Abstract

Influenza A virus (IAV) infection causes seasonal epidemics of contagious respiratory illness that causes substantial morbidity and some mortality. Regular vaccination is the principal strategy for controlling influenza virus, although vaccine efficacy is variable. IAV antiviral drugs are available; however, substantial drug resistance has developed to two of the four currently FDA-approved antiviral drugs. Thus, new therapeutic approaches are being sought to reduce the burden of influenza-related disease. A high-throughput screen using a human kinase inhibitor library was performed targeting an emerging IAV strain (H7N9) in A549 cells. The inhibitor library contained 273 structurally diverse, active cell permeable kinase inhibitors with known bioactivity and safety profiles, many of which are at advanced stages of clinical development. The current study shows that treatment of human A549 cells with kinase inhibitors dinaciclib, flavopiridol, or PIK-75 exhibits potent antiviral activity against H7N9 IAV as well as other IAV strains. Thus, targeting host kinases can provide a broad-spectrum therapeutic approach against IAV. These findings provide a path forward for repurposing existing kinase inhibitors safely as potential antivirals, particularly those that can be tested in vivo and ultimately for clinical use.

Introduction

Influenza type A virus (IAV) infections in humans result in an estimated 200,000 hospitalizations and between 30,000 and 50,000 deaths in the United States annually and many thousands more globally.1–3 In April 2013, a new IAV strain, H7N9, emerged in China4 causing considerable concern because it carried a high (>20%) mortality rate in humans and because of the uncertain mode of transmission. Unlike the avian H5N1 viruses, which contain a neuraminidase subtype (N1) that is also present in the annual, seasonal, human virus strains, this novel avian virus contains a hemagglutinin (H7) and a neuraminidase (N9) that have not previously circulated in the human population.5,6 Thus, the world's population is essentially immunologically naive, making this virus a candidate for a pandemic strain.

Vaccination is the principal strategy for controlling influenza disease and is implemented annually. Vaccine composition varies as a result of global surveillance data, and new vaccines to highly pathogenic avian influenza strains, H5N1 or H7N9, are developed based on the perceived threat to global health. However, vaccine efficacy is notoriously variable, particularly in the populations at greatest risk of complications from the influenza virus infection, such as the young and elderly.7 Of note, despite increasing vaccination rates, influenza-related hospitalizations are increasing,7,8 suggesting a need for supplemental control.

Influenza antiviral drugs are an important adjunct to vaccination. However, substantial drug resistance to the current antivirals, which target the viral M2 ion channel (amantadine and rimantadine) or neuraminidase, (NA) (such as zanamivir, oseltamivir, and peramivir) has developed.9,10 The current limitations in approved antiviral drugs and increasing development of drug resistance emphasize the need to add more tools to the antiviral toolbox.

The development of new therapeutic drugs is a cumbersome and extremely time- and resource-consuming process fraught with more failure than success. The typical drug development program takes 10–15 years to complete and costs a billion dollars or more for the final product to reach the clinic where it may fail FDA approval.11–13 The time-consuming nature and high failure rate are especially concerning the development of therapeutics for emerging and re-emerging diseases such as the influenza virus.

One option that would allow for more rapid therapeutic drug availability involves repurposing available compounds or previously approved drugs. This process makes use of existing drugs that have been either successfully approved to treat unrelated diseases or drugs having known safety profiles in preclinical or clinical studies, but fell out of the pipeline because of insufficient efficacy for their target, which is often cancer.11,14 Repurposing of drugs that have already passed the initial safety or Phase I studies would allow them to directly enter later stages of clinical trials for new indications such as antiviral. Typically, these drugs become available for clinical use in 2 years compared to the 10–15-year period required for standard drug development methods. Importantly, this accelerated path trims >40% of the costs associated with standard drug development.11,12,15

Several studies, including those from our laboratory, have reported host cellular factors that are seized by IAV for replication.16–21 Targeting proviral host factors represents a therapeutic strategy for the influenza infection. Due to the relative stability of host gene targets compared to influenza viral targets, targeting host genes also offers an innovative approach to limit drug resistance and likely possess a broad-spectrum antiviral activity against various strains of IAV.22

Our laboratory and others had identified key host factors, particularly host cell kinases that support IAV replication.17–19,23,24 This is not unexpected as kinases have an important role in many aspects of cellular processes, particularly in signal transduction, inflammation, and immunity, making them attractive therapeutic targets.25–27 Furthermore, kinases represent one-quarter of the druggable genome.28 Thus, repurposing existing drugs that target kinases is a significant and practicable therapeutic disease intervention strategy.28,29 Kinase targeting has been extensively explored for novel drug discovery and cancer therapeutics. Most kinase inhibitors target the adenosine triphosphate binding site, preventing its kinase activity to phosphorylate their particular substrate molecules.30

Although a handful of proviral host kinases have been identified, the use of kinase inhibitor for antiviral indication has not been extensively explored. An earlier study described the use of a broad-spectrum kinase inhibitor to block influenza viral RNA synthesis.31–33 However, several reports have shown that kinase inhibitors that act more specifically, such as against MEK (also known as the mitogen-activated protein kinase MAP2K or MAPKK) and Akt (also known as protein kinase B or PKB), are also able to limit the replication of influenza virus.34,35

To explore the potential use of other kinase inhibitors as novel IAV therapeutics, a high-throughput screening (HTS) was performed using a library containing a unique collection of 273 structurally diverse, medicinally active, and cell permeable kinase inhibitors for their activity against a recently emerging H7N9 IAV strain, A/Anhui/1/13 in human alveolar epithelial cells. A number of inhibitors in this library are already in various stages of clinical trials, with several drugs already approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of various diseases. Importantly, supporting bioactivity and safety data are readily available for these inhibitors by previous preclinical and/or clinical studies.

Using this HTS kinase inhibitor screening, several drugs were found to be highly active to suppress the H7N9 influenza virus replication with minimal cytotoxicity. These drugs were also found to be efficacious against other strains of IAV, namely a pandemic 2009 (pdmH1N1) strain A/California/04/09 and a H3N2 strain A/Philippines/2/82-X79, representing the two currently circulating IAV subtypes. Thus, our study demonstrated aspects of safety and efficacy of kinase inhibitors, many of which are already at advanced stages of clinical evaluations, which can be potentially repurposed in a timely manner as antiviral therapies against broad strains of influenza virus infection.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Influenza Virus Stocks

Human type II respiratory epithelial (A549) cells (CCL-185) and Madin–Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) cells (CCL-34) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), supplemented with 5% heat inactivated FBS (HyClone) in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2. Influenza viruses A/Anhui/1/2013 (H7N9), A/California/04/09 (pdmH1N1), A/Philippines/2/82-X79 (H3N2), and A/Mississippi/3/01 (wild type and H274Y) were propagated in 9-day-old embryonic chicken eggs and titered in MDCK cells as previously described.36,37 Studies involving the IAV strain A/Anhui/1/2013 (H7N9) were performed under CDC and USDA-approved biosafety level-3 (BSL-3) conditions.

Kinase Inhibitors and HTS

A549 cells were cultured in a 96-well plate at a density of 10,000 cells per well for 24 h. After 24 h, the media were removed, and cells were washed with PBS twice and treated with a library containing a collection of 273 kinase inhibitors (Selleck Chemicals). The inhibitors were diluted in DMEM supplied with 1 μg/mL TPCK-trypsin (Worthington Biochemical) and 0.3% BSA and added to a final inhibitor concentration of 2 μM. The plates were then transferred to a BSL-3 containment facility to be infected with influenza A/Anhui/1/2013 (H7N9). Plates were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01 for 24 h while under drug treatment. The cells were then fixed with methanol:acetone (80:20%) for 10 min and transferred back to a BSL-2 containment facility to undergo immunostaining for cell-based infectivity analysis as detailed below. The activity of each kinase inhibitor to reduce H7N9 infection normalized to DMSO-treated cells was assessed, and z-scores were calculated based on the standard deviation to determine strength of inhibitors' action compared to the rest of inhibitors in the library.38 Negative z-scores indicate kinase inhibitors with antiviral activity against H7N9, while positive scores indicate a proviral activity.

Antiviral Efficacy Assays

Dinaciclib (SCH727965), flavopiridol HCl (Alvocidib), and PIK-75 (Selleck Chemicals) were resuspended in DMSO to make 10 mM stocks. Oseltamivir phosphate (Roche) was resuspended in DMSO to 2 mg/mL. For dose–response virus inhibition experiments, A549 cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) twice and replaced with serum-free DMEM supplied with 1 μg/mL TPCK-trypsin (Worthington Biochemical) and 0.3% BSA before titration of drugs using the Hewlett-Packard (HP) D300 Digital Dispenser (Tecan).39 For all wells, the final DMSO concentration was normalized to 1%. Two hours post-treatment, cells were infected with influenza virus strains at the indicated MOI without removal of drug. At 24 or 48 h postinfection (hpi), infected cell monolayers were fixed and subjected to immunofluorescence staining to determine percentage of cells infected as described below. The MOI and infection time were selected based on the replication kinetic of each virus, where >80% of mock-treated cells were virus positive at the time of fixation. A percentage of virus inhibitions were calculated relative to DMSO-treated cells. The 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of each drug were determined using nonlinear regression on the GraphPad Prism.

Cellular cytotoxicity was evaluated by measuring adenylate kinase release using the ToxiLight BioAssay kit (Lonza). The ToxiLight 100% lysis control set (Lonza) was used to determine the luminescence value that corresponds to the total adenylate kinase (100% cytotoxicity). The drug concentration that resulted in 50% cytotoxicity (CC50) was determined using the nonlinear regression method. Selectivity indices (SI) were calculated to determine efficacy of drugs as the ratio of CC50 to IC50 for the corresponding IAV strain. Culture supernatants were collected for virus titration in MDCK cells. Hemagglutination (HA) assays were performed using turkey RBCs and the virus-infected MDCK cell supernatant as described. HA titers were determined from the highest dilution factor that produced a positive HA reading, and virus titers were calculated as a 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) using the Spearman–Karber formula.37,40

To determine synergistic effects of multiple kinase inhibitors, the HP D300 dispenser was used to dispense two drugs in combination directly onto the cells. Synergism (or antagonism) value of the inhibitors in combination was determined using the MacSynergyII algorithm.41 This method calculates the deviation from the theoretical additive effect of the inhibitors based on the dose–response curves of the individual inhibitor.

Immunofluorescence Staining and High-Content Imaging

Cells were fixed with cold methanol:acetone (80:20) for 10 min, blocked in 3% BSA, and incubated with the mouse anti-IAV nucleoprotein (NP) antibody (ATCC, H16-L10-4R5), followed by incubation with the Alexa Fluor® 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody and DAPI (4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) counterstain (Invitrogen). Fluorescence images were acquired with a Cellomics Arrayscan VTI high-content imaging system (Thermo Scientific), and the percentage of infection was quantified with proprietary image and analytical software as previously described.21 This quantification was performed over each cell's cytoplasmic and nuclear areas.

To perform this analysis, the location of each cell's membrane and cytoplasm was found by first locating and then masking each DAPI-stained nucleus to create a nuclear mask. A second cytoplasmic mask placed an additional 10 pixels outward from the nuclear mask that approximated the location of the cell membrane and corresponding cytoplasmic and nuclear areas. A background level of NP stain was calculated for each plate from three representative images (∼200 cells/image) from three wells that were untreated or infected. A cell was scored as infected if the amount of NP stain in the cytoplasmic mask was greater than the background level plus three standard deviations. Ten thousand cells were assayed for each well.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were done in the GraphPad Prism using one-way ANOVA. Results are presented as means±standard errors (SE). Values of P≤0.05 were considered significant.

Results

HTS of Kinase Inhibitors Against H7N9 Influenza

To evaluate the potential antiviral activity of kinase inhibitors against H7N9 IAV, a library containing 273 kinase inhibitors was screened (Supplementary Fig. S1A; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/adt). Human alveolar basal epithelial A549 cells grown in the 96-well format were treated with the inhibitor collection at a 2 μM final concentration and subsequently infected with influenza A/Anhui/1/13 (H7N9). At 24 hpi, the A549 cells were fixed and stained for viral NP to determine infectivity.

Several kinase inhibitors showed potent inhibitory activity against H7N9 virus replication, including several inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), namely dinaciclib, flavopiridol, and SNS-032, and an inhibitor of p110α/γ forms of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and DNA-PK PIK-75 (Supplementary Fig. S1B and Supplementary Table S1). One of the kinase inhibitors that showed high activity against H7N9 replication in the current screen, flavopiridol, has been previously reported to be efficacious against a laboratory influenza virus strain A/WSN/33 (H1N1), a finding that validates the current screen.42 In contrast, some kinase inhibitors showed proviral activity, enhancing virus replication in cells treated with these kinase inhibitors. Interestingly, AZ 960 and BX-795, the top two proviral kinase inhibitors in the screen target JAK2 and TBK1/IKKɛ, respectively, both are kinases with major roles in the host's antiviral response.43

To further investigate the efficacies of kinase inhibitors to inhibit influenza H7N9 virus replication, dinaciclib, flavopiridol, and PIK-75 were further evaluated for their dose-dependent activity. These drugs were also evaluated for their potential cytotoxic effects in A549 cells. For cytotoxicity analysis, dinaciclib, flavopiridol, and PIK-75 were titrated directly into the cells from 0.001 to 100 μM in  -log10 increments. Cytotoxic effects were evaluated at 48 h post-treatment by measuring adenylate kinase release into culture supernatants. At the highest inhibitor concentration evaluated, A549 cells exhibit 18.6%, 19%, or 32.3% cytotoxicity for 100 μM dinaciclib, flavopiridol, or PIK-75, respectively. None of the concentration evaluated (up to 100 μM) was substantially cytotoxic, confirming their minimal cytotoxic effects in vitro.

-log10 increments. Cytotoxic effects were evaluated at 48 h post-treatment by measuring adenylate kinase release into culture supernatants. At the highest inhibitor concentration evaluated, A549 cells exhibit 18.6%, 19%, or 32.3% cytotoxicity for 100 μM dinaciclib, flavopiridol, or PIK-75, respectively. None of the concentration evaluated (up to 100 μM) was substantially cytotoxic, confirming their minimal cytotoxic effects in vitro.

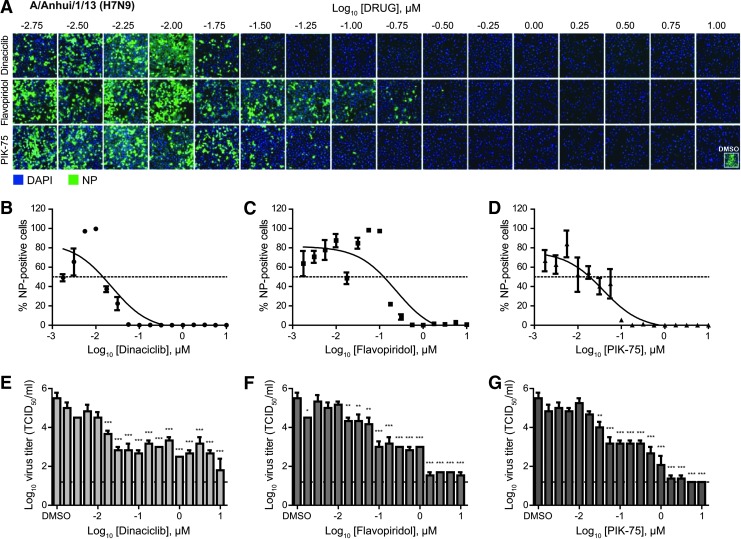

For dose–response antiviral efficacy studies, dinaciclib, flavopiridol, and PIK-75 were titrated from 0.001 to 10 μM in ¼-log10 increments. Validating the findings from the HTS, dinaciclib, flavopiridol, and PIK-75 were found to be highly efficacious against H7N9 with IC50 of 0.02, 0.24, and 0.04 μM, respectively (Fig. 1A–D and Table 1). Virus titration also revealed 4 to 5 log10 reductions of infectious virus in inhibitor-treated compared to DMSO-treated cell supernatants (Fig. 1E–G). The primary screen and validation studies demonstrate the viability of using kinase inhibitors to inhibit H7N9 IAV infection. Supporting this notion, in vitro and in vivo safety data of these inhibitors are readily available, suggesting that these inhibitors can potentially be repurposed as IAV antiviral therapeutic agents.

Fig. 1.

Dose-dependent antiviral efficacy of dinaciclib, flavopiridol, and PIK-75 against influenza H7N9 virus. A549 cells were pretreated with increasing dose (¼-log10 increments) of dinaciclib, flavopiridol, or PIK-75 for 2 h at 37°C. Cells were then infected with influenza A/Anhui/1/13 (H7N9) at MOI of 0.01 in the presence of TPCK-trypsin without removal of inhibitors. At 48 hpi, cells were fixed and stained for viral NP and counterstained with DAPI. (A) Representative immunofluorescence images acquired by Cellomics high-content imaging. (B–D) A percentage of infected cells were quantified using the Cellomics system. IC50 values were determined using the nonlinear regression method in GraphPad Prism and summarized in Table 1. (E–G) Culture supernatants were also collected for virus titration in MDCK cells to determine inhibitors' ability to reduce infectious virus titers. Data are expressed as the mean±SE (n=3). *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001 compared to DMSO-treated cells.

Table 1.

Efficacy of Kinase Inhibitors Against Influenza A H7N9, pdmH1N1, and H3N2 Viruses

| H7N9 | pdmH1N1 | H3N2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor | CC50 (μM)a | IC50 (μM) | SI | IC50 (μM) | SI | IC50 (μM) | SI |

| Dinaciclib | >100 | 0.02 | >4,423 | 0.05 | >2,128 | 0.21 | >484 |

| Flavopiridol | >100 | 0.24 | >425 | 0.59 | >170 | 0.70 | >142 |

| PIK-75 | >100 | 0.04 | >2,627 | 0.32 | >315 | 0.40 | >249 |

aHighest concentration of inhibitors evaluated for cytotoxicity assays was 100 μM. At this concentration, 50% cytotoxicity was still not reached.

Kinase Inhibitors Are Efficacious Against Other IAV Subtypes

To further investigate the broad-spectrum activity of kinase inhibitors against IAV, the efficacy of dinaciclib, flavopiridol, and PIK-75 against two circulating IAV subtypes, H1N1 and H3N2, was evaluated. Similar to the antiviral efficacy assays against the H7N9 virus, these inhibitors were prophylactically tested in A549 cells before infection with a pdmH1N1 strain of influenza virus (A/California/04/09) or a H3N2 influenza strain (A/Philippines/2/82-X79).

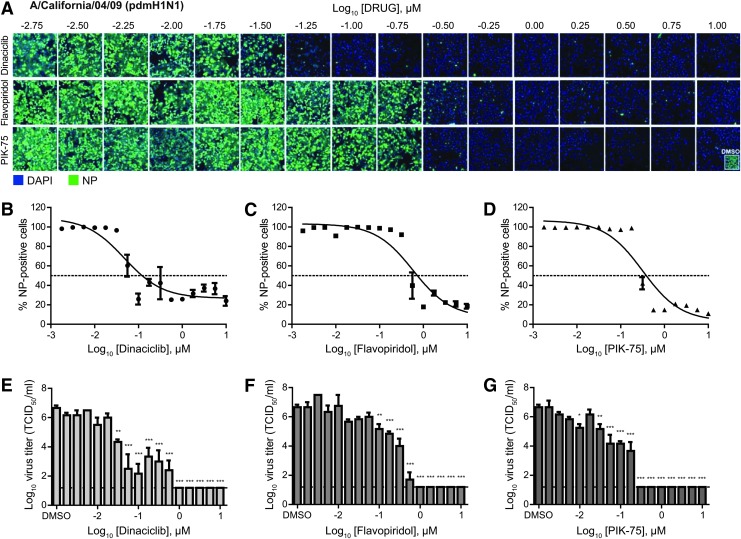

Against these strains, dinaciclib, flavopiridol, and PIK-75 were found to have good efficacies with an SI of greater than 100 (Table 1). Against the pdmH1N1 virus, dinaciclib, flavopiridol, and PIK-75 displayed IC50 of 0.05, 0.59, and 0.32 μM, respectively (Fig. 2A–D and Table 1). Virus titration revealed ∼6 log10 reductions of infectious virus in inhibitor-treated compared to DMSO-treated cell supernatants (Fig. 2E–G). Similarly, against the H3N2 virus, these inhibitors displayed IC50 of 0.21, 0.70, and 0.40 μM for dinaciclib, flavopiridol, and PIK-75, respectively (Fig. 3A–D and Table 1). Virus titration showed 5 to 6 log10 reductions of infectious virus in inhibitor-treated compared to DMSO-treated cell supernatants (Fig. 3E–G). Overall, these findings demonstrated broad antiviral activity of kinase inhibitors dinaciclib, flavopiridol, and PIK-75 against IAV.

Fig. 2.

Dose-dependent antiviral efficacy of dinaciclib, flavopiridol, and PIK-75 against pandemic H1N1 virus. A549 cells were pretreated with an increasing dose (¼-log10 increments) of dinaciclib, flavopiridol, or PIK-75 for 2 h. Cells were then infected with influenza A/California/04/09 (pdmH1N1) at MOI of 0.1 in the presence of TPCK-trypsin without removal of inhibitors. At 48 hpi, cells were fixed and stained for viral NP and counterstained with DAPI. (A) Representative immunofluorescence images acquired by Cellomics high-content imaging. (B–D) A percentage of infected cells were quantified using the Cellomics system. IC50 values were determined using the nonlinear regression method in GraphPad Prism and summarized in Table 1. (E–G) Culture supernatants were also collected for virus titration in MDCK cells to determine inhibitors' ability to reduce infectious virus titers. Data are expressed as the mean±SE (n=3). *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001 compared to DMSO-treated cells.

Fig. 3.

Dose-dependent antiviral efficacy of dinaciclib, flavopiridol, and PIK-75 against an influenza H3N2 virus. A549 cells were pretreated with an increasing dose (¼-log10 increments) of dinaciclib, flavopiridol, or PIK-75 for 2 h. Cells were then infected with influenza A/Philippines/2/82-X79 (H3N2) at MOI of 0.1 in the presence of TPCK-trypsin without removal of inhibitors. At 24 hpi, cells were fixed and stained for viral NP and counterstained with DAPI. (A) Representative immunofluorescence images acquired by Cellomics high-content imaging. (B–D) A percentage of infected cells were quantified with the Cellomics system. IC50 values were determined using the nonlinear regression method in GraphPad Prism and summarized in Table 1. (E–G) Culture supernatants were also collected for virus titration in MDCK cells to determine inhibitors' ability to reduce infectious virus titers. Data are expressed as the mean±SE (n=3). *P<0.05; ***P<0.001 compared to DMSO-treated cells.

Synergistic Antiviral Effects of Kinase Inhibitor Treatment

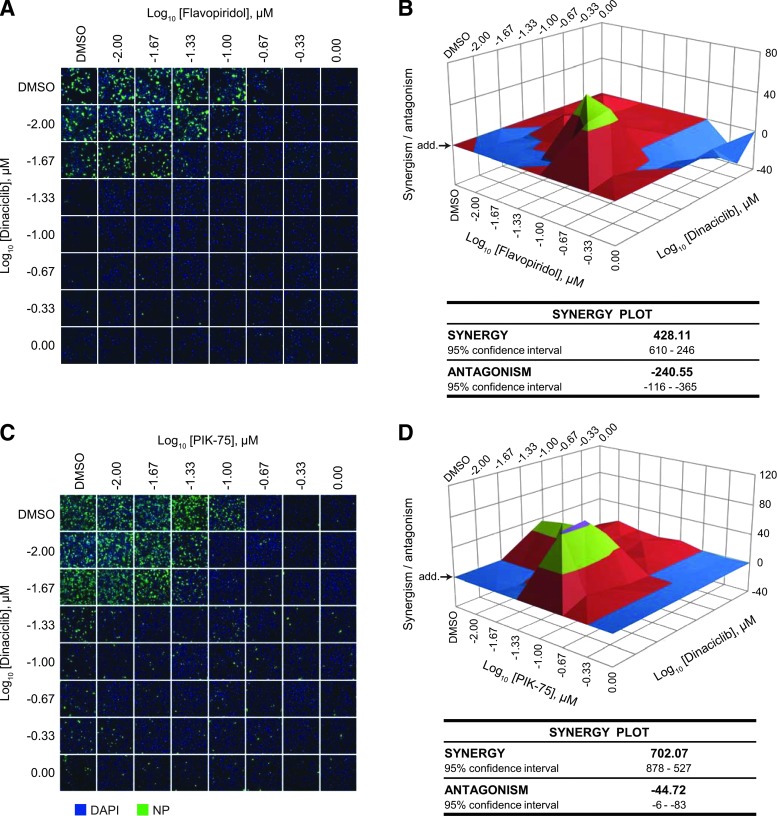

Since dinaciclib and flavopiridol share the same family of targets (the CDK family of kinase), it is expected that these inhibitors act in a synergistic manner against IAV compared to when used alone. To assess this, the HP D300 dispenser was used to titrate the two kinase inhibitors in combination directly into cells from 0.01 to 1 μM. Treated cells were subsequently infected with influenza A/California/04/09 (pdmH1N1) to determine antiviral efficacy. Synergism (or antagonism) value of the inhibitors in combination was computed using the MacSynergyII algorithm, which calculates the deviation from the theoretical additive effect of the inhibitors (depicted as the horizontal plane on the synergism plot) based on their individual dose–response curves. If a higher virus inhibition is observed compared with the theoretical additive effect, then synergism is indicated by above-the-plane spike on the plot, while the antagonism effect is indicated by below-the-plane dip on the plot.

As expected, the inhibitors were synergistic at a low concentration of dinaciclib (0.01 μM) and a moderate concentration of flavopiridol (0.1 μM) (Fig. 4A, B and Supplementary Fig. S2A). Synergy volume was determined to be 428.11 μm2% (95% CI of 610–246 μm2%), although some antagonistic effect was also observed at high inhibitor concentrations. Interestingly, despite targeting different kinases, dinaciclib and PIK-75 were also found to be highly synergistic also at a low dinaciclib concentration (0.01 μM) (Fig. 4C, D, and Supplementary Fig. S2B). Synergy volume was determined to be 702.07 μm2% (95% CI of 878–527 μm2%) with a relatively minimal antagonistic effect.

Fig. 4.

Synergistic antiviral effect of kinase inhibitors. (A, B) A549 cells were treated with flavopiridol alone (A; top row), dinaciclib alone (A; first column), or a combination of the two drugs from 0.01 to 1 μM for 2 h. (C, D) Cells were treated with PIK-75 alone (C; top row), dinaciclib alone (C; first column), or a combination of the two drugs from 0.01 to 1 μM for 2 h. Cells were then infected with influenza A/California/04/09 (pdmH1N1) at MOI of 0.1 in the presence of TPCK-trypsin without removal of drugs. At 48 hpi, cells were fixed and immunostained for viral NP and counterstained with DAPI. (A, C) Representative immunofluorescence images acquired by Cellomics high-content imaging. (B, D) A percentage of infected cells were quantified with the Cellomics system from two independent experiments and the values were used to compute synergism (or antagonism) volume using the MacSynergyII algorithm. Horizontal plane (arrow; add.) represents the theoretical additive effect of the drugs. Above-the-plane volume indicates synergism, while below-the-plane volume indicates antagonism. Synergism and antagonism volumes are summarized.

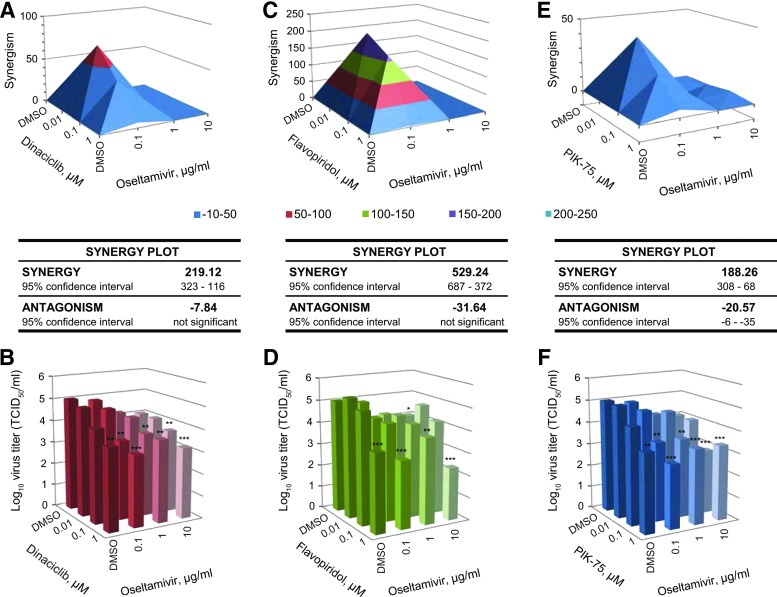

Furthermore, synergism of the kinase inhibitors with an NA inhibitor (NAI) oseltamivir was also assessed. CDK inhibitors dinaciclib and flavopiridol were found to synergize with oseltamivir with a synergy volume of 219.12 (Fig. 5A, B) and 529.24 μm2% (Fig. 5C, D), respectively, with no significant antagonistic effect. PI3K inhibitor PIK-75 was found to be minimally synergistic with oseltamivir with a synergy volume of 188.26 μm2%, although with significant antagonistic effect observed at a higher concentration (Fig. 5E, F). Together, these findings demonstrate that the kinase inhibitors dinaciclib, flavopiridol, and PIK-75 can be used in combination or with currently approved NAIs to achieve optimal virus inhibition, while maintaining low and tolerable dosing when necessary in future in vivo studies.

Fig. 5.

Synergistic antiviral effect of kinase inhibitor with oseltamivir. A549 cells were treated with DMSO or 0.1, 1, or 10 μg/mL of oseltamivir phosphate in combination with DMSO control, dinaciclib (A, B), flavopiridol (C, D), or PIK-75 (E, F) at 0.01, 0.1, or 1 μM for 2 h. Cells were then infected with influenza A/California/04/09 (pdmH1N1) at MOI of 0.1 in the presence of TPCK-trypsin without removal of drugs. At 48 hpi, virus from the supernatant was titered in MDCK cells. Virus titers from three independent experiments were used to compute synergism (or antagonism) volume using the MacSynergyII algorithm. Virus titer results are expressed as the mean (n=3). *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001 compared to DMSO-treated cells.

Kinase Inhibitors Are Active Against Oseltamivir-Resistant Influenza Virus Strain

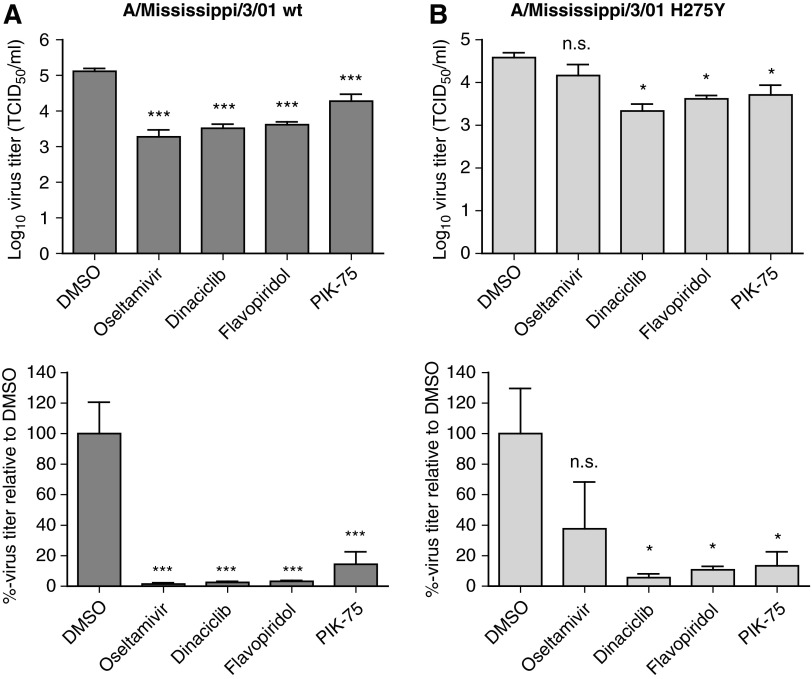

Oseltamivir-resistant seasonal H1N1 influenza A virus has currently spread worldwide and this resistance has been partially attributed to H274Y mutation in the viral NA.44,45 As the option for antiviral therapy is limited for treatment of NAI-resistant influenza strains, efficacy of dinaciclib, flavopiridol, and PIK-75 against an oseltamivir-resistant influenza A/Mississippi/3/01 bearing the H274Y mutation was evaluated. The kinase inhibitors were able to significantly reduce both wild type and H274Y virus titers (Fig. 6). In contrast, the NA inhibitor oseltamivir was only able to reduce replication of the wild-type, but not the H274Y virus. Thus, targeting host kinases by repurposing of the kinase inhibitors dinaciclib, flavopiridol, and PIK-75 can serve as a therapeutic strategy against influenza strains that are resistant to current therapies.

Fig. 6.

Activity of dinaciclib, flavopiridol, and PIK-75 against oseltamivir-resistant virus. A549 cells were treated with DMSO only, oseltamivir phosphate at 10 μg/mL, dinaciclib, flavopiridol, or PIK-75 at 5 μM for 2 h. Cells were then infected with influenza A/Mississippi/3/01 (H1N1) wild type (wt) (A) or H274Y mutant (B) at MOI of 0.1 in the presence of TPCK-trypsin without removal of drugs. At 48 hpi, virus from the supernatant was titered in MDCK cells. Virus titers are expressed as the mean±SE (n=4). *P<0.05; ***P<0.001; n.s. not significant compared to DMSO-treated cells.

Discussion

Annual epidemics caused by influenza average >36,000 deaths and more than 200,000 hospitalizations in the United States alone each year. Furthermore, emerging influenza viruses, such as the highly pathogenic H5N1 virus, and the recent outbreak of H7N9 avian influenza pose looming public health threats. While annual vaccination and a handful of antiviral drugs are currently available, new antivirals against influenza are continually being sought. Drug repurposing may aid timely development of new antiviral drugs against IAV. In the current study, a library containing 273 kinase inhibitors, many are already at advanced stages of clinical evaluations, was screened for their antiviral activity against a newly emerging H7N9 virus with significant pandemic potential. Several kinase inhibitors namely dinaciclib, flavopiridol, and PIK-75 were found to be highly efficacious in nanomolar concentrations against the H7N9 virus, while maintaining good cell viability. These drugs were also found to be efficacious against representative strains from the two circulating IAV subtypes, the pdmH1N1, and H3N2.

Dinaciclib and flavopiridol are known to target various CDKs, while PIK-75 inhibits the cellular PI3K and DNA-PK. Several members of the CDK family have been implicated for their roles during influenza virus replication. For example, CDK9 mediates the activity of influenza virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, and that viral replication was impaired in cells lacking CDK9.46 In addition, a previous study demonstrated flavopiridol activity against influenza A/WSN/33 by inhibiting the host's RNA polymerase II activity, which resulted in reduced viral mRNA transcription.42 Dinaciclib, another CDK inhibitor, which showed up to 12-fold higher efficacy against influenza virus compared to flavopiridol, can also act using a similar mechanism to inhibit influenza virus. Viral mRNA transcription will be evaluated in dinaciclib- and flavopiridol-treated cells infected with various influenza strains in subsequent studies. Other reports also demonstrated the role of CDK and its activating phosphatase CDC25B for the phosphorylation of viral NS1 protein, which is important for antagonism of host antiviral response and efficient virus replication.47,48

While the role of DNA-PK during influenza virus infection is yet understood, the role of PI3K signaling pathway during influenza virus replication has been described in numerous reports. PI3K activation is induced early during influenza virus infection for virus entry and viral ribonucleoprotein export from the nucleus, while it also acts to block premature apoptosis.24,49–51

Dinaciclib blocks the activity of CDK1, 2, 5, and 9, while flavopiridol inhibits CDK 1, 2, 4, and 6, and to some extent EGFR and PKA. It is also important to note that dinaciclib and flavopiridol are currently in various stages of clinical trials as summarized in Table 2, with dinaciclib being the most advanced and is currently investigated in a Phase III trial for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (ClinicalTrials.Gov NCT01580228). PIK-75, which inhibits the activity of PI3K and DNA-PK, is still in a late preclinical evaluation stage for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia, breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, and encephalomyelitis.52–55

Table 2.

Current Clinical Status of Kinase Inhibitors with Anti-Influenza A Activity

Nevertheless, extensive bioactivity and safety data on these drugs have been compiled through preclinical studies and/or clinical trials. Thus, it is expected that these drugs can be developed as novel IAV antiviral drugs in a more expedited time frame once their antiviral efficacies are confirmed in the ensuing in vitro and in vivo studies in animal models of influenza virus infection. Future studies will be aimed to address these inhibitors' molecular mechanism of action against IAV. Furthermore, studies to evaluate their in vivo efficacies against various strains of IAV in animal models of influenza infection, such as mice and ferrets, are also planned. Together, it is expected that these efforts will lead to the development of new antiviral drugs that are efficacious against broad-spectrum IAV strains.

Supplementary Material

Abbrevations Used

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- HA

hemagglutination

- HTS

high-throughput screening

- IAV

influenza A virus

- MOI

multiplicity of infection

- NA

neuraminidase

- NAI

neuraminidase inhibitor

- SI

selectivity indices

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (HHSN266200700006C), and funding from the Georgia Research Alliance. We would like to thank Dr. Weilin Wu and Mrs. Paula Brooks for their scientific input and technical assistance in the HTS, and Mrs. Cheryl Jones for virus propagation assistance.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Fiore AE, Uyeki TM, Broder K, et al. : Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep 2010;59:1–62 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoyert DL, Kung HC, Smith BL: Deaths: preliminary data for 2003. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2005;53:1–48 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Podewils LJ, Liedtke LA, McDonald LC, et al. : A national survey of severe influenza-associated complications among children and adults, 2003–2004. Clin Infect Dis 2005;40:1693–1696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao R, Cao B, Hu Y, et al. : Human infection with a novel avian-origin influenza A (H7N9) virus. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1888–1897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krammer F, Palese P: Universal influenza virus vaccines: need for clinical trials. Nat Immunol 2014;15:3–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palese P: Influenza: old and new threats. Nat Med 2004;10(12 Suppl):S82–S87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McElhaney JE: The unmet need in the elderly: Designing new influenza vaccines for older adults. Vaccine 2005;23(Suppl 1):S10–S25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, et al. : Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the united states. JAMA 2004;292:1333–1340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayden FG, Hay AJ: Emergence and transmission of influenza A viruses resistant to amantadine and rimantadine. Curr Topics Microbiol Immunol 1992;176:119–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiore AE, Fry A, Shay D, Gubareva L, Bresee JS, Uyeki TM: Antiviral agents for the treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza–- recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2011;60:1–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chong CR, Sullivan DJ, Jr.: New uses for old drugs. Nature 2007;448:645–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiMasi JA, Hansen RW, Grabowski HG: The price of innovation: new estimates of drug development costs. J Health Econ 2003;22:151–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DiMasi JA, Hansen RW, Grabowski HG, Lasagna L: Research and development costs for new drugs by therapeutic category. A study of the US pharmaceutical industry. PharmacoEconomics 1995;7:152–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins FS: Mining for therapeutic gold. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2011;10:397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perwitasari O, Bakre A, Tompkins SM, Tripp RA: siRNA genome screening approaches to therapeutic drug repositioning. Pharmaceuticals 2013;6:124–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hao L, Sakurai A, Watanabe T, et al. : Drosophila RNAi screen identifies host genes important for influenza virus replication. Nature 2008;454:890–893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karlas A, Machuy N, Shin Y, et al. : Genome-wide RNAi screen identifies human host factors crucial for influenza virus replication. Nature 2010;463:818–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konig R, Stertz S, Zhou Y, et al. : Human host factors required for influenza virus replication. Nature 2010;463:813–817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meliopoulos VA, Andersen LE, Brooks P, et al. : MicroRNA regulation of human protease genes essential for influenza virus replication. PloS One 2012;7:e37169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meliopoulos VA, Andersen LE, Birrer KF, et al. : Host gene targets for novel influenza therapies elucidated by high-throughput RNA interference screens. FASEB J 2012;26:1372–1386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perwitasari O, Yan X, Johnson S, et al. : Targeting organic anion transporter 3 with probenecid as a novel anti-influenza A virus strategy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013;57:475–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee SM-Y, Yen H-L: Targeting the host or the virus: Current and novel concepts for antiviral approaches against influenza virus infection. Antivir Res 2012;96:391–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar N, Liang Y, Parslow TG, Liang Y: Receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors block multiple steps of influenza A virus replication. J Virol 2011;85:2818–2827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ehrhardt C, Wolff T, Pleschka S, et al. : Influenza A virus NS1 protein activates the PI3K/Akt pathway to mediate antiapoptotic signaling responses. J Virol 2007;81:3058–3067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goubau D, Deddouche S, Reis e Sousa C: Cytosolic sensing of viruses. Immunity 2013;38:855–869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manning G, Whyte DB, Martinez R, Hunter T, Sudarsanam S: The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science (New York, N.Y.). 2002;298:1912–1934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen P: Protein kinases — the major drug targets of the twenty-first century? Nat Rev Drug Discov 2002;1:309–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hopkins AL, Groom CR: The druggable genome. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2002;1:727–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar CC, Madison V: Drugs targeted against protein kinases. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 2001;6:303–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noble MEM, Endicott JA, Johnson LN: Protein kinase inhibitors: insights into drug design from structure. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2004;303:1800–1805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vogel U, Kunerl M, Scholtissek C: Influenza A virus late mRNAs are specifically retained in the nucleus in the presence of a methyltransferase or a protein kinase inhibitor. Virology 1994;198:227–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sasaki Y, Kakisaka M, Chutiwitoonchai N, et al. : Identification of a novel multiple kinase inhibitor with potent antiviral activity against influenza virus by reducing viral polymerase activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2014;450:49–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martinez-Gil L, Alamares-Sapuay JG, Ramana Reddy MV, Goff PH, Premkumar Reddy E, Palese P: A small molecule multi-kinase inhibitor reduces influenza A virus replication by restricting viral RNA synthesis. Antivir Res 2013;100:29–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pleschka S, Wolff T, Ehrhardt C, et al. : Influenza virus propagation is impaired by inhibition of the Raf/MEK/ERK signalling cascade. Nat Cell Biol 2001;3:301–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hirata N, Suizu F, Matsuda-Lennikov M, Edamura T, Bala J, Noguchi M: Inhibition of Akt kinase activity suppresses entry and replication of influenza virus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2014;450:891–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woolcock PR: Avian influenza virus isolation and propagation in chicken eggs. Methods Mol Biol (Clifton, N.J.) 2008;436:35–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reed LJ, Muench H: A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. Am J Epidemiol 1938;27:493–497 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Birmingham A, Selfors LM, Forster T, et al. : Statistical methods for analysis of high-throughput RNA interference screens. Nat Methods 2009;6:569–575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jones RE, Zheng W, McKew JC, Chen CZ: An alternative direct compound dispensing method using the HP D300 digital dispenser. J Lab Autom 2013;18:367–374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szretter KJ, Balish AL, Katz JM: Influenza: Propagation, Quantification, and Storage. Curr Protoc Microbiol 2006: Chapter 15:Unit 15G.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prichard MN, Shipman C, Jr.: Analysis of combinations of antiviral drugs and design of effective multidrug therapies. Antivir Ther 1996;1:9–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang S, Zhang J, Ye X: [Protein kinase inhibitor flavopiridol inhibits the replication of influenza virus in vitro]. Wei Sheng Wu Xue Bao 2012;52:1137–1142 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stewart CE, Randall RE, Adamson CS: Inhibitors of the interferon response enhance virus replication in vitro. PloS One 2014;9:e112014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang MZ, Tai CY, Mendel DB: Mechanism by which mutations at His274 alter sensitivity of influenza A virus N1 neuraminidase to oseltamivir carboxylate and Zanamivir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002;46:3809–3816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Samson M, Pizzorno A, Abed Y, Boivin G: Influenza virus resistance to neuraminidase inhibitors. Antivir Res 2013;98:174–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang J, Li G, Ye X: Cyclin T1/CDK9 interacts with influenza A virus polymerase and facilitates its association with cellular RNA polymerase II. J Virol 2010;84:12619–12627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hale BG, Knebel A, Botting CH, et al. : CDK/ERK-mediated phosphorylation of the human influenza A virus NS1 protein at threonine-215. Virology 2009;383:6–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perwitasari O, Torrecilhas AC, Yan X, et al. : Targeting cell division cycle 25 homolog B to regulate influenza virus replication. J Virol 2013;87:13775–13784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ehrhardt C, Marjuki H, Wolff T, et al. : Bivalent role of the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) during influenza virus infection and host cell defence. Cell Microbiol 2006;8:1336–1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Planz O: Development of cellular signaling pathway inhibitors as new antivirals against influenza. Antivir Res 2013;98:457–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shin Y-K, Liu Q, Tikoo SK, Babiuk LA, Zhou Y: Effect of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway on influenza A virus propagation. J Gener Virol 2007;88:942–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Acosta YY, Montes-Casado M, Aragoneses-Fenoll L, Dianzani U, Portoles P, Rojo JM: Suppression of CD4+T lymphocyte activation in vitro and experimental encephalomyelitis in vivo by the phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase inhibitor PIK-75. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2014;27:53–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Duong HQ, Yi YW, Kang HJ, et al. : Inhibition of NRF2 by PIK-75 augments sensitivity of pancreatic cancer cells to gemcitabine. Int J Oncol 2014;44:959–969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smirnova T, Zhou ZN, Flinn RJ, et al. : Phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling is critical for ErbB3-driven breast cancer cell motility and metastasis. Oncogene 2012;31:706–715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thomas D, Powell JA, Vergez F, et al. : Targeting acute myeloid leukemia by dual inhibition of PI3K signaling and Cdk9-mediated Mcl-1 transcription. Blood 2013;122:738–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fabre C, Gobbi M, Ezzili C, et al. : Clinical study of the novel cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor dinaciclib in combination with rituximab in relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2014;74:1057–1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gojo I, Sadowska M, Walker A, et al. : Clinical and laboratory studies of the novel cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor dinaciclib (SCH 727965) in acute leukemias. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2013;72:897–908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mita MM, Joy AA, Mita A, et al. : Randomized phase II trial of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor dinaciclib (MK-7965) versus capecitabine in patients with advanced breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer 2014;14:169–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nemunaitis JJ, Small KA, Kirschmeier P, et al. : A first-in-human, phase 1, dose-escalation study of dinaciclib, a novel cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, administered weekly in subjects with advanced malignancies. J Transl Med 2013;11:259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ang C, O'Reilly EM, Carvajal RD, et al. : A nonrandomized, phase II study of sequential irinotecan and flavopiridol in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastrointest Cancer Res 2012;5:185–189 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bible KC, Peethambaram PP, Oberg AL, et al. : A phase 2 trial of flavopiridol (Alvocidib) and cisplatin in platin-resistant ovarian and primary peritoneal carcinoma: MC0261. Gynecol Oncol 2012;127:55–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bose P, Perkins EB, Honeycut C, et al. : Phase I trial of the combination of flavopiridol and imatinib mesylate in patients with Bcr-Abl+hematological malignancies. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2012;69:1657–1667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hofmeister CC, Poi M, Bowers MA, et al. : A phase I trial of flavopiridol in relapsed multiple myeloma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2014;73:249–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Karp JE, Garrett-Mayer E, Estey EH, et al. : Randomized phase II study of two schedules of flavopiridol given as timed sequential therapy with cytosine arabinoside and mitoxantrone for adults with newly diagnosed, poor-risk acute myelogenous leukemia. Haematologica 2012;97:1736–1742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Luke JJ, D'Adamo DR, Dickson MA, et al. : The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor flavopiridol potentiates doxorubicin efficacy in advanced sarcomas: preclinical investigations and results of a phase I dose-escalation clinical trial. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:2638–2647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.