Abstract

AIM: To review methods of assessing adherence and strategies to improve adherence to cardiovascular disease (CVD) medications, among South Asian CVD patients.

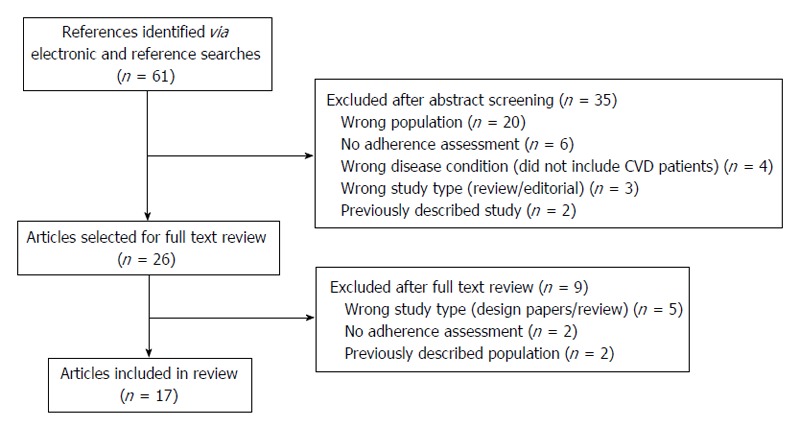

METHODS: We conducted a systematic review of English language studies that examined CVD medication adherence in South Asian populations from 1966 to April 1, 2015 in SCOPUS and PubMed. Working in duplicate, we identified 61 studies. After exclusions, 26 studies were selected for full text review. Of these, 17 studies were included in the final review. We abstracted data on several factors including study design, study population, method of assessing adherence and adherence rate.

RESULTS: These studies were conducted in India (n = 11), Pakistan (n = 3), Bangladesh (n = 1), Nepal (n = 1) and Sri Lanka (n = 1). Adherence rates ranged from 32%-95% across studies. Of the 17 total publications included, 10 focused on assessing adherence to CVD medications and 7 focused on assessing the impact of interventions on medication adherence. The validated Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS) was used as the primary method of assessing adherence in five studies. Three studies used validated questionnaires similar to the MMAS, and one study utilized Medication Event Monitoring System caps, with the remainder of the studies utilizing pill count and self-report measures. As expected, studies using non-validated self-report measures described higher rates of adherence than studies using validated scale measurements and pill count. The included intervention studies examined the use of polypill therapy, provider education and patient counseling to improve medication adherence.

CONCLUSION: The overall medication adherence rates were low in the region, which suggest a growing need for future interventions to improve adherence.

Keywords: Assessing medication adherence, South Asia, Cardiovascular disease medication

Core tip: The overall adherence rate in South Asia is quite low. Only 7 of 17 publications conducted interventions geared toward improving adherence. Even fewer (n = 3) utilized community health care workers, which provide a unique resource in these resource constrained environments. Just over half of the studies found in our review utilized validated or gold standard methods (n = 9) with the rest using non-validated self-reported measures. Additionally, there was a lack of usage of technology despite the majority of these countries benefitting from a high cell phone density.

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide, with an estimated 17.5 million people dying from CVD in 2012[1]. Approximately one-fifth of the global population resides in South Asia (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka), where patients suffer from a disproportionately high rate of CVD-related morbidity and mortality[2-6]. In a large international, case-control study of first myocardial infarction (MI), results indicated that the mean age for first MI was significantly lower in South Asian participants (53.0 years) than in participants from other countries (58.8 years)[5]. In approximately 10% of these cases, first MI in South Asian participants occurred in those aged 40 or below. These data indicate a growing epidemic of premature CVD in South Asian populations.

Use of beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, statins and antiplatelet drugs are successful means of secondary prevention of CVD. However, the use of these drugs varies widely by population. Results of a large-scale epidemiological study examining use of secondary prevention drugs for CVD in high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries showed that use was highest in high-income countries [antiplatelet drugs 62.0%, β blockers 40.0%, ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) 49.8%, and statins 66.5%] and lowest in low-income countries (including India, Bangladesh and Pakistan) (8.8%, 9.7%, 5.2%, and 3.3% for antiplatelets, β blockers, ACE inhibitors or ARBs, and statins, respectively)[7].

An important factor in the use of appropriate medications to manage CVD risk is medication adherence. Adherence is critical to the effectiveness of all drug therapies, but is particularly important for medications prescribed for chronic conditions[8]. In a study of 37154 patients with established atherothrombotic disease, non-adherence to medications at baseline and one year were both significantly associated with increased risk of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke at 4 years[9]. This is of particular importance to South Asian countries for various reasons. First, low availability of electronic medical records in most health care settings precludes accurate assessment of medication adherence by health care providers in these countries and therefore, poses specific challenges in the assessment of medication adherence. Second, the overall health literacy and the opportunities to improve provider and patient awareness of the importance of medication adherence may be limited. Lastly, low availability of pharmacy records and medication refill data also limit the use of traditional measures used to assess medication adherence (i.e., medication possession ratio or proportion of days covered).

Therefore, the overall aim of this review is to examine the current methods of assessing adherence to CVD medications as well as explore current interventional strategies to improve medication adherence, among CVD patients in South Asia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy and study selection

To identify eligible studies, we conducted a systematic search of the literature using the electronic databases PubMed (1966 to April 1, 2015) and SCOPUS (1966 to April 1, 2015) and reviewed reference lists for relevant articles. Major search terms included “medication adherence” OR “adherence medication” OR “enhancing medication adherence” OR “measuring medication adherence” OR “medication adherence scale” OR “Morisky medication adherence scale” OR “interventions for enhancing medication” AND “South Asia” OR “South Asian” OR “India” OR “Pakistan” OR “Sri Lanka” OR “Nepal” OR “Bangladesh” AND “cardiovascular disease” OR “cardiovascular disease medication” OR “cardiovascular disease medicine”.

Working in duplicate, reviewers screened all abstracts and full-text publications for eligibility. The following details were abstracted from included publications: Patient population, sample size, country, study design, adherence measure, definition of adherence and adherence rate.

Eligibility criteria

Eligible studies were defined as fully published (English language) studies that examined CVD medication adherence as the primary or secondary outcome in South Asian populations. English is widely spoken in post-colonial South Asia, and there are very few scientific studies published in native languages in this region. We excluded studies conducted outside of the target population (India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Nepal or Bangladesh), studies not reporting the method of adherence assessment, studies not focused on CVD medications, studies with previously described populations, published reviews and editorials, and studies reporting no results (rationale/design papers) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Results of systematic search. CVD: Cardiovascular disease.

RESULTS

Results of our systematic search of the literature are shown in the Figure 1. A total of 61 studies were identified through electronic and reference searches, and 35 were excluded after abstract review. The majority of abstracts were excluded because the studies were conducted outside of South Asia (n = 20), there was no assessment of adherence reported (n = 6), the therapeutic area was not CVD (n = 4), the paper was a review or editorial (n = 3), or the study population was already included in our review through a different publication (n = 2). Of the 26 articles included in the full-text review, we further excluded 9 articles. The reasons for exclusion of full text articles were that the papers were design/rationale or review papers (n = 5), no adherence assessment was reported (n = 2) and the study population was previously described in an included paper (n = 2). Therefore, the final review included 17 articles. A summary of the included studies is shown in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of studies included in the systematic review

| Ref. | Patient population | Sample size | Country | Design | Adherence measure | Definition of adherence | Adherence rate |

| Joshi et al[25] | Hypertensive patients seeking treatment | 139 | India | Cross-sectional | Pill count | ≥ 80% pills taken | 79% in controlled hypertensives |

| 39% in uncontrolled hypertensives | |||||||

| Ponnusankar et al[32] | Patients with chronic conditions (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular conditions, bronchial asthma) | 90 | India | Cross-sectional | Pill count | Prescribed doses taken | 92.29% ± 4.5% for counseled group |

| Self-assessment | Rating system | 84.71% ± 11.8% for usual care | |||||

| Hashmi et al[12] | Patients prescribed anti-hypertensive medication for at least 1-mo prior | 438 | Pakistan | Cross-sectional | Pill count | ≥ 80% pills taken | Pill count : 77% |

| 4-item MMAS | ≥ 0 scores | Morisky: Mean overall score = 2.5 ± 1.3 | |||||

| Qureshi et al[29] | Patients on anti-hypertensive medications | 178 | Pakistan | Randomized controlled trial | MEMS bottles | Prescribed doses taken | Intervention arm: 48.1%, 95%CI: 35.8%-60.4% |

| Control arm: 32.4%, 95%CI: 22.6%-42.3% | |||||||

| Kar et al[30] | Adults with SBP ≥ 140 | 1010 | India | Cross-sectional | Self-report | All prescribed doses taken daily in the past 15 d | Baseline: 37.9% |

| Follow-up: 58.3% | |||||||

| Bahl et al[26] | Adults with hypertension | 1175 | India | Prospective | Self-report | If all doses were taken since last visit | 100% at each follow-up point |

| Palanisamy et al[31] | Post discharge patients prescribed at least 1 anti-hypertensive medication | 43 | India | Cross-sectional | 4-item MMAS | At least 1 yes response was classified as non-adherent | 95.4% |

| Dennis et al[19] | Hypertensive adults with at least 6 mo treatment history | 608 | India | Cross-sectional | BMQ | ≥ 1 indicates non-adherence | 50.33% |

| Saleem et al[21,22] | Hypertension adults using anti-hypertensive drugs for last 6 mo | 385 | Pakistan | Cross-sectional | DAI-10 | ≥ 0 survey scores | Overall mean score: -1.74 ± 2.154 |

| Soliman et al[27] | Adults with an estimated 10-yr total CVD risk score greater than 20% | 203 | Sri Lanka | Randomized clinical trial | Pill count | Not reported | Intervention arm: Over 80% with > 80% pill compliance |

| Usual care arm: Results not provided | |||||||

| Simkhada[16] | Hypertensive patients taking anti-hypertensive medication for at least 6 mo | 147 | Nepal | Cross-sectional, prospective study | 6-item questionnaire | ≤ 1 scores | 17.34% |

| Fathima et al[13] | Patients at a CVD clinic | 162 | India | Cross-sectional | 4-item MMAS | ≥ 0 scores | Mean score = 3.2 |

| Thom et al[28] | Adults with established CVD, or estimated 5-yr CVD risk ≥ 15% | 2004 | Europe and India | Randomized clinical trial | Self-report | Taking medication at least 4 d during the week preceding visit | Intervention arm: 86.3% |

| Usual care arm: 64.7% | |||||||

| Khanam et al[23] | Randomly selected hypertensive adults from 3 rural surveillance sites | 29960 | Bangladesh | Cross-sectional | Self-report | Continued medication use at time of interview | 73.8% |

| Kumar et al[15] | Adults on anti-hypertensive medication for more than 6 mo | 120 | India | Cross-sectional | 8-item MMAS | ≤ 2 scores | 54.2% |

| Self-reporting | Not-defined in paper | 96.7% | |||||

| Rao et al[24] | Adults with hypertension and/or diabetes | 426 | India | Cross-sectional | Self-report | ≥ 80% pills taken | Hypertensive 82.2% |

| Diabetic 83.6% | |||||||

| Venkatachalam et al[14] | Adults with hypertension for ≥ 1 yr | 473 | India | Cross-sectional | 4-item MMAS | ≥ 0 scores | 24.1% |

MMAS: Morisky medication adherence scale; MEMS: Medication event monitoring system; SBP: Systolic blood pressure; CVD: Cardiovascular disease; BMQ: Brief medication questionnaire; DAI: Drug attitude inventory.

The majority of the studies included in this review were conducted in India (n = 11). The remainder of the studies were conducted in Pakistan (n = 3), Bangladesh (n = 1), Nepal (n = 1) and Sri Lanka (n = 1). Below, we provide a synthesis of these results in terms of strategies used to measure adherence followed by interventions to improve adherence to CVD medications in South Asian populations.

Adherence assessments

Adherence is defined as “the extent to which a person’s behaviour - taking medication, following a diet, and/or executing lifestyle changes, corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health care provider”[10]. Of the 17 publications included in this review, 10 focused on assessing adherence to CVD medications. Adherence was defined and measured using a variety of methods across studies. These studies largely used self-report to determine adherence rate, including the use of the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS)[11] and other validated questionnaires, interview questions and pill counts.

Five studies used the validated MMAS[11] as their primary method of adherence assessment. These studies utilized the 4-item MMAS, which scores 1 point for each “no” response and 0 points for each “yes” response, with total scores ranging from 0 (non-adherent) to 4 (fully adherent). Hashmi et al[12] used the 4-item MMAS to evaluate adherence to anti-hypertensive therapy in 460 patients from two tertiary care hospitals in Pakistan. Additionally, patients were asked to report the number of pills they were prescribed each week and the number of pills they took and missed over the previous 3, 5, and 7 d. Adherence rate was calculated as pills taken divided by pills prescribed for each time point, with patients taking 80% or more of their prescribed medication classified as adherent, and those taking less than 80% classified as non-adherent. According to the 80% cutoff level, 77% of patients were adherent (mean = 98% ± 5%) and 23% were non-adherent (mean = 39% ± 29%). The mean overall MMAS score was 2.5. Results indicated that adherence by pill count was significantly associated with MMAS score (β = 0.016 for the linear relationship between pill count and MMAS; P < 0.001). Fathima et al[13] used the 4-item MMAS to evaluate adherence to prescribed medications among 162 patients with hypertension, diabetes or ischemic heart disease in Bangalore, India. Total scores ranged from 0 (non-adherent) to 4 (fully adherent), with scores of 1, 2, and 3 classified as moderately adherent. The mean MMAS score was 3.2, with 40.1% classified as fully adherent, 58.6% classified as partially adherent, and 1.3% classified as non-adherent. Results showed a significant association between age and adherence, with a significantly higher proportion of patients 60 years of age and older fully adherent (48.1%) compared to those under 60 (32.5%), P < 0.05. Similarly, a significantly higher proportion of patients who perceived that their medication was not expensive were fully adherent (51.2%) compared to those who perceived their medication as expensive (27.6%), P < 0.05. Venkatachalam et al[14] examined determinants of adherence to hypertension medication in 473 individuals residing in South India. Adherence was assessed using the 4-item MMAS, where patients were classified as non-adherent if they failed to meet any one of the four MMAS criteria. Overall adherence was 24.1%, with 51.6% of patients forgetting to take medication regularly, 59.8% having difficulty remembering to take their medication, 53.6% stopping medication upon feeling better, and 55.2% stopping medication upon feeling worse. Kumar et al[15] looked at factors associated with medication adherence in 120 hypertensive patients at a tertiary care hospital in India. Adherence was assessed using the 8-item MMAS and through self-report (not well defined in the publication). The 8-item MMAS was scored 1 point for every “yes” response and 0 points for every “no” response, with a score of 2 or greater classified as low adherence, 1-2 as medium adherence, and 0 as high adherence. Despite a self-reported adherence rate of 96.7%, MMAS scores indicated that 45.8% of the study sample had low adherence, 54.2% had medium adherence, and 0% had high adherence.

Simkhada[16] conducted a cross-sectional prospective study of blood pressure control and predictors among 147 hypertensive patients in Nepal. Adherence was assessed using a 6-item questionnaire adapted from Choo et al[17] and Morisky et al[11] as used by Rose et al[18] in a previous publication. The 6 questions assessed difficulty taking medications, forgetting to take medications, number of days medications were missed in the past week, number of days an extra pill was taken in the past week, medications taken less because the patient felt better, and medications taken more because the patient felt worse. Patients who responded “yes” to two or more questions were classified as non-adherent. Results showed that only 29.9% of patients were adherent to blood pressure medications.

Two studies included in this review used validated questionnaires other than the MMAS to assess adherence. Dennis et al[19] examined barriers to medication adherence in 608 hypertensive patients in India. Adherence was measured using the Brief Medication Questionnaire (BMQ), and through detailed patient interviews. The BMQ is a self-reported survey that measures barriers to adherence through four screens. The regimen screen (previously validated against Medication Event Monitoring System caps)[20] consists of 5 questions assessing patient behavior towards taking medication. Each question is worth 1 point, where scores greater than 1 indicate non-adherence. Overall, 50.3% of patients were adherent to anti-hypertensive therapy. Many patients believed that either their medications were not working (37.8%), or that medications would bother them (5.9%). Access to medication was also an issue, with 78.6% of patients reporting difficulty paying for medication and 54.9% reporting difficulty getting refills on time.

Saleem et al[21] examined the association between knowledge and medication adherence among 385 hypertensive patients in Quetta City, Pakistan. Adherence was measured using the 10-item drug attitude inventory (DAI-10). Scores ranged from -10 to 10, with negative scores indicating non-adherence, 0-5 indicating moderate adherence, and 6-10 indicating high adherence. The DAI-10 was pilot-tested with 40 hypertensive patients for reliability and validity (Cronbach’s α = 0.7) and translated from English to Urdu. The hypertension fact questionnaire was used to assess patient’s knowledge of hypertension, its causes, treatment and management. The overall mean score of the DAI-10 was -1.74 ± 2.15. In this study, 64.7% of patients were classified as non-adherent, 35.3% as moderately adherent, and none as highly adherent. There was a significant, inverse relationship between knowledge and adherence, which investigators noted was a conflicting outcome. Saleem et al[22] published another study on the same population, using the same assessment of adherence, looking at the association between adherence and quality of life. These results showed no relationship between quality of life and medication adherence.

Two of the included studies used interview questions to assess adherence. Khanam et al[23] measured adherence to anti-hypertensive medication in 29960 patients residing in rural Bangladesh. Adherence was measured through self-reported interview questions using a two-part questionnaire on chronic disease lifestyle risk factors and management. The questionnaire was translated from Bangla to English and back in order to check for consistency of the meaning. Additionally, the questionnaire was piloted and pre-tested. Non-adherence was defined as discontinuation of medication at the time of the interview and was classified as a dichotomous various variable (yes or no) based on this definition. The overall rate of non-adherence in this population was 26.2%. Non-adherence was higher among men (29.2%) than women (24.3%), (P < 0.001), decreased with age (P < 0.001) and was less common among wealthy people. Non-adherence was greater when hypertension was diagnosed by unqualified providers (community health workers or informal health providers) (OR = 1.67, 95%CI: 1.42-1.97). Those who reported cardiovascular comorbidities (angina, heart attack or stroke) were more likely to be adherent to medication (OR = 0.78, 95%CI: 0.64-0.97 for non-adherence). Rao et al[24] examined medication adherence among 426 patients with either hypertension or type-2 diabetes mellitus in southern India. Adherence to either hypertension or diabetes medication was assessed through self-reported interview questions. Patients were asked to report how they had been taking their medication in the week preceding the interview. Patients who reported taking less than 80% of their prescribed medications in the week preceding the interview were classified as non-adherent. The interview questions were pilot tested and the validity was appraised by experts. Among hypertensive patients, 82.2% reported adherence to treatment, while 83.6% of diabetics reported adherence to treatment. Adherence was higher among females (87.4%) than males (72.2%) (P < 0.05). High cost of treatment and asymptomatic disease were the most commonly cited reasons for non-adherence among those with hypertension (39% and 35% respectively) and diabetes (30% and 48%, respectively).

Joshi et al[25] examined the relationship between medication adherence and blood pressure control in 156 hypertensive patients in urban India. Adherence was assessed at the end of three month follow-up by pill count. Subjects who took less than 80% of their medication were classified as non-adherent. Adherence was 79% among patients with controlled hypertension, and 39% among patients with uncontrolled hypertension. Additionally, non-adherence was a significant predictor of uncontrolled hypertension in this population (OR = 6.23, 95%CI: 2.36-16.48, P > 0.0001).

Strategies for improving adherence

Of the 17 publications included in this review, 7 publications examined interventions aimed at improving adherence to CVD medications in South Asian populations as a primary or secondary outcome. Three of these interventions examined the use of combination or polypill therapy to improve adherence. Bahl et al[26] conducted an observational, open-label study to examine the use of a fixed combination therapy of perindopril and amlodipine on the management of hypertension among 1250 patients in India. Adherence was measured via self-report through interview questions asked on days 15, 30 and 60 of follow-up. Patients were asked if they had missed any doses and what time they took their medication the day prior to follow-up. All patients who completed the study (94%) adhered to their treatment as specified in the study protocol. It is important to note that there was no usual care group in this study. It is also important to point out that this is a clinical trial, in which participants are generally more adherent than free-living populations. Soliman et al[27] examined the effects of a polypill (75 mg aspirin, 20 mg simvastatin, 10 mg Lisinopril and 12.5 mg hydrochlorothiazide) vs usual care (not specified) on the prevention of CVD in 216 patients without established CVD. Adherence was assessed via monthly self-reports using pill counts (no further details provided). Results showed that the polypill intervention arm had 80% of patients with greater than 80% adherence, 6% with 60%-79% adherence, 3% with 40%-59% adherence, and 10% with < 40% adherence. Results for the usual care group were not reported. Thom et al[28] studied the effects of a fixed-dose combination (FDC) therapy (either aspirin, 75 mg; simvastatin, 40 mg; lisinopril, 10 mg; and atenolol, 50 mg or aspirin, 75 mg; simvastatin, 40 mg; lisinopril, 10 mg; and hydrochlorothiazide, 12.5 mg) vs usual care (treated at the discretion of their usual physician) on medication adherence and risk factors in patients at high risk of CVD. They utilized data from the Use of a Multidrug Pill in Reducing Cardiovascular Events randomized clinical trial of 1004 patients from Europe, and 1000 from India. Adherence was measured through self-report during a follow-up visit and defined as taking medication at least 4 d during the week before the visit. For patients in India, adherence in the FDC group vs the usual care group was 89.1% and 63.6%, respectively (RR = 1.40; 95%CI: 1.30-1.51). For patients in Europe, adherence in the FDC group vs the usual care group was 83.6% and 65.8%, respectively (RR = 1.27; 95%CI: 1.18-1.37). The effects of the FDC strategy on adherence did not differ significantly between patients from India vs patients from Europe (P = 0.07 for interaction).

Qureshi et al[29] used MEMS bottles to determine the impact of an education package aimed at general practitioners to increase adherence to anti-hypertensive drugs in 200 patients in Karachi, Pakistan. Components of the education package included non-pharmacological (diet, exercise, weight loss, smoking cessation) and pharmacological interventions (prescribing low cost and appropriate generic drugs; preferential use of single dose drug regimens; scheduled follow-up visits; stepped care approach for titration of drugs to achieve target blood pressure levels; and satisfactory consultation sessions for patients, with explanations of treatment and use of appropriate communication strategies). Adherence, defined as percentage of prescribed doses taken, was measured using MEMS bottles, which electronically monitored and recorded the time each cap was opened. Adherence was recorded by community health workers at the end of weeks 1, 3 and 6 of the study. Adherence was significantly better in the intervention group (unadjusted mean percentage days with correct dose) vs the standard of care group (48.1% vs 32.4%, P = 0.048) over the 6 wk period. Greater adherence was significantly associated with higher levels of education (P < 0.001), patients being encouraged by family members to take medications (P < 0.001), patient’s belief in drug effects (P < 0.001) and having the purpose of the drug explained to the patient (P < 0.001).

Three small scale interventions used counseling to improve adherence. Kar et al[30] conducted a community intervention to implement the World Health Organization (WHO) CVD risk management package in India. The intervention was implemented among 1010 adults from a randomly chosen cluster of households, and 79 hypertensive patients were followed at 1, 3, and 5 mo to reinforce risk prevention and adherence to medications. Adherence was assessed by self-report and defined as daily intake of all prescribed anti-hypertensive medication in the past 15 d. In the intervention households, regular intake of medication increased from 37.9% to 58.3% (P < 0.05), while in the control households, it decreased from 43.5% to 34.8%. Palanisamy et al[31] conducted a non-randomized intervention to improve adherence among 43 post discharge hypertensive patients in India, and analyzed differences in adherence pre and post intervention. After discharge, patients were given counseling on drugs and lifestyle modification, were provided with a medication schedule reminder and received frequent telephone reminders from study pharmacists. Adherence was assessed using a version of the Morisky scale, which included a 5-point response option (never/rarely/sometimes/often/always) and a set of open-ended questions regarding reasons for non-adherence. Scores ranged from 0-4 for the response option questions and 0-16 for the open-ended questions, with higher scores indicating poorer adherence. All patients who answered “yes” to at least one question were considered non-adherent. At baseline, 100% of the patients were considered non-adherent, whereas at the second interview, 51.2% were non-adherent and at the third interview, only 4.6% were non-adherent. Ponnusankar et al[32] conducted a randomized study of 90 patients with chronic conditions to assess the impact of patient medication counseling on adherence. Patients in the intervention group received a 15-20 min medication counseling session from a pharmacist. In order to determine adherence, patients were asked to bring back all remaining medications and empty foils along with medication receipts, as well as to complete an adherence self-assessment form. As measured by pill count at follow-up, adherence was 92.2% ± 4.5% for counseled group and 84.7% ± 11.8% for the usual care group. As measured by the self-assessment form, 75% of patients in the intervention group and 67% of patients in the usual care group rated themselves as adherent.

Two additional interventions were identified, however, only the design/rationale papers have been published at this point. Fathima et al[33] reported the design of the Primary pREvention strategies at community level to Promote Adherence of treatment to pREvent cardiovascular diseases (PrePare) study, a multi-center, household-level, cluster-randomized trial to improve systolic blood pressure (BP) and medication adherence in at-risk households in India. The intervention consists of household visits by community health workers (CHWs) every two months. The CHWs will assess adherence by administering a questionnaire and inspecting the empty blister packets or purchase receipts, measure BP and ascertain if BP values meet the preset targets, ensure that individuals adhere to the prescribed treatment by using educational messages to target tobacco use, adherence to medication, and promote lifestyle changes and set goals for BP and weight and reduction in tobacco use and weight reduction goals for the next visit. Kamath et al[34] reported the design of the Secondary Prevention of Acute Coronary Syndromes study, a hospital-based, open-label, randomized trial of community health worker interventions vs usual care in India. The intervention includes a patient diary with information on ischemic heart disease risk factors, treatments and importance of treatment compliance, as well as calendar checklist, on which patients mark every time they take a dose of their medications. Adherence will be calculated based on the percentage of doses taken of those prescribed. The 4-item MMAS will also be used to assess adherence at follow-up visits. If patients prematurely stopped taking their medications, the reasons for doing so will be elicited.

DISCUSSION

In this systematic review, we provide a summary of the methodologies used to assess and interventions to improve adherence to CVD medications in South Asians. The most common method for assessing adherence was patient self-report (n = 16). While self-reporting does open the door to recall bias, it provides one of the most economically feasible methods for data collection. All of these studies were conducted in developing countries or in resource limited settings, which could be a contributing factor to the use of self-report rather than “gold standard” methods such as MEMS caps or pharmacy refill data. Usage of MEMS caps in resource-limited settings is most likely constrained due to their high costs (approximately $100 USD per cap)[35-37]. Only 1 study in our review included the use of MEMS caps, in a region where the gross national income per capita is $1483 USD, which is the lowest in the world[38]. As expected, pharmacy refill data, which relies on complete pharmacy records, was not used by any of the included studies. Without reliable and interoperable electronic pharmacy records, tracking where patients get their medication from can prove to be largely difficult and resource intensive.

In addition to primarily relying on self-report, several of the studies did not use validated instruments. Of the 16 studies using self-reported measures, 7 used validated questionnaires, while 9 studies used non-validated interview or survey questions. Furthermore, there was a general lack of information on these interview or survey questions. Details on how adherence rates were calculated or how data was collected were missing in several of these publications. There was also a general lack of detail on what class and type of medications was being measured for adherence. From the studies that did report medication type, the majority were anti-hypertensive medications. There was little data on other CVD medications such as anti-platelets and cholesterol lowering medications.

It is important to note that the adherence rates from non-validated, self-reported interview or survey questions were typically higher than those of the validated scale measurements. The most glaring of disparities appears in Kumar et al[16] where 96.7% of patients were classified as adherent according to a self-report assessment form and only 54.2% of patients were classified as medium adherent and 0% classified as highly adherent according to the 8-item MMAS. Therefore, researchers in this region should consider using validated measures such as the MMAS as opposed to non-validated measures when assessing adherence. Additionally, several of these papers did not assess whether a higher medication adherence to hypertensive medications was associated with an improvement in an intermediate outcome measure such as blood pressure control. Generally the adherence rates were low which shows a growing need for future interventions geared towards improving adherence.

Overall, very few studies (n = 7) evaluated the impact of interventions to improve adherence. One intervention targeted provider education. While important, provider based interventions are typically considered quality improvement and are generally considered weak interventions[39]. Three interventions focused on the use of allied health care providers, such as community health workers or pharmacists, to educate or counsel patients on the importance of adhering to medication. Two of these interventions provided drug counseling from pharmacists to patients in an attempt to improve medication adherence, and both showed promising results. The third followed the WHO CVD risk management package utilizing community health care workers to assess risk and provide counseling on lifestyle changes to manage that risk. Community health care workers are a unique resource available to most if not all of these countries and could form the backbone for interventions directed at improving medication adherence in these low resource environments. The final 3 interventions were geared towards reducing pill burden through the use of polypills. No interventions targeted patient-provider communication, which may be an important determinant of a patient’s medication adherence[40].

An important distinction to note is that non-adherence can be classified as either (1) intentional; or (2) unintentional. Intentional non-adherence is related to patient’s beliefs and knowledge and health seeking behaviors, while unintentional non-adherence is related to demographics and comorbid illness[41]. Unintentional and intentional non-adherence to medications are related to different patient characteristics. A review of medication adherence in native and immigrant South Asians noted that the primary factors related to non-adherence in the included studies were forgetfulness, side-effects and choosing not to take the medication[42]. This suggests that both unintentional and intentional nonadherence contribute to overall non-adherence in South Asian populations and successful interventions aimed at improving adherence in this population should address both mechanisms. The interventions included in this review did not make such a distinction, and thus the generalizability of the results is limited.

Several studies cited behavioral barriers to medication adherence. Interventions geared towards patient education could improve patient self-efficacy and help break down these barriers. Additionally, there was a general lack of system-wide interventions such as audit and feedback and decision support systems. Although the lack of electronic medical record data in this region would lead to a low overall yield for decision support systems. However, audit and feedback interventions could be utilized more in resource constrained settings. Furthermore, we found a lack of interventions utilizing technology to assist patient adherence. Several of these regions benefit from a high cell phone density[43]. However, none of the interventions included in this review used cell phone reminders through text messages or other means to improve medication adherence. Although most interventions used in these studies showed promising results, further research is needed to determine which interventions or combination of interventions is the most effective strategy for improving medication adherence in this resource constrained environment. This research along with cost-effectiveness of each of the above mentioned strategies would be informative as policy makers decide which of these interventions could be scaled up to the population level.

In conclusion, we found that self-report measures were the most commonly used method to assess adherence. Although several interventions were directed towards providers, allied health care professionals and community health care workers, there is a need to employ strategies directed towards provider-patient communication. Additionally, there is a need to better incorporate technology such as cell phones, which are readily available for most people living in these countries. Examples of this type of intervention include the use of tailored and specific Short Text Message (SMS) reminders to improve medication adherence[44] and the use of text and a voice SMS in local language to improve health literacy and medication adherence[45].

Future research should focus on using more validated self-reported measurements. These scales should be validated in South Asian populations specifically, since health literacy may vary from previously studied populations. Additionally, there is a need to tie these adherence measurements to intermediate outcome measures such as blood pressure or cholesterol control as well as determine their effects on CVD outcomes.

COMMENTS

Background

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide, with an estimated 17.5 million people dying from CVD in 2012. Approximately one-fifth of the global population resides in South Asia, where patients suffer from a disproportionately high rate of CVD-related morbidity and mortality. Adherence to medication is critical to the effectiveness of CVD risk management. Therefore, the aim of this review is to examine current methods of assessing adherence and strategies to improve adherence to CVD medications, among South Asian CVD patients.

Research frontiers

Current research indicates a growing epidemic of premature CVD in South Asian populations. Establishing suitable strategies to assess adherence to CVD medications is of particular importance to South Asian countries for various reasons. First, low availability of electronic medical records in most health care settings precludes accurate assessment of medication adherence using electronic medication refill data by health care providers. Second, the overall health literacy and the opportunities to improve provider and patient awareness of the importance of medication adherence may be limited. Lastly, low availability of pharmacy records and medication refill data also limit the use of traditional measures used to assess medication adherence.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Understanding adherence to CVD medications in South Asian populations is an important research question. This study focuses on the specific challenges and complexities related to CVD medication adherence in native South Asians.

Applications

This review demonstrates the need to identify a gold standard for assessment of adherence related to CVD medications in South Asians. Additionally, there is a need to employ intervention strategies directed towards provider-patient communication and to tie these interventions to intermediate outcome measures in order to determine their effects on CVD outcomes.

Terminology

Adherence in this review is defined as “the extent to which a person’s behaviour - taking medication, following a diet, and/or executing lifestyle changes, corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health care provider”. The Morisky Medication Adherence Scale is a 4 or 8-item self-report questionnaire that results in a score ranging from 0 (non-adherent) to 4 or 8 (fully adherent).

Peer-review

In this manuscript, Virani et al reviewed mainly adherence to antihypertensives in South Asian populations and the methodology of studies conducted in this field. It is an interesting topic and the presentation of data is impressive.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Hatipoglu S, Presutti DG S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

Supported by American Heart Association Beginning Grant-in-Aid, No. 14BGIA20460366; the American Diabetes Association Clinical Science and Epidemiology award (1-14-CE-44); the Baylor College of Medicine Center for Globalization Award; and the Houston VA HSR&D Center for Innovations grant, No. HFP 90-020.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available other than articles cited in this review.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: June 2, 2015

First decision: July 3, 2015

Article in press: September 30, 2015

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). [Accessed 2015 Apr 15] Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reddy KS, Yusuf S. Emerging epidemic of cardiovascular disease in developing countries. Circulation. 1998;97:596–601. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.6.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ounpuu S, Anand S. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: part I: general considerations, the epidemiologic transition, risk factors, and impact of urbanization. Circulation. 2001;104:2746–2753. doi: 10.1161/hc4601.099487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reddy KS. Cardiovascular disease in non-Western countries. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2438–2440. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joshi P, Islam S, Pais P, Reddy S, Dorairaj P, Kazmi K, Pandey MR, Haque S, Mendis S, Rangarajan S, et al. Risk factors for early myocardial infarction in South Asians compared with individuals in other countries. JAMA. 2007;297:286–294. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaziano TA, Bitton A, Anand S, Abrahams-Gessel S, Murphy A. Growing epidemic of coronary heart disease in low- and middle-income countries. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2010;35:72–115. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yusuf S, Islam S, Chow CK, Rangarajan S, Dagenais G, Diaz R, Gupta R, Kelishadi R, Iqbal R, Avezum A, et al. Use of secondary prevention drugs for cardiovascular disease in the community in high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (the PURE Study): a prospective epidemiological survey. Lancet. 2011;378:1231–1243. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61215-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown MT, Bussell JK. Medication adherence: WHO cares? Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86:304–314. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumbhani DJ, Steg PG, Cannon CP, Eagle KA, Smith SC, Hoffman E, Goto S, Ohman EM, Bhatt DL. Adherence to secondary prevention medications and four-year outcomes in outpatients with atherosclerosis. Am J Med. 2013;126:693–700.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Switzerland: Geneva; 2003. Available from: http://www.who.int/chronic_conditions/adherencereport/en. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986;24:67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashmi SK, Afridi MB, Abbas K, Sajwani RA, Saleheen D, Frossard PM, Ishaq M, Ambreen A, Ahmad U. Factors associated with adherence to anti-hypertensive treatment in Pakistan. PLoS One. 2007;2:e280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fathima FN, Shanbhag DN, Hegde SKB, Sebastian B, Briguglio S. Cross Sectional Study of Adherence to Prescribed Medications among Individuals Registered at a High Risk Clinic in a Rural Area in Bangalore, India. Indian J Publ Health Research and Development. 2013;4:90–93. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Venkatachalam J, Abrahm SB, Singh Z, Stalin P, Sathya GR. Determinants of Patient’s Adherence to Hypertension Medications in a Rural Population of Kancheepuram District in Tamil Nadu, South India. Indian J Community Med. 2015;40:33–37. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.149267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar N, Unnikrishnan B, Thapar R, Mithra P, Kulkarni V, Holla R, Bhagawan D, Mehta I. Factors associated with adherence to antihypertensive treatment among patients attention a tertiary care hospital in Mangalore, South India. IJCRR. 2014;6:77–85. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simkhada R. Study on blood pressure control status and predictors of uncontrolled blood pressure among hypertensive patients under medication. Nepal Med Coll J. 2012;14:56–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choo PW, Rand CS, Inui TS, Lee ML, Cain E, Cordeiro-Breault M, Canning C, Platt R. Validation of patient reports, automated pharmacy records, and pill counts with electronic monitoring of adherence to antihypertensive therapy. Med Care. 1999;37:846–857. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199909000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rose AJ, Berlowitz DR, Orner MB, Kressin NR. Understanding uncontrolled hypertension: is it the patient or the provider? J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2007;9:937–943. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2007.07332.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dennis T, Meera NK, Binny K, Sonal Sekha M, Kishorea G, Sasidharanc S. Medication adherence and associated barriers in hypertension management in India. CVD Prev Control. 2011;6:9–13. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Svarstad BL, Chewning BA, Sleath BL, Claesson C. The Brief Medication Questionnaire: a tool for screening patient adherence and barriers to adherence. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;37:113–124. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saleem F, Hassali MA, Shafie AA, Awad AG, Bashir S. Association between knowledge and drug adherence in patients with hypertension in Quetta, Pakistan. Trop J Pharma Res. 2011;10:125–132. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saleem F, Hassali MA, Shafie AA, Awad GA, Atif M, ul Haq N, Aljadhey H, Farooqui M. Does treatment adherence correlates with health related quality of life? Findings from a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:318. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khanam MA, Lindeboom W, Koehlmoos TL, Alam DS, Niessen L, Milton AH. Hypertension: adherence to treatment in rural Bangladesh--findings from a population-based study. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:25028. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.25028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rao CR, Kamath VG, Shetty A, Kamath A. Treatment Compliance among Patients with Hypertension and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in a Coastal Population of Southern India. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5:992–998. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joshi PP, Salkar RG, Heller RF. Determinants of poor blood pressure control in urban hypertensives of central India. J Hum Hypertens. 1996;10:299–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bahl VK, Jadhav UM, Thacker HP. Management of hypertension with the fixed combination of perindopril and amlodipine in daily clinical practice: results from the STRONG prospective, observational, multicenter study. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2009;9:135–142. doi: 10.1007/BF03256570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soliman EZ, Mendis S, Dissanayake WP, Somasundaram NP, Gunaratne PS, Jayasingne IK, Furberg CD. A Polypill for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a feasibility study of the World Health Organization. Trials. 2011;12:3. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thom S, Poulter N, Field J, Patel A, Prabhakaran D, Stanton A, Grobbee DE, Bots ML, Reddy KS, Cidambi R, et al. Effects of a fixed-dose combination strategy on adherence and risk factors in patients with or at high risk of CVD: the UMPIRE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:918–929. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.277064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qureshi NN, Hatcher J, Chaturvedi N, Jafar TH. Effect of general practitioner education on adherence to antihypertensive drugs: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2007;335:1030. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39360.617986.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kar SS, Thakur JS, Jain S, Kumar R. Cardiovascular disease risk management in a primary health care setting of north India. Indian Heart J. 2008;60:19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palanisamy S, Sumathy A. Intervention to improve patient adherence with antihypertensive medications at a tertiary care teaching hospital. Int J PharaTech Res. 2009;1:369–374. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ponnusankar S, Surulivelrajan M, Anandamoorthy N, Suresh B. Assessment of impact of medication counseling on patients’ medication knowledge and compliance in an outpatient clinic in South India. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;54:55–60. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fathima FN, Joshi R, Agrawal T, Hegde S, Xavier D, Misquith D, Chidambaram N, Kalantri SP, Chow C, Islam S, et al. Rationale and design of the Primary pREvention strategies at the community level to Promote Adherence of treatments to pREvent cardiovascular diseases trial number (CTRI/2012/09/002981) Am Heart J. 2013;166:4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kamath DY, Xavier D, Gupta R, Devereaux PJ, Sigamani A, Hussain T, Umesh S, Xavier F, Girish P, George N, et al. Rationale and design of a randomized controlled trial evaluating community health worker-based interventions for the secondary prevention of acute coronary syndromes in India (SPREAD) Am Heart J. 2014;168:690–697. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ailinger RL, Black PL, Lima-Garcia N. Use of electronic monitoring in clinical nursing research. Clin Nurs Res. 2008;17:89–97. doi: 10.1177/1054773808316941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.List of adherence aids. [Accessed 2015 May 27] Available from: http://www.ncpanet.org/pdf/adherence/adherence_aids.pdf.

- 37.Journal of Clinical Research Best Practices. [Accessed 2015 May 26] Available from: https://firstclinical.com/journal/2007/0708_Pill_Bottles.pdf.

- 38.Economy and Growth. [Accessed 2015 May 26] Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/topic/economy-and-growth.

- 39.Grol R, Wensing M, Eccles M. Improving Patient Care: The Implementation of Change in Clinical Practice Edinburgh. Scotland: Elsevier; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zolnierek KB, Dimatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47:826–834. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5acc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wroe AL. Intentional and unintentional nonadherence: a study of decision making. J Behav Med. 2002;25:355–372. doi: 10.1023/a:1015866415552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ens TA, Seneviratne CC, Jones C, Green TL, King-Shier KM. South Asians’ cardiac medication adherence. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014;13:357–368. doi: 10.1177/1474515113498187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mobile Cellular Subscriptions (per 100 People). [Accessed 2015 May 18] Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.CEL.SETS.P2.

- 44.Improving Medication Adherence Through SMS (Short Messaging Service) in Adult Stroke Patients: a Randomised Controlled Behaviour Intervention Trial. [Accessed 2015 May 26] Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01986023?term=SMSfor stroke&rank=1.

- 45.Using a Tailored Health Information Technology Driven Intervention to Improve Health Literacy and Medication Adherence (TalkingRx). [Accessed 2015 May 26] Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02354040?term=NCT02354040&rank=1.