Abstract

Purpose

The main objective of the Bushehr Elderly Health Programme, in its first phase, is to investigate the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and their association with major adverse cardiovascular events.

Participants

Between March 2013 and October 2014, a total of 3000 men and women aged ≥60 years, residing in Bushehr, Iran, participated in this prospective cohort study (participation rate=90.2%).

Findings to date

Baseline data on risk factors, including demographic and socioeconomic status, smoking and medical history, were collected through a modified WHO MONICA questionnaire. Vital signs and anthropometric measures, including systolic and diastolic blood pressure, weight, height, and waist and hip circumference, were also measured. 12-lead electrocardiography and echocardiography were conducted on all participants, and total of 10 cc venous blood was taken, and sera was separated and stored at –80°C for possible future use. Preliminary data analyses showed a noticeably higher prevalence of risk factors among older women compared to that in men.

Future plans

Risk factor assessments will be repeated every 5 years, and the participants will be followed during the study to measure the occurrence of major adverse cardiac events. Moreover, the second phase, which includes investigation of bone health and cognition in the elderly, was started in September 2015. Data are available at the Persian Gulf Biomedical Research Institute, Bushehr University of Medical Sciences, Bushehr, Iran, for any collaboration.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first large sample prospective cohort study in Iran focusing on cardiovascular risk factors in the elderly as a growing population.

The long-term follow-up in this study will allow for the assessment of many relevant outcomes.

The participation rate in this study was high; however, outcome ascertainment may be incomplete because of incomplete death and MACE registries.

Introduction

The world's population is ageing rapidly. The proportion of those over the age of 60 years will double, from about 11% to 22%, between 2000 and 2050. The absolute number of people aged 60 years and over is expected to increase from 605 million to 2 billion over the same period.1 According to the latest Iranian Census Data, about 8.2% of the population was over 60 years of age in 2011.2 By the year 2020, the elderly population (over 60 years of age) is estimated to reach 10%.

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is one of the leading causes of disease burden in developing countries. In other words, three-fourths of global deaths due to CHD occurred in low-income and middle-income countries.3 In the year 2003, there were 21 572 Disability Adjusted Lost Years (DALYs) due to all diseases and injuries per 100 000 Iranian people of all ages and both sexes. From this total number of DALYs, 58% were due to non-communicable diseases; ischaemic heart disease was the fourth cause of DALYs in males and the first cause of DALYs in females.4

There is a need for effective public health action on cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention, especially in low-income and middle-income countries, and for assessments of the cost-effectiveness of feasible interventions.5 In addition, there is a need to try to balance the fight against the existing burden of infectious diseases with the growing epidemic of chronic diseases such as heart disease and diabetes.6 The high costs of direct medical care and the indirect costs of CVD, according to the American Heart Association, were approaching $450 billion annually in 2010 and were projected to rise to over $1 trillion annually by 2030.7 Prevention of premature deaths due to non-communicable diseases and the reduction of related healthcare costs should be the main goals of health policy. Improving the detection and treatment of non-communicable diseases, and preventing complications and catastrophic events from occurring, should be the major goals of clinical medicine.8 Trends in CVD risk factors and blood glucose will result in substantial CVD burden in developing countries and economies in transition in the near future. Periodic and consistent monitoring of trends and the effects of these risk factors on disease burden is needed for prioritising prevention programmes.9

In recent decades, cohort studies have played a major role in investigating the incidence and causes of common health outcomes. As major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) are quite common in old age, there are many cohort studies investigating these outcomes. A vast majority of these cohort studies are being conducted in developed countries.10–20 However, the number of such prospective studies in the developing world is also rising.21–25 In Iran, there are a few large prospective studies being conducted in various fields. Golestan's cohort study, a prospective study of oesophageal cancer in northern Iran,26 the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study (TLGS)27 and the Shahrood Eye Cohort Study (ShECS),28 are among these studies. The Amirkola Health and Ageing Project (AHAP) is the only large sample prospective cohort study in Iran, specifically aimed at investigating falling, bone fragility and fractures, cognitive impairment and dementia, poor mobility and functional dependence in the elderly.29

This paper describes the rationale for, design and preliminary results of the Bushehr Elderly Health (BEH) Programme, a population-based prospective cohort study conducted in Bushehr, a southern province of Iran. The main objective of this study, in its first phase, is to investigate the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and their association to MACE.

Cohort description

The target population of this prospective cohort study was all men and women aged 60 years and over residing in the city of Bushehr. Based on the information available from the Bushehr District Health Centre, this population was estimated to be around 10 000. Box 1 shows eligibility criteria for participation in the study.

Box 1. List of inclusion and exclusion criteria of participants.

Inclusion criteria

Age more than or equal to 60 years

Both sexes

Residency in Bushehr port since at least 1 year prior to the recruitment

No plan to leave Bushehr for the following 2 years after the recruitment

Adequate physical and mental ability to participate in the evaluation programme

Signing of written informed consent

Exclusion criteria

No residence in Bushehr

Unwilling to participate in the study

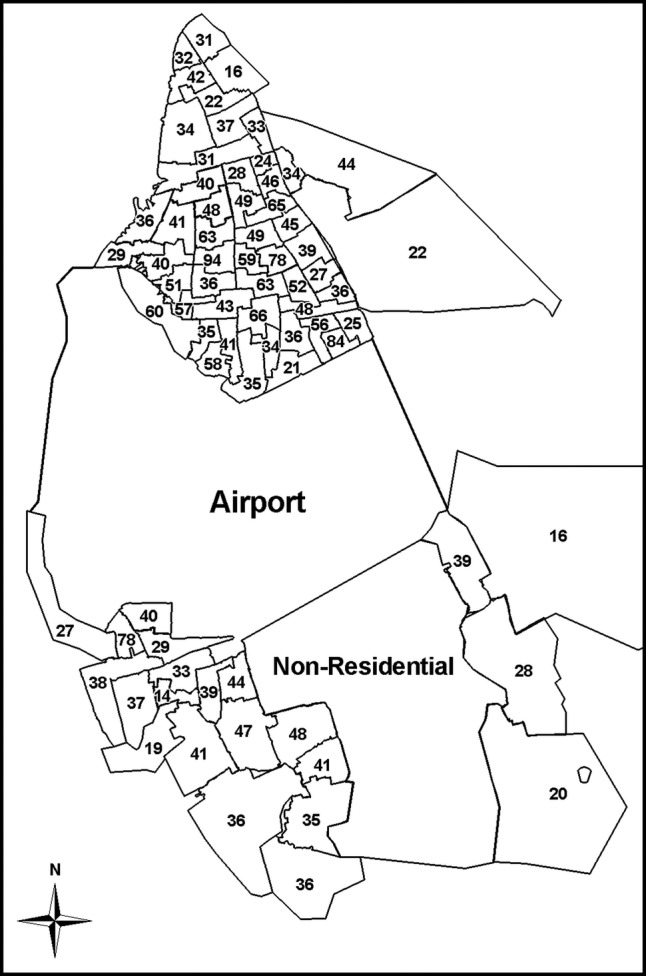

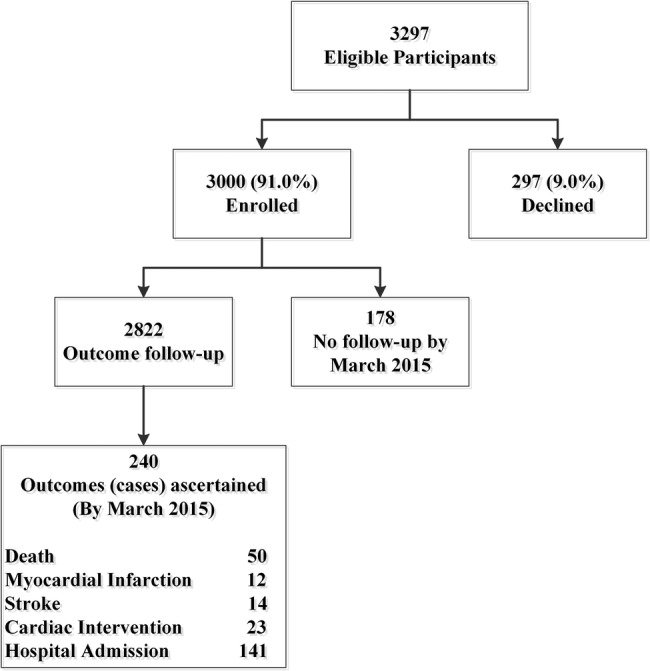

The participants in the BEH Programme were selected through a multistage, stratified cluster random sampling method. Based on the classifications made by the municipality, as shown in figure 1, we stratified Bushehr to 75 strata. Numbers were assigned to the blocks (as clusters) of each stratum and then randomly sorted. We invited all eligible older people residing in each block selected to participate and then moved to the next block, repeating the invitation process, until we gained the sample required for that stratum. Sample sizes for strata were determined proportional to the number of households residing in each stratum. As shown in figure 2, between March 2013 and October 2014, from among 3297 older people aged 60 years and over who were invited, a total of 3000 participated in this study (participation rate: 91.0%). Non-respondents were found among all strata, and there was no obvious pattern indicating selection bias. Baseline characteristics of participants are shown in table 1.

Figure 1.

Map of Bushehr and distribution of participants in the strata.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of enrolments.

Table 1.

Baseline sociodemographic characteristics of participants in Bushehr Elderly Health Programme

| Characteristics (N (%)) | Men (1455 (48.5)) | Women (1545 (51.5)) |

|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | ||

| ≤64 | 616 (42.3) | 674 (43.6) |

| 65–69 | 317 (21.8) | 378 (24.5) |

| 70–74 | 230 (15.8) | 200 (12.9) |

| 75–79 | 166 (11.4) | 181 (11.7) |

| ≥80 | 126 (8.7) | 112 (7.2) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 5 (0.3) | 20 (1.3) |

| Married | 1378 (94.7) | 884 (57.2 |

| Widowed | 68 (4.7) | 619 (40.1) |

| Divorced | 4 (0.3) | 22 (1.4) |

| Current occupation | ||

| Employed | 133 (9.1) | 23 (1.5) |

| Retired | 1195 (82.1) | 126 (8.2) |

| Unemployed* | 127 (8.7) | 1396 (90.4) |

| Education | ||

| No education | 315 (21.6) | 777 (50.3) |

| Primary school | 400 (27.5) | 459 (29.7) |

| Secondary School | 276 (19.0) | 151 (9.8) |

| High school | 287 (19.7) | 125 (8.1) |

| University | 177 (12.2) | 33 (2.1) |

*Homemaker for female.

The main follow-up assessments of risk factors will be carried out every 5 years for three consecutive periods (a total of 15 years of follow-up), in which all assessments will be repeated with comparable methods and modalities.

In addition, interim assessments will be made to ascertain outcomes and risk factor changes.

All participants will be contacted by a trained nurse once annually, and a checklist will be completed to check if any outcome of interest (major adverse cardiac events) has occurred during the 12 months prior to the assessment. A form has also been distributed to the participants to self-report as soon as possible after the occurrence of any of the targeted outcomes. Focal points in the two main hospitals in Bushehr (Shohadaye-Khalij-e-Fars and Salman-e-Farsi hospitals) are responsible for monthly checking of the hospital information system (HIS) and reporting admissions. If any outcome is reported, a general physician will review the inpatient/outpatient medical records and documents, and detailed information will be entered into the special outcome forms. Our database will be cross-linked with the death registry system database, available via the public health system. The death registry system receives information from hospitals, forensic medicine departments, cemeteries and vital events records offices, and duplicate records are deleted. The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 10, WHO online version, is used to classify causes of death. A person's national identification number is used as a unique identifier to cross-link databases. In the case of a death report but no reliable death certificate, a verbal autopsy will be performed to determine cause of death. Box 2 presents list of outcomes ascertained in the present study.

Box 2. List of outcomes, Bushehr Elderly Health Programme study.

Death

Myocardial infarction

Stroke

Cardiac interventions

Hospital admission

Baseline examination

A modified WHO MONICA questionnaire30 translated into Persian was used as the core questionnaire to gather baseline information on demographic and socioeconomic variables and risk factors. Table 2 presents the components of the core questionnaire.

Table 2.

Section and topics of the Core Questionnaire in the Bushehr Elderly Health Programme study

| Type of data | Components |

|---|---|

| Demographic | ▸ Personal information (name, nickname, surname) ▸ National identification number ▸ Age and sex ▸ Marital status ▸ Contact information |

| Socioeconomic | ▸ Employment status ▸ Education level ▸ Insurance ▸ Family income ▸ Family assets ▸ Residence status |

| Cardiovascular risk factors and medical history | ▸ Smoking status and history ▸ Physical activity ▸ Menstrual and menopause history |

| ▸ Blood pressure history ▸ Diabetes history ▸ Lipid profile history ▸ Ischaemia and myocardial infarction history ▸ Weakness, impaired sensation and stroke history ▸ Rose and claudication history ▸ Heart failure history |

|

| Drug history | ▸ Administered by physician ▸ Over the counter drugs ▸ Supplements |

Phlebotomy and laboratory analyses

Participants were asked to provide a venous blood sample for laboratory tests. A total of 10 cc of whole blood was taken by a trained nurse after 8–12 h of fasting. Table 3 presents laboratory tests performed at baseline and their methods of measurement. Sera were also separated and stored at –80°C for possible future use.

Table 3.

Baseline physical examinations and laboratory tests, Bushehr Elderly Health Programme study

| Item | Method of measurement | |

|---|---|---|

| Physical examination | ||

| Arterial blood pressure | Manually by standard mercury sphygmomanometer in sitting position | |

| Weight in kg | Stadiometer; heavy outer garments will be removed | |

| Height in cm | Stadiometer; shoes will be removed | |

| Waist circumference in cm | At the midway level between the costal margins and the iliac crests | |

| Hip circumference in cm | At the level of the greater trochanters | |

| Laboratory tests | ||

| CBC | Automated haematology analyser | |

| Fasting blood sugar | enzymatic (glucose oxidase) colourimetric method using a commercial kit (Pars Azmun Inc, Tehran, Iran) | |

| Lipid profile (total cholesterol, LDL-C, HDL-C, triglyceride) | Serum total cholesterol and HDL cholesterol will be measured using a cholesterol oxidase phenol aminoantipyrine and triglycerides using a glycerol-3-phosphate oxidase phenol aminoantipyrine enzymatic method. Serum LDL cholesterol will be calculated using the Friedwald formula; LDL cholesterol will not be calculated when triglycerides concentration is >400 mg/dL | |

| Procedures | ||

| Electrocardiography | 12-lead, by a trained nurse | |

| Echocardiography | Using M-Turbo Ultrasound System, Manufactured by SonoSite, Inc, by a cardiologist | |

CBC, complete blood count; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

Clinical assessment

A comprehensive physical examination, including vital signs, weight and height measurements, and waist and hip circumference, were taken at baseline. Twelve-lead electrocardiography, performed by a trained nurse, and echocardiography, carried out by a cardiologist, were conducted for all participants (see table 3).

Findings to date

Baseline data are being analysed, and preliminary findings are presented in table 4.31 The prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors was remarkably higher among older women compared to that in men. Smoking behaviour was different among older men and women. Older women did not smoke cigarettes as often as men; however, the prevalence of hookah smoking was higher in women. One-third of older women were obese, which was two times more than the prevalence of obesity among men. Metabolic syndrome was also about two times more prevalent among older women.

Table 4.

Frequency and age-adjusted proportions of risk factors in participants of the Bushehr Elderly Health Programme

| Risk factor (N (%)) | Men (1455 (48.5)) | Women (1545 (51.5)) |

|---|---|---|

| Smoking | ||

| Hookah | ||

| Non-smoker | 1143 (78.8) | 951 (61.4) |

| Current smoker | 110 (7.5) | 267 (17.2) |

| Intermittent smoker | 4 (0.3) | 7 (0.5) |

| Former smoker | 198 (13.4) | 320 (20.9) |

| Cigarette | ||

| Non-smoker | 1023 (70.3) | 1522 (98.5) |

| Current smoker | 198 (13.7) | 14 (0.9) |

| Intermittent smoker | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Former smoker | 233 (16.0) | 9 (0.6) |

| Hypertension | 820 (56.1) | 1054 (68.4) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 390 (27.0) | 506 (32.6) |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 886 (61.0) | 1034 (66.9) |

| BMI* | ||

| <25 | 615 (42.6) | 414 (27.8) |

| 25–29.9 | 612 (42.7) | 591 (39.0) |

| ≥30 | 211 (14.7) | 511 (33.2) |

| Metabolic syndrome† | 403 (28.5) | 826 (53.3) |

*Forty-six missing.

†Based on the NCEP ATP III.

‡Percentages are age-adjusted.

BMI, body mass index.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first large sample prospective cohort study in Iran focusing on cardiovascular risk factors in the elderly as a growing population. The long-term follow-up in this study will allow for the assessment of many relevant outcomes. The participation rate in this study was high; however, outcome ascertainment may be incomplete because of incomplete death and MACE registries.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the staff of both research centres at BPUMS and TUMS for their commitment to the study's protocol and objectives. They are also indebted to all participants who accepted the invitation and patiently underwent exhausting measurements and examinations.

Footnotes

Contributors: AO drafted the manuscript, participated in study design and conduction, performed data analysis and interpretation. IN conceived the study, helped draft the manuscript, participated in the study design and conduction, and data analysis and interpretation. BL participated in the study design and conduction and reviewed the manuscript. RH helped draft the manuscript, participated in the study design and conduction, and data analysis and interpretation. HD, KV, NM, GH, AR and MH participated in the study design and reviewed the manuscript. MP, AA, RN, HS and MB participated in the study design and data collection, and reviewed the manuscript. MR, GS, FS, AN and RT participated in questionnaire development, study design and staff training, and reviewed the manuscript. HAM, MRA, SF, SD and DM participated in data collection and reviewed the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Funding: The Persian Gulf Biomedical Sciences Research Institute affiliated with Bushehr (Port) University of Medical Sciences (BPUMS) and the Endocrinology and Metabolism Research Institute, affiliated with Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS), jointly provided funding for this research project.

Ethics approval: This study is being conducted in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki and in accordance with Iranian national guidelines for ethics in research. The protocol of the study was approved by the regional research ethics committee of Bushehr University of Medical Sciences on 23 September 2013, Reference number: B-91–14-2. All participants were asked to sign a written informed consent, which was approved by the research ethics committee. The participants are able to withdraw from the study at any time without any explanation. Data collected are stored in a re-identifiable form by national ID code. The results will be presented at national and international meetings and published in a peer-reviewed journal. We aim to translate the key findings to an easily understandable format for local residents and to present them through local media. Relevant findings will also be presented as policy briefs to national and local health policy makers.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: A large amount of data have been collected. Access to the data is available for interested researchers from corresponding author IN (inabipour@gmail.com) or from AO (a.ostovar@bpums.ac.ir).

References

- 1.Interesting facts about ageing. Secondary Interesting facts about ageing 2012. http://www.who.int/ageing/about/facts/en/index.html

- 2.Selected Findings of National Population and Housing Census, 2011. In: Public relations and International Cooperation (ed). Tehran: Statistical Center of Iran; 2012, p 27.

- 3.Gaziano TA, Bitton A, Anand S et al. Growing epidemic of coronary heart disease in low- and middle-income countries. Curr Probl Cardiol 2010;35:72–115. 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naghavi M, Abolhassani F, Pourmalek F et al. The burden of disease and injury in Iran 2003. Popul Health Metr 2009;7:9 10.1186/1478-7954-7-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Labarthe DR, Dunbar SB. Global cardiovascular health promotion and disease prevention: 2011 and beyond. Circulation 2012;125:2667–76. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.087726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shetty P. Grey matter: ageing in developing countries. Lancet 2012;379:1285–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60541-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weintraub WS, Daniels SR, Burke LE et al. Value of primordial and primary prevention for cardiovascular disease: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011;124:967–90. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182285a81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunter DJ, Reddy KS. Noncommunicable diseases. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1336–43. 10.1056/NEJMra1109345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh GM, Danaei G, Farzadfar F et al. The age-specific quantitative effects of metabolic risk factors on cardiovascular diseases and diabetes: a pooled analysis. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e65174 10.1371/journal.pone.0065174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schoeni-Affolter F, Ledergerber B, Rickenbach M et al. Cohort profile: the Swiss HIV Cohort study. Int J Epidemiol 2010;39:1179–89. 10.1093/ije/dyp321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hofman A, van Duijn CM, Franco OH et al. The Rotterdam Study: 2012 objectives and design update. Eur J Epidemiol 2011;26:657–86. 10.1007/s10654-011-9610-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell GF, Hwang SJ, Vasan RS et al. Arterial stiffness and cardiovascular events: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2010;121:505–11. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.886655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christiansen CB, Olesen JB, Gislason G et al. Cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular hospital admissions associated with atrial fibrillation: a Danish nationwide, retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2013;3:pii: e001800 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Welmer AK, Angleman S, Rydwik E et al. Association of cardiovascular burden with mobility limitation among elderly people: a population-based study. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e65815 10.1371/journal.pone.0065815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vu TH, Stamler J, Liu K et al. Prospective relationship of low cardiovascular risk factor profile at younger ages to ankle-brachial index: 39-year follow-up—the Chicago Healthy Aging Study. J Am Heart Assoc 2012;1:e001545 10.1161/JAHA.112.001545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marmot M, Brunner E. Cohort Profile: the Whitehall II study. Int J Epidemiol 2005;34:251–6. 10.1093/ije/dyh372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lahelma E, Aittomäki A, Laaksonen M et al. Cohort profile: the Helsinki Health Study. Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:722–30. 10.1093/ije/dys039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cumming RG, Handelsman D, Seibel MJ et al. Cohort Profile: the Concord Health and Ageing in Men Project (CHAMP). Int J Epidemiol 2009;38:374–8. 10.1093/ije/dyn071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magnus P, Irgens LM, Haug K et al. Cohort profile: the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa). Int J Epidemiol 2006;35:1146–50. 10.1093/ije/dyl170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osler M, Lund R, Kriegbaum M et al. Cohort profile: the Metropolit 1953 Danish male birth cohort. Int J Epidemiol 2006;35:541–5. 10.1093/ije/dyi300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otgontuya D, Oum S, Buckley BS et al. Assessment of total cardiovascular risk using WHO/ISH risk prediction charts in three low and middle income countries in Asia. BMC Public Health 2013;13:539 10.1186/1471-2458-13-539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kok VC, Horng JT, Lin HL et al. Gout and subsequent increased risk of cardiovascular mortality in non-diabetics aged 50 and above: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2012;12:108 10.1186/1471-2261-12-108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Victora CG, Barros FC. Cohort profile: the 1982 Pelotas (Brazil) birth cohort study. Int J Epidemiol 2006;35:237–42. 10.1093/ije/dyi290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woodward M, Barzi F, Martiniuk A et al. Cohort profile: the Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration. Int J Epidemiol 2006;35:1412–16. 10.1093/ije/dyl222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang C, Thomas GN, Lam TH et al. Cohort profile: The Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study, a Guangzhou-Hong Kong-Birmingham collaboration. Int J Epidemiol 2006;35:844–52. 10.1093/ije/dyl131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pourshams A, Khademi H, Malekshah AF et al. Cohort Profile: the Golestan Cohort Study--a prospective study of oesophageal cancer in northern Iran. Int J Epidemiol 2010;39:52–9. 10.1093/ije/dyp161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Azizi F, Rahmani M, Emami H et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in an Iranian urban population: Tehran lipid and glucose study (phase 1). Soz Praventivmed 2002;47:408–26. 10.1007/s000380200008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fotouhi A, Hashemi H, Shariati M et al. Cohort profile: Shahroud Eye Cohort Study. Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:1300–8. 10.1093/ije/dys161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hosseini SR, Cumming RG, Kheirkhah F et al. Cohort profile: the Amirkola Health and Ageing Project (AHAP). Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:1393–400. 10.1093/ije/dyt089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bothig S. WHO MONICA Project: objectives and design. Int J Epidemiol 1989;18(3 Suppl 1):S29–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalton G. Standardization: A Technique to Control for Extraneous Variables. Applied Statistics 1968;17:118–36. [Google Scholar]