Abstract

Healthier foods initiatives (HFIs) by national food retailers offer an opportunity to improve the nutritional profile of packaged food purchases (PFPS). Using a longitudinal dataset of US household PFPs, with methods to account for selectivity of shopping at a specific retailer, we modeled the effect of Walmart’s HFI using counterfactual simulations to examine observed vs. expected changes in the nutritional profile of Walmart PFPs. From 2000 to 2013, Walmart PFPs showed major declines in energy, sodium, and sugar density, as well as declines in sugary beverages, grain-based desserts, snacks, and candy, beyond trends at similar retailers. However, post-HFI declines were similar to what we expected based on pre-HFI trends, suggesting that these changes were not attributable to Walmart’s HFI. These results suggest that food retailer-based HFIs may not be sufficient to improve the nutritional profile of food purchases.

INTRODUCTION

Food retailers are unique and critical allies in the fight against obesity.1, 2 In fact, since 2011, three of the US’ largest grocers have implemented “healthier foods initiatives” (HFIs) intended to improve the healthfulness of foods consumers purchase. These efforts most often consist of strategies to help consumers identify healthier options through shelf or front-of-package labels, and sometimes include additional measures, such as strategic price cut, product reformulation, or additional marketing initiatives. Such retailer-based strategies have major potential to improve the nutrient profile of what US households purchase and consume, not only because food stores in general provide the majority of daily energy for US children and adults,3, 4 but also because national trends towards chain stores and consolidation 5 means that a limited number of top retailers account for the majority of US food purchases.6

Yet, no independent work has evaluated whether a multi-component HFI at a major national retailer actually improves the nutritional profile of food purchases. One important case study is Walmart, which is the US’ largest food retailers,6 with over 80% of households shopping there in 2012 (unpublished data), and is one of the largest recipients of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) spending.7 In 2011, Walmart announced an HFI with the stated intent of helping consumers make healthier food purchases.8 The HFI included efforts to help consumers make healthier choices, including a front-of-package labeling system identifying items meeting certain nutrition criteria and strategic price reductions on healthier items. The HFI also included efforts to improve the healthfulness of the foods available, with goals to eliminate trans fat, reduce sodium by 25 percent, and added sugar by 10 percent in key product categories by 2015, (presumably achieved through the introduction of new products, removal of products, or reformulation).9

The goal of the present study is to use a natural experiment, capitalizing on observations of household packaged food purchases before and after implementation of Walmart’s HFI, to examine whether HFIs can improve the nutritional profile of packaged food purchases at major chain food retailers. However, there are a number of major challenges associated with examining HFIs at chain food retailers, especially using a natural experiment approach. To our knowledge, the only study that has examined a chain retailer-based initiative focused on a shelf labeling program, and found that use of a star icon shelf label was linked to significant but small (less than 2 percent) increases in the percent of purchases with a star icon after the intervention.10 However, this analysis simply examined the proportion of purchases with a star icon before and after implementation. This type of simple pre/post-intervention analysis cannot distinguish whether changes are attributable to the intervention, or to other concurrent secular trends that impacted food purchasing. In the case of Walmart, it is important to distinguish between ostensible HFI effects and other concurrent trends, including the “Great Recession,” the large increases in global food prices, or other shifts in the food retail environment, including industry-wide changes in product assortment or formulation.11, 12

In addition, lack of an appropriate control group can sometimes pose a major challenge to evaluating food retailer-based interventions. For example, two studies in the US and Scotland examining the impact of introducing a food retailer into food deserts on fruit and vegetable intake used controlled quasi-experimental designs, where the intervention community was matched to a “control” community on perceptions of food access, found that the intervention was not associated with increased fruit and vegetable intake,2, 13 whereas a similar intervention in Britain without a comparison found improvements in fruit and vegetable intake.14 Another study by Foster et al used a cluster-randomized study matching intervention and comparison stores based on sales from food-assistance programs and store size, to examine a 6-month, in-store marketing intervention to promote sales of healthier products.15 Yet, in the case of Walmart, no clear comparison group exists, as to the best of our knowledge, the intervention occurred in all Walmart stores at the same or nearly the same time, and there are no stores which remain “unexposed” to the intervention.

Ideally, we would observe the counterfactual: what would the nutritional profile of purchases look like if the HFI had not been enacted, holding all other factors constant? This approach was recently used by Ng et al to evaluate the Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation’s (HWCF) pledge to cut 1.5 trillion calories from the US food supply,16 but has not yet been applied to examine similar pledges by food retailers.

These evaluation efforts are further complicated by concerns about selectivity issues: as the retailer implements its HFI, it may attract more customers seeking out these new healthier food options. Thus, a key question is whether a retailer truly improved the nutrient profile of packaged food purchases (PFPs), or whether it simply attracted a more health-conscious consumer base.

The final challenge is determining the appropriate baseline period against which to measure these changes: since in a natural experiment, investigators do not implement an intervention but observe variation in response to natural events, it is not always obvious when the intervention occurred. In the present example, although Walmart formally announced their HFI in January of 2011, much of their online marketing suggests an earlier start date (i.e. “between 2008 and 2011 we removed 1.5 million pounds of salt across the commercial bread category”).9 While it is not uncommon for organizations to initiate changes in products prior to the formal beginning of a program or policy, as demonstrated by recent school lunch and menu labeling initiatives and many corporate voluntary initiatives,17-19 this ambiguity surrounding the implementation date is often overlooked.

The objective of this study is to examine whether Walmart’s HFI improved the nutritional profile of packaged food purchases (PFPs) from pre-HFI (2000-2010) to post-HFI (2011-2013), including densities of nutrients such as energy, sodium, and total sugar, as well as the contributions of key food groups. We conduct counterfactual simulations by comparing the projected pre-HFI trends in nutrient profile of Walmart PFPs to observed post-HFI trends in nutrient profile. We will also compare these to concurrent trends in PFPs at other chain retailers, to examine whether the HFI was associated with any changes above and beyond industry trends. We also examine whether results varied by whether Walmart’s stated pre-HFI period vs. a pre-HFI period as indicated by the data were used.

METHODS

Data

This study uses data on household PFPs from 2000 to 2013 from the Nielsen Homescan longitudinal dataset. Details of the sampling frame and methodology have been published elsewhere.20 In brief, households are sampled from 76 metropolitan and non-metropolitan US markets, and use a handheld scanner to record information on all PFPs. PFPs include all food and beverages with a bar code, including all consumer packaged goods and packaged fresh fruit and vegetables (e.g., a bag of lemons), but excluding unpackaged meat and produce (e.g., a single lemon).

In order to understand whether shifts in the nutrient profile of Walmart PFPs were above and beyond industry trends, we also examined shifts in PFPs from other chain retailers (i.e. chain grocery stores, supermarkets, and supercenters with at least 10 locations), who are the most comparable group of stores given their size and product assortment. Information on PFPs was linked at the UPC level to nutrition data from the Nutrition Facts Panel,21 updated annually, and includes both nationally-branded and store-brand products. However, due to contract agreements with our data vendors, we were unable to identify and examine store-brand products sold by specific retailers. Household-quarter observations were included for sample households that shopped for PFPs at Walmart (n= 1,212,803) or other chain retailers (n= 2,521,128) for at least two quarters. Demographic characteristics of the sample can be found in Appendix Exhibit 1.22

Nutrition Outcomes

Nutrient outcomes were evaluated separately for PFPs from Walmart and other chain retailers, and included density for energy (kcal/100 g), total sugar (g/100 g), saturated fat (g/100 g), and sodium (mg/100 g). A volume-based (/100g) relative measure was necessary to control for changes in the overall amount of PFPs purchased over time. We also examined shifts in percent volume purchased (percent g) from key food groups, including sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs), grain-based desserts, savory snacks (i.e., salty snack foods, such as chips or pretzels), candy, fresh/frozen fruit, and fresh/frozen vegetables.

Addressing selectivity

To deal with the potential selectivity of shopping at a given retailer over time, we created two sets of quarterly inverse probability weights to account for the likelihood of being a Walmart shopper or other chain retailer shopper, conditional upon variables associated with shopping these retailer types23.

In addition, we use fixed effects models examine average within-household effects over time. Fixed effects models can correct for selectivity if the likelihood of shopping at a certain retailer is associated with fixed characteristics of the household (e.g. income, race/ethnicity), since in the model each household essentially serves as its own control and thus these characteristics are differenced out.

Counterfactual simulation

We first identified potential dates when the HFI occurred by using switching regression 24 for both energy and sodium density of Walmart PFPs, since food industry initiatives to reduce sodium in processed foods began prior to Walmart’s HFI.25 For energy density, switching regression revealed a shift at 2011 as well as a shift at 2007 and 2013 (Appendix Exhibit 2)22. Sodium density showed switches in different directions at 2- and 3-year increments across the time period. Thus, for all models we examined both 2011 and 2007 as potential HFI initiation dates, since 2011 was Walmart’s stated initiation date and 2007 was the second most plausible date, given the 2008 date indicated in some of Walmart’s marketing materials.

Using these HFI start dates, we then tested the shape of the trend. In the energy, total sugar, and saturated fat models, we found that when using the 2011 HFI start date, a quadratic trend provided the best fit (based on model R2 and visual inspection), whereas when using the 2007 HFI start date, a linear trend provided the best fit. For the sodium model, a linear trend provided the best fit for the 2011 HFI start date, while a quadratic term provided the best fit for the 2007 start date. Models with the appropriate terms were then used for the remainder of analyses.

Statistical Analysis

We used fixed effects models to separately model all nutrient outcomes at Walmart and other chain retailers. All models included covariates to control for secular trends in the economic, food retail, and price environments, including average quarterly market-level unemployment rates,26 the weighted average of prices at each retailer type, and average market-level Walmart density (Walmart supercenters per 100,000 people).27, 28 Household-level covariates included household race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, and non-Hispanic Other),SNAP eligibility (≤130 percent federal poverty level), head of household education (≤ high school degree, some college, ≥ college degree), household type (single adult, multiple adults with no kids, adult(s) with kid(s)) and household composition (numbers of adults aged 19-49 and ≥50y, and numbers of children aged 0-5y, 6-18y).

To examine the observed nutrient profile of purchases pre-and post-HFI, Stata’s margins command was used to predict the mean nutrient density or percent volume from food groups for each year for each retailer. For models examining the counterfactual post-HFI nutrient profile, the pre-HFI time trend (2011 or 2007; linear or quadratic) for each nutrient outcome was estimated, then Stata’s predict command was used to predict mean nutrient outcomes during the post-HFI period. The observed mean nutrient profile was considered statistically significantly different from the counterfactual mean nutrient profile if 99 percent confidence intervals did not overlap (p<0.01). All statistical analyses were performed using Stata, version 13 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas).

Limitations

Several limitations precluded our ability to detect all potential HFI-related changes. For example, we would not examine the impact of specific HFI components, nor could we identify the “key categories” specifically designated by Walmart for reformulation (this is not public information). We also could not identify certain nutrients, like L fat, which was not required on nutrition labels before 2006, or added sugar, which under current regulations is neither required nor allowed on the nutrition facts panel, or nutrients like fiber, calcium, or iron. In addition, Homescan does not capture products without a barcode, including loose produce. Although unpackaged produce accounts for only approximately 2-3 percent of Walmart food expenditures in our sample, we still likely underestimated the effects of Walmart’s efforts to increase the availability and affordability of produce 29 on fruit and vegetable purchases. Finally, we could not explicitly examine Walmart store-brand products, which were a major focus of their efforts on product reformulation and labeling. We may have observed more substantial post-HFI declines if we had been able to distinguish store-brand PFPs from non-store-brand.

RESULTS

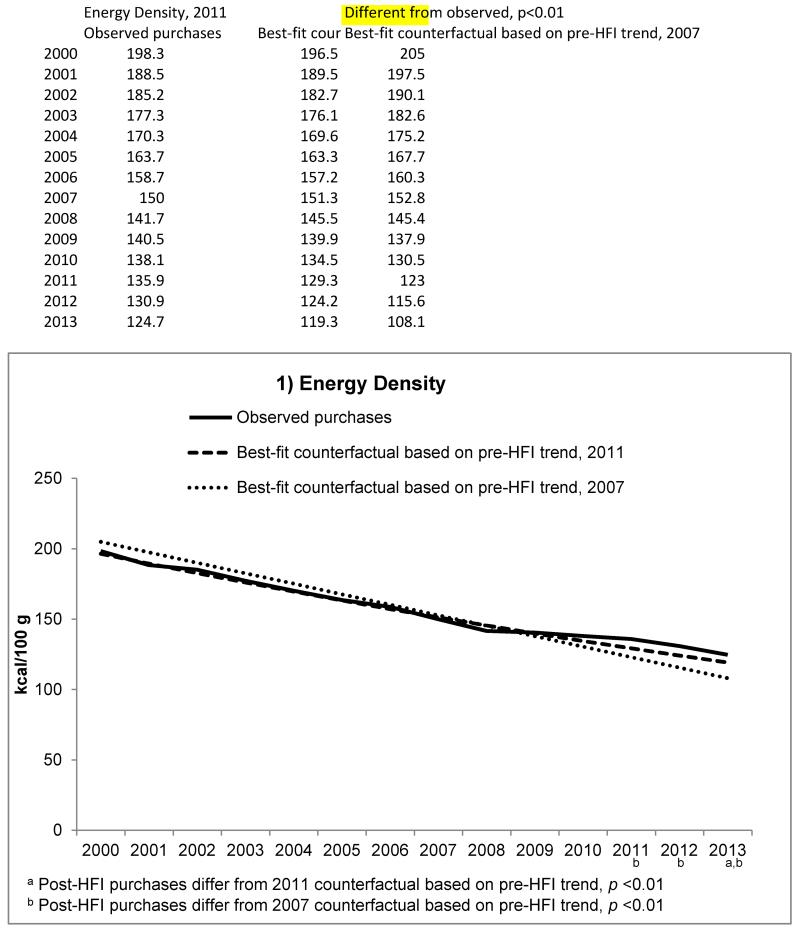

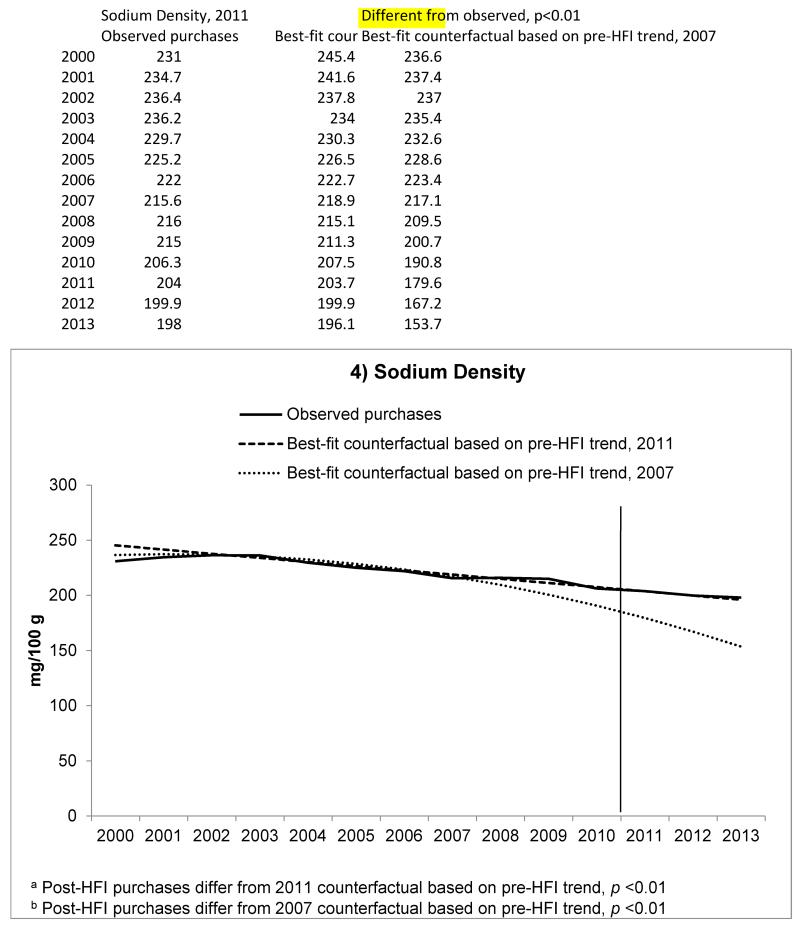

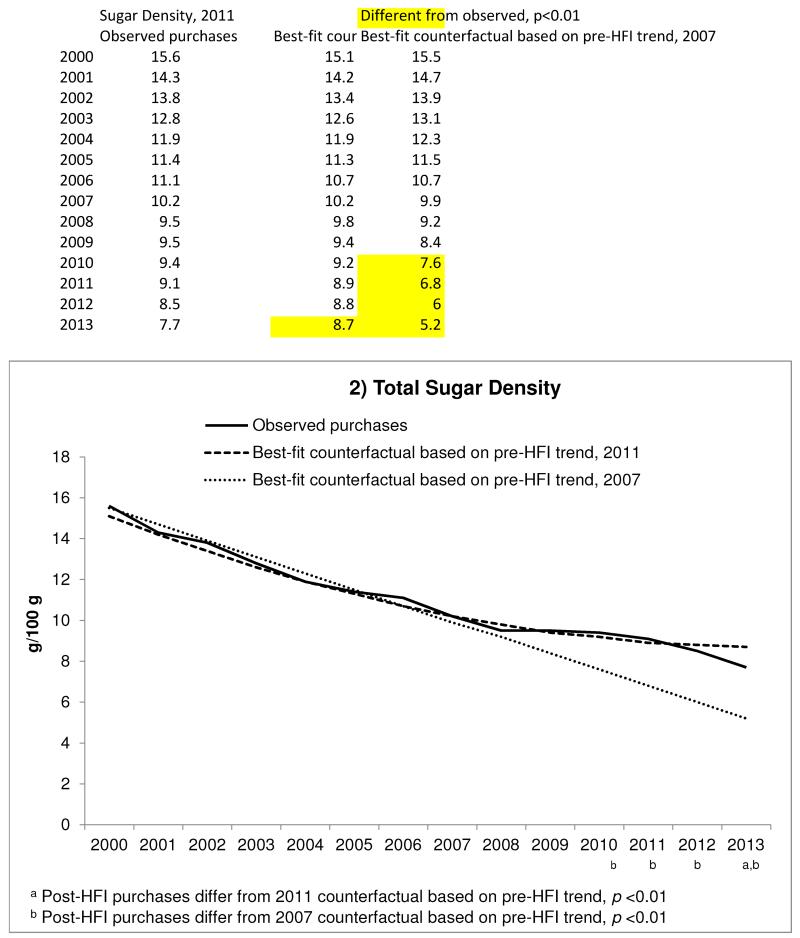

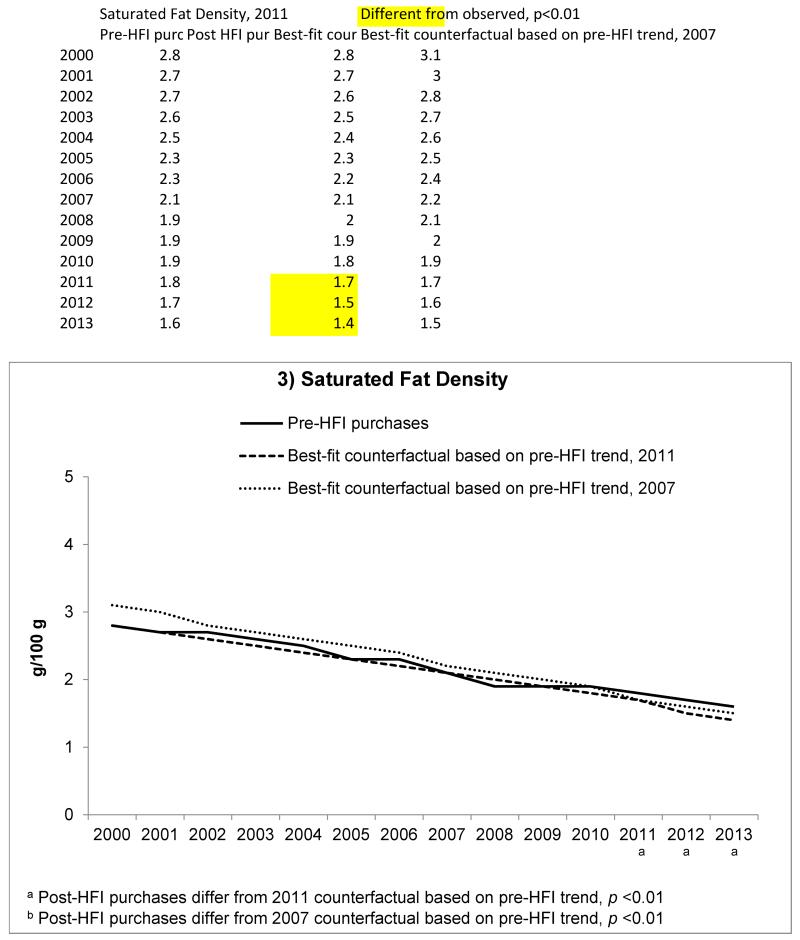

Figures comparing the observed nutrient density of Walmart PFPs pre- and post-HFI to the best-fit counterfactuals based on pre-HFI trends for a 2011 vs. 2007 HFI are shown in Exhibits 1 to 4. Walmart PFPs showed a 74 kcal/100g decline in energy density from 2000 to 2013, although this decline leveled off around the late 2000s. In fact, after the 2011 HFI, Walmart PFPs declined less in energy density than what would be expected based on the pre-2011-HFI trend (p<0.01 in 2013) (Exhibit 1). While the rate of decline for total sugar density of Walmart PFPs also slowed around 2007, the total sugar density of PFPs during the post-2011-HFI period was very similar to what we would expect based on pre-2011-HFI trends, and in 2013, the total sugar density of Walmart PFPs was less than what we would expect based on pre-2011-HFI trends (p<0.01) (Exhibit 2). The saturated fat density of Walmart PFPs showed small declines from 2000 to 2013, but again, the saturated fat density of PFPs during the post-2011-HFI period was slightly but significantly higher than expected based on the pre-HFI trend (p <0.01) (Exhibit 3). Sodium density decreased by 33 mg/100g from 2000 to 2013, but post-2011-HFI sodium density was virtually identical to the sodium density we would have expected based on pre-HFI trends (Exhibit 4).

Exhibit 1. Observed vs. counterfactual energy density of Walmart packaged food purchases pre- and post-HFI.

Source: Authors’ analysis of Nielsen Homescan data, 2000-2013

Exhibit 4. Observed vs. counterfactual sodium density of Walmart packaged food purchases pre- and post-HFI.

Source: Authors’ analysis of Nielsen Homescan data, 2000-2013

Exhibit 2. Observed vs. counterfactual total sugar density of Walmart packaged food purchases pre- and post-HFI.

Source: Authors’ analysis of Nielsen Homescan data, 2000-2013

Exhibit 3. Observed vs. counterfactual saturated fat density of Walmart packaged food purchases pre- and post-HFI.

Source: Authors’ analysis of Nielsen Homescan data, 2000-2013

Using 2007 as the HFI cut-point tended to amplify the results for Walmart PFPs, and in some cases reversed them, with the general effect being that observed post-2007 HFI nutrient densities were even higher than what would be expected based on the pre-2007 trend. For example, the disparity between the observed decline in energy density of Walmart PFPs and what we would have expected based on pre-HFI trends widened (Exhibit 1). Using the 2007 HFI start date reversed the result for total sugar density, with post-HFI total sugar density substantially higher than what would be expected based on pre-2007 trends (p <0.01) (Exhibit 2).

Appendix Exhibit 322 shows the percent volume purchased from key food groups at Walmart. Overall, the percent volume of SSBs from Walmart declined only slightly, although this decline was more than expected based on pre-2011-HFI trend (p <0.01). Percent volume of fruits and vegetables increased only slightly, and increases during the post-HFI period were the same as expected. Percent volume of grain-based desserts, savory snacks, and candy from Walmart also declined, although the post-HFI declines were no different than expected from pre-HFI trends.

Similar results were found when we examined shifts in percent volume of food groups using the 2007 start date, with a reversal or widening of the gap so that post-HFI percent volumes declined less than expected. For example, using the 2007 start-date, we find that there was no difference between the percent volume of SSBs purchased from Walmart post-HFI and what would have been expected based on pre-HFI trends.

When we looked at other chain retailers, we found that PFPs from other chain retailers showed similar but smaller trends in nutrient densities and percent volume from key food groups (Appendix Exhibits 4 and 5)22. For energy, total sugar, and sodium densities, post-HFI declines were larger than expected based on pre-HFI trends (p<0.01), although the overall declines were minimal (11 kcal/100g, less than 2 g/100g, and 20 mg/100g, respectively).

DISCUSSION

From 2000 to 2013, energy, total sugar, and sodium densities of PFPs from Walmart declined substantially, and these changes were greater than those observed in PFPs from other chain food retailers. On the whole, however, using 2011 as the date for which the HFI was enacted, we find that in general, post-HFI shifts in nutrient density and percent volume of key food groups were similar to or less than what we would expect had pre-HFI trends simply continued. These results are contrary to what we would expect if the HFI truly marked a turning point in how Walmart formulates, prices, and markets its foods: if anything, we would expect nutrient densities of Walmart PFPs to have declined more quickly after the HFI was enacted.

Instead, we see that the declines in nutrient density and shifts in percent volume from key food groups were steepest in the early 2000’s, and leveled off around 2007/2008. In fact, these results mirror the Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation evaluation, which found that post-pledge declines in caloric purchases were smaller than expected based on the pre-pledge trend.16 In the current example, declines in the earlier 2000’s followed by a leveling off around 2007 could simply reflect Walmart’s continued expansion of its grocery lines within supercenters, as well as increased consumer perception of Walmart as a place to shop for groceries, not just the occasional sweet or soda. By the end of the observation period, purchases at Walmart simply resemble those at other chain retailers, suggesting that its improvements brought it up to par with other retailers rather than representing an improvement beyond current industry standards.

One notable exception was the shift in percent volume of SSBs purchased from Walmart. Although the total decline in SSBs was only 1 percent from 2000 to 2013, this decline was more than we would have expected given pre-HFI trends, which indicated that SSB purchases were actually increasing prior to the 2011 HFI. Given that Walmart has not publically indicated whether their HFI has targeted SSB purchases, it is unclear whether this shift in SSB purchases was truly the result of the HFI. Possibly these changes simply reflect a shift in the public attitudes towards SSBs as a result of public health campaigns about the potential health consequences of SSBs-- although such a shift in awareness would have likely resulted in a downwards shift in SSB purchases at other chain retailers; as well, which we did not see. In general, the SSB trends Walmart and other chain retailers contradict to recent findings showing that caloric purchases from SSBs have decreased over recent years.30 Since our results focused on only on volume purchased, the lack of decline in SSB volume purchased could indicate that consumers are not decreasing the total volume of SSBs purchased, but simply shifting to less energy dense purchases as more beverages with lower-calorie sweeteners are introduced.31

The lack of post-HFI changes begs the question: was Walmart’s HFI simply a marketing scheme designed to improve public image and get ahead of mounting pressure from public health advocates to improve the nutritional quality of food?32 On the other hand, the observed lack of post-HFI changes may be attributable to our inability to separately examine Walmart’s store-brand products, although we would expect that if these changes in store-brand products had been large enough, they would have been reflected in our analysis of overall purchases.

This work also shows that the choice of baseline period matters for determining whether HFIs are responsible for observed changes in nutritional profile. When we use a 2007 start-date for the HFI, we find that declines in the nutrient densities of Walmart PFPs are markedly less than we would have expected. This likely occurred because for the energy-containing nutrients, the majority of declines occurred prior to 2007, and then leveled off. Thus, when 2011 is used as the start-date, the quadratic trend fits best and creates a post-HFI trajectory that is very similar to what was actually observed for energy, total sugar, and saturated fat densities. However, a 2007 start dates yields us a linear post-HFI trajectory, and since these declines were occurring at a relatively steeper rate prior to 2007, when we look to see what happened after 2007, the post-HFI nutrient densities declined significantly less than we would have expected had the pre-HFI trend continued. Future evaluations, especially those relying on natural experiments where the implementation date is not always clear, should consider how results change when different baseline periods are used.

It was also surprising that although the energy density, total sugar, and sodium density of PFPs from other chain retailers declined more rapidly than expected during the post-HFI period, overall declines were minimal. Even though the time trend was based on Walmart’s HFI, we would have expected to see larger declines, especially after 2007 and 2011, in part because of Walmart’s influence. Because of its size, Walmart’s price cuts or negotiations with suppliers to reformulate products could have ed to lower prices on produce or the introduction of healthier options at other chain retailers as well.33-35 Additionally, we might have expected to see steeper declines in later years due the implementation of HFIs at other major retailers, including Safeway, Kroger, and Delhaize,36-38 although the geographic scope of these HFIs is currently unclear.

Conclusion

From 2000 to 2013, the largest food retailer in the US, Walmart, showed major declines in energy, total sugar, and sodium density of PFPs, above and beyond concurrent trends in comparable food retailers. However, the majority of these changes occurred prior to the official implementation of its HFI, indicating that the HFI was not responsible for these improvements. Limitations, including the inability to explicitly examine Walmart store-brand products, warrant further research into Walmart’s HFI as well as other food retailer-based initiatives. However, the current results suggest that retailer-based initiatives may not result in meaningful changes in the nutritional profile of what people buy. In fact, these results are comparable to recent work from the food access literature, which show that placing food retailers in an areas of low access is not enough to improve healthfulness of food purchases.13, 39, 40 It seems as though simply changing the food retail environment is not enough. In fact, a recent study concluded that educational differences, not introduction of new stores or changes in store offerings, were the major driver of disparities in the nutritional quality of food purchases.40 Thus, while food retailers should be engaged in efforts to create a healthier food environment, more systemic shifts in the underlying characteristics and preferences of the population may be needed to meaningfully improve the healthfulness of food purchases.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Glanz K, Bader MD, Iyer S. Retail grocery store marketing strategies and obesity: an integrative review. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(5):503–12. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cummins S, Petticrew M, Higgins C, Findlay A, Sparks L. Large scale food retailing as an intervention for diet and health: quasi-experimental evaluation of a natural experiment. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(12):1035–40. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.029843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poti JM, Popkin BM. Trends in energy intake among US children by eating location and food source, 1977-2006. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(8):1156–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith LP, Ng SW, Popkin BM. Trends in US home food preparation and consumption: analysis of national nutrition surveys and time use studies from 1965–1966 to 2007–2008. Nutr J. 2013;12(1):45. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-12-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wood S. Revisiting the US food retail consolidation wave: regulation, market power and spatial outcomes. Econ Geog. 2013:lbs047. [Google Scholar]

- 6.United States Department of Agriculture ERS Retail Trends. 2014 [cited 2014 April]. Available from: http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-markets-prices/retailing-wholesaling/retail-trends.aspx#.U0uybPldWSq.

- 7.Banjo S, Gasparro A. Retailers Brace for Reduction in Food Stamps. Wall Street Journal [Internet] 2013 2014 May; Available from: http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702303843104579168011245171266. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wal-mart Stores Inc. Walmart Launches Major Initiative to Make Food Healthier and Healthier Food More Affordable. Washington, D.C.: 2011. [cited 2013 July ]. Available from: http://news.walmart.com/news-archive/2011/01/20/walmart-launches-major-initiative-to-make-food-healthier-healthier-food-more-affordable. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wal-Mart Stores Inc. Making healthier food a reality for all. 2013 [cited 2013 October]. Available from: http://corporate.walmart.com/global-responsibility/hunger-nutrition/our-commitments.

- 10.Sutherland LA, Kaley LA, Fischer L. Guiding stars: the effect of a nutrition navigation program on consumer purchases at the supermarket. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(4):1090S–4S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.28450C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brinkman H-J, de Pee S, Sanogo I, Subran L, Bloem MW. High food prices and the global financial crisis have reduced access to nutritious food and worsened nutritional status and health. J Nutr. 2010;140(1):153S–61S. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.110767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beatty TK, Senauer B. The New Normal? U.S. Food Expenditure Patterns and the Changing Structure of Food Retailing. Am J Agric Econ. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cummins S, Flint E, Matthews SA. New Neighborhood Grocery Store Increased Awareness Of Food Access But Did Not Alter Dietary Habits Or Obesity. Health Aff. 2014;33(2):283–91. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wrigley N, Warm D, Margetts B. Deprivation, diet, and food-retail access: findings from the Leedsfood deserts’ study. Environ Plann A. 2003;35(1):151–88. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foster GD, Karpyn A, Wojtanowski AC, Davis E, Weiss S, Brensinger C, et al. Placement and promotion strategies to increase sales of healthier products in supermarkets in low-income, ethnically diverse neighborhoods: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(6):1359–68. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.075572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ng SW, Popkin BM. The Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation Marketplace Commitment and Consumer Packaged Goods purchased by US households with children. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(4):520–30. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohri-Vachaspati P, Turner L, Chaloupka FJ. Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program participation in elementary schools in the United States and availability of fruits and vegetables in school lunch meals. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(6):921–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bassett MT, Dumanovsky T, Huang C, Silver LD, Young C, Nonas C, et al. Purchasing behavior and calorie information at fast-food chains in New York City, 2007. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(8):1457–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.135020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ng SW, Slining MM, Popkin BM. The healthy weight commitment foundation pledge: calories sold from U.S. Consumer packaged goods, 2007-2012. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(4):508–19. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhen C, Taylor JL, Muth MK, Leibtag E. Understanding differences in self-reported expenditures between household scanner data and diary survey data: a comparison of Homescan and consumer expenditure survey. Appl Econ Perspect Pol. 2009;31(3):470–92. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slining MM, Ng SW, Popkin BM. Food companies’ calorie-reduction pledges to improve U.S. diet. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(2):174–84. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.09.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.To access the Appendix click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online.

- 23.Hogan JW, Lancaster T. Instrumental variables and inverse probability weighting for causal inference from longitudinal observational studies. Stat Methods Med Res. 2004;13(1):17–48. doi: 10.1191/0962280204sm351ra. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akin JS, Guilkey DK, Popkin BM. The school lunch program and nutrient intake: A switching regression analysis. Am J Agric Econ. 1983;65(3):477–85. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dötsch M, Busch J, Batenburg M, Liem G, Tareilus E, Mueller R, et al. Strategies to reduce sodium consumption: a food industry perspective. Crc Cr Rev Food Sci. 2009;49(10):841–51. doi: 10.1080/10408390903044297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bureau of Labor Statistics Local area unemployment statistics. [cited June 2014]. Available from: http://www.bls.gov/lau/

- 27.Holmes TJ. Opening dates of Wal-Mart stores and Supercenters. 2010 1962-Jan 31,2006. [cited June 2014]. Available from: http://www.econ.umn.edu/~holmes/data/WalMart/store_openings.html.

- 28.AggData Complete list of all Walmart store locations in the USA. 2014 [cited June 2014]. Available from: http://www.aggdata.com/aggdata/complete-list-walmart-locations.

- 29.Walmart Inc. Sustainable Agriculture. 2014 [cited April 2014]. Available from: http://corporate.walmart.com/global-responsibility/environment-sustainability/sustainable-agriculture.

- 30.Kit BK, Fakhouri TH, Park S, Nielsen SJ, Ogden CL. Trends in sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among youth and adults in the United States: 1999-2010. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(1):180–8. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.057943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piernas C, Ng S, Popkin B. Trends in purchases and intake of foods and beverages containing caloric and low-calorie sweeteners over the last decade in the United States. Pediatr Obes. 2013 doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2013.00153.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mozaffarian D. The Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation Trillion Calorie Pledge: Lessons from a Marketing Ploy? Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(4):e9–e10. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Volpe RJ, Lavoie N. The effect of Wal-Mart supercenters on grocery prices in New England. Appl Econ Perspect Pol. 2008;30(1):4–26. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leibtag ES, Barker C, Dutko P. How much lower are prices at discount stores? An examination of retail food prices. United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Basker E, Noel M. The Evolving Food Chain: Competitive Effects of Wal-Mart’s Entry into the Supermarket Industry. J Econ Manag Strategy. 2009;18(4):977–1009. [Google Scholar]

- 36.BusinessWire Safeway Announces ‘SimpleNutrition’, an In-Store Shelf Tag System, to Help Shoppers Findthe Right Nutrition Choices for Them. 2011 [cited 2014]. Available from: http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20110215007790/en/Safeway-Announces-%E2%80%98SimpleNutrition%E2%80%99-In-Store-Shelf-Tag-System#.VD57YvldWSo.

- 37.Food Lion Guiding Stars. 2014 [cited 2014 October]. Available from: http://www.foodlion.com/NutritionWellBeing/Nutrition/GuidingStars.

- 38.Kroger Health Matters. 2014 [cited 2014]. Available from: https://www.kroger.com/topic/health-matters-3.

- 39.Elbel B, Moran A, Dixon LB, Kiszko K, Cantor J, Abrams C, et al. Assessment of a government-subsidized supermarket in a high-need area on household food availability and children’s dietary intakes. Public Health Nutr. 2015:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S1368980015000282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Handbury J, Rahkovsky I, Schnell M. What drives nutritional disparities? Retail access and food purchases across the socioeconomic spectrum. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2015. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.