Abstract

Malignancies that affect females who survive cancer commonly originate in, invade, and/or metastasize to the sexual organs, including the ovaries, uterine corpus, uterine cervix, vagina, vulva, fallopian tubes, anus, rectum, breast(s), and brain. Females comprise most of the population (in number and proportion) with cancers that directly affect the sexual organs. Most females in the age groups most commonly affected by cancer are sexually active in the year before diagnosis, which includes most menopausal women who have a partner. Among female cancer survivors, the vast majority have cancers that are treated with local or systemic therapies that result in removal, compromise, or destruction of the sexual organs. Additionally, female cancer survivors often experience abrupt or premature onset of menopause, either directly with surgery, radiation, or other treatments or indirectly through disruption of female sex hormone or other neuroendocrine physiology. For many female patients, cancer treatment has short-term and long-lasting effects on other aspects of physical, psychological, and social functioning that can interfere with normal sexual function; these effects include pain, depression, and anxiety; fatigue and sleep disruption; changes in weight and body image; scars, loss of normal skin sensation, and other skin changes; changes in bodily odors; ostomies and loss of normal bowel and bladder function; lymphedema, and strained intimate partnerships and other changes in social roles. In spite of these facts, female patients who are treated for cancer receive insufficient counseling, support, or treatment to preserve or regain sexual function after cancer treatment.

Keywords: cancer, female sexual function, sexual outcome, survivor

Sexuality, which includes sexual activity, sexual function, and sexual and gender identity, is an essential element of life for people with cancer, even those without a current partner.1,2 Sexual drive, function, attractiveness, and satisfying sexual activity are experienced by people with cancer as indicators of and important for overall well-being, vitality, and relationship quality.1 Conversely, loss or lack of sexual drive, impaired sexual function, and sexual activity with pain or without satisfaction can cause individual and relational distress3 and may indicate or cause worry about cancer recurrence or other conditions.4 Impaired sexuality is common among women and men who undergo treatment for cancer5-7 and is highly prevalent among cancer survivors.2,8 Patient education materials for men reliably address issues that are related to sexual function after treatment for prostate cancer.9-12 In contrast to men with cancer, the vast majority of women and girls who are treated for cancer receive no pretreatment information or intervention to preserve or regain sexual function after cancer treatment.13,14

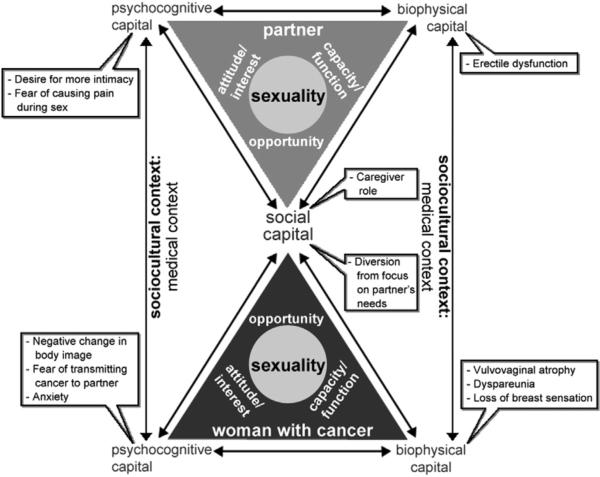

The Interactive Biopsychosocial Model (IBM) is a theoretic framework that was developed by physicians and sociologists for the study of sexuality in the context of aging and illness.15 This model builds on psychiatrist George Engel's16 biopsychosocial model and social capital theory from sociologists Sandefur and Laumann17 (Figure). This model theorizes a bidirectional relationship between health and sexuality across the life course. For example, aromatase inhibitor therapy for breast cancer can cause severe vulvovaginal atrophy that results in secondary dyspareunia.18-20 Conversely, sexual activity with a partner who has human papillomavirus elevates a woman's risk for the development of cervical cancer.21 The IBM proposes a dyadic approach to the study of sexuality that recognizes that most sexual activity occurs with a partner and that each partner's overall health and sexual function contribute to an individual's sexual experience and function. In examples from our clinical practice, a woman with ovarian cancer stops having sex with her husband because she fears she could transmit cancer to him. In another example, a woman with breast cancer complains of painful intercourse that began after her husband experienced erectile difficulties because of prostate cancer treatment. Thorough evaluation of the patient with a sexual concern requires assessment of the physical, psychocognitive, and social dimensions of her and, to the degree possible, her partner's health.

FIGURE. Interactive biopsychosocial model of sexuality.

Interactive Biopsychosocial Model of sexuality in the context of cancer, with examples in each domain that influence sexuality.

Adapted from Lindau et al.15

Lindau. Preserve sexual function in women and girls with cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015.

In the IBM, the term sexuality is used to encompass 3 main attributes of individual sexual expression. Sexual opportunity is defined in the theoretic model as the social possibility for partnership. Women and girls with cancer or cancer history may be disadvantaged in terms of future sexual opportunity. It is not uncommon for a patient to avoid new relationships because of stigma that is related to physical changes like mastectomy, vaginal stenosis, or colostomy or a fear of disclosing infertility or genetic risk that could be passed to offspring.22 Sexual capacity includes sexual activity (types and frequency of partnered or unpartnered physical behaviors such as intercourse, kissing, oral sex, and masturbation) and sexual function. Sexual function includes the physical and physiologic capacity for sex, including desire, arousal, and orgasm as described by the stages of the human sexual response cycle.23,24 Head and neck cancer can interfere with the ability to kiss or engage in oral sex. For a woman who has had a mastectomy to treat breast cancer, the sensation of hugging is altered, and the act of hugging can be painful. Pelvic radiation and/or vulvovaginal surgery for genital cancers can interfere with the capacity for vaginal intercourse and reduce genital sensation and clitoral function.

Sexual attitudes include subjective measures of interest, beliefs, preferences, distress or bother, and satisfaction. Changes in body image, relationship roles, grief, and worry about cancer recurrence can alter sexual attitudes and interfere with sexual satisfaction. The general model hypothesizes that the sociocultural context influences the relationship between sexuality and health. Much of the research underlying this manifesto focuses very specifically on the influence of the medical context (Figure), which includes the effects of patient-physician communication about patient sexual concerns, sexual outcomes after procedures, or side-effects of treatment. Although sexuality is related empirically and meaningfully to overall quality of life and well-being,25,26 the ability to function sexually is also understood as a basic component of human physical function that recognizes that there is individual variation in importance attributed to this aspect of physical function (35% of women and 13% of men 57-85 years old in the United States rate sex as “not at all important”).2

This manifesto calls for gynecologists and other clinicians who provide gynecologic care to preserve sexual function and eliminate unnecessary suffering because of sexual problems in women and girls with cancer. For evidence, we draw on the published, peer-review literature, the clinical and research expertise of the Program in Integrative Sexual Medicine for Women and Girls with Cancer at the University of Chicago,27 and the shared expertise of the international Scientific Network on Female Sexual Health and Cancer.28,29 The term manifesto derives etymologically from the Latin words manifestus, which translated to obvious and, later, manifesto, which meant “to make public” (pg 262).30 The purpose of this clinical opinion is to declare publicly 9 domains of evidence underlying the obvious assertion that ethical and humane care of women and girls who are affected by cancer should optimize the preservation of capacity for sexual function and sexual life. This document was written as a practical tool to be used by clinicians, patient advocates, and others who are motivated to respond to this call to action with an effective argument about the importance of practice change in this domain of women and girls’ health and cancer care.

Manifesto on the preservation of sexual function in women and girls with cancer

Most women and girls with cancer have a cancer that directly affects the sexual organs

Most cancers that affect women who survive cancer originate in, invade, metastasize to, and can be associated with an increased risk for primary cancer that originates in other female sex organs. These cancer types, and the number of women and girls with each type based on 2011 prevalence data from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data, include breast (2,899,726), uterine corpus (610,804), colon and rectum (586,969), uterine cervix (249,632), ovary (188,867), brain (68,715), and anus (26,298).31 Other cancer types, such as, but not limited to, leukemia and lymphoma,32 head and neck cancers,33,34 lung cancer,35 and cancers that affect a woman's partner such as prostate cancer,36 have been shown also to affect female sexual function through physiologic mechanisms.

Women comprise the majority of the population (in number and proportion) that is diagnosed with cancers that directly affect the sex organs.31

The vast majority of women and girls in the age groups that are affected by gynecologic and breast cancers are sexually active in the year before diagnosis, which includes the majority of menopausal women and women in the 6th, 7th, and 8th decades who have a partner.2

Girls and teens have sexual thoughts, engage in masturbation, and develop sexual and gender identity even if menarche and/or puberty are disrupted by cancer or if they were never sexually active with a partner before their cancer diagnosis.37-40

Cancer and cancer treatment can impair female sexuality

Among female cancer survivors, the vast majority have cancers that are treated with local or systemic therapies that result in removal, compromise, or destruction of the sexual organs.41-45 Additionally, female cancer survivors often experience abrupt or premature onset of menopause, either directly because of surgery, radiation, or other treatments or indirectly because of disruption of female sex hormone or other neuroendocrine physiology.46,47

For many women and girls, cancer treatment has short-term and long-lasting effects on other aspects of physical, psychologic, and social functioning that can interfere with normal sexual development and function. These effects include pubertal48 and menstrual disruption49-51; premature menopause46,47; pain, depression, and anxiety52-57; fatigue and sleep disruption49,54-56,58; change in weight and body image49,52-55; scars58; loss of normal skin sensation and other skin changes because of surgery and/or radiation47,50; changes in bodily odors/scents and sounds; ostomies and loss of normal bowel and bladder function53,54; lymphedema59; changes in social roles59; and reliance on medical therapies to treat these conditions.58,60

Women and girls with cancer value their sexuality

The vast majority of women who are diagnosed with cancer value their ability (current or future) to function sexually, to experience sexual feelings, and to be sexually attractive to others. This majority includes women who are older, menopausal, or without a current partner.1

Girls with cancer, especially gynecologic cancer, and/or their caregivers have thoughts, hopes and questions about girls’ sexual development, future fertility,61,62 future sexual function,63 sexual and gender identity,37 and intimate relationships formation.64 These questions commonly go unaddressed in the clinical care of girls with cancer. The American Academy of Pediatrics publishes guidelines, based on age and developmental stage, for talking to children and adolescents about sexuality.65 These guidelines should inform the approach to discussion about sexuality with girls with cancer and their parent(s)/caregiver(s).

Loss of sexual function has negative health consequences for women and girls with cancer and their partners

Women who have or have had cancer and experience loss of current or future sexual function endure physical and psychologic pain and suffering that can erode overall function and quality of life. These effects can extend to a woman's current and future partners.

A woman's ability to function sexually is material to her ability to enter long-lasting life partnerships, marry, and/or enjoy other kinds of sexual and intimate relationships, as well as her ability to sustain these relationships.66

A woman's inability to function sexually can result in relationship strain,8 infidelity (by the patient or her partner), and dissolution or abandonment of marriage or long-lasting life partnerships.67 The consequences of relationship strain also affect the current and future socioeconomic and psychosocial well-being for both the woman with sexual dysfunction and her children.66

A woman of lower socioeconomic status is particularly vulnerable to abuse and/or expulsion from a relationship, home, or family if she is unable to perform sexually.66

Marital and intimate life partnerships are the most important social relationships for an individual's current and future health, especially as one ages. These relationships have been shown to buffer against disease and be associated with better cancer outcomes via biophysiologic mechanisms.68 A woman's spouse or life partner may be called on to make critical end-of-life decisions when a woman is no longer able to do this on her own. In a 2004 US survey of 2750 married couples, 30% of respondents (mean age: wives, 62 years; husbands, 67 years) named their spouse as durable power of attorney for health care.69 In a study of 1083 hospitalized older adults, the spouse was the patient's surrogate decision-maker in 21% of cases.70

On average, middle aged and older couples have sex 2-3 times a month.2 Younger couples have sex once or twice a week.71 Based on data from the general US population, future sexually active life expectancy for a 50-year-old woman is, on average, 15 years.72 Loss of sexual function because of cancer or its treatment can result in hundreds of lost episodes of sexual activity for the patient and her partner.72

Patients want to preserve their sexuality but rarely ask for help

Concerns about loss of sexual function influence patient decision-making about, and adherence to, cancer treatment and cancer risk—reduction recommendations, yet patients rarely voice these concerns.

Women presenting with cancer want their physicians to counsel them about the implications of their cancer, cancer treatment, and cancer risk—reduction therapies for their short- and long-term sexual function because they regard this information as material to coping with, and decision-making about, these treatments, but women and girls with cancer rarely receive this counseling.1,13,73

Women with cancer want to receive care for sexual concerns in the context of considering, receiving, or recovering from cancer diagnosis, treatment, and risk reduction therapies, but rarely receive this care.13,74

When physicians fail to initiate a discussion about sexual outcomes that are related to cancer and its treatment, this signals to patients that sexual outcomes are not relevant, appropriate, or welcome in the context of cancer care and/or that sexual problems in this context are a rare occurrence.46,47

Women who experience, but have not been counseled about, sexual function problems in the context of cancer care commonly believe they are alone, feel ashamed, experience guilt,8 and mistakenly assume that iatrogenic and/or physiologic sexual function problems are “in my head” or because of “not trying hard enough.”

Women who experience, but have not been counseled about, sexual function problems in the context of cancer care often feel hopeless, “broken,” and/or a loss of femininity.8,60,75

Better evidence is needed to optimize sexual outcomes in women and girls with cancer

Ample evidence, which has been accumulated over decades, establishes the prevalence and types of female sexual function problems in the context of a broad range of cancers, but high-quality evidence about incidence, pathophysiologic process, course and effective prevention, and treatment of these problems remains very limited.

This knowledge has been produced and effectively applied to improve outcomes for male populations with cancer, especially prostate cancer,9 at a much more rapid pace than in female populations; attention to the preservation of sexual function and related sexual outcomes is now standard of care for men with prostate cancer.76

Reliable, valid, and efficient tools to assess female sexual function before, during, and after cancer treatment are available and applicable to the general population and to women with cancer.77-83

These tools are slowly being adopted into the care of the general adult female population and in women who have survived cancer but have only scarcely been adopted in the baseline (pretreatment) assessment of women diagnosed newly with, suspected to have, or at increased risk for cancer.84

Women with a new or suspected cancer diagnosis are willing to disclose information about sexual activity and problems, and they exhibit a high prevalence of problems at baseline. In one recent study, 98% of women who were evaluated for initial gynecology oncology assessment answered at least 1 question that pertained to sexual function on a new patient intake form. Of these, 52% indicated at least 1 sexual problem or concern.84

No such tools have been published specifically for use in pediatric or adolescent-age girls in the context of cancer or cancer risk-reduction treatment.

To accelerate discovery in this field, providers across disciplines (especially gynecology, physical therapy, and sex therapy) must harmonize and standardize measures and methods to assess female sexual function, symptoms, and outcomes.

Research is needed to establish effectiveness of treatments for female sexual problems in the context of cancer

Treatments that include patient-provider communication, psychotherapy (eg, sex therapy, couples/marital therapy), physical therapy, nonhormonal and hormonal therapy are being used to address and to a lesser degree prevent, sexual problems in women with cancer.46,74 Recent, thorough reviews of treatments for female sexual dysfunction in the context of cancer have been published.47,85-88

There is very little evidence that these treatments are being applied in or developed for pediatric or adolescent-age girls beyond fertility preservation.

Many of these treatments lack rigorous evidence to establish effectiveness and safety.46,89

Many treatments are applied without specialized training in the area of female function and/or sexual therapy, despite evidence that general training of physicians (which includes gynecologists, oncologists, psychologists and other mental health professionals) includes very little information or transmission of skills in this area.46,50,74

Many women are treated without physical examination to evaluate the female genitalia (including the breasts) by the provider or a collaborating member of the provider's team, despite evidence that sexual function problems in women are often physical or physiologic in origin and accompanied by physical findings.74 Common physical findings that are related to sexual function concerns include the absence or decreased sensation of the breasts, vulvovaginal atrophy, contact dermatitis, and vulvar fissuring, especially at the posterior fourchette. Many women will have a normal physical examination and are reassured by this finding. Physical examination should be a routine element of evaluation of a woman with cancer and sexual function concerns,25,88 following age-based guidelines for appropriate gynecologic examination.25

Reporting an absence of abnormal physical findings and/or educating women about their genital anatomy during physical examination, which includes an assessment with a vaginal dilator,90 can ease fear that is associated with sexual activity and/or alleviate the perception that they have lost physical capacity for sexual activity.91 Recent evidence shows that women and girls tend to underestimate their vaginal capacity after cancer treatment.92

Special effort should be made to include women and girls of sexual minority groups

Special concern and effort, because of established history of stigma and poorer health and cancer outcomes, is warranted to ensure equitable care for lesbian, bisexual, and other women and girls with cancer and sexual function concerns.93 For example, physicians should not assume that lesbian women are not interested in preserving a capacity for vaginal penetration. Even if penetrative sexual intercourse is not desired, vaginal patency is important for future gynecologic examination and, if possible, fertility.

Sexuality is an essential component of female health

Adapted from former Surgeon General David Satcher's 2001 report on sexual health,94 the current and future capacity of a woman or girl with cancer to maintain full agency over her ability to function sexually is essential to her health, quality of life, femininity, and/or personhood, regardless of her age, marital/partner status, sexual identity and orientation, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic or cancer status and includes, but is not limited to, her ability to reproduce.

What can the practicing obstetrician-gynecologist do to elevate the quality of care and preserve sexual outcomes for women and girls with cancer?

Routinely elicit patient sexual function

Improved care for a woman's sexual concerns after cancer can happen only if the patient's concerns are elicited. Include this simple, validated, routine screening item to assess sexual function at least on an annual basis: “Do you have any sexual problems or concerns?”95 Inclusion of this brief item will signal to your patient that sexual function is within bounds of obstetrics/gynecology care, will normalize sexual function concerns (“my doctor didn't ask, so I assumed I was the only one with this problem...”) and will convey that you regard her as a complete human being. In a study of new patients being evaluated for gynecologic oncology care, 52% indicated that they had a problem, but the problem was recognized and addressed only for 14%.84 Eliciting a patient's concern only works if the physician reviews and acts on her response.

Provide anticipatory guidance

If a patient indicates no sexual function concerns, say “You indicate that your sexual function is good. It's not uncommon to experience some changes in sexual function during or after cancer treatment and with age. Let me know if anything comes up.”

Normalize the patient's concerns and arrange a time to focus specifically on them

If a patient indicates sexual function concerns, say “I see you have some difficulty with your sexual function. As many as 40-50% of women report changes or problems with sexual function during or after cancer. These problems are usually manageable and should improve over time.” If you have time (it can take 30 minutes for a therapeutic discussion), ask if she can tell you more about what she's experiencing. If you don't have time, ask if she would be willing to come back for a focused meeting just about her sexual concerns. Invite her to bring her partner.

Provide resources

Offer your patient resources (Table 1) with which she can obtain products or services you recommend to preserve or improve her sexual function (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Patient and provider resources for addressing sexual concerns related to cancer

| Resource | Description |

|---|---|

| For patients | |

| American Association of Sex Educators, Counselors and Therapists (AASECT) | A resource list of certified sex therapists by specialty and geographic location; available at: aasect.org |

| American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) | A resource list of women's health certified pelvic physical therapists and education about pelvic physical therapy; available at: apta.org |

| The International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health (ISSWSH) | A resource list of sexual health fellows practicing in the field; available at: isswsh.org |

| The Scientific Network on Female Sexual Health and Cancer (The Network) | A resource list compiled and curated by an interdisciplinary group of international experts on cancer and female sexuality; available at: cancersexnetwork.org |

| The Society for Sex Therapy and Research (SSTAR) | A therapist directory that allows patients to search for certified sex therapists in their area; available at: sstar.org |

| For providers | |

| Institute for Sexual Medicine (Irwin Goldstein MD President and Director) | Provides training for professionals in basic science research and clinical care in the field of sexual medicine; available at: theinstituteforsexualmedicine.com |

| The International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health (ISSWSH) | Offers a special interest group and provider trainings focused on female sexual health and cancer |

| The Scientific Network on Female Sexual Health and Cancer (The Network) | Offers membership to professionals with an interest in evidence-based approaches to the prevention and management of female sexual problems in the context of cancer |

| The Society for Sex Therapy and Research (SSTAR) | Offers member benefits that include access to resources in the field and continuing education credits at SSTAR meetings |

| University of Chicago's Program in Integrative Sexual Medicine (Stacy Tessler Lindau MD MAPP Director) | Offers on-site consultation education and clinical site visits for professionals who seek to create a regional clinical and research program including a multisite research registry; available at: www.uchospitals.edu/specialties/obgyn/prism.html (contact slindau@uchicago.edu) |

Lindau. Preserve sexual function in women and girls with cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015.

TABLE 2.

Patient resources for obtaining products or services to address sexual concerns or problems

| Concern | Product or service | Resources |

|---|---|---|

| Individual or couple distress related to sexual concerns | Psychotherapy, sex therapy, couples or marital therapy, mindfulness therapy, group support | See www.aasect.org or www.sstar.org to find trained, local therapists; community-based cancer support or wellness centers; the Cancer Support Community's Cancer Support Helpline (888-793-9355; available at: www.cancersupportcommunity.org) |

| Pelvic floor dysfunction, including urinary and fecal incontinence | Pelvic physical therapy | American Physical Therapy Association website to find a local, specialized women's health physical therapist: available at: http://www.womenshealthapta.org/pt-locator |

| Vaginal dryness | Lubricants, moisturizers | Purchase over-the-counter at a drug store or online equivalent or grocery store for food-grade products (eg, oils) |

| Vaginal stenosis or vaginismus | Vaginal dilators, vibrators, or dildos | Obtaining medical-grade vaginal dilators requires a physician prescription; other products can be purchased over-the-counter at drug stores, pharmacies, sexual product stores, or online equivalentsa |

| Male sexual dysfunction | Medical evaluation and treatment | Most urology practices offer treatment for male sexual dysfunction; www.urologyhealth.org provides patient-focused tools to locate a local urologist from among American Urological Association members |

Information on vaginal dilators can be found online by the use of a combination of the following search terms: medical grade, silicone, vaginal dilator, and vaginismus.

Lindau. Preserve sexual function in women and girls with cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015.

Develop expertise to fill this need for care in your community

Enroll in a course or specialized training (Table 1) to learn more about the treatment and prevention of sexual problems in women with cancer. Promote your skills to providers who are involved in the care of women and girls with cancer (eg, adult and pediatric oncologists, reconstructive surgeons, psychologists, general obstetrician gynecologists, internists, family physicians, physical therapists, nurses). Join the Scientific Network on Female Sexual Health and Cancer at www.cancersexnetwork.org. Create educational materials (website, brochures, posters) that communicate openness to all women and girls (we include the Rainbow Flag symbol) regardless of sexual identity or orientation and age.

Call to action

For the evidence-based reasons stipulated here, this manifesto asserts that all women and girls of all ages who are affected by cancer, especially with cancer or cancer treatment that directly affects the female sex organs (including, but not limited to, the breasts), be provided with evidence-based care to optimize preservation of current and future capacity for sexual function and sexual life. This manifesto further stipulates that the treatment of women and girls with cancer risk—reducing strategies should include an evidence-based approach to prevention and management of sexual problems or dysfunction that might result from surgical or chemopreventive or other strategies to reduce future risk of cancer.

Women and girls with cancer and the people who love them should be informed fully about the putative and known effects of cancer and cancer treatments on their capacity for future sexual function and life. Gynecologists, gynecologic oncologists, and other providers who render gynecologic care are particularly well-positioned to set the standard for the ethical and humane treatment of all women and girls with cancer, which includes the preservation of female sexual function. The slow pace of change from the medical profession in the adoption of practices that help women and girls with cancer preserve their sexual function is likely, at least in part, due to limited options for effective treatment of female sexual problems. The voices of patient advocates must be heard to motivate medical practice change and the pace of development of effective therapies. Obstetrician gynecologists and patient advocates who wish to effect change beyond their own practice or experience can use the evidence-based arguments outlined in this manifesto to inform and activate policymakers, advocacy groups, and health care professionals about this important gap in care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We acknowledge Ms Isabella Joslin, Research Assistant in the Lindau Laboratory at the University of Chicago, for her substantive contribution to this article through extensive review and synthesis of the literature and for logistical and research support.

Supported by a career development award from the National Institute on Aging (1K23AG032870-01A1; S.T.L., PI), the Chicago Core on Biomeasures in Population-Based Health and Aging Research (CCBAR) at the NORC-University of Chicago Center on Demography and Economics of Aging under its gerosexuality special emphasis area (5 P30 AG 012857; L. Waite, PI), and a philanthropic gift from Ms Ellen Block to the University of Chicago Program in Integrative Sexual Medicine for Women and Girls with Cancer.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest.

S.L. reports that she is founding chair and immediate past chair of the Scientific Network on Female Sexual Health and Cancer, an organization operated from the University of Chicago until 12/31//14 and now from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, both not-for-profit organizations. She receives no compensation for these roles.

The opinions expressed in this article are the authors’ own and do not reflect the view of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the United States government.

Presented in part as “Cancer and Female Sexuality: Moving from Observation to Evidence-Based Care” at the Society for Sex Therapists and Researchers 37th Annual Scientific Meeting, Chicago, IL, March 29-31, 2012 and as “A Call to Action to Preserve Sexual Function in Women and Girls with Cancer” at the Oncofertility Consortium Virtual Grand Rounds, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, April 12, 2012.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lindau S, Gavrilova N, Anderson D. Sexual morbidity in very long term survivors of vaginal and cervical cancer: a comparison to national norms. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;106:413–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindau S, Schumm L, Laumann E, Levinson W, O'Muircheartaigh C, Waite L. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:762–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laumann E, Paik A, Rosen R. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA. 1999;281:537–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen BL, Lachenbruch PA, Anderson B, deProsse C. Sexual dysfunction and signs of gynecologic cancer. Cancer. 1986;57:1880–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860501)57:9<1880::aid-cncr2820570930>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aerts L, Enzlin P, Verhaeghe J, Poppe W, Vergote I, Amant F. Long-term sexual functioning in women after surgical treatment of cervical cancer stages IA to IB: a prospective controlled study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24:1527–34. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersen BL. Sexual functioning complications in women with gynecologic cancer: outcomes and directions for prevention. Cancer. 1987;60(suppl 8):2123–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19901015)60:8+<2123::aid-cncr2820601526>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schover L, Baum G, Fuson L, Brewster A, Melhem-Bertrandt A. Sexual problems during the first 2 years of adjuvant treatment with aromatase inhibitors. J Sex Med. 2014;11:3102–11. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juraskova I, Butow P, Robertson R, Sharpe L, McLeod C, Hacker N. Post-treatment sexual adjustment following cervical and endometrial cancer: a qualitative insight. Psychooncology. 2003;12:267–79. doi: 10.1002/pon.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alemozaffar M, Regan MM, Cooperberg MR, et al. Prediction of erectile function following treatment for prostate cancer. JAMA. 2011;306:1205–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung E, Brock G. Sexual rehabilitation and cancer survivorship: a state of art review of current literature and management strategies in male sexual dysfunction among prostate cancer survivors. J Sex Med. 2013;10(suppl 1):102–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.03005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Cancer Institute [Nov. 7, 2014];Prostate cancer treatment (PDQ) 2014 Available at: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/prostate/Patient/page4.

- 12.Martin NE, Massey L, Stowell C, et al. Defining a standard set of patient-centered outcomes for men with localized prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2015;67:460–7. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.08.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hill E, Sandbo S, Abramsohn E, et al. Assessing gynecologic and breast cancer survivors’ sexual health care needs. Cancer. 2011;117:2643–51. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park E, Bober S, Campbell E, Recklitis C, Kutner J, Diller L. General internist communication about sexual function with cancer survivors. J Gen Int Med. 2009;24(suppl 2):S407–11. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1026-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindau ST, Laumann EO, Levinson W, Waite LJ. Synthesis of scientific disciplines in pursuit of health: the interactive biopsychosocial model. Perspect Biol Med. 2003;46(suppl 3):S74–86. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2003.0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129–36. doi: 10.1126/science.847460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sandefur RL, Laumann EO. A paradigm for social capital. Rationality and Society. 1998;10:481–501. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baumgart J, Nilsson K, Evers AS, Kallak TK, Poromaa IS. Sexual dysfunction in women on adjuvant endocrine therapy after breast cancer. Menopause. 2013;20:162–8. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31826560da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baumgart J, Nilsson K, Stavreus-Evers A, et al. Urogenital disorders in women with adjuvant endocrine therapy after early breast cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:26.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kallak TK, Baumgart J, Goransson E, Nilsson K, Poromaa IS, Stavreus-Evers A. Aromatase inhibitors affect vaginal proliferation and steroid hormone receptors. Menopause. 2014;21:383–90. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e31829e41df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Feb. 10, 2014];What are the risk factors for cervical cancer? 2014 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/cervical/basic_info/risk_factors.htm.

- 22.Kurowecki D, Fergus KD. Wearing my heart on my chest: dating, new relationships, and the reconfiguration of self-esteem after breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2014;23:52–64. doi: 10.1002/pon.3370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaplan H. Disorders of sexual desire and other new concepts and techniques in sex therapy. Simon and Schuster; New York: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masters W, Johnson V. Human sexual response. Vol. 1. Little, Brown & Co; Boston: 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 25.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice Well-woman visit. Committee Opinion, no.: 534 (2012) 2014;120:421–4. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182680517. Reaffirmed: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rohde G, Berg KH, Haugeberg G. Perceived effects of health status on sexual activity in women and men older than 50 years. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:43. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-12-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.University of Chicago Medicine [Nov. 7, 2014];Program in integrative sexual medicine for women and girls with cancer. 2014 Available at: http://www.uchospitals.edu/specialties/obgyn/prism.html.

- 28.Scientific Network on Female Sexual Health and Cancer [Nov. 7, 2014];Website homepage. 2014 Available at: http://cancersexnetwork.org/.

- 29.Goldfarb SB, Abramsohn E, Andersen BL, et al. A national network to advance the field of cancer and female sexuality. J Sex Med. 2013;10:319–25. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cuthbert A. Understanding cities: method in urban design. Routledge; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Cancer Institute [Nov. 7, 2014];Surveillance, epidemiology and end results (SEER) program. 2011 doi: 10.1002/cncr.29049. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2011/browse_csr.php. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Greaves P, Sarker SJ, Chowdhury K, et al. Fertility and sexual function in long-term survivors of haematological malignancy: using patient-reported outcome measures to assess a neglected area of need in the late effects clinic. Br J Haematol. 2014;164:526–35. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Low C, Fullarton M, Parkinson E, et al. Issues of intimacy and sexual dysfunction following major head and neck cancer treatment. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:898–903. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moreno KF, Khabbaz E, Gaitonde K, Meinzen-Derr J, Wilson KM, Patil YJ. Sexuality after treatment of head and neck cancer: findings based on modification of sexual adjustment questionnaire. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:1526–31. doi: 10.1002/lary.23347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reese JB, Shelby RA, Abernethy AP. Sexual concerns in lung cancer patients: an examination of predictors and moderating effects of age and gender. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:161–5. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-1000-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eisemann N, Waldmann A, Rohde V, Katalinic A. Quality of life in partners of patients with localised prostate cancer. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:1557–68. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0588-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Evan E, Kaufman M, Cook A, Zeltzer L. Sexual health and self-esteem in adolescents and young adults with cancer. Cancer Supplement. 2006;107:1672–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fritz GK, Williams JR. Issues of adolescent development for survivors of childhood cancer. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1988;27:712–5. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198811000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance: United States, 2013. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2014;63(suppl 4):1–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klosky JL, Howell CR, Li Z, et al. Risky health behavior among adolescents in the childhood cancer survivor study cohort. J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37:634–46. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jss046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) for Breast Cancer V.3.2014. National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc; 2014. [Nov. 7, 2014]. All rights reserved. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) for Cervical Cancer V.2.2015. National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc; 2014. [Nov. 7, 2014]. All rights reserved. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) for Colon Cancer V.2.2015. National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc; 2014. [Nov. 7, 2014]. All rights reserved. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) for Rectal Cancer V.1.2015. National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc; 2014. [November 7, 2014]. All rights reserved. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) for Uterine Neoplasms V.1.2015. National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc; 2014. [Nov. 7, 2014]. All rights reserved. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bober SL, Varela VS. Sexuality in adult cancer survivors: challenges and intervention. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3712–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.7915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Falk SJ, Dizon DS. Sexual dysfunction in women with cancer. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:916–21. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brougham MF, Kelnar CJ, Wallace WH. The late endocrine effects of childhood cancer treatment. Pediatr Rehabil. 2002;5:191–201. doi: 10.1080/1363849021000039407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fobair P, Stewart SL, Chang S, D'Onofrio C, Banks PJ, Bloom JR. Body image and sexual problems in young women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15:579–94. doi: 10.1002/pon.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krychman M, Millheiser LS. Sexual health issues in women with cancer. J Sex Med. 2013;10(suppl 1):5–15. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosenberg SM, Tamimi RM, Gelber S, et al. Treatment-related amenorrhea and sexual functioning in young breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2014;120:2264–71. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Begovic-Juhant A, Chmielewski A, Iwuagwu S, Chapman LA. Impact of body image on depression and quality of life among women with breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2012;30:446–60. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2012.684856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Burns M, Costello J, Ryan-Woolley B, Davidson S. Assessing the impact of late treatment effects in cervical cancer: an exploratory study of women's sexuality. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2007;16:364–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carter J, Chi DS, Abu-Rustum N, Brown CL, McCreath W, Barakat RR. Brief report: total pelvic exenteration: a retrospective clinical needs assessment. Psychooncology. 2004;13:125–31. doi: 10.1002/pon.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cull A, Cowie VJ, Farquharson DI, Livingstone JR, Smart GE, Elton RA. Early stage cervical cancer: psychosocial and sexual outcomes of treatment. Br J Cancer. 1993;68:1216–20. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1993.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ferrell B, Smith SL, Cullinane CA, Melancon C. Psychological well being and quality of life in ovarian cancer survivors. Cancer. 2003;98:1061–71. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Green MS, Naumann RW, Elliot M, Hall JB, Higgins RV, Grigsby JH. Sexual dysfunction following vulvectomy. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;77:73–7. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Flynn KE, Jeffery DD, Keefe FJ, et al. Sexual functioning along the cancer continuum: focus group results from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS(R)). Psychooncology. 2011;20:378–86. doi: 10.1002/pon.1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Janda M, Obermair A, Cella D, Crandon AJ, Trimmel M. Vulvar cancer patients’ quality of life: a qualitative assessment. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2004;14:875–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1048-891X.2004.14524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bergmark K, Avall-Lundqvist E, Dickman PW, Henningsohn L, Steineck G. Vaginal changes and sexuality in women with a history of cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1383–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905063401802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zebrack B, Bleyer A, Albritton K, Medearis S, Tang J. Assessing the health care-needs of adolescents and young adult cancer patients and survivors. Cancer. 2006;107:2915–23. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zebrack BJ, Casillas J, Nohr L, Adams H, Zeltzer LK. Fertility issues for young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology. 2004;13:689–99. doi: 10.1002/pon.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bellizzi KM, Smith A, Schmidt S, et al. Positive and negative psychosocial impact of being diagnosed with cancer as an adolescent or young adult. Cancer. 2012;118:5155–62. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stam H, Grootenhuis MA, Last BF. The course of life of survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology. 2005;14:227–38. doi: 10.1002/pon.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Braverman PK, Breech L, American Academy of Pediatrics Clinical report: gynecologic examination for adolescents in the pediatric of-fice setting. Pediatrics. 2010;126:583–90. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Daly M, Wilson M. The evolutionary psychology of marriage and divorce. In: Waite L, Bachrach C, editors. The ties that bind: perspectives on marriage and cohabitation. Aldine de Gruyter; New York: 2000. pp. 91–110. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ratner ES, Foran KA, Schwartz PE, Minkin MJ. Sexuality and intimacy after gynecological cancer. Maturitas. 2010;66:23–6. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Waite L, Das A. Families, social life, and well-being at older ages. Demography. 2010;47(suppl):S87–109. doi: 10.1353/dem.2010.0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Moorman SM, Hauser RM, Carr D. Do older adults know their spouses’ end-of-life treatment preferences? Res Aging. 2009;31:463–91. doi: 10.1177/0164027509333683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Torke AM, Sachs GA, Helft PR, et al. Scope and outcomes of surrogate decision making among hospitalized older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:370–7. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Eisenberg ML, Shindel AW, Smith JF, Breyer BN, Lipshultz LI. Socioeconomic, anthropomorphic, and demographic predictors of adult sexual activity in the United States: data from the National Survey of Family Growth. J Sex Med. 2010;7:50–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01522.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lindau ST, Gavrilova N. Sex, health, and years of sexually active life gained due to good health: evidence from two US population based cross sectional surveys of ageing. BMJ. 2010;340:c810. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sobecki J, Curlin F, Rasinski K, Lindau S. What we don't talk about when we don't talk about sex: results of a national survey of U.S. obstetrician/gynecologists. J Sex Med. 2012;9:1285–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02702.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Berman L, Berman J, Felder S, et al. Seeking help for sexual function complaints: What gynecologists need to know about the female patient's experience. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:572–6. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04695-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stead ML, Fallowfield L, Selby P, Brown JM. Psychosexual function and impact of gynaecological cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;21:309–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) for Prostate Cancer V.1.2015. National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc; 2014. [Nov. 7, 2014]. All rights reserved. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Baser RE, Li Y, Carter J. Psychometric validation of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) in cancer survivors. Cancer. 2012;118:4606–18. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Derogatis LR. The Derogatis Interview for Sexual Functioning (DISF/DISF-SR): an introductory report. J Sex Marital Ther. 1997;23:291–304. doi: 10.1080/00926239708403933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Derogatis LR, Rosen R, Leiblum S, Burnett A, Heiman J. The Female Sexual Distress Scale (FSDS): initial validation of a standardized scale for assessment of sexually related personal distress in women. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28:317–30. doi: 10.1080/00926230290001448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Flynn KE, Lin L, Cyranowski JM, et al. Development of the NIH PROMIS (R) Sexual Function and Satisfaction measures in patients with cancer. J Sex Med. 2013;10(suppl 1):43–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02995.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Quirk F, Haughie S, Symonds T. The use of the sexual function questionnaire as a screening tool for women with sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2005;2:469–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Taylor JF, Rosen RC, Leiblum SR. Self-report assessment of female sexual function: Psychometric evaluation of the Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for Women. Arch Sex Behav. 1994;23:627–43. doi: 10.1007/BF01541816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kennedy V, Abramsohn E, Makelarski J, et al. Can you ask? We just did! Assessing sexual function and concerns in patients presenting for initial gynecologic oncology consultation. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137:119–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.01.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Banner L. Sex therapy in female sexual dysfunction. In: Mulhall J, Incrocci L, Goldstein I, Rosen R, editors. Cancer and sexual health. Springer; New York: 2011. pp. 649–56. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Burrows L, Goldstein A. Surgical treatments for sexual problems in women. In: Mulhall J, Incrocci L, Goldstein I, Rosen R, editors. Cancer and sexual health. Springer; New York: 2011. pp. 643–7. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Graziottin A, Serafini A. Medical treatments for sexual problems in women. In: Mulhall J, Incrocci L, Goldstein I, Rosen R, editors. Cancer and sexual health. Springer; New York: 2011. pp. 627–41. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Krychman M, Dizon DS, Amsterdam A, Kellogg Spadt S. Evaluation of the female with sexual dysfunction. In: Mulhall J, Incrocci L, Goldstein I, Rosen R, editors. Cancer and Sexual Health. Springer; New York: 2011. pp. 351–6. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jordan R, Hallam TJ, Molinoff P, Spana C. Developing treatments for female sexual dysfunction. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:137–41. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Robinson JW, Faris PD, Scott CB. Psychoeducational group increases vaginal dilation for younger women and reduces sexual fears for women of all ages with gynecological carcinoma treated with radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;44:497–506. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lindau S, Abramsohn E, Makelarski J, Yamada S. Perceived versus actual vaginal capacity in women with sexual function concerns. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2011;15(supplement 1):S27. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kennedy V, Abramsohn E, Asiedu L, et al. Perceived versus measured functional vaginal capacity in women with sexual function concerns [abstract 9528]. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl) [Google Scholar]

- 93.Diamant AL, Schuster MA, Lever J. Receipt of preventive health care services by lesbians. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19:141–8. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Office of the Surgeon General . The Surgeon General's call to action to promote sexual health and responsible sexual behavior. US Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville, MD: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Flynn KE, Lindau ST, Lin L, et al. Development and validation of a single-item screener for self-reporting sexual problems in US adults. J Gen Int Med. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3333-3. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]