Abstract

Argonaute proteins are key components of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). They provide both architectural and catalytic functionalities associated with small interfering RNA (siRNA) guide strand recognition and subsequent guide strand-mediated cleavage of complementary mRNAs. We report on the 3.0 Å crystal structures of 22-mer and 26-mer siRNAs bound to Aquifex aeolicus Argonaute (Aa-Ago), where one 2 nt 3′ overhang of the siRNA inserts into a cavity positioned on the outer surface of the PAZ-containing lobe of the bilobal Aa-Ago architecture. The first overhang nucleotide stacks over a tyrosine ring, while the second overhang nucleotide, together with the intervening sugar-phosphate backbone, inserts into a preformed surface cavity. Photochemical crosslinking studies on Aa-Ago with 5-iodoU-labeled single-stranded siRNA and siRNA duplex provide support for this externally bound siRNA-Aa-Ago complex. The structure and biochemical data together provide insights into a protein-RNA recognition event potentially associated with the RISC-loading pathway.

Introduction

The Argonaute (Ago) protein is a key component of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), where it mediates small interfering RNA (siRNA) guide strand recognition, followed by guide strand-mediated cleavage of complementary mRNAs (reviewed in Sontheimer, 2005; Tomari and Zamore, 2005; Kim, 2005; Filipowicz et al., 2005; Lingel and Sattler, 2005; Filipowicz, 2005; Tanaka Hall, 2005). Recent crystal structures of archaeal P. furiosus Ago (Pf-Ago) (Song et al., 2004) and eubacterial A. aeolicus Ago (Aa-Ago) (Yuan et al., 2005) have established an overall bilobal architecture for these proteins in the free state, consisting of PAZ-containing (N and PAZ domains and L1 and L2 linkers) and PIWI-containing (L2 linker and Mid and PIWI domains) lobes. To date, no structures have been reported for any RNA-Ago complex, though structures are available for the PAZ domain bound to a mini-siRNA (Ma et al., 2004) and single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) (Lingel et al., 2004) and for the A. fulgidus Piwi protein (composed of Mid and PIWI domains) (Parker et al., 2004) bound to siRNA (Parker et al., 2005; Ma et al., 2005).

Here, we report on crystal structures of Aa-Ago bound to 22-mer and 26-mer self-complementary siRNAs, and we have unexpectedly identified an externally bound siRNA-Ago complex. The 2 nt 3′ overhang at one end of the siRNA inserts into a cavity positioned on the outer surface of the PAZ-containing lobe of the bilobal Aa-Ago architecture in both complexes. Support for this architecture comes from photochemical crosslinking studies on complexes of 5-iodouridine (5-iodoU)-labeled ssRNA and siRNA, with both wild-type and mutant Aa-Ago. The externally bound siRNA-Aa-Ago complex potentially provides insights into siRNA duplex recognition by Ago along the RISC-loading pathway, prior to uptake of single-stranded guide siRNA inside of the bilobal scaffold of Ago, which, in turn, leads to guide strand-mediated cleavage of complementary mRNAs by catalytically competent RISC.

Results

Crystallization and Structure Determination

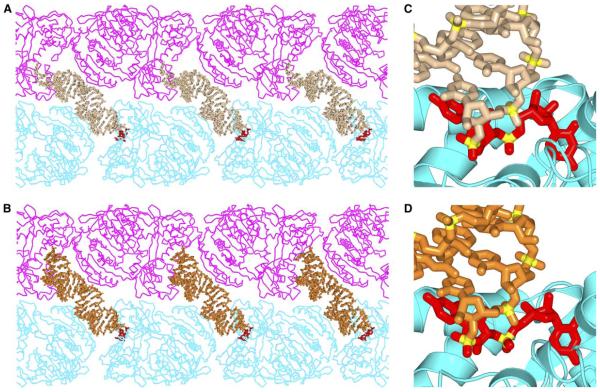

We have grown crystals of Aa-Ago bound to self-complementary 22-mer and 26-mer siRNAs, which diffract to 3.0 Å and 3.1 Å resolution, respectively. Both crystals belong to the P21 space group, and the structures were solved by molecular replacement; the structure of the free Aa-Ago solved previously in our laboratory (Yuan et al., 2005) was used as a search model. Crystallographic data and refinement statistics are listed in Table 1, and the packing arrangements for the 22-mer siRNA-Ago complex and the 26-mer siRNA-Ago complex are shown in Figure 1A and Figure 1B, respectively. The asymmetric unit contains two copies of Aa-Ago (Cα backbone traces are colored magenta and cyan, Figures 1A and 1B) and one siRNA duplex (stick representation, Figure 1) for both complexes.

Table 1.

Crystallographic Data Collection, Statistics, and Analysis

| 22 nt Bound Aa-Ago |

26 nt Bound Aa-Ago |

|

|---|---|---|

| Crystallographic Data, Space Group P2(1) |

||

|

| ||

| Unit cell dimensions | ||

| a (Å) | 81.10 | 81.20 |

| b (Å) | 118.23 | 118.08 |

| c (Å) | 99.13 | 98.50 |

| β (°) | 99.43 | 99.57 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.1 | 1.54 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50~3.0 | 50~3.1 |

| Redundancy (last shell) | 6.9 (6.7) | 7.6 (7.2) |

| Unique observations | 36,781 | 33,373 |

| Completeness (%) (last shell) |

99.4 (99.8) | 100.0 (99.9) |

| I/σ(I) (last shell) | 26.4 (5.8) | 24.4 (8.9) |

| Rsym (%) (last shell)a | 6.6 (37.1) | 8.7 (43.2) |

|

| ||

| Refinement | ||

|

| ||

| Resolution range (Å) | 50~3.0 | 50~3.1 |

| Rfactor (Rfree) (%)b,c | 21.1 (29.6) | 20.4 (29.7) |

| Rms bond length deviations (Å) |

0.015 | 0.016 |

| Rms angles deviations (°) |

1.663 | 1.722 |

| Average B values (Å2 ) | ||

| Protein | 72.7 | 55.9 |

| RNA | 86.0 | 59.1 |

| Water | 52.9 | 34.9 |

| % core (allowed) in Ramachandran plot |

85.6 (13.1) | 84.2 (14.5) |

Rsym is the unweighted R value on I between symmetry mates. The last shell has a resolution between 3.11 Å and 3.0 Å for 22 nt bound Aa-Ago and 3.21 Å and 3.1 Å for 26 nt bound Aa-Ago.

R factor = Σhkl∥Fo(hkl)| – |Fc(hkl)∥Σhkl|Fo(hkl)|.

Rfree is the crossvalidation R factor for 5% of reflections against which the model was not refined.

Figure 1. Packing Arrangements and Common Intermolecular Interactions in the Crystal Structures of siRNA-Bound Aa-Ago Complexes.

(A) Crystallographic packing in the complex between 22-mer siRNA and Aa-Ago. The asymmetric unit contains one siRNA and two Aa-Ago molecules, one colored cyan and the other colored magenta. Crystallographically related Aa-Agos are shown with the same color, and the 22-mer siRNA duplex is colored beige, except for the 2 nt overhang at one end (colored red), which interacts with the protein in a specific manner.

(B) Crystallographic packing in the complex between 26-mer siRNA and Aa-Ago. The 26-mer siRNA duplex is colored orange, except for the 2 nt overhang at one end, which is colored red.

(C) The specific interactions between the 2 nt overhang of siRNA and the PAZ-containing lobe of Aa-Ago in the 22-mer siRNA-bound Aa-Ago complex associated with (A).

(D) The corresponding specific interactions in the 26-mer siRNA-bound Aa-Ago complex associated with (B).

Crystal Packing

There are two sets of protein-RNA interactions within the packing arrangement of the 22-mer siRNA-Ago (Figure 1A) and 26-mer siRNA-Ago (Figure 1B) complexes. One of these involves the 2 nt 3′ overhangs of the siRNA duplex, which are directed toward the outward-facing surface of the PAZ-containing lobe, while the other involves alignment of the siRNA duplex segment opposite the Mid domain of the PIWI-containing lobe.

Specific Interaction with One siRNA 3′-Overhang End

One siRNA duplex 2 nt 3′-overhang end (indicated in red in Figures 1A and 1B) exhibits the same extended conformation (Figures 1C and 1D) and inserts into the same cavity (Figures 1C and 1D) on the outward-facing surface of the PAZ-containing lobe of the cyan-colored Aa-Ago in both the 22-mer (Figures 1A and 1C) and the 26-mer (Figures 1B and 1D) complexes. By contrast, the 2 nt 3′ overhang at the opposite end of the siRNA duplex makes different contacts with the outward-facing surface of the PAZ-containing lobe of the magentacolored Aa-Ago in the 22-mer (Figure 1A) and 26-mer (Figure 1B) complexes, neither of which involve specific recognition.

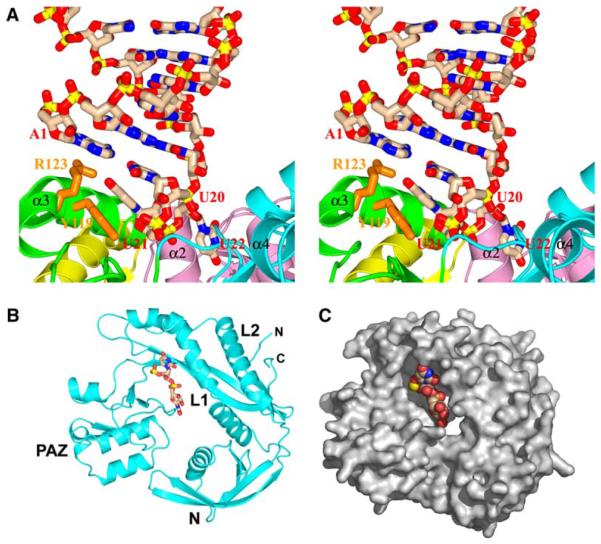

The detailed intermolecular interactions associated with the specific sequestration of the 2 nt overhang segment at one end in the 22-mer siRNA-Ago complex is shown in stereo in Figure 2A. The U21 and U22 bases of the 2 nt overhang adopt a splayed-apart conformation (Figures 1C and 2A). The terminal A1•U20 pair is precisely positioned above the cavity by stacking of A1 with the hydrophobic methylene side chain of R123 and continued stacking of U20 with U21, the first overhang base. U21, in turn, is anchored by being sandwiched between U20 and the aromatic ring of Y119. U22, the second overhang base, inserts into the cavity, which also sequesters the sugar-phosphate backbone associated with the U20-U21 and U21-U22 steps (Figures 2A–2C).

Figure 2. Detailed Views of Specific Protein-RNA Interactions in the Complex between 22-mer siRNA and Aa-Ago.

(A) A stereoview of interactions between the 2 nt overhang at one end of the externally bound 22-mer siRNA and the outer surface of the PAZ-containing lobe (pink-colored N and cyan-colored PAZ domains; green-colored L1 and yellow-colored L2 linkers) of Aa-Ago (cyan-colored in Figure 1A). The overhang base U21 stacks on the aromatic ring of orange-colored Y119, which is highly conserved among bacterial Agos, while the overhang base U22 is inserted into a cavity whose walls involve segments from α2 of the N domain, α3 from the L1 linker, and loops from the PAZ domain. Further, A1 and U20 of the terminal A1•U20 base pair stack on the side chain of orange-colored R123 and the U21 base, respectively.

(B) Ribbon representation of the outward-pointing face of the PAZ-containing lobe of the cyan-colored Aa-Ago (Figure 1A); the bound 2 nt 3′ overhang is shown in a stick representation. The color coding of domains and linkers is as in (A). The bound 2 nt overhang segment is shown in a stick representation.

(C) Surface representation of the PAZ-containing lobe as in (B); the bound 2 nt overhang segment is shown in space-filling representation. interaction between Dicer and the Piwi box of Ago may also play a role during small RNA loading.

Nonspecific Interactions with the siRNA Duplex Segment

The alignment of the siRNA duplex segment opposite the Mid domain of the PIWI-containing lobe in the 22-mer siRNA-Aa-Ago complex is outlined in Figure S1 (see the Supplemental Data available with this article online). We do not observe any direct intermolecular contacts, and the amino acids that project from the Mid interface toward the siRNA are not conserved among Ago sequences. We conclude that such interactions are not likely to be functionally relevant and appear to be restricted to crystal-packing contributions.

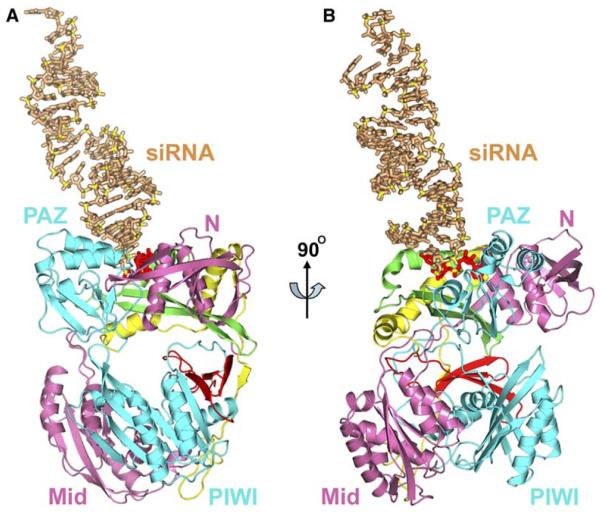

Structure of the Aa-Ago Complex with Externally Bound 22-mer siRNA

We focus our structural analysis on the specific recognition of one 3′-overhang end of the siRNA duplex, which is bound by the cyan-colored Aa-Ago (two alternate views of this 22-mer siRNA-Ago complex are shown in Figures 3A and 3B). Molecular recognition is restricted to the 2 nt overhang of the siRNA duplex; hence, it is not surprising that the structures of free (Yuan et al., 2005) and bound Aa-Ago are similar, with an rmsd of 2.1 Å (for 682 backbone Cα atoms).

Figure 3. Crystal Structure of the Complex between 22-mer siRNA and Aa-Ago.

(A) A view of the crystal structure of the complex between externally bound 22-mer siRNA and Aa-Ago. The color codes of the various domains and linkers of Aa-Ago are as follows: N domain, pink; L1 linker, green; PAZ domain, cyan; L2 linker, yellow; Mid domain, pink; PIWI domain, cyan; and PIWI box, red. The siRNA is shown in beige, except for the 2 nt overhang at one end, which is colored red. The backbone phosphorus atoms are colored yellow.

(B) The view in (A) rotated by 90° along the z axis.

The siRNA duplex is bound to the outer surface of the PAZ-containing lobe of the bilobal Aa-Ago architecture (Figure 2B), through positioning of the overhang segment in a cavity (Figure 2C), whose walls are lined by residues projecting from two α helices (α1 and α2) of the N domain, one α-helix (α3) and one β strand (β8) from the L1 linker and loop segments (inking β9-α4 and β10-β11) from the PAZ domain, and whose base is formed by the loop (linking β14 and α8) segment between the PAZ domain and L2 linker (Figure 2B). This cavity is preformed and buries the 2 nt overhang segme t as shown in Figure 2C.

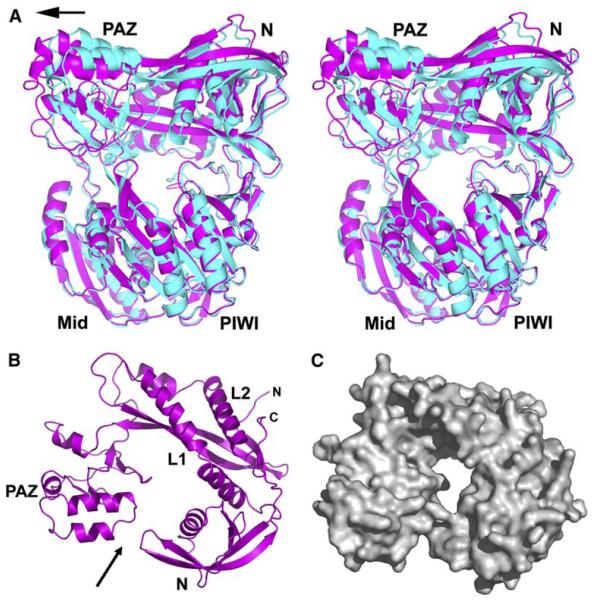

Variability in the PAZ Domain-N Domain Separation

There are two distinct Aa-Ago molecules (colored cyan and magenta, Figure 1A) in the asymmetric unit of the 22-mer siRNA-Aa-Ago complex. Their PIWI-containing lobes can be superpositioned with an rmsd of 1.3 Å (for 397 Ca atoms) (Figure 4A). The principal difference between the two Aa-Ago folds is restricted to the alignment of the PAZ domain, which shifts further from the N domain as one proceeds from the cyan-colored Aa-Ago to the magenta-colored Aa-Ago (Figure 4A). This relative shift of PAZ relative to N can also be alternately visualized after comparison of the PAZ-containing lobes of the cyan-colored Aa-Ago with the bound 2 nt overhang (Figures 2B and 2C) with those of the magenta-colored Aa-Ago (Figures 4B and 4C).

Figure 4. Superpositioning of the Two Aa-Ago Molecules in the Asymmetric Unit in the Complex.

(A) A stereoview of the superpositioning of two Aa-Ago molecules (colored cyan and magenta according to the color scheme in Figure 1A) in the asymmetric unit of the complex. The molecules were superpositioned relative to their PIWI-containing lobes. Note that the major difference between the two Aa-Ago molecules is restricted to the relative positioning of their PAZ domains (shown by arrow).

(B) Ribbon representation of the outward-pointing face of the PAZ-containing lobe of the magenta-colored Aa-Ago (Figure 1A). Compare with the corresponding view of the cyan-containing Aa-Ago shown in Figure 2B. The increased separation between N and PAZ domains observed in (B) relative to Figure 2B is indicated by an arrow.

(C) Surface representation of the PAZ-containing lobe as in (B). Compare with the corresponding view of the cyan-containing Aa-Ago in Figure 2C.

Photoreactive Crosslinking

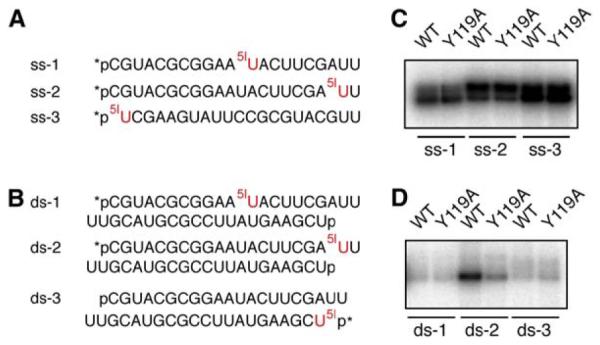

The first 3′ overhang base, U21 of the 22-mer siRNA duplex, stacks with the aromatic ring of Y119 of Aa-Ago in the crystal structure of the siRNA-Ago complex (Figure 2A). We have performed a photoactivated crosslinking assay, by using RNAs containing site specifically modified 5-iodoU and either wild-type or Y119A mutant Aa-Ago protein, to examine whether this specific interaction observed in the crystal also exists in solution.

The Y119A mutant protein was purified to comparable homogeneity to the wild-type Aa-Ago (Figure S2A). The mutant is functionally indistinguishable from wild-type Aa-Ago with regard to either ssDNA- or ssRNA-guided target RNA cleavage activity (Figure S2B and data not shown). The RNAs used for crosslinking are either 21 nt single-stranded siRNA (Figure 5A) or siRNA duplexes (Figure 5B). Each of them was 5′ 32P radiolabeled and contains a 5-iodoU either in the middle (ss-1 and ds-1), at the first overhang nucleotide at the 3′ end (ss-2 and ds-2), or at the 5′ end (ss-3 and ds-3) of the radiolabeled strand (Figures 5A and 5B).

Figure 5. Crosslinking of Wild-Type and Mutated Y119A Aa-Agos to Single-Stranded, ss, or Double-Stranded, ds, siRNAs Containing 5-IodoU.

(A and B) (A) Sequences of the 5-iodoU (5IU)-containing ssRNAs. (B) Sequences of the 5-iodoU (5IU)-containing siRNA duplexes. The 5′ end of each RNA strand was phosphorylated, either via chemical synthesis (p) or 32P-labeling (*p).

(C and D) (C) Patterns of Aa-Ago proteins crosslinked to ssRNAs containing 5-iodoU. (D) Patterns of Aa-Ago proteins crosslinked to siRNA duplexes containing 5-iodoU. Wild-type Aa-Ago and Y119A mutant were incubated with 5-iodoU-modified ssRNAs or siRNA duplexes, irradiated with 312 nm UV light for 8 min, and analyzed on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel. The crosslinked products were revealed by phosphorimaging.

We found that single-stranded 21-mer siRNAs crosslinked more efficiently (Figure 5C) than the corresponding siRNA duplexes (Figure 5D). Among the single-stranded siRNAs, ss-3, which possesses a 5-iodoU at the first 5′ base, gave rise to the strongest crosslinking (Figure 5C).

More importantly, there was a distinct crosslinked product of wild-type Aa-Ago with ds-2, the siRNA duplex containing the 5-iodoU at the penultimate overhang base (Figure 5D). Substitution of Y119 of Aa-Ago with alanine significantly decreased the efficiency of crosslinking by about 3-fold (Figure 5D), and this value persisted at various time points examined (Figure S3), suggesting that the Tyr at this position is indeed important for the recognition of the 3′ overhang of the siRNA duplex. The other two siRNA duplexes, ds-1 and ds-3, containing 5-iodoU in the middle or the 5′ end of the radiolabeled strand, respectively, had weak or almost no cross-linking with Aa-Ago, and there was also no appreciable difference between wild-type and mutant Y119 Aa-Agos (Figure 5D).

Discussion

The RISC-Loading Pathway

There have been significant advances over the last 2 years in our current understanding of the assembly steps leading to the generation of a catalytically competent RISC (reviewed in Sontheimer, 2005; Tomari and Zamore, 2005; Filipowicz, 2005). A key intermediate in the RISC-assembly pathway is the RISC-loading complex (RLC), which in Drosophila is composed of the Dicer protein Dcr-2 and the dsRNA binding protein R2D2, bound to opposite ends of the siRNA duplex (Pham et al., 2004; Tomari et al., 2004a). The Dcr-2/R2D2 heterodimer binds the siRNA duplex in an asymmetric manner, with R2D2 and Dcr-2 targeted to the more and less stable ends of the siRNA duplex, respectively, thereby defining the directionality of small RNA loading onto RISC. It is conceivable that the siRNA duplex is transferred to Ago through initial external binding followed by internalization within the basic channel between opposing PAZ-containing and PIWI-containing lobes of the bilobal Ago architecture. Therefore, the orientation of siRNA duplex binding predefines the guide strand, and Ago probably facilitates the transition or docking of the siRNA duplex. Furthermore, the

The challenge from a molecular perspective is to determine structures of Ago complexes with both externally bound and internally bound siRNAs, including complexes with internally bound single-stranded guide siRNA and guide strand-mRNA duplexes. The externally bound siRNA-Ago complexes could shed light on potential recognition events along the RISC-loading pathway, while internally bound complexes could shed light on recognition events in the catalytically competent RISC complex.

Structure of the Externally Bound siRNA-Ago Complex

Since the crystal structure determination of the Pf-Ago (Song et al., 2004) and Aa-Ago (Yuan et al., 2005) in the free state, much effort has been directed toward the structure determination of siRNA-Ago complexes. To date, no structures have been reported for complexes in which the single-stranded guide siRNA or guide strand-mRNA duplex is positioned internally between the PAZ-containing and PIWI-containing lobes of the bilobal Aa-Ago architecture. Rather, available insights into molecular recognition are restricted to models of such complexes (see Song et al., 2004; Yuan et al., 2005; Tanaka Hall, 2005).

On the other hand, several lines of evidence suggest that it could be difficult to grow crystals of Ago proteins internally bound to siRNA in the absence of other components of the RLC: (1) immunopurified or recombinant human Ago2 cannot be reconstituted with an siRNA duplex to generate a minimal RISC, which exhibits target mRNA cleavage activity (Liu et al., 2004; Rivas et al., 2005); (2) human Ago2 alone cannot stably associate with the siRNA duplex in vitro, as manifested in an electrophoretic mobility-shift assay (Chendrimada et al., 2005); (3) in Drosophila, core components of the RLC are required for loading of the siRNA duplex into Ago2 (Matranga et al., 2005).

Our paper focuses on a complex between Aa-Ago and an externally bound siRNA duplex, thereby addressing issues related to potential protein-RNA recognition events along the RISC-loading pathway. Our structure most likely provides a “snapshot” of the molecular interaction between Ago and the siRNA duplex, which is likely to be transient in the absence of other components of the RLC. This interaction may be too weak for detection by mobility-shift assays (Kd > 10 μM in our filter binding assay), but it appears to be trapped in the process of crystal formation.

There are two copies of Aa-Ago per bound siRNA duplex in the crystallographic asymmetric unit (Figures 1A and 1B). The PAZ domain is packed against the N domain for the cyan-colored Aa-Ago copy containing bound siRNA duplex, where the 2 nt overhang is inserted into the preformed cavity (Figures 2B and 2C). By contrast, the PAZ domain of the magenta-colored Aa-Ago translates away from the N domain (Figure 4A), thereby leaving an empty, preformed cavity within the PAZ-containing module of the magenta-colored Aa-Ago (Figures 4B and 4C). This establishes that the Ago scaffold is locally perturbed upon complex formation with externally bound siRNA duplex, and that changes are restricted to a decreased separation between the PAZ and N domains when the siRNA duplex 2 nt overhang inserts into the preformed cavity.

Role of Tyr119 in siRNA 2 nt 3′-Overhang Recognition

Y119 and R123 are part of helix α3 within linker L1 in the PAZ-containing lobe of Aa-Ago. There is partial conservation of α3 residues among eukaryotic Agos, but there is poor conservation among bacterial Agos (Yuan et al., 2005). Thus, any alignment of α3 residues between bacterial and eukaryotic Agos remains tentative at this time. Tyr119 appears to be critical for molecular recognition, since it stacks over the first overhang base (Figure 2A). Interestingly, there are several candidate aromatic residues around this region in eukaryotic Agos, which suggests that the cavity observed at this region from our bacterial Ago structure may potentially be conserved across the species. It should be noted that previously published data have established formation of a photo-chemical crosslink between the siRNA and Drosophila Ago2 when the siRNA duplex (5-iodoU labeled at the penultimate overhang nucleotide at the 3′ end) was fed into the RLC (Tomari et al., 2004b) under conditions in which Ago2 replaces Dcr-2/R2D2 within the RLC. The increase in crosslink formation correlated with a corresponding decrease in binding of Dcr-2/R2D2.

Importance of the 2 nt 3′ Overhang of the siRNA Duplex

The key structural feature of our complex is the insertion of the 2 nt 3′-end overhang of the siRNA duplex into a preformed cavity located on the outward-facing surface of the PAZ-containing lobe of the bilobal Ago architecture (Figure 2A) that thereby buries 350 Å2 surface area per component upon complex formation. The two overhang bases adopt an extended conformation, with the penultimate overhang base stacked on a conserved tyrosine (Figure 2A) and the terminal overhang base and the intervening sugar-phosphate backbone inserted into the preformed cavity (Figures 2B and 2C).

It has been demonstrated that siRNA duplexes with 2 nt 3′ overhangs are the most efficient in mediating RNA interference (Elbashir et al., 2001), and that the 3′ overhang of the guide strand was specifically anchored into the PAZ domain of Ago (Ma et al., 2004). Recent evidence suggests that the 3′ overhang of siRNA, especially the junction between the single-stranded and the double-stranded region, is also recognized by Dicer (Macrae et al., 2006; Rose et al., 2005; Vermeulen et al., 2005). It is conceivable that, at least in Drosophila, synthesized siRNA re-enters the RNA-interference pathway through interaction with Dicer-containing RLC, leading to the formation of the guide strand-containing RISC. In mammals, Dicer seems to be dispensable for siRNA-induced gene silencing (Kanellopoulou et al., 2005; Murchison et al., 2005). The mechanism for RISC assembly in the absence of Dicer is not clear. Our crystal structure hints that one of the 3′ overhangs, particularly the penultimate overhang nucleotide, is also potentially utilized in the loading of siRNA into Ago proteins, probably to recognize the siRNA.

We cannot discriminate as to whether the strand containing the 3′ overhang is a guide strand or not, since a self-complementary siRNA duplex was used for crystallization of our structure and there is no other RLC component present. However, we are inclined to believe that the 3′ overhang is on the guide strand, given the observation that asymmetric siRNAs with a 3′ overhang only on the guide strand exhibit better cleavage activity than those with a 3′ overhang only on the passenger strand (Vermeulen et al., 2005).

Cavity on the Outward-Facing Surface of the PAZ-Containing Lobe

The previously published structures of Pf-Ago (Song et al., 2004) and Aa-Ago (Yuan et al., 2005) made no mention of a cavity located on the outward-facing surface of the PAZ-containing lobe. We have now identified this preformed Ago surface cavity (Figure 2C), given that it accommodates the 2 nt 3′ overhang of an externally bound siRNA duplex in both 22-mer and 26-mer siRNA complexes. The residues that line the cavity are not conserved among Ago species (partial conservation is observed at Y119), and no specific direct intermolecular contacts are associated with the recognition process. Rather, there appears to be approximate shape complementarity between the extended 2 nt 3′ overhang and the dimensions of the cavity (Figure 2C). The absence of base-specific intermolecular interactions could perhaps be rationalized by the requirement for targeting siRNA duplexes with all combinations of 2 nt overhang elements.

Photochemical Crosslinking Supports the Externally Bound siRNA-Ago Complex Structure

Our photochemical crosslinking data in solution are supportive of the formation of the crystallographically observed externally bound siRNA-Ago complex, given that crosslinking is only observed when the 5-iodoU is positioned at the penultimate overhang nucleotide at the 3′ end of the siRNA duplex (Figure 5D), and the extent of crosslinking is strongly attenuated after mutation of Y119 (Figure 5D and Figure S3). Photochemical crosslink formation requires close proximity between the 5-iodoU and an aromatic amino acid, a requirement consistent with the observed stacking between U21 and Y119 in the crystal structure of the externally bound siRNA-Ago complex (Figure 2A).

We found that 21-mer single-stranded siRNAs crosslinked more efficiently (Figure 5C) than the corresponding siRNA duplexes (Figure 5D), which could reflect the higher binding affinity of Aa-Ago to single-stranded siRNAs than to siRNA duplexes (Yuan et al., 2005). Further, the strongest crosslinking was observed with ss-3, in which the 5-iodoU is positioned at the 5′ end of the radiolabeled strand (Figure 5C). This observation is consistent with the demonstration that the 5′ end of the guide RNA is specifically recognized by Ago proteins (Parker et al., 2005; Ma et al., 2005; Rivas et al., 2005). The observation of two crosslinked bands for ssRNAago complexes (Figure 5C) could reflect stoichiometries for complex formation of one and two ssRNAs bound per Ago within the crosslinked complexes. Alternatively, it could result from the crosslinking of one siRNA to two different positions on the Ago protein.

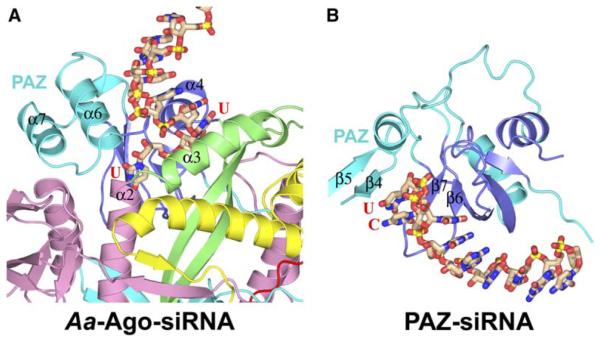

Comparison with the PAZ-siRNA Complex

The crystal structure of the siRNAs bound to the outer surface of the PAZ-containing lobe of Aa-Ago (Figures 3A and 3B) can be compared with the previously reported crystal structure of human PAZ bound to a mini-siRNA duplex (Ma et al., 2004). For simplification, these complexes (Figure 6) are shown with only the 2 nt overhang-containing RNA strand, and they are aligned after the best-possible superposition of the PAZ β barrel core and an α helix (colored blue in Figure 6; remaining PAZ segments are colored cyan). The siRNAago complex is shown in Figure 6A, while the PAZsiRNA complex (Ma et al., 2004) is shown in Figure 6B. This comparison emphasizes that the siRNA 2 nt overhang recognition surface cavity in the Aa-Ago complex and the siRNA 2 nt overhang recognition pocket in the PAZ complex are in close proximity and hence potentially accessible to each other. Nevertheless, the trajectory of the siRNA 2 nt overhang-containing strand is quite distinct in the two complexes, requiring a large change in their mutual alignments during transfer of the siRNA from its externally aligned position in the RISC-loading pathway to its internally aligned position in catalytically competent RISC.

Figure 6. Comparison of Alignments of the Overhang-Anchored Strand in the siRNA-Aa-Ago and PAZ-siRNA-like Complexes.

(A) Alignment of the anchored siRNA strand within the siRNA-Aa-Ago complex. The bases of the UU overhang of the anchored strand are labeled, as are the helices α2 of N domain, α3 of Linker 1, and α6 of the PAZ domain, which participate in formation of the 2 nt overhang recognition cavity.

(B) Alignment of the anchored siRNA strand within the PAZ-siRNA complex (Ma et al., 2004). The bases of the CU overhang of the anchored strand are labeled, as are strands β4, β5, β6, and β7 of the PAZ domain, which are involved in formation of the 2 nt overhang recognition pocket.

The drawings in (A) and (B) were aligned by achieving the best superposition of bluecolored elements (four β strands and one α helix) of the respective PAZ domains (other elements are in cyan). It should be noted that the overhang-containing siRNA strand is positioned differently relative to the PAZ domain in the two complexes.

Future Prospects

One of the key events in the RISC-assembly pathway could involve interactions between siRNA, the Dcr-2/ R2D2 heterodimer associated with the RLC (in Drosophila), and Ago2, the key catalytic component of RISC. Therefore, it is conceivable that the duplex segment and the free 3′-overhang end of siRNA could be targeted by components of the Dcr-2/R2D2 heterodimer, thereby stabilizing the externally bound siRNA-Ago complex (Figure 3). One of the future challenges will be to biochemically characterize for the existence of such potential multimeric alignments during replacement of the Dcr-2/R2D2 heterodimer by Ago2 (Tomari et al., 2004b; Okamura et al., 2004) and follow up with structure determinations in an attempt to elucidate protein-protein and protein-RNA interactions during transfer of siRNA from the RLC to catalytically competent RISC.

Experimental Procedures

Cloning and Protein Expression

The full-length Aa-Ago protein was cloned into the NdeI and BamHI sites of the pET28b vector (Novagen) by PCR amplification from genomic DNA. The protein was expressed in BL21(DE3)/RIL cells cultured in LB medium during an overnight induction period at 20°C with 0.4 mM isopropyl-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at an OD600 of 0.6. Cells were harvested and frozen in liquid nitrogen for storage at −80°C.

The Y119A-containing mutant Aa-Ago gene was made by using the Quickchange kit (Stratagene), and the construct was confirmed by sequencing. The mutant protein was purified as described for the wild-type protein.

Protein Purification

All procedures were performed at 4°C. After thawing, cells were resuspended in 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), complete proteinase inhibitor (Roche), 1.0 M NaCl, 50 mM Tris (pH 7.6) (10 ml/l of culture) and lysed by cell disruptor. After centrifugation (40,000 × g, 1 hr), the supernatant was filtered and loaded onto a Ni2+ affinity column that was equilibrated in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.6) with 1.0 M NaCl. Nonspecific binding proteins were washed out by the same buffer with 25 mM imidazole, prior to elution with 250 mM imidazole in the same buffer. Solid (NH4)2SO4 was added to a final concentration of 1.0 M to the pooled protein from the Ni2+ column, the resulting solution was centrifuged, and the supernatant was loaded onto a fastflow butyl-Sepharose column equilibrated in 1.0 M (NH4)2SO4, 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 50 mM Tris (pH 7.6) prior to elution with a linear gradient to 200 mM (NH4)2SO4 in the same buffer. Pooled fractions from the hydrophobic interaction column were concentrated and then purified on a HiLoad Superdex S-75 26/60 column (Amersham) equilibrated in 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM DTT, and 25 mM Tris (pH 7.6). The purified protein was concentrated to 20 mg/ml in a Centriprep-30 and Centricon-30 (Amicon) and was dialyzed against 250 mM NaCl.

Crystallization and Data Collection

Crystals of native Aa-Ago complexes with 5′-phosphated 22-mer siRNA and 5′-phosphated 26-mer siRNA were grown by hangingdrop vapor diffusion at 20°C. Approximately 15 mg/ml of 1:1 protein-RNA complex in 0.25 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) buffer was mixed with a well solution containing 20% polyethylene glycol 3350, 25 mM NH4F. These crystals grew to a maximum size of 0.15 mm × 0.15 mm × 0.05 mm over the course of 15 days.

For data collection, crystals were flash frozen (100K) in the abovedescribed reservoir solution supplemented with a mixture of cryoprotectants. A total of 360 frames of 1° oscillation were collected for each crystal. The 22-mer siRNA-bound Aa-Ago complex data were collected on beamline X29 at the National Synchrotron Light Source at Brookhaven National Laboratory, whereas the 26-mer siRNA-bound Aa-Ago complex data were collected on our in-house Rigaku diffractometer. The data were processed by HKL2000 (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997). Both crystals belong to space group P21; unit cell parameters are listed in Table 1. There are two protein molecules per RNA duplex in the asymmetric unit, with about 42% solvent content.

Structure Determination

The crystal structures of the siRNA-bound Aa-Ago complexes were solved by using the Aa-Ago structure in free form (PDB ID: 1YVU) as a search model. Molrep (CCP4, 1994) was used to locate two copies of Aa-Ago within one asymmetric unit. The extra density map for duplex siRNA was clear, and the model was traced without ambiguities at an early stage. The model of the siRNA-bound Aa-Ago complex was rebuilt by using the program O (Jones et al., 1991) and was refined by using X-PLOR Version 3.851 (Brunger, 1992) with parameters outlined by Engh and Huber (1991) and REFMAC (CCP4, 1994). The Rfree set contained 5% of the reflections chosen at random. The final model is composed of two copies of Aa-Ago (residues 3–706) and one siRNA duplex.

Photochemical Crosslinking

Reaction mixtures (15 ml) containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 2 pmol Aa-Ago protein, and 0.04 pmol 5′32P-radiolabeled, 5-iodoU-containing single-stranded siRNAs or dsRNA duplexes of equal count per minute were aliquoted into wells of a round-bottom, 96-well plate on ice. The mixtures were irradiated with 312 nm UV light by using a Spectroline Transilluminator inverted directly onto the polystyrene lid of the plate and were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The radioactive crosslinked products were detected and quantified by phosphorimaging.

Cleavage Activity Assay of Aa-Ago

The ssDNA or ssRNA guided cleavage activity assays were performed as described previously (Yuan et al., 2005).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

D.J.P. is supported by funds from the Abby Rockefeller Mauze Trust and the Dewitt Wallace and Maloris Foundations and National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01 AI068776, and T.T. is supported by NIH grant R01 GM068476. Y.P. is supported by the Ruth L. Kirschstein Fellowship from NIH/National Institute of General Medical Sciences. We would like to thank Dr. A. Saxena at X12C and the personnel of beamline X29 at the National Synchrotron Light Source of the Brookhaven National Laboratory for assistance with data collection.

Footnotes

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Data include three figures outlining nonspecific protein-RNA interactions in the complex, that the Aa-Ago Y119A mutant is functionally active, and the time course of the photochemical crosslinking experiments. These figures are available at http://www.structure.org/cgi/content/full/14/10/1557/DC1/.

Accession Numbers

Coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data bank under accession codes 2F8S (22-mer siRNA-bound Aa-Ago) and 2F8T (26-mer siRNA-bound Aa-Ago).

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- Brunger AT. X-PLOR: A System for Crystallography and NMR, Version 3.1. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- CCP4 (Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4) The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1994;50:76–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chendrimada TP, Gregory RI, Kumaraswamy E, Norman J, Cooch N, Nishikura K, Shiekhattar R. TRBP recruits the Dicer complex to Ago2 for microRNA processing and gene silencing. Nature. 2005;436:740–744. doi: 10.1038/nature03868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbashir SM, Martinez J, Patkaniowska A, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Functional anatomy of siRNAs for mediating efficient RNAi in Drosophila melanogaster embryo lysate. EMBO J. 2001;20:6877–6888. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.23.6877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engh RA, Huber R. Accurate bond and angle parameters for X-ray protein structure refinement. Acta Crystallogr. A. 1991;47:381–392. [Google Scholar]

- Filipowicz W. RNAi: the nuts and bolts of the RISC machine. Cell. 2005;122:17–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipowicz W, Jaskiewicz L, Kolb FA, Pillai RS. Posttranscriptional gene silencing by siRNAs and miRNAs. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2005;15:331–341. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, KjeldgAard GJ. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. A. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanellopoulou C, Muljo SA, Kung AL, Ganesan S, Drapkin R, Jenuwein T, Livingston DM, Rajewsky K. Dicer-deficient mouse embryonic stem cells are defective in differentiation and centromeric silencing. Genes Dev. 2005;19:489–501. doi: 10.1101/gad.1248505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim VN. Small RNAs: classification, biogenesis and function. Mol. Cell. 2005;19:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingel A, Sattler M. Novel modes of protein-RNA recognition in the RNAi pathway. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2005;15:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingel A, Simon B, Izaurralde E, Sattler M. Nucleic acid 3′-end recognition by the Argonaute2 PAZ domain. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:576–577. doi: 10.1038/nsmb777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Carmell MA, Rivas FV, Marsden CG, Thomson JM, Song JJ, Hammond SM, Joshua-Tor L, Hannon GJ. Argonaute2 is the catalytic engine of mammalian RNAi. Science. 2004;305:1437–1441. doi: 10.1126/science.1102513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma JB, Ye K, Patel DJ. Structural basis for overhangspecific small interfering RNA recognition by the PAZ domain. Nature. 2004;429:318–322. doi: 10.1038/nature02519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma JB, Yuan YR, Meister G, Pei Y, Tuschl T, Patel DJ. Structural basis for 5′-end-specific recognition of the guide RNA strand by A. fulgidus PIWI protein. Nature. 2005;434:666–670. doi: 10.1038/nature03514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macrae IJ, Zhou K, Li F, Repic A, Brooks AN, Cande WZ, Adams PD, Doudna JA. Structural basis for doublestranded RNA processing by Dicer. Science. 2006;311:195–198. doi: 10.1126/science.1121638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matranga C, Tomari Y, Shin C, Bartel DP, Zamore PD. Passenger-strand cleavage facilitates assembly of siRNA into Ago2-containing RNAi enzyme complexes. Cell. 2005;123:607–620. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murchison EP, Partridge JF, Tam OH, Cheloufi S, Hannon GJ. Characterization of Dicer-deficient murine embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:12135–12140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505479102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura K, Ishizuka A, Siomi H, Siomi MC. Distinct roles for Argonaute proteins in small RNA-directed RNA cleavage pathways. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1655–1666. doi: 10.1101/gad.1210204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of x-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JS, Roe SM, Barford D. Crystal structure of a PIWI protein suggests mechanisms of siRNA recognition and slicer activity. EMBO J. 2004;I23:4727–4737. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JS, Roe SM, Barford D. Structural insights into mRNA recognition from a PIWI-domain-siRNA-guide complex. Nature. 2005;434:663–666. doi: 10.1038/nature03462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham JW, Pellino JL, Lee YS, Carthew RW, Sontheimer EJ. A Dicer-2-dependent 80S complex cleaves targeted mRNAs during RNAi in Drosophila. Cell. 2004;117:83–94. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00258-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas FV, Tolia NH, Song JJ, Aragon JP, Liu J, Hannon GJ, Joshua-Tor L. Purified Argonaute2 and an siRNA form recombinant human RISC. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:340–349. doi: 10.1038/nsmb918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose SD, Kim DH, Amarzguioui M, Heidel JD, Collingwood MA, Davis ME, Rossi JJ, Behlke MA. Functional polarity is introduced by Dicer processing of short substrate RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:4140–4156. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JJ, Smith SK, Hannon GJ, Joshua-Tor L. Crystal structure of Argonaute and its implications for RISC slicer activity. Science. 2004;305:1434–1437. doi: 10.1126/science.1102514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sontheimer EJ. Assembly and function of RNA silencing complexes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:127–138. doi: 10.1038/nrm1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Hall TM. Structure and function of Argonaute proteins. Structure. 2005;13:1403–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomari Y, Zamore PD. Perspective: machines for RNAi. Genes Dev. 2005;19:517–529. doi: 10.1101/gad.1284105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomari Y, Du T, Haley B, Schwarz DS, Bennett R, Cook HA, Koppetsch BS, Theurkauf WE, Zamore PD. RISC assembly defects in the Drosophila RNAi mutant Armitage. Cell. 2004a;116:831–841. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00218-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomari Y, Matranga C, Haley B, Martinez N, Zamore PD. A protein sensor for siRNA asymmetry. Science. 2004b;306:1377–1380. doi: 10.1126/science.1102755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen A, Behlen L, Reynolds A, Wolfson A, Marshall WS, Karpilow J, Khvorova A. The contributions of dsRNA structure to Dicer specificity and efficiency. RNA. 2005;11:674–682. doi: 10.1261/rna.7272305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan YR, Pei Y, Ma JB, Kuryavyi V, Zhadina M, Meister G, Chen HY, Dauter Z, Tuschl T, Patel DJ. Crystal structure of A. aeolicus Argonaute, a site-specific DNA-guided RNA endonuclease, provides insights into RISC-mediated mRNA cleavage. Mol. Cell. 2005;19:405–419. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.