Abstract

Thrombotic events, both arterial and venous, are a major health concern worldwide. Further, autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis, and antiphospholipid syndrome, predispose to thrombosis, and thereby push the risk for these morbid events even higher. In recent years, neutrophils have been identified as important players in both arterial and venous thrombosis. Specifically, chromatin-based structures called neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) play a key role in activating the coagulation cascade, recruiting platelets, and serving as scaffolding upon which the thrombus can be assembled. At the same time, neutrophils and NETs are emerging as important mediators of pathogenic inflammation in the aforementioned autoimmune diseases. Here, we first review the general role of NETs in thrombosis. We then posit that exaggerated NET release contributes to the prothrombotic diatheses of systemic lupus erythematosus, ANCA-associated vasculitis, and antiphospholipid syndrome.

Keywords: Thrombosis, Neutrophil extracellular traps, Lupus, Vasculitis, Antiphospholipid syndrome

Core tip: In order to capture and kill pathogens, neutrophils release webs of chromatin and antimicrobial proteins called neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). These NETs are also emerging as important players in inflammatory and thrombotic disorders. In this review, we describe the mechanisms by which the various components of NETs promote thrombosis. Further, we highlight emerging evidence that NETs may play a particularly important role when thrombosis occurs in patients with systemic autoimmune diseases such as lupus, vasculitis, and antiphospholipid syndrome.

INTRODUCTION

Blood vessel occlusion attributable to thrombosis is a major health concern in both the United States and worldwide. Most United States studies have suggested annual incidence for venous thromboembolism (VTE) on the order of 1/1000. For example, a classic retrospective study reviewed medical records in Minnesota from 1966 through 1990, and found a VTE incidence of 117 per 100000[1]. A more recent community study addressed VTE incidence in Worcester, Massachusetts and found a similar incidence of 104 per 100000[2]. In Norway, incidence of first VTE is at a similar level, estimated at 1.43 per 1000 person years[3].

VTE morbidity is especially problematic in hospitals. For example, a multinational cross-sectional study of the acute inpatient setting noted that VTE, and specifically pulmonary embolism, accounted for 5%-10% of deaths in hospitalized patients[4]. It should also be noted that VTE carries a high risk of not just morbidity, but also death. In the aforementioned Worcester population study, acute all-cause mortality in patients with VTE was 6.6%[2]. Another United States community-based study, found 28-d mortality following VTE to be 11%, with that risk climbing to 25% in patients with cancer-associated thrombosis[5]. The aforementioned Norwegian study found the risk of death to be especially high following pulmonary embolism, specifically 2.1-fold higher than for deep vein thrombosis (DVT)[3].

Similar to VTE, cardiovascular disease (CVD), especially myocardial infarction and stroke, is a major cause of worldwide morbidity and mortality. CVD results from an inflammatory vasculopathy of arteries called atherosclerosis, which places patients at risk for acute arterial occlusions and downstream ischemia. Global data from the late 1990s suggest that on the order of one-third of all deaths worldwide are caused by CVD[6]. It has also been suggested that access to healthcare plays a critical role in the morbidity attributable to events like strokes, with countries in eastern Europe, north Asia, central Africa, and the south Pacific having particularly high levels of disability following such events[7].

While thrombotic events are clearly a major problem in the general population, the risk is further amplified in the setting of many systemic autoimmune diseases. For example, a meta-analysis of VTE risk in such diseases (excluding pregnant and postoperative patients) found an increased risk that was particularly striking in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis, with odds ratios of 7.29 and 7.97, respectively[8]. Another study of SLE patients found a 7.6% risk of thrombosis over approximately 10 years, which climbs as high as 20.1% in the presence of a particular class of autoantibodies referred to as antiphospholipid antibodies (discussed in more detail below)[9]. When an ANCA-associated vasculitis cohort was followed for six years, there was a 12% prevalence of VTE[10]; interestingly, the incidence was 1.8 per 100 person-years when disease was quiescent, and climbed to 6.71 per 100 during active disease[10].

Patients with systemic autoimmune diseases are also at high risk for CVD. For example, in a prospective cohort of SLE patients, 48% of deaths were attributable to CVD, with risk factors including smoking, endothelial activation, elevated C-reactive protein, and antiphospholipid antibodies[11]. SLE patients may be at particular risk for cerebrovascular events[12], with some studies suggesting that more than 20% of mortality may be attributable to stroke[13]. CVD has similarly been documented at increased levels in ANCA-associated vasculitis, with a rate of acute myocardial infarction that is at least 2.5-times higher than expected based on traditional cardiovascular risk factors[14].

NEUTROPHIL EXTRACELLULAR TRAPS

The neutrophil, as the most abundant leukocyte in circulating blood, plays a critical role in the innate immune system[15-20]. Formed in the bone marrow from myeloid precursors[21], neutrophils are then released into the bloodstream. From there, they can be recruited to sites of inflammation/infection in response to endogenous or pathogen-derived chemoattractants[17,20]. One strategy by which neutrophils target and kill microbes is phagocytosis[22]. Once pathogens are captured in intracellular vacuoles, they are destroyed by reactive oxygen species (oxidative burst)[23] and antimicrobial proteins (degranulation)[24]. Upon the completion of phagocytosis, neutrophils generally undergo apoptosis before being ingested by neighboring macrophages as inflammation resolves[25-27]. For decades, phagocytosis was considered to be the primary mechanism by which neutrophils targeted infections; however, that perception changed with the discovery of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) - one of the most interesting and intensively-studied aspects of neutrophil biology in recent years.

NETs target pathogens

NET release (or NETosis), as first described by Brinkmann et al[18] in 2004, is an active form of neutrophil death that releases a web of chromatin and antimicrobial proteins into the extracellular space. At the core of NETs are chromatin fibers (about 17 nm in diameter) composed of DNA and histones, positively-charged proteins that normally function in the nucleus to package DNA and regulate gene expression. These fibers are further lined by granule-derived antimicrobial proteins such as neutrophil elastase, myeloperoxidase (MPO), cathepsin G, proteinase 3 (PR3), defensins, and cathelicidin LL-37. NETs target pathogens by a combination of sequestration (preventing their dissemination in the body) and highly-localized microbicidal activity[18]. Both Gram-negative (Shigella flexneri[18], Klebsiella pneumoniae[28]) and Gram-positive (Streptococcus aureus[29], Listeria monocytogenes[30]) bacteria can be targeted by NETs, as can fungi (Candida albicans[31], Aspergillus nidulans[32], Aspergillus fumigatus[33]). NETs have also been shown to be effective in killing particular protozoans and viruses[34-36]. Intriguing recent work has demonstrated that neutrophils are capable of sensing differences in microbe size such that NETs are preferentially released when the neutrophil is confronted by larger pathogens and microbial clusters that cannot be engulfed by phagocytosis[37].

It is also interesting to note that certain microbes have evolved mechanisms for evading NETs. For example, surface modification may dampen neutrophil activation and NET binding[38-40]. Also, pathogen-derived nucleases are well established as destabilizers of NETs[41-43]. That NETs form an important arm of antimicrobial innate immunity is exemplified by the fact that defects in NET generation, or experimental NET depletion, increase susceptibility to various kinds of infections in mice and humans[28,44-49].

Mechanisms of NET release

NET release can be triggered by a variety of stimuli including microbes, pharmacological agents (phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate and calcium ionophore[50]), inflammatory cytokines (interleukin 8[51], tumor necrosis factor α[52]), growth factors (granulocyte colony-stimulating factor[53]), activated endothelial cells[54], activated platelets[55], and immune complexes[56]. Following this initial trigger, various pathways intersect to facilitate the extrusion of NETs. For example, some think of NETosis as a variant of autophagy since netting neutrophils display characteristics of autophagy including the formation of autophagosomes[57]. Indeed, inhibition of autophagy-associated signaling prevents NETosis in some contexts[58]. Generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase complex has also been considered by many as an absolute prerequisite to NET formation[48,59,60]. Mechanistically, protein kinase C activation[61] and RAF/MEK/ERK signaling[62] lead to phosphorylation of gp91phox[63], p67phox[64], and p47phox[65], which results in assembly of the functional NADPH oxidase complex for ROS generation. However, recent evidence has also shown that activation of SK3 potassium channels, mediated by calcium influx, may lead to an alternative, NADPH oxidase-independent mechanism of NETosis[66].

Once activated, neutrophils preparing for NETosis flatten and adhere tightly to the substratum. ROS are generated and cytoplasmic granules disintegrate releasing their contents into the cytoplasm. Neutrophil elastase then migrates to the nucleus, where it degrades linker histone H1 and processes core histones, thereby promoting chromatin relaxation[28]. This is followed by the translocation to the nucleus of MPO, which also binds chromatin and promotes decondensation, albeit by an unknown mechanism[28]. In addition, the relaxation of chromatin is further promoted by post-translational modification of histone arginine residues to neutral citrullines by the enzyme peptidylarginine deiminase 4 (PAD4)[46,67-69]. Following dissolution of the nuclear membrane, the plasma membrane ruptures casting NETs into the extracellular space[48].

It should be noted that the above description is of what is sometimes called “suicidal” NETosis. However, NETs can also be released in more rapid fashion, in a manner that does not lead to neutrophil death. This concept of “vital” NETosis, which especially occurs in the context of the direct interaction between neutrophils and microorganisms, has been described in detail in a recent review article[70].

HOW DO NETS PROMOTE THROMBOSIS?

Thrombosis results from dysregulation of normally-protective hemostatic systems, with the end result being a clot in the vessel lumen and obstruction of blood flow. If the occlusion is not resolved, it can have marked consequences including infarction, embolization, and even death. Blood coagulation can be initiated by two classic pathways. The first, historically termed “extrinsic”, starts with the release of thrombogenic tissue factor from endothelium and leukocytes, while the second “intrinsic” pathway is initiated by the activation of circulating clotting factors on negatively-charged surfaces. Both of these pathways converge at a common point (factor X) with the subsequent activation of the protease factor II (also called thrombin). Thrombin then converts fibrinogen into insoluble fibrin, which is indispensable for clot formation[71]. Platelet activation (associated with the release of procoagulant polyphosphates among other bioactive molecules) and platelet aggregation (to form a platelet plug) are also important processes in normal hemostasis, as well as pathologic thrombosis[72,73]. These pathways are further regulated by natural anticoagulants like tissue factor pathway inhibitor, antithrombin, thrombomodulin, and protein C, which act on various targets to limit thrombin generation[74].

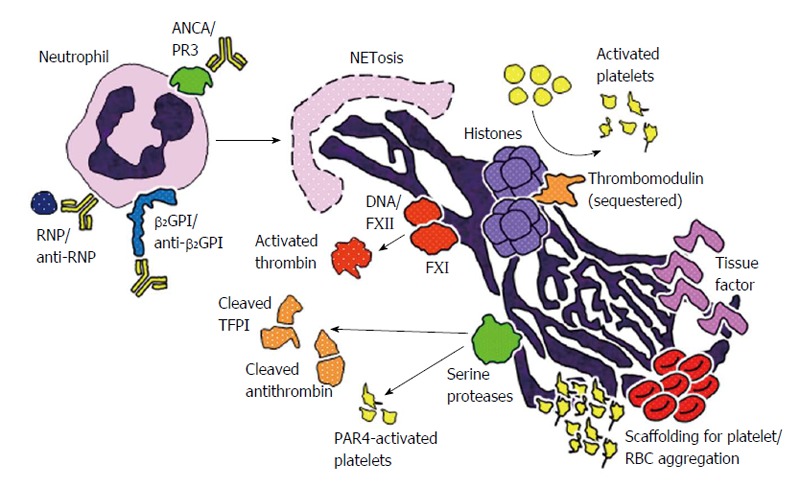

NETs are now known to be an integral component of thrombi, and actually essential for thrombosis in many contexts (Figure 1). NETs serve as structural scaffolding for entrapment and aggregation of platelets and erythrocytes[75]. Additionally, negatively-charged NETs bind plasma proteins like fibrinogen, fibronectin, and von Willebrand factor (VWF), thereby stabilizing the clot[75]. In animal models, it has been shown that dismantling NETs by deoxyribonuclease (DNase) treatment or knocking out PAD4 (an enzyme essential for NET formation) diminishes thrombosis[76-79]. Mechanistically, interesting studies, using both in vitro and in vivo systems, have shown that several NET components are capable of contributing to coagulation and thrombus formation (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of potential mechanisms by which neutrophil extracellular traps may promote thrombosis in systemic autoimmune diseases. First, a number of stimuli may promote NETosis in systemic autoimmune diseases including ribonucleoprotein (RNP)/anti-RNP complexes in systemic lupus erythematosus, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) engagement with surface proteinase 3 (PR3) in vasculitis, and the interaction of anti-beta-2 glycoprotein I (β2GPI) with surface β2GPI in antiphospholipid syndrome. The DNA component of NETs activates factor XII (FXII), initiating a cascade (along with factor XI) that ultimately leads to the formation of thrombin. Histones in NETs activate platelets and sequester certain anticoagulant molecules like thrombomodulin and protein C. Neutrophil serine proteases present in NETs, such as neutrophil elastase and cathespin G, cleave the anticoagulant molecules tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) and antithrombin, and also activate platelets through various pathways including protease-activated receptor 4. NETs also may present procoagulant tissue factor in some contexts. Finally, NETs serve as scaffolding for the assembly and aggregation of platelets and red blood cells (RBCs). NET: Neutrophil extracellular trap.

Table 1.

Neutrophil extracellular trap-associated molecules that may play a role in promoting thrombosis

| NET component | Role in thrombosis |

| DNA backbone | Negatively charged surface capable of activating factor XII[80] |

| Coassembly of TFPI and serine proteases at thrombus[86] | |

| Histones | Platelet activation[83,84] |

| Prevent activation of natural anticoagulant, protein C[85] | |

| Elastase | Cleavage of TFPI[86] |

| Cleavage of antithrombin[87] | |

| Strips proteoglycan layer of arterial media to expose VWF[88] | |

| Cathepsin G | Cleavage of TFPI[86] |

| Platelet activation[89,90] | |

| Tissue factor | Platelet activation[91,104] |

| Thrombin generation by extrinsic pathway of coagulation[91,104] |

TFPI: Tissue factor pathway inhibitor; VWF: Von Willebrand factor; NET: Neutrophil extracellular trap.

DNA backbone

Coagulation factor XII, a plasma serine protease capable of activating factor XI and prekallikrein, is recognized as the traditional initiator of the intrinsic pathway. factor XII is well known to be activated by negatively-charged surfaces both in vitro and in vivo, and it turns out that the anionic backbone of NETs (i.e., DNA) is a capable activator of factor XII[80]. It has consequently been shown that factor XIIa (the activated form) can contribute to thrombus formation by both factor XI-dependent and independent mechanisms[81,82].

Histones

As mentioned above, histones are positively-charged proteins that normally function to package DNA in the nucleus; they are also the most abundant proteins in NETs. Histones trigger platelet activation and thrombin generation in a dose-dependent manner[83,84]. Indeed, upon treatment with histones, platelets exhibit several activation-associated characteristics such as aggregation, exposure of phosphatidylserines, and surface expression of P-selectin[83,84]. The ability of histones to activate platelets seems to be at least partially dependent on signaling through platelet Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and TLR4[83,84], with a further contribution from several notable intracellular pathways including ERK, Akt, p38, and nuclear factor-κB. Importantly, when histones complex with DNA (as is observed in NETs), their ability to promote platelet activation and thrombin generation is further amplified[84]. Intersecting with coagulation pathways, histone-activated platelets release polyphosphates, which potently promote thrombin activation[84]. Independent of platelets, it has also been suggested that histones contribute to the activation of thrombin by sequestering thrombomodulin and protein C (a natural anticoagulant), and thereby preventing thrombomodulin-dependent activation of protein C[85]. These varied experiments (primarily done with purified components in vitro) have been supported by work in animal models, where infusion of histones promotes DVT formation in mice in the context of inferior vena cava flow restriction[76].

Serine proteases: Neutrophil elastase and cathepsin G

Granule-derived serine proteases, which are among the most abundant non-histone proteins in NETs, potentially engage with blood coagulation in a number of ways. For example, mice deficient in neutrophil elastase and cathepsin G exhibit defects in tissue factor activation, fibrin formation, and thrombus stabilization[86]; in this system, at least one function of the proteases is to degrade an antagonist of coagulation, tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI). Interestingly, the DNA component of NETs is required for the coassembly of TFPI and the proteases, thereby inactivating TFPI at the point of thrombosis[86].

Other mechanisms have also been described. Neutrophil elastase promotes the proteolytic cleavage of the anticoagulant antithrombin[87]. Elastase (in cooperation with matrix metalloproteinase 9) also degrades the proteoglycan network of the arterial media, thereby exposing collagen for VWF binding and platelet adhesion[88]. Further, cathespin G can promote a procoagulant state by cleaving and activating platelet protease activated receptor 4 signaling, thereby enhancing thrombus formation and fibrin deposition under flow conditions[89,90].

Tissue factor

In 2012, von Brühl et al[80] showed that the combination of intravascular NET formation and tissue factor are essential for development of thrombi in a mouse model of DVT. The NETs were not only decorated with tissue factor, but also with protein disulfide isomerase, which can activate it. In this system, the tissue factor was felt to originate especially from monocytes, before migrating to, and activating on, the NETs[80]. However, in neutrophils isolated from patients with sepsis, neutrophils themselves seem to be the source of tissue factor, utilizing the machinery of autophagy to deliver tissue factor to the NETs[91]; indeed, in this context, tissue factor-bearing NETs can stimulate both thrombin generation and platelet activation ex vivo.

NETS AND THROMBOTIC EVENTS

Arterial and venous thrombotic events, despite certain common risk factors, are pathophysiologically-distinct processes[92,93]. For example, arterial thrombosis is particularly dependent on platelets since, under the high shear stress of arterial flow, platelets are effective at adhering to the vessel wall[94]. Rupture of atherosclerotic plaques (as in CVD) leads to marked platelet activation and aggregation, and ultimately to the development of platelet-rich “white” clots. In contrast, an important factor in venous thrombosis is a reduction in blood flow (stasis) with the development of red blood cell-rich “red” thrombi that result from the local accumulation and activation of circulating coagulation factors[95]. Interestingly, as the components of NETs are capable of activating both platelets and the coagulation cascade, NETs may be a unifying link/risk factor for the two processes. This notion has been validated in the animal models and clinical studies that are highlighted below.

Venous thrombosis

In one clinical study, 150 patients with symptomatic DVT were compared to controls who had clinical suspicion for DVT, but negative objective testing[96]. As compared to controls, patients with DVT had higher levels of both circulating nucleosomes and activated neutrophils, with elevated levels of either suggesting an approximately three-fold risk of DVT[96]. Another group obtained venous thromboembolism specimens from 11 patients and classified these into various stages of thrombus organization based on morphological characteristics[97]. Immunochemical staining suggested that NETs were especially present in organizing venous thrombi, indicating that they play an important role in thrombus maturation[97].

Experimentally, restriction (stenosis) of blood flow in the iliac vein of baboons[75] or the inferior vena cava of mice[76,80], results in elevation of plasma DNA levels and development of NET-containing venous thrombi. Further, in this model, infusion of histones increases both thrombus size and plasma levels of VWF, with the latter potentially contributing to platelet activation and recruitment[76]. Importantly, neutrophil depletion results in comparatively smaller thrombi[80], as does treatment with DNase[76]. Thrombus formation is also abrogated in PAD4-knockout mice, which are deficient in NET production[79]. In the PAD4 knockouts, thrombosis could be rescued by infusion of wild-type neutrophils[79], arguing that PAD4’s role in thrombosis is at the level of neutrophils (and presumably NETosis).

Cardiovascular disease and arterial thrombosis

Correlation studies have hinted at a relationship between DNA, NETosis, and atherosclerotic/atherothrombotic disease[98]. In a cohort of 282 patients with well-characterized coronary artery disease, severity of disease was predicted by levels of circulating cell-free DNA as well as a number of NET markers (nucleosomes, citrullinated histone H4, and MPO-DNA complexes)[98]. Further, these markers also correlated with evidence of active coagulation (soluble CD163 and thrombin-antithrombin complexes)[98]. In mice, NETs can be detected in close association with plaques in the carotid lumen of atherosclerosis-prone ApoE(-/-) mice[99], while the PAD4 inhibitor Cl-amidine (which also blocks NETosis) prevents NET formation and decreases atherosclerotic lesion area in this model[77]. Mechanistically, the cathelicidin-derived proteins LL-37 (human) and CRAMP (mouse), which are abundant in NETs, seem to promote atherosclerosis[100,101]. For example, Döring et al[102] demonstrated that CRAMP-DNA complexes stimulate plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) to produce type I interferons that promote plaque growth, a phenotype that could be reversed by either CRAMP deficiency or degradation of the DNA backbone of NETs.

Regarding arterial thrombosis, coronary thrombi can be rich in NETs as detected by immunochemical staining[103]; the authors of this study were particularly interested in the role of neutrophil interleukin-17A/F, and indeed both cytokines were present in not only neutrophils, but NETs themselves[103]. It has also been suggested that NETs present in the thrombi of acute myocardial infarctions expose tissue factor, which is functional in activating both thrombin generation and platelets when studied ex vivo[104]. However, that functionality was lost with digestion of the DNA backbone of NETs[104]. Finally, in a mouse model of arterial wall injury by ferric chloride, NET nucleosomes, as well as neutrophil serine proteases (elastase and cathepsin G), are essential for thrombus formation[86].

SLE

SLE is a systemic autoimmune disease that preferentially affects women. While the etiology of SLE is not fully understood, it is widely accepted that a hallmark of SLE is the near universal detection of an “antinuclear” autoimmune response. In particular, autoantibodies form to double-stranded DNA and to ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes. These autoantibodies participate in immune complex formation, with subsequent deposition in organs such as the kidneys (where they cause glomerulonephritis). Given the key roles of both autoantibodies and immune complexes in SLE pathogenesis, the majority of research over the years has understandably focused on abnormalities in the adaptive immune system, with particular attention paid to B cells, T cells, and antigen-presenting cells. However, in recent years, increasing attention has been paid to mediators of the innate immune response, especially neutrophils, which release NETs[105], and pDCs, which manufacture large quantities of type I interferons[106].

Regarding NETs, some patients with SLE have a deficiency in circulating DNase function, and therefore an impaired ability to degrade NETs in plasma[107,108]. This DNase defect fluctuates, and has been shown to correlate with both glomerulonephritis and hypocomplementemia[109]. Not surprisingly, the levels of circulating NETs themselves have also been shown to correlate with nephritis[110].

While impaired degradation surely plays a role in the increased levels of circulating NETs[110], the situation is further exacerbated by the increased propensity of SLE neutrophils to undergo NETosis[111-113]. In some cases this is likely a result of stimulation by circulating autoantibodies, such as anti-RNP and anti-LL-37, which are common in SLE patients[111,112,114]. In other cases, enhanced NETosis may be attributable to environmental factors, like low vitamin D levels[115], or increased susceptibility to infection resulting from treatment with immunosuppressive drugs. Accelerated NETosis may also stem from inherent differences in SLE neutrophils, as evidenced by their lower density (sometimes referred to as low-density granulocytes) and their proinflammatory phenotype[113]. Further, SLE NETs may be especially potent stimulators of the immune system. For example, they contain LL-37, which stimulates both pDCs and macrophages[112,116]. The immunostimulatory potential of SLE NETs may also be further amplified by acetylated histones and demethylated DNA[117,118].

As is discussed above, the risk of thrombotic events, both arterial and venous, is significant in SLE patients[119,120]. From an arterial perspective, the relative risk for myocardial infarction and stroke are both increased (10- and 7-fold, respectively) relative to that seen in the general population[121]. Similarly, the risk of DVT and pulmonary embolism is increased at least 10-fold in SLE[122]. Other venous complications, such as retinal vein occlusion[123], also stand out as more common. Further, it should be noted that with improved treatment of organ-threatening SLE manifestations such as kidney disease, 50% of SLE patients now die of some type of cardiovascular disease[11].

NETs, endothelial damage, and thrombosis in SLE

An important intersection between NETs and the vasculature involves the ability of SLE NETs to engage TLRs and thereby promote the formation of type I interferons by pDCs[111-113]. Type I interferons then play a multifaceted role in endothelial dysfunction, accelerating foam cell formation and impairing endothelial progenitor numbers and function[124,125]. Further, given the abundance of neutrophils in circulation (especially relative to rare cells like pDCs), it is noteworthy that netting neutrophils may themselves be a source of type I interferons in SLE[113,126].

In addition to promoting the production of potentially anti-vascular cytokines like type I interferons, NETs may also play a direct role in endothelial damage in SLE[113]. For example, SLE NETs contain matrix metalloproteinase-9, which activates endothelial matrix metalloproteinase-2, and thereby triggers endothelial cell death[127]. Endothelial damage may be further compounded in SLE by the NET- and MPO-mediated oxidation of high-density lipoprotein (HDL), which causes HDL to lose its normally vasculoprotective properties[128].

The best evidence for a role of NETs in not just the vascular damage, but also the prothrombotic diathesis of SLE, comes from mouse models of the disease. Indeed, NETs play an important role in pathogenesis of some[78,129], but not all[130], SLE models. In the NZM2328 model, NET release can be prevented by treatment with an inhibitor of PAD4 that prevents histone citrullination and consequently NETosis[78]. Over time, PAD inhibition protects against endothelial damage as measured by an acetylcholine-dependent vascular relaxation assay[78]. NZM2328 mice are also prothrombotic at baseline, rapidly forming carotid thrombi after photochemical injury of the endothelium. These carotid thrombi are rich in neutrophils and NETs, and can be prevented by treatment with either DNase or a PAD inhibitor[125]. These findings are reminiscent of work in models of atherosclerosis, where NETs are important in not just vascular damage[100,102], but also thrombosis[77]. Whether prevention of NETosis can protect against thrombotic disease in patients with SLE remains to be determined, although it is noteworthy that antimalarial drugs like chloroquine both block NETosis[128], and track with a reduced risk of thrombosis in patients[131].

ANCA-ASSOCIATED VASCULITIS

ANCA-associated vasculitis describes a group of closely-related relapsing-remitting diseases, characterized by (1) small-vessel inflammation that especially targets the lungs and kidneys; and (2) autoantibodies against the neutrophil granule proteins MPO and PR3. The two best characterized syndromes are microscopic polyangiitis, in which patients are typically positive for anti-MPO, and granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s), which classically has anti-PR3 positivity. Neutrophils/NETs and ANCA likely interact in two important ways: (1) NETs contain both MPO and PR3 and may thereby stimulate the autoimmune response to these antigens; and (2) ANCA can interact with neutrophils to promote NET release, with NETs then contributing to vascular and organ damage.

Consistent with NETs playing a role in ANCA induction, netting neutrophils are more efficient than apoptotic neutrophils in loading murine myeloid dendritic cells with MPO and PR3[132]. This efficiency is dependent on the DNA backbone of NETs, as it can be almost completely abrogated with DNase[132]. NET-loaded dendritic cells induce glomerulonephritis in mice[132], while myeloid dendritic cells can be detected interacting with netting neutrophils in skin samples from patients with microscopic polyangiitis[132]. The ability of NETs to induce ANCA has also been observed anecdotally in patients, for example, in the setting of infectious endocarditis apparently driving both anti-PR3 formation and glomerulonephritis[133].

Mechanisms of ANCA-mediated NET release

Mechanistically, ANCA likely promote NETosis by engaging granule proteins that have migrated to the cell surface in primed neutrophils[134]. Indeed, one study found that ANCA are more potent than SLE IgG in this regard, and further that ANCA-associated NETosis correlates well with vasculitic disease activity[135]. The mechanism of NET induction by a nontraditional ANCA, anti-lysosomal membrane protein-2 (LAMP-2), has recently been investigated in detail. It appears that anti-LAMP-2 directs neutrophils away from apoptosis and toward NETosis by activating the vacuolization typically seen in autophagy[136]. Whether autophagy machinery is also required for NETosis mediated by traditional ANCA (anti-PR3 and anti-MPO) remains to be elucidated.

When NETs form in ANCA patients, they are relatively resistant to degradation by plasma DNase, an effect that is not explained by a direct effect of ANCA on DNase itself[135]. Along similar lines, the anti-thyroid drug propylthiouracil (PTU) is a recognized inducer of ANCA production in humans; in an animal model, PTU leads to the formation of NETs that are particularly resistant to DNase-mediated degradation, thereby exacerbating both pulmonary capillaritis and glomerulonephritis[137]. It was recently shown that ANCA-induced NETs appear to be relatively potent activators of the alternative complement cascade[138], and can also promote both platelet activation and conversion of pentameric C-reactive protein (CRP) into prothrombotic monomeric CRP[139].

ANCA-mediated NETs and thrombosis

NETs have been found in close proximity to inflamed glomeruli in vasculitic kidneys[134], as well as in vasculitic skin lesions[140], arguing that NETs play a role in tissue toxicity. It has also been suggested that NETs play a particular role in ANCA-associated thrombotic events, especially venous. For example, thrombi obtained from ANCA vasculitis patients are particularly rich in both NETs[141] and histone citrullination[142].

An intriguing mechanistic role has also been suggested for tissue factor[143]. Specifically, Kambas et al[143] demonstrated tissue factor-positive NETs in sera, bronchoalveolar lavage fluids, and renal biopsies of ANCA vasculitis patients. Further, tissue factor-positive NETs and microparticles correlated with higher disease activity (similar to thrombosis), and could be induced when control neutrophils were treated with ANCA in vitro[143]. How unique these phenotypes are to ANCA-associated NETs, as compared to NETs that form in other infectious and inflammatory diseases, remains to be determined.

ANTIPHOSPHOLIPID SYNDROME

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), an autoimmune disease of unknown etiology, is among the most common acquired causes of both thrombosis and pregnancy loss in the United States. About half of APS cases are diagnosed in patients with lupus, and the remainder as a standalone syndrome called primary APS[144]. Primary APS manifests not just with thrombosis and pregnancy loss, but also with additional features including livedo reticularis, thrombocytopenia, chorea, leg ulcers, cognitive dysfunction, seizures, alveolar hemorrhage, and nephropathy[145]. This heterogeneity of manifestations clearly points to APS as a truly systemic autoimmune disease on the spectrum of lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, and small-vessel vasculitis.

Pathophysiology of APS

Despite the name of the syndrome (anti-phospholipid), the best understood antigen in APS is not a phospholipid, but rather a lipid-binding protein that circulates at high levels in blood (100-200 μg/mL) called beta-2 glycoprotein I (β2GPI). Autoantibodies to β2GPI activate various types of cells in vitro[146-149], and promote both thrombosis and pregnancy loss when injected into mice[150,151]. Currently, three assays are used to diagnose APS clinically. These include tests for (1) anti-cardiolipin antibodies; (2) anti-β2GPI antibodies; and (3) a group of coagulation assays collectively referred to as “lupus anticoagulant” - functional testing that takes advantage of the fact that antiphospholipid antibodies paradoxically prolong phospholipid-dependent clotting assays in vitro. It is interesting to note that ELISAs for anti-cardiolipin are often actually detecting anti-β2GPI, with the reactivity to cardiolipin mediated by β2GPI protein present in the patient’s serum. Antibodies to thrombin may also sometimes cause APS, although testing has not been standardized, and anti-thrombin is therefore not routinely assessed in clinical practice. In summary, this group of antibodies is (despite the inaccuracy) referred to as antiphospholipid antibodies, with anti-β2GPI being the best characterized and the most likely to be pathogenic.

While antiphospholipid antibodies are recognized to be pathogenic, the origin of these antibodies, and the reason that lupus patients are especially at risk for their development, are not well understood. Further, there are currently no targeted treatments for APS. Instead, therapy focuses on masking the prothrombotic effects of antiphospholipid antibodies with anticoagulant medications like warfarin and heparin. These drugs often need to be taken for life, and at the same time predispose to catastrophic bleeding complications[152]. While anticoagulants are somewhat effective in preventing APS-associated blood clotting, they often have no bearing on the neurologic and renal complications of APS, which can progress to organ failure[145].

Heightened NET release in APS

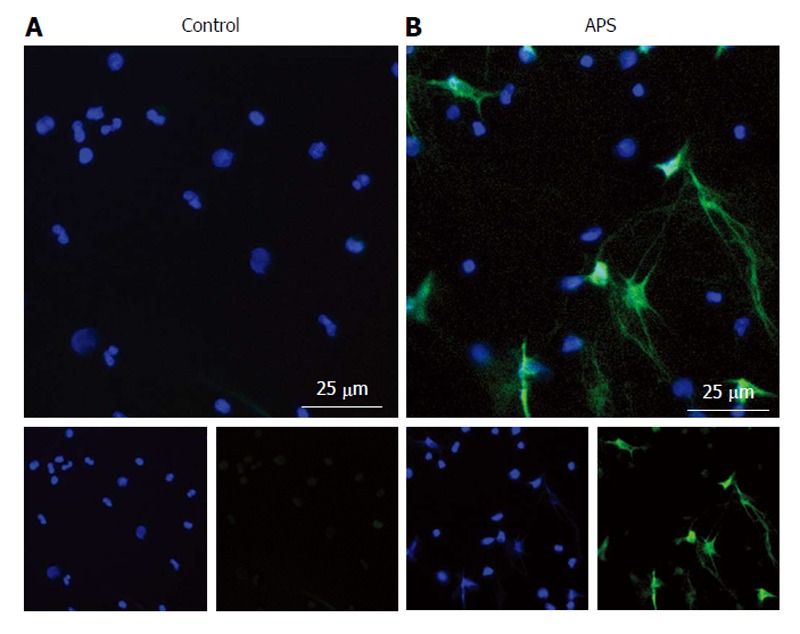

Our group has recently made a number of important observations about APS neutrophils[153]. First, NETs circulate at high levels in the plasma of APS patients, even between thrombotic episodes[153]. Indeed, freshly isolated neutrophils from APS patients are primed to undergo spontaneous NETosis when cultured ex vivo (Figure 2). Mechanistically, anti-β2GPI IgG promotes NETosis by engaging β2GPI protein on the neutrophil surface; this process is independent of the Fc receptor, but does require ROS production and TLR4 signaling[153]. Further, and pointing to disease relevance, anti-β2GPI-stimulated NETs promote thrombin generation in vitro[153]. In addition to our work, Leffler et al[154] have shown that some patients with APS have a defect in DNase-mediated NET degradation. This potentially sets up a vicious prothrombotic cycle, in which the threshold for NETosis is reduced in APS neutrophils, followed by the exaggerated persistence of the NETs that do form. A final interesting point is that antiphospholipid antibodies seem to engage not just neutrophils[153], but NETs themselves[154]. This observation deserves further exploration as to its potential role in APS pathogenesis.

Figure 2.

Antiphospholipid syndrome neutrophils are prone to “spontaneous” neutrophil extracellular trap release. Freshly-isolated neutrophils from a healthy control (A) or antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) patient (B) were seeded onto poly-lysine-coated coverslips and incubated in serum-free media for 2 h. Samples were then fixed with paraformaldehyde and stained with Hoechst 33342 (DNA = blue) and anti-neutrophil elastase (Abcam, green). Cells were not specifically permeabilized and neutrophil elastase staining is therefore primarily extracellular. These representative micrographs show more neutrophil extracellular trap release in the APS neutrophils, as determined by overlapping DNA and neutrophil elastase staining.

CONCLUSION

While NETs have yet to be assigned a clear function in normal hemostasis, their roles in venous thrombosis, atherosclerosis, and arterial occlusions continue to be defined. It is notable that many systemic autoimmune diseases are not only associated with increased NETosis and decreased NET clearance, but also demonstrate an increased risk of both arterial and venous events. We therefore find it quite plausible that NETs contribute to the prothrombotic nature of diseases like SLE, ANCA-associated vasculitis, and APS. As is detailed above, there are also hints that these sterile inflammatory NETs may differ structurally from NETs released during infection (for example, by being enriched in tissue factor or being more resistant to degradation), although further study in this area is clearly needed. More work in disease-specific experimental models will also be required before clinical interventions can be considered. In summary, there is a need to continue to explore the association between thrombosis and inflammatory disease-associated NETosis, in order to better understand whether treatment algorithms can be developed that will allow us to prevent, rather than simply treat, life-threatening thrombotic episodes in these at-risk patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ms. Gail Quaderer for administrative support in assembling this manuscript.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Falconi M, Kettering K, Landesberg G, Lee TM S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

Supported by NIH K08AR066569; and a career development award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (Knight JS); Kazzaz NM was supported by Security Forces Hospital Program, Ministry of Interior, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest for this article.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: June 2, 2015

First decision: August 14, 2015

Article in press: October 27, 2015

References

- 1.Silverstein MD, Heit JA, Mohr DN, Petterson TM, O’Fallon WM, Melton LJ. Trends in the incidence of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a 25-year population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:585–593. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.6.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spencer FA, Emery C, Lessard D, Anderson F, Emani S, Aragam J, Becker RC, Goldberg RJ. The Worcester Venous Thromboembolism study: a population-based study of the clinical epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:722–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00458.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naess IA, Christiansen SC, Romundstad P, Cannegieter SC, Rosendaal FR, Hammerstrøm J. Incidence and mortality of venous thrombosis: a population-based study. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:692–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen AT, Tapson VF, Bergmann JF, Goldhaber SZ, Kakkar AK, Deslandes B, Huang W, Zayaruzny M, Emery L, Anderson FA. Venous thromboembolism risk and prophylaxis in the acute hospital care setting (ENDORSE study): a multinational cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2008;371:387–394. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cushman M, Tsai AW, White RH, Heckbert SR, Rosamond WD, Enright P, Folsom AR. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in two cohorts: the longitudinal investigation of thromboembolism etiology. Am J Med. 2004;117:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ounpuu S, Anand S. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: part I: general considerations, the epidemiologic transition, risk factors, and impact of urbanization. Circulation. 2001;104:2746–2753. doi: 10.1161/hc4601.099487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnston SC, Mendis S, Mathers CD. Global variation in stroke burden and mortality: estimates from monitoring, surveillance, and modelling. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:345–354. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JJ, Pope JE. A meta-analysis of the risk of venous thromboembolism in inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16:435. doi: 10.1186/s13075-014-0435-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tektonidou MG, Laskari K, Panagiotakos DB, Moutsopoulos HM. Risk factors for thrombosis and primary thrombosis prevention in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus with or without antiphospholipid antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:29–36. doi: 10.1002/art.24232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stassen PM, Derks RP, Kallenberg CG, Stegeman CA. Venous thromboembolism in ANCA-associated vasculitis--incidence and risk factors. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:530–534. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gustafsson JT, Simard JF, Gunnarsson I, Elvin K, Lundberg IE, Hansson LO, Larsson A, Svenungsson E. Risk factors for cardiovascular mortality in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:R46. doi: 10.1186/ar3759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiu CC, Huang CC, Chan WL, Chung CM, Huang PH, Lin SJ, Chen JW, Leu HB. Increased risk of ischemic stroke in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a nationwide population-based study. Intern Med. 2012;51:17–21. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.6154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Timlin H, Petri M. Transient ischemic attack and stroke in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2013;22:1251–1258. doi: 10.1177/0961203313497416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faurschou M, Mellemkjaer L, Sorensen IJ, Svalgaard Thomsen B, Dreyer L, Baslund B. Increased morbidity from ischemic heart disease in patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1187–1192. doi: 10.1002/art.24386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phillipson M, Kubes P. The neutrophil in vascular inflammation. Nat Med. 2011;17:1381–1390. doi: 10.1038/nm.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mócsai A. Diverse novel functions of neutrophils in immunity, inflammation, and beyond. J Exp Med. 2013;210:1283–1299. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayadas TN, Cullere X, Lowell CA. The multifaceted functions of neutrophils. Annu Rev Pathol. 2014;9:181–218. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020712-164023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, Fauler B, Uhlemann Y, Weiss DS, Weinrauch Y, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004;303:1532–1535. doi: 10.1126/science.1092385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mantovani A, Cassatella MA, Costantini C, Jaillon S. Neutrophils in the activation and regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:519–531. doi: 10.1038/nri3024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kolaczkowska E, Kubes P. Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:159–175. doi: 10.1038/nri3399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borregaard N. Neutrophils, from marrow to microbes. Immunity. 2010;33:657–670. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nordenfelt P, Tapper H. Phagosome dynamics during phagocytosis by neutrophils. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;90:271–284. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0810457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Segal AW. The function of the NADPH oxidase of phagocytes and its relationship to other NOXs in plants, invertebrates, and mammals. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:604–618. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirsch JG, Cohn ZA. Degranulation of polymorphonuclear leucocytes following phagocytosis of microorganisms. J Exp Med. 1960;112:1005–1014. doi: 10.1084/jem.112.6.1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Savill JS, Wyllie AH, Henson JE, Walport MJ, Henson PM, Haslett C. Macrophage phagocytosis of aging neutrophils in inflammation. Programmed cell death in the neutrophil leads to its recognition by macrophages. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:865–875. doi: 10.1172/JCI113970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michlewska S, Dransfield I, Megson IL, Rossi AG. Macrophage phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils is critically regulated by the opposing actions of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory agents: key role for TNF-alpha. FASEB J. 2009;23:844–854. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-121228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silva MT. Macrophage phagocytosis of neutrophils at inflammatory/infectious foci: a cooperative mechanism in the control of infection and infectious inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;89:675–683. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0910536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papayannopoulos V, Metzler KD, Hakkim A, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil elastase and myeloperoxidase regulate the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:677–691. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pilsczek FH, Salina D, Poon KK, Fahey C, Yipp BG, Sibley CD, Robbins SM, Green FH, Surette MG, Sugai M, et al. A novel mechanism of rapid nuclear neutrophil extracellular trap formation in response to Staphylococcus aureus. J Immunol. 2010;185:7413–7425. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munafo DB, Johnson JL, Brzezinska AA, Ellis BA, Wood MR, Catz SD. DNase I inhibits a late phase of reactive oxygen species production in neutrophils. J Innate Immun. 2009;1:527–542. doi: 10.1159/000235860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Urban CF, Reichard U, Brinkmann V, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil extracellular traps capture and kill Candida albicans yeast and hyphal forms. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:668–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bianchi M, Niemiec MJ, Siler U, Urban CF, Reichenbach J. Restoration of anti-Aspergillus defense by neutrophil extracellular traps in human chronic granulomatous disease after gene therapy is calprotectin-dependent. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1243–1252.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCormick A, Heesemann L, Wagener J, Marcos V, Hartl D, Loeffler J, Heesemann J, Ebel F. NETs formed by human neutrophils inhibit growth of the pathogenic mold Aspergillus fumigatus. Microbes Infect. 2010;12:928–936. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abi Abdallah DS, Lin C, Ball CJ, King MR, Duhamel GE, Denkers EY. Toxoplasma gondii triggers release of human and mouse neutrophil extracellular traps. Infect Immun. 2012;80:768–777. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05730-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baker VS, Imade GE, Molta NB, Tawde P, Pam SD, Obadofin MO, Sagay SA, Egah DZ, Iya D, Afolabi BB, et al. Cytokine-associated neutrophil extracellular traps and antinuclear antibodies in Plasmodium falciparum infected children under six years of age. Malar J. 2008;7:41. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saitoh T, Komano J, Saitoh Y, Misawa T, Takahama M, Kozaki T, Uehata T, Iwasaki H, Omori H, Yamaoka S, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps mediate a host defense response to human immunodeficiency virus-1. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Branzk N, Lubojemska A, Hardison SE, Wang Q, Gutierrez MG, Brown GD, Papayannopoulos V. Neutrophils sense microbe size and selectively release neutrophil extracellular traps in response to large pathogens. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:1017–1025. doi: 10.1038/ni.2987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wartha F, Beiter K, Albiger B, Fernebro J, Zychlinsky A, Normark S, Henriques-Normark B. Capsule and D-alanylated lipoteichoic acids protect Streptococcus pneumoniae against neutrophil extracellular traps. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:1162–1171. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heddergott C, Bruns S, Nietzsche S, Leonhardt I, Kurzai O, Kniemeyer O, Brakhage AA. The Arthroderma benhamiae hydrophobin HypA mediates hydrophobicity and influences recognition by human immune effector cells. Eukaryot Cell. 2012;11:673–682. doi: 10.1128/EC.00037-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hong W, Juneau RA, Pang B, Swords WE. Survival of bacterial biofilms within neutrophil extracellular traps promotes nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae persistence in the chinchilla model for otitis media. J Innate Immun. 2009;1:215–224. doi: 10.1159/000205937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berends ET, Horswill AR, Haste NM, Monestier M, Nizet V, von Köckritz-Blickwede M. Nuclease expression by Staphylococcus aureus facilitates escape from neutrophil extracellular traps. J Innate Immun. 2010;2:576–586. doi: 10.1159/000319909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sumby P, Barbian KD, Gardner DJ, Whitney AR, Welty DM, Long RD, Bailey JR, Parnell MJ, Hoe NP, Adams GG, et al. Extracellular deoxyribonuclease made by group A Streptococcus assists pathogenesis by enhancing evasion of the innate immune response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:1679–1684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406641102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walker MJ, Hollands A, Sanderson-Smith ML, Cole JN, Kirk JK, Henningham A, McArthur JD, Dinkla K, Aziz RK, Kansal RG, et al. DNase Sda1 provides selection pressure for a switch to invasive group A streptococcal infection. Nat Med. 2007;13:981–985. doi: 10.1038/nm1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lehrer RI, Cline MJ. Leukocyte myeloperoxidase deficiency and disseminated candidiasis: the role of myeloperoxidase in resistance to Candida infection. J Clin Invest. 1969;48:1478–1488. doi: 10.1172/JCI106114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Metzler KD, Fuchs TA, Nauseef WM, Reumaux D, Roesler J, Schulze I, Wahn V, Papayannopoulos V, Zychlinsky A. Myeloperoxidase is required for neutrophil extracellular trap formation: implications for innate immunity. Blood. 2011;117:953–959. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-290171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li P, Li M, Lindberg MR, Kennett MJ, Xiong N, Wang Y. PAD4 is essential for antibacterial innate immunity mediated by neutrophil extracellular traps. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1853–1862. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meng W, Paunel-Görgülü A, Flohé S, Hoffmann A, Witte I, MacKenzie C, Baldus SE, Windolf J, Lögters TT. Depletion of neutrophil extracellular traps in vivo results in hypersusceptibility to polymicrobial sepsis in mice. Crit Care. 2012;16:R137. doi: 10.1186/cc11442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fuchs TA, Abed U, Goosmann C, Hurwitz R, Schulze I, Wahn V, Weinrauch Y, Brinkmann V, Zychlinsky A. Novel cell death program leads to neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:231–241. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200606027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bianchi M, Hakkim A, Brinkmann V, Siler U, Seger RA, Zychlinsky A, Reichenbach J. Restoration of NET formation by gene therapy in CGD controls aspergillosis. Blood. 2009;114:2619–2622. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-221606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parker H, Dragunow M, Hampton MB, Kettle AJ, Winterbourn CC. Requirements for NADPH oxidase and myeloperoxidase in neutrophil extracellular trap formation differ depending on the stimulus. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;92:841–849. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1211601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gupta AK, Hasler P, Holzgreve W, Gebhardt S, Hahn S. Induction of neutrophil extracellular DNA lattices by placental microparticles and IL-8 and their presence in preeclampsia. Hum Immunol. 2005;66:1146–1154. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Keshari RS, Jyoti A, Dubey M, Kothari N, Kohli M, Bogra J, Barthwal MK, Dikshit M. Cytokines induced neutrophil extracellular traps formation: implication for the inflammatory disease condition. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Demers M, Krause DS, Schatzberg D, Martinod K, Voorhees JR, Fuchs TA, Scadden DT, Wagner DD. Cancers predispose neutrophils to release extracellular DNA traps that contribute to cancer-associated thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:13076–13081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200419109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gupta AK, Joshi MB, Philippova M, Erne P, Hasler P, Hahn S, Resink TJ. Activated endothelial cells induce neutrophil extracellular traps and are susceptible to NETosis-mediated cell death. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:3193–3197. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clark SR, Ma AC, Tavener SA, McDonald B, Goodarzi Z, Kelly MM, Patel KD, Chakrabarti S, McAvoy E, Sinclair GD, et al. Platelet TLR4 activates neutrophil extracellular traps to ensnare bacteria in septic blood. Nat Med. 2007;13:463–469. doi: 10.1038/nm1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Behnen M, Leschczyk C, Möller S, Batel T, Klinger M, Solbach W, Laskay T. Immobilized immune complexes induce neutrophil extracellular trap release by human neutrophil granulocytes via FcγRIIIB and Mac-1. J Immunol. 2014;193:1954–1965. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Remijsen Q, Vanden Berghe T, Wirawan E, Asselbergh B, Parthoens E, De Rycke R, Noppen S, Delforge M, Willems J, Vandenabeele P. Neutrophil extracellular trap cell death requires both autophagy and superoxide generation. Cell Res. 2011;21:290–304. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mitroulis I, Kambas K, Chrysanthopoulou A, Skendros P, Apostolidou E, Kourtzelis I, Drosos GI, Boumpas DT, Ritis K. Neutrophil extracellular trap formation is associated with IL-1β and autophagy-related signaling in gout. PLoS One. 2011;6:e29318. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kirchner T, Möller S, Klinger M, Solbach W, Laskay T, Behnen M. The impact of various reactive oxygen species on the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. Mediators Inflamm. 2012;2012:849136. doi: 10.1155/2012/849136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Parker H, Winterbourn CC. Reactive oxidants and myeloperoxidase and their involvement in neutrophil extracellular traps. Front Immunol. 2012;3:424. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gray RD, Lucas CD, Mackellar A, Li F, Hiersemenzel K, Haslett C, Davidson DJ, Rossi AG. Activation of conventional protein kinase C (PKC) is critical in the generation of human neutrophil extracellular traps. J Inflamm (Lond) 2013;10:12. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-10-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hakkim A, Fuchs TA, Martinez NE, Hess S, Prinz H, Zychlinsky A, Waldmann H. Activation of the Raf-MEK-ERK pathway is required for neutrophil extracellular trap formation. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:75–77. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Raad H, Paclet MH, Boussetta T, Kroviarski Y, Morel F, Quinn MT, Gougerot-Pocidalo MA, Dang PM, El-Benna J. Regulation of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase activity: phosphorylation of gp91phox/NOX2 by protein kinase C enhances its diaphorase activity and binding to Rac2, p67phox, and p47phox. FASEB J. 2009;23:1011–1022. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-114553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dang PM, Morel F, Gougerot-Pocidalo MA, El Benna J. Phosphorylation of the NADPH oxidase component p67(PHOX) by ERK2 and P38MAPK: selectivity of phosphorylated sites and existence of an intramolecular regulatory domain in the tetratricopeptide-rich region. Biochemistry. 2003;42:4520–4526. doi: 10.1021/bi0205754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dewas C, Fay M, Gougerot-Pocidalo MA, El-Benna J. The mitogen-activated protein kinase extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 pathway is involved in formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine-induced p47phox phosphorylation in human neutrophils. J Immunol. 2000;165:5238–5244. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Douda DN, Khan MA, Grasemann H, Palaniyar N. SK3 channel and mitochondrial ROS mediate NADPH oxidase-independent NETosis induced by calcium influx. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:2817–2822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414055112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang Y, Li M, Stadler S, Correll S, Li P, Wang D, Hayama R, Leonelli L, Han H, Grigoryev SA, et al. Histone hypercitrullination mediates chromatin decondensation and neutrophil extracellular trap formation. J Cell Biol. 2009;184:205–213. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200806072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Leshner M, Wang S, Lewis C, Zheng H, Chen XA, Santy L, Wang Y. PAD4 mediated histone hypercitrullination induces heterochromatin decondensation and chromatin unfolding to form neutrophil extracellular trap-like structures. Front Immunol. 2012;3:307. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Neeli I, Khan SN, Radic M. Histone deimination as a response to inflammatory stimuli in neutrophils. J Immunol. 2008;180:1895–1902. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yipp BG, Kubes P. NETosis: how vital is it? Blood. 2013;122:2784–2794. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-457671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Versteeg HH, Heemskerk JW, Levi M, Reitsma PH. New fundamentals in hemostasis. Physiol Rev. 2013;93:327–358. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00016.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rivera J, Lozano ML, Navarro-Núñez L, Vicente V. Platelet receptors and signaling in the dynamics of thrombus formation. Haematologica. 2009;94:700–711. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2008.003178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Heemskerk JW, Mattheij NJ, Cosemans JM. Platelet-based coagulation: different populations, different functions. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:2–16. doi: 10.1111/jth.12045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dahlbäck B. Blood coagulation and its regulation by anticoagulant pathways: genetic pathogenesis of bleeding and thrombotic diseases. J Intern Med. 2005;257:209–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fuchs TA, Brill A, Duerschmied D, Schatzberg D, Monestier M, Myers DD, Wrobleski SK, Wakefield TW, Hartwig JH, Wagner DD. Extracellular DNA traps promote thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:15880–15885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005743107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brill A, Fuchs TA, Savchenko AS, Thomas GM, Martinod K, De Meyer SF, Bhandari AA, Wagner DD. Neutrophil extracellular traps promote deep vein thrombosis in mice. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:136–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04544.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Knight JS, Luo W, O’Dell AA, Yalavarthi S, Zhao W, Subramanian V, Guo C, Grenn RC, Thompson PR, Eitzman DT, et al. Peptidylarginine deiminase inhibition reduces vascular damage and modulates innate immune responses in murine models of atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2014;114:947–956. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Knight JS, Zhao W, Luo W, Subramanian V, O’Dell AA, Yalavarthi S, Hodgin JB, Eitzman DT, Thompson PR, Kaplan MJ. Peptidylarginine deiminase inhibition is immunomodulatory and vasculoprotective in murine lupus. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:2981–2993. doi: 10.1172/JCI67390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Martinod K, Demers M, Fuchs TA, Wong SL, Brill A, Gallant M, Hu J, Wang Y, Wagner DD. Neutrophil histone modification by peptidylarginine deiminase 4 is critical for deep vein thrombosis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:8674–8679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301059110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.von Brühl ML, Stark K, Steinhart A, Chandraratne S, Konrad I, Lorenz M, Khandoga A, Tirniceriu A, Coletti R, Köllnberger M, et al. Monocytes, neutrophils, and platelets cooperate to initiate and propagate venous thrombosis in mice in vivo. J Exp Med. 2012;209:819–835. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gould TJ, Vu TT, Swystun LL, Dwivedi DJ, Mai SH, Weitz JI, Liaw PC. Neutrophil extracellular traps promote thrombin generation through platelet-dependent and platelet-independent mechanisms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:1977–1984. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Konings J, Govers-Riemslag JW, Philippou H, Mutch NJ, Borissoff JI, Allan P, Mohan S, Tans G, Ten Cate H, Ariëns RA. Factor XIIa regulates the structure of the fibrin clot independently of thrombin generation through direct interaction with fibrin. Blood. 2011;118:3942–3951. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-339572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Carestia A, Rivadeneyra L, Romaniuk MA, Fondevila C, Negrotto S, Schattner M. Functional responses and molecular mechanisms involved in histone-mediated platelet activation. Thromb Haemost. 2013;110:1035–1045. doi: 10.1160/TH13-02-0174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Semeraro F, Ammollo CT, Morrissey JH, Dale GL, Friese P, Esmon NL, Esmon CT. Extracellular histones promote thrombin generation through platelet-dependent mechanisms: involvement of platelet TLR2 and TLR4. Blood. 2011;118:1952–1961. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-343061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ammollo CT, Semeraro F, Xu J, Esmon NL, Esmon CT. Extracellular histones increase plasma thrombin generation by impairing thrombomodulin-dependent protein C activation. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:1795–1803. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Massberg S, Grahl L, von Bruehl ML, Manukyan D, Pfeiler S, Goosmann C, Brinkmann V, Lorenz M, Bidzhekov K, Khandagale AB, et al. Reciprocal coupling of coagulation and innate immunity via neutrophil serine proteases. Nat Med. 2010;16:887–896. doi: 10.1038/nm.2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jordan RE, Nelson RM, Kilpatrick J, Newgren JO, Esmon PC, Fournel MA. Inactivation of human antithrombin by neutrophil elastase. Kinetics of the heparin-dependent reaction. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:10493–10500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wohner N, Keresztes Z, Sótonyi P, Szabó L, Komorowicz E, Machovich R, Kolev K. Neutrophil granulocyte-dependent proteolysis enhances platelet adhesion to the arterial wall under high-shear flow. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:1624–1631. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03890.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Faraday N, Schunke K, Saleem S, Fu J, Wang B, Zhang J, Morrell C, Dore S. Cathepsin G-dependent modulation of platelet thrombus formation in vivo by blood neutrophils. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Goel MS, Diamond SL. Neutrophil cathepsin G promotes prothrombinase and fibrin formation under flow conditions by activating fibrinogen-adherent platelets. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9458–9463. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211956200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kambas K, Mitroulis I, Apostolidou E, Girod A, Chrysanthopoulou A, Pneumatikos I, Skendros P, Kourtzelis I, Koffa M, Kotsianidis I, et al. Autophagy mediates the delivery of thrombogenic tissue factor to neutrophil extracellular traps in human sepsis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45427. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lijfering WM, Flinterman LE, Vandenbroucke JP, Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC. Relationship between venous and arterial thrombosis: a review of the literature from a causal perspective. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2011;37:885–896. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1297367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mackman N. Triggers, targets and treatments for thrombosis. Nature. 2008;451:914–918. doi: 10.1038/nature06797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cosemans JM, Angelillo-Scherrer A, Mattheij NJ, Heemskerk JW. The effects of arterial flow on platelet activation, thrombus growth, and stabilization. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;99:342–352. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Esmon CT. Basic mechanisms and pathogenesis of venous thrombosis. Blood Rev. 2009;23:225–229. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.van Montfoort ML, Stephan F, Lauw MN, Hutten BA, Van Mierlo GJ, Solati S, Middeldorp S, Meijers JC, Zeerleder S. Circulating nucleosomes and neutrophil activation as risk factors for deep vein thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:147–151. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Savchenko AS, Martinod K, Seidman MA, Wong SL, Borissoff JI, Piazza G, Libby P, Goldhaber SZ, Mitchell RN, Wagner DD. Neutrophil extracellular traps form predominantly during the organizing stage of human venous thromboembolism development. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12:860–870. doi: 10.1111/jth.12571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Borissoff JI, Joosen IA, Versteylen MO, Brill A, Fuchs TA, Savchenko AS, Gallant M, Martinod K, Ten Cate H, Hofstra L, et al. Elevated levels of circulating DNA and chromatin are independently associated with severe coronary atherosclerosis and a prothrombotic state. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:2032–2040. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Megens RT, Vijayan S, Lievens D, Döring Y, van Zandvoort MA, Grommes J, Weber C, Soehnlein O. Presence of luminal neutrophil extracellular traps in atherosclerosis. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107:597–598. doi: 10.1160/TH11-09-0650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Döring Y, Drechsler M, Wantha S, Kemmerich K, Lievens D, Vijayan S, Gallo RL, Weber C, Soehnlein O. Lack of neutrophil-derived CRAMP reduces atherosclerosis in mice. Circ Res. 2012;110:1052–1056. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.265868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Edfeldt K, Agerberth B, Rottenberg ME, Gudmundsson GH, Wang XB, Mandal K, Xu Q, Yan ZQ. Involvement of the antimicrobial peptide LL-37 in human atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1551–1557. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000223901.08459.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Döring Y, Manthey HD, Drechsler M, Lievens D, Megens RT, Soehnlein O, Busch M, Manca M, Koenen RR, Pelisek J, et al. Auto-antigenic protein-DNA complexes stimulate plasmacytoid dendritic cells to promote atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2012;125:1673–1683. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.046755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.de Boer OJ, Li X, Teeling P, Mackaay C, Ploegmakers HJ, van der Loos CM, Daemen MJ, de Winter RJ, van der Wal AC. Neutrophils, neutrophil extracellular traps and interleukin-17 associate with the organisation of thrombi in acute myocardial infarction. Thromb Haemost. 2013;109:290–297. doi: 10.1160/TH12-06-0425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Stakos DA, Kambas K, Konstantinidis T, Mitroulis I, Apostolidou E, Arelaki S, Tsironidou V, Giatromanolaki A, Skendros P, Konstantinides S, et al. Expression of functional tissue factor by neutrophil extracellular traps in culprit artery of acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:1405–1414. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Knight JS, Kaplan MJ. Lupus neutrophils: ‘NET’ gain in understanding lupus pathogenesis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012;24:441–450. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283546703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Elkon KB, Wiedeman A. Type I IFN system in the development and manifestations of SLE. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012;24:499–505. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283562c3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hakkim A, Fürnrohr BG, Amann K, Laube B, Abed UA, Brinkmann V, Herrmann M, Voll RE, Zychlinsky A. Impairment of neutrophil extracellular trap degradation is associated with lupus nephritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:9813–9818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909927107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Leffler J, Martin M, Gullstrand B, Tydén H, Lood C, Truedsson L, Bengtsson AA, Blom AM. Neutrophil extracellular traps that are not degraded in systemic lupus erythematosus activate complement exacerbating the disease. J Immunol. 2012;188:3522–3531. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Leffler J, Gullstrand B, Jönsen A, Nilsson JÅ, Martin M, Blom AM, Bengtsson AA. Degradation of neutrophil extracellular traps co-varies with disease activity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15:R84. doi: 10.1186/ar4264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zhang S, Lu X, Shu X, Tian X, Yang H, Yang W, Zhang Y, Wang G. Elevated plasma cfDNA may be associated with active lupus nephritis and partially attributed to abnormal regulation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Intern Med. 2014;53:2763–2771. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.53.2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Garcia-Romo GS, Caielli S, Vega B, Connolly J, Allantaz F, Xu Z, Punaro M, Baisch J, Guiducci C, Coffman RL, et al. Netting neutrophils are major inducers of type I IFN production in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:73ra20. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lande R, Ganguly D, Facchinetti V, Frasca L, Conrad C, Gregorio J, Meller S, Chamilos G, Sebasigari R, Riccieri V, et al. Neutrophils activate plasmacytoid dendritic cells by releasing self-DNA-peptide complexes in systemic lupus erythematosus. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:73ra19. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Villanueva E, Yalavarthi S, Berthier CC, Hodgin JB, Khandpur R, Lin AM, Rubin CJ, Zhao W, Olsen SH, Klinker M, et al. Netting neutrophils induce endothelial damage, infiltrate tissues, and expose immunostimulatory molecules in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2011;187:538–552. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Van Avondt K, Fritsch-Stork R, Derksen RH, Meyaard L. Ligation of signal inhibitory receptor on leukocytes-1 suppresses the release of neutrophil extracellular traps in systemic lupus erythematosus. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Handono K, Sidarta YO, Pradana BA, Nugroho RA, Hartono IA, Kalim H, Endharti AT. Vitamin D prevents endothelial damage induced by increased neutrophil extracellular traps formation in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Acta Med Indones. 2014;46:189–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kahlenberg JM, Carmona-Rivera C, Smith CK, Kaplan MJ. Neutrophil extracellular trap-associated protein activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome is enhanced in lupus macrophages. J Immunol. 2013;190:1217–1226. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Pieterse E, Hofstra J, Berden J, Herrmann M, Dieker J, van der Vlag J. Acetylated histones contribute to the immunostimulatory potential of neutrophil extracellular traps in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Immunol. 2015;179:68–74. doi: 10.1111/cei.12359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Coit P, Yalavarthi S, Ognenovski M, Zhao W, Hasni S, Wren JD, Kaplan MJ, Sawalha AH. Epigenome profiling reveals significant DNA demethylation of interferon signature genes in lupus neutrophils. J Autoimmun. 2015;58:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Knight JS, Kaplan MJ. Cardiovascular disease in lupus: insights and updates. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2013;25:597–605. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328363eba3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Bazzan M, Vaccarino A, Marletto F. Systemic lupus erythematosus and thrombosis. Thromb J. 2015;13:16. doi: 10.1186/s12959-015-0043-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Esdaile JM, Abrahamowicz M, Grodzicky T, Li Y, Panaritis C, du Berger R, Côte R, Grover SA, Fortin PR, Clarke AE, et al. Traditional Framingham risk factors fail to fully account for accelerated atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:2331–2337. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200110)44:10<2331::aid-art395>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Chung WS, Lin CL, Chang SN, Lu CC, Kao CH. Systemic lupus erythematosus increases the risks of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a nationwide cohort study. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12:452–458. doi: 10.1111/jth.12518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Yen YC, Weng SF, Chen HA, Lin YS. Risk of retinal vein occlusion in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a population-based cohort study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97:1192–1196. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-303265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Mak A, Kow NY. Imbalance between endothelial damage and repair: a gateway to cardiovascular disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:178721. doi: 10.1155/2014/178721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kaplan MJ, Salmon JE. How does interferon-α insult the vasculature? Let me count the ways. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:334–336. doi: 10.1002/art.30161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Lindau D, Mussard J, Rabsteyn A, Ribon M, Kötter I, Igney A, Adema GJ, Boissier MC, Rammensee HG, Decker P. TLR9 independent interferon α production by neutrophils on NETosis in response to circulating chromatin, a key lupus autoantigen. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:2199–2207. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-203041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Carmona-Rivera C, Zhao W, Yalavarthi S, Kaplan MJ. Neutrophil extracellular traps induce endothelial dysfunction in systemic lupus erythematosus through the activation of matrix metalloproteinase-2. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1417–1424. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Smith CK, Vivekanandan-Giri A, Tang C, Knight JS, Mathew A, Padilla RL, Gillespie BW, Carmona-Rivera C, Liu X, Subramanian V, et al. Neutrophil extracellular trap-derived enzymes oxidize high-density lipoprotein: an additional proatherogenic mechanism in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:2532–2544. doi: 10.1002/art.38703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Knight JS, Subramanian V, O’Dell AA, Yalavarthi S, Zhao W, Smith CK, Hodgin JB, Thompson PR, Kaplan MJ. Peptidylarginine deiminase inhibition disrupts NET formation and protects against kidney, skin and vascular disease in lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:2199–2206. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Campbell AM, Kashgarian M, Shlomchik MJ. NADPH oxidase inhibits the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:157ra141. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]