Abstract

Phagocytosis is a fundamental process through which innate immune cells engulf bacteria, apoptotic cells or other foreign particles in order to kill or neutralize the ingested material, or to present it as antigens and initiate adaptive immune responses. The pH of phagosomes is a critical parameter regulating fission or fusion with endomembranes and activation of proteolytic enzymes, events that allow the phagocytic vacuole to mature into a degradative organelle. In addition, translocation of H+ is required for the production of high levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are essential for efficient killing and signaling to other host tissues. Many intracellular pathogens subvert phagocytic killing by limiting phagosomal acidification, highlighting the importance of pH in phagosome biology. Here we describe a ratiometric method for measuring phagosomal pH in neutrophils using fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled zymosan as phagocytic targets, and live-cell imaging. The assay is based on the fluorescence properties of FITC, which is quenched by acidic pH when excited at 490 nm but not when excited at 440 nm, allowing quantification of a pH-dependent ratio, rather than absolute fluorescence, of a single dye. A detailed protocol for performing in situ dye calibration and conversion of ratio to real pH values is also provided. Single-dye ratiometric methods are generally considered superior to single wavelength or dual-dye pseudo-ratiometric protocols, as they are less sensitive to perturbations such as bleaching, focus changes, laser variations, and uneven labeling, which distort the measured signal. This method can be easily modified to measure pH in other phagocytic cell types, and zymosan can be replaced by any other amine-containing particle, from inert beads to living microorganisms. Finally, this method can be adapted to make use of other fluorescent probes sensitive to different pH ranges or other phagosomal activities, making it a generalized protocol for the functional imaging of phagosomes.

Keywords: Immunology, Issue 106, Phagocytosis, acidification, acidity, pH, ratiometric imaging, functional imaging, fluorescence microscopy, neutrophil, innate immunity, reactive oxygen species

Introduction

Phagocytosis, the process through which innate immune cells engulf large particles, evolved from the eating mechanism of single-celled organisms, and involves binding to a target, enveloping it with a membrane and pinching the membrane off to form a vacuole within the cytosol called a phagosome. While the phagosomal membrane is derived from the plasma membrane, active protein and lipid sorting, as well as fusion with endomembranes during phagosome formation, transform the phagosome into a distinct organelle within the cell with degradative properties that allow the killing, neutralization and breakdown of the ingested material1-3. This process, called phagosomal maturation, relies on the delivery of a host of proteolytic and microbicidal enzymes, including the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase which transfers electrons into phagosomes producing the strong oxidant O2- and its derivative reactive oxygen species (ROS) 2,4.

The luminal pH of phagosomes has a profound influence on several events required for phagosome function. First, pH influences trafficking of endomembranes in general, as pH-dependent conformational changes of transmembrane trafficking regulators alters the recruitment of trafficking determinants such as Arfs, Rabs and vesicular coat-proteins, which in turn define which vesicles may fuse with phagosomes 5-8. Second, the ionic composition of the phagosomal lumen is also transformed as phagosomes mature, and some ion transporters, such as the Na+/H+ exchanger or ClC family Cl-/H+ antiporters, which promote phagocytic function, rely on H+ translocation 9,10. Similarly, ROS production is intimately linked with phagosomal pH. ROS and its toxic oxidant byproducts have long been recognized as crucial for phagosomal killing in neutrophils 4,11,12, and have been shown to play critical roles in other phagocytes including macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs) and amoeba 13-16. The NADPH oxidase is an electrogenic enzyme that releases H+ in the cytosol as NADPH is consumed, and that requires the simultaneous transfer of H+ through companion HVCN1 channels alongside the transported electrons into the phagosomal lumen, in order to alleviate the massive depolarization that would otherwise lead to self-inhibition of the enzyme 17-21. Finally, several proteolytic enzymes have optimal activity at different pH, so time-dependent phagosomal pH changes can influence which enzymes are active and when. The importance of phagosomal pH is highlighted by organisms such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Franciscella tularensis and Salmonella typherium that subvert phagocytic killing at least in part by altering phagosomal pH 22-24.

In mammals the main phagocytes are neutrophils, macrophages and dendritic cells, and depending on cell type, time-dependent phagosomal pH changes can vary widely, and appear to play different roles. In macrophages a strong and rapid acidification mediated by the ATP-dependent proton pump vacuolar ATPase (V-ATPase) is one of the key factors mediating killing 25-27, resembling the mechanisms present in amoeba that use phagocytosis as an eating mechanism 28. In these cells activation of acidic proteases is thought to play a key role. In contrast, neutrophil killing relies more on ROS as well as HOCl produced by myeloperoxidase (MPO)11, and the pH remains neutral or alkaline during the first 30 min acidifying only later 29,30. Neutral pH has been suggested to favor the activity of oxidative proteases such as certain cathepsins. In DCs phagosomal pH is controversial, with some reporting acidification and others neutral or alkaline pH 31,32, but ROS and pH may profoundly influence the ability of these cells to present antigens to T cells, one of their main functions 33.

Importantly, hormones, chemokines and cytokines may produce signaling events that induce maturation and changes in phagocyte behavior, and in turn influence phagosomal pH 34,35. Similarly, drugs, for example the antimalarial chloroquine, which is also considered for anti-cancer therapies 36, may affect phagosomal pH and therefore immune outcomes. Thus, a variety of cell biologists, immunologists, microbiologists and drug developers may be interested in measuring phagosomal pH when seeking to understand the mechanisms underlying the effects of a particular genetic disruption, bioactive compound or microorganism on innate and adaptive immune responses.

Here we describe a method for measuring phagosomal pH in neutrophils that allowed us to show the importance of the HVCN1 channel in regulating neutrophil phagosomal pH 19. The method is based on the ratiometric property of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) whose fluorescence emission at 535 nm is pH sensitive when excited at 490 nm but not 440 nm 37. When this dye is chemically coupled to a target, in this case zymosan, it can be followed using wide-field fluorescence microscopy, where cells are imaged as they phagocytose, and phagosomal pH changes are measured in real time as the phagosome matures. The actual pH is then gleaned by performing a calibration experiment where cells that have phagocytosed are exposed to solutions of different pH that contain the ionophores nigericin and monensin, that allow the rapid equilibration of the pH within phagosomes with the external solution. Ratio values are then compared to the known pH of solutions, a calibration curve is constructed by nonlinear regression and the resulting equation used to calculate pH from the ratio value.

Protocol

Ethics Statement: All animal manipulations were performed in strict accordance with the guidelines of the Animal Research Committee of the University of Geneva.

1. Preparation of Phagocytic Targets

Add 20 mg of dried zymosan to 10 ml sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Vortex and heat in a boiling water bath for 10 min. Cool and centrifuge at 2,000 x g for 5 min.

Remove the supernatant, resuspend in 1 ml PBS and sonicate for 10 min in a water bath sonicator. Transfer 500 µl to two 1.5 ml tubes. Centrifuge at 11,000 x g for 5 min.

Repeat the wash with 500 µl PBS. The boiled zymosan may be aliquoted, frozen and stored at -20 °C.

Wash zymosan twice in 500 µl freshly prepared 0.1 M Na2CO3, pH 9.3 as above (step 1.2).

Resuspend in 490 µl after the final wash. Add 10 µl of 10 mg/ml FITC dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), vortex, cover with foil, and incubate with agitation for 4 hr at RT.

To remove unbound dye, wash as above (step 1.2), first with 0.5 ml DMSO + 150 µl PBS, then 0.5 ml DMSO + 300 µl PBS, then 0.5 ml DMSO + 450 µl PBS, then PBS alone.

Count zymosan using a haemocytometer. Add 1 µl of zymosan to 500 µl PBS, vortex, then add 10 µl to the edge of the haemocytometer chamber, where it meets the coverslip placed over the central grid. Mount the haemocytometer on a bright-field microscope equipped with a 20X objective.

Focus on the upper left-hand corner containing 16 squares and count all zymosan particles in this area using a hand tally counter. Repeat with the lower right-hand corner. Calculate the zymosan concentration using the following equation: Zymosan concentration = Count/2 x 500 x 104 zymosan/ml. Labeled zymosan may be aliquoted, frozen and stored at -20 °C.

Opsonize the labeled zymosan with a rabbit anti-zymosan antibody at 1:100 dilution. Vortex and incubate for 1 hr in a 37 °C water bath. Wash with 500 µl PBS as above (step 1.2). Note: Sonication is highly recommended, particularly after opsonization, as zymosan tends to form clumps that can make analysis more difficult later on. Opsonization with 65% v/v rat or human serum may be used as an alternative.

Count zymosan using a haemocytometer as described in steps 1.7-1.8, and dilute to 100 x 106 particles/ml. Opsonization with other phagocytic stimulators, such as complement or no opsonization, may be alternatively performed.

2. Live Video Microscopy

- Isolate primary mouse neutrophils as described in detail elsewhere38.

- Alternatively, use any phagocytic cell type. Keep neutrophils on ice in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum (v/v), 200 U penicillin/streptomycin, at a concentration of 10 x 106 cells/ml until ready for use. Other cell types may be seeded 1-4 days before.

Add 2 x 105 (20 µl) of neutrophils to the center of a 35 mm glass-bottom dish, spread the drop by adding 50 µl of medium and incubate at 37 °C for 5 min to allow cells to adhere.

Add 1 ml of Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) warmed to 37 °C containing the specific MPO inhibitor 4-aminobenzoic hydrazide (4-ABH, 10 µM). Non-specific MPO inhibitors, such as sodium azide (5 mM), may also be used but have been recently suggested to exert additional non-specific effects on pH 39.

Mount the dish on a widefield fluorescence microscope equipped with a 37 °C heating system and a 40X oil objective. Incubate cells without imaging for 10 min to allow cells and equipment to equilibrate.

Adjust the microscope settings to acquire a bright-field transmission image [phase or differential interference contrast (DIC) if available] with 440 nm or 490 nm excitation and 535 nm emission every 30 sec.

Adjust exposure time and acquisition frequency according to the microscope system to avoid too much photobleaching and phototoxicity and depending on the experimental questions being asked. Begin image acquisition.

After 2 min, add 10 x 106 (50 µl) opsonized FITC-zymosan to the center of the dish. Adjust target:cell ratios depending on the type of phagocyte and target used.

Continue imaging for 30 min. After 30 min stop the time-lapse acquisition and start a timer. Move the stage and capture 10 or more snapshots in different fields of view to image other phagosomes, all within 5 min.

3. Calibration and Control Experiments

Prepare the pH calibration solutions (recipes are described in Table 1) prior to the day of experiment and freeze in 10 ml aliquots. Thaw the calibration solutions and warm to 37 °C in a water bath. Check the pH with a pH meter and record the actual pH of solutions.

Mount a peristaltic pump on the glass bottom dish prior to image acquisition and perform live video microscopy as described above (section 2).

At the end of the 30 min acquisition period turn the pump on to remove the solution within the dish, add 1 ml of the first calibration solution and stop the pump.

- Wait until the signal stabilizes, usually 5 min. Repeat with each calibration solution.

- Perform at least one calibration per experimental day, and calibrate starting with the highest pH and working sequentially to the lowest, as well as starting from the lowest pH and working sequentially towards the highest.

As a control, add 100 µl of 100 µM NADPH oxidase inhibitor diphenyl propionium iodide (DPI) diluted in HBSS to cells in 900 µl HBSS in the glass bottom dish, and incubate for 10 min.

Start acquisition and add zymosan as above (step 2.7). After 15 min of phagocytosis, add 10 µl of 10 µM V-ATPase inhibitor concanamycin A (ConcA) diluted in HBSS and continue imaging for an additional 15 min.

4. Analysis

- Analysis of time-lapse movies and phagosome snapshots. Note: The following instructions are specific for ImageJ. Step-by-step instructions may vary widely depending of the software used, but the functions described in this section are available in most professional image analysis software.

- Open the images with professional image analysis software. Subtract the background in the 490 channel by drawing a small square ROI with the square polygon selection tool in an area where there are no cells, and clicking Plugins> BG Subtraction from ROI. Then upload the same ROI on the 440 channel by clicking Edit> Selection> Restore Selection and repeat.

- Make a 32-bit ratio image of the 490 channel divided by the 440 channel by clicking Process>Image Calculator… , selecting the appropriate images in the Image1 and Image2 drop-down menus, then selecting ‘Divide’ in the Operation drop-down menu, and checking the 32-bit (float) result check-box.

- Change the color-coding look-up table to a ratio-compatible color-coding by clicking Image> Lookup Tables> Rainbow RGB. Threshold the ratio image to eliminate 0 and infinity pixels by clicking Image> Adjust> Threshold…. Adjust the scroll bars so that zymosan appears in red and click Apply, making sure the Set background pixels to NaN check box is selected.

- Combine this ratio stack with the bright-field channel into a multi-channel composite by clicking Image> Color> Merge Channels, and selecting the bright-field image in the gray channel dropdown menu and the ratio image in the green channel dropdown menu, and selecting the Keep source images check-box. Scan the time-lapse movies or snapshots to determine which phagosomes are to be analyzed. The bright-field channel is useful for this.

- Draw regions of interest (ROI) using the oval polygon selection tool around phagosomes, and add them to the ROI manager by clicking Analyze> Tools > ROI Manager> Add. Measure their zymosan intensity ratio by clicking More> Multi-Measure and de-selecting the One row per slice check-box.

- For time-lapse movies, track phagosomes one at a time by drawing an ROI, typing Ctrl+M to measure each time point, and moving the ROI when necessary to track intensity values over time. Copy the measurements from the Results window into a spreadsheet software. Note: Analysis of 15 (5 time courses per experiment x 3) independent experiments is ideal, but more or less may be required depending on the variability observed. Saving the ROIs is always recommended. Some software packages allow image registration and dynamic update of ROIs, facilitating this part of the analysis.

- Conversion from fluorescence to pH values

- Measure the 490/440 ratio for phagosomes in the calibration time-lapse movies as described in section 4.1.

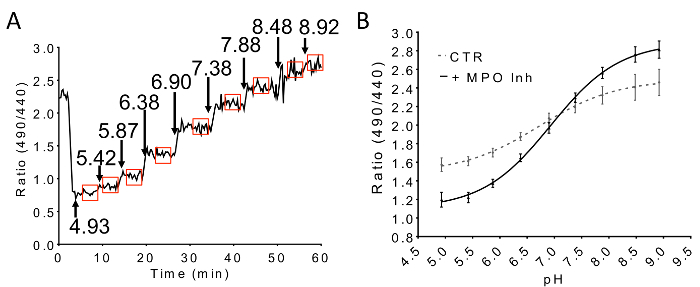

- In a spreadsheet, plot the ratio values over time, and calculate the average ratio values from all phagosomes within the field of view (usually, between 5-20) from 5 time-points within the middle of the time period corresponding to each pH calibration solution. (See also the red boxes in Figure 5A.)

- Plot these average 490/440 ratio values against the actual measured pH. Combine at least 3 independent calibrations into a single graph. Use a statistical or numerical software package to perform a nonlinear regression (best fit curve), usually to a sigmoidal equation. Note: For example, in Figure 5B the equation used was a Boltzmann sigmoidal [Y = Bottom + ((Top-Bottom)/(1+EXP((V50-X)/Slope))], where Y values are the 490/440 ratios, X are the pH values and the Top, Bottom, V50 and slope parameters are calculated by the software.

- Use the obtained equation to transform ratio values to pH. Note: For example, in Figure 5B the equation obtained for the calibration curve in the presence of sodium azide is 490/440 Ratio = 1.103 + [(2.89-1.103)/(1+EXP((6.993-pH)/0.9291)]. Solving for pH gives the following equation: pH = 6.993 - 0.9291*[LN((1.178/(Ratio-1.103))-1))].

Representative Results

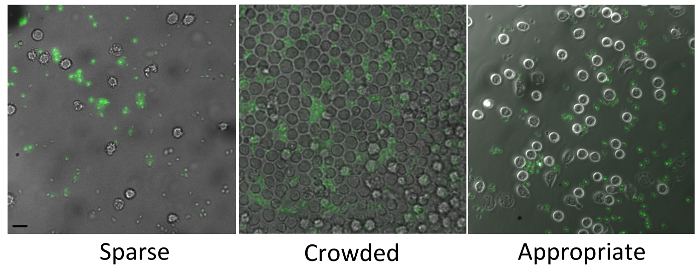

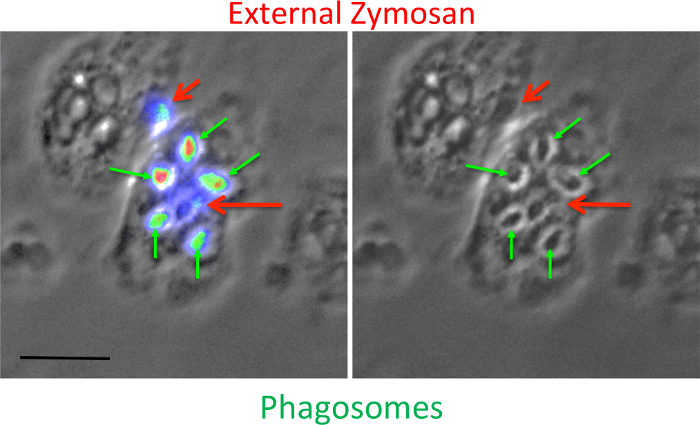

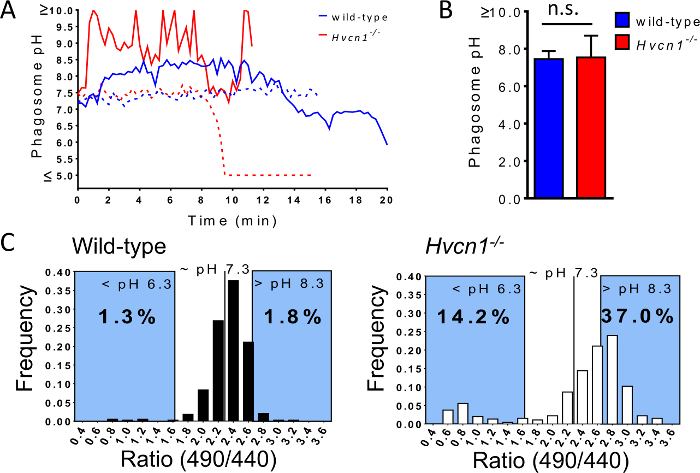

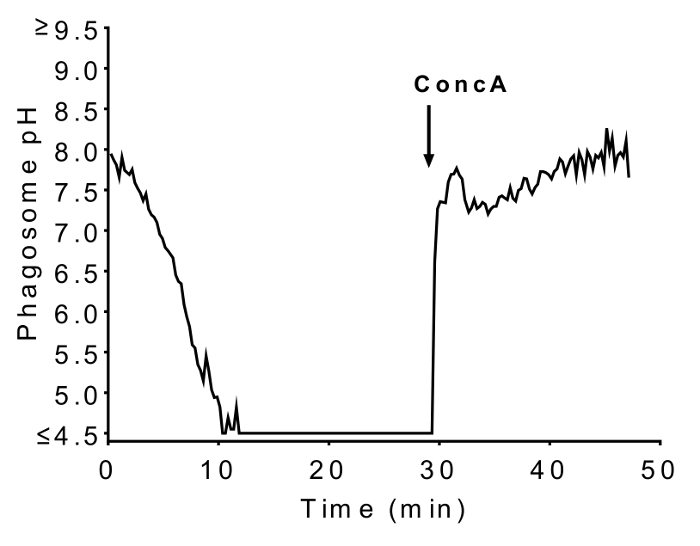

The following are representative results for an experiment where the phagosomal pH of primary mouse neutrophils isolated from the bone-marrow of wild-type or Hvcn1-/-mice were compared. For a successful experiment, it is important to obtain enough phagosomes within the field of view during the whole duration of the time-lapse movie, while avoiding too many phagosomes, which will later be more difficult to segment during the image analysis. Figure 1 shows examples of good and bad confluencies. For time-dependent and snapshot analyses, external zymosan particles must be distinguished from phagosomes and excluded from the analysis. Figure 2 illustrates how the bright-field image can be useful to help distinguish external zymosan particles from phagosomes. Figure 3 shows examples of typical phagosome pH time-courses in wild-type as compared to Hvcn1-/- neutrophils, average pH values, and histograms of phagosomal pH populations. These results highlight a situation where average population pH is unchanged while the distribution of pH strongly differs. Good controls are always important. Figure 4 illustrates the effect of adding the NADPH oxidase inhibitor DPI, which results in a rapid acidification, followed by addition of the V-ATPase inhibitor ConcA, which reverses the acidification. Such experiments can be critical to prove that the pH-sensitive probes are working within phagosomes as they should. A typical calibration time-course is represented in Figure 5, with rectangles indicating the range of ratio values used to construct the calibration curve. Figure 5 additionally shows how dye chlorination through MPO activity can influence the intraphagosomal pH-response of FITC, highlighting the fact that probes may respond differently than expected within the phagosomal environment and the importance of in situ calibration.

Figure 1. Appropriate confluency and target:cell ratio. The left panel shows an example where cell confluency is too sparse and the target:cell ratio is too low, diminishing the probability that a phagocytic event will occur in the field of view. The middle panel shows an example where cell confluency is too high and cells are crowded. Under these conditions, cells may not have enough room to move and find their targets, or may crawl over each other making analysis more difficult later on. The right panel shows an ideal cell confluency and initial target:cell ratio, where many cells and targets can been seen and yet still be clearly distinguished from each another. FITC-zymosan is shown in green and the scale bar represents 10 µm. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 1. Appropriate confluency and target:cell ratio. The left panel shows an example where cell confluency is too sparse and the target:cell ratio is too low, diminishing the probability that a phagocytic event will occur in the field of view. The middle panel shows an example where cell confluency is too high and cells are crowded. Under these conditions, cells may not have enough room to move and find their targets, or may crawl over each other making analysis more difficult later on. The right panel shows an ideal cell confluency and initial target:cell ratio, where many cells and targets can been seen and yet still be clearly distinguished from each another. FITC-zymosan is shown in green and the scale bar represents 10 µm. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2. Distinguishing phagosomes and uningested zymosan. The left panel shows a merged bright-field image and a 490/440 FITC-zymosan ratio, whereas the right panel shows the bright-field image alone. Phagosomes (small green arrows) can be distinguished from external particles, that either do not co-localize with cells (short red arrow) or whose fluorescence does not match up with a dark center (long red arrow) surrounded by a brighter ring, characteristic of phagosomes in the bright-field image (green arrows). The scale bars represents 10 µm. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2. Distinguishing phagosomes and uningested zymosan. The left panel shows a merged bright-field image and a 490/440 FITC-zymosan ratio, whereas the right panel shows the bright-field image alone. Phagosomes (small green arrows) can be distinguished from external particles, that either do not co-localize with cells (short red arrow) or whose fluorescence does not match up with a dark center (long red arrow) surrounded by a brighter ring, characteristic of phagosomes in the bright-field image (green arrows). The scale bars represents 10 µm. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3. Time courses, average pH and ratio histograms of wild-type and Hvcn1-/- neutrophil phagosomes. (A) Typical time courses of phagosomal pH shows that whereas in wild-type neutrophils (blue) the pH is neutral (dotted line) or slightly alkaline (solid line) during early time-points following ingestion, the phagosomes of Hvcn1-/- neutrophils (red) can either alkalinize (solid line) or acidify (dotted line). (B) Compiling snapshots taken 30-35 min after addition of targets allows the average population phagosomal pH to be calculated from a large number of phagosomes (wild-type: n=5/1898/383 and Hvcn1-/-: n=6/1433/451 experiments/phagosomes/cells, bars are means ± SEM, n.s. not significant). (C) Histograms of FITC-zymosan ratios reveal differences in phagosomal pH between wild-type and Hvcn1-/- neutrophils. (This figure has been modified from [19], with permission.) Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3. Time courses, average pH and ratio histograms of wild-type and Hvcn1-/- neutrophil phagosomes. (A) Typical time courses of phagosomal pH shows that whereas in wild-type neutrophils (blue) the pH is neutral (dotted line) or slightly alkaline (solid line) during early time-points following ingestion, the phagosomes of Hvcn1-/- neutrophils (red) can either alkalinize (solid line) or acidify (dotted line). (B) Compiling snapshots taken 30-35 min after addition of targets allows the average population phagosomal pH to be calculated from a large number of phagosomes (wild-type: n=5/1898/383 and Hvcn1-/-: n=6/1433/451 experiments/phagosomes/cells, bars are means ± SEM, n.s. not significant). (C) Histograms of FITC-zymosan ratios reveal differences in phagosomal pH between wild-type and Hvcn1-/- neutrophils. (This figure has been modified from [19], with permission.) Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 4. Effects of NADPH oxidase inhibitor DPI and V-ATPase inhibitor ConcA on phagosomal pH. Pre-incubation in 10 µM DPI resulted in a rapid acidification of phagosomes shortly after ingestion, which was reversed by addition of 100 nM ConcA (arrow). (This figure has been modified from [19], with permission.) Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 4. Effects of NADPH oxidase inhibitor DPI and V-ATPase inhibitor ConcA on phagosomal pH. Pre-incubation in 10 µM DPI resulted in a rapid acidification of phagosomes shortly after ingestion, which was reversed by addition of 100 nM ConcA (arrow). (This figure has been modified from [19], with permission.) Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 5. pH calibration time-course and effects of MPO inhibition on the calibration of FITC-zymosan. (A) A typical pH calibration curve of intraphagosomal FITC-zymosan. Red boxes indicate the range of ratio values used to construct the calibration curve. The actual pH values of the solutions used and the times at which the solutions are changed are indicated by arrows. The curve represents the mean of 10 phagosomes within a single field of view. (B) Inhibition of MPO with the non-specific inhibitor sodium azide (5 mM, MPO Inh) increases the dynamic range of intraphagosomal FITC-zymosan pH-dependent responses. Points are means ± SEM (This figure has been modified from [19], with permission.) Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 5. pH calibration time-course and effects of MPO inhibition on the calibration of FITC-zymosan. (A) A typical pH calibration curve of intraphagosomal FITC-zymosan. Red boxes indicate the range of ratio values used to construct the calibration curve. The actual pH values of the solutions used and the times at which the solutions are changed are indicated by arrows. The curve represents the mean of 10 phagosomes within a single field of view. (B) Inhibition of MPO with the non-specific inhibitor sodium azide (5 mM, MPO Inh) increases the dynamic range of intraphagosomal FITC-zymosan pH-dependent responses. Points are means ± SEM (This figure has been modified from [19], with permission.) Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

| 1.1 | (2x) Base | |||||

| Buffers | Stock | Final (1x) | For 500 ml (2x) | |||

| KCl | 1 M | 140 mM | 140 ml | |||

| MgCl2 | 1 M | 1 mM | 1 ml | |||

| EGTA | 1 M | 0.2 mM | 0.2 ml | |||

| NaCl | 1 M | 20 mM | 20 ml | |||

| 1.2 | Buffers | Stock | Final (1x) | Purpose | ||

| MES | 1 M | 20 mM | for pH 5.5-6.5 | |||

| HEPES | 1 M | 20 mM | for pH 7.0-7.5 | |||

| Tris | 1 M | 20 mM | for pH 5.5-6.7 | |||

| NMDG | 1 M | 20 mM | for pH 5.5-6.8 | |||

| 1.3 | Ionophores | Stock (100% EtOH) | Final (1x) | |||

| Nigericin | 5 mg/ml | 5 µg/ml | ||||

| Monensin | 50 mM | 5 µM | ||||

| 1.4 | For 50 ml | |||||

| pH | 2x Base | Buffer Type | Buffer Vol. | Nigericin | Monensin | |

| 5.0 | 25 ml | MES | 1 ml | 50 µl | 5 µl | |

| 5.5 | 25 ml | MES | 1 ml | 50 µl | 5 µl | |

| 6.0 | 25 ml | MES | 1 ml | 50 µl | 5 µl | |

| 6.5 | 25 ml | MES | 1 ml | 50 µl | 5 µl | |

| 7.0 | 25 ml | HEPES | 1 ml | 50 µl | 5 µl | |

| 7.5 | 25 ml | HEPES | 1 ml | 50 µl | 5 µl | |

| 8.0 | 25 ml | Tris | 1 ml | 50 µl | 5 µl | |

| 8.5 | 25 ml | Tris | 1 ml | 50 µl | 5 µl | |

| 9.0 | 25 ml | Tris | 1 ml | 50 µl | 5 µl | |

| 9.5 | 25 ml | NMDG | 1 ml | 50 µl | 5 µl | |

| Adjust pH with KOH or HCl |

Table 1. Recipe for preparing calibration solutions. 1.1) Recipe for preparing 500 ml of a 2x base solution. 1.2) Recipe for preparing the different buffers used according to the pH of the calibration solution. 1.3) Recipe for preparing the ionophores used in the calibration solutions. 1.4) Recipe for preparing 50 ml of each calibration solution using the base, buffers and ionophores described in 1.1-1.3.

Discussion

Although more time consuming than alternative methods, such as spectroscopy and FACS, which employ a similar strategy of using a pH sensitive dye coupled to targets but measure the average pH of a population of phagosomes, microscopy offers several advantages. First is that internal and external bound, but not internalized, particles can easily be distinguished without having to add other chemicals, such as trypan blue or antibodies, to quench or label external particles, respectively. Second is that following the cells in real time allows researchers to observe multiple aspects of the phagocytic process simultaneous and so effects on migration, sensing and binding particles might be easily discerned here, whereas it might be overlooked with population based methods. Additionally, synchronization of the initiation of phagocytosis, often performed by placing cells at 4 °C, which might perturb other trafficking events due to cold shock 40,41, is not necessary as time zero can be discerned directly. Indeed, when performing live microscopy, this 4 °C synchronization technique is not recommended if capturing periods of time close to the initiation of phagocytosis as the condensation that forms on the bottom of the dish during the temperature shift can mix with the objective immersion oil and temperature differences between the warming dish and microscope components can cause focus shifts. A third advantage stems from the fact that phagosomes are intrinsically heterogeneous on several parameters including, but not limited to, pH 42, and certain effects on phagosome pH might be more subtle, changing the distribution of the phagosomal pH rather than the average population, as was shown in Figure 3. Such observations may give deeper mechanistic insights into the regulation of phagosomal pH.

In the present study, FITC was chosen as the pH sensitive dye of choice because it is inexpensive, widely available, and importantly has a pKa of 6.5 with a dynamic range encompassing pH 3 to 9 in its free form37, which matched the originally anticipated pH range of neutral to slightly alkaline, according to previous studies 29,30. More recently a study employing a different pH probe called SNARF, which has a more basic pKa of 7.5, unexpectedly estimated pH values ranging 1-2 pH units more alkaline for both wild-type and Hvcn1-/- neutrophil phagosomes 39. Thus, the choice of the pH sensor is an important parameter to consider depending on the application. In principle, the method presented here can be easily adapted to employ other pH-sensitive dyes, such as SNARF and 2',7'-bis-(2-carboxyethyl)-5-(and-6)-carboxyfluorescein (BCECF), whose succinimidyl-ester derivatives are easily coupled to amine-containing particles, such as zymosan. Indeed, sensors need not be limited to fluorescent dyes, as ratiometric pH sensitive proteins, such a SypHer 43, could be transduced and expressed by microorganisms. Several non-ratiometric alternatives also exist, notably the red version of the dye pHrodo, which may be used in conjunction with green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged proteins or the pH-sensitive protein pHluorin. However, because of the potentially large effects that the harsh intraphagosomal milieu can have on dyes and proteins targeted therein, these probes should be at minimum combined with pH insensitive probes to be employed in deriving a pseudo-ratio. As exemplified in Figure 5, calibrations experiments can expose the effects of dye damage as a reduced or distorted dynamic range. On a practical note, calibration experiments are not always perfect and may be unfeasible to perform after every experiment. Consequently, ratio values may occasionally fall out of the range of the calibration and yield impossible values upon conversion to pH. It may be appropriate to either express these off-scale values as “greater/less-than or equal to” maximum and minimum calibration pH values, or to express all values as ratios and estimate pH ranges that average ratios represent.

As highlighted by DPI and ConcA controls, ROS production and V-ATPase activity are major factors that determine phagosomal pH. Indeed, in many situations, changes in levels of ROS production may underlie differences in phagosomal pH, particularly in neutrophils, and measurement of phagosomal ROS production and pH often go hand in hand. One word of caution is that both drugs lend insight into the activity of the enzymes they inhibit but not to their location within the cell. Both enzymes are multi-subunit complexes whose individual components must traffic to phagosomes 4, and their lack of activity on phagosomes may result from trafficking or assembly defects rather than direct effects.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors are financially supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation through an operating grant N° 31003A-149566 (to N.D.), and The Sir Jules Thorn Charitable Overseas Trust through a Young Investigator Subsidy (to P.N.).

References

- Yeung T, Grinstein S. Lipid signaling and the modulation of surface charge during phagocytosis. Immunol Rev. 2007;219:17–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannagan RS, Jaumouille V, Grinstein S. The cell biology of phagocytosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2012;7:61–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011811-132445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairn GD, Grinstein S. How nascent phagosomes mature to become phagolysosomes. Trends Immunol. 2012;33(8):397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes P, Demaurex N, Dinauer MC. Regulation of the NADPH oxidase and associated ion fluxes during phagocytosis. Traffic. 2013;14(11):1118–1131. doi: 10.1111/tra.12115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder B, Holzhutter HG. A hypothetical model of cargo-selective rab recruitment during organelle maturation. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2012;63(1):59–71. doi: 10.1007/s12013-012-9341-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado-Lorenzo A, et al. V-ATPase interacts with ARNO and Arf6 in early endosomes and regulates the protein degradative pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8(2):124–136. doi: 10.1038/ncb1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz OA. Acidification and protein traffic. Int Rev Cytol. 2003;226:259–319. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(03)01005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh KK, Grinstein S. Regulation of vacuolar pH and its modulation by some microbial species. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2007;71(3):452–462. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00003-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vito P. The sodium/hydrogen exchanger: a possible mediator of immunity. Cell Immunol. 2006;240(2):69–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreland JG, Davis AP, Bailey G, Nauseef WM, Lamb FS. Anion channels, including ClC-3, are required for normal neutrophil oxidative function, phagocytosis, and transendothelial migration. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(18):12277–12288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winterbourn CC, Kettle AJ. Redox reactions and microbial killing in the neutrophil phagosome. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18(6):642–660. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seredenina T, Demaurex N, Krause KH. Voltage-Gated Proton Channels as Novel Drug Targets: From NADPH Oxidase Regulation to Sperm Biology. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kotsias F, Hoffmann E, Amigorena S, Savina A. Reactive oxygen species production in the phagosome: impact on antigen presentation in dendritic cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18(6):714–729. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm MJ, et al. Monocyte- and macrophage-targeted NADPH oxidase mediates antifungal host defense and regulation of acute inflammation in mice. J Immunol. 2013;190(8):4175–4184. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West AP, et al. TLR signalling augments macrophage bactericidal activity through mitochondrial ROS. Nature. 2011;472(7344):476–480. doi: 10.1038/nature09973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield G, Pears C. Superoxide signalling required for multicellular development of Dictyostelium. J Cell Sci. 2003;116(Pt 16):3387–3397. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey IS, Moran MM, Chong JA, Clapham DE. A voltage-gated proton-selective channel lacking the pore domain. Nature. 2006;440(7088):1213–1216. doi: 10.1038/nature04700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Chemaly A, Demaurex N. Do Hv1 proton channels regulate the ionic and redox homeostasis of phagosomes? Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;353(1-2):82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Chemaly A, Nunes P, Jimaja W, Castelbou C, Demaurex N. Hv1 proton channels differentially regulate the pH of neutrophil and macrophage phagosomes by sustaining the production of phagosomal ROS that inhibit the delivery of vacuolar ATPases. J Leukoc Biol. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Decoursey TE. Voltage-gated proton channels. Compr Physiol. 2012;2(2):1355–1385. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c100071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey IS, Ruchti E, Kaczmarek JS, Clapham DE. Hv1 proton channels are required for high-level NADPH oxidase-dependent superoxide production during the phagocyte respiratory burst. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(18):7642–7647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902761106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturgill-Koszycki S, et al. Lack of acidification in Mycobacterium phagosomes produced by exclusion of the vesicular proton-ATPase. Science. 1994;263(5147):678–681. doi: 10.1126/science.8303277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens DL, Lee BY, Horwitz MA. Virulent and avirulent strains of Francisella tularensis prevent acidification and maturation of their phagosomes and escape into the cytoplasm in human macrophages. Infect Immun. 2004;72(6):3204–3217. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.6.3204-3217.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alpuche-Aranda CM, Swanson JA, Loomis WP, Miller SI. Salmonella typhimurium activates virulence gene transcription within acidified macrophage phagosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(21):10079–10083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukacs GL, Rotstein OD, Grinstein S. Determinants of the phagosomal pH in macrophages. In situ assessment of vacuolar H(+)-ATPase activity, counterion conductance, and H+ 'leak'. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(36):24540–24548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K, Kagaya K, Yamada T, Fukazawa Y. Mechanism for candidacidal activity in macrophages activated by recombinant gamma interferon. Infect Immun. 1991;59(2):521–528. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.2.521-528.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip WK, et al. Phagocytosis and phagosome acidification are required for pathogen processing and MyD88-dependent responses to Staphylococcus aureus. J Immunol. 2010;184(12):7071–7081. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke M, Maddera L. Phagocyte meets prey: uptake, internalization, and killing of bacteria by Dictyostelium amoebae. Eur J Cell Biol. 2006;85(9-10):1001–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski A, Scott CC, Grinstein S. Determinants of the phagosomal pH in neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(8):6059–6066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110059200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal AW, Geisow M, Garcia R, Harper A, Miller R. The respiratory burst of phagocytic cells is associated with a rise in vacuolar pH. Nature. 1981;290(5805):406–409. doi: 10.1038/290406a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savina A, et al. NOX2 controls phagosomal pH to regulate antigen processing during crosspresentation by dendritic cells. Cell. 2006;126(1):205–218. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybicka JM, Balce DR, Chaudhuri S, Allan ER, Yates RM. Phagosomal proteolysis in dendritic cells is modulated by NADPH oxidase in a pH-independent manner. EMBO J. 2012;31(4):932–944. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantegazza AR, et al. NADPH oxidase controls phagosomal pH and antigen cross-presentation in human dendritic cells. Blood. 2008;112(12):4712–4722. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-134791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balce DR, Allan ER, McKenna N, Yates RM. gamma-Interferon-inducible lysosomal thiol reductase (GILT) maintains phagosomal proteolysis in alternatively activated macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(46):31891–31904. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.584391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanjurjo L, et al. The scavenger protein apoptosis inhibitor of macrophages (AIM) potentiates the antimicrobial response against Mycobacterium tuberculosis by enhancing autophagy. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e79670. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Z, Zhi L, Li-Juan Z, Hong-Tao X. The Utility of Chloroquine in Cancer Therapy. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015. pp. 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ohkuma S, Poole B. Fluorescence probe measurement of the intralysosomal pH in living cells and the perturbation of pH by various agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978;75(7):3327–3331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.7.3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Chemaly A, et al. VSOP/Hv1 proton channels sustain calcium entry, neutrophil migration, and superoxide production by limiting cell depolarization and acidification. J Exp Med. 2010;207(1):129–139. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine AP, Duchen MR, Segal AW. The HVCN1 channel conducts protons into the phagocytic vacuole of neutrophils to produce a physiologically alkaline pH. bioRxiv. 2014.

- Al-Fageeh MB, Smales CM. Control and regulation of the cellular responses to cold shock: the responses in yeast and mammalian systems. Biochem J. 2006;397(2):247–259. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yui N, et al. Basolateral targeting and microtubule-dependent transcytosis of the aquaporin-2 water channel. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2013;304(1):C38–C48. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00109.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths G. On phagosome individuality and membrane signalling networks. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14(7):343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poburko D, Santo-Domingo J, Demaurex N. Dynamic regulation of the mitochondrial proton gradient during cytosolic calcium elevations. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(13):11672–11684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.159962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]