly and 5 mg once daily in Japanese patients with osteoporosis: a double-blind, randomized study. J Bone Miner Metab. 2005;23:382–388. doi: 10.1007/s00774-005-0616-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ro C, Cooper O. Bisphosphonate drug holiday: choosing appropriate candidates. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2013;11:45–51. doi: 10.1007/s11914-012-0129-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Black DM, Reid IR, Boonen S, et al. The effect of 3 versus 6 years of zoledronic acid treatment of osteoporosis: a randomized extension to the HORIZON-Pivotal Fracture Trial (PFT) J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:243–254. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Black DM, Schwartz AV, Ensrud KE, et al. Effects of continuing or stopping alendronate after 5 years of treatment: the Fracture Intervention Trial Long-term Extension (FLEX): a randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;296:2927–2938. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.24.2927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watts NB, Chines A, Olszynski WP, et al. Fracture risk remains reduced one year after discontinuation of risedronate. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:365–372. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0460-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schilcher J, Koeppen V, Aspenberg P, et al. Risk of atypical femoral fracture during and after bisphosphonate use. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:974–976. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1403799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schilcher J, Michaëlsson K, Aspenberg P. Bisphosphonate use and atypical fractures of the femoral shaft. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1728–1737. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watts NB, Diab DL. Long-term use of bisphosphonates in osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:1555–1565. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watts NB, Bilezikian JP, Camacho PM, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Medical Guidelines for Clinical Practice for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Endocr Pract. 2010;16(Suppl 3):1–37. doi: 10.4158/ep.16.s3.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whitaker M, Guo J, Kehoe T, et al. Bisphosphonates for osteoporosis--where do we go from here? N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2048–2051. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1202619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McClung M, Harris ST, Miller PD, et al. Bisphosphonate therapy for osteoporosis: benefits, risks, and drug holiday. Am J Med. 2013;126:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Black DM, Bauer DC, Schwartz AV, et al. Continuing bisphosphonate treatment for osteoporosis--for whom and for how long? N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2051–2053. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1202623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nancollas GH, Tang R, Phipps RJ, et al. Novel insights into actions of bisphosphonates on bone: differences in interactions with hydroxyapatite. Bone. 2006;38:617–627. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodan G, Reszka A, Golub E, et al. Bone safety of long-term bisphosphonate treatment. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20:1291–1300. doi: 10.1185/030079904125004475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strom O, Landfeldt E, Garellick G. Residual effect after oral bisphosphonate treatment and healthy adherer effects--the Swedish Adherence Register Analysis (SARA) Osteoporos Int. 2015;26:315–325. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-2900-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonnick SL, Shulman L. Monitoring osteoporosis therapy: bone mineral density, bone turnover markers, or both? Am J Med. 2006;119:S25–S31. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bauer DC, Schwartz A, Palermo L, et al. Fracture prediction after discontinuation of 4 to 5 years of alendronate therapy: the FLEX study. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1126–1134. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]