Abstract

Colorectal cancer is a common malignant neoplasm and its treatment usually involves surgery associated, in some cases, depending on the staging, with chemoradiotherapy. Necrotising fasciitis of the perineum is a highly lethal infection of the perineum, perirectal tissues and genitals, requiring emergency surgical debridement, broad-spectrum antibiotics and control of sepsis. We present the case of a 59-year-old man with necrotising fasciitis of the perineum as the first clinical manifestation of locally advanced adenocarcinoma of the rectum, in which successful management consisted of early and aggressive surgical debridement, followed by multimodal therapy with curative intent. 2 years and 6 months after surgery the patient is well, with no evidence of local or systemic relapse.

Background

Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in Europe.1 Clinical presentation is usually characterised by hematochezia, tenesmus and change in bowel habits. Surgical resection with total mesorectum excision is the mainstay of therapy.2 3 Chemoradiotherapy plays an important role in down-sizing, down-staging and reducing the risk of local relapse.2 3

Necrotising fasciitis of the perineum is a rare, rapidly progressive and highly lethal infection of the perineum, perirectal tissues and genitals.4–15 It is usually associated with perianal or colorectal conditions, such as perianal abscess. Treatment consists of broad-spectrum antibiotics and aggressive surgical debridement.4–15

Necrotising fasciitis of the perineum as the first clinical manifestation of locally advanced adenocarcinoma of the rectum is a rare event.8–15 The authors present such a case, in which successful management consisted of early and aggressive surgical debridement of infected tissues, followed by multimodal therapy with curative intent.

Case presentation

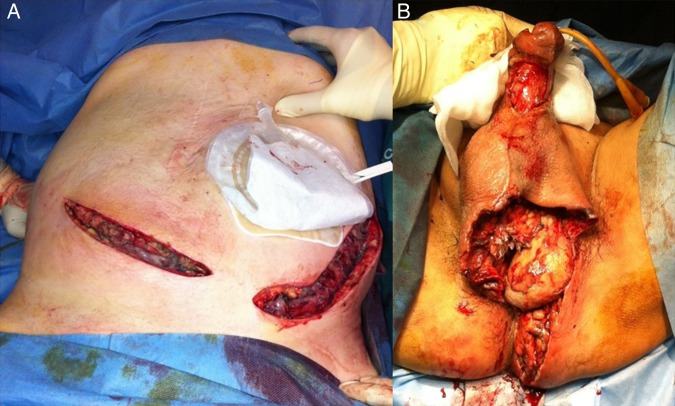

A 59-year-old man presented to the emergency department, with a history of severe pain and tenderness of the lower abdomen, scrotum, genitalia and perineum. He also reported asthenia, weight loss, anorexia, rectal bleeding and tenesmus for the past 12 weeks. The medical history was negative. Physical examination revealed cellulitis of the lower abdomen, penis, scrotum, perineum and buttocks, with isolated dispersed necrotic areas (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Physical examination demonstrating extensive inflammation with areas of necrosis.

He had no fever and was haemodynamically normal. Laboratory findings showed an elevated leucocyte count (13.7×109/L (normal value: 4.0–10.0×109/L)) and C reactive protein (2699 mg/dL (normal value: <0.5 mg/dL)), with a laboratory risk indicator for necrotising fasciitis score of 7. Empirical broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy was started and the patient was taken to the operating theatre. After general anaesthesia, a rectal circumferential mass, at 3 cm of the anal margin, was identified on digital rectal examination. Excisional debridement of the lower abdominal wall, penis, scrotum and buttocks was performed. Sigmoid loop colostomy and rectal mass biopsy were also carried out at this stage (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Surgical debridement and faecal diversion with loop colostomy.

Tissue cultures later yielded Escherichia coli, Streptococcus viridans, Peptostreptococcus micros and Fusobacterium nucleatum. Postoperatively, vacuum-assisted wound closure (VAC) (KCI International Inc, Amstelveen, The Netherlands) was used with satisfactory evolution. The patient was discharged on the 39th postoperative day.

Investigations

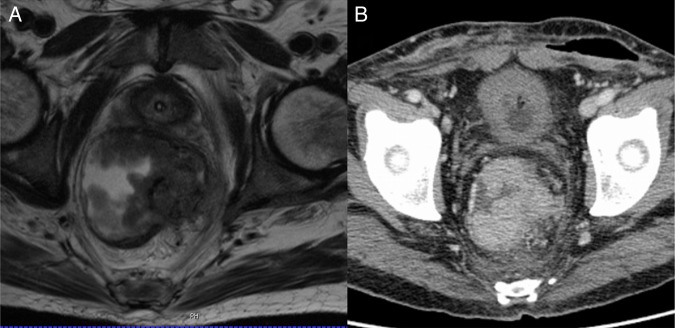

Rectal biopsy identified a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma. The patient was staged with thoracic and abdominal CT and pelvic MRI as T4bN+M0 (figure 3). Invasion of the pelvic floor and extra-rectal tissues was diagnostic of a T4 tumour.

Figure 3.

MRI and CT demonstrating a large rectal tumour with invasion of the pelvic floor and extra-rectal tissues (T4b in Tumor, Nodes and Metastasis (TNM) classification).

Treatment

The patient underwent neo-adjuvant short-term radiation (25 Gy/5 days) therapy. The choice of not performing long-term chemoradiation therapy was due to the fact that the patient presented with large tissue defects and maintained wound dressings as an outpatient. He returned to the operating theatre 8 weeks later and abdominoperineal resection and end colostomy were performed. Final pathology staging was ypT3N0 (in 35 lymph nodes) with negative margins. Perineal and abdominal surgical wound site infections were diagnosed on day 5, and VAC was again used, with the patient being discharged on the 29th postoperative day. He maintained wound dressings in the outpatient clinic with ultimately satisfactory healing.

Outcome and follow-up

Two years and 6 months after surgical resection, the patient is alive and well, with no clinical, biological or radiological signs of local or systemic relapse.

Discussion

Necrotising fasciitis of the perineum is a rare presentation of advanced rectal cancer.14 Since necrotising fasciitis is more common in elderly and immunocompromised patients, and carries high mortality,4 7 and because rectal cancer is usually in the perforated stage, aggressive curative-intent therapy is often not possible.9 13 15 The case we present illustrates the need for immediate life-saving control of local sepsis (wide debridement and faecal diversion), followed by vacuum-assisted closure. Adequate staging and successful multimodal therapy followed, allowing long-term, relapse-free survival.

Learning points.

Necrotising fasciitis of the perineum can be the first clinical presentation of locally advanced rectal cancer; diagnosis usually depends on the finding of a rectal mass.

Treatment of perineal sepsis usually depends on early and aggressive surgical debridement of the skin and soft tissues, along with broad-spectrum antibiotics and supportive care; faecal diversion is usually mandatory.

After resolution of sepsis, treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer depends on proper staging; curative treatment should be pursued with the combination of surgery and chemoradiotherapy.

Footnotes

Contributors: LF collected the data, performed the literature search, wrote the manuscript and reviewed the final version. HA collected the data, wrote the manuscript and reviewed the final version. JSL and FCS critically reviewed the final version.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL et al. . Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:87–108. 10.3322/caac.21262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benson AB, Venook AP, Bekaii-Saab T et al. . Rectal Cancer, Version 2.2015. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2015;13:719–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee M, Gibbs P, Wong R. Multidisciplinary management of locally advanced rectal cancer—an evolving landscape? Clin Colorectal Cancer 2015;14:251–61. 10.1016/j.clcc.2015.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eke N. Fournier's gangrene: a review of 1726 cases. Br J Surg 2000;87:718–28. 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01497.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozden Yeniyol C, Suelozgen T, Arslan M et al. . Fournier's gangrene: experience with 25 patients and use of Fournier's gangrene severity index score. Urology 2004;64:218–22. 10.1016/j.urology.2004.03.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Estrada O, Martinez I, Del Bas M et al. . Rectal diversion without colostomy in Fournier's gangrene. Tech Coloproctol 2009;13:157–9. 10.1007/s10151-009-0474-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yaghan RJ, Al-Jaberi TM, Bani-Hani I. Fournier's gangrene: changing face of the disease. Dis Colon Rectum 2000;43:1300–8. 10.1007/BF02237442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta PJ. Rectal cancer presenting as ischio-rectal abscess and Fournier's gangrene—a case report. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2010;14:139–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajendran S, Khan A, Murphy M et al. . Rectocutaneous fistula with Fournier's gangrene, a rare presentation of rectal cancer. BMJ Case Rep 2011;2011:pii: bcr0620114372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moslemi MK, Sadighi Gilani MA, Moslemi AA et al. . Fournier gangrene presenting in a patient with undiagnosed rectal adenocarcinoma: a case report. Cases J 2009;2:9136 10.1186/1757-1626-2-9136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gamagami RA, Mostafavi M, Gamagami A et al. . Fournier's gangrene: an unusual presentation for rectal carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:657–8. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.189_b.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elgin Y, Demirkasimoglu T, Kucukplakci B et al. . Anal tumor diagnosed after the recovery of Fournier gangrene [2]. Dig Dis Sci 2006;51:889–90. 10.1007/s10620-006-9098-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ash L, Hale J. CT findings of perforated rectal carcinoma presenting as Fournier's gangrene in the emergency department. Emerg Radiol 2005;11:295–7. 10.1007/s10140-005-0417-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bruketa T, Majerovic M, Augustin G. Rectal cancer and Fournier's gangrene—current knowledge and therapeutic options. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:9002–20. 10.3748/wjg.v21.i30.9002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khalil H, Tsilividis B, Schwarz L et al. . Necrotizing fasciitis of the thigh should raise suspicion of a rectal cancer. J Visc Surg 2010;147:e187–9. 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2010.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]