Abstract

Background

Non–ST-segment myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) can be complicated by high-degree atrioventricular (AV) block, asystole, or electromechanical dissociation (EMD), but these events are not well characterized in the contemporary era. This analysis assesses the incidence of and factors associated with these dysrhythmias in acute NSTEMIs.

Methods

Patients with NSTEMI in the EARLY ACS, PLATO, and TRACER trials were included in the pooled cohort (N = 29,677). Logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with in-hospital high-degree AV block and asystole or EMD, and Kaplan-Meier methods were used to assess mortality.

Results

High-degree AV block occurred in 112 (0.4%) patients, asystole in 157 (0.5%), and EMD in 38 (0.1%). Pacemakers were inserted in 241 patients (0.8%) during the index hospitalization: 30 (12%) for AV block. Among patients with high-degree AV block, we observed more frequent right coronary artery lesions (47% vs 29%). Age, diabetes, lower heart rate, and lower blood pressure were associated with high-degree AV block. Higher Killip class, ST-segment depression, prior myocardial infarction, and peripheral vascular disease were most strongly associated with asystole or EMD. Ten-day unadjusted survival was 90% for patients with high-degree AV block and 43% for those with asystole or EMD.

Conclusions

Although high-degree AV block, asystole, and EMD were infrequent complications of NSTEMI, they were associated with substantial short-term mortality. Only 1 in 8 pacemakers placed in NSTEMI patients during the acute hospitalization was for high-degree AV block.

Background

There are more than 1.5 million episodes of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in the United States annually.1 The proportion of ACS events that are ST-segment elevation myocardial infarctions (STEMI) has decreased over the past 10 years,2,3 whereas the incidence of non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) has been increasing.4,5

Ventricular arrhythmias are a recognized complication of ACS,6,7 but electromechanical dissociation (EMD) is the initially recognized rhythm in 1 of 3 ACS-related cardiac arrests.8 Furthermore, the incidence of ventricular tachycardia (VT) and ventricular fibrillation (VF) as the initial rhythm in an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest has decreased, whereas the incidence of EMD has increased.9,10 Asystole and EMD are also more common initial rhythms than VT/VF for in-hospital cardiac arrest.11,12 One-third of the asystole and EMD arrests take place among patients hospitalized for medical cardiac illness, and 15% to 20% of asystole and EMD arrests are among patients admitted with ACS.12 The relationship between NSTEMI and non-VT/VF cardiac arrests (asystole and EMD) has not been well defined.

High-degree atrioventricular (AV) block may necessitate pacemaker placement and is another complication of NSTEMI. Previous studies report complete heart block in 2% to 5%13–17 and pacemaker insertion in 1% to 4%13,18 of patients with myocardial infarction (MI). The rates of complete heart block among MI patients have decreased over time, but these data only included a single metropolitan area in the United States with data through 2005.18 The purpose of this investigation is to use a contemporary, multicenter, and international cohort of NSTEMI patients to identify the incidence, predictors, and outcomes of second- or third-degree AV block, asystole, and EMD after NSTEMI.

Methods

Study population

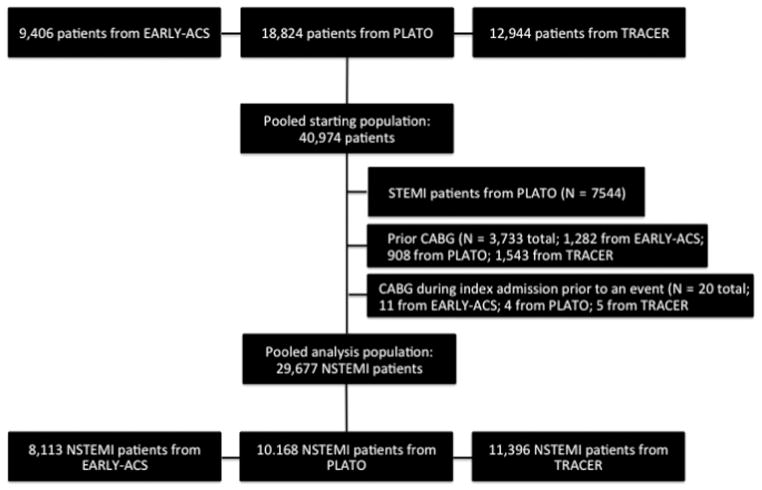

This analysis included patients with high-risk ACS without ST-elevation, who were enrolled in 3 large, international, randomized controlled studies performed between 2004 and 2010. The Early Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa Inhibition in Non–ST Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome (EARLY ACS) trial compared early use of eptifibatide precardiac catheterization vs after cardiac catheterization (delayed eptifibatide) in patients with NSTEMI.19 The Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial investigated the use of ticagrelor vs clopidogrel in patients with STEMI or NSTEMI.20 Finally, the Thrombin Receptor Antagonist for Clinical Event Reduction in Acute Coronary Syndrome (TRA-CER) trial evaluated vorapaxar compared with placebo in NSTEMI patients.21 A total of 40,974 patients were enrolled in these 3 clinical trials and were included in a pooled data set (Figure 1). The EARLY ACS and TRA-CER trials both included exclusively NSTEMI patients. Patients with STEMI on initial electrocardiogram (ECG) in the PLATO trial were excluded from this analysis (n = 7,544). Patients were also excluded if they had a history of cardiac surgery (n = 3,733) or had coronary artery bypass grafting during the index hospitalization and prior to AV block (n = 20), as cardiac surgery may predispose patients to conduction disease. Patients with pacemakers or defibrillators in situ at the time of randomization were not excluded because these patients were not identified at randomization in each of the 3 trials. After these 3 exclusions, there were 29,677 NSTEMI patients included in this analysis.

Figure 1.

Consort diagram that shows the starting population, excluded patients, and final analysis population.

End points

The end points of interest were time from randomization to in-hospital high-degree AV block (Mobitz type II or third-degree AV block), asystole, or EMD. Site investigators reported these end points. The number of asystole and EMD events was small and given that these conditions receive similar treatment, these end points were combined for the purposes of identifying factors associated with them and describing subsequent outcomes. Secondarily, we explored unadjusted survival after inhospital high-degree AV block and asystole or EMD event. Survival was based on all-cause mortality (both in-hospital and out-of-hospital). Placement of a permanent pacemaker during the index hospitalization was determined.

Statistical methods

Descriptive baseline statistics were determined with categorical variables reported as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables reported as medians with 25th and 75th percentiles. Logistic regression, stratified by enrolling trial, was used to identify factors associated with in-hospital development of high-degree AV block. Stepwise selection with a conservative entry and stay criteria (P < .10) created the final model from a list of candidate variables identified by the investigators based on data available across all 3 trials (Supplementary Material). Continuous variables were assessed for linearity assumptions prior to selection, and linear splines were applied as necessary. Results are presented as odds ratios, 95% CIs, and P values. After analyzing the primary end point of the binary occurrence of events, Kaplan-Meier plots were generated to visualize the timing of in-hospital AV block relative to trial randomization. Furthermore, among those with AV block, Kaplan-Meier plots describe time from AV block to mortality. Analyses were repeated for in-hospital asystole or EMD. Missing data rates were low (<2%). Complete case analyses were used.

All analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

EARLY ACS was supported by Schering-Plough and Millennium Pharmaceuticals. PLATO was supported by AstraZeneca. TRACER was supported by Merck.

Results

High-degree AV block and pacemaker implantation

Among the 29,677 NSTEMI patients, 112 (0.4%) developed high-degree AV block during hospitalization. These patients were older than the overall population (median 70 years vs 64 years) and were more likely to have diabetes (37% vs 28%), heart failure (12% vs 8%), and triple-vessel disease (33% vs 25%) (Table). Patients with high-degree AV block were also more likely to have the right coronary artery as the infarct-related artery (47% vs 29%). Of the 112 cases of high-degree AV block, 30 patients (27%) received pacemakers during the index hospitalization. High-degree AV block accounted for 12% (n = 30/241) of pacemaker implantations during the index hospitalization. Site investigators in the PLATO trial provided detailed data on the indication for pacemaker, and 25% (n = 22/88) of PLATO patients received a pacemaker for high-degree AV block. Data on implantable cardioverter defibrillator during the index hospitalization was available for the 58 patients with high-degree AV block from PLATO and TRACER, and none of these patients received an implantable cardioverter defibrillator in place of a pacemaker during the index admission.

Table.

Baseline characteristics

| Variable | No events (n = 29,397) | High-degree AV block* (n = 112) | Asystole* (n = 157) | EMD* (n = 38) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (y), median (25th, 75th) | 64 (57, 72) | 70 (62, 76) | 72 (65, 79) | 71 (64, 76) |

| Female sex | 9255 (32%) | 33 (30%) | 64 (41%) | 15 (40%) |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 28 (25, 31) | 27 (24, 32) | 27 (23, 31) | 27 (25, 31) |

| White | 25,813 (88%) | 103 (92%) | 129 (83%) | 35 (92%) |

| Medical history | ||||

| Hypertension | 20,207 (69%) | 75 (67%) | 118 (75%) | 29 (76%) |

| Diabetes | 8309 (28%) | 41 (37%) | 58 (37%) | 13 (34%) |

| Killip classes II–IV | 2210 (8%) | 13 (12%) | 39 (25%) | 13 (34%) |

| EF < 50% | 5249 (46%) | 27 (48%) | 67 (64%) | 15 (58%) |

| Symptoms to randomization ≥2 d | 4376 (15%) | 7 (6%) | 11 (7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Randomization to catheterization ≥2 d | 3060 (17%) | 15 (19%) | 32 (25%) | 4 (14%) |

| Triple-vessel CAD | 6968 (25%) | 36 (33%) | 79 (57%) | 18 (60%) |

| Heart failure | 2414 (8%) | 13 (12%) | 29 (19%) | 8 (21%) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 1977 (7%) | 14 (13%) | 23 (15%) | 3 (8%) |

| Laboratory values | ||||

| Creatinine clearance (mL/min) | 85 (66, 108) | 70 (55, 98) | 64 (47, 89) | 63 (53, 88) |

| MI artery location | ||||

| RCA | 2982 (29%) | 25 (47%) | 9 (33%) | 0 (0%) |

| LAD | 4613 (44%) | 12 (23%) | 14 (52%) | 2 (67%) |

| LCx | 2709 (26%) | 15 (28%) | 4 (15%) | 1 (33%) |

| Medication use at time of event | ||||

| β-Blocker | 19,717 (67%) | 67 (60%) | 96 (62%) | 20 (54%) |

| ACE/ARB | 13,305 (45%) | 49 (45%) | 61 (40%) | 17 (46%) |

Abbreviations: BMI, Body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; EF, ejection fraction; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LCx, left circumflex artery; RCA, right coronary artery.

Events are not mutually exclusive because patient could have had more than 1 in-hospital event.

Asystole and EMD

There were 157 (0.5%) cases of asystole and 38 (0.1%) episodes of EMD. Similar to patients with high-degree AV block, patients with asystole or EMD were older than the overall population (median age 72 years for asystole and 71 years for EMD, and 64 years for overall population) (Table). Patients with asystole or EMD also had lower creatinine clearance and higher rates of heart failure, Killip class > I, and triple-vessel disease.

Factors associated with AV block or asystole and EMD

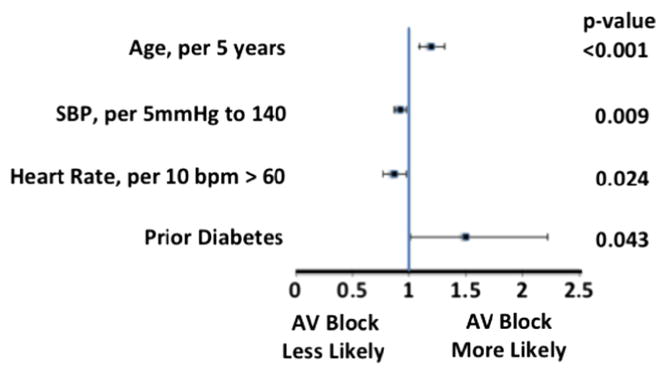

In multivariable modeling, faster heart rate was associated with lower rates of AV block (0.87 per 10 beats/min > 60 beats/min, 95% CI 0.77–0.98, P = .02) (Figure 2). There was no statistically significant association between heart rate < 60 beats/min and high-degree AV block. Diabetes and increasing age were associated with higher rates of AV block (1.50 [95% CI 1.01–2.22, P = .04] and 1.20 per 5 years [95% CI 1.09–1.31, P < .001], respectively). β-Blocker use was a candidate covariate that did not reach significance in the stepwise selection and was not included in the model.

Figure 2.

Forrest plot of factors associated with complete heart block.

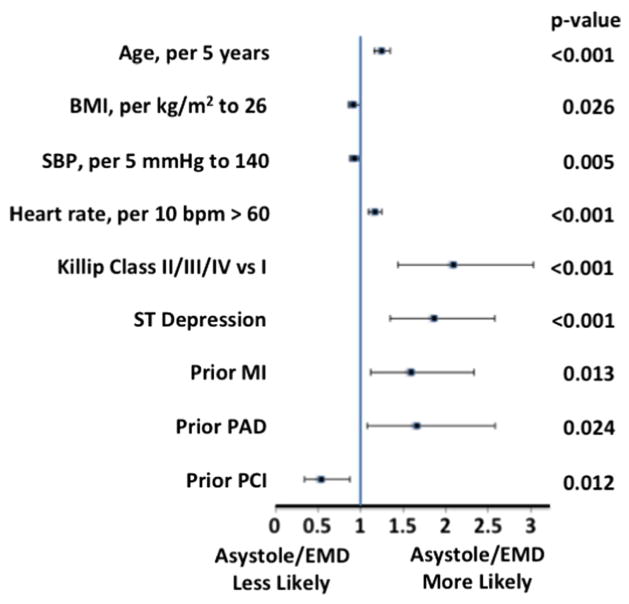

Increasing age was also associated with higher rates of asystole or EMD (1.25 per 5 years, 95% CI 1.16–1.35, P < .001) (Figure 3). Other factors that were associated with asystole or EMD included Killip class of II–IV, ST-segment depression on admission ECG, and heart rate > 60 beats/min. There was no statistically significant association between heart rate < 60 beats/min and asystole or EMD.

Figure 3.

Forrest plot of factors associated with EMD or asystole.

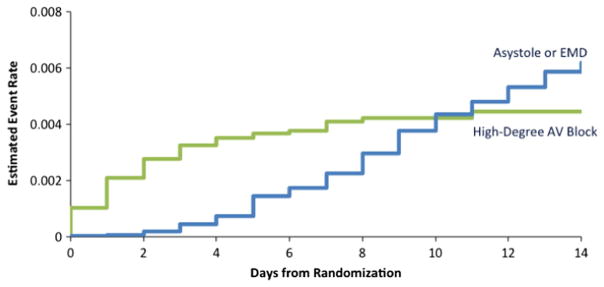

Timing of events

Within the first 4 days after randomization, nearly all of the high-degree AV block events had occurred, and the rate of in-hospital AV block remained stable at 0.4% after that time point (Figure 4). The timing of AV block contrasted with the timing of asystole or EMD. In-hospital asystole or EMD events increased in a linear fashion over the course of the first 14 days after randomization, and the rate of asystole or EMD did not surpass the rate of high-degree AV block until 10 days after hospitalization.

Figure 4.

Time from randomization to an event.

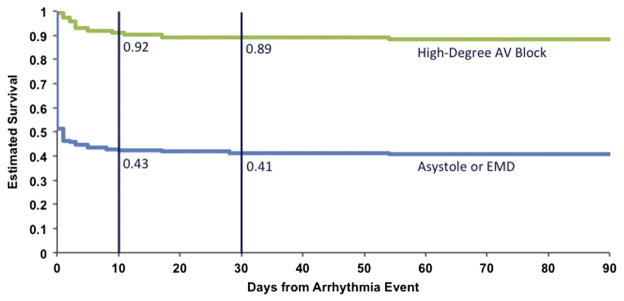

Acute and postdischarge survival

Patients sustaining an asystole or EMD cardiac arrest had worse survival than did patients with high-degree AV block (Figure 5). There was a nearly 50% immediate mortality associated with the asystole or EMD event, and the mortality increased to 57% at 10 days. This is in contrast to a 10-day mortality of 8% for in-hospital high-degree AV block. If patients survived until 10 days after a high-degree AV block or an asystole or EMD event, the survival rate remained stable out to 90 days.

Figure 5.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves demonstrating all-cause mortality for patients who developed high-degree AV block (green line) or asystole or EMD (blue line). Vertical lines at 10 and 30 days after the arrhythmia event highlight the 10- and 30-day rates of survival from all-cause mortality.

Discussion

The rates of NSTEMI are increasing, and this is one of the first analyses to look at non-VT/VF electrophysiologic complications among exclusively NSTEMI patients. In this pooled analysis of nearly 30,000 patients, we found that high-degree AV block, asystole, and EMD were all uncommon events among contemporary NSTEMI patients. Furthermore, pacemaker implantation was infrequent during the index hospitalization, and most of pacemaker implantation after NSTEMI was for AV block. Finally, we found that asystole and EMD were more common beyond the first 48 hours after an NSTEMI, whereas high-degree AV block was more common within the first 48 hours.

Our findings are consistent with a previous study of 278 ACS patients (91% NSTEMI patients) that identified a 1% rate of in-hospital asystole.22 Higher rates of asystole or EMD have been reported in STEMI.23 Rates of complete heart block have been previously reported as high as 2% to 5%,13–17 and this is in part due to inclusion of STEMI patients. In addition, as reperfusion and medical therapies improve over time, the incidence of AV block has decreased, as shown in the Worcester, MA population study, in which complete heart block decreased from 5.1% in 1975 to 2% in 2005.18 Regardless of the relatively low rates of these episodes among NSTEMI patients, they remain important clinical events due to their very high short-term mortality, as demonstrated in our analysis: 11% and 59% 30-day death rates in high-degree AV block and asystole or EMD, respectively.

The rate of pacemaker implantation during NSTEMI hospitalizations was also low, at 0.8% in our analysis. This is lower than the 1.3% pacemaker insertion rate in the Trandolapril Cardiac Evaluation (TRACE) trial,13 but nearly two-thirds of the patients in that trial were STEMI patients. Similar to our analysis, most patients who received pacemakers in the TRACE trial did not have complete heart block.13 Our analysis showed that only 12% of NSTEMI patients receiving a pacemaker had high-degree AV block. Although these trials did not record sinus node dysfunction in follow-up, it is reasonable to conclude that most patients received a pacemaker for sinus node dysfunction. Because these trials were focused on NSTEMI therapies, no data were available on the sinus node recovery, required pacing percentage, or long-term outcomes in these patients. The guidelines for device-based therapy from 2012 have recommendations on permanent pacing after a MI, but all guideline recommendations in ACS patients are for AV block.24 The 2014 NSTEMI guidelines do not recommend β-blockers or calcium-channel blockers in the setting of a PR interval greater than 0.24 seconds, second-degree AV block, or third-degree AV block.25 The device guidelines do list a pacemaker indication for patients with symptomatic bradycardia due to drug therapy, but this is not specific to ACS patients.24

Among patients who developed high-degree AV block in our analysis, approximately half of the events occurred within 24 hours of randomization, and about 75% of the AV block events were within 48 hours of randomization. This is consistent with previous findings, including a study of inferior STEMI patients in which 89% of complete heart block cases were seen within 24 hours of patient presentation.26 The patients in our analysis who developed asystole or EMD tended to have these events further out from randomization than the AV block events; most of these events occurred >48 hours after randomization.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this analysis. Patients had to meet the enrollment criteria of the clinical trials in order to be included in this analysis. However, this was a large population from 3 different clinical trial cohorts with each trial contributing nearly one-third of the patients in this analysis. Events were not recorded or tracked if they occurred before randomization or after hospital discharge from the index admission, so this analysis pertains to NSTEMI patients and in-hospital outcomes after enrollment in the trials. Site investigators reported the end points, and a blinded committee did not receive tracing and adjudicate the events, which could introduce misclassification bias. No ECG data were available regarding PR interval, QRS interval, or QRS morphology and intraventricular conduction delays, so we were unable to evaluate any relationship between these ECG data and subsequent AV block. There were 82 cases of high-degree AV block that did not receive pacemakers during the index hospitalization, and it is unknown what the timing of the resolution of AV block was in these patients, as well as how many received a pacemaker after index admission discharge.

Nondihydropyridine calcium-channel blocker use was not captured, so it was not included in the model for high-degree AV block. However, among NSTEMI patients, β-blockers were more likely to have been used than calcium-channel blockers, and β-blockers were included as a candidate covariate in the model. β-Blockers did not reach statistical significance in the stepwise covariate selection. There was a large amount of missingness for the infarct-related artery, so this was not included in the models as a covariate, but the baseline characteristics showed that patients with high-degree AV block were more likely than the overall population to have had a right coronary artery lesion. Peak cardiac enzymes could not be used as a marker for infarct size due to a high degree of missingness. Patients with pacemakers or defibrillators in situ at the time of randomization could not be excluded from the study population. Finally, differentiation between cardiovascular vs noncardiovascular death was not available in this analysis. Most deaths occurred near the time of the electrical events, suggesting that the deaths were likely related to the events under study.

Conclusions

Although high-degree AV block, asystole, and EMD were infrequent complications of NSTEMI, they were associated with substantial short-term mortality. Only 1 in 8 pacemaker implants in setting of NSTEMI was for high-degree AV block. High-degree AV block was more common within 48 hours of randomization, whereas asystole or EMD was more frequent beyond 48 hours after randomization.

Supplementary Material

Appendix. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2015.09.004.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Dr Pokorney reports modest research grant support from Astra Zeneca, Gilead, and Boston Scientific, and modest advisory board support from Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Ms Radder was supported by a National Institutes of Health training grant (T32HL079896). Dr Schulte and Dr Al-Khatib report no disclosures. Dr Tricoci reports a consultant agreement and research grant from Merck & Co., Inc. Dr Van de Werf reports research support from Merck & Co, Inc, and Boehringer Ingelheim; consultancy for AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim; and lecture fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and AstraZeneca. Dr James has received research grants from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Terumo Inc, Medtronic, and Vascular Solutions, and honoraria from The Medicines Company, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and IROKO, and has served as a consultant/advisory board member for AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Merck, Medtronic, and Sanofi. Dr Cannon currently receives research grant support from Accumetrics, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Sanofi-Aventis, and Schering Plough. Dr Armstrong reports research support and consulting fees/honoraria from Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp; consultancy for Eli Lilly, Regado Biosciences, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi-Aventis, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, and Merck & Co, Inc; and research support from Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi-Aventis Canada, GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Regado Biosciences, Amylin, and Novartis. Dr White reports research support from Sanofi-Aventis, Eli Lilly, The Medicines Company, the National Institutes of Health, Pfizer, Roche, Johnson & Johnson, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Daiichi Sankyo Pharma Development, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, and advisory boards for Merck Sharpe & Dohme and Regado Biosciences. Dr Califf has received consulting fees and grant support from Amylin, Kowa Research Institute, Merck-Schering Plough, Nile, NITROX LLC, Parkview, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, Orexigen Therapeutics, Pozen, Servier International, Johnson & Johnson, Roche, Merck, Regado, Bayer, and Web M.D. Dr Gibson has received consulting fees from Merck-Schering Plough. Dr Giugliano is a consultant to AstraZeneca, Biosite Inc, Biosite Diagnostics, CV Therapeutics, Daiichi Sankyo, Mosby, Novartis Pharmaceutical Company, Proctor and Gamble, Roche Diagnostic Corp, and Scios, and has received grant support from Adolor Corporation, AstraZeneca, BG Medicine, Biosite Inc, Biosite Diagnostics, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Medicure, Sanofi-Aventis, and Schering Plough Corporation. Dr Wallentin reports research support and consulting fees/honoraria from Merck & Co, Inc; consultancy for Regado Biotechnologies, Portola, C.S.L. Behring, Athera Biotechnologies, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Pfizer; and research support and lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, and Schering-Plough. Dr Mahaffey’s disclosures prior to August 1, 2013, are available at https://www.dcri.org/about-us/conflict-of-interest/Mahaffey-COI_2011-2013.pdf, and disclosures after August 1, 2013, are available at http://med.stanford.edu/profiles/Kenneth_Mahaffey. Dr Harrington has received consulting/advisory board fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi, Portola Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson, and Merck, and grant support from Eli Lilly/Daiichi-Sankyo, Merck, Portola Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, Johnson & Johnson, Bristol-Myers Squibb, The Medicines Company, and AstraZeneca. Dr Newby has received research grant funding for EARLY ACS through Duke/Duke Clinical Research Institute from Merck-Schering Plough, Amgen, Inc, Amylin, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Daiichi-Sankyo, dia Dexus, Bristol Myers Squibb, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Murdock Study, Regado Biosciences, NHLBI, Novartis, and Roche. Dr Piccini reports significant research grant support from ARCA biopharma, Boston Scientific, GE Healthcare, Johnson & Johnson/Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and ResMed; modest consultant/advisory board support from Medtronic, Inc, and Spectranetics, and significant consultant/advisory board support from Johnson & Johnson/Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

References

- 1.Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2012;126:e354–471. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318277d6a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:e2–220. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ac046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roe MT, Parsons LS, Pollack CV, Jr, et al. Quality of care by classification of myocardial infarction: treatment patterns for ST-segment elevation vs non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1630–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.14.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yeh RW, Sidney S, Chandra M, et al. Population trends in the incidence and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2155–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roger VL, Weston SA, Gerber Y, et al. Trends in incidence, severity, and outcome of hospitalized myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2010;121:863–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.897249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Khatib SM, Stebbins AL, Califf RM, et al. Sustained ventricular arrhythmias and mortality among patients with acute myocardial infarction: results from the GUSTO-III trial. Am Heart J. 2003;145:515–21. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2003.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piccini JP, White JA, Mehta RH, et al. Sustained ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation complicating non–ST-segment-elevation acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2012;126:41–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.071860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Virkkunen I, Paasio L, Ryynanen S, et al. Pulseless electrical activity and unsuccessful out-of-hospital resuscitation: what is the cause of death? Resuscitation. 2008;77:207–10. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cobb LA, Fahrenbruch CE, Olsufka M, et al. Changing incidence of out-of-hospital ventricular fibrillation, 1980–2000. JAMA. 2002;288:3008–13. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.23.3008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herlitz J, Andersson E, Bang A, et al. Experiences from treatment of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest during 17 years in Goteborg. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:1251–8. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nadkarni VM, Larkin GL, Peberdy MA, et al. First documented rhythm and clinical outcome from in-hospital cardiac arrest among children and adults. JAMA. 2006;295:50–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meaney PA, Nadkarni VM, Kern KB, et al. Rhythms and outcomes of adult in-hospital cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:101–8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b43282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aplin M, Engstrom T, Vejlstrup NG, et al. Prognostic importance of complete atrioventricular block complicating acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:853–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00900-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Archbold RA, Sayer JW, Ray S, et al. Frequency and prognostic implications of conduction defects in acute myocardial infarction since the introduction of thrombolytic therapy. Eur Heart J. 1998;19:893–8. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1997.0857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hreybe H, Saba S. Location of acute myocardial infarction and associated arrhythmias and outcome. Clin Cardiol. 2009;32:274–7. doi: 10.1002/clc.20357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lamas GA, Muller JE, Turi ZG, et al. A simplified method to predict occurrence of complete heart block during acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1986;57:1213–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rathore SS, Gersh BJ, Berger PB, et al. Acute myocardial infarction complicated by heart block in the elderly: prevalence and outcomes. Am Heart J. 2001;141:47–54. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.111259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen HL, Lessard D, Spencer FA, et al. Thirty-year trends (1975–2005) in the magnitude and hospital death rates associated with complete heart block in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a population-based perspective. Am Heart J. 2008;156:227–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giugliano RP, White JA, Bode C, et al. Early versus delayed, provisional eptifibatide in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2176–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1045–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tricoci P, Huang Z, Held C, et al. Thrombin-receptor antagonist vorapaxar in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:20–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winkler C, Funk M, Schindler DM, et al. Arrhythmias in patients with acute coronary syndrome in the first 24 hours of hospitalization. Heart Lung. 2013;42:422–7. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koeth O, Nibbe L, Arntz HR, et al. Fate of patients with prehospital resuscitation for ST-elevation myocardial infarction and a high rate of early reperfusion therapy (results from the PREMIR [Prehospital Myocardial Infarction Registry]) Am J Cardiol. 2012;109:1733–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update incorporated into the ACCF/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:e6–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non–ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:e139–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jim MH, Chan AO, Tse HF, et al. Clinical and angiographic findings of complete atrioventricular block in acute inferior myocardial infarction. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2010;39:185–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.