Abstract

Objective

To review the clinical data for people with diabetes mellitus with reference to their location and clinical care in a general practice in Australia.

Materials and methods

Patient data were extracted from a general practice in Western Australia. Iterative data-cleansing steps were taken. Data were grouped into Statistical Area level 1 (SA1), designated as the smallest geographical area associated with the Census of Population and Housing. The data were analysed to identify if SA1s with people aged 70 years and older, and with relatively high glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) were significantly clustered, and whether this was associated with their medical consultation rate and treatment. The analysis included Cluster and Outlier Analysis using Moran's I test.

Results

The overall median age of the population was 70 years with more males than females, 53% and 47%, respectively. Older people (>70 years) with relatively high HbA1c comprised 9.3% of all people with diabetes in the sample, and were clustered around two ‘hotspot’ locations. These 111 patients do not attend the practice more or less often than people with diabetes living elsewhere in the practice (p=0.098). There was some evidence that they were more likely to be recorded as having consulted with regard to other chronic diseases. The average number of prescribed medicines over a 13-month time period, per person in the hotspots, was 4.6 compared with 5.1 in other locations (p=0.26). Their prescribed therapy was deemed to be consistent with the management of people with diabetes in other locations with reference to the relevant diabetes guidelines.

Conclusions

Older patients with relatively high HbA1c are clustered in two locations within the practice area. Their hyperglycaemia and ongoing cardiovascular risk indicates causes other than therapeutic inertia. The causes may be related to the social determinants of health, which are influenced by geography.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, non-insulin dependent, general practice, geographic mapping, quality of health care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study extracted data from a large and established Australian general practice in a defined geographical location.

The practice maintained computerised, searchable, clinical data dating back 20 years, and the addresses of the majority of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus were reliably geocoded.

The multidisciplinary project team had data on individual patients, including their consultation history, medical history, medication history and their laboratory test results, and physiological measurements.

The conclusions are limited by the quality and completeness of the data collected by the practice.

In Australia, patients are able to consult more than one general practice, and the team could not collect data from all the practices that the patients might possibly have consulted.

Introduction

The incidence, prevalence and cost of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is increasing,1 which makes diabetes a major cause of morbidity and premature mortality in Australia.2–4 Attempts to improve outcomes for people diagnosed with diabetes were summarised in a National Service Improvement Framework for Diabetes.5

The prevalence of diabetes is highest in those over 75 years of age.6 Older people are also more likely to have other comorbid conditions.7 Often, although diabetes represents the most serious long-term risk to patients, other symptomatic conditions may dominate medical management. Therefore, comorbidity and age may be important confounding variables in the management of diabetes.8

In this study, we aimed to investigate the profile of people who were noted to have risk factors for atheromatous vascular disease in the context of diabetes mellitus. These risk factors include lipid profile, blood pressure and glucose levels. In particular, the project focused on the location of such people and their interactions with general practice, including their consultation rate, comorbidities and prescribed medication history.

Therefore, the following research questions have been identified:

Do older people with continuing risk factors associated with diabetes mellitus live in proximity to each other?

Do older people with continuing risk factors associated with diabetes mellitus receive inadequate therapy with reference to national guidelines?

Methods

Case study

It was conducted in the Peel region of Western Australia. The region is on the west coast, roughly 75 km south of the state capital, Perth. The Peel region covers an area of approximately 5648 km2 with a population of about 112 677 people, of whom around two-thirds live in the city of Mandurah.8 9 Anonymised point-level geographical data and relevant clinical information, specifically associated with patients with diabetes, were obtained from the computer data set of a large general practice clinic in this location using a customised data extraction tool.

Data collection and preparation

Data were extracted on 13 June 2014, and included all patients with diabetes, as coded by the general practice. Only data related to patients coded as having T2DM was considered for analysis. The practice had computerised data for all their patients dating back 20 years. This data set was de-identified by removing all personalised information such as names and phone numbers. A series of iterative data-cleansing steps were taken, which included data-type conversions, field completion and removal of duplicates, to ensure consistency for subsequent analysis. Clinical values were reviewed by clinicians for the exclusion of highly unlikely values. Additional patient-level observations, such as clinic visits (unique attendance) and geographical measures, including distance and time travelled to clinic were calculated. Secondary regional statistics at Statistical Area Level 1 (SA1) were obtained from the Australian Bureau of Statistics10 for information pertaining to local population demographics, a subset of which included the Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), were used in the analysis phase.

Surveillance of people with diabetes should be performed annually.11 Patients who had attended the practice within 13 months of the extraction date were deemed current. A period of 13 months was considered appropriate to allow for issues of appointment timeliness, patient commitments and return of laboratory results. Analysis of each clinical parameter was undertaken to determine if it fell within the predetermined target range based on the goals for optimum management from the ‘General practice management of Type II diabetes recommendations’.11

Geocoding

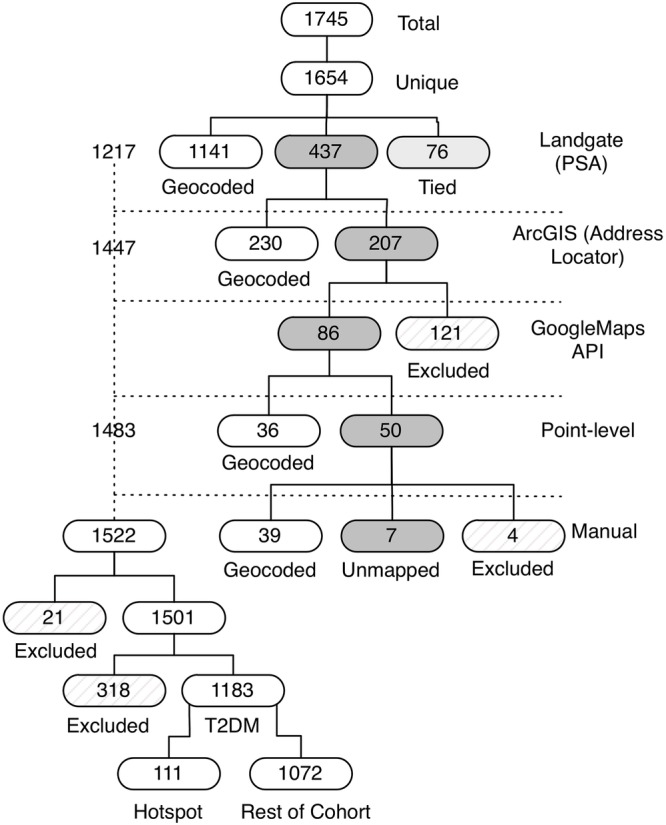

Geocoding is the process of enriching a description of a location, most typically a postal address or place name, with geographic coordinates from spatial reference data, such as street addresses or postal codes. Of the 1745 patient records obtained from the general practice, 1654 (94.8%) were identified as being unique. These unique patient entries were then geocoded, initially using the Property Street Address (point-level data set) for Western Australia, generated by Landgate—Western Australia's official registry of survey information.12 This resulted in 1141 (69%) matched (address mapped successfully), 437 (26%) unmatched (addresses that could not be successfully mapped) and 76 (5%), which were tied (more than one address per candidate). To assist the mapping rates for the unmapped data, the ArcGIS address locator was used. Just over half (230) of the 437 unmapped addresses were able to be geocoded using ArcGIS. Of the remaining 207 addresses, 121 were deleted due to incomplete addresses or addresses that were located outside of Western Australia, leaving 86 addresses that were manually assessed. All these 86 were validated using Google Maps to reassess that the localities were accurate and re-geocoded with ArcGIS. An improvement was observed through the point-level geocoding of 36 of the 86, leaving 50 addresses which were geocoded manually. This final mapping exercise resulted in 39 that were geocoded, 7 that could not be matched, and 4 that had to be excluded as they fell outside the study range. A subsequent review of the merged geocoded addresses excluded a further 21 addresses which were deemed as outliers, resulting in a total of 1522 addresses. Patients with geocoded addresses were further reviewed and another 318 were excluded because they were residing in nursing homes (to avoid spatial bias). Individuals diagnosed with T1DM, including those who were deceased, as well as excluding those patients whose last clinical visit was more than 13 months ago, resulted in a final data set, which comprised 1183 (71.5%) patients with T2DM with reliably geocoded addresses. The geocoding of patients with T2DM in this study is illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Geocoding of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Spatial analysis

Local calculations identified the extent and location of clustering and indicated where spatial clustering occurred. The output provided a representation of the statistical significance of the index values in the z-scores and p values. Sensitivity analyses were performed insofar as permutations were run in SpaceStat. The analysis included the Cluster and Outlier Analysis Anselin Local Moran's I test. Specifically, the output in this study (which was based on the median clinical values by SA1) was a layer that demonstrated statistical significance at the 0.05 confidence level areas of clusters that were of high-high values (HH), low-low values (LL), an outlier of a low value surrounded by high values (LH) and an outlier of a high value surrounded by low values (HL). As we wished to protect the identity of the localities, and therefore the patients, we did not present maps, z-scores, or p values.

Review of the medical data

The data were analysed according to the presence of cardiovascular risk factors, including hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and hyperglycaemia. Two levels of analysis were carried out.

Identification of cases where the recorded clinical parameters were beyond the upper acceptable limit as defined by the guidelines.11

Assessment of each patient's treatment regimen as recorded in the notes at the time of data extraction, to identify opportunities for dosage increases or addition of new drugs to improve clinical parameters.

The 2014–2015 guidelines for the general practice management of T2DM published jointly by the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, together with Diabetes Australia, recommend that patients with T2DM undergo annual review, which should include the measurement of blood pressure (BP), glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipid cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipid cholesterol (HDL-C), triglycerides (TG), as well as the patient's weight, to allow calculation of body mass index (BMI).11 Parameters included in this study were HbA1c (%), BP (mm Hg), TC (mmol/L), LDL-C (mmol/L) and weight (kg). Data were initially coded for currency. Parameters measured and recorded within 13 months of the extraction date were deemed current. Analysis of each parameter was undertaken to determine if it fell within the predetermined target range based on the goals for optimum management from the general practice management of T2DM recommendations,11 namely:

HbA1c target inclusion range: ≤7.5% (guideline target for HbA1c: ≤7.0%)

BP target inclusion range: ≤135/85mmHg (guideline target BP: ≤ 130/80)

TC target inclusion range: <4.0 mmol/L

LDL-C target inclusion range: <2.0 mmol/L.

Australian HbA1c measurements have been reported to have a margin of error of 0.4%, indicating that an observed level of 7.0% may be anywhere between 6.6% and 7.4%.13 Increasing the upper limit of the BP target by 5 mm Hg in both the systolic and diastolic range allows for a measurement error margin of <5%.

A clinician and researcher assessed records for all patients whose parameters fell outside the acceptable ranges for any of the following: HbA1c, BP, TC and LDL. Current medication, age and comorbidities were evaluated to determine if their current medication regimen had scope for improvement. Individuals whose BP was above guidelines, but who were on three or more antihypertensive agents, were coded separately. Individuals with an HbA1c ≥7.5 and T2DM, who had been prescribed insulin as part of their treatment regimen were excluded.

Spatial analysis

A series of analysis procedures were implemented to identify spatial patterns:

Median measures for the clinical variables were calculated at the SA1 level (eg, HbA1c, BMI, LDL, cholesterol and blood pressure);

Bivariate Moran's I test was applied14 to identify where SA1s with relatively older age and poorly controlled T2DM that were spatially clustered;

Quantifying missing data for each patient;15

Patients who resided within the identified clusters were investigated to test whether they had presented with different comorbidities and or used significantly different numbers of medications in comparison with the rest of the cohort.

Results

Descriptive results

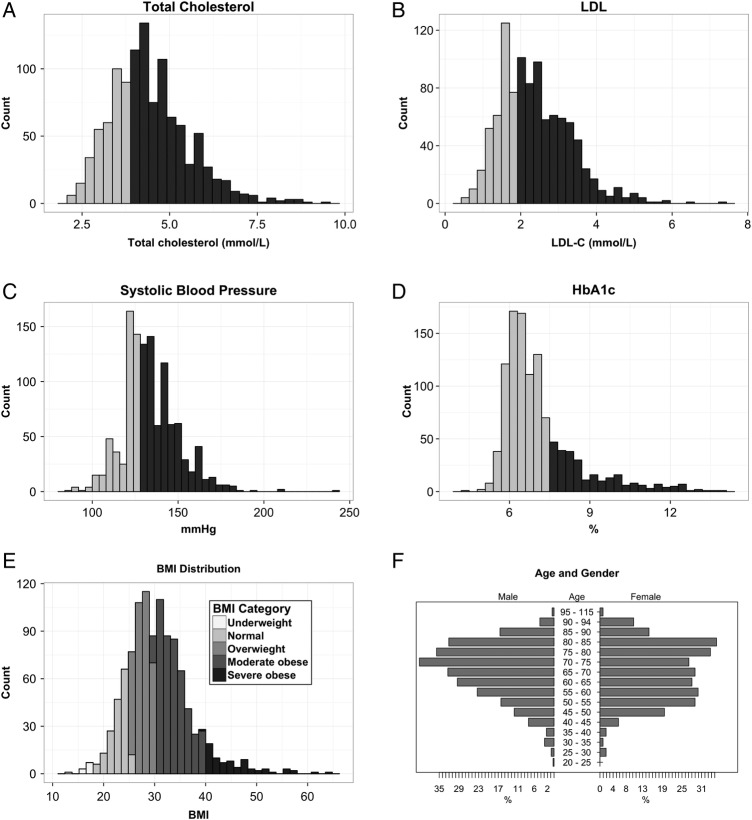

Of the available clinical measures obtained for the 1183 patients, it was found that only 4 (HbA1c, LDL, TC, systolic BP) were recorded on a consistent basis (>80% of patients), suggesting that these measures were either easier to obtain or that others were measured infrequently. The distributions for the consistently recorded measures are shown in figure 2A–F including the BMI of the study population.

Figure 2.

(A–F) Summary distributions for (A) total cholesterol; (B) low-density lipid (LDL); (C) systolic blood pressure; (D) glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c); (E) body mass index (BMI) and (F) age and gender; used to analyse patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). For plots (A–D) dark grey shading represents patients exceeding the clinical thresholds and who are in the range of concern, while the light grey shading represents patients who are maintaining healthy measures as specified by the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners.11 All incomplete records for each clinical parameter were excluded from the analysis.

Sixty-four per cent were found to have a cholesterol level higher than 4.0 mmol/L (figure 2A), while 65% of the population had increased levels of LDL above the recommended value of below 2.0 (figure 2B).

According to the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners guidelines,11 individuals with diabetes who had a systolic BP reading higher than 130 mm Hg have an increased risk of complications. Fifty-nine per cent of the population under investigation had elevated systolic readings (figure 2C).

The patients in this study area were outside the treatment target ranges on all parameters, with the exception of HbA1c (see figure 2D). The HbA1c appeared to indicate good outcomes with 68% meeting the recommended target of ≤7% as shown. Eighty-three per cent of the T2DM cohort were found to be overweight or obese (BMI≥25 kg/m2).16 Figure 2E highlights BMI categories for healthy (18–25 years), overweight (25–30 years), moderately obese (30–40 years) and severely obese (40+ years) ranges.

The median age of the population was 70 years with a slightly higher representation of males than females, 53% and 47%, respectively (figure 2F).

Spatial analysis

The HH clusters were concentrated mostly in two locations, A and B. An analysis was conducted separately on each clinical measure (HbA1c, BMI, LDL, cholesterol and BP) using both ArcGIS and SpaceStat tools. Then, the Hot Spot Analysis (Getis-Ord Gi*) statistic was performed, and the results were similar to the cluster analysis to the locations of the statistically significant hotspots. In addition, applying SpaceStat software, Bivariate Moran's I test was conducted to identify where SA1s with relatively older age and high level of HbA1c have been statistically clustered. One location was identified to be clustered and this location is one of the two HH areas identified in the previous spatial analysis procedure.

The following hypotheses were tested:

Older people (≥70 years) with higher HbA1c are clustered in specific geographical locations relative to the case study area;

Patients living in hotspot locations (a geographic region defined by those individuals statistically clustered on a selected phenotype17) are likely to have a higher proportion of ‘missing clinical data’ indicating less attention to their diabetes;

People with T2DM living in the hotspot locations compared with people living elsewhere in the practice are likely to attend the practice less often, take fewer medications, have more chronic illness, and are less likely to be managed as per the guidelines.

Hypothesis 1

Older people with relatively high HbA1c (≥7.5%) comprised 9.3% of all people with T2DM in the sample, and were clustered around two locations, locations A and B. Location A is relatively deprived, corresponding with a low SEIFA Index.18 This was below the Western Australian average of 1021.86 score. Location A has a median age of 41 years with 22.1% of residents over the age of 65 years. The median age of the patients with T2DM living in this location in our study was 69 years. Location B, however, was a relatively affluent area with 34% of the population over the age of 65 years and a median age of 54 years. Patients with T2DM from this location had a median age of 72 years. To protect the privacy of patients, these locations are not displayed in a graph.

Hypothesis 2

A comparison between the percentage of patient records within the identified hotspot locations (locations A and B) with missing clinical data, and those in the remainder of the practice region with missing data, was conducted. Table 1 indicates that there were no significant differences on any measure between hotspot locations and the rest of the cohort.

Table 1.

Missing clinical measurement summary for all T2DM (1183) within the 13-month study period from May 2013 to June 2014 (p<0.05 is significant)

| Missing measurements |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical measure | Hotspot locations (n=111) | Rest of cohort (n=1072) | |

| Count | Count | p Value | |

| HbA1c | 5 (4.5) | 84 (7.8) | 0.21 |

| Cholesterol | 6 (5.4) | 85 (7.9) | 0.34 |

| LDL | 12 (10.8) | 171 (16.0) | 0.15 |

| Systolic | 0 (0) | 18 (1.7) | 0.17 |

| Diastolic | 0 (0) | 18 (1.7) | 0.17 |

| HDL | 10 (9.0) | 142 (13.2) | 0.20 |

| Height | 8 (7.2) | 97 (9.0) | 0.52 |

| Weight | 2 (1.8) | 65 (6.1) | 0.06 |

| Waist circumference | 64 (57.7) | 655 (61.1) | 0.48 |

| Triglycerides | 7 (6.3) | 96 (9.0) | 0.35 |

HbA1c, glycosylated haemoglobin; HDL, high-density lipid; LDL, low-density lipid; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Hypothesis 3

Attendance

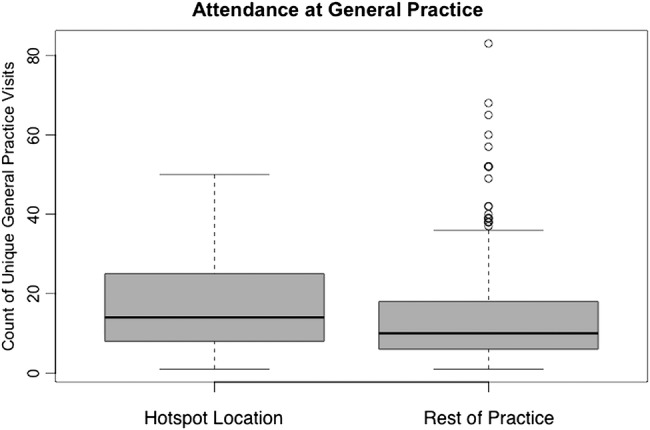

Our data suggest that people with T2DM in the hotspot locations do not attend the practice more or less often than people with T2DM living elsewhere in the practice (p=0.1) (figure 3).

Figure 3.

A box plot comparison of the number of unique doctor visits between the hotspot locations with the rest of the practice population.

Chronic illness

There were only two chronic conditions that people with T2DM living in hotspot locations were more likely to have consulted their doctor about, as shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Percentage of major conditions identified in both hotspot cluster regions compared with the surrounding/other regions

| Chronic condition | Hotspot location (n=111 (%)) | Rest of cohort (n=1072 (%)) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angina | 5 (4.5) | 29 (2.7) | 0.56 |

| Asthma | 24 (21.6) | 155 (14.5) | 0.39 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 9 (8.1) | 99 (9.2) | 0.27 |

| Back pain | 26 (23.4) | 133 (12.4) | 0.04* |

| Cancer | 10 (9.0) | 120 (11.2) | 0.14 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 6 (5.4) | 57 (5.3) | 0.61 |

| Chronic pain | 2 (1.8) | 21 (2.0) | 0.67 |

| Dementia | 2 (1.8) | 17 (1.6) | 0.89 |

| Depression | 25 (22.5) | 188 (17.5) | 0.92 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 10 (9.0) | 143 (13.3) | 0.04* |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 9 (8.1) | 79 (7.4) | 0.69 |

| Myocardial infarction | 3 (2.7) | 57 (5.3) | 0.10 |

| Osteoarthritis | 34 (30.6) | 270 (25.2) | 0.82 |

*p Value with a significance of ≤0.05.

Use of medications

In the hotspot locations, there was an average 4.6 scripts (number of prescribed medicines as recorded on the patient records) per person over the 13-month study period, compared with 5.1 in other locations (p=0.26), indicating no significant difference.

Control of diabetes

The clinical parameters that were appropriately managed were compared in the hotspot location and the rest of the cohort. As shown in table 3 all clinical parameters other than triglycerides were considered equally well managed in all locations. In some cases even though the most recent test results were not within the target range the prescription record for the patient suggested no scope for improving the prescribed treatment.

Table 3.

Clinical measures managed per guidelines between the identified hotspot locations and the surrounding areas

| Clinical measure | Within guidelines |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hotspot location | Rest of the sample | ||

| n=111 Count (%) | n=1072 Count (%) | p Value | |

| HbA1c | 67 (60.4) | 561 (52.3) | 0.11 |

| Cholesterol | 30 (27.0) | 261 (24.3) | 0.53 |

| LDL | 27 (24.3) | 225 (21.9) | 0.41 |

| Systolic | 49 (44.1) | 463 (45.1) | 0.85 |

| Diastolic | 65 (58.6) | 644 (62.7) | 0.76 |

| HDL | 54 (48.6) | 453 (44.1) | 0.70 |

| Triglycerides | 28 (25.2) | 416 (40.5) | 0.005* |

| BMI | 19 (17.1) | 163 (15.9) | 0.60 |

*p Value with a significance of ≤0.05.

BMI, body mass index; HbA1c, glycosylated haemoglobin; HDL, high-density lipid; LDL, low-density lipid.

Discussion

The key finding of this study was that a significant proportion of people with a relatively high HbA1c served by one general practice were clustered in and around two specific locations. These patients were managed similarly with reference to the guidelines. Likewise, attendance rate at the practice was equivalent to that of other patients with T2DM served by the practice. There was not a greater proportion of missing patient data in these hotspot locations, suggesting that there was neither greater nor lesser surveillance of these patients. The locations identified were, in one case, associated with socioeconomic deprivation, and in the other a high proportion of older residents. Patients in these locations were not prescribed more medications, but had a higher prevalence of some comorbidities.

Three possible explanations exist for the above findings. The first is that, as has been reported previously, other comorbidity or psychosocial factors associated with age distract from the focus on diabetes in the doctor–patient consultation.7 In the same vein, patients may be prescribed medicines and given advice, but that does not mean they are following that advice. Second, these patients might be attending other practices for advice about their diabetes. In regard to the first possibility, we did find some evidence of greater comorbidity in this group of patients. With reference to the latter possibility, national data from Australia suggests that more than 90% of older people will attend only one general practice.19 This is therefore much less likely. Third, it is also possible that we are observing that people with similar risk factors, age, social and cultural backgrounds chose to live in proximity.

If geographical patterns are confirmed in other Australian practices, this may be evidence of the impact of geography on outcomes for non-communicable chronic illness. In a systematic review of the literature published in 2014, the authors reported that only a few studies investigated the impact of ‘Neighbourhood and Built Environment’ on T2DM outcomes.20 Seligman21 reported that people with diabetes who were not able to afford safe and nutritious food were more likely to have poor glycaemic control in parts of the USA.21 Additionally, a lower neighbourhood socioeconomic status was significantly associated with poorer physical and mental health.22 23 Though many authors have suggested that neighbourhood context plays a role in diabetes outcomes, this topic needs further research to fully understand the impact. One important finding from our data is that age was a significant factor in the observed geographical patterns. Therefore, elements of the environment that preclude healthier choices, especially by older people who may be limited by poor mobility, may be relevant.24

Finally, we reflect on Tudor Hart's inverse care law.25 Hart posited that people with the greatest need are least well served. In this study, we present data that suggest that patients in the hotspot locations were accessing their general practice as much as patients in other locations, and yet appear to have poorer results. It is possible that these patients had greater needs and perhaps should be attending more often. Alternatively, it is also possible that the practice is unable to reduce cardiovascular risk related to diabetes because of other considerations to do with neighbourhood, built environment and competing priorities for the patient. Therefore, it is not that health services are less available, but that other health, social or environmental factors may limit the impact of those services.

Strengths and limitations

We acknowledge several limitations of this study. The project was conducted with data from only one, albeit large practice in Western Australia. The patterns observed are likely to be influenced by the local organisation of the healthcare services. Patients are able to consult practitioners at multiple practices in this setting and we were not able to collect data from those practices. The conclusions are limited by the quality and completeness of the data collected by the practice. Despite these limitations, the study offers a new perspective on the healthcare of patients with diabetes. Thus, we generate a hypothesis that such patterns may inspire new geographically driven approaches to the management of T2DM.26 27

In addition, we acknowledged the significance of having access to point-level data in this study; this aligns with the findings of Bagheri23 that highlighted limitations with only using SA1 (aggregated) data. Access to point-level data allowed us to add contextual-based evidence, such as medication prescription, GP attendance and specific individual clinical parameters, while maintaining privacy of data.

Conclusions

Older people with T2DM and higher cardiovascular risk have been shown to be clustered in defined geographical locations. If such geographical patterns for chronic diseases such as diabetes are confirmed in other places, the data offer the prospect of more geographically targeted interventions to reduce health risks related to diabetes. We hope that future studies will adopt spatial approaches to analyse patient records and will lead to further development of spatial techniques in analysing patient data. Studies in this domain are important not only in terms of their health applications and spatial techniques, but also for targeting scarce resources by adding a spatial lens.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the advice and input of the advisory committee, including and especially Dr Phillip Collier, Peter Woodgate, Dr Georgina Pagey, Professor William Hart, Mr Ian Peters and the staff and doctors at the Mandurah Medical Centre.

Footnotes

Contributors: MJ, OG, RV and NM conceived the project and oversaw the design of the study. RV and OG conducted statistical analyses and analysed the data. OG coordinated the study. OG and RV oversaw the collection of data and implemented the study. All authors interpreted the data and results, prepared the report and the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Funding: The work has been supported by the Cooperative Research Centre for Spatial Information whose activities are funded by the Business Cooperative Research Centres Programme. Also partly funded by the Department of Medical Education, Curtin University.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Curtin Human Research Ethics Committee (03-04-2018).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Zhang P, Zhang X, Brown J et al. Global healthcare expenditure on diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010;87:293–301. 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.01.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Diabetes Canberra 2013 (cited 5 September 2014). http://www.aihw.gov.au/diabetes/

- 3.Tigbe WW, Briggs AH, Lean ME. A patient-centred approach to estimate total annual healthcare cost by body mass index in the UK Counterweight programme. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013;37:1135–9. 10.1038/ijo.2012.186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee CM, Colagiuri R, Magliano DJ et al. The cost of diabetes in adults in Australia. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2013;99:385–90. 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Australian Government—The Department of Health. National service improvement framework for diabetes 2005 (cited 1 July 2015). http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/pq-ncds-diabetes

- 6.Dunstan DW, Zimmet PZ, Welborn TA et al. The rising prevalence of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance: the Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle Study. Diabetes Care 2002;25:829–34. 10.2337/diacare.25.5.829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piette JD, Kerr EA. The impact of comorbid chronic conditions on diabetes care. Diabetes Care 2006;29:725–31. 10.2337/diacare.29.03.06.dc05-2078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Government of Western Australia PEEL Development Commission. Quick Peel Statistics 2014 (cited 23 September 2014). http://peel.wa.gov.au/our-region/peel-statistics/

- 9.Government of Western Australia Peel Development Commission. Peel Profile September 2012 (cited 5 October 2015). http://peel.wa.gov.au/wpcontent/uploads/PeelProfileSeptember2012.pdf

- 10.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census of Population and Housing: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2011. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; (updated 2011 cited July 2015). http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/2033.0.55.001main+features100132011 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. General practice management of type 2 diabetes 2014–2015. RACGP, 2014. (cited 11 September 2014). http://www.racgp.org.au/your-practice/guidelines/diabetes/8-managing-glycaemia/84-insulin/ [Google Scholar]

- 12.Government of Western Australia. Landgate. CSD Street Addresses 2014 (cited 1 July 2014). http://www0.landgate.wa.gov.au

- 13.National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program. Factors that Interfere with HbA1c Test Results (cited 5 October 2015). http://www.ngsp.org/factors.asp

- 14.Fotheringham AS, Brunsdon C, Charlton M. Quantitative geography: perspectives on spatial data. Sage, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott L, Getis A. Spatial statistics. In: Kemp K, ed. Encyclopedia of geographic information science. Sage Publications, 2008:439. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heart Foundation of Australia. BMI calculator 2014 (cited 23 September 2014). http://www.heartfoundation.org.au/healthy-eating/Pages/bmi-calculator.aspx

- 17.Morais C. What is the difference between a heat map and a hot spot map? 2014 (cited 15 May 2015). http://www.gislounge.com/difference-heat-map-hot-spot-map/

- 18.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census of Population and Housing: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2011. (cited 1 July 2015). http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/bySubject/2033.0.55.001~2011~MainFeatures~FAQs-SEIFA2011~9 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menzies Centre for Health Policy. The Menzies-Nous Australian Health Survey. 2012 23 October 2012. Report (cited 5 October 2015). http://www.nousgroup.com/images/news_attachments/Menzies-Nous_Australian_Health_Survey_Report_2012.pdf

- 20.Walker RJ, Smalls BL, Campbell JA et al. Impact of social determinants of health on outcomes for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Endocrine 2014;47:29–48. 10.1007/s12020-014-0195-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seligman HK, Jacobs EA, López A et al. Food insecurity and glycemic control among low-income patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012;35:233–8. 10.2337/dc11-1627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gary-Webb TL, Baptiste-Roberts K, Pham L et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic status, depression, and health status in the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) study. BMC Public Health 2011;11:349 10.1186/1471-2458-11-349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bagheri N, McRae I, Konings P et al. Undiagnosed diabetes from cross-sectional GP practice data: an approach to identify communities with high likelihood of undiagnosed diabetes. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005305 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balfour JL, Kaplan GA. Neighborhood environment and loss of physical function in older adults: evidence from the Alameda County Study. Am J Epidemiol 2002;155:507–15. 10.1093/aje/155.6.507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tudor Hart J. The inverse care law. Lancet 1971;297:405–12. 10.1016/S0140-6736(71)92410-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caughey GE, Vitry AI, Gilbert AL et al. Prevalence of comorbidity of chronic diseases in Australia. BMC Public Health 2008;8:221 10.1186/1471-2458-8-221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duckworth W, Abraira C, Moritz T et al. Glucose control and vascular complications in veterans with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2009;360:129–39. 10.1056/NEJMoa0808431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]