Abstract

Aims

Studies in guinea-pig cardiomyocytes show that reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by a few mitochondria can propagate to their neighbours, triggering synchronized, cell-wide network oscillations via an ROS-induced ROS release (RIRR) mechanism. How mitochondria in cardiomyocytes from failing hearts (HF) respond to local oxidative stress perturbations has not been investigated. Since mitochondrial ultrastructure is reportedly disrupted in HF, and propagation of ROS signals depends on mitochondrial network integrity, we hypothesized that the laser flash-induced RIRR is altered in HF.

Methods and results

To test the hypothesis, pressure-overload HF was induced in guinea pigs by ascending aortic constriction leading to left ventricular dilatation and decreased ejection fraction after 8 weeks. Isolated cardiomyocytes were studied with two-photon/confocal microscopy to determine their basal oxidative stress and propensity to undergo mitochondrial depolarization/oscillations in response to local laser flash stimulations. The expression of mitofusin proteins and mitochondrial network structure were also analysed. Results showed that HF cardiomyocytes had higher baseline ROS levels and less reduced glutathione, and were more prone to laser flash-induced mitochondrial depolarization. In contrast, the delay between the laser flash and synchronized cell-wide network oscillations was prolonged in HF myocytes compared with shams, and the spatial extent of coupling was diminished, suggesting dampened RIRR and ROS signal propagation. In addition, the expressions of mitofusin proteins in HF myocardium were down-regulated compared with these from sham-operated animals, and the mitochondrial network structure altered.

Conclusion

The disrupted inter-mitochondrial tethering and loss of structural organization may underlie decreased ROS-dependent mitochondrial coupling in HF.

Keywords: Mitochondrial network, Excitability, ROS-induced-ROS release, Heart failure, Mitofusin protein

Heart failure (HF) is a major health problem in the USA that affects about 5 million Americans. The incidence of HF is steadily increasing as the general population ages. Although the morbidity and mortality are high, the aetiology and detailed molecular mechanisms underlying the progression of HF remain incompletely understood, thereby hindering the development of effective preventative and therapeutic strategies.

Like other chronic human diseases, HF is multifactorial and is associated with complex genetic, metabolic, structural, and electrophysiological remodelling occurring at various spatial and temporal scales. For instance, a number of basic and clinical studies have demonstrated that the development of HF involves progressive alterations of ion channels/transporters underlying the action potential, Ca2+ handling, and excitation–contraction coupling (E-C coupling) that cause diminished contractile function.1–3 In addition, signalling pathways regulating cellular and cardiac functions, such as those modulated by reactive oxygen species (ROS), nitric oxide (NO), and Ca2+, are known to change significantly in failing hearts. Recently, mitochondrial dysfunction has emerged as a prominent contributing mechanism towards the development of HF. Intensive studies have convincingly demonstrated that functional (e.g. increased ROS production, diminished Ca2+ uptake, and impaired energy production) and structural alterations of these vital subcellular organelles are implicated in HF.4,5

In mammalian cells, mitochondria form highly dynamic networks with morphology varying by tissue and species, such as highly ordered, lattice-like in adult cardiac cells and irregular, tubular-like in neonatal cardiomyocytes and neurons. Regardless of their morphological variety, mitochondrial networks are formed and maintained by the interaction of fusion and fission events mediated by mitofusins (Mfn) such as Mfn1 and Mfn2 and fission proteins such as Drp1 and Fis1. Depletion of Mfn1 and/or Mfn2 has been shown to cause mitochondrial fragmentation and network disruption, leading to severe, or even lethal cellular dysfunction.6–9 Functionally, mitochondrial networks display highly non-linear, multiplicative, and collective dynamics that spans wide spatial and temporal scales. For instance, studies have shown that local laser flash-induced oscillations of a few mitochondria can entrain cell-wide, sustained network oscillations in isolated guinea-pig cardiomyocytes.10–12 Intriguingly, the oscillatory behaviours can be prevented or suppressed by pre-treating cells with an ROS scavenger, by blocking the inner membrane anion channel,10,13,14 or by increasing the distance between neighbouring mitochondria.12 These findings strongly support the notion that cardiac mitochondria form an excitable network capable of conveying ROS-induced ROS release (RIRR) signalling among mitochondria in the cytoplasm (see ref. 15 for review).

While mitochondrial RIRR in healthy cardiomyocytes has been intensively studied, how HF cardiac mitochondria respond to oxidative stress perturbations and exhibit network behaviour has yet to be examined. Here we hypothesized that mitochondrial tethering is impaired in HF cardiomyocytes, which impedes the propagation and regeneration of intracellular RIRR signalling, thereby diminishing the network excitability. We employed a guinea-pig HF model to compare the basal mitochondrial energetic state and the behaviour of mitochondrial network in response to local laser flash-induced oxidative stress in HF and sham cardiomyocytes. The data show that HF mitochondria exhibited a trend towards spontaneous ΔΨm collapse that was associated with a higher level of basal oxidative stress. Surprisingly, however, we found that in many HF cardiomyocytes ΔΨm depolarization/oscillations were not tightly coupled, that is, the mitochondrial clusters were less likely to participate in emergent network synchronization. The data suggest that decreased mitochondrial network excitability in HF cardiomyocytes might be attributed to the disrupted mitochondrial network ultrastructure and impaired mitochondrial functional tethering. These results shed light on understanding the interactions of mitochondria in failing guinea-pig hearts.

2. Methods

All protocols involving animals conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (PMID 21595115, revised 2011) and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at University of Alabama at Birmingham and the Johns Hopkins University.

2.1. Animal model

Adult guinea pigs were anaesthetized with 4% isoflurane and then intubated and ventilated with O2 and 1.5–2.5% isoflurane. After a left thoracotomy and pericardiectomy, ascending aortic constriction (AC) was produced with a 0.58-mm (i.d.) tantalum clip. Sham operation was performed following the same procedure except for clip application. When animals were breathing spontaneously after the procedure, bupronex (0.05 mg/kg) was administrated via intramuscular injection for analgesia. The progression of HF was monitored with echocardiography as described previously.16 Fractional shortening (FS) in the AC group started to decrease at 6 weeks after the banding surgery (44.2 ± 1.0% at week 0 vs. 38.4 ± 1.2% at week 6). Animals were sacrificed at week 8 when FS further decreased to 34% (29.3 ± 3.3%) and significant cardiac dysfunction was observed.

2.2. Cardiomyocyte isolation and fluorescent probe loading

Fresh guinea-pig ventricular myocytes were prepared by enzymatic dispersion as described previously.13,17 Briefly, HF or sham animals were anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (120 mg/kg I.P.). Following thoracotomy, hearts were quickly excised, mounted on a Langendorff apparatus, and perfused with collagenase-containing solution at 37°C. After isolation, cells were stored in a high K+ solution (in mmol/L: 120 glutamate, 25 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 1 EGTA, and pH 7.5 with KOH) temporarily before fluorescent dye loading. The cationic potentiometric fluorescent dye tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM) was used to monitor changes in mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm). The ROS level was monitored with H2DCF-DA (5 µmol/L), a hydrogen peroxide-sensitive fluorescent indicator, as described previously.10,13 To image the basal level or dynamics of ΔΨm and intracellular reduced glutathione (GSH) simultaneously, 100 nmol/L TMRM and 50 μmol/L monochlorobimane (MCB) were added to the external solution and allowed to equilibrate for 25 min at 37°C. The levels of GSH were determined by MCB's fluorescent product glutathione S-bimane (GSB) according to the reversible reaction: MCB + GSH ↔ GSB. To quantify the concentrations of GSH, in vitro calibrations were performed before imaging the cells loaded with MCB as described previously.18

2.3. Two-photon/confocal image acquisition and data analysis

The dish containing fluorescent dye-loaded cardiomyocytes was equilibrated at 37°C with unrestricted access to atmospheric oxygen on the stage of a microscope. For two-photon (Olympus FV 1000MPE) imaging, the excitation wavelength was set at 760 nm, which allowed simultaneous recording of fluorescent probes such as GSB and TMRM.18 A three-channel photomultiplier detector assembly with appropriate dichroic mirrors and band-pass filters was used to separate the fluorescence emissions of the blue (<500 nm for NADH or 480 nm for GSB), green (500–550 nm for H2DCF-DA), and red (580–630 nm for TMRM) indicators. For confocal microscope (Olympus FV 1000), 488 nm argon laser and 543 nm HeNe laser lines were used to image GSB and TMRM, respectively. To examine the dynamics of cardiac mitochondria in response to a local oxidative stress perturbation, a laser flash was applied to a small (∼64 µm3) region of the cell volume as described previously.10 Images were analysed using ImageJ software (Wayne Rasband, National Institutes of Health).

2.4. Protein and transcript expression analysis

Left ventricular homogenates were analysed by western blotting to compare the protein content of mitochondrial fusion (Mfn1, Mfn2, and OPA1) and fission (FIS1 and DRP1) proteins. Briefly, liquid nitrogen frozen ventricles isolated from sham and HF guinea pigs were homogenized in T-PER buffer containing (in mM): 50 potassium phosphate buffer, 300 sucrose, 0.5 DTT, 1 EDTA (pH 8.0), 300 PMSF, 10 NaF, and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (1:100). Samples (40 μg) were subjected to SDS–PAGE in NupagE 4–12% Bis–Tris gels. After electrophoresis, proteins were electro-transferred to a PVDF membrane. The blotted membrane was then blocked with TBS containing 5% fat-free milk powder and 0.1% Tween 20 for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with specific antibodies overnight at 4°C. Binding of the primary antibody was detected by autoradiography film (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA) after incubating blots with the peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (rabbit or mouse depending on the protein, 1:5000 for 1.5 h at room temperature). Quantification analysis of blots was performed with the AlphaView software (ProteinSimple, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Targeted bands were normalized to myocardial GAPDH.

Total RNA samples were extracted from the left ventricle tissue of sham and HF guinea pigs using RNAzol RT reagent (Molecular Research Center, Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA). cDNA were synthesized using a cDNA synthesis kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. Quantitative real-time RT–PCR analyses were carried out using the Roche SYBR green LightCycler 480 system (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) to determine the transcript levels of target genes. The amount of amplified product was calculated using the comparative CT method and normalized to endogenous GAPDH.

2.5. Immunohistochemistry

Guinea-pig hearts were immersion-fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin and paraffin embedded. Sections (5 μm) were mounted on slides, deparaffinized in xylene, and rehydrated in a gradient series of ethanol. After being blocked with 5% goat serum in 1% bovine serum in phosphate-buffered saline, they were incubated overnight at 4°C with Mfn1 (1:100) and ryanodine receptor (RyR2) (1:50) antibodies. Sections were washed, incubated for 1 h at room temperature with secondary antibodies Oregon Green 488 anti-rabbit IgG (1:600) and ATTO 647N anti-mouse IgG (1:200). Sections were washed again and mounted with Prolong (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA). Image acquisition and intensity measurements were performed on an Olympus IX81 microscope with Olympus Fluoview 1000 software (Olympus, Center Valley, PA, USA). Images were adjusted appropriately to remove background fluorescence.

2.6. Electron microscopy

For transmission electron microscopy, left ventricular tissue was isolated into longitudinal sections and placed in 0.1 mol/L cacodylate buffer containing 2% glutaraldehyde/paraformaldehyde, heat fixed for 30 min to cross-link proteins and aldehydes. Lipid fixation was performed using 2% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 mol/L cacodylate buffer and 1% aqueous uranyl acetate and tissue embedded in Epon. Transmission electron microscopy was performed at the UAB High Resolution Imaging Facility and longitudinal sections of tissue were assessed at the level of the ER/SR membrane, mitochondria, and contractile filaments.

2.7. Materials

Mouse monoclonal antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) (Mfn1 and OPA1), Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL, USA) (GAPDH, FIS1 and DRP1), and Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA) (Mfn2), respectively. ATTO 647N anti-mouse IgG was purchased from Active Motif (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Oregon Green 488 anti-rabbit IgG, TMRM, MCB, and MitoSox were purchased from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA). PVDF membrane and T-PER tissue protein extraction reagent were purchased from Thermo Scientifics (Waltham, MA, USA). All other reagents were from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA).

2.8. Statistics

Analysis and presentation of the data were performed using OriginLab software (Northampton, MA, USA). The present study included two groups of animals: the sham group and the HF group. In some experiments (such as cardiomyocyte GSH and ROS measurement), multiple samples (cells or mitochondria) from each animal were examined for replicating. For statistical analysis, those replicates were averaged within an animal so that each animal had only one value (i.e. the mean of the replicates). The statistical analysis was then performed at the animal level using those mean values (except for the western blot and RT–PCR data shown in Figure 4, which were analysed directly). As we were interested in the difference between the two groups (HF and sham) and not the difference among the individual animals within a group, the unpaired t-test was used. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Results are presented as mean ± SEM.

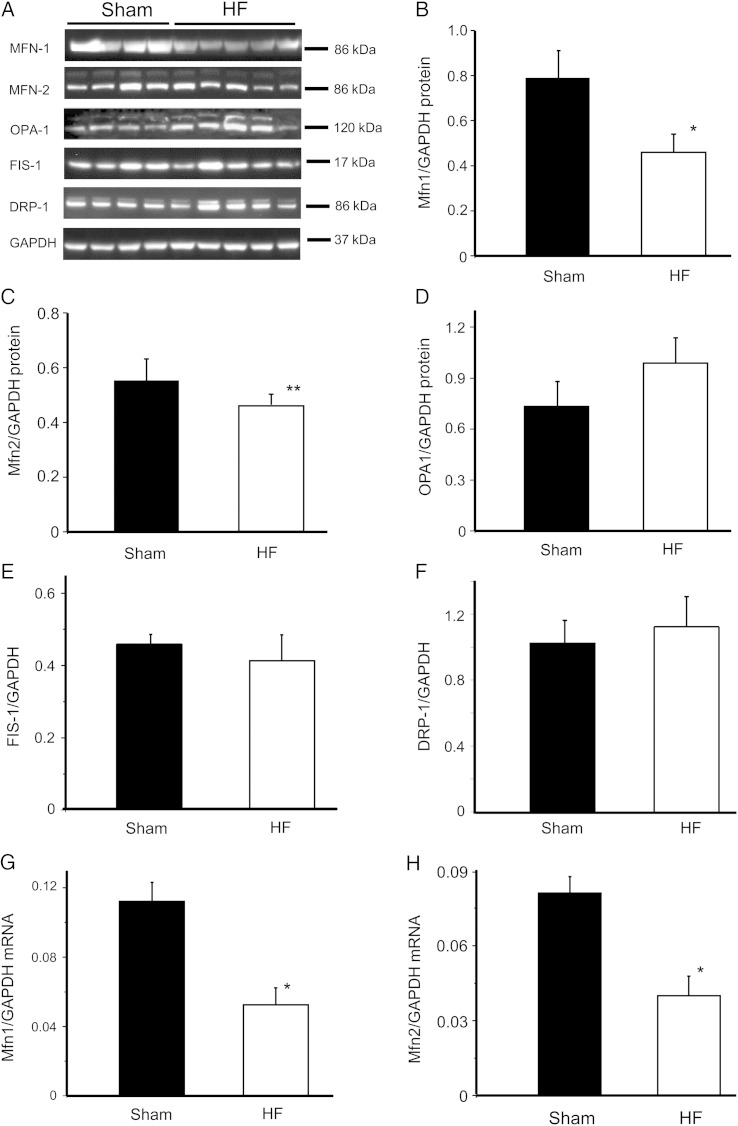

Figure 4.

Expression of mitofusin proteins in HF and sham myocardium. Western blot analysis (A) of the content of mitochondrial fusion proteins Mfn1 (B), Mfn2 (C), and (D) OPA1 and fission proteins FIS1 (E) and DRP1 (F) in samples of sham and HF left ventricles; and real-time PCR measurement of transcript level of Mfn1 (G) and Mfn2 (H) in samples from sham and HF hearts. The protein or mRNA expression was normalized to GAPDH. For the western blotting, samples from four different sham hearts and five different HF hearts were examined. For the PCR, four myocardium samples from each group were examined. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.1.

3. Results

3.1. Increased basal oxidative stress level in HF cardiomyocytes

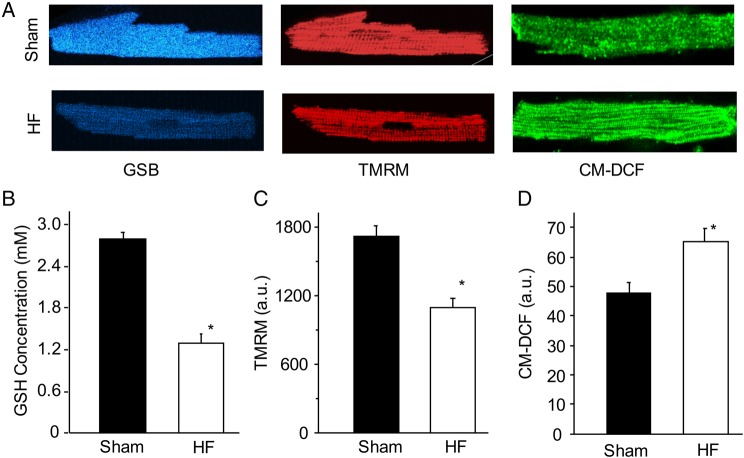

First, we examined and compared the basal energetic state of freshly isolated sham and HF cardiomyocytes by measuring intracellular ROS and GSH as well as NADH and mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) in the absence of electrical and laser stimulations. The basal GSH concentration, as determined by GSB fluorescence, was significantly lower in the HF cardiomyocytes when compared with shams (Figure 1A, left). Using the method described by Aon et al.18 we quantified the concentration of GSH, which was 53% lower in HF (2.76 ± 0.08 mM vs. 1.31 ± 0.09 mM, Figure 1B). In addition to the more oxidized glutathione redox pool, HF myocytes exhibited impaired mitochondrial membrane potential, as revealed by TMRM fluorescence (Figure 1A, middle) and summarized in Figure 1C. To further compare intracellular oxidative stress between the two groups, we measured the basal H2O2 (by CM-H2DCF, Figure 1A, right). The data showed that CM-H2DCF (a.u.) increased significantly in HF cells when compared with shams (47.5 ± 4.1 vs. 65.1 ± 4.3, P < 0.05) (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Comparison of basal mitochondrial energetic state in the sham and HF cardiomyocytes. (A) Representative sham (up) and HF (lower) cells loaded with MCB (left), TMRM (middle), or CM-H2DCFDA fluorescent dye. These dyes were used to measure intracellular reduced glutathione (GSH), mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), and H2O2, respectively; (B–D) Comparison of basal GSH concentration, ΔΨm, and CM-DCF between the sham and HF cardiomyocytes. A total of 40 cells from 5 sham hearts and 70 cells from 7 HF hearts were analysed. *P < 0.05.

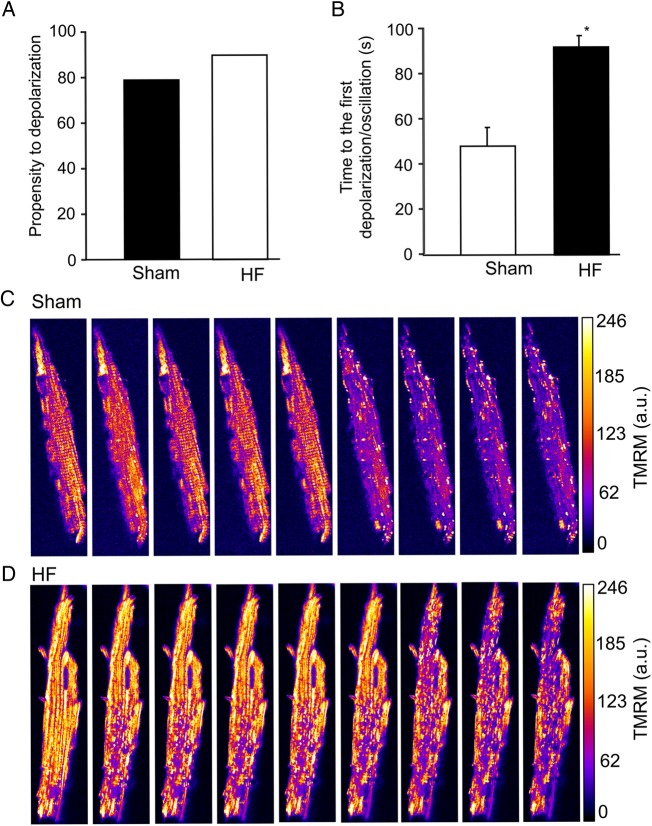

3.2. Mitochondrial network depolarization and oscillations in HF

Previous studies showed that a local laser flash triggered RIRR, causing cell-wide mitochondrial network depolarization/oscillations in freshly isolated healthy guinea-pig cardiomyocytes.10,13 In the present study, we examined how the local laser flash-induced oxidative stress could influence mitochondrial network of HF myocytes. Our results showed that, on average, there was a trend that HF mitochondria were more susceptible to oxidative stress than sham mitochondria. Specifically, nearly 92% (73 out of 80) of (originally polarized) HF myocytes lost the ΔΨm after being exposed to the laser flash (although the depolarization in many cells were not cell-wide and/or synchronious, see below for details), vs. about 80% of sham cells illuminated by the same setting of laser flash (Figure 2A). In addition, a fairly large portion (10–40%, varying by experiments) of HF cardiomyocytes was already partially or completely depolarized even before being exposed to the laser flash. These results are consistent with the higher basal intracellular oxidative stress level of HF cells. Interestingly, although the pre-disposition of HF cardiomyocytes to laser flash-induced ΔΨm depolarization was higher, HF cells took more time to reach cell-wide ΔΨm depolarization than shams (Figure 2B). As the network behaviour is mediated by RIRR, this suggested that the mitochondrial network was less excitable in HF. We also observed that the cluster size of synchronized depolarization of ΔΨm was smaller in HF myocytes. On average, about 75% mitochondria in sham cardiomyocytes depolarized after the induction by a laser flash (Figure 2C). In contrast, in some HF myocytes (started with fully polarized mitochondria), as many as 50% of mitochondria remained polarized, or depolarized only partially (Figure 2D). We analysed 12 cells from four to five animals for each group. An example of non-cell-wide mitochondrial depolarization in HF cardiomyocyte is shown in Supplementary material online, Movie S1.

Figure 2.

Local laser flash-induced mitochondrial depolarization in the HF and sham cardiomyocytes. (A) Propensity of cardiomyocytes to depolarize. (B) Lag between the first cell-wide mitochondrial depolarization and the induction of a laser flash. (C) Representative sham cardiomyocyte depolarization. (D) Representative HF cardiomyocyte depolarization. A total of 40 cells from 5 sham hearts and 80 cells from 7 HF hearts were analysed. *P < 0.05.

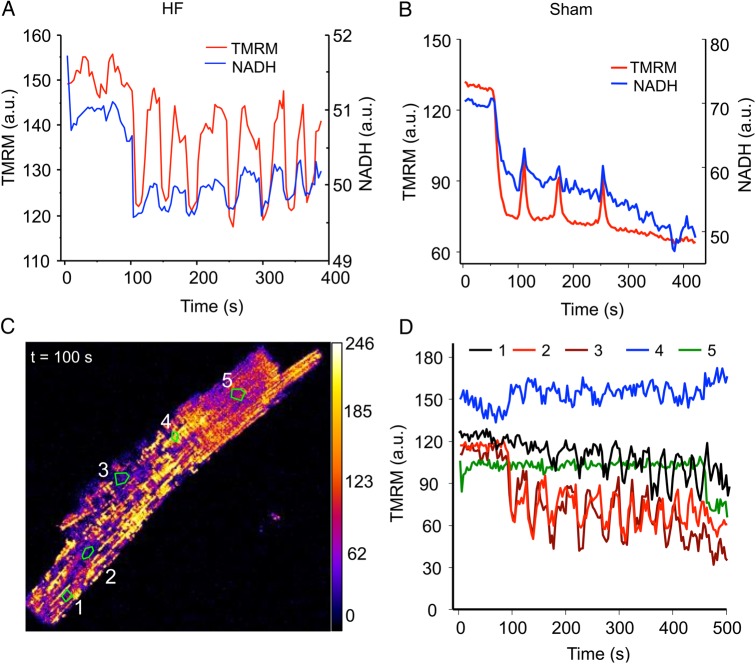

Regarding mitochondrial oscillations, in ∼60% of HF myocytes, the mitochondrial network failed to repolarize after the laser flash-induced depolarization (i.e. their ΔΨm collapsed permanently), whereas in the sham group, this number was less than 20%, suggesting that it is more difficult for HF mitochondria to recover after depolarization. The low propensity to repolarize was especially evident in those cells with highly unsynchronized or fragmented depolarization pattern. With that being said, some HF cells did exhibit sustained mitochondrial network oscillations (Figure 3A) that were similar to these observed in shams (Figure 3B), which involved cyclic changes in ΔΨm and NADH (Figure 3A) as well as ROS production and GSH depletion (data not shown). Interestingly, we also observed that about 11% of HF myocytes oscillated spontaneously in the absence of laser flash illuminations (see Supplementary material online, Movie S2 for an example, the spontaneously oscillated cell is marked by the arrow). The average oscillatory period (∼75 s, spanning from 30 to 100 s) and relative decrease in ΔΨm (∼30–40%) during each depolarization were comparable between HF and sham groups. One difference was that, in many HF myocytes, the mitochondrial oscillations were not very synchronous, as shown in Figure 3C (and Supplementary material online, Movie S3). In Figure 3D, the dynamics of several representative mitochondrial clusters that show unsynchronized behaviour were plotted. We can see that although majority of the mitochondrial population oscillated in response to a laser flash, the oscillation frequencies and amplitudes varied among clusters (and probably individual mitochondria) (represented by curves 1–3). In addition, there were many ‘mitochondrial cluster islands’ (4 and 5 in Figure 3C) that were refractory to the RIRR and did not depolarize/oscillate at all (represented by curves 4 and 5 in Figure 3D) even though they were surrounded by oscillating mitochondria. These results further suggested the diminished inter-mitochondrial connectivity in HF cardiomyocytes.

Figure 3.

Uncoupled laser flash-induced mitochondrial network oscillations in HF cardiomyocytes. (A) Oscillations of an HF cardiomyocyte involving mitochondrial membrane potential (TMRM) and NADH; (B) oscillations of a sham cell; (C) the snapshot of an oscillating HF cardiomyocyte showing heterogeneous mitochondrial energetic state; and (D) plots of time profile of membrane potential (measured by TMRM) of various mitochondrial clusters (curves 1–5 represent zones 1–5 marked in C). A total of 30 cells from 5 sham hearts and 40 cells from 7 HF hearts were examined.

3.3. Mitochondrial fusion/fission protein and transcript expression

Previous studies implicated that the laser flash-induced cell-wide mitochondrial network oscillations are mediated by the propagation of local ROS regeneration among neighbouring mitochondria. To examine whether the less-coupled mitochondrial depolarization/oscillations in HF myocytes are attributed to the impairment of network tethering, we analysed the expression of mitofusin proteins in left ventricular tissue by western blots. The data showed that the expression of Mfn1 protein (normalized to GAPDH) decreased significantly in HF myocardium when compared with sham (0.79 ± 0.12 vs. 0.46 ± 0.08, P < 0.05) (Figure 4A). Similarly, the expression of Mfn2 protein in HF myocardium also declined (from 0.63 ± 0.15 to 0.43 ± 0.12, P < 0.1) (Figure 4B), although the down-regulation was not as significant as Mfn1. The expression of inner mitochondrial membrane fusion protein OPA1 (Figure 4D) and mitochondrial fission proteins FIS1 (Figure 4E) and DRP1 (Figure 4F) were not significantly different between the sham and HF hearts. Alterations in mitochondrial fusion proteins at the transcript level were much more remarkable. Particularly, real-time PCR revealed that Mfn1 and Mfn2 mRNA expression decreased by 54 and 51%, respectively, in HF myocardium when compared with that in shams (Figure 4G and H).

3.4. Mitochondrial network ultrastructure

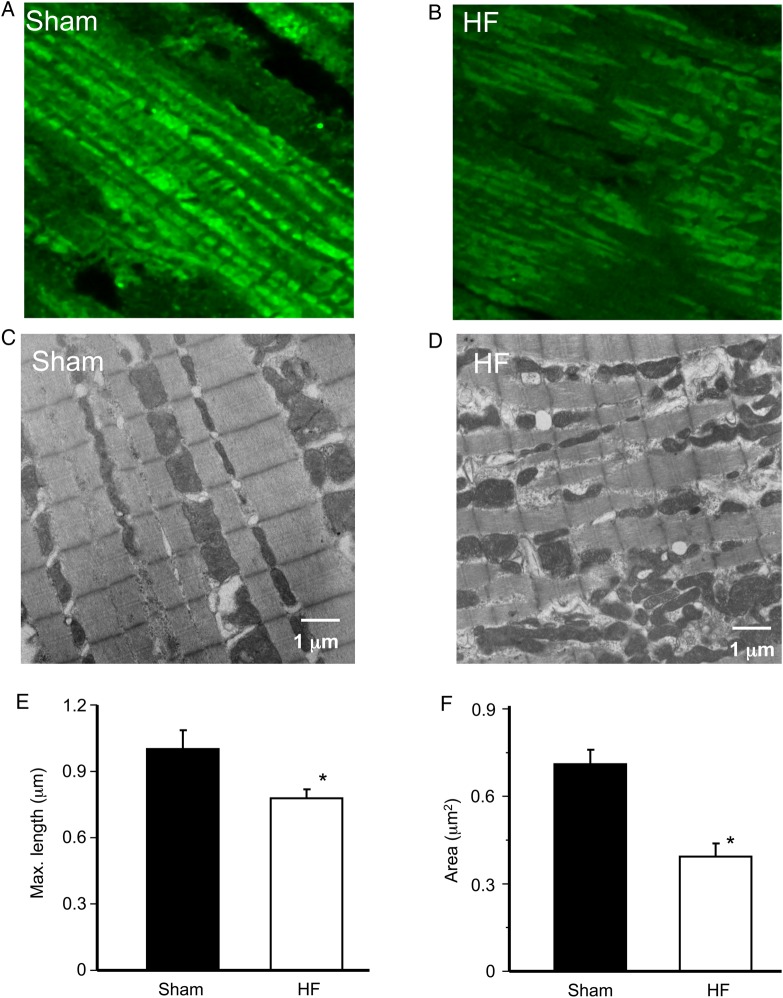

The expression of Mfn1 protein not only declined but also became heterogeneous in HF myocardium, as revealed by the IHC study shown in Figure 5A (sham) and Figure 5B (HF). To investigate whether the alteration in Mfn1 protein expression influences cardiac mitochondrial network, we examined and compared the ultramicroscopic structure of left ventricles from sham and HF guinea pigs. As expected, mitochondria form an orderly linear array along sarcomere in the sham myocardium (Figure 5C). This highly organized ultrastructure network was disrupted in the HF hearts. Particularly, HF mitochondria became fragmented and lost their linear register, and had a more disorganized pattern (Figure 5D). In addition, although in most of the field mitochondria were round, there were some crowded clusters of mitochondria with poorly defined morphologies (data not shown). Detailed analysis of the mitochondrial dimensions showed that HF mitochondria were smaller when compared with shams. Specifically, the maximal length of HF cardiac mitochondria reduced from 1.02 + 0.08 to 0.72 ± 0.09 µm (P < 0.05) (Figure 5E) and the cross-sectional area decreased from 0.77 ± 0.04 to 0.42 ± 0.08 µm2 (P < 0.05) (Figure 5F). The reduction in mitochondrial size and alteration in mitochondrial network structure were similar to those observed in Mfn1 KO mouse heart19 and other HF studies.20–22

Figure 5.

Mitochondrial ultrastructure in sham and HF left ventricular myocardium. (A) Confocal imaging of Mfn1 immunohistochemistry in sham myocardium; (B) confocal imaging of Mfn1 immunohistochemistry in HF myocardium; (C) transmit electron microscope (TEM) of sham mitochondria; (D) TEM of HF mitochondria; (E) averaged maximal length (or diameter) of mitochondria; and (F) averaged area of mitochondria. Approximately 120 mitochondria from 4 different sham hearts and ∼200 mitochondria from 5 different HF hearts were analysed. *P < 0.05.

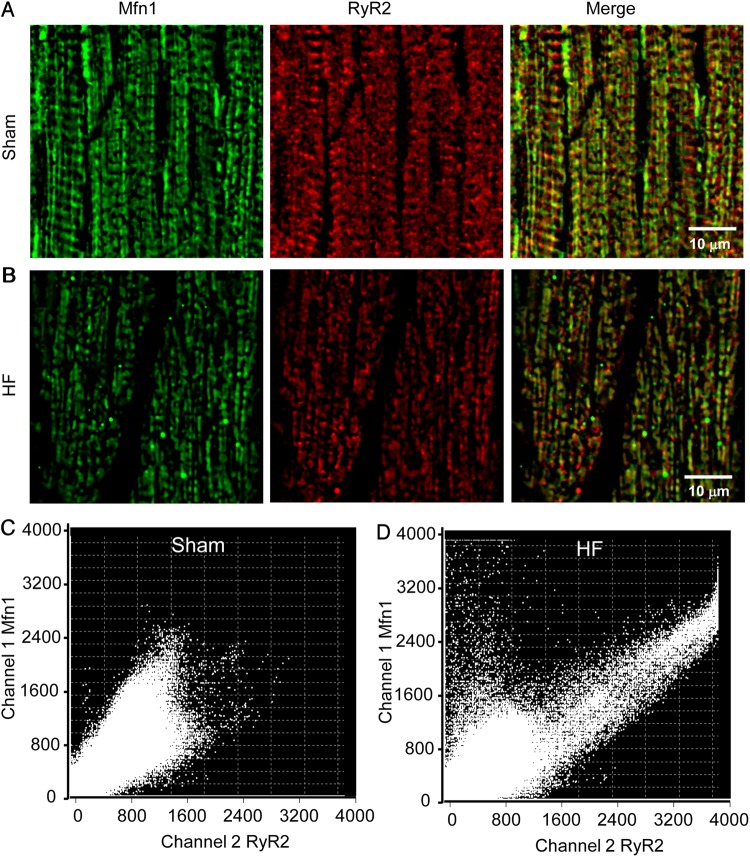

As mitofusin proteins also connect mitochondria and SR, altered Mfn1 and Mfn2 expressions in HF might affect the SR-mitochondria interorganellar tethering. This was examined by staining mitochondrial (e.g. Mfn1) and SR (e.g. RyR2) proteins and analysing protein colocalization using confocal microscopy (Figure 6). We can see that the expression of Mfn1 (and RyR2) decreased in HF myocardium (Figure 6A) when compared with that in sham (Figure 6B), which was consistent with the western blots and RT–PCR analysis. In addition, the colocalization analysis using FV10-ASW software showed that the mitochondria-SR tethering is disrupted in HF myocytes when compared with that in sham cells (Figure 6C and D). Particularly, there is a population of Mfn1 that was not associated with RyR2 (as indicated by the cloud of points in the upper left quadrant of Figure 6D), while the correlation between two signals became tighter in other parts of the cell. It is worthy to note that the resolution of confocal localization is limited and a superresolution imaging method such as immunogold EM or stimulated emission depletion nanoscope23 might be needed to make a firmer conclusion.

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemistry analysis of Mfn 1 (green) and RyR2 (red) colocalization in ventricular myocardium. (A) Sham; (B) HF. The colocalization of Mfn1 and RyR2 was analysed using Olympus FV10-ASW software and shown in C (sham) and D (HF), respectively. The results indicated that in HF not only the protein expressions were down-regulated but also the correlation between mitochondria and SR was altered. A total of six samples from three sham hearts and eight samples from four HF hearts were analysed.

4. Discussion

This study examines, for the first time, mitochondrial RIRR and oscillations in HF guinea-pig cardiomyocytes. The main findings are that when compared with sham: (i) HF cardiomyocytes had a high propensity to laser flash-induced ΔΨm depolarization; (ii) the ability of HF mitochondria to recover and support slow oscillations was diminished; (iii) the RIRR-mediated mitochondrial network depolarization/oscillations were less coupled and some mitochondrial clusters were refractory to laser flash-induced local oxidative stimulations (i.e. did not depolarize or oscillate); and (iv) the expression of mitofusin proteins, especially Mfn1, were down-regulated and the organization of mitochondria became disrupted, which might account for the less-coupled mitochondrial network behaviour and altered network excitability.

4.1. Mechanisms underlying uncoupled mitochondrial network behaviour in HF

Recent studies showed that isolated cardiomyocytes display cell-wide mitochondrial network depolarization/oscillations in response to local oxidative stress perturbations,10,24,25 suggesting that cardiac mitochondria form excitable networks capable of propagating ROS signalling. How this mitochondrial network behaviour alters under pathological conditions remains unclear. Using a pressure-overload-induced guinea-pig HF model, here we showed that failing cardiomyocytes were more prone to laser flash-induced ΔΨm depolarization than shams. However, the depolarized HF cardiac mitochondria were fairly refractory to repolarization and oscillations. The inability of HF mitochondria to recover and oscillate is likely attributed to excessive basal oxidative stress, which raises the probability of opening energy dissipating mitochondrial ion channels and irreversible mitochondrial collapse. In consistent with our observations, a wealth of evidence from animal and human studies has demonstrated increased ROS generation in HF,26,27 mainly by the mitochondria. Studies have shown that mice overexpressing catalase targeted to mitochondria, but not mice overexpressing wild-type peroxisomal catalase, are resistant to Gαq overexpression-induced HF.28 The oxidative stress in HF could also be caused by the antioxidant deficit. Although we did not measure the activities and expression of ROS scavenging enzymes in the present study, Hill et al. reported that catalase and glutathione peroxidase activities are reduced significantly in myocardial infarction-induced HF.29 It is worth to mention that the impairment of ROS scavenging may depend on the model of HF, as others have shown that in pacing-induced HF there were no significant changes in the activities of superoxide dismutase and catalase.30 First and foremost recently we have shown that impaired NAD(P)H supply, secondary to altered mitochondrial Ca2+ signalling, is a major component of ROS scavenger dysfunction in this model,16 and that correction of this deficit can prevent HF progression and sudden death in a related guinea-pig HF model.31,32 The direct relation between mitochondrial Ca2+, NAD(P)H oxidation, and ROS emission in HF guinea-pig hearts has also been reported and discussed by Kohlhass et al.33 Despite the advancements, more systematic studies of the components of intracellular ROS production and scavenger systems will be needed to understand the precise mechanisms linking oxidative stress and altered mitochondrial behaviours in HF.

Another intriguing finding is that mitochondrial depolarization in HF cardiomyocytes was less synchronized when compared with sham cells, which can be another factor accounting for the low coherence of mitochondrial oscillations in HF. According to percolation theory, a spanning cluster forms when about 60% of mitochondria within the cell reach a threshold of oxidative stress in order to exhibit global emergent behaviour. We observed that in many HF cardiomyocytes about half of mitochondrial population was resistant to the local laser flash stimulation. In addition, in a computational analysis, Aon et al.34 showed that only those mitochondria belonging to the spanning cluster can take part in the global limit cycle oscillations. Therefore, our data implicated that in HF cells some mitochondria were ‘functionally’ and/or physically disconnected from others, forming isolated islands that do not communicate or talk to their neighbours within the spanning cluster by conveying the laser flash-induced ROS signals. Taken together, these observations suggest that (i) HF mitochondria, which are more susceptible to depolarization as individuals, respond to the local oxidative stress-induced depolarization independently, while the network is more resistant to synchronized behaviour and (ii) HF cardiomyocytes have impaired local neighbour–neighbour interaction between mitochondria via RIRR and decreased mitochondrial network excitability.

Several mechanistic hypotheses have been proposed to explain mitochondrial network excitability and depolarization wave propagation in isolated cardiomyocytes;11,35–37 however, it remains incompletely understood how the subsets of mitochondria communicate to achieve global response throughout the cell. Recently, using a computational mitochondrial network model, we showed that the rate and pattern of mitochondrial depolarization wave propagation in an oscillating cardiomyocyte is determined by the local generation and diffusion of ROS (i.e. ROS diffusion coefficient and/or the distance between neighbouring mitochondria).12,15 Interestingly, Papanicolaou et al. showed that the propagation of mitochondrial depolarization wave in the Mfn119 or Mfn238 knockout cardiomyocytes was significantly slower than that in wild-type cells. These findings suggest that the mitochondrial tethering (e.g. distribution and connectivity) mediated by mitofusin proteins plays an important role in regulating mitochondrial network excitability and a defect in the fission–fusion machinery could impair mitochondrial network behaviours. In support to this notion, we found in the present study that the expression of mitofusin protein, especially Mfn1, were lower in HF myocardium. In addition, Mnf1 expression became heterogeneous in some HF cardiomyocytes as revealed by the IHC experiments (Figures 5 and6). These alterations can account for the disruption of the lattice-like mitochondrial network organization and non-uniform distribution of mitochondrial clusters. Indeed, although adult cardiac myocyte mitochondria are limited in motility, studies have suggested that they undergo slow (∼16 days/cycle) fusion/fission.6 This turnover rate might increase under stress conditions that induce increased energetic demand and mitochondrial damages, such as reported by Piquereau et al.39 The resulting independent mitochondrial clusters that are functionally isolated from others in the cell can impede the propagation of the otherwise very active RIRR signals and generation of global network responses. This could explain the less-coupled mitochondrial oscillations and impaired mitochondrial network excitability observed in HF cardiomyocytes (Figure 3 and Supplementary material online, Movie S3).

4.2. Is impairment of mitochondrial network excitability good or bad?

Mitochondria lie at the crossroad of intracellular metabolic and signalling pathways and perform a great variety of important functions such as regulating cellular energy metabolism and mediating cell death and survival. Thus, under physiological conditions the integrity of mitochondrial network excitability is essential for efficiently conveying signalling molecules/ions and for synchronized energy production in mitochondria in response to changes in workload. However, propagation of pathological signals (e.g. excessive ROS or Ca2+) among mitochondria scales up to induce the failure of organellar network, leading to severe cellular and organ-level dysfunction. For instance, a series of experimental40 and computational41,42 studies have demonstrated that oxidative stress-induced cell-wide mitochondrial network dysfunction causes the opening of KATP channels, inducing cellular inexcitability and tissue electrical instability. Similarly, other studies have shown that ventricular arrhythmias induced by ROS exposure43 or depletion of intracellular GSH44 can be alleviated by stabilizing ΔΨm or preventing mitochondrial ROS propagation. Interestingly, a recent study showed that knockout of Mfn1 gene, which disrupted mitochondrial network organization, delayed H2O2-induced mitochondrial depolarization and permeability transition pore (mPTP) opening.19 Thus the impaired mitochondrial network excitability may protect the cells under certain conditions such as during stress. It should be mentioned that although short-term inhibition of mPTP can be protective, long-term inhibition of the pores might cause detrimental effects,39 as mPTP opening is also involved in physiological events such as ROS or Ca2+ signalling. Thus, impairment of mitochondrial excitability can be a double-edged sword. More studies, especially at the in vivo animal level, will be needed to understand more precisely how alterations of mitochondrial network connectivity could influence cellular and organ functions under physiological and pathological conditions.

In summary, we showed that the mitochondria of HF cardiomyocytes, when compared with the non-failing ones, have a higher propensity to depolarize but a lower tendency to recover in response to a laser flash stimulation. In addition, the HF mitochondria exhibit more unsynchronized network behaviours under oxidative stress conditions, suggesting HF-mediated mitochondrial functional heterogeneity and impaired network excitability.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Cardiovascular Research online.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01HL097176 to L.J.D., R01HL101235 and R37HL054598 to B.O'R., R00HL095648 and R01HL121206 to L.Z.).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mr Eddie Bradley, Dr Danielle Yancy, and Dr Helen E. Collins for their technical support, and Dr An-Chi Wei for the insightful discussion.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Bers DM, Despa S. Cardiac myocytes Ca2+ and Na+ regulation in normal and failing hearts. J Pharmacol Sci 2006;100:315–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mann DL. Mechanisms and models in heart failure: a combinatorial approach. Circulation 1999;100:999–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pieske B, Maier LS, Piacentino V III, Weisser J, Hasenfuss G, Houser S. Rate dependence of [Na+]i and contractility in nonfailing and failing human myocardium. Circulation 2002;106:447–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aiba T, Tomaselli GF. Electrical remodeling in the failing heart. Curr Opin Cardiol 2010;25:29–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stanley WC, Recchia FA, Lopaschuk GD. Myocardial substrate metabolism in the normal and failing heart. Physiol Rev 2005;85:1093–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y, Liu Y, Dorn GW II. Mitochondrial fusion is essential for organelle function and cardiac homeostasis. Circ Res 2011;109:1327–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia-Perez C, Hajnoczky G, Csordas G. Physical coupling supports the local Ca2+ transfer between sarcoplasmic reticulum subdomains and the mitochondria in heart muscle. J Biol Chem 2008;283:32771–32780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papanicolaou KN, Kikuchi R, Ngoh GA, Coughlan KA, Dominguez I, Stanley WC, Walsh K. Mitofusins 1 and 2 are essential for postnatal metabolic remodeling in heart. Circ Res 2012;111:1012–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Westermann B. Mitochondrial fusion and fission in cell life and death. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2010;11:872–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aon MA, Cortassa S, Marban E, O'Rourke B. Synchronized whole cell oscillations in mitochondrial metabolism triggered by a local release of reactive oxygen species in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem 2003;278:44735–44744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aon MA, Cortassa S, O'Rourke B. Percolation and criticality in a mitochondrial network. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:4447–4452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou L, Aon MA, Almas T, Cortassa S, Winslow RL, O'Rourke B. A reaction-diffusion model of ROS-induced ROS release in a mitochondrial network. PLoS Comput Biol 2010;6:e1000657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou L, Aon MA, Liu T, O'Rourke B. Dynamic modulation of Ca(2+) sparks by mitochondrial oscillations in isolated guinea pig cardiomyocytes under oxidative stress. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2011;51:632–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biary N, Xie C, Kauffman J, Akar FG. Biophysical properties and functional consequences of reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced ROS release in intact myocardium. J Physiol 2011;589:5167–5179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou L, O'Rourke B. Cardiac mitochondrial network excitability: insights from computational analysis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2012;302:H2178–H2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu T, O'Rourke B. Enhancing mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in myocytes from failing hearts restores energy supply and demand matching. Circ Res 2008;103:279–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Rourke B, Ramza BM, Marban E. Oscillations of membrane current and excitability driven by metabolic oscillations in heart cells. Science 1994;265:962–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aon MA, Cortassa S, Maack C, O'Rourke B. Sequential opening of mitochondrial ion channels as a function of glutathione redox thiol status. J Biol Chem 2007;282:21889–21900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papanicolaou KN, Ngoh GA, Dabkowski ER, O'Connell KA, Ribeiro RF Jr, Stanley WC, Walsh K. Cardiomyocyte deletion of mitofusin-1 leads to mitochondrial fragmentation and improves tolerance to ROS-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2012;302:H167–H179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sabbah HN, Sharov V, Riddle JM, Kono T, Lesch M, Goldstein S. Mitochondrial abnormalities in myocardium of dogs with chronic heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1992;24:1333–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beutner G, Sharma VK, Giovannucci DR, Yule DI, Sheu SS. Identification of a ryanodine receptor in rat heart mitochondria. J Biol Chem 2001;276:21482–21488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schaper J, Froede R, Hein S, Buck A, Hashizume H, Speiser B, Friedl A, Bleese N. Impairment of the myocardial ultrastructure and changes of the cytoskeleton in dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation 1991;83:504–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jans DC, Wurm CA, Riedel D, Wenzel D, Stagge F, Deckers M, Rehling P, Jakobs S. STED super-resolution microscopy reveals an array of MINOS clusters along human mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013;110:8936–8941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brady NR, Elmore SP, van Beek JJ, Krab K, Courtoy PJ, Hue L, Westerhoff HV. Coordinated behavior of mitochondria in both space and time: a reactive oxygen species-activated wave of mitochondrial depolarization. Biophys J 2004;87:2022–2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zorov DB, Filburn CR, Klotz LO, Zweier JL, Sollott SJ. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced ROS release: a new phenomenon accompanying induction of the mitochondrial permeability transition in cardiac myocytes. J Exp Med 2000;192:1001–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Belch JJ, Bridges AB, Scott N, Chopra M. Oxygen free radicals and congestive heart failure. Br Heart J 1991;65:245–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hill MF, Singal PK. Antioxidant and oxidative stress changes during heart failure subsequent to myocardial infarction in rats. Am J Pathol 1996;148:291–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dai DF, Johnson SC, Villarin JJ, Chin MT, Nieves-Cintron M, Chen T, Marcinek DJ, Dorn GW II, Kang YJ, Prolla TA, Santana LF, Rabinovitch PS. Mitochondrial oxidative stress mediates angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy and Galphaq overexpression-induced heart failure. Circ Res 2011;108:837–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hill MF, Singal PK. Right and left myocardial antioxidant responses during heart failure subsequent to myocardial infarction. Circulation 1997;96:2414–2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsutsui H, Ide T, Hayashidani S, Suematsu N, Utsumi H, Nakamura R, Egashira K, Takeshita A. Greater susceptibility of failing cardiac myocytes to oxygen free radical-mediated injury. Cardiovasc Res 2001;49:103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu T, Brown DA, O'Rourke B. Role of mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiac glycoside toxicity. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2010;49:728–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu T, Takimoto E, Dimaano VL, DeMazumder D, Kettlewell S, Smith G, Sidor A, Abraham TP, O'Rourke B. Inhibiting mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchange prevents sudden death in a Guinea pig model of heart failure. Circ Res 2014;115:44–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kohlhaas M, Liu T, Knopp A, Zeller T, Ong MF, Bohm M, O'Rourke B, Maack C. Elevated cytosolic Na+ increases mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species in failing cardiac myocytes. Circulation 2010;121:1606–1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aon MA, Cortassa S, O'Rourke B. The fundamental organization of cardiac mitochondria as a network of coupled oscillators. Biophys J 2006;91:4317–4327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brady NR, Hamacher-Brady A, Westerhoff HV, Gottlieb RA. A wave of reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced ROS release in a sea of excitable mitochondria. Antioxid Redox Signal 2006;8:1651–1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park J, Lee J, Choi C. Mitochondrial network determines intracellular ROS dynamics and sensitivity to oxidative stress through switching inter-mitochondrial messengers. PLoS One 2011;6:e23211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang W, Fang H, Groom L, Cheng A, Zhang W, Liu J, Wang X, Li K, Han P, Zheng M, Yin J, Wang W, Mattson MP, Kao JP, Lakatta EG, Sheu SS, Ouyang K, Chen J, Dirksen RT, Cheng H. Superoxide flashes in single mitochondria. Cell 2008;134:279–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Papanicolaou KN, Khairallah RJ, Ngoh GA, Chikando A, Luptak I, O'Shea KM, Riley DD, Lugus JJ, Colucci WS, Lederer WJ, Stanley WC, Walsh K. Mitofusin-2 maintains mitochondrial structure and contributes to stress-induced permeability transition in cardiac myocytes. Mol Cell Biol 2011;31:1309–1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Piquereau J, Caffin F, Novotova M, Prola A, Garnier A, Mateo P, Fortin D, Huynh le H, Nicolas V, Alavi MV, Brenner C, Ventura-Clapier R, Veksler V, Joubert F. Down-regulation of OPA1 alters mouse mitochondrial morphology, PTP function, and cardiac adaptation to pressure overload. Cardiovasc Res 2012;94:408–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akar FG, Aon MA, Tomaselli GF, O'Rourke B. The mitochondrial origin of postischemic arrhythmias. J Clin Invest 2005;115:3527–3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou L, Cortassa S, Wei AC, Aon MA, Winslow RL, O'Rourke B. Modeling cardiac action potential shortening driven by oxidative stress-induced mitochondrial oscillations in guinea pig cardiomyocytes. Biophys J 2009;97:1843–1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou L, Solhjoo S, Millare B, Plank G, Abraham MR, Cortassa S, Trayanova N, O'Rourke B. Effects of regional mitochondrial depolarization on electrical propagation: implications for arrhythmogenesis. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2014;7:143–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kusama Y, Bernier M, Hearse DJ. Singlet oxygen-induced arrhythmias. Dose- and light-response studies for photoactivation of rose bengal in the rat heart . Circulation 1989;80:1432–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown DA, Aon MA, Frasier CR, Sloan RC, Maloney AH, Anderson EJ, O'Rourke B. Cardiac arrhythmias induced by glutathione oxidation can be inhibited by preventing mitochondrial depolarization. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2010;48:673–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]