Abstract

A young mother presented to a major trauma centre following a road traffic collision. Her admission CT traumagram demonstrated liver and renal lacerations, spinal and pelvic fractures with no abnormalities of the ovarian veins. Her inpatient course was uncomplicated other than a sustained, isolated raised C reactive protein. CT of the abdomen 1 week after injury demonstrated stable solid organ injuries and the additional, unexpected finding of a right ovarian vein thrombosis (OVT). A pragmatic approach was taken towards the management of the OVT given the haemorrhagic risk from her traumatic injuries. A multidisciplinary, consultant-led plan was made to slowly increase enoxaparin to a therapeutic dose under close surveillance and to then switch to warfarin following an outpatient consultation with a consultant haematologist. A MR venogram was performed after 3 months of anticoagulation, and this demonstrated complete resolution of the OVT and normal appearances of the ovary.

Background

This paper describes the first reported case of ovarian vein thrombosis (OVT) secondary to trauma. OVT is most commonly found in the postpartum patient,1 2 however, other aetiologies include pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), gynaecological malignancy, pelvic surgery, sepsis and hypercoagulable states.3 There have also been a handful of case reports describing idiopathic OVT worldwide.3

OVT is a rare condition occurring in 1/600–1/2000 pregnancies4 5 and is diagnosed on the right side in 70–90% of cases.6 7 Presentation is usually with vague lower quadrant abdominal pain and, occasionally, a palpable mass.

Left untreated, OVT can have potentially fatal consequences as pulmonary embolus develops in 25% of cases; other sequelae include ovarian infarction and sepsis.8 Overall, the associated mortality of OVT is 4%, although the highest rates of death are in cases associated with malignancy.8 9

Management is with anticoagulation, although there are no national or internationally recognised guidelines for length of treatment or surveillance.2

Case presentation

A 24-year-old mother of three presented to a major trauma centre as a trauma alert following a medium-speed road traffic collision. Prehospitally, the patient received no tranexamic acid as she had no evidence of haemodynamic compromise. She remained haemodynamically stable throughout the remainder of her resuscitation and received no blood products. She underwent a ‘CT traumagram’, of which our unit protocol includes a plain head scan followed by angiogram from the Circle of Willis to the lesser trochanters as a biphasic injection.

The patient was normally fit and well, a non-smoker with a body mass index of 27. She had three healthy children via normal vaginal delivery and had no history of miscarriage. There was no significant family history and no risk factors identified for PID.

The patient's injuries included a grade 1 liver laceration, grade 1 right renal laceration, a small amount of physiological free fluid in the pelvis, L4 and 5 transverse process fractures, and right superior and inferior pubic rami fractures.

She was admitted to the ward under the Major Trauma Service team for analgaesia and observation. On admission, she was prescribed antiembolism stockings and started on prophylactic enoxaparin (40 mg once daily) at 24 h, as per hospital protocol.

She was kept in hospital for observation and physiotherapy assessment. The local liver surgery protocol is to perform interval CT liver scans at 1 week postinjury to identify any evidence of pseudoaneurysm, and so the patient was kept as an inpatient until this occurred. She remained pain free from all injuries and began protected weight-bearing with the physiotherapy team after 2 days.

Investigations

The patient's observations were within normal physiological limits throughout her entire stay. All blood tests were normal other than an isolated raised C reactive protein (CRP), which remained between 317 and 337, and continued to be raised until treatment of the OVT began. Investigations were conducted to identify a cause for the raised CRP; no evidence of infection or systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) response was found.

After 1 week, an interval liver CT demonstrated stable liver and renal lacerations with no evidence of post-traumatic pseudoaneurysms or fistulae. However, the CT did reveal a right OVT not previously evident on the patient's initial CT traumagram (figures 1 and 2). These images were reviewed by a consultant gynae-radiologist at the local Women's Hospital and the findings verified.

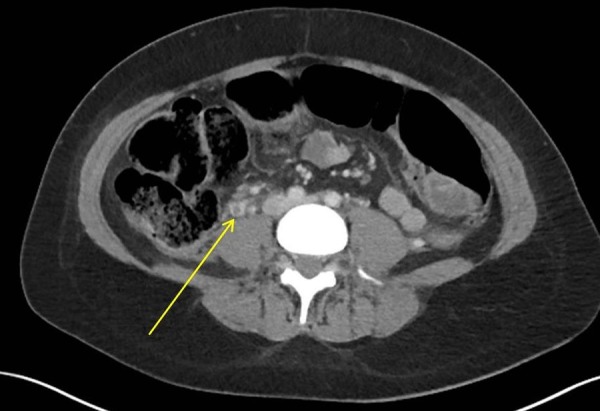

Figure 1.

Axial view demonstrating right OVT. OVT, ovarian vein thrombosis.

Figure 2.

Coronal view 1 demonstrating right ovarian vein thrombus.

Antiphospholipid screen performed following diagnosis of OVT was negative.

Differential diagnosis

The patient appeared clinically well. She improved every day, in terms of her mobility, and suffered minimal levels of pain from her injuries throughout her stay. The clinical team was concerned about the isolated raised CRP as it was unusually high without any obvious cause, and with no associated rise in white cell count and no fever. Chest examination and radiograph ruled out lower respiratory tract infection and, following removal of the catheter, all urine dips were negative for signs of infection. The patient had no traumatic wounds as possible sources for infection.

Treatment

The risk of haemorrhage from the solid organ injuries was discussed with the relevant teams at consultant level. Despite the stable appearance of the liver laceration, the liver surgery team felt a cautious approach to anticoagulation was required. A treatment plan was devised by the haematology team, and agreed on by the liver surgeons and urologists. The eventual management was a gentle escalation of enoxaparin to 40 mg two times a day, followed by an increase to the full therapeutic dose while being monitored as an inpatient. On discharge, therapeutic enoxaparin was continued for 1 month before switching to warfarin following a consultant haematology clinic appointment. The full and total course of anticoagulation treatment was given for 3 months. In cases of postpartum OVT, most papers advocate the use of broad-spectrum due to the presumptive diagnosis of endometritis.10 However, following discussion with the local gynaecology team, there was a consensus decision that in this case no antimicrobial therapy was indicated. The patient developed no infective complications throughout her course of treatment and recovery.

Outcome and follow-up

A repeat outpatient CT liver was requested by the liver surgeons 4 weeks postdischarge, which demonstrated vast improvement of the liver laceration with no evidence of haemorrhagic complication from the anticoagulation. The patient was also followed up by the urology team in clinic, with a dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) renal scan showing equal split function and no evidence of extravasation. A MR venogram (MRV) was performed at 3 months, after completion of a full course of anticoagulation. The MRV demonstrated a normal flow void within the right ovarian vein and normal appearances of the ovary, suggesting appropriate vascularisation. In addition to the aforementioned imaging, the patient was brought back to anticoagulation clinic 1 month after discharge, where she was counselled and converted to warfarin therapy. She was also seen in the Major Trauma Service clinic, where she reported no issues with pain and was noted to be mobilising well.

Discussion

Already a rare diagnosis, OVT in this patient was an unexpected and incidental radiological finding. At our unit, we regularly rescan patients with solid organ injuries after a set period of time, however, we rarely perform repeat CTs on patients with pelvic injuries. It may be the case that women have gone undiagnosed with this condition.

An OVT has been previously described in patients following pelvic surgery, and similar pathological processes could be occurring to produce an OVT in a trauma patient. It would be detrimental to suggest that every female trauma patient with pelvic injuries should receive a CT. However, it may be pertinent for patients diagnosed with an ‘idiopathic’ OVT that a full history should include specific questions about recent injuries, including any history of domestic violence.

A well-known risk factor for development of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is that of reduced mobility. This is a risk factor that is commonly shared with trauma patients who may be put on bed rest for spinal injury or who may find mobilising difficult due to pain issues or lower limb fractures. In this case, although the patient began mobilising with physiotherapists within 48 h of admission, her prescription was that of ‘protected’ weight-bearing and would therefore have been considerably reduced compared to her normal daily level of activity for a young mother of 3. This reduced level of mobility, leading to venous stasis, may well have been a contributing factor in the development of an ovarian vein clot.

Currently, there is no national or international guideline for treatment of OVT. A 2006 review of OVT cases in America discovered that the recurrence rate of OVT is similar to that of lower limb DVT and the paper therefore suggested that treatment should mirror that of lower limb DVT management.9 A complicating factor in trauma patients with OVT is weighing up the risk of thrombus extension versus haemorrhage from existing sites of injury. This case was handled with a multidisciplinary approach at consultant level involving the Major Trauma Service, Urology, Liver Surgery, Radiology and Haematology consultants. The patient was at all times kept under close observation and it was ensured following discharge that she had regular follow-up and imaging with the management teams.

Learning points.

Trauma can be a cause of ovarian vein thrombosis (OVT) in female patients with pelvic injuries.

Thrombotic events should be considered as a cause for isolated raised C reactive protein where there is no evidence of infection.

Reduced mobility and bed rest following trauma is a potential risk factor in the development of OVT.

In cases of ‘idiopathic’ OVT, a full history should include questions to identify any episodes of trauma, including domestic abuse, which will often not be disclosed without specific and tactful questioning.

Risk of bleeding versus risk of thrombotic events provides an additional layer of complexity when considering treatment of OVT in traumatic cases.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the patient and her family for providing consent to write up this case for publication. Many thanks for your understanding in the difficulties we encountered while developing a management plan for your unique condition.

Footnotes

Contributors: ET highlighted the potential for write up. ET, AB, MB and KP contributed to design, content and write up. MB chose and reviewed the images included. All the authors contributed to refinement of the report and approved the paper prior to submission.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Heavrin BS, Wrenn K. Ovarian vein thrombosis: a rare cause of abdominal pain outside the peripartum period. J Emerg Med 2008;34:67–9. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.05.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simons GR, Piwnica-Worms DR, Goldhaber SZ. Ovarian vein thrombosis. Am Heart J 1993;126(3 Pt 1):641–7. 10.1016/0002-8703(93)90415-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stafford M, Fleming T, Khalil A. Idiopathic ovarian vein thrombosis: a rare cause of pelvic pain—case report and review of literature. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2010;50:299–301. 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2010.01159.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunnihoo DR, Gallaspy JW, Wise RB et al. Postpartum ovarian vein thrombophlebitis: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1991;46:415–27. 10.1097/00006254-199107000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ortin X, Ugarriza A, Espax RM et al. Postpartum ovarian vein thrombosis. Thromb Haemost 2005;93:1004–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baran GW, Frisch KM. Duplex Doppler evaluation of puerperal ovarian vein thrombosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1987;149:321–2. 10.2214/ajr.149.2.321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prieto-Nieto MI, Perez-Robledo JP, Rodriguez-Montes JA et al. Acute appendicitis-like symptoms as initial presentation of ovarian vein thrombosis. Ann Vasc Surg 2004;18:481–3. 10.1007/s10016-004-0059-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris K, Mehta S, Iskhakov E et al. Ovarian vein thrombosis in the nonpregnant woman: an overlooked diagnosis. Ther Adv Hematol 2012;3:325–8. 10.1177/2040620712450887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wysokinska EM, Hodge D, McBane RD II. Ovarian vein thrombosis: incidence of recurrent venous thromboembolism and survival. Thromb Haemost 2006;96:126–31.16894453 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jenayah AA, Saoudi S, Boudaya F et al. Ovarian vein thrombosis. Pan Afr Med J 2015;21:251 10.11604/pamj.2015.21.251.6908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]