SUMMARY

MazF is an mRNA interferase, which, upon activation during stress conditions, cleaves mRNAs in a sequence-specific manner, resulting in cellular growth arrest. During normal growth conditions, the MazF toxin is inactivated through binding to its cognate antitoxin, MazE. How MazF specifically recognizes its mRNA target and carries out cleavage and how the formation of the MazE-MazF complex inactivates MazF remain unclear. We present crystal structures of MazF in complex with mRNA substrate and antitoxin MazE in Bacillus subtilis. The structure of MazF in complex with uncleavable UUdUACAUAA RNA substrate defines the molecular basis underlying the sequence-specific recognition of UACAU and the role of residues involved in the cleavage through site-specific mutational studies. The structure of the heterohexameric (MazF)2-(MazE)2-(MazF)2 complex in Bacillus subtilis, supplemented by mutational data, demonstrates that the positioning of the C-terminal helical segment of MazE within the RNA-binding channel of the MazF dimer prevents mRNA binding and cleavage by MazF.

INTRODUCTION

Toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems are found in plasmids and chromosomes of bacteria and archaea. Plasmid-encoded TA systems have been shown to play a role in the maintenance of plasmids, whereas chromosomally encoded TA systems have been shown to be involved in the regulation of cell growth, thus promoting cellular adaptation in an ever-changing environment (Yamaguchi et al., 2011). TA systems usually consist of an operon that encodes a stable toxin and an unstable antitoxin. In normally growing cells, the antitoxin forms a stable complex with toxin and, thus, prevents it from attacking cellular targets. Under stress conditions, labile antitoxins are readily degraded by cellular proteases, resulting in active toxin capable of exerting its toxic effect (Buts et al., 2005; Gerdes et al., 2005; Yamaguchi and Inouye, 2011). Some kinds of antitoxins, aside from binding to their cognate toxin molecules and preventing them from attacking cellular targets, also contain a DNA binding domain by which they regulate transcription by binding near promoters of the TA operons, typically as TA complexes (Brown et al., 2011; Maté et al., 2012; Mattison et al., 2006; Schumacher et al., 2009).

Since the discovery of first TA system on a plasmid (Ogura and Hiraga, 1983), a number of different TA systems have been identified in various bacterial and archaeal genomes (Yamaguchi et al., 2011). TA systems have been classified into five groups (types I–V) on the basis of the nature of the antitoxin (RNA or protein) and the mechanism of neutralization of the toxin (Schuster and Bertram, 2013). The most extensively studied among these are type II TA systems, in which antitoxins are proteins that inhibit toxin function via protein-protein interactions. The MazE-MazF complex is one of the most well-characterized type II TA systems. MazF, also known as an mRNA interferase, exerts its toxicity by cleaving mRNA in a sequence-specific and ribosome-independent manner (Yamaguchi and Inouye, 2009). Until now, various mRNA interferases and MazF homologs with different mRNA cleavage specificities (spanning three-, five-, or seven-base sequences) have been identified. Escherichia coli MazF specifically cleaves intracellular mRNAs at ACA sequences in order to effectively inhibit protein synthesis and subsequent cell growth (Zhang et al., 2003). Mycobacterium tuberculosis has at least seven MazF homologs, four of which cause growth arrest when induced in E. coli (Zhu et al., 2008; Zhu et al., 2006). E. coli MazF has been shown to cause BCL-2 homologous antagonist/killer (BAK)-dependent programmed cell death when induced in mammalian cells (Shimazu et al., 2007).

Bacillus subtilis also contains a MazE-MazF-like TA system (Pellegrini et al., 2005). Recently, using a 3.5 kb phage MS2 RNA as a substrate, it was shown that B. subtilis MazF is an mRNA interferase that specifically cleaves five-base U^ACAU sequence (^ indicating the cleavage site) (Park et al., 2011). Previous studies using a 375-base mRNA containing the thrS leader region had suggested the consensus cleavage sequence for B. subtilis MazF to be U^AC (Pellegrini et al., 2005). However, the two nucleotides located downstream of this cleavage site in the thrS leader region are AU and, thus, are identical to the pentad U^ACAU sequence mentioned above.

Crystal structures have been determined of MazF from E. coli (Kamada et al., 2003) and B. subtilis (Gogos et al., 2003), and, despite having low sequence homology, they have been shown to fold like CcdB (Loris et al., 1999) and Kid proteins (Hargreaves et al., 2002). Toxin CcdB forms a complex with antitoxin CcdA and targets DNA gyrase A (De Jonge et al., 2009; Maki et al., 1992), whereas Kid toxin forms a complex with antitoxin Kis and cleaves RNA substrates such as MazF (Kamphuis et al., 2007). Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) chemical shift perturbation studies in the presence of an uncleavable substrate, combined with docking calculations, have led to the proposal of putative nucleotide binding sites for Kid and E. coli MazF toxins. In the structural model of the Kid-RNA complex, three residues (Asp75, Arg73, and His17) have been proposed to form the active site of the Kid toxin (Kamphuis et al., 2006). Similar studies on E. coli MazF E24A mutant suggested that the binding of RNA substrate overlaps with the MazE binding site (Li et al., 2006).

Although structures of Kid, E. coli MazF and B. subtilis MazF are known, we still do not know how these MazFs recognize and cleave mRNAs in a sequence-specific manner in the absence of structures of MazF-RNA complexes in these systems. To overcome this limitation, we determined the crystal structure of B. subtilis MazF with uncleavable single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) substrate containing the pentad U^ACAU target sequence, thereby directly providing the structural basis underlying the sequence-specific recognition of RNA substrate by MazF. In addition, structure-guided mutational studies of B. subtilis MazF provided insights into the role of amino acids involved in RNA recognition and catalysis. To elucidate the molecular basis by which the binding of antitoxin MazE prevents toxin MazF from exerting its function, we also solved the structure of MazF in complex with its cognate antitoxin MazE in B. subtilis. Comparison of the structures of MazF-RNA and MazE-MazF complexes provide a direct explanation as to why the MazE-MazF complex is unable to cleave mRNA under normal growth conditions. In the structure of the B. subtilis MazE-MazF complex, the MazE fold is similar to the antitoxin fold observed in CcdA-CcdB (Madl et al., 2006) and ParE-ParD (Dalton and Crosson, 2010) complexes but unlike the E. coli MazE-MazF complex (Kamada et al., 2003), suggestive of potential shuffling of the antitoxin folds between different TA systems.

RESULTS

Choice of mRNA Substrate Constructs and Binding Affinities for B. subtilis MazF

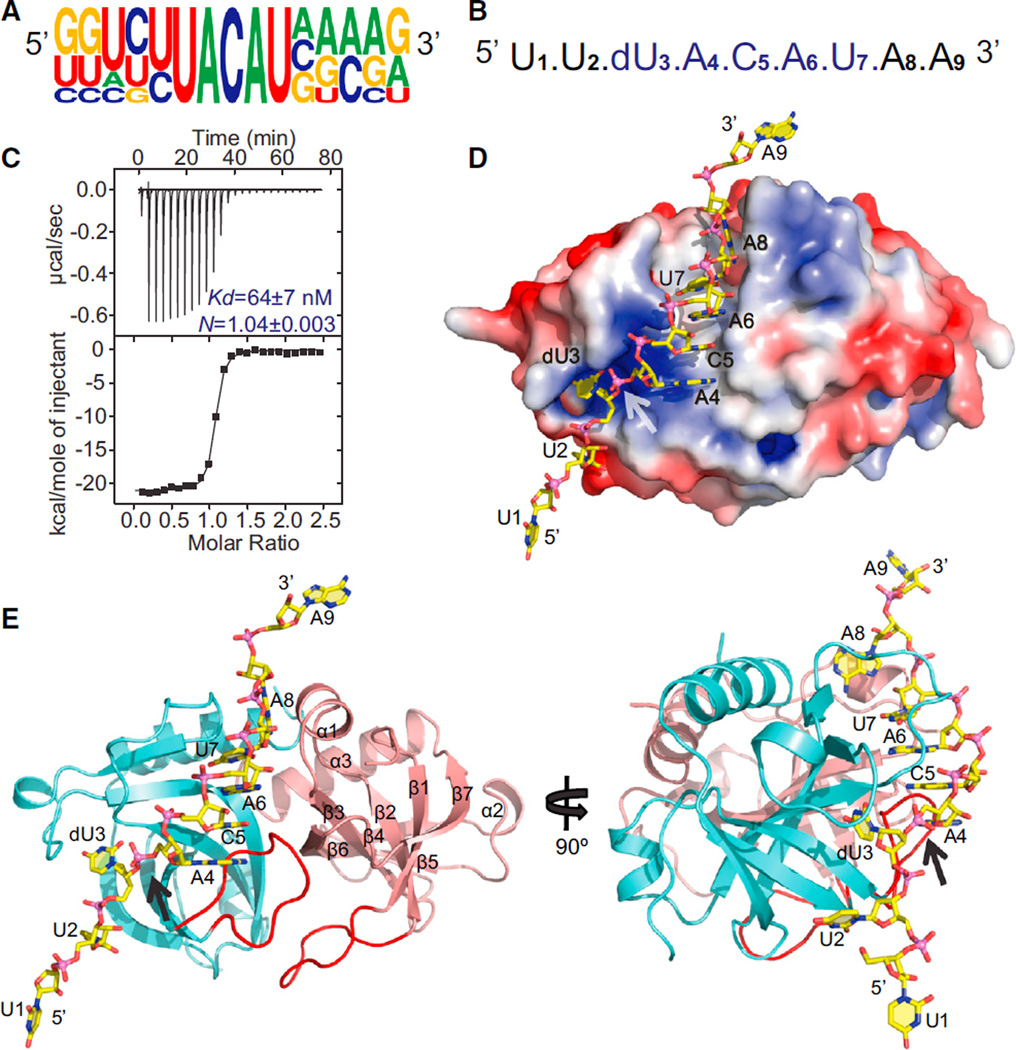

Unlike E. coli MazF, which specifically cleaves intracellular mRNAs at ^ACA and A^CA sites, MazF from B. subtilis has recently been shown to specifically cleave mRNAs between the first uracil and the second adenine within a five-base U^ACAU sequence (Figure 1A), as elucidated with a 3.5 kb phage MS2 RNA as a substrate (Park et al., 2011). For structural studies, we designed ssRNAs of varying length (5- to 9-mers) containing the five-base dU^ACAU cleavage site, the first uracil in the target site being modified to a deoxynucleotide in order to prevent cleavage. Previous studies have shown that the presence of a 2′-OH at the penultimate nucleotide upstream of the cleavage site is essential for the catalytic activity of MazF (Zhang et al., 2005). Our attempt at cocrystallization of B. subtilis MazF with 9-mer U1U2dU3A4C5A6U7A8A9 RNA (Figure 1B) was successful for a sequence that contains two uracil and two adenine nucleotides flanking the 5′ and 3′ of the target pentanucleotide sequence, respectively. In addition, MazF exhibited strong binding affinity (Kd = 64 nM) for this 9-mer RNA when measured with isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) (Figure 1C). The change in enthalpy (−21 kcal per mol) upon ssRNA binding to MazF is a little less than the enthalpy changes observed for RNA recognition motif (RRM)-containing proteins that bind to specific ssRNA (−30 to −60 kcal per mol) (McLaughlin et al., 2011). The N value of ~1 obtained from the ITC experiment suggests that MazF dimer binds to one molecule of ssRNA. Stoichiometric data obtained from the nitrocellulose filter-binding assay also indicate that the MazF dimer binds to ssRNA in a molar ratio of 1:1 (Figure S1A available online).

Figure 1. Binding Affinity and Overall Structure of B. subtilis MazF-RNA Complex Containing UACAU RNA Recognition Element.

(A) Sequence logo plot of multiple sequence alignment of RNA sequences flanking the five different cleavage sites in MS2 RNA by MazF (Park et al., 2011). The height of the nucleotide corresponds to its conservation in the multiple-sequence alignment.

(B) Sequence of the 9-mer RNA containing a dU at the first position of the U^ACAU RNA recognition element used for crystallization.

(C) ITC measurement for binding of uncleavable 9-mer RNA (shown in B) containing UACAU RNA recognition element with MazF. The observed N value of 1.04 reflects 1 RNA bound per MazF dimer.

(D) Electrostatic surface representation of the MazF protein in the MazF-RNA complex. Bound RNA is shown in stick representation and colored yellow. The arrow shows the position of scissile phosphate in the bound RNA.

(E) Two views of the structure of the MazF-RNA complex. The MazF protein is shown in a ribbon representation, whereas the bound RNA (yellow) is shown in a stick representation. Two MazF subunits (cyan and salmon) form a symmetrical dimer. See also Figure S1 and Table S1.

Crystallization and Structure Determination

Crystals of B. subtilis MazF-RNA complex diffracted to high resolution (1.5 Å), and the structure of the complex was determined by molecular replacement with the structure of the apo form of MazF (Protein Data Bank [PDB] ID: 1NE8) (Gogos et al., 2003). The structure of the complex was refined to work R factor = 16.3% and free R = 17.7% with one dimer of MazF bound to one 9-mer ssRNA molecule in the asymmetric unit. Crystallo-graphic data collection and refinement statistics are listed in Table S1. The final refined model of the complex contains well-ordered electron density throughout both protein chains within the dimer (except for the last two amino acids at the C terminus) and includes all nine nucleotides of the bound RNA substrate. An omit map for the bound RNA in the MazF-RNA complex is shown in Figure S1B.

Structure of B. subtilis MazF in Complex with mRNA Substrate

In the B. subtilis MazF-RNA complex structure, one molecule of 9-mer RNA is bound to one MazF dimer (Figures 1D and 1E), and two subunits of MazF form the dimer related by local 2-fold symmetry. Similar to the structure of the apo form of MazF reported previously (Gogos et al., 2003), overall fold in the MazF-RNA complex is formed by three α helices (α1-α3) and seven β strands (β1–β7) aligned in a β-barrel-like arrangement. The two subunits of MazF form an extensive dimeric interface, which is predominantly nonpolar, thereby burying a total surface area after dimerization of 2,532 Å2 (19.3%) per subunit. A large number of hydrophobic and polar interactions, including salt bridges and hydrogen bonds, stabilize the dimeric interface. The dimer interface has a concave surface, a portion of which is covered by the loop (highlighted in red in Figure 1E) present between strands β1 and β2 from both subunits.

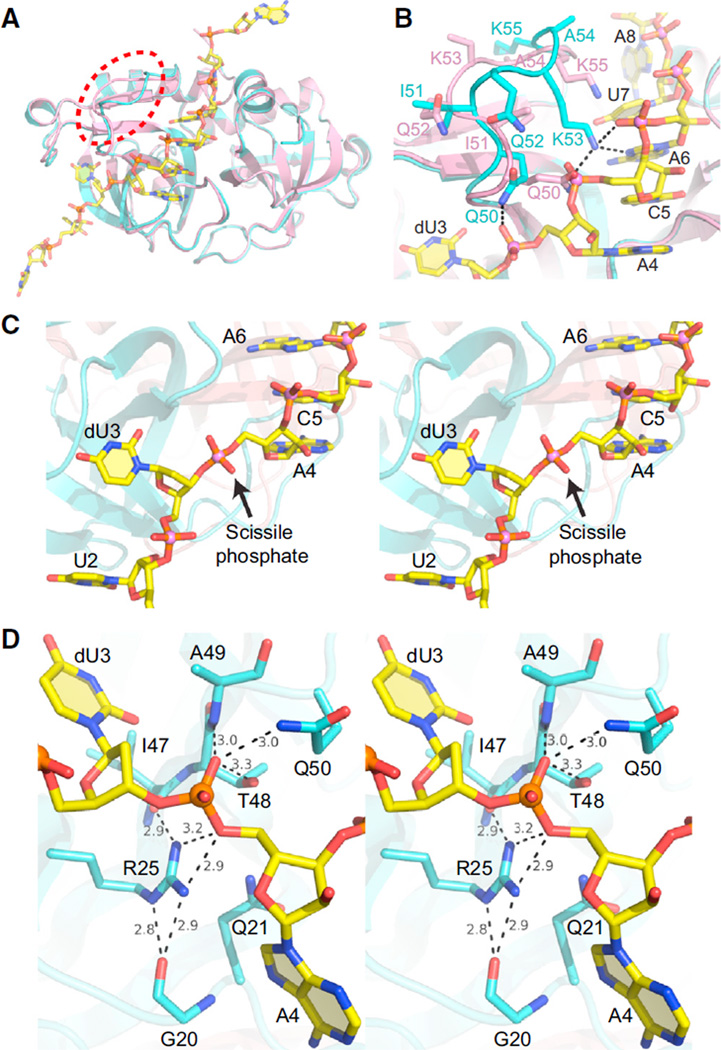

Overall, the structure of MazF dimer resembles the apo structure of MazF (root-mean-square deviation [rmsd] of 0.48 Å between corresponding Cα atoms) with the exception of a conformational change in a loop (formed by residues from Gln50 to Lys55; highlighted by a dashed red ellipsoid in Figure 2A) upon RNA binding. In the MazF-RNA complex, this conformational change results in Gln50 and Lys55 moving outward away from the RNA, whereas Gln52 and Lys53 move inward toward the bound RNA, where Lys53 interacts with it (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Structural Comparison of B. subtilis MazF in Apo Form and in Complex with Bound RNA, Trajectory of the RNA in Bound Form, and the Active Site for Bound RNA Cleavage in B. subtilis MazF-RNA Complex.

(A) Structural superposition of the apo form of MazF (pink) and MazF-RNA complex (cyan and yellow) showing conformational changes in the loop region between Gln50 and Lys55. The loop region is highlighted with the red ellipsoid.

(B) Conformational changes in the loop formed by residues from Gln50 to Lys55 in the apo form of MazF (pink) and MazF-RNA complex (cyan and yellow). Side chain atoms are shown in stick representation.

(C) Stereo view highlighting the changes in trajectory at the dU3-A4 step within the dUACAU segment of the bound RNA in the MazF-RNA complex.

(D) Stereo view of the active site in the B. subtilis MazF-RNA complex showing that the residues present around the scissile phosphate present between dU3 and A4. The numbers list hydrogen bond distances between the bridging and nonbridging oxygens of the scissible phosphate and side chain and backbone atoms of amino acids of MazF lining the active site pocket.

Sequence-Specific Recognition of mRNA Substrate by B. subtilis MazF

The RNA in an extended alignment is bound along the RNA binding interface between subunits of the MazF dimer, covering part of this dimeric interface (Figures 1D and 1E). U1 and A9 present at either end of RNA molecule are involved in crystal packing interactions and bind to symmetry-related MazF molecules in the crystal. U2 to U6 of bound RNA bind to only one of the subunits of MazF near the dimeric interface, whereas U7 and A8 bind within the dimeric interface and interact with both subunits of MazF (Figure 1E). We observe a change in the trajectory of RNA at the dU3-A4 step (stereo view in Figure 2C) in the process exposing the scissile intervening phosphate to the residues of MazF involved in cleavage process (stereo view in Figure 2D).

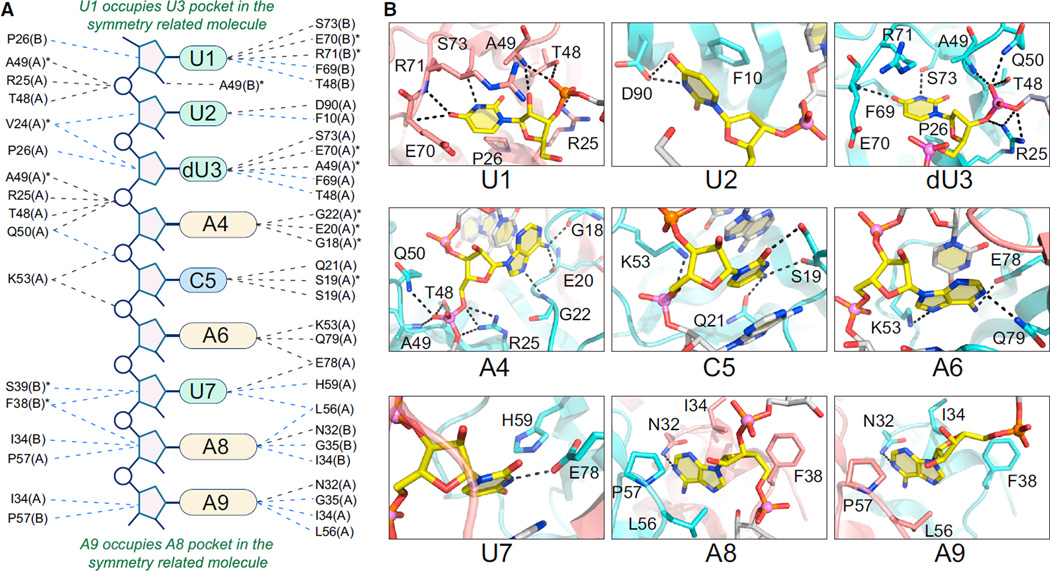

A schematic representation of interactions between protein and RNA molecules is shown in Figure 3A, establishing that MazF interacts extensively with the pentad target sequence present in the RNA chain. MazF recognizes residues from dU3 to U7, thereby encompassing the dU^ACAU segment spanning the cleavage site. We observe specific protein-RNA recognition of the bases of dU3, A4, C5, A6, and U7 (Figure 3B), supplemented by the stacking of adjacent bases A4, C5, A6, and U7 of the bound RNA in the complex (Figures 1E and 3B). The uracil base of dU3 binds in a cavity formed by Pro26, Ala49, Glu70, Arg71, and Ser73. This uracil forms two intermolecular hydrogen bonds through its Watson-Crick edge with the Ser73 and backbone amide nitrogen atom of Glu70 (Figure 3B). The adenine base of A4 forms three hydrogen bonds through its Hoogsteen edge with backbone carbonyl and amide atoms of Gly18, Glu20, and Gly22. The cytosine base of C5 is stacked between adenine bases from both sides and forms hydrogen bonds with Gln21 and main chain and side chain atoms of Ser19. The adenine base of A6 is stacked between cytosine (C5) and uracil (U7) bases and forms three hydrogen bonds through both Watson-Crick and Hoogsteen edges with Glu78, Gln79, and Lys53. The uracil base of U7 forms a hydrogen bond with Glu78 and a weak polar interaction with His59. It also forms stacking interaction on one side of the base with an adenine (A6). Surprisingly, the adenine base of A8 also binds tightly in a pocket formed by Leu56 and Pro57 of subunit A and Asn32, Ile34, and Phe38 of subunit B of MazF and forms a hydrogen bond with Asn32 from the subunit B (Figure 3B), although A8 is not an essential base for cleavage by B. subtilis MazF.

Figure 3. Sequence-Specific Recognition of RNA Containing UACAU RNA Recognition Element by B. subtilis MazF.

(A) Schematic representation of base-specific recognition of RNA substrate site by MazF. Dashed lines in black indicate hydrogen bonds, whereas dashed lines in blue show hydrophobic and van der Waal interactions between proteins and RNA. Asterisks designate interactions with main-chain atoms of the given amino acids, whereas A and B shown in parenthesis indicate two subunits of MazF.

(B) Panels showing the recognition of individual nucleotides in RNA by MazF. Intermolecular hydrogen bonds are indicated by dashed black lines. For clarity, only one nucleotide is shown in yellow in each panel.

See also Figures S2 and S3.

The first nucleotide U1 binds in the same pocket as dU3 in B subunit of the symmetry-related molecule (Figure 3B). Similarly, the adenine base of A9 binds in the A8 pocket of the B subunit of another symmetry-related molecule inside the crystal (Figure 3B). The uracil base of U2 binds on the protein surface, where it forms a hydrogen bond with Asp90 and stacking interactions with Phe10 (Figure 3B). In the structure, the oxygen atoms present at the 2′-position in the ribose sugar form water mediated hydrogen bonds with the protein atoms.

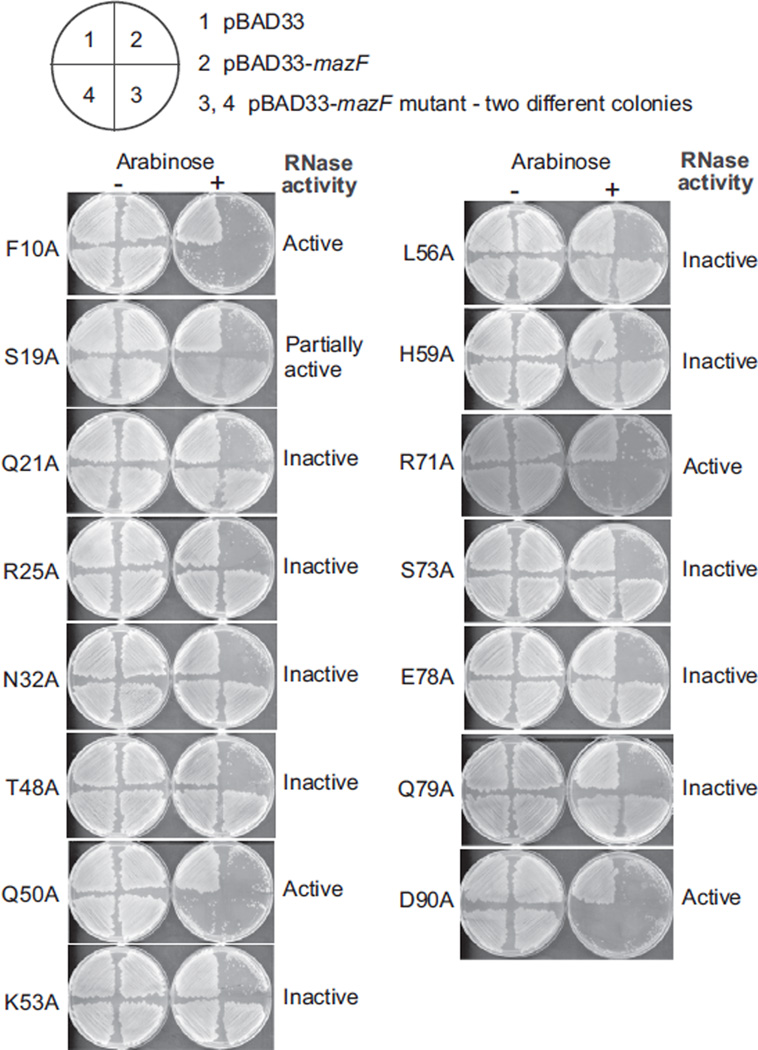

Point Mutations of MazF Residues that Interact with Bound RNA

The scissile phosphate between dU3 and A4 forms hydrogen bonds with Arg25 from one direction and with Thr48, Gln50, and main chain oxygen atom of Ala49 from the opposite direction in the structure of the B. subtilis MazF-RNA complex (Figure 2D). Therefore, we have carried out point-mutation studies on B. subtilis MazF residues, which interact with bound RNA, including those involved in recognition of the scissible phosphate, in order to investigate their role in RNA binding and cleavage (Figure 4 and Table S2).

Figure 4. Impact of MazF Point Mutations for Residues Involved in RNA Binding and Cleavage in the B. subtilis MazF-RNA Complex.

Expression of various MazF mutants under arabinose-inducible promoter (in duplicates in the bottom quadrants of the plate) was used to check the toxicity in E. coli cells. The upper left quadrant shows the expression of empty pBAD33 vector, whereas the upper right quadrant shows the expression of WT MazF as a control. Bacterial growth indicates a loss of toxicity, whereas the absence of bacterial growth shows behavior similar to WT MazF.

See also Figure S4.

For this, we expressed B. subtilis MazF mutants under arabinose-inducible promoter in pBAD33 vector in E. coli cells. The presence or absence of colonies on M9 plates in the presence of 0.1% arabinose was used as a readout to check the effect of these mutations on B. subtilis MazF activity (Figure 4). Mutation of Arg25 (R25A) and Thr48 (T48A) located near the scissile phosphate resulted in a complete loss of toxicity by MazF, suggesting their key involvement in the catalytic process. Other neighboring residues, such as Gln50 (Q50A) and Arg71 (R71A), had no effect on MazF toxicity. As expected, point mutations of residues Asp90 (D90A) and Phe10 (F10A), which interact with U2 (located outside the dU^ACAU consensus segment), had no effect on MazF toxicity. On the other hand, mutations of Ser73 (which interacts with the uracil base of dU3), Lys53 and Gln79 (which interact with the adenine base of A6), and His59 and Glu78 (which interact with the uracil base of U7) to alanine and those within the dU^ACAU consensus segment resulted in a complete loss of MazF toxicity. Mutation of Ser19 (S19A), which interacts with the cytidine base of C5, leads to only a partial loss of toxicity. Mutation of Asn32 (N32A), which forms a hydrogen bond with A8, also results in a loss of toxicity, suggesting that, even though base specificity may not be required at this position, binding in this pocket appears to be required for RNA recognition and cleavage.

Using ITC experiments, we also checked MazF mutants (R25A, K53A, S73A, and E78A) for their ability to bind to RNA substrate in vitro. In the in vivo assay described above, these four mutants resulted in a loss of toxicity of MazF. ITC binding studies on these four MazF mutants with uncleavable 9-mer RNA showed that mutations of Arg25, Lys53, and Ser73 to alanine results in 55- to 100-fold weaker RNA binding than the wild-type (WT) protein, whereas Glu78 (E78A) mutation results in close to 650-fold weaker binding with RNA than the WT protein (Figure S4A).

Crystal Packing and Stoichiometry of the B. subtilis MazF-RNA Complex

Although we used a dimeric MazF:ssRNA ratio of 1:2.2 during the cocrystallization experiments, we found only one molecule of ssRNA bound to subunit A (Figures 1E and S2A) of the B. subtilis MazF dimer in the crystal. It appears that U1 and A9 nucleotides (shown in yellow) from different RNA molecules (in the crystal lattice) that are bound to subunit B (Figure S2A) of the MazF dimer in the structure of the complex will prevent the binding of a second RNA molecule (modeled in silver) to subunit B (Figure S2B). Furthermore, the interactions formed by U1 and A9 (from different RNA molecules in the crystal lattice) with the B subunit (shown in salmon) of the MazF dimer (Figure S2A) mimics the interactions formed by dU3 and A8 with the A subunit (shown in cyan) of MazF dimer (Figure 3B).

Indeed, the molar ratio of 1:1 (one ssRNA molecule bound per MazF dimer) obtained from ITC and filter-binding experiments with a 9-mer RNA (Figures 1C and S1A) is consistent with the MazF dimer binding to RNA at only one of the two potential sites without exhibiting any preference. Our efforts to obtain crystals of the MazF-RNA complex where RNA was bound to both sites on MazF were unsuccessful despite the use of shorter 5- and 7-mer RNAs containing the 5 nt dU^ACAU consensus binding and cleavage sequence. Crystals obtained with shorter (5- and 7-mer) RNAs showed no RNA bound to it, suggesting that MazF is likely to bind to shorter RNAs with lower affinity.

Coexpression and Structure Determination of the B. subtilis MazE-MazF Complex

To understand the molecular basis by which the formation of the TA complex formed by MazF and MazE from B. subtilis prevents RNA binding and cleavage, we solved the structure of the B. subtilis MazE-MazF complex. Though B. subtilis MazE could not be expressed by itself, coexpression of MazE and MazF resulted in a soluble and stable complex in solution. We successfully obtained diffraction quality crystals of the complex and collected a data set to 2.9 Å resolution with selenomethioninelabeled proteins. The structure of the MazE-MazF complex was solved with Se phasing by single-wavelength anomalous dispersion method. The final model of the MazE-MazF complex has been refined to an R factor = 25.3% and free R factor = 29.9%, with X-ray statistics listed in Table S1. The initial five residues at the N terminus, the final ten residues at the C terminus of MazE, and 6–11 residues present in the loop between strands b1 and b2 in MazF were not included in the structure of the complex because of the absence of well-defined electron density (presumed to be disordered).

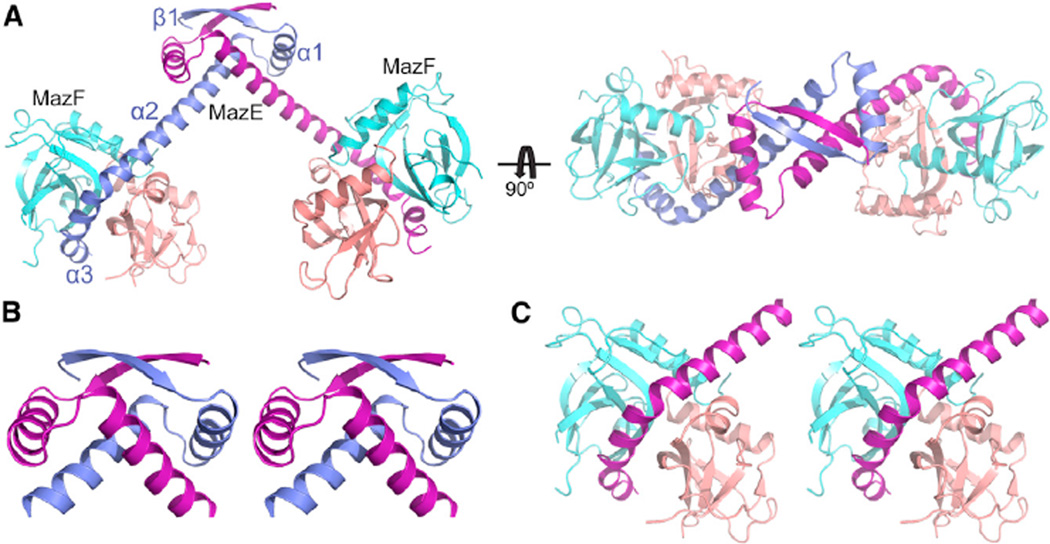

Structure of B. subtilis MazE-MazF Complex and Overall Fold of B. subtilis MazE

The asymmetric unit contains a hexameric complex formed by two copies of MazF dimer bound to one copy of MazE dimer arranged in a MazF2-MazE2-MazF2 alignment in the complex (Figure 5A). The quaternary structure predicted by the program PISA (proteins, interfaces, structures, and assemblies) using the coordinates of the MazE-MazF complex corresponds to the hexameric composition present in the asymmetric unit (Krissinel and Henrick, 2007). The apparent molecular weight obtained from the gel filtration experiments matches the theoretically calculated molecular weight (73 kDa) of heterohexameric complex structure having one copy of the MazE dimer and two copies of the MazF dimer (Figure S5A). The MazE fold contains a β strand (β1) at the N terminus followed by three α helices (α1– α3), and the α1 helix and N-terminal region of α2 helix along with β1 strand forming the N-terminal domain of MazE. This fold (stereo pair in Figure 5B) resembles the ribbon-helix-helix (RHH) motif seen in transcription factors capable of binding to DNA. The β strand present at the N terminus of MazE forms an antiparallel β sheet upon dimerization. In the dimeric MazE, RHH motifs from each subunit are intertwined in order to form a stable domain with 2-fold symmetry. The dimer interface of MazE is predominantly hydrophobic in nature. The total surface area buried on dimerization is 1,854 Å2 (23.8%) per subunit. By contrast, the α2 and α3 helices extend away from the N-terminal domain of MazE and bind tightly to the dimeric interface of MazF (stereo view in Figure 5C). In the MazE-MazF complex, there is no interaction between the two MazF dimers or between the dimeric RHH domain of MazE and the dimer of MazF (Figure 5A). The overall structure of MazF dimers present in the MazE-MazF complex resembles the MazF dimer present in MazF-RNA complex (rmsd of 0.9 Å) except that residues present in the loop between Gln50 to Lys55 do not undergo any conformational change, as seen in MazF-RNA complex. Binding of MazE also displaces the loop present between strands β1 and β2 in MazF dimers in MazE-MazF complex.

Figure 5. Structure of Heterohexameric B. subtilis MazE-MazF Complex and Overall Fold of B. subtilis MazE.

(A) Ribbon representation of two views of the B. subtilis MazE-MazF complex. The two chains of MazF dimer are colored cyan and salmon, whereas the two chains of dimeric MazE are colored blue and purple. The hexameric complex is formed by two dimers of MazF bound to one dimer of MazE in the form of MazF2-MazE2-MazF2.

(B) Stereo view of RHH motif present at the N-terminal end of MazE.

(C) Stereo view of the region in MazE-MazF complex where C-terminal helices of MazE (purple) interact with MazF dimer.

See also Figures S5 and S6 and Table S1.

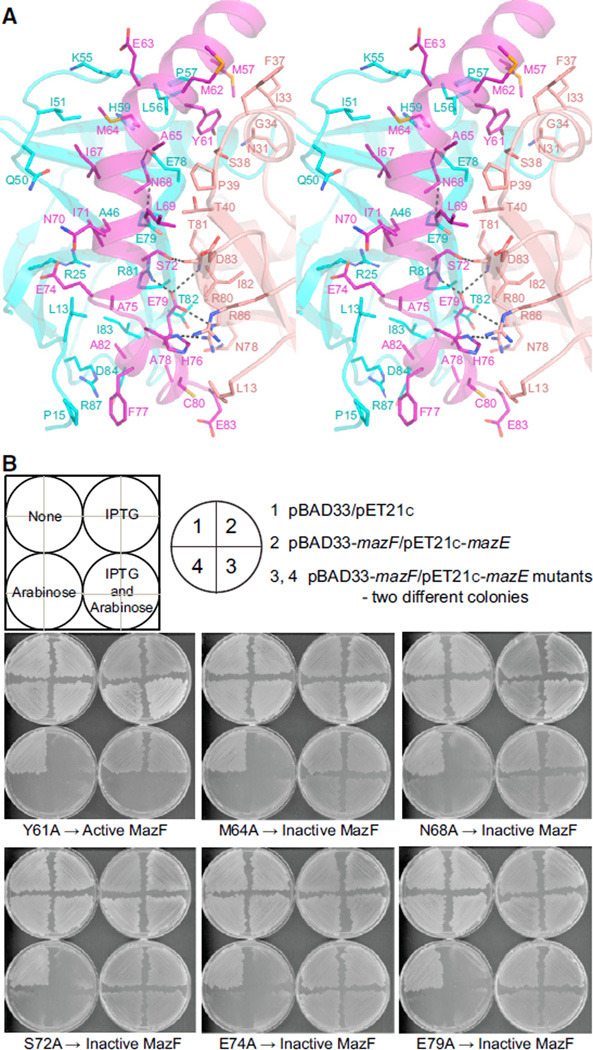

Intermolecular Interactions and Impact of MazE Mutations on MazE-MazF Complex Formation in B. subtilis

Antitoxin MazE binds to the dimer interface of MazF through its C-terminal α2 and α3 helices (Figures 5A and 5C). In MazE, helix α2 (Arg33 to Glu74) is followed by short helix α3 (His76 to Glu81), and Ala75 connects these two helices. Indeed, MazE residues from Met57 to Glu83 are tightly packed within the concave surface associated with the dimeric interface of MazF and interact extensively with residues from both subunits of MazF (Figures 6A and S7A).

Figure 6. Details of Intermolecular Protein-Protein Interaction Interface in B. subtilis MazE-MazF Complex and Impact of B. subtilis MazE Point Mutations on the Toxicity of B. subtilis MazE-MazF Complex in E. coli Cells.

(A) Stereo view of the interface formed by residues from MazE and MazF in the B. subtilis complex. MazE is colored purple, whereas two chains in MazF dimer are colored cyan and salmon. Intermolecular hydrogen bonds are indicated by dashed black lines.

(B) Effect of single amino acid mutations in B. subtilis MazE on the toxicity of B. subtilis MazE-MazF complex in E. coli cells. The expression of various MazE mutants (in duplicates in the bottom quadrants of the plate) under IPTG-inducible promoter along with WT MazF under arabinose-inducible promoter was used to check the toxicity in the E. coli cells. The upper left quadrants show the expression of empty pBAD33 and pET21c vector,whereas the upper right quadrants show the coexpression of WT MazF and MazE as a control. Bacterial growth indicates a loss of binding of MazE with MazF due to mutation in MazE, whereas the absence of bacterial growth shows behavior similar to WT MazF.

See also Figure S7.

The side chain atoms of residues Met57, Tyr61, Met64, Ile67, and Ile71 present at the C-terminal end of the α2 helix of MazE interact with a hydrophobic region present within the dimeric interface of MazF (Figure 6A). Recognition involves a polar region on the dimer interface of MazF, where Asn68 of MazE forms hydrogen bonds with Glu78 and Glu79 of one subunit of MazF, whereas Ser73 of MazE forms hydrogen bonds with Thr81 present in the second subunit of MazF. The interaction of MazE helix α3 (via Ala78 and Ala82) with MazF on the dimer interface is also predominantly hydrophobic in nature (Figure 6A). Glu79 located on helix α3 of MazE forms a salt bridge interaction, and Arg80 and Arg81 come from subunit A and B of MazF, respectively. His76 present in MazE interacts with Arg86 residue located in the B subunit of MazF. Eight residues located at the C-terminal end of MazE were not seen in the electron density maps and, thus, are not likely to be involved in the protein-protein interaction.

Five key residues (Tyr61, Met64, Asn68, Ser72, Glu74, and Glu79) present in the C-terminal region of MazE were mutated to Ala in order to elucidate their role in the formation of MazE-MazF complex (Figure 6B). The Tyr61Ala mutation in MazE resulted in a loss of growth of E. coli cells following the coexpression of MazE-Y61A and MazF, suggesting that this mutation resulted in a loss of interaction between MazE and MazF, and no colonies could form because of the presence of active MazF. Other point mutations resulted in normal to slightly reduced growth, suggesting that single mutations of these residues alone were not sufficient to abolish the interaction between toxin and antitoxin (Figure 6B).

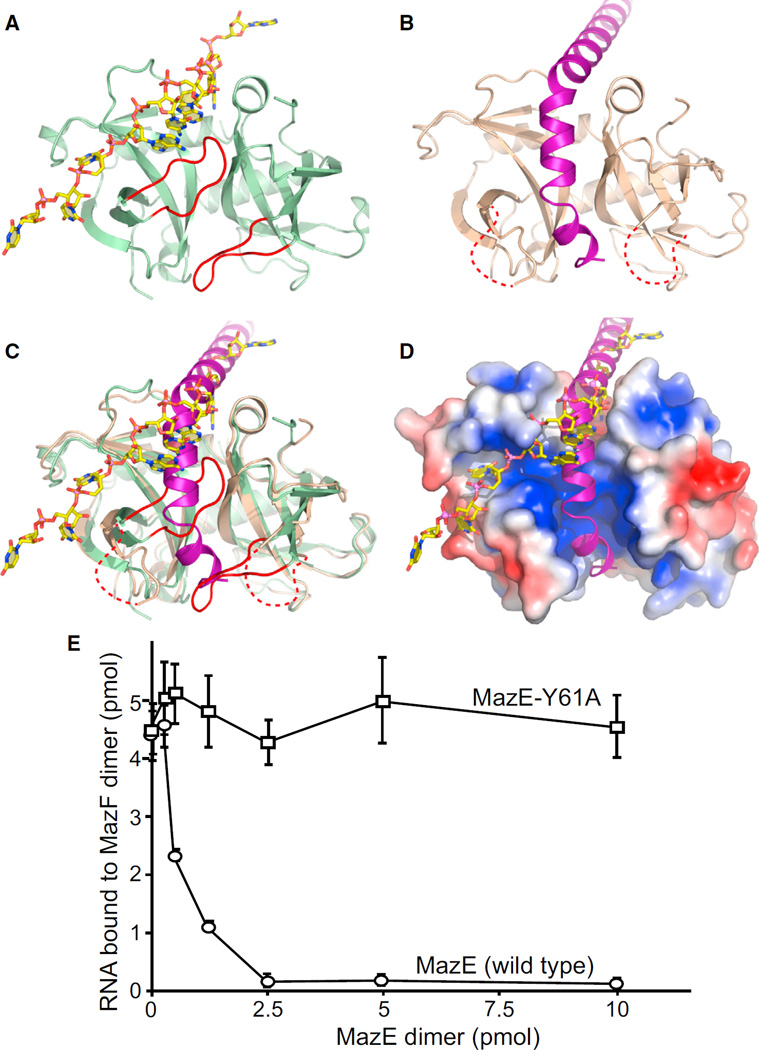

Competition Assay between MazE and RNA with MazF

Competition filter-binding assays were performed in order to analyze whether MazE and MazE-Y61A could effectively inhibit the binding of RNA to MazF. A constant amount of MazF dimer (5 pmol) was incubated with variable amounts of MazE and MazE-Y61A dimer (0.25–10 pmol) on ice for 15 min. This was followed by the addition of 5 pmol of radiolabeled RNA (9-mer, UUdUACAUAA) to the reaction mixture, which was then incubated for 1 hr at 4°C. The amount of RNA bound to MazF was quantified with filter-binding assay. As shown in Figure 7E, RNA binding to MazF is completely blocked when MazE dimer (2.5 pmol) is present at half the concentration of MazF dimer (5 pmol). On the other hand, MazE-Y61A has no effect on the binding between MazF and RNA, indicating that this mutation (Y61A) results in a loss of interaction between MazE and MazF. Results obtained from the competition assays validate the concept that MazF cannot bind to and cleave target RNA in the presence of MazE.

Figure 7. Structural Comparison of B. subtilis MazF-RNA and B. subtilis MazE-MazF Complexes Highlighting Overlap of Binding Site on the Dimeric Interface of MazF for Bound RNA and MazE and Competition Assay between MazE and ssRNA for MazF.

(A) Structure of the MazF-RNA complex. A loop connecting β1 and β2 strands from each subunit and containing residues involved in RNA binding (highlighted in red) occupies part of the interface between the two subunits of MazF (light green).

(B) Structure of the MazE-MazF complex. The C-terminal helices of MazE (purple) are positioned within the interface between the two subunits of MazF (light orange), thereby displacing the loop connecting β1 and β2 strands from each subunit, and these loops are disordered in the MazE-MazF complex.

(C) Structural superposition of MazF-RNA complex and MazE-MazF complex showing overlap of binding sites for RNA and MazE on the dimeric interface of MazF. MazF is colored light green in the MazF-RNA complex, whereas it is colored light orange in the MazE-MazF complex. In the MazE-MazF complex, the C-terminal helical region of MazE (purple) displaces the loop connecting β1 and β2 strands from each subunit (highlighted in red), as seen in the MazF-RNA complex structure.

(D) Electrostatic surface representation of MazF from the MazE-MazF complex with superposed RNA in the same view as in (C).

(E) Filter-binding competition assay of MazF with ssRNA and MazE. A constant amount of MazF dimer (5 pmol) was incubated with variable amounts of WT MazE (circles) or MazE-Y61A (squares) on ice for 15 min. Then, labeled RNA (5 pmol) was added and incubated for 1 hr on ice. The amount of RNA bound to MazF was quantified with filter-binding assay. Error bars represent SEM (n = 3).

See also Figure S7.

DISCUSSION

Our study has elucidated unique insights into mRNA recognition and cleavage by toxin MazF and its regulation by antitoxin MazE through the structural and mutational analysis of toxin-mRNA substrate (MazF-RNA) and toxin-antitoxin (MazF-MazE) complexes on the same system (B. subtilis).

Sequence-Specific Recognition of RNA by B. subtilis MazF

Since the discovery of ACA-specific MazF in E. coli, a number of MazF homologs have been identified that cleave mRNA at specific sites within three-, five-, or seven-base sequences in bacteria and archaea. However, the molecular basis by which they recognize and cleave substrate mRNA sites has remained elusive. In this report, we present the crystal structure of B. subtilis MazF bound to RNA containing a U^ACAU sequence. The crystal structure of the MazF-RNA complex provides the molecular basis underlying sequence-specific RNA recognition and cleavage by endoribonuclease MazF (Figures 1D and 1E). In the MazF-RNA complex structure, the five-base target sequence is tightly bound to the protein in such a way that the bases project toward the dimer interface of the protein, whereas the backbone phosphate moieties project outward and away from the protein surface (Figure 1D). Thus, interaction between RNA and protein occurs mainly through interactions with bases, facilitating sequence-specific recognition of RNA substrates.

Sequence analysis of MS2 RNA cleavage products obtained at much lower efficiency in comparison to the five-base substrate sequence, suggesting that base substitution could be tolerated at the position of the two purine (adenine) bases but not at the position of pyrimidine bases within the UACAU recognition sequence (Park et al., 2011). It is possible that a pyrimidine base could be accommodated inside a purine binding pocket without any steric hindrance, thereby resulting in the cleavage of RNA at such locations, albeit with a lower efficiency. Recently, it has been shown that the replacement of all Arg residues with canavanine (a toxic Arg analog) in B. subtilis MazF changes its substrate specificity to a six-base target sequence U^ACAUA (Ishida et al., 2013). Examination of the location of all Arg residues present in the structure of the MazF-RNA complex suggests that the change in substrate specificity is likely due to overall conformational changes occurring within the MazF dimer, mainly due to the substitution of Arg81 and Arg87 present at the dimer interface, Arg25 at the cleavage site and Arg37 present near the RNA binding pocket involving recognition of the sixth nucleotide.

Similar to the current structure of B. subtilis MazF-RNA complex, other MazF homologs are also likely to bind their RNA substrates within the dimer interface, key residues being positioned within two loops present between β1 and β2 and β3 and β4 strands. It is conceivable that small changes in the RNA binding site due to different lengths and composition of amino acids within these two loops and/or within the dimeric interface binding channel could result in different sequence-specific RNA recognition for other bacterial MazF homologs (Figure S4B).

Previously, a model of Kid toxin bound to U^A(A/C)-containing RNA was constructed on the basis of an analysis of NMR chemical shift perturbation and mutagenesis data (Kamphuis et al., 2006). A structural comparison of the model of Kid-RNA complex (Figure S3B) (PDB ID: 2C06) with the structure of MazF-RNA complex (Figure S3A) shows similarity in RNA binding to the toxin dimer interface but differences in the directionality of bound RNA and the location of active site and position as well as the orientation of bases and backbone phosphates on the protein surface (Figure S3C). At this time, a structure of Kid toxin in complex with its RNA substrate would be needed to comparatively evaluate the mode of recognition and cleavage of target RNAs by MazF and Kid toxins.

Active Site and Reaction Mechanism

The structure of MazF in complex with RNA has identified location of the catalytic center within the MazF toxin. The scissile phosphate positioned between dU3 and A4 of the bound RNA is surrounded by the side chains of Arg25 from one direction, and the side chains of Thr48 and Gln50 and the main chain nitrogen atom of Ala49 from the opposing direction in the structure of the B. subtilis MazF-RNA complex (Figure 2D), all of which form hydrogen bonds with the oxygen atoms of the scissile phosphate group. Unlike that of Gln50, mutation of Arg25 and Thr48 to Ala results in a loss of toxicity (Figure 4), thus supporting their role in the catalytic process. These two residues are highly conserved among various bacterial MazF homologs (Figure S4B). The main chain oxygen atoms of Gly22 and Ile47 form hydrogen bonds with the guanidinium group of Arg25 and, thus, orient it properly for interaction with the scissile phosphate (Figure 2D).

Previous studies on E. coli MazF have shown that the RNA product obtained after MazF-mediated cleavage possesses a 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate at the 3′ end and a free 5′-OH group at the 5′ end. On the basis of the cleavage product, it has been suggested that MazF cleaves mRNA in a manner similar to RNase A and T1, and the cleavage is mediated by acid-base catalysis (Zhang et al., 2005). However, unlike RNase A, B. subtilis MazF does not contain a pair of histidine residues in the active site region. It is not clear at this time what residue or combination of residues act as the general base to activate the 2′-OH for attack of the phosphate in order to generate the 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate. It is likely that the side chain of Arg25 serves to stabilize the transition state and/or product after the cleavage of the P-O bond.

Comparison between Toxin-Antitoxin Complexes from E. coli and B. subtilis

Although stoichiometry and overall arrangement of MazE and MazF dimers are similar in the MazE-MazF complexes of B. subtilis (Figure 5A) (this study) and E. coli (Figure S5B) (Kamada et al., 2003), the quaternary structure and the fold of antitoxin MazE are different for these two species. B. subtilis MazE possess an RHH motif at the N-terminal end and binds to B. subtilis MazF via a helical structure (Figures 5A and 5C), whereas E. coli MazE contains a β barrel core at the N-terminal end and interacts with E. coli MazF mainly by a long loop located at the C-terminal end (Figure S5B). Unlike MazE from E. coli and B. subtilis, there is significant sequence and structural similarity between MazF from E. coli and B. subtilis (sequence homology of ~40%). However, due to different sequence composition and structural features of MazEs in the two species, it is likely that these antitoxins have evolved independently for binding to their specific cognate toxin. Consistent with this proposal, previous studies have shown that E. coli MazE cannot neutralize B. subtilis MazF (Park et al., 2011).

Structure of B. subtilis MazE Antitoxin and Comparison with Other Antitoxins

The N-terminal domain of B. subtilis MazE shows structural similarity to RHH family of transcription factors. The RHH motif has been shown to bind DNA in a sequence-specific manner and to regulate various cellular processes (Schreiter and Drennan, 2007). A Dali search for a structural homolog for B. subtilis MazE suggests correspondence with ParD of the ParE-ParD complex, FitA of the FitA-FitB complex, and RHH-motif-containing transcription factors (Holm and Rosenström, 2010). The RHH motif has also been shown to be present in CcdA (CcdA-CcdB) and RelB (RelB-RelE) antitoxins. Although ParD, RelB, CcdA, FitA, and B. subtilis MazE antitoxins have similar RHH motifs, the structure and mode of action of their toxin counterparts are very different. Unlike the B. subtilis MazE-MazF complex (Figure 5A), the ParD-ParE complex forms heterotetrameric complex (ParD2-ParE2) where the two helices at the C-terminal ends of the antitoxin dimer bind to one dimer of toxin and are placed relatively close to each other (Dalton and Crosson, 2010) (Figure S5C). Results obtained from DNA binding assays suggest that B. subtilis MazE in context of the MazE-MazF complex does not bind to its own promoter region (Figure S6) and, thus, doesn’t appear to regulate the transcription of the mazEF operon.

An Explanation as to Why MazF Bound to MazE in B. subtilis Cannot Cleave mRNA

The structural superposition of B. subtilis MazF structure in complex with RNA (Figure 7A) and in complex with B. subtilis MazE (Figure 7B) as shown in Figures 7C and 7D provides an explanation as to why MazF does not cleave mRNA during normal growth conditions. The structural superposition shows that RNA nucleotide bases from A4–A9 share the binding site on MazF with the helical region of MazE (Figures 7C and 7D). The protein-protein interaction interface between MazE and MazF (2,843 Å2) is larger than the MazF-RNA interaction interface (2,153 Å2), suggesting that MazF is likely to have a higher affinity for MazE over its RNA substrate. In the B. subtilis MazE-MazF complex structure, MazE binds to MazF along the dimer interface (Figure 7B), and it even occupies part of the putative modeled RNA binding site on the second subunit of MazF (Figure S7B). In addition, the helical regions of MazE displace the MazF loop present between strands β1 and β2, which contain residues involved in RNA binding in both subunits of MazF (red loops in Figures 7A and 7C). No electron density was observed for this loop, and it is likely to be disordered in the structure of the MazE-MazF complex (Figure 7B). Thus, binding of one subunit of the MazE dimer to the MazF dimer can prevent RNA binding and cleavage within both subunits of MazF dimer. Results obtained from the competition assay show that MazF binds to MazE with higher affinity than the substrate RNA and, thus, in the presence of MazE, MazF cannot bind to or cleave substrate RNA (Figure 7E).

Biological Implications

During heterologous expression in E. coli cells, B. subtilis MazF was seen to be less toxic than E. coli MazF, likely due to the five-base UACAU RNA substrate sequence for B. subtilis MazF over the three-base ACA RNA substrate for the E. coli MazF. Assuming that RNA sequences contain an equal number of bases and have random sequence composition, the five-base B. subtilis MazF substrate sequence is likely to be found once every 1,024 base sequences. Previously, analysis of the presence of MazF target sequences in every open reading frame present in B. subtilis genome resulted in the identification of proteins mostly involved in secondary metabolite biosynthesis, transport, and catabolism (Park et al., 2011). B. subtilis proteins containing a large number of substrate sequences in their mRNA include polyketide synthase, surfactin synthetase, and plipastatin synthetase. Microbial polyketides have been shown to play a role in self-defense and aggression (Hutchinson, 1999). Surfactin, one of the antibiotics produced by B. subtilis and surfactin synthetases, is also essential for biofilm formation (Stein, 2005). Plipastatin is a lipopeptide antifungal antibiotic produced by B. subtilis (Tsuge et al., 2007).

B. subtilis MazF shares high sequence similarity with Grampositive bacteria, including pathogenic Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus, Clostridium difficile, and Staphylococcus aureus (Park et al., 2011). The B. subtilis MazF shares 65% and 71% amino acid sequence identity with MazF from S. aureus and C. difficile, respectively, and MazFs from these three organisms share the same five-base U^ACAU RNA substrate sequence (Rothenbacher et al., 2012; Zhu et al., 2009). In S. aureus, the target sequence is common in several genes important for pathogenesis, including the sraP gene, which is known to play an important role in cell communication between the pathogen and human platelets (Siboo et al., 2005; Zhu et al., 2009).

In this study, we elucidated the structures of MazF-RNA and MazE-MazF complexes that provided the molecular basis of recognition of sequence-specific mRNA targets by MazF and the structural basis by which binding of antitoxin prevents the toxin from exerting its endoribonuclease activity. These results have significant implications for our understanding of the mode of action of TA complexes during normal and stress conditions.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Please refer to the Supplemental Experimental Procedures for detailed methodology on protein expression and purification, data collection and structure determination, nitrocellulose filter-binding assays, plasmids, site-directed mutagenesis for in vivo assays, gel filtration chromatography, and electrophoretic mobility shift assays.

Protein Expression and Purification

The B. subtilis mazF gene was cloned in pET-SUMO vector (Invitrogen) with a His6-SUMO tag at the N terminus. Proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells in lysogeny broth. Unlike E. coli MazF, which inhibits cell growth within 30 min after isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) induction, B. subtilis MazF exhibits less toxicity, and growth inhibition starts 2 hr after IPTG induction. Thus, E. coli cells expressing B. subtilis MazF were harvested 2 hr after induction and used for protein purification. For coexpression of TA complex, B. subtilis mazE along with mazF were cloned at two different multiple cloning sites in the modified pRSFDuet-1 vector (modified pRSFDuet-1 vector with His6-SUMO tag at the N terminus attached only to mazE). Our efforts to obtain soluble recombinant MazE protein for competition assay without any affinity tag or with His6-SUMO tag were unsuccessful. We were successful in obtaining soluble MazE protein when the mazE gene was cloned in the pCold-PST vector having His6-Protein S2 (PrS)2 tag at the N terminus.

ITC Measurements

ITC experiments were performed with a VP-ITC calorimeter (MicroCal) at 25°C, and MicroCal Origin software was used for curve fitting, equilibrium dissociation constant, and molar ratio calculations. The WT and mutant protein samples were dialyzed overnight against a buffer containing 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, and 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol at 4°C. Purified and desalted RNA (UUdUACAUAA) was purchased from Dharmacon and dissolved in dialysis buffer. Calorimetric titration was performed by injection of RNA into a cell containing MazF.

Crystallization and Structure Determination

The purified B. subtilis MazF dimer was mixed with 9-mer ssRNA (UUdUA CAUAA) in a molar ratio of 1:2.2 and incubated on ice for 1 hr. The complex crystals were grown with the hanging drop vapor diffusion method by mixing the protein-RNA complex with an equal volume of reservoir solution containing 0.2 M sodium iodide and 20% w/v PEG 3350. Crystals of SeMet-labeled MazE-MazF complex were grown with the hanging drop vapor diffusion method by mixing the protein-protein complex with an equal volume of reservoir solution containing 0.2 M calcium chloride, 0.1 M Bis-Tris (pH 6.5), and 3% v/v isopropanol.

The structure of B. subtilis MazF in complex with RNA was solved by molecular replacement using the program PHASER on the basis of the apo structure of MazF (PDB ID: 1NE8) (Gogos et al., 2003; McCoy et al., 2007). We solved the crystal structure of B. subtilis MazE-MazF complex by using the MR-SAD method with B. subtilis MazF as a search model and data collected at Se-peak wavelength by the program PHENIX.AutoSol (Zwart et al., 2008).

Assay of MazF Toxicity In Vivo

E. coli BL21(DE3) was transformed with pBAD33-mazF or pBAD33-mazF mutant. Transformed cells were then grown on M9 plates containing 0.2% glycerol and casamino acids in the presence or absence of 0.1% arabinose. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 18 hr.

Assay of MazE Neutralization Activity In Vivo

E. coli BL21(DE3) was transformed with pBAD33-mazF along with pET21c-mazE or pET21c-mazE mutant. Transformed cells were then grown on M9 plates containing 0.2% glycerol and casamino acids with 0.05 mM IPTG, 0.1% arabinose, and 0.05 mM IPTG plus 0.1% arabinose as well as without both inducers. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 18 hr.

Filter-Binding Competition Assay of MazE and ssRNA for MazF

For filter-binding competition assay, a constant amount of MazF dimer (5 pmol) was incubated with variable amounts of His6-PrS2-tagged MazE or MazE-Y61A (0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, 10, and 20 pmol) on ice for 15 min in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) containing 75 mM NaCl and 1 mM dithiothreitol. This was followed by the addition of radiolabeled RNA (5 pmol), and the mixture was incubated for another 1 hr on ice. The amount of RNA bound to MazF was quantified with filter-binding assay.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the staff of X-29 beamline at the National Synchrotron Light Source, Brookhaven National Laboratory, and the ID-24-C and ID-24-E beam-lines at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory, for their help with data collection. This research was supported by funds from the Abby Rockefeller Trust and the Maloris Foundation to D.J.P.

Footnotes

ACCESSION NUMBERS

The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank and are available under accession numbers 4MDX (B. subtilis MazF-RNA complex) and 4ME7 (B. subtilis MazE-MazF complex).

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information contains Supplemental Experimental Procedures, seven figures, and two tables and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2013.09.006.

REFERENCES

- Brown BL, Wood TK, Peti W, Page R. Structure of the Escherichia coli antitoxin MqsA (YgiT/b3021) bound to its gene promoter reveals extensive domain rearrangements and the specificity of transcriptional regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:2285–2296. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.172643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buts L, Lah J, Dao-Thi MH, Wyns L, Loris R. Toxin-antitoxin modules as bacterial metabolic stress managers. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005;30:672–679. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton KM, Crosson S. A conserved mode of protein recognition and binding in a ParD-ParE toxin-antitoxin complex. Biochemistry. 2010;49:2205–2215. doi: 10.1021/bi902133s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jonge N, Garcia-Pino A, Buts L, Haesaerts S, Charlier D, Zangger K, Wyns L, De Greve H, Loris R. Rejuvenation of CcdB-poisoned gyrase by an intrinsically disordered protein domain. Mol. Cell. 2009;35:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes K, Christensen SK, Løbner-Olesen A. Prokaryotic toxin-antitoxin stress response loci. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005;3:371–382. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogos A, Mu H, Bahna F, Gomez CA, Shapiro L. Crystal structure of YdcE protein from Bacillus subtilis. Proteins. 2003;53:320–322. doi: 10.1002/prot.10457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves D, Santos-Sierra S, Giraldo R, Sabariegos-Jareño R, de la Cueva-Méndez G, Boelens R, Díaz-Orejas R, Rafferty JB. Structural and functional analysis of the kid toxin protein from E. coli plasmid R1. Structure. 2002;10:1425–1433. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00856-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L, Rosenström P. Dali server: conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(Web Server issue):W545–W549. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson CR. Microbial polyketide synthases: more and more prolific. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:3336–3338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida Y, Park JH, Mao L, Yamaguchi Y, Inouye M. Replacement of all arginine residues with canavanine in MazF-bs mRNA interferase changes its specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:7564–7571. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.434969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamada K, Hanaoka F, Burley SK. Crystal structure of the MazE/MazF complex: molecular bases of antidote-toxin recognition. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:875–884. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00097-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamphuis MB, Bonvin AM, Monti MC, Lemonnier M, Muñoz-Gómez A, van den Heuvel RH, Díaz-Orejas R, Boelens R. Model for RNA binding and the catalytic site of the RNase Kid of the bacterial parD toxin-antitoxin system. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;357:115–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamphuis MB, Monti MC, van den Heuvel RH, López-Villarejo J, Díaz-Orejas R, Boelens R. Structure and function of bacterial kid-kis and related toxin-antitoxin systems. Protein Pept. Lett. 2007;14:113–124. doi: 10.2174/092986607779816096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;372:774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li GY, Zhang Y, Chan MC, Mal TK, Hoeflich KP, Inouye M, Ikura M. Characterization of dual substrate binding sites in the homodimeric structure of Escherichia coli mRNA interferase MazF. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;357:139–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loris R, Dao-Thi MH, Bahassi EM, Van Melderen L, Poortmans F, Liddington R, Couturier M, Wyns L. Crystal structure of CcdB, a topoisomerase poison from E. coli. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;285:1667–1677. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madl T, Van Melderen L, Mine N, Respondek M, Oberer M, Keller W, Khatai L, Zangger K. Structural basis for nucleic acid and toxin recognition of the bacterial antitoxin CcdA. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;364:170–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki S, Takiguchi S, Miki T, Horiuchi T. Modulation of DNA supercoiling activity of Escherichia coli DNA gyrase by F plasmid proteins. Antagonistic actions of LetA (CcdA) and LetD (CcdB) proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:12244–12251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maté MJ, Vincentelli R, Foos N, Raoult D, Cambillau C, Ortiz-Lombardía M. Crystal structure of the DNA-bound VapBC2 antitoxin/toxin pair from Rickettsia felis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:3245–3258. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattison K, Wilbur JS, So M, Brennan RG. Structure of FitAB from Neisseria gonorrhoeae bound to DNA reveals a tetramer of toxin-antitoxin heterodimers containing pin domains and ribbon-helix-helix motifs. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:37942–37951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605198200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Cryst. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KJ, Jenkins JL, Kielkopf CL. Large favorable enthalpy changes drive specific RNA recognition by RNA recognition motif proteins. Biochemistry. 2011;50:1429–1431. doi: 10.1021/bi102057m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura T, Hiraga S. Mini-F plasmid genes that couple host cell division to plasmid proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1983;80:4784–4788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.15.4784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Yamaguchi Y, Inouye M. Bacillus subtilis MazF-bs (EndoA) is a UACAU-specific mRNA interferase. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:2526–2532. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini O, Mathy N, Gogos A, Shapiro L, Condon C. The Bacillus subtilis ydcDE operon encodes an endoribonuclease of the MazF/ PemK family and its inhibitor. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;56:1139–1148. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothenbacher FP, Suzuki M, Hurley JM, Montville TJ, Kirn TJ, Ouyang M, Woychik NA. Clostridium difficile MazF toxin exhibits selective, not global, mRNA cleavage. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:3464–3474. doi: 10.1128/JB.00217-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiter ER, Drennan CL. Ribbon-helix-helix transcription factors: variations on a theme. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007;5:710–720. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher MA, Piro KM, Xu W, Hansen S, Lewis K, Brennan RG. Molecular mechanisms of HipA-mediated multidrug tolerance and its neutralization by HipB. Science. 2009;323:396–401. doi: 10.1126/science.1163806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster CF, Bertram R. Toxin-antitoxin systems are ubiquitous and versatile modulators of prokaryotic cell fate. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2013;340:73–85. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimazu T, Degenhardt K, Nur-E-Kamal A, Zhang J, Yoshida T, Zhang Y, Mathew R, White E, Inouye M. NBK/BIK antagonizes MCL-1 and BCL-XL and activates BAK-mediated apoptosis in response to protein synthesis inhibition. Genes Dev. 2007;21:929–941. doi: 10.1101/gad.1522007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siboo IR, Chambers HF, Sullam PM. Role of SraP, a Serine-Rich Surface Protein of Staphylococcus aureus, in binding to human platelets. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:2273–2280. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.4.2273-2280.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein T. Bacillus subtilis antibiotics: structures, syntheses and specific functions. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;56:845–857. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuge K, Matsui K, Itaya M. Production of the non-ribosomal peptide plipastatin in Bacillus subtilis regulated by three relevant gene blocks assembled in a single movable DNA segment. J. Biotechnol. 2007;129:592–603. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Y, Inouye M. mRNA interferases, sequence-specific endoribonucleases from the toxin-antitoxin systems. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2009;85:467–500. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(08)00812-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Y, Inouye M. Regulation of growth and death in Escherichia coli by toxin-antitoxin systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011;9:779–790. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Y, Park JH, Inouye M. Toxin-antitoxin systems in bacteria and archaea. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2011;45:61–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Zhang J, Hoeflich KP, Ikura M, Qing G, Inouye M. MazF cleaves cellular mRNAs specifically at ACA to block protein synthesis in Escherichia coli. Mol. Cell. 2003;12:913–923. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00402-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Zhang J, Hara H, Kato I, Inouye M. Insights into the mRNA cleavage mechanism by MazF, an mRNA interferase. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:3143–3150. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411811200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Zhang Y, Teh JS, Zhang J, Connell N, Rubin H, Inouye M. Characterization of mRNA interferases from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:18638–18643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512693200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Phadtare S, Nariya H, Ouyang M, Husson RN, Inouye M. The mRNA interferases, MazF-mt3 and MazF-mt7 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis target unique pentad sequences in single-stranded RNA. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;69:559–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06284.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Inoue K, Yoshizumi S, Kobayashi H, Zhang Y, Ouyang M, Kato F, Sugai M, Inouye M. Staphylococcus aureus MazF specifically cleaves a pentad sequence, UACAU, which is unusually abundant in the mRNA for pathogenic adhesive factor SraP. J. Bacteriol. 2009;191:3248–3255. doi: 10.1128/JB.01815-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwart PH, Afonine PV, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Hung LW, Ioerger TR, McCoy AJ, McKee E, Moriarty NW, Read RJ, Sacchettini JC, et al. Automated structure solution with the PHENIX suite. Methods Mol. Biol. 2008;426:419–435. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-058-8_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.