Abstract

Introduction

Critically ill patients with acute respiratory, neurological or cardiovascular failure requiring invasive mechanical ventilation are at high risk of difficult intubation and have organ dysfunctions associated with complications of intubation and anaesthesia such as hypotension and hypoxaemia. The complication rate increases with the number of intubation attempts. Videolaryngoscopy improves elective endotracheal intubation. McGRATH MAC is the lightest videolaryngoscope and the most similar to the Macintosh laryngoscope. The primary goal of this trial was to determine whether videolaryngoscopy increased the frequency of successful first-pass intubation in critically ill patients, compared to direct view Macintosh laryngoscopy.

Methods and analysis

MACMAN is a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled superiority trial. Consecutive patients requiring intubation are randomly allocated to either the McGRATH MAC videolaryngoscope or the Macintosh laryngoscope, with stratification by centre and operator experience. The expected frequency of successful first-pass intubation is 65% in the Macintosh group and 80% in the videolaryngoscope group. With α set at 5%, to achieve 90% power for detecting this difference, 185 patients are needed in each group (370 in all). The primary outcome is the proportion of patients with successful first-pass orotracheal intubation, compared between the two groups using a generalised mixed model to take the stratification factors into account.

Ethics and dissemination

The study project has been approved by the appropriate ethics committee (CPP Ouest 2, # 2014-A00674-43). Informed consent is not required, as both laryngoscopy methods are considered standard care in France; information is provided before study inclusion. If videolaryngoscopy proves superior to Macintosh laryngoscopy, its use will become standard practice, thereby decreasing first-pass intubation failure rates and, potentially, the frequency of intubation-related complications. Thus, patient safety should benefit. Further studies would be warranted to determine whether videolaryngoscopy is also beneficial in the emergency room and for prehospital emergency care.

Trial registration number

NCT02413723; Pre-results.

Keywords: ANAESTHETICS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled superiority trial.

Use of successful first-pass intubation as the primary outcome.

Powered to detect a 15% increase in the first-pass intubation success rate with videolaryngoscopy; therefore, a smaller but possibly clinically important true difference might be missed.

Introduction

Background and rationale

This manuscript was written in accordance with the SPIRIT guidelines.1

(A) Endotracheal intubation (ETI) is performed in intensive care units (ICUs) as an emergency procedure in patients with unstable critical illnesses. This setting is associated with an increased frequency of difficult intubation, compared to intubation for surgery (10% to 20% vs 3% to 5%).2–4 The combined presence in many ICU patients of multiple organ dysfunctions, a small physiological reserve and a high risk of difficult intubation translates into a high frequency of intubation-related complications, ranging from 25% to 40%.5 6 The risk of complications increases with the number of intubation attempts.7 8

Several preventive measures are available for minimising the frequency and severity of intubation-related complications. Anaesthetic agents proven effective and safe for rapid sequence intubation (RSI)9–11 must be used if not contraindicated. RSI requires the concomitant administration of a fast-acting neuromuscular blocker, that is, succinylcholine or rocuronium, to facilitate the procedure and limit the risk of gastric content aspiration.12 Also recommended is preoxygenation for 3 min at least, if needed using non-invasive ventilation (NIV).13 Finally, fluid resuscitation and vasopressor support must be started early to ensure haemodynamic stability during ETI. When used in combination as part of a standardised protocol, these measures considerably decrease the risk of complications.14 Many professional societies recommend the use of such a protocol, with training of all staff members and routine capnography before ETI.15 16

The preventive measures described above decrease the risk of complications but fail to increase the frequency of successful first-pass ETI, a major determinant of intubation-related complications. Measures capable of increasing the frequency of successful first-pass ETI are needed. At present, use of a Macintosh laryngoscope with a metal blade is the reference standard for RSI.17 Over the past few years, however, videolaryngoscopes providing a full indirect view of the glottis have shown promise for facilitating ETI. Several studies compared various commercially available videolaryngoscopes, but most focused on ETI in the operating room for elective surgery. Their results suggest that benefits from videolaryngoscopy may be greatest in those patients at risk of difficult intubation.18–21 A 2014 meta-analysis suggested that videolaryngoscopy might be useful in the ICU.22 However, most of the studies had methodological weaknesses such as an observational23–25 or before/after26 27 design or a randomised design but a small sample size and/or single-centre patient recruitment.28 29 Studies performed more recently suggested benefits from videolaryngoscopy but either failed to routinely use neuromuscular blockade,8 29 in contradiction of current guidelines, or included patients with highly specific characteristics.30 Furthermore, most studies of videolaryngoscopy were performed in the specific setting of difficult intubation31 32 (table 1).

Table 1.

Recapitulation of previous studies on ETI with videolaryngoscopy in the intensive care unit or emergency department

| First author | Device | Operators | Centre | Design | Number of ETI procedures | First-pass success (DL vs VL) | p Value | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies showing higher first-pass success rates with VL | ||||||||

| Lakticova | Glidescope | Fellow | Single-centre | Before/after | 140 | 54% vs 79% | 0.0001 | |

| Kory | Glidescope | PCCM fellow | Single-centre | Retrospective | 138 | 68% vs 91% | <0.01 | |

| Silverberg | Glidescope | PCCM fellow | Single-centre | Randomised | 117 | 40% vs 74% | <0.01 | |

| Mosier | Glidescope/CMAC | PCCM/CCM fellow | Single-centre | Retrospective | 290 | 60.7% vs 78.6% | 0.009 | |

| Vassiliadis | CMAC | Mixed | Single-centre | Retrospective | 619 | 85% vs 81,6% | 0.023 | |

| Griesdale | Glidescope | Non-anaesthesiology residents | Single-centre | Randomised | 40 | 95% vs 58% | 0.03 | |

| Studies showing similar or higher first-pass success rates with DL | ||||||||

| Michailidou | Glidescope/CMAC | PGY | Single-centre | Prospective observational | 709 | 71% vs 76% | 0.17 | Trauma centre |

| Ural | Glidescope | Residents in various fields | Single-centre | Before/after | 103 | 73% vs 76% | 0.66 | |

| De Jong | McGRATH MAC | Mixed | Single-centre | Before/after | 210 | 69% vs 79% | 0.09 | |

| Noppens | CMAC | Mixed | Single-centre | Before/after | 274 | 79% vs 88% | 0.08 | |

| Platts-Mills | Glidescope | Residents | Single-centre | Prospective observational | 280 | 84% vs 81% | 0.59 | Trauma centre |

| Yeatts | Glidescope | Residents | Single-centre | Randomised | 623 | 81% vs 80% | 0.46 | Trauma centre |

CCM, critical care medicine; DL, direct laryngoscopy; ETI, endotracheal intubation; PCCM, pulmonary critical care medicine; PGY, post-graduate year physicians; VL, videolaryngoscopy.

(B) We chose the McGRATH MAC videolaryngoscope as the comparator, because its curved blade resembles that of the Macintosh laryngoscope and provides a direct view of the glottis and an indirect view via the camera, a combination that is helpful in the event of oropharyngeal malalignment. More specifically, our choice of the McGRATH MAC videolaryngoscope was based on three considerations:

Intubators with experience using the Macintosh laryngoscope should be able to use the McGRATH MAC videolaryngoscope easily, as the blade curves are similar;

The video monitor of the McGRATH MAC videolaryngoscope allows continuous supervision by a senior intubator when ETI is performed by a junior intubator; and

The McGRATH MAC videolaryngoscope is the lightest weight videolaryngoscope available and can be stored in a small prehospital-care ambulance.

The main purpose of this study is to evaluate whether using videolaryngoscopy for ETI decreases the frequencies of ETI failure and complications, by increasing the first-pass ETI success rate via better visualisation of the glottis, for all ETI procedures performed in ICU patients.

Objectives

Primary objective: To determine whether McGRATH MAC videolaryngoscopy improves the frequency of successful first-pass ETI compared to Macintosh laryngoscopy in patients admitted to the ICU and requiring orotracheal intubation.

Secondary objectives: To determine whether McGRATH MAC videolaryngoscopy for ETI decreases mortality and morbidity and to assess the safety of McGRATH MAC videolaryngoscopy.

Trial design

MACMAN is a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled superiority trial.

Methods: participants, interventions and outcomes

Study setting

The MACMAN trial is taking place in seven ICUs in seven hospitals (five university and two general hospitals) in France.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Patients must be admitted to an ICU and require mechanical ventilation through an endotracheal tube.

Exclusion criteria

Patients are excluded if they meet one or more of the following criteria:

Contraindication to orotracheal intubation (eg, unstable spinal lesion);

Insufficient time to include and randomise the patient (eg, because of cardiac arrest);

Age <18 years;

Pregnant or breastfeeding woman;

Correctional facility inmate;

Patient under guardianship;

Patient without health insurance;

Refusal of the patient or next of kin to participate in the study;

Previous enrolment in a clinical randomised trial with intubation as the primary end point (including previous inclusion in the present trial).

Interventions

Concomitant treatments in both groups

Patients are evaluated for factors known to predict difficult intubation and/or difficult ventilation (body mass index, mouth opening, thyromental distance, Mallampati score, history of snoring, missing teeth, sleep apnoea syndrome).33 The results of this evaluation are recorded in the electronic case report form (eCRF).

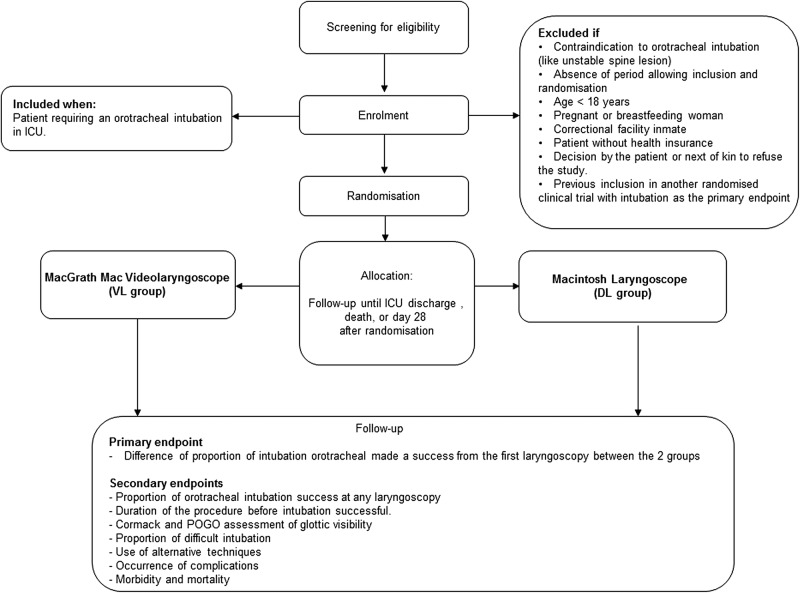

ETI is performed in both groups according to the protocol outlined below (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow chart. DL, direct laryngoscopy; ICU, intensive care unit; POGO, percentage of glottic opening; VL, videolaryngoscopy.

(A) Preoxygenation is achieved using the device chosen by the doctor in charge of the patient:

Bag valve mask delivering oxygen at a minimum flow of 15 L/min for at least 3 min.34 35

Non-rebreathing (high concentration) mask delivering oxygen at a minimum flow of 15 L/min for at least 3 min.36

Ventilator in NIV mode providing 100% FiO2 for at least 3 min;

High-flow nasal oxygen device (eg, Optiflow) delivering oxygen at a minimum flow of 60 L/min, with 100% FiO2, for at least 3 min.37

(B) Anaesthesia is then induced by injecting a hypnotic agent and a neuromuscular blocking agent. The type and dosage of these drugs are at the discretion of the intubating physician. Nevertheless, in agreement with international38 and French guidelines,39 the following two principles are applied:

The preferred neuromuscular blocking agent in the absence of contraindications (eg, hyperkalaemia, burn injury more than 24 h earlier, spinal lesion or allergy) is succinylcholine in a dosage of 1 mg/kg. The alternative is rocuronium 1 mg/kg, provided the antidote sugammadex (16 mg/kg) is available.

If possible, the hypnotic agent is either hypnomidate 0.2–0.3 mg/kg or ketamine 1–2 mg/kg.

(C) Laryngoscopy is performed using the device allocated at random:

McGRATH MAC videolaryngoscope or

Macintosh laryngoscope.

The first attempt with the McGRATH MAC videolaryngoscope is performed using the monitor. The final visualisation method (direct or indirect via the monitor) is recorded in the eCRF. The size of the endotracheal tube and the size of the Macintosh laryngoscope are chosen by the intubating physician.

(D) ETI is then performed. The cuff of the endotracheal tube is inflated and the tube is connected to the ventilator. If this first ETI attempt fails, the physician chooses between repeating the same laryngoscopy technique or switching to an alternative ETI technique. The choice of the alternative ETI technique is at the physician's discretion and in accordance with French guidelines.40 Each introduction of the laryngoscope into the oral cavity of the patient is considered a separate laryngoscopy attempt. Use of Sellick's manoeuvre (pressure applied to the cricoid cartilage) during ETI is at the discretion of the intubating physician and is recorded in the eCRF. The intratracheal tube position is confirmed by analysing the capnography curve over four or more breathing cycles. Total ETI duration is defined as the time from anaesthesia induction initiation to observation of the first inflection on the expired capnography curve (confirming the intratracheal tube position). All items in the eCRF are analysed in real time by a person not involved in patient care. Offline analysis of laryngoscopic intubation is not performed.

All investigators attended a meeting about the trial before inclusion of the first patient. The investigators and coinvestigators received hands-on training in the use of the McGRATH MAC videolaryngoscope and Macintosh laryngoscope.

Outcomes

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome measure is the proportion of successful first-pass ETIs.

Secondary outcome measures

Proportion of successful ETIs at any laryngoscopy attempt;

Total time to successful ETI, defined as the time from anaesthesia induction initiation to confirmation of intratracheal endotracheal tube position based on the partial pressure of end-tidal exhaled carbon dioxide (PetCO2);

Cormack-Lehane grade of glottis visibility;

Percentage of glottic opening scale score;

Proportion of patients with difficult intubation;

- Proportion of patients intubated using alternative techniques, namely,

- Gum elastic bougie,

- Laryngeal mask airway (eg, Fastrach),

- Videolaryngoscope proven to be helpful in difficult orotracheal intubation (Airtraq or GlideScope),

- Fibre-optic endoscopy,

- Rescue percutaneous or surgical transtracheal oxygenation.

- Occurrence of complications:

- Broken teeth,

- Aspiration of gastric content,

- Oesophageal intubation,

- Severe desaturation (SpO2<90%),

- Severe hypotension (systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg),

- Cardiac arrest.

- Variables reflecting morbidity:

- Duration of mechanical ventilation,

- Duration of ICU stay,

- Duration of hospital stay,

- ICU mortality,

- Day-28 mortality.

Participant timeline

The participant timeline is described in table 2.

Table 2.

Participant timeline

| D0 Inclusion |

D0 Preoxygenation |

D0 Intubation |

D1 to D2 | End of ICU stay | D28 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eligibility: check inclusion and exclusion criteria | X | |||||

| Informed consent | X | |||||

| Demographic data | X | |||||

| Randomisation | X | |||||

| Patient characteristics | X | |||||

| Physical examination | X | X | X | X | ||

| Laboratory tests | X | X | X | X | ||

| Treatments | X | X | X | |||

| Final extubation | X | |||||

| Vital status | X | X | X | X |

D, day; ICU, intensive care unit.

Sample size

On the basis of previous data,26 41 42 we expect first-pass ETI to be successful in 65% of patients in the Macintosh group. Assuming that using McGRATH MAC increases this proportion to 80%, with α set at 5% and β at 10%, 185 patients are needed in each group, that is, 370 patients in all.

Recruitment

Patient inclusion started in June 2015 in seven French ICUs. Enrolment is ongoing. As of 11 August 2015, 111 patients had been included. Recruitment-rate enhancing strategies were deemed unnecessary, an opinion borne out by the higher-than-anticipated recruitment rate so far.

Methods: assignment of interventions

Allocation

Randomisation is centralised, web-based and accessible 24 h a day. The randomization scheme is balanced (1:1) and stratified by centre and intubator status, characterised as expert or non-expert. An expert intubator is defined as a doctor who has either worked in ICUs for at least 5 years or has worked in ICUs for at least 1 year after receiving at least 2 years of training in anaesthesia. All intubators who do not meet these criteria are classified as non-experts.43 Details on the intubators will be recorded in the eCRF, notably resident/junior/fellow/senior status and specialty of residency training if appropriate (anaesthesia; emergency department; other).

Sequence generation

The randomisation sequence was generated by a statistician working at the Clinical Research Unit and not involved in patient recruitment. Randomisation was performed in blocks. The software used to collect the data in the eCRFs automatically allocates the patients, thereby ensuring concealment. In each ICU, the physicians and a clinical research nurse and/or clinical research assistant screen the patients around the clock and include those who are eligible for the study.

Blinding

Blinding of healthcare workers and patients (despite the sedation) to the type of laryngoscopy device is not feasible. However, the primary outcome is assessed on the basis of an objective capnography criterion.

Methods: data collection, management and analysis

Data collection and management

The study data are recorded in a web-based eCRF. They are extracted from the medical records of each patient (source data) by the ICU staff. The data manager, in cooperation with the coordinating investigator, establishes the trial database by exporting data from the eCRFs. Any protocol deviations are recorded in either the eCRF or the medical records; both are checked by a clinical research assistant to ensure that all protocol deviations and adverse events are in the database.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis

A predefined statistical analysis plan will be followed, using SAS software V.9.3 (Cary, North Carolina, USA), with the intent-to-treat approach. The statistical analysis will incorporate all the elements required by the CONSORT statement for non-pharmacological interventions.

Description of the patient groups at baseline

The baseline features of the overall population and of each group will be described, using n (%) for categorical variables and the minimum, maximum, mean, SD and quartiles for quantitative variables. No statistical test will be performed to compare the two groups at baseline.

Analysis of the primary outcome

The proportion of patients with successful first-pass ETI will be compared between the two groups using a generalised mixed model to take the stratification factors into account. A sensitivity analysis based on the MACOCHA score for predicting difficult intubation33 will be carried out.

Analysis of secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes will be analysed using generalised mixed models (linear or logistic depending on the variable type). These models will allow us to take into account the stratification of the randomisation scheme on centre (considered to have random effects) and operator experience (considered to have a fixed effect).

For all statistical tests, p values of 0.05 or less will be taken to indicate a significant difference.

Subgroup analysis

We will perform a separate analysis of patients with difficult intubation, defined as three or more laryngoscopies and/or a total ETI duration longer than 10 min.

Methods: monitoring

Data monitoring

Before the start of patient recruitment, all physicians and other healthcare workers in the seven participating ICUs attended formal training sessions on the study protocol and data collection in the eCRF. All documents required for the study are available in each ICU. The eCRF is a secure, interactive, web-response system available at each study centre, provided and managed by the biometrics unit of the Nantes University Hospital (Nantes, France). In each participating ICU, the physicians and a clinical research nurse and/or clinical research assistant are in charge of daily patient screening and inclusion, ensuring compliance with the study protocol and collecting the study data in the eCRFs.

The principal investigators meet with the ICU teams to discuss any problems with data collection and protocol compliance and to evaluate study progress.

According to French law, the eCRF and creation of the database were approved by the appropriate committees (CCTIRS, Comité Consultatif sur le Traitement de l'Information en matière de Recherche dans le domaine de la Santé, N 14 779, on 23 December 2014; and CNIL, Commission Nationale de l'Informatique et des Libertés, N° MMS/VCS/AR1412251, on 16 February 2015).

Harms

The trial may be temporarily stopped for an individual patient, at the discretion of the attending physician, in case of major serious adverse events suspected to be associated with the type of laryngoscope used. According to French law, since the strategies used in both study arms are classified as standard care, no specific reporting procedure for unexpected serious adverse events is planned.

Auditing

The Clinical Research Unit of the La Roche-sur-Yon Hospital reviews the screening forms and clinical data at regular intervals.

Ethics and dissemination

Research ethics approval

The trial is conducted in compliance with the current version of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The research project was approved by the appropriate Ethics Committee for the Protection of Patients (CPP Ouest 2) in Angers, France, on 18 July 2014 (registration number 2014-A00674-43).

Consent or assent

According to French law, since the strategies used in both study groups are considered components of standard care, there is no requirement for consent. Nevertheless, information of the patient or next of kin is required. The patient or next of kin confirms in writing that he/she has received this information. If no next of kin can be contacted during the screening for the study, trial inclusion is conducted as an emergency procedure by the ICU physician, in compliance with French law. Patients who regain consciousness are informed about the trial as soon as possible.

A patient may leave the trial at any time if the person informed about the study (patient or next of kin) is unwilling to continue in the trial. Data from patients who request full withdrawal will not be taken into account in the analysis.

Confidentiality

The study data will be handled as requested by the French Data Protection Authority (CNIL, Commission Nationale de l'Informatique et des Libertés). All original records will be kept on file at the trial sites or coordinating data managing centre for 15 years. The cleaned electronic trial database file will be anonymised and kept on file for 15 years.

Declaration of interests

None of the authors has any financial or other competing interests in relation to this study.

Aircraft Medical Limited, which produces the McGRATH MAC videolaryngoscope, had no role in the design of this study and will have no role in its conduct; data collection, analysis or interpretation; or decision to submit the results for publication.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the MACMAN trial is the first randomised multicentre study of videolaryngoscopy for ETI in ICU patients. Previous studies of this strategy had several weaknesses, including the use of a before-after design26 or patient recruitment at a single centre.28–30 Moreover, most of these studies had no formal ETI protocol designed to limit bias due to variations in anaesthesia induction and/or preoxygenation.24 Also, operator experience was not usually taken into account.

The MACMAN trial has an open-label design, as blinding to the type of laryngoscope used is not feasible. However, the main outcome measure is objective: it is the presence of an inflection on the expired capnography curve, indicating that the tube is in the trachea. ETI duration was the primary outcome measure in many studies. However, ETI duration measurement may lack reliability, as the start and end may be challenging to pinpoint. Other studies used the glottis view quality. However, obtaining a good view does not necessarily translate into successful ETI, and scoring of the view of the glottis is somewhat subjective. In addition, given the low frequency of serious complications, detecting a statistically significant difference in this variable would have required a very large sample size. Moreover, several studies showed a strong correlation between the frequency of complications and the number of laryngoscopy attempts.7 A larger number of attempts translates into a longer duration of ETI and therefore into a higher risk of aspiration and a greater degree of laryngeal oedema, which decreases the effectiveness of facemask ventilation and increases the risk of desaturation during ETI.

In conclusion, if the main hypothesis is confirmed, videolaryngoscopy will become the reference standard for ETI in ICU patients. Expected benefits of this practice are improved patient safety, via decreases in ETI duration and in the frequency of serious complications (episodes of profound hypoxaemia and cardiac arrest). Videolaryngoscopy would also deserve consideration for use outside the ICU, in settings where emergent ETI is often required (emergency rooms and prehospital emergency-care units) and is a source of substantial morbidity.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the clinical staff at the trial sites; A. Wolfe, MD, for assistance in preparing and reviewing the manuscript; S. Martin, PharmD, and E. Greau, RN, for reviewing the manuscript; and E. Le Blanc for managing the database.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Clinical Research in Intensive Care and Sepsis Group (CRICS).

Contributors: AB prepared the first draft of the manuscript. AB, JBL and JR wrote the manuscript. JBL and JR participated in designing the MACMAN study. ALT wrote the statistical analysis plan and estimated the sample size. JBL obtained funding for the study. All authors contributed to the acquisition of the study data. All authors revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This trial was supported solely by a grant from the District Hospital Centre in La Roche Sur Yon, France.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: CPP Ouest 2.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The steering committee will be happy to share data from this trial with researchers after analysis of requests.

References

- 1.Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Gotzsche PC et al. . SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013;346:e7586 10.1136/bmj.e7586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crosby ET, Cooper RM, Douglas MJ et al. . The unanticipated difficult airway with recommendations for management. Can J Anaesth 1998;45:757–76. 10.1007/BF03012147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz DE, Matthay MA, Cohen NH. Death and other complications of emergency airway management in critically ill adults. A prospective investigation of 297 tracheal intubations. Anesthesiology 1995;82:367–76. 10.1097/00000542-199502000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mort TC. The incidence and risk factors for cardiac arrest during emergency tracheal intubation: a justification for incorporating the ASA Guidelines in the remote location. J Clin Anesth 2004;16:508–16. 10.1016/j.jclinane.2004.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griesdale DE, Bosma TL, Kurth T et al. . Complications of endotracheal intubation in the critically ill. Intensive Care Med 2008;34:1835–42. 10.1007/s00134-008-1205-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaber S, Amraoui J, Lefrant JY et al. . Clinical practice and risk factors for immediate complications of endotracheal intubation in the intensive care unit: a prospective, multiple-center study. Crit Care Med 2006;34:2355–61. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000233879.58720.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mort TC. Emergency tracheal intubation: complications associated with repeated laryngoscopic attempts. Anesth Analg 2004;99:607–13. 10.1213/01.ANE.0000122825.04923.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakles JC, Chiu S, Mosier J et al. . The importance of first pass success when performing orotracheal intubation in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2013;20:71–8. 10.1111/acem.12055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jabre P, Combes X, Lapostolle F et al. . Etomidate versus ketamine for rapid sequence intubation in acutely ill patients: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2009;374:293–300. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60949-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duwat A, Turbelin A, Petiot S et al. . [French national survey on difficult intubation in intensive care units]. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 2014;33:297–303. 10.1016/j.annfar.2014.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Orbany M, Connolly LA. Rapid sequence induction and intubation: current controversy. Anesth Analg 2010;110:1318–25. 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181d5ae47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Filippo A, Gonnelli C. Rapid sequence intubation: a review of recent evidences. Rev Recent Clin Trials 2009;4:175–8. 10.2174/157488709789957556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baillard C, Fosse JP, Sebbane M et al. . Noninvasive ventilation improves preoxygenation before intubation of hypoxic patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:171–7. 10.1164/rccm.200509-1507OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaber S, Jung B, Corne P et al. . An intervention to decrease complications related to endotracheal intubation in the intensive care unit: a prospective, multiple-center study. Intensive Care Med 2010;36:248–55. 10.1007/s00134-009-1717-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cook TM, Woodall N, Harper J et al. . Major complications of airway management in the UK: results of the Fourth National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Difficult Airway Society. Part 2: intensive care and emergency departments. Br J Anaesth 2011;106:632–42. 10.1093/bja/aer059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henderson JJ, Popat MT, Latto IP et al. . Difficult Airway Society guidelines for management of the unanticipated difficult intubation. Anaesthesia 2004;59:675–94. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03831.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amour J, Marmion F, Birenbaum A et al. . Comparison of plastic single-use and metal reusable laryngoscope blades for orotracheal intubation during rapid sequence induction of anesthesia. Anesthesiology 2006;104:60–4. 10.1097/00000542-200601000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walker L, Brampton W, Halai M et al. . Randomized controlled trial of intubation with the McGrath Series 5 videolaryngoscope by inexperienced anaesthetists. Br J Anaesth 2009;103:440–5. 10.1093/bja/aep191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenstock CV, Thogersen B, Afshari A et al. . Awake fiberoptic or awake video laryngoscopic tracheal intubation in patients with anticipated difficult airway management: a randomized clinical trial. Anesthesiology 2012;116:1210–16. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318254d085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ng I, Sim XL, Williams D et al. . A randomised controlled trial comparing the McGrath((R)) videolaryngoscope with the straight blade laryngoscope when used in adult patients with potential difficult airways. Anaesthesia 2011;66:709–14. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06767.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aziz MF, Dillman D, Fu R et al. . Comparative effectiveness of the C-MAC video laryngoscope versus direct laryngoscopy in the setting of the predicted difficult airway. Anesthesiology 2012;116:629–36. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318246ea34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Jong A, Molinari N, Conseil M et al. . Video laryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for orotracheal intubation in the intensive care unit: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med 2014;40:629–39. 10.1007/s00134-014-3236-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guyette FX, Farrell K, Carlson JN et al. . Comparison of video laryngoscopy and direct laryngoscopy in a critical care transport service. Prehosp Emerg Care 2013;17:149–54. 10.3109/10903127.2012.729128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mosier JM, Whitmore SP, Bloom JW et al. . Video laryngoscopy improves intubation success and reduces esophageal intubations compared to direct laryngoscopy in the medical intensive care unit. Crit Care 2013;17:R237 10.1186/cc13061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kory P, Guevarra K, Mathew JP et al. . The impact of video laryngoscopy use during urgent endotracheal intubation in the critically ill. Anesth Analg 2013;117:144–9. 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182917f2a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Jong A, Clavieras N, Conseil M et al. . Implementation of a combo videolaryngoscope for intubation in critically ill patients: a before-after comparative study. Intensive Care Med 2013;39:2144–52. 10.1007/s00134-013-3099-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noppens RR, Geimer S, Eisel N et al. . Endotracheal intubation using the C-MAC(R) video laryngoscope or the Macintosh laryngoscope: a prospective, comparative study in the ICU. Crit Care 2012;16:R103 10.1186/cc11384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griesdale DE, Chau A, Isac G et al. . Video-laryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy in critically ill patients: a pilot randomized trial. Can J Anaesth 2012;59:1032–9. 10.1007/s12630-012-9775-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silverberg MJ, Li N, Acquah SO et al. . Comparison of video laryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy during urgent endotracheal intubation: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med 2015;43:636–41. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yeatts DJ, Dutton RP, Hu PF et al. . Effect of video laryngoscopy on trauma patient survival: a randomized controlled trial. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013;75:212–19. 10.1097/TA.0b013e318293103d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu L, Yue H, Li J. Comparison of three tracheal intubation techniques in thyroid tumor patients with a difficult airway: a randomized controlled trial. Med Princ Pract 2014;23:448–52. 10.1159/000364875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maharaj CH, Higgins BD, Harte BH et al. . Evaluation of intubation using the AirtraqÒ or Macintosh laryngoscope by anaesthetists in easy and simulated difficult laryngoscopy—a manikin study. Anaesthesia 2006;61:469–77. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2006.04547.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Jong A, Molinari N, Terzi N et al. . Early identification of patients at risk for difficult intubation in the intensive care unit: development and validation of the MACOCHA score in a multicenter cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;187:832–9. 10.1164/rccm.201210-1851OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCrory JW, Matthews JN. Comparison of four methods of preoxygenation. Br J Anaesth 1990;64:571–6. 10.1093/bja/64.5.571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hett DA, Geraghty IF, Radford R et al. . Routine pre-oxygenation using a Hudson mask. A comparison with a conventional pre-oxygenation technique. Anaesthesia 1994;49:157–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1994.tb03377.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robinson A, Ercole A. Evaluation of the self-inflating bag-valve-mask and non-rebreather mask as preoxygenation devices in volunteers. BMJ Open 2012;2:pii: e001785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miguel-Montanes R, Hajage D, Messika J et al. . Use of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy to prevent desaturation during tracheal intubation of intensive care patients with mild-to-moderate hypoxemia. Crit Care Med 2015;43:574–83. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sinclair RC, Luxton MC. Rapid sequence induction. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain 2005;5:45–8. 10.1093/bjaceaccp/mki016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jung B, Chanques G, Sebbane M et al. . Les modalités de l'intubation en urgence et ses complications. Réanimation 2008;17:753–60. 10.1016/j.reaurg.2008.09.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Langeron O, Bourgain JL, Laccoureye O et al. . [Difficult airway algorithms and management: question 5. Societe Francaise d'Anesthesie et de Reanimation]. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 2008;27:41–5. 10.1016/j.annfar.2007.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang HE, Seitz SR, Hostler D et al. . Defining the learning curve for paramedic student endotracheal intubation. Prehosp Emerg Care 2005;9:156–62. 10.1080/10903120590924645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roux D, Reignier J, Thiery G et al. . Acquiring procedural skills in ICUs: a prospective multicenter study*. Crit Care Med 2014;42:886–95. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simpson GD, Ross MJ, McKeown DW et al. . Tracheal intubation in the critically ill: a multi-centre national study of practice and complications. Br J Anaesth 2012;108:792–9. 10.1093/bja/aer504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]