Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Interpersonal violence, which includes child abuse and neglect, youth violence, intimate partner violence, sexual violence, and elder abuse, affects millions of US residents each year. However, surveillance systems, programs, and policies to address violence often lack broad, cross-sector collaboration, and there is limited awareness of effective strategies to prevent violence.

OBJECTIVES

To describe the burden of interpersonal violence in the United States, explore challenges to violence prevention efforts and to identify prevention opportunities.

DATA SOURCES

We reviewed data from health and law enforcement surveillance systems including the National Vital Statistics System, the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Uniform Crime Reports, the US Justice Department’s National Crime Victimization Survey, the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence, the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System, the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System, and the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System—All Injury Program.

RESULTS

Homicide rates have decreased from a peak of 10.7 per 100 000 persons in 1980 to 5.1 per 100 000 in 2013. Aggravated assault rates have decreased from a peak of 442 per 100 000 in 1992 to 242 per 100 000 in 2012. Nevertheless, annually, there are more than 16 000 homicides and 1.6 million nonfatal assault injuries requiring treatment in emergency departments. More than 12 million adults experience intimate partner violence annually and more than 10 million children younger than 18 years experience some form of maltreatment from a caregiver, ranging from neglect to sexual abuse, but only a small percentage of these violent incidents are reported to law enforcement, health care clinicians, or child protective agencies. Moreover, exposure to violence increases vulnerability to a broad range of mental and physical health problems over the life course; for example, meta-analyses indicate that exposure to physical abuse in childhood is associated with a 54% increased odds of depressive disorder, a 78% increased odds of sexually transmitted illness or risky sexual behavior, and a 32% increased odds of obesity. Rates of violence vary by age, geographic location, sex, and race/ethnicity, and significant disparities exist. Homicide is the leading cause of death for non-Hispanic blacks from age 1 through 44 years, whereas it is the fifth most common cause of death among non-Hispanic whites in this age range. Additionally, efforts to understand, prevent, and respond to interpersonal violence have often neglected the degree to which many forms of violence are interconnected at the individual level, across relationships and communities, and even intergenerationally. The most effective violence prevention strategies include parent and family-focused programs, early childhood education, school-based programs, therapeutic or counseling interventions, and public policy. For example, a systematic review of early childhood home visitation programs found a 38.9% reduction in episodes of child maltreatment in intervention participants compared with control participants.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

Progress has been made in reducing US rates of interpersonal violence even though a significant burden remains. Multiple strategies exist to improve violence prevention efforts, and health care providers are an important part of this solution.

Interpersonal violence is a pervasive public health, social, and developmental threat. It is a leading cause of death in the United States, particularly among children, adolescents, and young adults. Exposure to violence can cause immediate physical wounds that clinicians recognize and treat but can also result in long-lasting mental and physical health conditions that are often less apparent to health care providers. Violence directly affects health care expenditures. Indirectly, it stunts economic development, increases inequality, and erodes human capital.

Interpersonal violence is defined by the World Health Organization as the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against another person or against a group or community that results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation.1 Although violence has a long history of study by various fields, a focus on public health approaches to prevention has largely emerged over the past 3 decades. In 1992, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) established the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control as the focal point for advancing a public health approach to violence prevention in the United States.

The Burden of Violence

Status and Progress Made

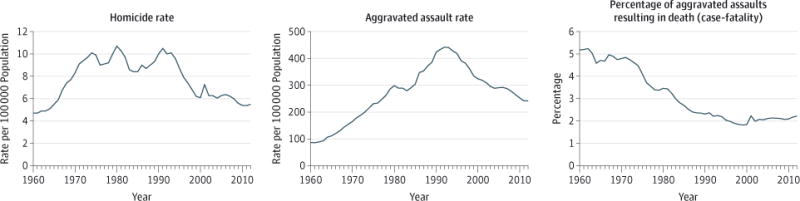

Homicide rates have varied over the past 50 years. Beginning in the 1960s, the homicide rate in the United States increased steadily from about 4 to 5 deaths per 100 000 persons to a peak of 10.7 deaths per 100 000 in 1980.2 Homicide rates remained markedly elevated through the mid-1990s and raised the profile of violent crime in political and social discourse. Rates of aggravated assault were 86 per 100 000 in 1960, peaked at 442 per 100 000 in 1992, and decreased to 242 per 100 000 in 2012 (Figure).

Figure. Homicide, Assault, and Case-fatality Rates, United States, 1960–2012.

The homicide rate is from the National Center for Health Statistics3 and the assault rate is from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).4 The case-fatality rate (or lethality rate) was conceptualized by Harris et al5 and is calculated herein as the homicide rate divided by the homicide rate plus the assault rate (multiplied by 100 to display percentage). An aggravated assault is defined by the FBI as an unlawful attack by one person on another for the purpose of inflicting severe or aggravated bodily injury, usually accompanied by the use of a weapon or by means likely to produce death or great bodily harm.

The increase in homicides from the late 1960s to the 1990s (Figure and Table 1) has been attributed to factors such as the elevated proportion of youth among the population resulting from the post–World War II baby boom; the spread of multiple drugs of abuse; the proliferation of more powerful firearms; and rapid changes in family structures, cultural norms, and societal dynamics.6 Since the early 1990s, homicide rates have declined, but they still exceed rates in other high-income countries. The World Health Organization’s Global Status Report on Violence Prevention places the 2012 US homicide rate at 5.4 per 100 000, whereas the rate for Canada was 1.8; for the United Kingdom, 1.5; and for Australia, 1.1 per 100 000.7

Table 1.

Status and Progress Made on Fatal and Nonfatal Violence, United States

| Type of Violence | Rate or % | Data Source, Data Type | Year | Summary and Progress |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatal | ||||

| Homicide rate, per 100 000 population | 5.1 | NVSS, administrative (death certificates) | 2013 | Homicide rates have decreased from peak of 10.7 per 100 000 population in 1980; current rate equals 1964 rate2 From 2004 to 2013, homicide rates decreased 23% in large central metropolitan counties, 10% in suburbs, and were unchanged in rural areas8 |

| Nonfatal | ||||

| Aggravated assault rate, per 100 000 population | 242 | UCR, administrative (law enforcement) | 2012 | Rates have decreased 45% from a peak of 442 per 100 000 population in 19924 |

| Violence among high school students, % | ||||

| In physical fight in preceding year | 24.7 | YRBS, health survey | 2013 | In 1991, 42.5% of high-school students reported being in a physical fight in the preceding year9 |

| Carried a weapon | 17.9 | YRBS, health survey | 2013 | In 1991, 26.1% of high-school students reported carrying a knife, gun, or club in preceding 30 d9 |

| Child maltreatment, % | ||||

| Experience maltreatment by age 18 y that is reported to and confirmed by child protective service agenciesa | 12.5 | NCANDS, 2011 administrative (child protective services reports)10 | 2011 | From 1992 to 2012, substantiated sexual abuse declined by 62%; physical abuse by 54%, and neglect by 14%11 Research on 1997–2009 hospitalization rates have detected no change in injury from child abuse among young children12 and a 4.9% increase in severe physical maltreatment among children <18 y13 |

| Aged 14–17 y who have experienced maltreatment in their life (reported and unreported)b | 41.2 | NatSCEV, health survey | 2011 | Long-term data not available |

| Partner violence in lifetime, % | ||||

| Rapec | Women, 8.8, Men, 0.5 |

NISVS, health survey | 2011 | Long-term NISVS data not available. National 1994–2011 crime survey data indicates the rate of intimate partner violence against females (including rape/sexual assault, robbery, and aggravated assault by a current or former spouse, boyfriend, or girlfriend) decreased from 5.9 episodes per 1000 persons to 1.6 per 1000, a 72% decrease.14 |

| Physical violence | Women, 31.5 Men, 27.5 |

NISVS, health survey | 2011 | |

| Dating violence among high school students, % | ||||

| Physical or sexual violence during the past year among students who dated | Girls, 20.9 Boys, 10.4 |

YRBS, health survey | 2013 | Long-term trend data on this specific measure not available |

| Sexual violence, % | ||||

| Raped by any perpetratorc | Women, 19.3 Men, 1.7 |

NISVS, health survey | 2011 | Long-term NISVS data not available. 1995–2010 NCVS data indicates rates of rape or sexual assault among women declined 58% from 5.0 episodes per 1000 population to 2.1 per 1000, although rates have plateaued since 200515 |

| Unwanted, nonpenetrative sexual contact in their lifetime | Women, 27.3 Men, 10.8 |

NISVS, health survey | 2011 | |

| Elder abuse, % | ||||

| Community-dwelling adults ≥60 y who experienced emotional abuse, potential neglect, physical abuse, or sexual abuse over past year | 11.4 | National health research survey16 | 2008 | Long-term data not yet available |

Abbreviations: NatSCEV, National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence; NCANDS, National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System; NCVS, National Crime Victimization Survey; NISVS, National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey; NVSS, National Vital Statistics System; YRBS, Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System; UCR, Uniform Crime Reports.

Definitions of child maltreatment in NCANDS data can vary slightly from state to state but generally include neglect, physical abuse, psychological maltreatment, and sexual abuse.

Child maltreatment in NatSCEV defined as physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, neglect, or custodial interference/family abduction.

Rape defined as completed or attempted forced penetration, or alcohol or drug-facilitated penetration.

For many forms of nonfatal violence—including child maltreatment, youth violence, intimate partner violence, sexual violence, and elder abuse—progress has also been made, but the burden remains high (Table 1). For example, from 1992 to 2012, official reports by child protective service agencies of substantiated sexual abuse declined by 62%, physical abuse by 54%, and neglect by 14%; however, an estimated 12.5% of US children still experience confirmed child maltreatment by age 18 years.10,11 Furthermore, a recent analysis of national crime survey data indicates that from 1995 to 2010, rates of rape or sexual assault among females decreased 58% from 5.0 episodes to 2.1 episodes per 1000 population; however, nearly 1 in 5 women (19.3%) have experienced rape (completed or attempted unwanted penetration) at some point in their life and experience the sequelae of such violence.15,17

The tables and figure in this report synthesize information from multiple, national violence data systems maintained by the CDC, the US Department of Justice, the US Administration for Children and Families, and other partners, including the National Vital Statistics System, the Uniform Crime Reports, the National Crime Victimization Survey, the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence, the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System, the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System, and the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System–All Injury Program. These data sources are diverse and range from household surveys to official administrative data (see eTable 1 in the Supplement for a description of the major data systems used).

The Hiddenness of Violence

Nearly all homicides are reported to health and safety officials and are counted in public data sources, but nonlethal violence is often unreported (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). For example, in 2011, approximately 1570 children younger than 18 years died from child maltreatment.18 In that year more than 3 million children received an investigation or response from state child protective services departments,18 but it is estimated that most episodes of child maltreatment were not reported. National survey data from 2011 estimate that 13.8% of children (calculated to be >10 million youth), had experienced some form of maltreatment by a caregiver.19 Child maltreatment can go undetected for a considerable amount of time; clinicians must be vigilant to avoid missed opportunities for detection and referral by recognizing symptoms and signs of maltreatment in clinical encounters.20

Violence toward adults is also underreported. Survey data from the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey estimate that more than 12 million women and men report experiencing some form of violence (rape, physical violence, or stalking) by an intimate partner each year, but only approximately 480 000 injuries are reported to police annually and 150 000 injuries receive medical treatment (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). The US Justice Department surveillance systems indicate that other forms of violent crime are underreported as well (eFigure 3 in the Supplement).

One reason that violence is underrecognized is that violence reporting systems are compartmentalized; the CDC’s National Violent Death Reporting System synthesizes information from several sources of data, but it only covers deaths and is currently operational in only 32 states. Medical, public health, police, judicial, child welfare, educational, correctional, and community agencies and organizations have also not yet built mechanisms for comprehensive, coordinated responses to violence.

Risk Factors for Perpetration of Multiple Types of Violence

Many forms of violence are interconnected at the individual level, across relationships and communities, and even intergenerationally. Traditionally, efforts to understand, prevent, and respond to interpersonal violence have been constrained by the way violence has been categorized—usually in terms of the relationship between the perpetrator and the survivor (eg, parent or caregiver-child, peer to peer, partner or spouse), but different categories of violence have similar risk factors or protective factors. A survivor of violence may also be a violence perpetrator.21 Individuals experience multiple forms of violence and some perpetrators may perpetrate multiple types of violence.22 A family may experience both child maltreatment as well as partner violence,23 and perpetrators of family violence may also be violent toward nonfamily members.24 Exposure to violence as a child (either directly or as a witness) is a strong and consistent predictor of future violence exposure as an adolescent or adult as well as the perpetration of violence as an adolescent or adult.25,26

Table 2 shows select risk factors that may influence the perpetration of multiple forms of violence at different levels of the social ecology—individual, family, community, and society. With regard to individual-level risk factors for violence, there are certain neuropsychological deficits, such as hostile attributional biases and poor impulse control, that can be present among perpetrators of different forms of violence.27–29 For example, poor impulse control can involve problems with excessive anger or hyperreactivity to a given stimulus, such as a child crying.27 In meta-analyses, poor impulse control is associated with a 0.34 correlation with physical child abuse perpetration and a 0.15 correlation with youth violence perpetration.27,28 These types of processing deficits may result from exposure to chronic stressors prenatally or in early childhood affecting the volume, connectivity, and chemistry of the brain. Though these changes do not directly lead to violence perpetration, they can leave an individual impaired in many areas of functioning, which can contribute to violence involvement. For example, with hostile attributional biases, individuals may incorrectly perceive an offense to themselves where none was intended—such as a youth who interprets a glance from peers or a collision in the hallway with another student to be a threat, where no insult was actually intended (correlation coefficient for youth violence of 0.13).

Table 2.

Select Individual, Family, Community, and Society-Level Factors Associated With the Perpetration of Multiple Forms of Interpersonal Violencea

| Factors or Conditions | Child Maltreatmentb | Youth Violence (Including Bullying)b | Partner Violence (Teen and Adult)b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation Coefficient | P Value | Correlation Coefficient | P Value | Correlation Coefficient | P Value | |

| Individual | ||||||

| Hostile attributional biases | 0.3027c | <.001 | 0.1328d | <.05 | +29 | |

| Poor impulse control | 0.3427c | <.001 | 0.1528d | <.001 | +29 | |

| Alcohol or drug abuse | 0.1727c | <.001 | 0.3028d | +29 | ||

| Experienced abuse as a child | 0.2127c | <.001 | 0.0728d | <.05 | +29 | |

| Family | ||||||

| Poor parent-child relationship | 0.2227c | <.001 | 0.1528d | <.05 | +29 | |

| Familial economic stress/socioeconomic status | 0.1427c | <.001 | 0.2428d | +29 | ||

| Family conflict | 0.3927c | <.001 | 0.1228d | <.05 | +29 | |

| Community | ||||||

| Disadvantaged neighborhood | +30 | +31 | +32 | |||

| Poor neighborhood cohesion or organization | +30 | +31 | +32 | |||

| Exposure to neighborhood violence | +30 | +33 | +32 | |||

| Society | ||||||

| Income inequality | 0.1734e | <.001 | 0.4435 | <.01 | 0.0436e,f | <.05 |

| High prevalence of poverty | 0.2534e | <.001 | 0.4435 | <.01 | 0.0637e | <.01 |

This table details select risk factors for violence perpetration and effect size expressed as a correlation coefficient, where available. The individual-level factor or condition refers to that of the perpetrator of violence. Correlation coefficients are unadjusted measures that indicate the strength of the relationship between 2 variables but do not indicate causality and may occasionally act as proxies for other constructs. The variance explained by any 1 risk factor is generally small; this list of risk factors should not be considered all inclusive. Nearly all measures in this Table are drawn from systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Exceptions are indicated.

For systematic reviews that do not report correlation coefficients, + denotes articles reporting that more than 50% of studies reviewed indicate a positive association with violence perpetration.

Correlations are for child physical abuse.

Based on longitudinal studies; predictors at ages 6 through 11 years of offending at ages 15 through 25 years.

Effect measure from a single study.

Corresponds to an ordered logit model regression coefficient.

There are many causes of stressors to children that can affect brain development or are associated with violence perpetration later in life, including child maltreatment and witnessing partner violence. Chronic stressors may result from living conditions that affect children directly, such as poverty. At the societal level, high levels of income inequality have been linked to multiple forms of violence. A study of income inequality across 3142 US counties detected a 0.17 correlation between county-level income inequality and official child maltreatment reports; cross-national studies have also found significant associations between income inequality and other forms of violence.34–36 Additionally, stressors can occur indirectly by means of their effects on parental well-being and parenting behaviors. Structural disadvantage and racism can also contribute to the perpetration of multiple forms of violence.38 Although most of the risk factors listed in Table 2 are associated with chronic stress in the lives of children, it is important to note that the variance explained by any 1 risk factor is generally small. Consequently, although these risk factors should be considered in exploring opportunities for prevention, intervening solely on 1 risk factor may have limited effect. Research suggests that it is the accumulation of multiple adverse experiences that is associated with the greatest risk of subsequent likelihood of violence involvement. In contrast to the effect of risk factors, adverse health outcomes may be buffered by protective factors, such as safe, stable, and nurturing family relationships and high levels of support and cohesion within communities.31

Challenges for Violence Prevention

Disparity

Rates of violence vary by age group, geographic location, sex, race, and ethnicity. For example, homicide is the leading cause of death for non-Hispanic blacks from age 1 through 44 years, whereas it is the fifth most common cause of death among non-Hispanic whites in this age range. This high rate among African Americans is primarily driven by exceptionally high rates among males between the ages of 15 and 34 years.3 Child protective services reports from 2013 indicate that the rate of child maltreatment is 8.1 per 1000 children among white, 14.6 among black, and 8.5 among Hispanic children.18 Differences in child maltreatment rates as well as other forms of violence are attributable to underlying risk factors, such as poverty.39 Table 3 displays disparities in violence by race/ethnicity; disparities in rates of violence increase with the severity of violence (ie, homicide vs nonfatal violence).

Table 3.

Rates of Experiencing Violence by Race and Ethnicitya

| Type of Violence | (Non-Hispanic) | Non-Hispanic | Black:White Non-Hispanic Ratiob | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | White | Black | Hispanic | American Indian/Alaska Native | Asian/Pacific Islander | ||

| Homicides per 100 000 populationc | 2013 | 2.5 | 18.7 | 4.5 | 8.4 | 1.6 | 7.5 |

| Aggravated assaults per 1000 population | 2013 | 3.4 | 6.0 | 3.7 | 1.8 | ||

| Women reporting experiencing rape in their life, %d | 2011 | 20.5 | 21.2 | 13.6 | 27.5 | 1.0 | |

| Women reporting experiencing physical violence by an intimate partner in their life, % | 2011 | 30.5 | 41.2 | 29.7 | 51.7 | 15.3 | 1.4 |

| Annual child maltreatment cases per 1000 childrene | 2013 | 8.1 | 14.6 | 8.5 | 12.5 | 1.7/7.9 | 1.8 |

| High school students in physical fight in past year, % | 2013 | 20.9 | 34.7 | 28.4 | 1.7 | ||

Data sources: homicide data from National Vital Statistics System; assault data from National Crime Victimization Survey; rape and intimate partner violence data from the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey; child maltreatment data from the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System; fight data from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System.

The ratio is calculated by dividing the non-Hispanic black figure by the non-Hispanic white figure; this column is shown to highlight the magnitude of the disparity between fatal and nonfatal violence by race.

Rates of homicide are age adjusted.

Rape is defined as completed or attempted forced penetration, or alcohol or drug-facilitated penetration. An intimate partner can include current or former spouses (including married spouses, common-law spouses, civil union spouses, and domestic partners), boyfriends or girlfriends, dating partners, and ongoing sexual partners.

Child maltreatment is defined as determination that maltreatment was substantiated or indicated; or the child was considered an alternative response victim. Rates of child maltreatment are reported separately for Asian and Pacific Islander.

Violence disproportionately affects younger individuals—rates of experiencing homicide among those between the ages of 15 and 39 years are more than 2-fold higher than those among individuals 40 years or older.3 The increase in homicide rates from 1985 to 1993 was largely accounted for by an increase in homicide among individuals aged 15 to 24 years.40 Rates of violence also vary by location; for example, metropolitan areas have greater homicide rates than suburban or rural areas.8 Variation in rates of violence by geographic area may be attributable to social constructs such as inequality and poor social cohesion, which are elevated in urban areas.41

Slowing Decrease in Case-Fatality Rates

The proportion of assaults resulting in the death of an individual (ie, the case-fatality rate) has declined markedly since the 1960s (Figure). This decline in the lethality of assaults is believed to be largely attributable to improvements in the quality and availability of trauma care. Over the past several decades, the number of hospitals, hospital capacity, physician availability and specialization, and technology used in caring for individuals who are critically ill has improved and such measures have been associated with lethality reductions on the county level.5 Injured patients receiving care at trauma centers have a lower risk of death than those treated at other facilities.42 However, since the mid-1990s, decreases in case-fatality rates have slowed (Figure). It appears that there is a limit to which skilled critical care can save patients’ lives; clinicians and health care systems should consider ways to become more involved in violence prevention.

Health Consequences of Violence

Beyond physical injuries, which are the most apparent consequences of violence, the association between violence and infectious diseases, especially sexually transmitted infections (STIs) such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), is well established.43,44 For example, although forced sexual intercourse can directly transmit infectious agents, sexual and nonsexual violence are also associated with subsequent early sexual debut, multiple partners, failure to use condoms or other forms of protection, and other behaviors that increase the risk of STIs. In a recent meta-analysis, relative to children experiencing no abuse, the odds of contracting STIs or engaging in risky sexual behaviors ranged from 57% higher among those children experiencing neglect to 78% higher among children experiencing physical abuse.44 Beyond the risk of STIs, exposure to abuse as a youth is also associated with adverse reproductive health outcomes, including fetal death and postpartum depression.45

Experiencing violence (physical, sexual, psychological) is associated with increased risks of mental health and behavioral disorders such as depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, personality and conduct disorders, anxiety, sleep and eating disorders, substance abuse, and suicide and suicide attempts.46 For example, meta-analyses indicate that children who were physically abused have a 54% increased odds of depressive disorders and a 92% increased odds of drug use.44 Children experiencing emotional abuse or neglect can have even higher rates of psychological comorbidities (>300% increased odds of depressive disorders from emotional abuse and >200% increased odds from neglect, relative to children without abuse exposure).44 Psychosocial outcomes in adulthood associated with past experiences of childhood violence may also include problems with finances, family, jobs, anger, and stress.45

Lastly, violence is also associated with the development of major noncommunicable diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, chronic lung disease, and diabetes as well as key risk factors for several chronic diseases, including harmful alcohol use, tobacco use, physical inactivity, and obesity.44,47 For example, data from meta-analyses, indicate that children who have experienced physical abuse have a 55% increased odds of tobacco smoking and a 32% increased odds of obesity, relative to nonabused children.44 Although the relationship between childhood violence exposure and many noncommunicable diseases is still emerging, a growing number of prospective, longitudinal studies are establishing strong associations.

Opportunities for Prevention

Violence prevention programs are often developed to address certain forms of violence (eg, child maltreatment, partner violence, youth violence) rather than multiple forms of violence. By focusing on those strategies that can reduce multiple forms of violence, practitioners have the potential to maximize gains in violence prevention. In Table 4 and Table 5, we highlight violence prevention strategies with some evidence for an effect on multiple forms of violence and that have been evaluated by major violence prevention evaluation bodies or possess other strong experimental evidence. The oldest and most tested violence prevention strategies are largely parent- and family-focused programs, early childhood education, therapeutic or counseling interventions, school-based programs, and public policy approaches.

Table 4.

Examples of Violence Prevention Strategies That Can Impact Multiple Forms of Violencea

| Approach | Example Program/Intervention | Descriptionb | Level of Evidence | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Washington State Institute for Public Policy (Benefit Minus Cost From Meta-analysis48), $c | Blueprints for Healthy Youth Developmentd | Systematic Review Intervention Recommendations49e | |||

| Early childhood visitation | Nurse-Family Partnership | Nurses visit low-income families during pregnancy, after birth, and first few years of life; Support women for improved health, pregnancy outcomes, child care, social support, educational attainment, and employability |

17 332 | Model program | Task Force: early childhood home visitation to prevent child maltreatment |

| Parenting training | Parent Management Training, Oregon Model | Group and individual parent training sessions delivered in a range of settings and focused on communication, child development, parent-child bonding, parenting skills, behavior management techniques | NA | Model program | Cochrane review: supports behavioral and cognitive behavioral group–based parenting for child conduct problems (includes Oregon Model)50 Campbell review: supports early family/parent training to prevent antisocial behavior and delinquency51 |

| School-based social-emotional learning approaches | Life Skills Training | Typically delivered to school-aged students; includes problem-solving skills, emotional regulation, and resistance skills Involves didactic instruction, demonstrations, practice-based learning, and strategies for multiple risk behaviors |

1028 | Model program | Task Force review: universal school-based programs Campbell review: school-based bullying prevention programs52 |

| Early childhood education | Child-Parent Centers/Head Start | Multiple models of early childhood education and support ranging from universal prekindergarten to additional health, social, or parental support | 26 386 (pre-kindergarten) 16 068 (Head Start)f |

NA | NA |

| Public policy | Increasing alcohol prices | Increasing alcohol prices by 10% is associated with a 5.0% decrease in beer, 6.4% in wine, and 7.9% in spirit consumption Other policy approaches include restricting outlet density |

NA | NA | Task Force review: increasing alcohol prices to reduce excessive consumption and related harms (includes studies on violence) |

| Therapeutic approaches | CBT | Addresses distorted thought patterns and beliefs that can lead to harmful actions; targeting thought patterns aims to improve management of behaviors and emotions; can be used to reduce trauma-related harms and problem or criminal behaviors | 10 777 (adult) 6738 (child)g |

NAh | Task Force review: individual and group CBT for reducing psychological harm from traumatic events (including physical and sexual abuse, exposure to school, community, and domestic violence) Campbell review: demonstrated a 25% reduction in crime recidivism53 |

Abbreviations: CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; NA, not evaluated.

Strategies selected have evidence for affecting more than 1 form of violence as determined from leading violence prevention program evaluation bodies; thus, some programs that target 1 form of violence are not discussed. Example programs are those reviewed by the evaluation bodies listed. The list is not all inclusive and inclusion should not necessarily be viewed as an endorsement over comparable programs.

Program descriptions are abbreviated.

Benefit-cost provided is for listed example program unless otherwise noted. Formulae available in reference technical documentation. Benefit-cost calculations account for multiple outcomes and expenses.

Programs designed as ‘Model’ are based on level of randomized clinical trial evidence and other criteria. Model programs require a minimum of (1) 2 high-quality randomized control trials or (2) 1 high-quality randomized control trial plus 1 high-quality quasi-experimental evaluation. Programs must also demonstrate sustained effect for 12 or more months after the intervention and be ready for dissemination. See www.blueprintsprograms.com for full criteria.

The Community Preventive Services Task Force is an independent, nonfederal, unpaid panel of public health and prevention experts.

For prekindergarten programs funded by states or local school districts; Head Start is federally funded.

For adult moderate- to high-risk offenders; benefit for juvenile offenders not yet available; $6738 for child trauma.

Program refers to a general approach.

Table 5.

Promising Interventionsa

| Approach | Example Program/Intervention | Description | Evidence for Effectiveness (Evidence Described as Programs Not Yet Evaluated by Listed Evaluation Bodies) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brief clinical interventions | SEEK | Primary care–based approach to identify targeted risk factors, brief interventions such as motivational interviewing, handouts, and resource referrals, including social worker support | RCTs suggest that SEEK is associated with reduced child maltreatment and may also reduce intimate partner violence54,55 |

| Bystander training | Green Dot | Educate and empower individuals witnessing violence or harmful behaviors to act and shift social norms | A systematic review of campus sexual assault prevention showed some behavioral change56A systematic review of bullying prevention programs was associated with increased bystander intervention57 |

| Income supports | WIC, Food Stamp Program, or other supplements | Supplement family income: programs can provide foodstuffs; other services; or direct cash transfers, subsidies, or tax credits | Income supplement programs have been evaluated in randomized and quasi-experimental longitudinal designs: the Minnesota Family Investment Program, an alternative welfare structure that provided increased financial incentives for families, was administered through random allocation and was associated with decreased domestic violence and child behavioral problems58 Another rigorous evaluation among Native American families demonstrated that income supplements from the opening a casino was associated with a decrease in conduct disorders among children who moved out of poverty59 |

| Built environment modifications | Green space creation or provision | Access to green space by cleaning vacant lots and planting grass or trees or through housing assignments | Random assignment of urban public housing residents to areas of increased green space was associated with decreased levels of partner violence60 and a longitudinal, decade-long, difference-in-differences analysis demonstrated that vacant lot greening was associated with decreased gun assaults61 |

Abbreviations: NA, not evaluated; RCTs, randomized clinical trials; SEEK, Safe Environment for Every Kid; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Other promising interventions are those not yet reviewed by the evaluation bodies listed but with experimental evidence suggesting potential effect on multiple forms of violence.

Parent- and family-focused programs provide education and training to parents with the goal of improving emotional bonds between parents and children and teaching participants how to effectively discipline, monitor, and supervise children as well as strengthen access to social support and other resources. Programs for young children with components that teach parents communication skills and positive parent-child interaction skills and that include active role play and practice produce greater preventive effects than those without these components.62 Although parenting and family focused programs can vary substantially in content, method, and setting, a systematic review of early childhood home visitation programs detected a 38.9% reduction in episodes of child maltreatment in intervention participants compared with control participants.63 The earlier parenting and family programs are delivered in a child’s life, the greater the benefits; however, significant benefits have also been demonstrated when delivered to adolescent populations.64

The evidence also suggests that early childhood education can prevent future violence involvement. Early childhood education programs are associated with positive social and emotional development, lower rates of official reports of child abuse and neglect, less aggression and child behavior problems, and higher rates of secondary school completion and have also demonstrated long-term effects on violent and criminal behavior.65,66 One example is the Chicago Child-Parent Center program, which provides a comprehensive educational program beginning in preschool, as well as other family support services to economically and educationally disadvantaged children.67 A 15-year follow-up of preschool program participants across 25 sites in Chicago demonstrated statistically significant lower rates of juvenile arrests in the intervention vs control group (16.9% vs 25.1%, respectively).67

There is also substantial evidence for therapeutic approaches and universal school-based violence prevention programs. Not only do therapeutic programs reduce the trauma-related harms of experiencing violence, but they also can prevent subsequent violence involvement. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and Multi-systemic therapy are 2 examples of therapeutic approaches. A Campbell Collaboration meta-analysis of CBT programs for criminal offenders demonstrated a crime recidivism reduction of 25% (recidivism rate of 0.30 in the intervention group compared with 0.40 in the control group over approximately 12 months after the intervention period).53 As for universal school-based programs, such approaches are associated with a 15% relative reduction in violent behavior in students across all school years participating in these programs and a 29% reduction in violence among students in high school.68 School-based programs have demonstrated reductions in both peer violence and teen dating violence and are also cost-effective.48,69

Although many policy-level interventions for violence remain to be tested, there is some evidence for policies that aim to reduce alcohol-related harms. Given the strong association between alcohol use and violence involvement, reductions in alcohol consumption are expected to be associated with reduced levels of multiple forms of violence. Based on systematic reviews, the Community Preventive Services Task Force recommends increasing alcohol prices, limiting days and hours of sale, regulation of alcohol outlet density, upholding liability of establishments for alcohol-related harm committed by customers (dram shop liability), enhanced enforcement of laws prohibiting the sale of alcohol to minors, and screening and brief interventions for problem drinkers.49

There are also other policy- and community-level approaches that represent promising strategies to prevent multiple forms of violence. Violence is higher in communities where there are limited economic opportunities; where there are high concentrations of poor and unemployed people; where people move frequently; and where there are limited public, mental health, and social services available to residents and fewer civic and voluntary associations.31 Consequently, the evidence for other policy- and community-level approaches to address these characteristics points to income-strengthening approaches (eg, subsidies or cash transfers), urban upgrading (eg, improved transportation, lighting, buildings, green space), economic development strategies (eg, business improvement districts), and residential mobility programs that enable families living in disadvantaged environments to resettle in more advantaged neighborhoods.70–72 Increasing family income through subsidies or cash transfers, for example, has been shown to reduce child abuse and neglect, youth violence, and partner violence.58,59,71

Lastly, bystander strategies are increasingly being used to prevent sexual violence, teen-dating violence, and bullying. With this approach, participants are trained to recognize potentially violent situations or behaviors that they see occurring and are taught skills to safely intervene. This approach also seeks to change underlying social norms that promote violence. A meta-analysis of bystander education to prevent sexual assault on college campuses found moderate effects on both bystander efficacy and intentions to help others at risk; smaller but significant effects were seen on increasing actual bystander helping behaviors, decreasing acceptance of rape myths, and decreasing rape proclivity.56 Additionally, a recent meta-analysis of bullying programs detected an increase in bystander interventions among program recipients (an increase of 20% of 1standard deviation more than control group participants).57

Although less is known about the modifiable factors that serve as protective buffers in the face of disadvantage, previous research suggests that connectedness and community-level collective efficacy are protective factors that may offset many of the negative influences in disadvantaged environments. These factors also seem to be protective across multiple forms of violence, including child maltreatment, youth violence, intimate partner violence, and suicidal behavior.73 Although, to date, few interventions in these areas have been tested and evaluated, it is a promising area for future research. It is also important to acknowledge the significant contributions to violence prevention and response elucidated by other domains, such as criminology. Strategies such as problem-oriented policing are also associated with important effects on violence reduction. The science of violence prevention has made significant progress over the last 2 decades. Widespread dissemination and adoption of available evidence-based strategies, however, is still needed.

Role of Health Care Systems and Clinicians

Many health care or clinical approaches to violence prevention are still early in development and, in general, there is limited experimental evidence for such approaches. However, a variety of strategies are being pursued and merit additional evaluation. Individuals exposed to violence can use health care services at a high rate and some clinicians have established programs designed to prevent their patients’ future involvement in violence and recidivism for violent injury (Box).76,80 Such programs often are operated by emergency departments and trauma services80,81; however, primary care clinics also have implemented programs to prevent violence, such as the Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) model, a pediatric outpatient program. The SEEK program consists of identification of risk factors, offering brief counseling, and referring patients for services. A randomized clinical trial in which participants were followed up for more than 3.5 years found that children whose families were in the SEEK intervention had a significantly lower rate of official child protective services reports of child maltreatment (13.3%) than did those in the control group (19.2%). Intervention families also experienced improved health benefits such as lower rates of delayed immunizations.54 In addition to the identification of risk factors for violence involvement, clinicians can be trained to recognize the signs and symptoms that may be associated with experiencing violence, such as injuries; unexplained chronic pain; gastrointestinal symptoms; genitourinary symptoms; repeated unintended pregnancies or sexually transmitted disease; symptoms of depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders; alcohol or other substance abuse82; and behavioral problems in children.

Box. Action Steps for Health Care Systems and Clinicians.

Identify

Clinical trials in pediatric primary care settings suggest that identification of violence-associated risk factors, brief interventions, and referrals may reduce some forms of violence54,55

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends that clinicians screen women of childbearing age for intimate partner violence. Through appropriate training, clinicians can also improve their identification of women experiencing abuse even if they cannot screen all asymptomatic patients.74 Electronic medical records can prompt physicians on appropriate language and response if a patient screens positive

With the Affordable Care Act insurers can no longer deny coverage to individuals by using domestic violence and related sequelae as a preexisting condition, more of these patients may be entering routine medical care75

Intervene

Create, expand, and evaluate emergency department, trauma, or other clinical programs that work with those patients presenting with injury; some such programs have been linked with subsequent decreased emergency department utilization or violent behavior76

Use mental health interventions, particularly those designed to reduce trauma and other violence-related harms77

Collaborate

Develop new community collaborations. For example, hospital and police department partnerships have led to promising interventions for violence prevention78

Consider participating in and offering services as a part of coordinated centers, such as Family Justice Centers (the co-location of multiple agencies to facilitate patients receiving comprehensive, wrap-around services such as legal, medical, housing/shelter, child care, advocacy)

Train

Provide training in trauma-focused care to all staff—trauma-focused care principles are to be aware of the widespread impact of trauma; understand paths for recovery; recognize signs and symptoms of trauma in patients, families, and even staff; respond in a way that incorporates knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices; and resist re-traumatization through avoiding harmful practices (eg, using restraints or seclusion rooms when not clearly indicated)79

Incorporate violence-prevention awareness and principles into the curriculum of medical students, residents, and other health care professionals

Prevent

Leverage health care system resources to create primary prevention programs. Some hospitals have sourced produce or goods from local business that employ disadvantaged populations as an attempt to address underlying socioeconomic determinants; others have used the health care system to provide job and skills training for high-risk youth. Some hospitals have funded community-based parenting or school-based classes that incorporate violence prevention76

Investigate new strategies for primary prevention (ie, to prevent violence from happening in the first place); more research is needed to better understand effective health care-based approaches

New incentives and opportunities have been created to improve identification and assistance of patients at risk of violence and those presently experiencing violence. With the passage of the Affordable Care Act, screening adolescent and adult women for interpersonal violence and counseling must now be covered by many health plans with no cost sharing for patients.75 Reimbursement rates and implementation details are likely to differ across plans, but this may facilitate identification of such patients and support on-going efforts. Large trials have shown little efficacy if the intervention for patients who screened positive for intimate partner violence involved providing them a resource list or informing their clinician with subsequent discussion and referral left to the discretion of the clinician.83,84 Programs that have followed a positive screen result with more intensive support, such as a clinic-based CBT intervention, have noted improved outcomes.85 One such program, which screened minority women at prenatal care clinics and then provided CBT, demonstrated a reduction in subsequent intimate partner violence (23.3% in intervention group vs 37.8% in control group overall follow-up interviews; intervention participants also gave birth to a lower proportion of infants with very preterm birth [1.5% vs 6.6%]).85 More research is needed to better identify elements of programs that most effectively assist individuals found to be experiencing intimate partner violence or to identify other novel strategies. For example, medical-legal partnerships, an approach that attempts to better integrate legal services for patients into clinical care, can potentially assist clinicians with interventions not typically considered by the medical community. For example, in 1 retrospective cohort study, at the 12-months follow-up, women who had obtained permanent protection orders had a rate of police-reported physical abuse that was 20% of those women without protection orders (rate of 2.9 incidents per 100 person-years in intervention vs 14.0 incidents per 100 person-years in control).86

Some health systems have also attempted to address underlying risk factors by various forms of community engagement. For example, hospital systems have funded school-based educational programs that attempt to modify early risk factors for violence.76 Other health care systems have begun to intentionally purchase produce, goods, or services from local businesses in high-risk communities in an attempt address underlying economic risk factors for violence involvement.76 These strategies represent early engagement of health care systems with more population-level preventive approaches; evaluation of such strategies is needed to best guide efforts.

Conclusions

The scientific literature indicates quite clearly that preventing interpersonal violence is strategic from a health and public health perspective. It is strategic because of the consistently documented high levels of violence to which young children, adolescents, and young adult women and men are exposed. Furthermore, exposure to violence plays an important role, not just in causing physical injuries and homicide, but also in the etiology of mental illness, chronic disease, and infectious diseases such as HIV. Thus, preventing exposure to violence can have downstream effects on a broad range of health problems. Finally, there is a substantial and rapidly growing evidence base on what works to prevent violence. This evidence suggests that priority should be given to interventions that can affect multiple forms of violence, particularly those that seek to prevent violence among children and youth. The effects of violence and the probability of involvement in future violence are dose dependent; thus, considerable gains can be made by early intervention.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental content at jama.com

CME Quiz at jamanetworkcme.com and CME Questions page 514

Author Contributions: Dr Sumner had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: All the authors.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Sumner, Mercy, Dahlberg, Hillis.

Drafting of the manuscript: All the authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All the authors.

Statistical analysis: Sumner.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Sumner, Hillis, Houry.

Study supervision: Sumner, Mercy, Hillis, Houry.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All the authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and none were reported.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Death rates for selected causes by 10-year age groups, race, and sex. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/mortality/hist290.htm. Accessed March 6, 2015.

- 3.Web-based injury statistics query and reporting system. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html. Accessed March 6, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Federal Bureau of Investigation. Uniform crime reports. https://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/ucr. Accessed March 6, 2015.

- 5.Harris A, Thomas S, Fisher G, Hirsch D. The lethality of criminal assault 1960–1999. Homicide Stud. 2002;6(2):128–166. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blumstein A, Wallman J. The Crime Drop in America. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, United Nations Development Program. Global Status Report on Violence Prevention 2014. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ingram D, Chen LH. Age-adjusted homicide rates, by urbanization of county of residence—United States, 2004 and 2013. MMWR Morb Mort Wkly Rep. 2015;64(5):133. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brener ND, Simon TR, Krug EG, Lowry R. Recent trends in violence-related behaviors among high school students in the United States. JAMA. 1999;282(5):440–446. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.5.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wildeman C, Emanuel N, Leventhal JM, Putnam-Hornstein E, Waldfogel J, Lee H. The prevalence of confirmed maltreatment among US children, 2004 to 2011. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(8):706–713. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finkelhor D, Jones L, Shattuck A, Seito K. Updated Trends in Child Maltreatment, 2012. Durham, NH: Crimes Against Children Research Center; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farst K, Ambadwar PB, King AJ, Bird TM, Robbins JM. Trends in hospitalization rates and severity of injuries from abuse in young children, 1997–2009. Pediatrics. 2013;131(6):e1796–e1802. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leventhal JM, Gaither JR. Incidence of serious injuries due to physical abuse in the United States: 1997 to 2009. Pediatrics. 2012;130(5):e847–e852. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Catalano S. Intimate Partner Violence: Attributes of Victimization, 1993–2011. Washington, DC: US Dept of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Planty M, Langton L, Krebs C, Berzofsky M, Smiley-McDonald H. Female Victims of Sexual Violence, 1994–2010. Washington, DC: US Dept of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Acierno R, Hernandez MA, Amstadter AB, et al. Prevalence and correlates of emotional, physical, sexual, and financial abuse and potential neglect in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(2):292–297. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.163089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Basile KC, Walters ML, Chen J, Merrick MT. Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence victimization—national intimate partner and sexual violence survey, United States, 2011. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2014;63(8):1–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.US Department of Health & Human Services, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. Child maltreatment. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment. Accessed May 6, 2015.

- 19.Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Shattuck A, Hamby SL. Violence, crime, and abuse exposure in a national sample of children and youth: an update. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(7):614–621. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheets LK, Leach ME, Koszewski IJ, Lessmeier AM, Nugent M, Simpson P. Sentinel injuries in infants evaluated for child physical abuse. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):701–707. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jennings WG, Piquero AR, Reingle JM. On the overlap between victimization and offending. Aggress Violent Behav. 2012;17:16–26. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klevens J, Simon TR, Chen J. Are the perpetrators of violence one and the same? J Interpers Violence. 2012;27(10):1987–2002. doi: 10.1177/0886260511431441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamby S, Finkelhor D, Turner H, Ormrod R. The overlap of witnessing partner violence with child maltreatment and other victimizations in a nationally representative survey of youth. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34(10):734–741. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moffitt TE, Krueger RF, Caspi A, Fagan J. Partner abuse and general crime. Criminology. 2000;38:199–231. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamby S, Finkelhor D, Turner H. Teen dating violence: co-occurrence with other victimizations in the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence (NatSCEV) Psychol Violence. 2012;2(2):111–124. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Millett LS, Kohl PL, Jonson-Reid M, Drake B, Petra M. Child maltreatment victimization and subsequent perpetration of young adult intimate partner violence: an exploration of mediating factors. Child Maltreat. 2013;18(2):71–84. doi: 10.1177/1077559513484821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stith SM, Liu T, Davies LC, et al. Risk factors in child maltreatment. Aggress Violent Behav. 2009;14:13–29. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lipsey MW, Derzon JH. Predictors of violent or serious delinquency in adolescence and early adulthood. In: Loeber R, Farrington DP, editors. Serious & Violent Juvenile Offenders. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 86–105. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Capaldi DM, Knoble NB, Shortt JW, Kim HK. A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse. 2012;3(2):231–280. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coulton CJ, Crampton DS, Irwin M, Spilsbury JC, Korbin JE. How neighborhoods influence child maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl. 2007;31(11–12):1117–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Gannon-Rowley T. Assessing “neighborhood effects”. Annu Rev Sociol. 2002;28:443–478. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beyer K, Wallis AB, Hamberger LK. Neighborhood environment and intimate partner violence. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2015;16(1):16–47. doi: 10.1177/1524838013515758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hong JS, Espelage DL. A review of research on bullying and peer victimization in school. Aggress Violent Behav. 2012;17(4):311–322. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eckenrode J, Smith EG, McCarthy ME, Dineen M. Income inequality and child maltreatment in the United States. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3):454–461. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hsieh CC, Pugh MD. Poverty, income inequality, and violent crime. Crim Justice Rev. 1993;18(2):183–202. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asal V, Brown M. A cross-national exploration of the conditions that produce interpersonal violence. Polit Policy. 2010;38(2):175–192. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heise LL, Kotsadam A. Cross-national and multilevel correlates of partner violence. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(6):e332–e340. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Priest N, Paradies Y, Trenerry B, Truong M, Karlsen S, Kelly Y. A systematic review of studies examining the relationship between reported racism and health and wellbeing for children and young people. Soc Sci Med. 2013;95:115–127. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Drake B, Jolley JM, Lanier P, Fluke J, Barth RP, Jonson-Reid M. Racial bias in child protection. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):471–478. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dahlberg LL, Potter LB. Youth violence. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(1 suppl):3–14. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime. Science. 1997;277(5328):918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.MacKenzie EJ, Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, et al. A national evaluation of the effect of trauma-center care on mortality. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(4):366–378. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa052049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jewkes RK, Dunkle K, Nduna M, Shai N. Intimate partner violence, relationship power inequity, and incidence of HIV infection in young women in South Africa. Lancet. 2010;376(9734):41–48. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60548-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect. PLoS Med. 2012;9(11):e1001349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hillis SD, Anda RF, Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Marchbanks PA, Marks JS. The association between adverse childhood experiences and adolescent pregnancy, long-term psychosocial consequences, and fetal death. Pediatrics. 2004;113(2):320–327. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.2.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.García-Moreno C, Riecher-Rössler A, editors. Violence Against Women and Mental Health. Basel, Switzerland: Karger; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Washington State Institute for Public Policy. Benefit-Cost Results. 2015 http://www.wsipp.wa.gov/BenefitCost?topicId=. Accessed June 5, 2015.

- 49.The Guide to Community Preventive Services. 2015 http://www.thecommunityguide.org/. Accessed June 5, 2015.

- 50.Furlong M, McGilloway S, Bywater T, Hutchings J, Smith SM, Donnelly M. Behavioural and cognitive-behavioural group-based parenting programmes for early-onset conduct problems in children aged 3 to 12 years. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2(2):CD008225. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008225.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Piquero AR, Farrington DP, Welsh BC, Tremblay R, Jennings WG. Effects of early family/parenting programs on antisocial behavior and delinquency. Campbell Syst Rev. 2008;11 doi: 10.4073/csr.2008.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Farrington DP, Ttofi MM. School-based programs to reduce bullying and victimization. Campbell Syst Rev. 2009;6 doi: 10.4073/csr.2009.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lipsey MW, Landenberger NA, Wilson SJ. Effects of cognitive-behavioral programs for criminal offenders. Campbell Syst Rev. 2007;6 doi: 10.4073/csr.2007.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dubowitz H, Feigelman S, Lane W, Kim J. Pediatric primary care to help prevent child maltreatment. Pediatrics. 2009;123(3):858–864. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dubowitz H, Lane WG, Semiatin JN, Magder LS, Venepally M, Jans M. The safe environment for every kid model. Pediatrics. 2011;127(4):e962–e970. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Katz J, Moore J. Bystander education training for campus sexual assault prevention. Violence Vict. 2013;28(6):1054–1067. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.vv-d-12-00113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Polanin JR, Espelage DL, Pigott TD. A meta-analysis of school-based bullying prevention programs’ effects on bystander intervention behavior. School Psych Rev. 2012;41(1):47–65. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Knox V, Miller C, Gennetian LS. Reforming welfare and rewarding work: a summary of the final report on the Minnesota Family Investment Program. Minnesota Department of Human Services; 2000. http://www.mdrc.org/publications/27/summary.html. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Costello EJ, Compton SN, Keeler G, Angold A. Relationships between poverty and psychopathology. JAMA. 2003;290(15):2023–2029. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.15.2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kuo FE, Sullivan WC. Aggression and violence in the inner city. Environ Behav. 2001;33:543–571. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Branas CC, Cheney RA, MacDonald JM, Tam VW, Jackson TD, Ten Have TR. A difference-in-differences analysis of health, safety, and greening vacant urban space. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(11):1296–1306. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kaminski JW, Valle LA, Filene JH, Boyle CL. A meta-analytic review of components associated with parent training program effectiveness. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2008;36(4):567–589. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bilukha O, Hahn RA, Crosby A, et al. Task Force on Community Preventive Services The effectiveness of early childhood home visitation in preventing violence. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(2 suppl 1):11–39. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Spoth RL, Redmond C, Shin C. Reducing adolescents’ aggressive and hostile behaviors. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(12):1248–1257. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.12.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schweinhart LJMJ, Xiang Z, Barnet WS, Belfield CR, Nores M. Lifetime Effects: The HighScope Perry Preschool Study Through Age 40. Ypsilanti, MI: The HighScope Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reynolds AJ, Robertson DL. School-based early intervention and later child maltreatment in the Chicago Longitudinal Study. Child Dev. 2003;74(1):3–26. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reynolds AJ, Temple JA, Robertson DL, Mann EA. Long-term effects of an early childhood intervention on educational achievement and juvenile arrest. JAMA. 2001;285(18):2339–2346. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.18.2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hahn R, Fuqua-Whitley D, Wethington H, et al. Task Force on Community Preventive Services Effectiveness of universal school-based programs to prevent violent and aggressive behavior. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(2 suppl):S114–S129. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Foshee VA, Reyes LM, Agnew-Brune CB, et al. The effects of the evidence-based Safe Dates dating abuse prevention program on other youth violence outcomes. Prev Sci. 2014;15(6):907–916. doi: 10.1007/s11121-014-0472-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Anderson LM, Shinn C, St CJ, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Community interventions to promote healthy social environments. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2002;51(RR-1):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cancian M, Yang M, Slack KS. The effect of additional child support income on the risk of child maltreatment. Soc Serv Rev. 2013;87(3):417–437. [Google Scholar]

- 72.MacDonald J, Golinelli D, Stokes RJ, Bluthenthal R. The effect of business improvement districts on the incidence of violent crimes. Inj Prev. 2010;16(5):327–332. doi: 10.1136/ip.2009.024943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Haegerich TM, Dahlberg LL. Violence as a public health risk. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2011;5:392–406. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Feder G, Davies RA, Baird K, et al. Identification and Referral to Improve Safety (IRIS) of women experiencing domestic violence with a primary care training and support programme. Lancet. 2011;378(9805):1788–1795. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61179-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Family Violence Prevention and Services Program. The Affordable Care Act: an FAQ guide for domestic violence advocates and survivors. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/fysb/resource/fvpsa-aca-facts. Accessed March 6, 2015.

- 76.Health Research & Educational Trust. Hospital approaches to interrupt the cycle of violence. Health Research & Educational Trust; http://www.hpoe.org/violenceprevention. Published March 2015. Accessed March 6, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stein BD, Jaycox LH, Kataoka SH, et al. A mental health intervention for schoolchildren exposed to violence. JAMA. 2003;290(5):603–611. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.5.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Florence C, Shepherd J, Brennan I, Simon T. Effectiveness of anonymized information sharing and use in health service, police, and local government partnership for preventing violence related injury. BMJ. 2011;342:d3313. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. (Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884). [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cooper C, Eslinger DM, Stolley PD. Hospital-based violence intervention programs work. J Trauma. 2006;61(3):534–537. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000236576.81860.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Walton MA, Chermack ST, Shope JT, et al. Effects of a brief intervention for reducing violence and alcohol misuse among adolescents. JAMA. 2010;304(5):527–535. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.World Health Organization. Responding to Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Violence Against Women. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Klevens J, Kee R, Trick W, et al. Effect of screening for partner violence on women’s quality of life. JAMA. 2012;308(7):681–689. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.MacMillan HL, Wathen CN, Jamieson E, et al. McMaster Violence Against Women Research Group Screening for intimate partner violence in health care settings: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;302(5):493–501. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kiely M, El-Mohandes AA, El-Khorazaty MN, Blake SM, Gantz MG. An integrated intervention to reduce intimate partner violence in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2 pt 1):273–283. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181cbd482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Holt VL, Kernic MA, Lumley T, Wolf ME, Rivara FP. Civil protection orders and risk of subsequent police-reported violence. JAMA. 2002;288(5):589–594. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.5.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.