Abstract

The wettability of silicon (Si) is one of the important parameters in the technology of surface functionalization of this material and fabrication of biosensing devices. We report on a protocol of using KrF and ArF lasers irradiating Si (001) samples immersed in a liquid environment with low number of pulses and operating at moderately low pulse fluences to induce Si wettability modification. Wafers immersed for up to 4 hr in a 0.01% H2O2/H2O solution did not show measurable change in their initial contact angle (CA) ~75°. However, the 500-pulse KrF and ArF lasers irradiation of such wafers in a microchamber filled with 0.01% H2O2/H2O solution at 250 and 65 mJ/cm2, respectively, has decreased the CA to near 15°, indicating the formation of a superhydrophilic surface. The formation of OH-terminated Si (001), with no measurable change of the wafer’s surface morphology, has been confirmed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and atomic force microscopy measurements. The selective area irradiated samples were then immersed in a biotin-conjugated fluorescein-stained nanospheres solution for 2 hr, resulting in a successful immobilization of the nanospheres in the non-irradiated area. This illustrates the potential of the method for selective area biofunctionalization and fabrication of advanced Si-based biosensing architectures. We also describe a similar protocol of irradiation of wafers immersed in methanol (CH3OH) using ArF laser operating at pulse fluence of 65 mJ/cm2 and in situ formation of a strongly hydrophobic surface of Si (001) with the CA of 103°. The XPS results indicate ArF laser induced formation of Si–(OCH3)x compounds responsible for the observed hydrophobicity. However, no such compounds were found by XPS on the Si surface irradiated by KrF laser in methanol, demonstrating the inability of the KrF laser to photodissociate methanol and create -OCH3 radicals.

Keywords: Engineering, Issue 105, Silicon, surface wettability, laser-surface interaction, selective area processing, excimer laser, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, contact angle

Introduction

The remarkable electronic and chemical properties as well as its high mechanical strength have made silicon (Si) an ideal choice for microelectronic devices and biomedical chips1. Selective area control of the Si surface has received significant attention for applications involving microfluidic and lab-on-chip devices2,3.This is often obtained either by nano-scale modification of the surface roughness or by chemical treatment of the surface4. The surface roughening or patterning to produce disordered or ordered surface structures on the Si surface include photolithography5, ion beam lithography6 and laser techniques7. Compared with these methods, laser surface texturing process is reported to be less complicated with the potential to produce microstructures with high spatial resolution8. However, as Si has an elevated texturing threshold, requiring irradiation with pulse fluence to induce surface texturing in excess of its ablation threshold (~500 mJ/cm2)9, texturing of Si surface has frequently been assisted by employing reactive gas atmospheres, such as that of a high pressure SF6 environment4,7,8. Consequently, to modify wettability of the Si surface, numerous works have focused on chemical treatment by depositing organic10 and inorganic films2, or using plasma or electron beam surface treatment11,12. It is recognized that hydrophilicity of Si originating from the existence of singular and associated OH groups on its surface could be achieved by boiling it in a H2O2 solution at 100 °C for several minutes13. However, the hydrophobic Si surface states, most of which are due to the presence of Si-H or Si-O-CH3 groups, could be achieved by wet chemical handling involving etching with HF acid solution or coating with photoresist13-15. To achieve selective area control of wettability of Si, complex patterning steps are usually required, including treatment in chemical solutions16. The high chemical reactivity of UV laser radiation has also been used to selective area process organic film coated solid substrates and modify their wettability17. However, a limited amount of data is available on laser-assisted modification of Si wettability by irradiation of samples immersed in different chemical solutions.

In our previous research, UV laser irradiation of III-V semiconductors in air18-20 and NH321 was successfully used to alter the surface chemical composition of GaAs, InGaAs and InP. We established that UV laser irradiation of III-V semiconductors in deionized (DI) water decreases surface oxides and carbides, while the water adsorbed on semiconductor surface increases22. A strongly hydrophobic Si surface (CA~103°) was obtained by ArF laser irradiation of Si samples in methanol in our recent work 23. As indicated by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), this is primarily due to the ability of the ArF laser to photodissociate CH3OH. We have also used KrF and ArF lasers to irradiate Si (001) in a 0.01% of H2O2 in DI water. This allowed us to achieve selective area formation of superhydrophilic surface of Si (001) characterized by the CA of near 15°. The XPS results suggest that this is due to generation of Si-OH bonds on the irradiated surface24.

A detailed description of this new technique using KrF and ArF lasers for selective area in situ modification of the hydrophilic/hydrophobic surface of Si surface in low concentration of H2O2/H2O and methanol solutions is demonstrated in this article. The details provided here should be sufficient to allow similar experiments to be performed by interested researchers.

Protocol

1. Sample Preparation

Use a diamode scribe to cleave an n-type (P-doped) one-side polished Si wafer (resistivity 3.1~4.8 Ω.m) which is 3 inch in diameter, 380 µm thick, into samples of 12 mm x 6 mm; clean the samples in OptiClear, acetone and isopropyl alcohol (5 min for every step).

Etch samples in a ~0.9% HF solution for 1 min to etch away initial oxide; rinse in DI water and dry in high-purity (99.999%) nitrogen (N2).

Store prepared samples in N2 bag to curb their oxidation in air.

2. Irradiate Samples by ArF (λ=193 nm) and KrF (λ=248 nm) Lasers.

Place samples in a 0.74 mm tall chamber and then seal the chamber with a fused silica window that has high transmission in UV (≥90%). Fill the chamber with H2O2/H2O solution in the range of 0.01-0.2 % or with degassed methanol using a microfluidic channel.

Irradiate samples with homogenized ArF or KrF lasers at demagnification of 2.6 and 1.8, respectively. Irradiate only 2 sites on each sample by increasing laser pulses from 100 to 600 in step of 100 pulses through a circular mask (4 mm in diameter). Irradiate the samples in the same way with a “maple leaf” (9 mm x 7.2 mm) mask.

Rinse samples in DI water, dry with N2 flush; place the samples in a sealed container, then quickly fill this container with N2, in order to avoid exposure to air prior to further experiments.

3. Immobilization of Bio-conjugated Nanospheres

Dilute biotin-conjugated and fluorescein stained 40-nm-diameter nanospheres in a pH 7.4 phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 1X) solution to 1012 particles/ml at RT (~25 °C). Immerse ArF or KrF laser irradiated samples for 2 hr in this solution at RT.

Wash samples with PBS to eliminate physically bound fluorescein stained nanospheres on the surface.

4. Surface Characterization

- Contact angle (CA) measurement

- Carry out static CA measurements with a goniometer in an environment of RT and ambient humidity.

- Employ high purity DI water (resistivity 17.95 MΩ·cm) in a micro-syringe; generate similar volume (~5 µl) drops on the sample surface by lowering the micro-syringe to a similar height for every measurement.

- Capture and save the water drops profile images by CCD camera with software. Measure independently 4 different sites with same irradiation conditions.

- Estimate and average the CA values in drop analysis module from ImageJ software; load the image and change it into grayscale; launch the plugin Dropsnake; place roughly a few knots on the drop contour (~10 knots) from left to right to initialize snake; accept the curve connecting these knots and evolve the curve by pressing snake button. Note: contact angles are displayed in the image and the table.

- XPS measurement

- Investigate surface chemical modification with a XPS spectrometer(1x10-9 Torr base pressure) outfitted with an Al Kα source working at 150 W:

- Load the samples into the vacuum chamber.

- Acquire the surface survey data in constant energy modes of 50 eV pass energy from an area of 220 µm x 220 µm.

- Acquire high resolution scans data from the same analyzed area at 20 eV pass energy.

- Process XPS spectra data with XPS spectra quantification software, as referenced25,26.

- Fluorescence microscope imaging

- Excite samples, which were irradiated through “maple leaf” mask and exposed to fluorescein stained nanospheres, using a blue light source (λ=450~490 nm).

- Observe fluorescent images, emitting at 515 nm, with a fluorescence inverted microscope in magnification of 4X.

- Characterize the surface morphology of these samples with AFM, as referenced27.

Representative Results

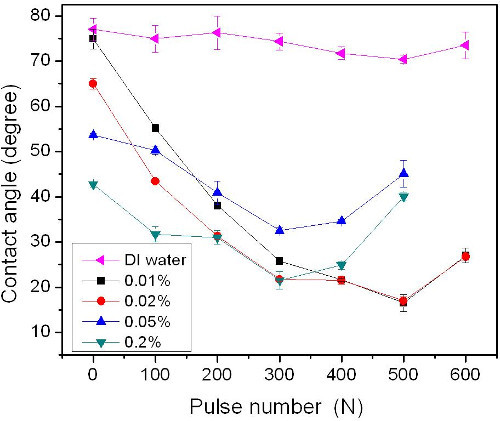

These representative results have been presented in our previous published work23,24. Figure 1 shows the CA vs. N (number of pulses) on sites irradiated by KrF laser at 250 mJ/cm2 in DI H2O for different concentrations of H2O2/H2O solutions (e.g., 0.01, 0.02, 0.05 and 0.2%). The CA decreases with increasing pulse number for all the H2O2 solutions. The minimum CA (~15°) for the 0.02 and 0.01% H2O2 solutions is obtained at 500 pulses. A rather larger CA has been observed for 0.05 and 0.2% H2O2 solutions at larger pulse numbers (N≥500). Concurrently, it is found that the CA of the sample without irradiation (N=0) decreased by 32° from 75° as the H2O2 concentration increased from 0.02 to 0.2%. These results, acquired after an average 10 min exposure to H2O2 solutions, likely represent the CA saturation values obtainable at respective H2O2 concentrations. However, it is important to note that the exposure of samples to 0.01 % H2O2 solution, for up to 4 hr has not resulted in a measurable change of the CA characterizing the initial surface.

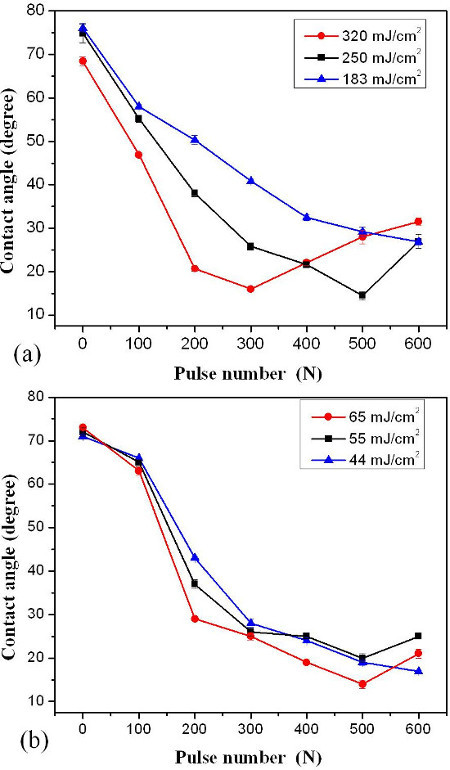

Figure 2 illustrates CA vs. pulse number for the sites after KrF (Figure 2A) and ArF (Figure 2B) laser irradiation in a 0.01% H2O2/H2O solution. Figure 2a demonstrates that the CA decreases continuously with the pulse number up to 600 pulses of the KrF at 183 mJ/cm2. Similar results were found on samples irradiated by ArF laser at 44 mJ/cm2, as shown in Figure 2B. When the sites were irradiated by KrF laser with 300 pulses at 320 mJ/cm2 and 500 pulses at 250 mJ/cm2, a minimum CA value of 15° was obtained. When the sites were irradiated by 500 ArF laser pulses at 65 mJ/cm2, the similar CA~15° was achieved.

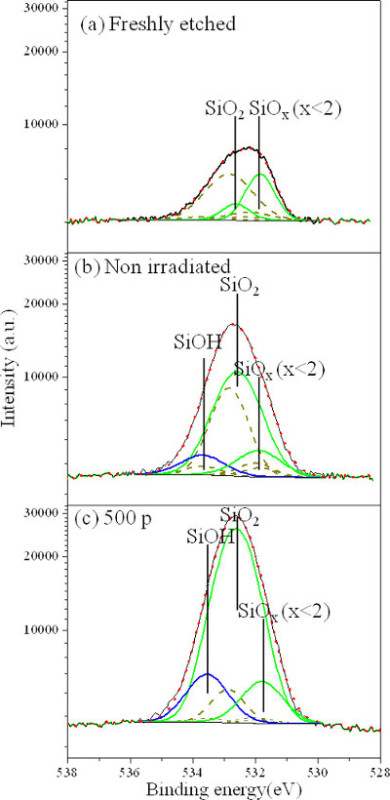

Figure 3 shows O 1s XPS spectra of Si surface freshly etched by HF (Figure 3A), exposed to 0.01% H2O2/H2O solution for approximately 10 min without laser irradiation ((Figure3B), and exposed to 0.01% H2O2/H2O solution and 500-pulse KrF laser irradiation at 250 mJ/cm2 (Figure 3C). The peaks at 531.8±0.1, 532.6±0.1 and 533.7±0.1 eV were assigned to SiOx, SiO2 and SiOH, respectively28,29. Figure 3B shows that the exposure to an HF solution has removed most of SiO2 and SiOx from the surface. The quantities of SiO2 and SiOH on the site irradiated by KrF laser are greater (Figure 3C) than those on the non-irradiated (Figure 3B). The Si surfaces coated with SiO2 were always reported to have minimum CA values of 45°-55°, as referenced11, depending on the O/Si ratio. However, a superhydrophilic SiOH monolayer covered Si surface was reported with a minimum CA of 13°, as referenced30. Thus, the CA=14° obtained with 500 pulses is mainly due to increased surface concentration of SiOH. We also observed that the SiOH/SiO2 ratio increased from 0.10 (100-pulse irradiation, data not shown) to 0.17 for the 500-pulse irradiated site. The dashed lines in the spectra represent the carbon (C) adsorbates on the surface. The quantities of these adsorbates are determined depending on fixed ratios of O/C of C-O, C=O and O-C=O bonds in the C 1s spectra31. We have found that there is more C on the non-irradiated surface exposed to the H2O2/H2O solution, than on the sample freshly etched by HF acid. Figure 3C shows that the quantities of C absorbates decreased with pulse number due to the excimer laser cleaning effect9. Since the C absorbates on the surface were reported to increase hydrophobicity of Si15, the laser induced removal of C adsorbates also improves the hydrophilic nature of the surface.

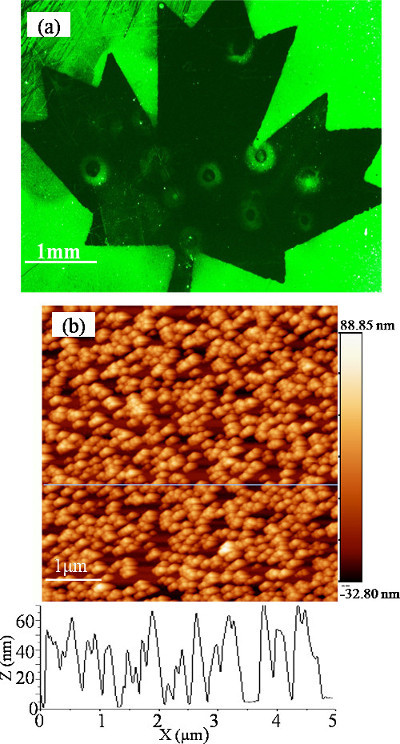

Figure 4A shows a fluorescence microscopic image of the Si surface selectively coated with fluorescein stained nanospheres. The sample was first irradiated in a H2O2/H2O solution (0.01%) by projecting a “maple leaf” mask with the KrF laser delivering 400 pulses at 250 mJ/cm2. High surface concentration of nanospheres is found on the non-irradiated portion of the sample. The result illustrates formation of a laser-induced zone of a strongly hydrophilic material that prevents binding of the nanospheres. The presence of some nanospheres observed in this zone could be related to the surface defect induced oxidation of Si and related reduction in its hydrophilicity. Figure 4B shows an AFM image of a fragment of the non-irradiated surface densely covered with immobilized nanospheres.

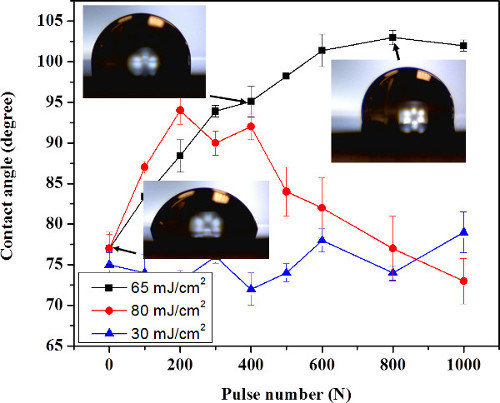

Figure 5 shows the CA values measured for Si samples that were immersed in methanol and irradiated with ArF laser at 30, 65 and 80 mJ/cm2. It can be seen that the CA of the sample irradiated with 800 pulses at 65 mJ/cm2 increased from its initial value of 75° to 103°, and it is comparable to the CA for the 1,000-pulse irradiated sample. This suggests that the laser based chemical alteration of the Si surface saturates at these laser fluences. More intense dynamics of the CA increase has been observed for 80 mJ/cm2 and low number of laser pulses (N < 200), as indicated by the full circle symbols. However, the formation of bubbles on samples irradiated with N>200 pulses, and a related uncontrolled modification of the sample surface morphology prevented us from collecting reliable data under such conditions. Using an approach described elsewhere22,32, we estimated that an ArF laser irradiation at 65 mJ/cm2 induces peak temperature on the surface of Si comparable to the methanol boiling point, i.e., 65 °C, as referenced33. Thus, irradiation with greater laser fluences is expected to induce the formation of bubbles. Consistent with this was our inability to fabricate Si samples of satisfactory characteristics with the laser fluence of 80 mJ/cm2 and N > 200 pulses. In contrast, irradiation at 30 mJ/cm2 showed only a weak increase of the CA to 78° for the 1,000-pulse irradiated samples.

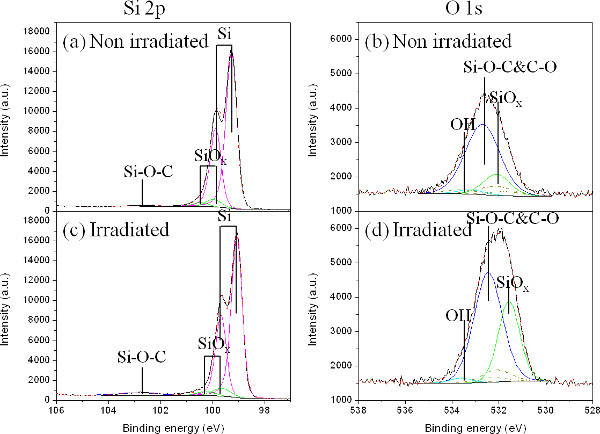

Figure 6 shows XPS spectra of Si 2p and O 1s for sites immersed in methanol that were non-irradiated (Figures 6A and 6B), and irradiated with 500 pulses of the ArF laser at 65 mJ/cm2(Figure 6C and 6D). A weak feature in the Si 2p spectrum of the non-irradiated site (Figure 6A) can be seen around BE=102.7 eV. This feature has been reported to originate from the Si-(OCH3)x bond34. The atomic concentration of this compound has been estimated at 0.7%, which is slightly underestimated due to the relatively small (60°) take-off angle (TOF) applied while collecting XPS data. However, on the irradiated site (Figure 6C), the atomic percentage of Si-(OCH3)x bond increased by 5 times to 3.5% at TOF of 60°. In the O 1s spectra (Figures 6B and 6D), it can be seen that the concentration of the Si-O-CH3 peak (BE=532.6 eV) increased from 1 to 2.5 % for the non-irradiated and irradiated sites, respectively. As Si-(OCH3)x has been reported to be responsible for the formation of a hydrophobic surface of Si, as referenced15,35,36, the increase of surface concentration of Si-(OCH3)x appears to be the main reason for the observed hydrophobic characteristics of the ArF irradiated Si samples. In the O 1s spectra, besides Si-O-C and C-O, there are SiOx and OH peaks. The increase of the SiOx peak at BE=531.5±0.2 eV is possibly caused by the CH3O binding to SiOx sub-oxides (SiOx+1-CH3)34. As the HF treated Si sample didn’t show presence of OH (not shown here), this OH peak is possibly from CH3OH physically absorbed to the Si surface.

Figure 1. Contact angle vs. pulse number on Si (001) surface irradiated by KrF laser at 250 mJ/cm2 in DI H2O and different concentrations H2O2/H2O solutions (e.g., 0.01, 0.02, 0.05 and 0.2%). The contact angle value standard deviation (SD) is 2.5°. The figure has been modified from 24. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 1. Contact angle vs. pulse number on Si (001) surface irradiated by KrF laser at 250 mJ/cm2 in DI H2O and different concentrations H2O2/H2O solutions (e.g., 0.01, 0.02, 0.05 and 0.2%). The contact angle value standard deviation (SD) is 2.5°. The figure has been modified from 24. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2. Contact angle vs. pulse number of samples immersed in 0.01% H2O2/H2O solution and irradiated by KrF (Figure 2A) and ArF (Figure 2B) lasers. The SD of contact angle value was reported to be 2.2°. The figure has been modified from 24. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2. Contact angle vs. pulse number of samples immersed in 0.01% H2O2/H2O solution and irradiated by KrF (Figure 2A) and ArF (Figure 2B) lasers. The SD of contact angle value was reported to be 2.2°. The figure has been modified from 24. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3.O 1s XPS spectra of Si surface freshly etched in HF (A), exposed to 0.01% H2O2/H2O solution for approximately 10 min without laser irradiation (B), and irradiated with 500 pulses of the KrF laser at 250 mJ/cm2 while exposed to 0.01% H2O2/H2O solution (C). The figure has been modified from 24. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3.O 1s XPS spectra of Si surface freshly etched in HF (A), exposed to 0.01% H2O2/H2O solution for approximately 10 min without laser irradiation (B), and irradiated with 500 pulses of the KrF laser at 250 mJ/cm2 while exposed to 0.01% H2O2/H2O solution (C). The figure has been modified from 24. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 4.Fluorescence microscopic picture of a sample that was, first, irradiated with 400 pulses of a KrF laser operating at 250 mJ/cm2 and projecting a “maple leaf” mask on the surface and, second, exposed to a solution of fluorescein stained nanospheres (A). AFM image of a fragment of the non-irradiated part of the sample showing immobilized nanospheres (B). The figure has been modified from 24. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 4.Fluorescence microscopic picture of a sample that was, first, irradiated with 400 pulses of a KrF laser operating at 250 mJ/cm2 and projecting a “maple leaf” mask on the surface and, second, exposed to a solution of fluorescein stained nanospheres (A). AFM image of a fragment of the non-irradiated part of the sample showing immobilized nanospheres (B). The figure has been modified from 24. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 5.Contact angle of Si (001) samples immersed in methanol and irradiated with an ArF laser at 30 mJ/cm2 (▲), 65 mJ/cm2 (■) and 80 mJ/cm2 (●). The error bars are calculated based on the measurements of 3 independent sites. A contact angle value SD of 2.0° was reported. The figure has been modified from 23. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 5.Contact angle of Si (001) samples immersed in methanol and irradiated with an ArF laser at 30 mJ/cm2 (▲), 65 mJ/cm2 (■) and 80 mJ/cm2 (●). The error bars are calculated based on the measurements of 3 independent sites. A contact angle value SD of 2.0° was reported. The figure has been modified from 23. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 6.Si 2p and O 1s XPS spectra of a reference (non-irradiated) sample (A and B), and a sample irradiated by an ArF laser in methanol with 500 pulses of at 65mJ/cm2 (C and D). The figure has been modified from 23. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 6.Si 2p and O 1s XPS spectra of a reference (non-irradiated) sample (A and B), and a sample irradiated by an ArF laser in methanol with 500 pulses of at 65mJ/cm2 (C and D). The figure has been modified from 23. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Discussion

We have proposed a protocol of UV laser irradiation of Si wafer in a microfluidic chamber filled with low concentration of H2O2 solution to induce a superhydrophilic Si surface, which is mainly due to the generation of Si-OH. UV laser photolysis of H2O2 was supposed to form negatively charged OH- radicals. Also, UV laser photoelectric effect leads to the formation of a positively charged surface37. Therefore, the interaction of these negative OH- radicals with a positively charged surface leads to the generation of Si-OH on the surface. So, we can increase hydrophilicity by increasing the laser pulse number and increase the concentration of OH- reacting with Si15. However, the hydrophilicity ceased to increase or even decrease at larger pulse number during the process because H2O2 is thermodynamically unstable, and its decomposition is described by 2H2O2→2H2O+O238, which results in excessively formed O2 in the near surface region of Si. Although this process would potentially lead to the formation of SiO2 to improve the surface hydrophilicity, the generation of O2 molecules could also be the cause of bubbles formation near the irradiated surface. Significantly increased bubble formation by ArF laser at 65 mJ/ cm2 and KrF laser at 320 mJ/cm2, is consistent with the increased possibility of thermally driven decomposition of H2O2. As the minimum CA for SiO2 coated Si is known to be near 45°, the formation SiO2 enriched Si could cause the increase of CA observed for the sites irradiated with a large pulse number.

The calculation of temperature induced by laser irradiation is also a critical aspect, as it is important to the oxidation of Si in the H2O2/H2O solution and the increased wettability. Using COMSOL calculations, the surface peak temperatures were estimated to be 88 and 95 °C when irradiated with KrF laser pulse of 250 and 320 mJ/cm2, respectively. In comparison, the surface peak temperature is estimated to be 40 °C, when it was irradiated by ArF laser pulse of 65 mJ/cm2. These peak temperatures dropped to the original temperature in 10-5 s. There is no heat accumulation between two consecutive pulses when KrF and ArF lasers operate at a repetition rate of 2 Hz (a case investigated in this communication). Based on the temperature calculation results, the laser parameters can be optimized in future experiments.

We also proposed using ArF laser to induce hydrophobic Si surface by irradiating Si sample in methanol solution in a similar microchamber, which is due to laser induced formation of Si-O-CH3 on the irradiated surface, as shown in Figures 5 and 6. It has been reported that UV laser light (105-200 nm) induced dissociation of methanol vapor could be described by the reaction: CH3OH→CH3O+H 39. The higher the temperature, the more CH3O adsorbs on the Si surface40. Thus, by irradiation at lower laser fluence (e.g., 30 mJ/cm2), there is no methanol boiling and no obvious wettability change due to laser induced lower temperature. Also, the KrF laser irradiation of the sample in methanol solution produces no significant CA increment due to its longer wavelength and lower cross section absorption coefficient (<0.1x10-20/cm2) than ArF laser (25 x10-20/cm2)41. The absorption coefficient of KrF laser in methanol is also much lower than those of ArF (61x10-20/cm2) and KrF laser (9x10-20/cm2) in H2O242.The saturation of the CA around 103° is related to the CH3 surface energy, which is dominant for the wettability15. The lower the surface energy, the higher the hydrophobicity. The lowest surface energy (CF3) was reported to have the maximum CA of 120°, while for a CHx bond with higher surface energy, the CA of 110° 43 is always lower.

Therefore, compared with other well-known methods of laser induced modification of Si, such as laser induced surface morphology modification, the process and steps described in this report are simpler, they do not need a high cost and high power laser systems, but are effective in in situ control of Si surface wettability. This technique can be widely used to selective area induce modification of wettability for micro/nano Si based biosensor application in future. However, there are limitations of this technique, especially for UV laser induced hydrophobicity, such as the maximum hydrophobicity (CA) is restricted by the laser photon energy and CHx surface energy. The critical steps during this techniques mainly includes storing the sample in N2 container to avoid oxidation before irradiation and controlling the bubbles generation on Si surface during laser irradiation, e.g., using microfluidic channel.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada (Discovery Grant No. 122795-2010) and the program of the Canada Research Chair in Quantum Semiconductors (JJD). The help provided by Xiaohuan Xuang, Mohamed Walid Hassen and technical assistance of Sonia Blais of the Université de Sherbrooke Centre de caractérisation de matériaux (CCM) in collecting XPS data are greatly appreciated. NL acknowledges the Merit Scholarship Program for Foreign Student, Fonds de recherche du Québec - Nature et technologies, for providing a graduate student scholarship.

References

- Liu X, Fu RKY, Ding C, Chu PK. Hydrogen plasma surface activation of silicon for biomedical applications. Biomol. Eng. 2007;24:113–117. doi: 10.1016/j.bioeng.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayiati P, Tserepi A, Petrou PS, Kakabakos SE, Misiakos K, Gogolides E. Electrowetting on plasma-deposited fluorocarbon hydrophobic films for biofluid transport in microfluidics. J. Appl. Phys. 2007;101:103306–103309. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel S, Chaudhury MK, Chen JC. Fast Drop Movements Resulting from the Phase Change on a Gradient Surface. Science. 2001;291:633–636. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5504.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Zhao XW, Han YH, Gu ZZ. Control of water droplet motion by alteration of roughness gradient on silicon wafer by laser surface treatment. Thin Solid Films. 2008;516:4059–4063. [Google Scholar]

- Krupenkin TN, Taylor JA, Schneider TM, Yang S. From Rolling Ball to Complete Wetting:The Dynamic Tuning of Liquids on Nanostructured Surfaces. Langmuir. 2004;20:3824–3827. doi: 10.1021/la036093q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martines E, Seunarine K, Morgan H, Gadegaard N, Wilkinson CDW, Riehle MO. Superhydrophobicity and Superhydrophilicity of Regular Nanopatterns. Nano Lett. 2005;5:2097–2103. doi: 10.1021/nl051435t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranella A, Barberoglou M, Bakogianni S, Fotakis C, Stratakis E. Tuning cell adhesion by controlling the roughness and wettability of 3D micro/nano silicon structures. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:2711–2720. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorba V, et al. Making silicon hydrophobic: wettability control by two-lengthscale simultaneous patterning with femtosecond laser irradiation. Nanotechnology. 2006;17:3234. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/17/13/026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsu R, Lubben D, Bramblett T, Greene J. Mechanisms of excimer laser cleaning of airexposed Si(100) surfaces studied by Auger electron spectroscopy, electron energyloss spectroscopy, reflection highenergy electron diffraction, and secondaryion mass spectrometry. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A. 1991;9(100):223–227. [Google Scholar]

- Miramond C, Vuillaume D. 1-octadecene monolayers on Si (111) hydrogen-terminated surfaces: Effect of substrate doping. J. Appl. Phys. 2004;96(111):1529–1536. [Google Scholar]

- Chasse M, Ross G. Effect of aging on wettability of silicon surfaces modified by Ar implantation. J. Appl. Phys. 2002;92:5872–5877. [Google Scholar]

- Aronov D, Rosenman G, Barkay Z. Wettability study of modified silicon dioxide surface using environmental scanning electron microscopy. J. Appl. Phys. 2007;101:084901–084905. [Google Scholar]

- Bal JK, Kundu S, Hazra S. Growth and stability of langmuir-blodgett films on OH-, H-, or Br-terminated Si(001) Phys. Rev. B. 2010;81:045404. [Google Scholar]

- Bal J, Kundu S, Hazra S. Hydrophobic to hydrophilic transition of HF-treated Si surface during Langmuir lodgett film deposition. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2010;500:90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Grundner M, Jacob H. Investigations on hydrophilic and hydrophobic silicon (100) wafer surfaces by X-ray photoelectron and high-resolution electron energy loss-spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. A. 1986;39(100):73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, et al. Selective surface modification in silicon microfluidic channels for micromanipulation of biological macromolecules. Biomed. Microdevices. 2001;3:239–244. [Google Scholar]

- Li XM, Reinhoudt D, Crego-Calama M. What do we need for a superhydrophobic surface? A review on the recent progress in the preparation of superhydrophobic surfaces. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:1350–1368. doi: 10.1039/b602486f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubowski J, et al. Enhanced quantum-well photoluminescence in InGaAs/InGaAsP heterostructures following excimer-laser-assisted surface processing. Appl. Phys. A. 1999;69:299–303. [Google Scholar]

- Genest J, Beal R, Aimez V, Dubowski JJ. ArF laser-based quantum well intermixing in InGaAs/InGaAsP heterostructures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008;93:071106. [Google Scholar]

- Genest J, Dubowski J, Aimez V. Suppressed intermixing in InAlGaAs/AlGaAs/GaAs and AlGaAs/GaAs quantum well heterostructures irradiated with a KrF excimer laser. Appl. Phys. A. 2007;89:423–426. [Google Scholar]

- Wrobel JM, Moffitt CE, Wieliczka DM, Dubowski JJ, Fraser JW. XPS study of XeCl excimer-laser-etched InP. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1998;127-129:805–809. [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Dubowski JJ. Chemical evolution of InP/InGaAs/InGaAsP microstructures irradiated in air and deionized water with ArF and KrF lasers. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013;270:16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Hassen WM, Dubowski JJ. Excimer laser-assisted chemical process for formation of hydrophobic surface of Si (001) Appl. Phys. A. 2014. pp. 1–5.

- Liu N, Huang X, Dubowski JJ. Selective area in situ conversion of Si (0 0 1) hydrophobic to hydrophilic surface by excimer laser irradiation in hydrogen peroxide. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2014;47:385106. [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno K, Maeda S, Suzuki K. Photoelectron emission from silicon wafer surface with adsorption of organic molecules. Anal. Sci. 1991;7:345. [Google Scholar]

- Swift JL, Cramb DT. Nanoparticles as Fluorescence Labels: Is Size All that Matters? Biophys. J. 2008;95:865–876. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.127688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Kh Moumanis , Dubowski JJ. Self-organized Nano-cone Arrays in InP/InGaAs/InGaAsP Microstructures by Irradiation with ArF and KrF Excimer Lasers. JLMN. 2012;7:130. [Google Scholar]

- Grunthaner PJ, Hecht MH, Grunthaner FJ, Johnson NM. The localization and crystallographic dependence of Si suboxide species at the SiO2/Si interface. J. Appl. Phys. 1987;61:629–638. [Google Scholar]

- Heo J, Kim HJ. Effects of annealing condition on low-k a-SiOC: H thin films. Electrochem. Solid-st. 2007;10:G11. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Helm C, Israelachvili J. Molecular mechanisms associated with adhesion and contact angle hysteresis of monolayer surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. 1991;95:10736–10747. [Google Scholar]

- Miller D, Biesinger M, McIntyre N. Interactions of CO2 and CO at fractional atmosphere pressures with iron and iron oxide surfaces: one possible mechanism for surface contamination? Surf Interface Anal. 2002;33:299–305. [Google Scholar]

- Stanowski R, Voznyy O, Dubowski JJ. Finite element model calculations of temperature profiles in Nd:YAG laser annealed GaAs/AlGaAs quantum well microstructures. JLMN. 2006;1:17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Westwater JW, Santangelo JG. Photographic Study of Boiling. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1955;47:1605–1610. [Google Scholar]

- Kim JW, Kim HB, Hwang CS. Correlation Study on the Low-Dielectric Characteristics of a SiOC (-H) Thin Film from a BTMSM/O2 Precursor. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 2010;56:89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ishizaki T, Saito N, Inoue Y, Bekke M, Takai O. Fabrication and characterization of ultra-water-repellent alumina-silica composite films. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2006;40:192. [Google Scholar]

- Almásy L, Borbély S, Rosta L. Memory of silica aggregates dispersed in smectic liquid crystals: Effect of the interface properties. EPJ B. 1999;10:509–513. [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Liberman V, O'Neill JA, Wu Z, Osgood RM. Ultraviolet laser-induced ion emission from silicon. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A. 1988;6:1426–1427. [Google Scholar]

- Rice F, Reiff O. The thermal decomposition of hydrogen peroxide. J. Phys. Chem. 1927;31:1352–1356. [Google Scholar]

- Quickenden TI, Irvin JA. The ultraviolet absorption spectrum of liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1980;72:4416–4428. [Google Scholar]

- Andre T. Product pair correlation in CH3OH photodissociation at 157 nm: the OH+ CH3 channel. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011;13:2350–2355. doi: 10.1039/c0cp01794a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng BM, Bahou M, Chen WC, Yui CH, Lee YP, Lee LC. Experimental and theoretical studies on vacuum ultraviolet absorption cross sections and photodissociation of CH3OH, CH3OD, CD3OH, and CD3OD. J. Chem. Phys. 2002;117:1633–1640. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman A, Nelson DD, Jr, Nesbitt DJ. Quantum yields for OH production from 193 and 248 nm photolysis of HNO3 and H2O2. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:6935–6946. [Google Scholar]

- Nishino T, Meguro M, Nakamae K, Matsushita M, Ueda Y. The Lowest Surface Free Energy Based on -CF3 Alignment. Langmuir. 1999;15:4321–4323. [Google Scholar]