Abstract

Purpose:

Benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS) is considered to be the most common childhood epileptic syndrome. We studied the relationship between the type of seizures and response to medication in a Greek population.

Materials and Methods:

We studied 60 neurodevelopmentally normal children diagnosed with BECTS. Children were subdivided into three groups, based on type of seizures: Group A comprised 32 children with generalized tonic-clonic seizures, Group B 19 children with focal seizures and Group C 9 children with focal seizures with secondary generalization. All patients in the present study were started on an antiepileptic medication after the third seizure (sodium valproate, carbamazepine, and oxcarbazepine), and we studied the response to medication.

Results:

10 from 13 (76.92%) of patients in Group A, 13 from 15 (86.66%) patients in Group B, and all 6 patients (100%) in Group C started carbamazepine or oxcarbazepine had a favorable respond. Similarly, 16 from 19 (84.2%) of patients in Group A, 3 from 4 patients (75%) in Group B, and 1 from 3 patients (33.3%) in Group C, started sodium valproate responded well to medication.

Conclusions:

The majority of children responded well to the first antiepileptic treatment and had a favorable outcome, regardless of type of seizures. 88.3% of children became seizure free by 1 or 2 years after seizure onset. These findings are indicative that the type of seizures has no major effect neither in response to antiepileptic treatment or in the final outcome. Further research in a larger number of children is needed.

Keywords: Benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes, medication, response, children

Introduction

Epilepsy is a common condition in childhood, characterized by chronic seizures as a result of excessive, synchronous discharge of cerebral neurons. The onset of seizures in more than 50% of cases occurs in childhood, with the prevalence from 0.7% to 1%.[1] In Greece, the number of people with epilepsy is approximately 60.000–70.000.[2] There are many epileptic syndromes which have been subdivided into groups, based on clinical presentation, neuropsychomotor development, neurological examination, electroencephalogram (EEG), and magnetic resonance imaging findings.[3]

Benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS) is considered to be the most common childhood epileptic syndrome placed among the idiopathic localization-related epilepsies, accounting for 8–20% of pediatric patients with epilepsy.[4,5] It has a characteristic age of onset, neurodevelopmental profile, seizure, imaging, and electroencephalographic pattern. The age of onset ranges from 1 to 14 years with 75% starting between 7 and 10 years. Classically, BECTS occurs in neurodevelopmentally normal children. Ictal manifestations occur more frequently (75%) during nonrapid eye movement sleep, mainly at sleep onset or just before awakening. The seizures are usually brief lasting for 1–3 min. Seizures are somatosensory and motor focal, mainly affecting the face and oropharynx, with the speech arrest and hypersalivation and in some cases involving the upper limb. The characteristic EEG shows high voltage spikes or spike and waves in the centrotemporal region (CTSs) that may shift from side to side with a normal background. Neuroimaging is normal. Children become seizure free by the age of 14, with normalization of the EEG and without neurological deficits. Carbamazepine or oxcarbazepine is considered to be the first line drug of choice, although some children with BECTS (infrequent seizures, mild or nocturnal, onset close to the natural age of remission) do not need antiepileptic therapy.[6,7]

The prospective study objective was to describe the relationship between the type of seizures and response to medication in Greek children diagnosed with BECTS.

Materials and Methods

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

The study was approved by the competent Research Ethics Committee. Each participant provided written informed consent prior to study enrollment.

Study group and methods

60 individuals (mean age at diagnosis: 9.4 years; 26 males, 34 females) diagnosed with BECTS in our department were enrolled in this study. For inclusion, the children attended the following criteria defined by the International League Against Epilepsy:[8] (i) At least one witnessed seizure with typical features: Nocturnal, simple partial seizures affecting one side of the body or on alternate sides; (ii) oro-facialpharyngeal sensorimotor symptoms, with speech arrest and hypersalivation; (iii) age of onset between 3 and 12 years; (iv) no previous epilepsy type; (v) normal global developmental milestones; (vi) normal neurological examination; (vii) at least one interictal EEG with CTS and normal background, verified by two independent and blinded readers; and (viii) neuroimaging read by two independent and blinded board-certified neuroradiologists that excluded an alternative structural, inflammatory or metabolic cause for the seizures.

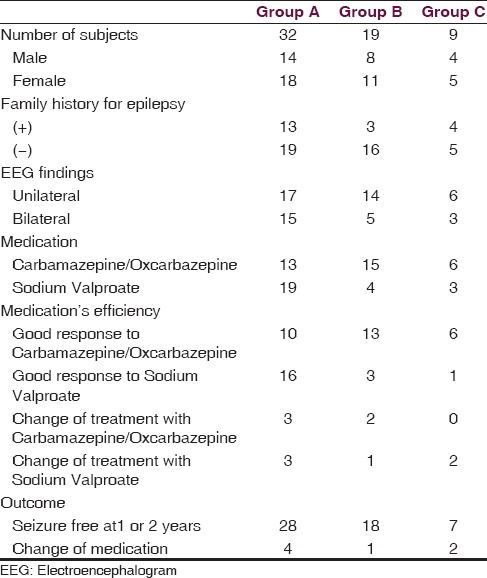

Children were subdivided into three groups, based on type of seizures: Group A comprised 32 children (53.3%) with generalized tonic-clonic seizures (GTCS), Group B 19 children (31.7%) with focal seizures and Group C 9 children (15%) with focal seizures with secondary generalization. All patients in the present study were started on an antiepileptic medication (sodium valproate, carbamazepine, and oxcarbazepine) after a third seizure in a short period of time (2 months) and had clinical, biochemical, and EEG examination every 3 months. Table 1 shows the gender distribution, family history for epilepsy, clinical, and EEG characteristics, medication and outcome of all 60 patients.

Table 1.

Clinical and EEG characteristics, medications and outcome (n=60)

Sixteen-channel EEG recording was performed for all patients both during sleep states and during wakefulness. Electrodes were placed using the 10–20 International System with bipolar and referential montages. Hyperventilation and intermittent photic stimulation from 1 to 30 Hz was performed during each EEG recording that lasted at least 30 min. In the present study, only EEGs during wakefulness were undertaken.

Results

Of total 60 patients with BECTS, 32 children (53.3%) had GTCS (Group A), 19 children (31.7%) had focal seizures (Group B), and 9 children (15%) had focal seizures with secondary generalization (Group C).

The EEG of all patients revealed high voltage spikes or spike and waves in the centrotemporal region (CTSs). Of a total of 60 patients, 37 children (61.7%) exhibited unilateral findings on EEG, either on the right or left hemisphere and 23 children (38.3%) had bilateral EEG findings.

All patients in the present study were started on an antiepileptic medication (sodium valproate, carbamazepine, and oxcarbazepine) after a third seizure in a short period of time (2 months). Of total 60 patients, 29 children (48.3%) responded well to treatment with carbamazepine or oxcarbazepine and 20 children (33.3%) responded well to sodium valproate. Five children (8.3%) started treatment with carbamazepine or oxcarbazepine but due to incomplete control of seizures they had to change medication. Six children (10%) started treatment with sodium valproate but due to uncontrollable seizures they had to change medication.

According to medication's efficiency, 53 children (88.3%) became seizure free by 1 or 2 years after seizure onset while 7 children (11.7%) had to change medication due to uncontrollable seizures. All 53 children (28 from Group A, 18 from Group B and 7 from Group C) who became seizure free by 1 or 2 years after seizure onset were under the age of 16 years (we clarify that because it's well known that remission usually occurs after 2–4 years of onset and before the age of 16 years).

With regard to type of seizures and medication's efficiency, 10 from 13 patients (76.92%) in Group A, 13 from 15 patients (86.66%) in Group B, and all 6 patients (100%) in Group C started carbamazepine or oxcarbazepine had a favorable respond. Similarly, 16 from 19 patients (84.2%) in Group A, 3 from 4 (75%) patients in Group B, and 1 from 3 children (33.3%) in Group C, started sodium valproate responded well to medication.

Three patients from Group A and 2 patients from Group B started with carbamazepine or oxcarbazepine had to change medication due to the incomplete control of seizures. Similarly, 3 patients from Group A, one from Group B, and 2 from Group C started sodium valproate had to change their antiepileptic therapy due to the incomplete control of seizures.

Discussion

BECTS is one of the most frequent epileptic syndromes in children. At the present prospective study, we present the clinical and EEG characteristics, medications, and outcome of 60 Greek children diagnosed with BECTS. More specifically we describe the relationship between the type of seizures and response to medication in our study group.

In total, three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and no metaanalyses specifically examined the initial monotherapy of children with BECTS. None of these RCTs met the criteria for a class I or II study. No antiepileptic drug medication reaches the highest levels of evidence (level A or B) for efficacy/effectiveness for children with BECTS, while carbamazepine and valproic acid are possibly efficacious or effective as initial monotherapy for children with BECTS (level C).[9,10,11] In the international literature, there have been few studies for determining the risk factors affecting failure to respond to the initial antiepileptic treatment in children with BECTS.[12,13] In a more recent study by Incecik et al., in an effort to determine the risk factors associated with a poor prognosis in children with BECTS, they reached to the conclusion that younger age of seizure onset, presence of generalized seizures, and frequent seizures (>3 prior to the initial treatment) were associated with failure to control seizures with the initial antiepileptic treatment.[14] In their study, authors detected 14.3% of children is not responding successfully to the first antiepileptic treatment. In our study, the majority of children responded well to the first antiepileptic treatment (sodium valproate, carbamazepine or oxcarbazepine). More specifically, 81.25% (26 from 32) of patients in Group A (GTCS), 84.21% (16 from 19) in Group B (focal seizures), and 77.77% (7 from 9) in Group C (focal seizures with secondary generalization) responded well to the first antiepileptic treatment.

Most studies reported that a family history is present in 10–59% of children with BECTS.[15,16,17] In our study, family history of epilepsy was noted in 33.3% of our patients, it is similarly with literature.

Children with BECTS typically present with partial seizures. In previous studies, Zhao et al. reported 82.2% partial seizures, 19.9% secondary generalized seizures, and 17.8% primary generalized seizures. Bouma et al. reported 43.5% secondarily generalized seizures.[17,18] These figures are significantly higher than the frequency of 20–35% of secondarily generalized seizures described earlier by Aicardi and by Lerman and Kivity.[19,20] Incecik et al., reported 70.2% partial seizures, 23.8% secondary generalized seizures while 6% had primary generalized seizures at first. In our study, 32 children (53.3%) had GTCS, 19 children (31.7%) had focal seizures, and 9 children (15%) had focal seizures with secondary generalization.

The classical EEG presentation of BECTS shows normal or basically normal background with high voltage diphasic spikes or sharp waves in the centrotemporal area. Lerman and Kivity reported that approximately 60% of seizures had a unilateral focus, whereas 40% show bilateral lesions.[21] Ma and Chan found that 75% of the spikes had a unilateral focus, while 24.7% a bilateral one.[16] In a more recent study by Incecik et al., 83.3% of EEG discharges were unilateral, whereas 16.7% were bilateral. Our results are similar to international literature, with 61.7% of children with BECTS have unilateral EEG discharges and 38.3% bilateral.

Based on the results of the present study, we conclude that the majority of children responded well to the first antiepileptic treatment (sodium valproate, carbamazepine, or oxcarbazepine), regardless to the type of seizures. Besides, the outcome was favorable for most of the children enrolled in this study, regardless the seizure type, with 88.3% of children becoming seizure free by 1 or 2 years after seizure onset, while only 11.7% in need to change medication due to uncontrollable seizures. These findings are indicative that the type of seizures has no major effect neither in response to antiepileptic treatment or in the final outcome.

The limitation of our study is the small number of children enrolled. Further research in a larger number of children is needed to evaluate the possible relationship between the type of seizures and response to medication in children with BECTS.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Cowan LD. The epidemiology of the epilepsies in children. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2002;8:171–81. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.10035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camfield P, Camfield C. Epileptic syndromes in childhood: Clinical features, outcomes, and treatment. Epilepsia. 2002;43(Suppl 3):27–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.43.s.3.3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pazzaglia P, D’Alessandro R, Lozito A, Lugaresi E. Classification of partial epilepsies according to the symptomatology of seizures: Practical value and prognostic implications. Epilepsia. 1982;23:343–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1982.tb06200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holmes GL. Benign focal epilepsies of childhood. Epilepsia. 1993;34(Suppl 3):S49–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.1993.tb06259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wirrell EC. Benign epilepsy of childhood with centrotemporal spikes. Epilepsia. 1998;39(Suppl 4):S32–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb05123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Neuropsychological effects of epilepsy and antiepileptic drugs. Lancet. 2001;357:216–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03600-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hauser WA, Annegers JF, Rocca WA. Descriptive epidemiology of epilepsy: Contributions of population-based studies from Rochester, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:576–86. doi: 10.4065/71.6.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Proposal for revised classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes. Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1989;30:389–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1989.tb05316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rating D, Wolf C, Bast T. Sulthiame as monotherapy in children with benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes: A 6-month randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Sulthiame Study Group. Epilepsia. 2000;41:1284–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb04606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitsudome A, Ohfu M, Yasumoto S, Ogawa A, Hirose S, Ogata H, et al. The effectiveness of clonazepam on the rolandic discharges. Brain Dev. 1997;19:274–8. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(97)00575-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bourgeois B, Brown LW, Pellock JM, Buroker M, Greiner M, Garofalo EA. Gabapentin (Neurontin) monotherapy in children with benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS): A 36-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Epilepsia. 1998;39:163. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kramer U, Zelnik N, Lerman-Sagie T, Shahar E. Benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes: Clinical characteristics and identification of patients at risk for multiple seizures. J Child Neurol. 2002;17:17–9. doi: 10.1177/088307380201700104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.You SJ, Kim DS, Ko TS. Benign childhood epilepsy with centro-temporal spikes (BCECTS): Early onset of seizures is associated with poorer response to initial treatment. Epileptic Disord. 2006;8:285–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Incecik F, Altunbasak S, Herguner OM, Mert G, Sahan D. Prognostic significance of failure of the initial antiepileptic drug in children with benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. Brain Dev. 2015;37:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holmes GL. Rolandic epilepsy: Clinical and electroencephalographic features. Epilepsy Res Suppl. 1992;6:29–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma CK, Chan KY. Benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes: A study of 50 Chinese children. Brain Dev. 2003;25:390–5. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(03)00003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bouma PA, Bovenkerk AC, Westendorp RG, Brouwer OF. The course of benign partial epilepsy of childhood with centrotemporal spikes: A meta-analysis. Neurology. 1997;48:430–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.2.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao X, Chi Z, Chi L, Shang W, Liu X. Clinical and EEG characteristics of benign rolandic epilepsy in Chinese patients. Brain Dev. 2007;29:13–8. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aicardi J. Benign rolandic epilepsy. Int Pediatr. 1987;2:176–81. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lerman P, Kivity S. Benign focal epilepsy of childhood. A follow-up study of 100 recovered patients. Arch Neurol. 1975;32:261–4. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1975.00490460077010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lerman P, Kivity S. The benign focal epilepsies of childhood. In: Pedley TA, Meldrum BS, editors. Recent Advances in Epilepsy. Vol. 3. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingston; 1986. pp. 137–56. [Google Scholar]