Abstract

Few studies have focused on the relationship between the trajectories of long-term changes in body mass index (BMI; weight (kg)/height (m)2) and all-cause mortality in old age, particularly in non-Western populations. We evaluated this association by applying group-based mixture models to data derived from the National Survey of the Japanese Elderly, which included 4,869 adults aged 60 or more years, with up to 7 repeated observations between 1987 and 2006. Four distinct BMI trajectories were identified: “low-normal weight, decreasing” (baseline BMI = 18.7; 23.8% of sample); “mid-normal weight, decreasing” (baseline BMI = 21.9; 44.6% of sample); “high-normal weight, decreasing” (baseline BMI = 24.8; 26.5% of sample); and “overweight, stable” (baseline BMI = 28.7; 5.2% of sample). Survival analysis with an average follow-up of 13.8 years showed that trajectories of higher BMI were associated with lower mortality. In particular, relative to those with a mid-normal weight, decreasing BMI trajectory, those with an overweight, stable BMI trajectory had the lowest mortality, and those with a low-normal, decreasing BMI trajectory had the highest mortality. In sharp contrast with prior observations from Western populations, BMI changes lie primarily within the normal-weight range, and virtually no older Japanese are obese. The association between BMI trajectories and mortality varies according to the distribution of BMI within the population.

Keywords: body mass index, Japan, mortality, older adults, trajectories

Weight change is known as an important predictor of mortality risk. Although several studies have generally concluded that, in adulthood, weight loss is associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality relative to stable weight, findings on the relationship between weight gain and mortality have been mixed (1–10). These observations apply to older populations as well (1, 4, 11–15). Furthermore, in older adults, weight changes have been shown to predict mortality better than a single weight assessment (15).

Although prior studies of weight changes and mortality yield important insights, the classification of weight change could be significantly improved in 2 respects. First, weight changes in the past have been defined largely on the basis of body mass index (BMI; weight (kg)/height (m)2) measured at 2 points in time over a relatively short interval. Because body weight can fluctuate substantially over the adult life course (16–18), weight changes measured at multiple time points over an extended period of time (e.g., 5–10 or more years) may provide additional important information. Second, prior research has commonly categorized trajectories of change in BMI by using assignment rules that are based on subjective criteria (e.g., 5% gain or loss from baseline body weight). Although such assignment rules are generally reasonable, they are limited because the existence of certain categories of weight changes must be assumed a priori. Thus, the analysis cannot test empirically for their presence, which constitutes a fundamental shortcoming. In addition, ex-ante specified rules provide no basis for calibrating the precision of individual classifications to the various groups that comprise these categories. Therefore, the uncertainty about an individual's group membership cannot be quantified in the form of probabilities (19).

To date, there have been only 2 studies exploring the relationship between BMI trajectories and mortality, both of which were based on data from the Health and Retirement Study for older Americans aged 51–61 years at baseline (20, 21). However, the extent to which their conclusions can be generalized to other populations remains to be evaluated. Many non-Western societies differ significantly from the Unites States in the distribution of body weight. For instance, in Japan, 3.9% of the adult population are obese (BMI: ≥30.0), and 20.8% are overweight (BMI: 25.0–29.9), while the prevalence of underweight (BMI: <18.5) is 8.2%, and the prevalence of normal weight (BMI: 18.5–24.9) is 67.1% (22). In contrast, 27.7% and 34.9% of the US population are, respectively, obese and overweight, and 1.7% and 35.6% are underweight and normal weight (23). These differences are consistent in old-age groups (refer to detailed statistics in Web Table 1, available at http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/). Moreover, a World Health Organization Expert Consultation (24) concluded that the current World Health Organization cutoff points do not provide an adequate basis for taking action on risks related to overweight and obesity in Asian populations. This suggests the need to apply different thresholds for defining overweight and obesity in these populations. Therefore, understanding whether the trajectories of body weight changes in older Japanese and their relationships with mortality are similar or different from those observed in Western populations can carry valuable clinical and public health implications.

The present study has 2 specific aims. First, we apply group-based mixture models to identify distinct trajectories of BMI in Japanese adults, aged 60 years or more at baseline. Second, we examine the relationship between the trajectories of BMI and all-cause mortality. Our goal is to determine whether the trajectories of body weight changes in older Japanese and their relationships with mortality are similar to or different from those observed in Western populations.

METHODS

Study population

Data came from the National Survey of the Japanese Elderly, which is a 7-wave longitudinal data set that included 4,869 Japanese adults aged 60 years or more, with 16,669 observations during the period from 1987 to 2006 (an average of 3.42 observations per participant). This survey began with 2,200 respondents aged 60 years or more in 1987 (wave 1). The sample was subsequently supplemented in 1990 (wave 2; n = 580) and 1996 (wave 4; n = 1,210). An additional sample of those 70 years of age or more was added in 1999 (wave 5; n = 2,000) (for detailed information on the number of participants at each wave, refer to Web Table 2). Face-to-face interviews were used to collect data. Responses obtained from proxy interviews were excluded. Response rates for each wave of the survey ranged from 67% to 93%. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology and the University of Michigan.

Mortality and follow-up

Follow-ups for all-cause mortality were conducted until December 31, 2012. Participants' dropout from the study or dates of death were collected by reviewing residence certificates with the permission of local municipalities where the participants lived. For people whose date of death (year, month, and day) could not be ascertained (n = 35), a date was imputed as the midpoint between the respondent's last interview and the next wave. If only month or day of death could not be obtained (n = 363), a date was imputed as the midpoint of the year or the month of death. Consequently, 54.0% (n = 2,628) died during the follow-up period. Those who had refused the interview survey were treated as censored (6.0%; n = 291). A total follow-up period was 25 years (13.8 years of average follow-up per participant).

Measures

Height and weight were self-reported at each wave (waves 1–7), and BMI was calculated from these self-reported values according to accepted formula as specified above. Age, sex, marital status, current working status, education, annual household income, health behaviors, and health status at baseline were incorporated as covariates in the present study. Health behaviors included the number of cigarettes smoked per day, the number of drinking days per month, and frequency of exercise.

Health status was measured by chronic diseases, self-rated health, and functional status. The number of physician-diagnosed chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease, stroke, lung disease, liver disease, and kidney disease, was reported by the respondents. Self-rated poor health was measured by a 3-item composite with a score ranging from 3 to 15 (Cronbach's α = 0.84); a high score indicates poor health. Finally, functional status entailed a sum of difficulties with 6 activities of daily living (ADLs) (i.e., dressing, walking, bathing or showering, eating, getting in or out of bed, and using the toilet) and 5 instrumental ADLs (i.e., grocery shopping, phone calls, climbing stairs, walking a few blocks, and traveling by bus or train). All items were scored by either a 4- or 5-point scale. With appropriate adjustment, scores for this composite ranged from 11.5 to 55 (Cronbach's α = 0.92); a high score reflects greater functional disability. The measure for ADLs in 1987 (wave 1) consisted of only1 item (i.e., bathing or showering), whereas ADLs were measured by 6 items at the subsequent waves (1990–2006; waves 2–7). To homogenize the 1-item ADL measure collected in 1987 with the 6-item ADLs measure taken after 1987, we imputed the values of the 6-item ADLs measure for those who had only 1-item ADL available in 1987 (n = 2,200). This is justified in view of the fact that the 1-item ADL measure is highly correlated with the 6-item ADLs measure (r = 0.92).

Statistical analysis

We used group-based mixture models with maximum likelihood estimation to identify distinct trajectories of changes in BMI (25). As recommended, the best-fitting model (i.e., the number of distinct trajectories) was chosen on the basis of Bayesian Information Criterion scores and an examination of 95% confidence intervals (19). We estimated models with 2–5 trajectories by assuming linear, quadratic, and cubic patterns of change in BMI over time, using the SAS PROC TRAJ program (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina). We selected the best-fitting model by comparing the Bayesian Information Criterion indices associated with various solutions and the average posterior probabilities of group membership, and by evaluating whether successive models identified additional distinct groups as indicated by nonoverlapping confidence intervals.

In this study, the time from baseline was used as the time scale because different birth cohorts were observed at different ages; thus, cohort and age effects were highly confounded. Moreover, the time-based approach seems to best capture our interest in describing distinct patterns of change in BMI over time among Japanese older adults from different birth cohorts.

In a subsequent step, indicators of trajectory membership were included as predictors of mortality in a Cox proportional hazard model in order to calculate the relative mortality risk of each trajectory. To control for possible effects of precipitated weight loss prior to death on baseline BMI, we undertook additional analyses excluding people whose death occurred within a year from baseline. Furthermore, to rule out the confounding effects of smoking, physical activity, and chronic diseases on BMI and mortality, we conducted parallel analyses of selected subgroups: noncurrent smokers, physically active individuals, and those without a history of cardiovascular disease, stroke, lung disease, liver disease, and kidney disease. The results were expressed as hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals. The analyses were performed by using the SAS PROC PHREG program (SAS Institute, Inc.).

Initial descriptive analysis of the individual variables in this study indicated that, with the exception of household income with 35.3% missing data, the proportion of cases with missing data on the remaining items ranged from 0% to 8.6%. Although PROC TRAJ assumes a missing-at-random mechanism, this is not the case for the Cox regression analysis. Without imputation, it may lead to a serious loss of cases in the Cox regression analysis. To minimize the potential bias associated with item nonresponse, we used multiple imputation for missing data (26), by using an inclusive strategy with not only variables included in our analytical models but also auxiliary variables not included in our analysis (27). Examples of auxiliary variables included social support, depressive symptoms, and follow-up measures of the predictors in the Cox regression analysis, which were measured at baseline. In particular, 3 complete data sets were imputed with NORM freeware (available from Springer International Publishing AG, Cham, Switzerkand), and analyses were run on each of these 3 data sets with parameter estimates derived by averaging across 3 imputations and by adjusting for their variance. The imputation procedure was performed for surviving participants temporally by removing participants after death. Both group-based mixture models and the Cox proportional hazard model were conducted by using the imputed data sets.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the sample descriptive characteristics at baseline. Mean age was 69.9 years, and 55.3% were female. Mean BMI was 22.3, with 10.7% underweight, 71.4% in the normal range, 16.4% overweight, and 1.4% obese.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants (n = 4,869), National Survey of the Japanese Elderly, 1987, 1990, 1996, and 1999

| Characteristic | Nonimputation |

Imputation |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | % | Mean (SD) | % | |

| Age | ||||

| Years | 69.9 (7.2) | 69.9 (7.2) | ||

| Missing | 0.0 | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 55.3 | 55.3 | ||

| Missing | 0.0 | |||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 67.0 | 67.1 | ||

| Missing | 0.0 | |||

| Employment | ||||

| Currently working | 31.6 | 31.6 | ||

| Missing | 0.0 | |||

| Education | ||||

| Years | 9.2 (2.8) | 9.2 (2.8) | ||

| Missing | 1.0 | |||

| Annual household income, million yen | ||||

| <1.2 | 6.7 | 10.4 | ||

| 1.2–2.9 | 19.2 | 29.0 | ||

| 3.0–4.9 | 18.2 | 30.5 | ||

| 5.0–9.9 | 15.0 | 22.4 | ||

| ≥10 | 5.5 | 7.6 | ||

| Missing | 35.3 | |||

| Average no. of cigarettes smoked per day | ||||

| 0 | 75.5 | 75.5 | ||

| 1–19 | 12.4 | 12.4 | ||

| ≥20 | 12.1 | 12.1 | ||

| Missing | 0.1 | |||

| Average no. of drinking days per month | ||||

| 0 | 59.7 | 59.7 | ||

| 1–15 | 13.6 | 14.2 | ||

| 16–25 | 3.9 | 4.9 | ||

| ≥26 | 20.7 | 21.2 | ||

| Missing | 2.1 | |||

| Frequency of exercise | ||||

| Often/sometimes | 47.8 | 48.0 | ||

| Rarely/none | 51.9 | 52.0 | ||

| Missing | 0.3 | |||

| Chronic diseases | ||||

| Cardiovascular disease | ||||

| Participants with condition | 10.9 | 11.0 | ||

| Missing | 0.6 | |||

| Stroke | ||||

| Participants with condition | 2.9 | 2.9 | ||

| Missing | 0.8 | |||

| Lung disease | ||||

| Participants with condition | 4.8 | 4.9 | ||

| Missing | 0.8 | |||

| Liver disease | ||||

| Participants with condition | 3.5 | 3.6 | ||

| Missing | 0.8 | |||

| Kidney disease | ||||

| Participants with condition | 2.2 | 2.2 | ||

| Missing | 0.7 | |||

| None of these diseases | ||||

| Participants with condition | 78.4 | 79.4 | ||

| Missing | 1.6 | |||

| Self-rated health | ||||

| Score | 7.7 (2.8) | 7.7 (2.8) | ||

| Missing | 2.7 | |||

| Functional status | ||||

| Score | 12.5 (4.2) | 12.6 (3.8) | ||

| Missing | 1.3 | |||

| Entry wave | ||||

| Wave 1 (year 1987) | 45.2 | 45.2 | ||

| Wave 2 (year 1990) | 7.5 | 7.5 | ||

| Wave 4 (year 1996) | 18.4 | 18.4 | ||

| Wave 5 (year 1999) | 28.9 | 28.9 | ||

| Missing | 0.0 | |||

| Body mass indexa | 22.4 (3.2) | 22.3 (3.2) | ||

| <18.5 | 8.8 | 10.7 | ||

| 18.5–24.9 | 65.1 | 71.4 | ||

| 25.0–29.9 | 15.4 | 16.4 | ||

| ≥30.0 | 1.5 | 1.4 | ||

| Missing | 9.3 | |||

| Height | ||||

| Measure, cm | 155.5 (8.5) | 155.0 (8.6) | ||

| Missing | 8.6 | |||

| Weight | ||||

| Measure, kg | 53.8 (9.3) | 53.6 (9.3) | ||

| Missing | 3.4 | |||

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

a Weight (kg)/height (m)2.

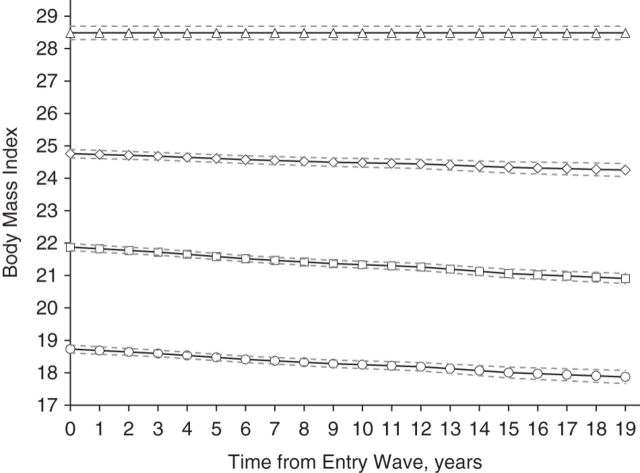

Figure 1 illustrates the BMI trajectories derived from group-based mixture models, whereas Table 2 shows the intercept and linear slope of each trajectory. As the patterns of the trajectories from each imputed data set were similar, we show the trajectory patterns from only 1 of the 3 imputed data sets on Figure 1. In particular, 4 distinct trajectories were identified: “low-normal weight, decreasing” (baseline BMI =18.7, 95% confidence interval (CI): 18.6, 18.9; 23.8% of sample); “mid-normal weight, decreasing” (baseline BMI =21.9, 95% CI: 21.8, 22.0; 44.6% of sample); “high-normal weight, decreasing” (baseline BMI = 24.8, 95% CI: 24.7, 25.0; 26.5% of sample); and “overweight, stable” (baseline BMI = 28.7, 95% CI: 28.5, 28.9; 5.2% of sample). This model was identified as the best-fitting model based on the Bayesian Information Criterion, which revealed an improved model fit from 2 to 4 trajectories, with little improvement beyond 4 trajectories. In addition, the model with 4 trajectories had a better fit than that with 5 trajectories.

Figure 1.

Body mass index trajectories for the 4-group model over 19 years, National Survey of the Japanese Elderly, 1987–2006. Solid lines indicate the mean values of body mass index (weight (kg)/height (m)2) for members in the groups; dashed lines, 95% confidence intervals. The trajectories are as follows: circles, low-normal weight, decreasing; squares, mid-normal weight, decreasing; diamonds, high-normal weight, decreasing; and triangles, overweight, stable.

Table 2.

Estimates of Growth Curve Parameters for Body Mass Index Trajectories, National Survey of the Japanese Elderly, 1987–2006

| Body Mass Index Trajectory |

Parameter |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept, kg/m2 |

Linear Slope, kg/m2 |

Group Membership, % |

Average Group Probabilitya | |||

| Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | |||

| Low-normal weight, decreasing | 18.7 | 18.6, 18.9 | −0.05 | −0.06, −0.03 | 23.8 | 0.873 |

| Mid-normal weight, decreasing | 21.9 | 21.8, 22.0 | −0.05 | −0.06, −0.04 | 44.6 | 0.841 |

| High-normal weight, decreasing | 24.8 | 24.7, 25.0 | −0.03 | −0.04, −0.01 | 26.5 | 0.860 |

| Overweight, stable | 28.7 | 28.5, 28.9 | 5.2 | 0.893 | ||

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

a Average group probability indicates the posterior probability of membership among the cases in each trajectory group.

We also estimated a series of trajectories by assuming quadratic and cubic patterns of change in BMI over time. Comparing the fit indices of the different estimated models, we concluded that the 4 linear trajectories provided the optimal fit to the data. Although the quadratic functions of these trajectories were statistically significant, the quadratic coefficients for the 3 declining trajectories were very small. Moreover, the Bayesian Information Criterion index for the quadratic models was almost identical to that for the linear models (−38,250.12 vs. −38,253.28). Thus, we chose the linear models in presenting our results. For reference, the quadratic pattern of BMI trajectories for the 4-group model is provided as Web Figure 1.

As there is a debate regarding the relative merits of random imputation of missing values, particularly those of the dependent variable, we undertook PROC TRAJ by using the imputed data as well as the nonimputed data (refer to Web Table 3 (estimations of growth curve parameters) and Web Figure 2 (illustration of BMI trajectories)). Because the results based on the imputed data and nonimputed data were quite similar, we have chosen to present the results based on the imputed data.

Table 3 presents the baseline characteristics of the 4 trajectory subgroups. The subgroup following the “low-normal weight, decreasing” trajectory had the highest mean age among the 4 subgroups; approximately 70% in the “overweight, stable” subgroup and roughly 50% in the “mid-normal weight, decreasing” subgroup were female.

Table 3.

Baseline Characteristics by the Subgroups of Body Mass Index Trajectories, National Survey of the Japanese Elderly, 1987, 1990, 1996, and 1999

| Characteristic | Low-Normal Weight, Decreasing |

Mid-Normal Weight, Decreasing |

High-Normal Weight, Decreasing |

Overweight, Stable |

P Valuea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD)b | %b | Mean (SD)b | %b | Mean (SD)b | %b | Mean (SD)b | %b | ||

| Age, years | 72.1 (7.5) | 69.8 (7.2) | 68.3 (6.5) | 68.1 (6.5) | <0.001c | ||||

| Female | 55.6 | 51.3 | 59.2 | 70.5 | <0.001d | ||||

| Married | 61.8 | 67.2 | 70.9 | 70.5 | 0.039d | ||||

| Currently working | 25.9 | 32.5 | 33.7 | 40.1 | 0.006d | ||||

| Education, years | 9.0 (2.8) | 9.2 (2.7) | 9.3 (2.8) | 9.0 (2.7) | 0.887c | ||||

| Annual household income, million yen | <0.001c | ||||||||

| <1.2 | 14.0 | 9.6 | 9.1 | 8.4 | |||||

| 1.2–2.9 | 30.3 | 28.8 | 28.7 | 26.7 | |||||

| 3.0–4.9 | 31.2 | 30.6 | 29.7 | 30.9 | |||||

| 5.0–9.9 | 19.5 | 23.3 | 23.2 | 24.4 | |||||

| ≥10 | 5.0 | 7.7 | 9.3 | 9.6 | |||||

| Average no. of cigarettes smoked per day | <0.001c | ||||||||

| 0 | 71.5 | 72.5 | 82.4 | 85.4 | |||||

| 1–19 | 15.8 | 13.7 | 8.0 | 7.9 | |||||

| ≥20 | 12.7 | 13.8 | 9.6 | 6.7 | |||||

| Average no. of drinking days per month | 0.100c | ||||||||

| 0 | 62.3 | 57.3 | 60.3 | 66.9 | |||||

| 1–15 | 11.8 | 14.4 | 16.1 | 13.9 | |||||

| 16–25 | 4.4 | 5.0 | 5.1 | 5.0 | |||||

| ≥26 | 21.5 | 23.3 | 18.5 | 14.2 | |||||

| Frequency of exercise | 0.004d | ||||||||

| Often/sometimes | 42.6 | 49.4 | 50.2 | 47.6 | |||||

| Rarely/none | 57.4 | 50.6 | 49.8 | 52.4 | |||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 11.1 | 10.0 | 12.1 | 14.3 | 0.009d | ||||

| Stroke | 2.9 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 2.4 | 0.506d | ||||

| Lung disease | 5.6 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 6.4 | 0.126d | ||||

| Liver disease | 3.6 | 3.7 | 3.2 | 4.0 | 0.576d | ||||

| Kidney disease | 2.6 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 2.9 | 0.565d | ||||

| None of these diseases | 78.8 | 80.5 | 79.1 | 73.5 | 0.006d | ||||

| Self-rated health, score | 8.1 (3.0) | 7.5 (2.7) | 7.6 (2.8) | 8.1 (2.9) | 0.114c | ||||

| Functional status, score | 13.1 (4.8) | 12.4 (3.4) | 12.3 (3.3) | 12.8 (4.1) | 0.520c | ||||

| Entry wave | <0.001e | ||||||||

| Wave 1 (year 1987) | 54.0 | 44.2 | 40.6 | 37.1 | |||||

| Wave 2 (year 1990) | 5.9 | 7.6 | 9.0 | 6.1 | |||||

| Wave 4 (year 1996) | 10.8 | 19.1 | 22.4 | 27.4 | |||||

| Wave 5 (year 1999) | 29.3 | 29.1 | 28.0 | 29.4 | |||||

| Body mass indexf | 18.6 (1.7) | 21.9 (1.8) | 24.9 (1.7) | 29.0 (2.9) | <0.001c | ||||

| Height, cm | 154.7 (8.8) | 155.5 (8.5) | 154.9 (8.4) | 152.8 (9.3) | 0.206c | ||||

| Weight, kg | 44.6 (6.2) | 53.0 (6.8) | 60.0 (7.3) | 67.6 (9.1) | <0.001c | ||||

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

a P values were adjusted for age and sex (2 sided). P values for age and sex were adjusted by sex and age, respectively.

b Mean (SD) and % are calculated from the imputed data sets.

c Analysis of covariance.

d Wald test for the logistic regression model.

e Likelihood ratio test for the multinomial logistic regression model.

f Weight (kg)/height (m)2.

Table 4 shows the mortality hazard ratios for each BMI trajectory subgroup, with the “mid-normal weight, decreasing” trajectory subgroup as reference. In model 1, after adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics, health behaviors, health status at baseline, and entry wave, the “low-normal weight, decreasing” subgroup had a significantly higher mortality risk compared with the “mid-normal weight, decreasing” subgroup (hazard ratio = 1.17, 95% CI: 1.02, 1.33). On the other hand, the “high-normal weight, decreasing” (hazard ratio = 0.82, 95% CI: 0.72, 0.93) and “overweight, stable” (hazard ratio = 0.72, 95% CI: 0.54, 0.96) subgroups had significantly lower risks of death. Excluding events occurring within 1 year from baseline produced no change in the associations described in model 1 (model 2a). In the subgroup analyses of noncurrent smokers and physically active individuals (models 2b and 2c), the associations of “low-normal weight, decreasing” and “overweight, stable” with mortality were attenuated and became nonsignificant among noncurrent smokers, while the linkage between “low-normal weight, decreasing” and mortality became more pronounced among physically active individuals. Finally, the analysis of those without any major disease at baseline did not substantially alter the risk estimations (model 2d). For reference, Web Table 4 provides the hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals of both strata in models 2b–2d.

Table 4.

Association Between Body Mass Index Trajectories and All-Cause Mortality, National Survey of the Japanese Elderly, 1987–2006

| Body Mass Index Trajectories | Death Before December 31, 2012, % | Model 0a (n = 4,869) |

Model 1b (n = 4,869) |

Model 2ac (n = 4,792) |

Model 2bd (n = 3,674) |

Model 2ce (n = 2,336) |

Model 2df (n = 3,868) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | ||

| Low-normal weight, decreasing | 67.6 | 1.38 | 1.26, 1.52 | 1.17 | 1.02, 1.33 | 1.17 | 1.02, 1.35 | 1.06 | 0.94, 1.21 | 1.30 | 1.09, 1.57 | 1.18 | 1.01, 1.38 |

| Mid-normal weight, decreasing | 54.9 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| High-normal weight, decreasing | 43.1 | 0.70 | 0.64, 0.78 | 0.82 | 0.72, 0.93 | 0.82 | 0.73, 0.93 | 0.82 | 0.69, 0.96 | 0.85 | 0.70, 1.02 | 0.80 | 0.70, 0.93 |

| Overweight, stable | 38.4 | 0.61 | 0.48, 0.76 | 0.72 | 0.54, 0.96 | 0.73 | 0.55, 0.98 | 0.84 | 0.57, 1.22 | 0.75 | 0.48, 1.19 | 0.69 | 0.47, 1.01 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

a Unadjusted model.

b Fully adjusted model: adjusted for age; sex; marital status; currently working; education; annual household income; weight (kg); number of cigarettes smoked per day; number of drinking days per month; frequency of exercise; history of cardiovascular disease, stroke, lung disease, liver disease, and kidney disease; self-rated health and functional status at baseline; and entry wave.

c Excluding people who died within 1 year after baseline: adjusted for age; sex; marital status; currently working; education; annual household income; weight (kg); number of cigarettes smoked per day; number of drinking days per month; frequency of exercise; history of cardiovascular disease, stroke, lung disease, liver disease, and kidney disease; self-rated health and functional status at baseline; and entry wave.

d Noncurrent smokers: adjusted for age; sex; marital status; currently working; education; annual household income; weight (kg); number of drinking days per month; frequency of exercise; history of cardiovascular disease, stroke, lung disease, liver disease, and kidney disease; self-rated health and functional status at baseline; and entry wave.

e Physically active individuals (often/sometimes): adjusted for age; sex; marital status; currently working; education; annual household income; weight (kg); number of cigarettes smoked per day; number of drinking days per month; history of cardiovascular disease, stroke, lung disease, liver disease, and kidney disease; self-rated health and functional status at baseline; and entry wave.

f Those without a history of cardiovascular disease, stroke, lung disease, liver disease, and kidney disease: adjusted for age; sex; marital status; currently working; education; annual household income; weight (kg); number of cigarettes smoked per day; number of drinking days per month; frequency of exercise; self-rated health and functional status at baseline; and entry wave.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the heterogeneity of BMI trajectories and its relationship with old age mortality in an Asian population. In particular, we found 4 distinct BMI trajectories over a period of 19 years among older Japanese. Three of them had a baseline BMI within a normal range (i.e., low-, mid-, and high-normal weight) that decreased over time. The fourth trajectory started at a level of overweight and remained unchanged over time. Our research provides new evidence that the trajectories of BMI and their linkages with mortality differ between Western and Asian populations.

The findings are quite striking in view of earlier observations on BMI trajectories in middle and old age based on US data (20, 21, 28–30). Specifically, among middle-aged and older Americans, trajectories of overweight and obesity often account for 70%–80% of the sample, whereas a little over 5% of older Japanese in our analysis were identified as following a stable overweight trajectory. Furthermore, among older Japanese, BMI changes primarily lie within the normal-weight range (i.e., BMI: 18.5–25.0), although approximately 24% of older Japanese followed a trajectory of “low-normal weight, decreasing” that started with a BMI of 18.7 and decreased to 17.8 over 19 years. Therefore, older Japanese differ from older Americans not only in terms of the weight distribution at a single point in time but also in the patterns of weight changes over time. Of the 4 BMI trajectories identified among older Japanese, those characterized by higher body-weight levels were associated with lower mortality. The “low-normal weight, decreasing” subgroup had the highest mortality risk, followed by the “mid-normal weight, decreasing,” the “high-normal weight, decreasing,” and the “overweight, stable” subgroups. This is consistent with prior observations showing that weight loss in underweight individuals is associated with an increased mortality risk than in normal-weight or overweight/obese individuals (1, 9, 14). Decreasing body weight is often accompanied by an accumulation of muscle or bone loss (31, 32). This might represent a reduced ability to maintain energy balance, which shares many immunological and neuroendocrine features of disease-associated wasting syndromes (33).

Over the period of our observation, changes in BMI were relatively small, and these trajectories were relatively parallel. In contrast to the general population, older populations tend to have a reverse J-shaped or L-shaped association of BMI with all-cause mortality (34–36), which was also found in Japanese studies (37–39). These studies report that underweight is an important predictor of mortality, while overweight has the lowest mortality risk in old age. This has been referred to as the “obesity paradox” (40). This might be due to energy and nutritional reserves, as malnutrition is known to be a predictor of all-cause mortality (41, 42). Thin people with less energy and nutritional reserves are less resistant to infection (43). In fact, thinness is associated with a higher risk of respiratory disease than is normal weight among older Japanese (38). In addition, there is some evidence that stable overweight is associated with a low risk of death (1, 8, 10). Extra body weight may provide protection against nutritional and energy deficiencies and the loss of muscle and bone.

Therefore, it would be reasonable to conclude that the subgroup with low-normal but decreasing weight had the highest mortality risk, while the subgroup with stable overweight had the lowest mortality risk among the 4 trajectory subgroups. There have been only 2 US studies to date examining the linkages between BMI trajectories and mortality in old age (20, 21), both of which suggested that those who were overweight but stable had the highest survival rate. This is consistent with our findings from this Japanese population. More importantly, according to our results, even a small or moderate weight loss among those with a normal BMI may have a deleterious effect on health. Hence, both BMI at baseline and its changes over time are important in predicting the risk of death. Accordingly, for older Japanese, a greater clinical and public health emphasis should be placed on preventing weight loss, rather than on combating overweight and obesity.

Among noncurrent smokers in model 2b, the association between BMI trajectories and mortality became nonsignificant. This suggests an effect modification of smoking on the association. Smoking is known to be associated with a lower BMI trajectory in old age (44) and to reduce life expectancy (45). Our findings revealed that the association between BMI trajectories and mortality existed among noncurrent smokers only.

A major strength of this research lies in its longitudinal data derived from a national probability sample of older Japanese over a 19-year period. Many previous studies used an a priori categorization of the levels and changes in BMI and examined its relationship with mortality. We applied a person-centered approach (19), which provided a strong empirical support to identify distinct BMI trajectories in older Japanese and to assess differences in mortality risk between these trajectories. Our research yields important new information regarding the trajectories of BMI among older Japanese and how they are associated with mortality, and it suggests that priorities for weight control in old age may well differ between Japan and the United States.

The present study has several limitations. First, BMI was calculated from self-reported measures of height and weight. As people tend to overreport their height and underreport their weight (46–48) and heavier people tend to underreport their weight more than thinner people (46), the BMI may have been underestimated, particularly among overweight individuals. This could bias the estimated pattern of BMI trajectories. Meanwhile, as there is a possibility that people underestimate their current weight due to the factors related to mortality (e.g., chronic disease progression), the findings of this study should be carefully interpreted. Second, our approach to model change in BMI by time since baseline in group-based mixture models fails to distinguish between age effects and period effects (49). Although we understand the pitfalls of this approach, the alternative age-based approach fails to distinguish between age effects and cohort effects (49). We favored the time-based approach because it seems to best capture our interest in describing distinct patterns of change in BMI over time among Japanese older adults that could then be used to predict mortality. Moreover, in the mortality analysis, we adjusted for baseline age and entry wave. Third, we did not distinguish between intentional and unintentional weight changes. Several studies have reported that, for equivalent amounts of weight loss, unintentional loss was associated with a higher mortality risk compared with intentional loss (50–52). By differentiating between these 2 types of weight change, we believe that a better understanding of the factors underlying the association between BMI trajectories and mortality may emerge. Nonetheless, we adjusted for baseline health status that may partially account for unintentional weight loss. Fourth, there is the possibility that diseases other than the 5 diseases we adjusted for in the analysis confound the association between body weight and mortality. History of cancer is a possible confounding factor but was not included in the calculation of the health status variable because this question was not included in wave 1. This was because, in the 1980s Japanese culture, physicians were often reluctant to inform a patient of a diagnosis of cancer (53). We undertook a sensitivity analysis by running the same survival analyses, including an imputed variable of history of cancer in the model, and obtained results similar to those reported in this study.

In conclusion, this research provides new insights concerning the complex dynamic linkages between BMI and mortality in old age in Japan. In contrast with prior observations made in Western populations, our research identified a downward trajectory at the border between normal weight and underweight subgroups, which characterized a significant proportion of older Japanese (i.e., the “low-normal weight, decreasing” subgroup). This trajectory was associated with the highest risk of mortality among the 4 trajectories identified in this study. At the same time, we found a trajectory of stable overweight that characterized a small proportion of older Japanese who had the lowest risk of death, which is similar to the results described earlier in Western populations (20, 21). Our research suggests that, in later life, a trajectory of low and declining BMI poses a significant risk for survival; this finding could inform clinical and public health approaches to body-weight management aimed to improve the health and survival of older adults, particularly in Asian populations.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Author affiliations: Department of Health Management and Policy, University of Michigan School of Public Health, Ann Arbor, Michigan (Hiroshi Murayama, Jersey Liang, Joan M. Bennett); Research Team for Social Participation and Community Health, Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology, Tokyo, Japan (Hiroshi Murayama, Erika Kobayashi, Taro Fukaya, Shoji Shinkai); Department of Health Policy, Management, and Behavior, School of Public Health, State University of New York at Albany, Rensselaer, New York (Benjamin A. Shaw); Department of Behavioral Sciences, University of Michigan–Dearborn, Dearborn, Michigan (Anda Botoseneanu); and Department of Internal Medicine/Geriatrics, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut (Anda Botoseneanu).

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (grant R01 AG031109) and the National Institutes of Health (grant P60 AG024824).

Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Corrada MM, Kawas CH, Mozaffar F, et al. Association of body mass index and weight change with all-cause mortality in the elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;16310:938–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drøyvold WB, Lund Nilsen TI, Lydersen S, et al. Weight change and mortality: the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study. J Intern Med. 2005;2574:338–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maru S, van der Schouw YT, Gimbrère CH, et al. Body mass index and short-term weight change in relation to mortality in Dutch women after age 50 y. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;801:231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nanri A, Mizoue T, Takahashi Y, et al. Weight change and all-cause, cancer and cardiovascular disease mortality in Japanese men and women: the Japan Public Health Center-Based Prospective Study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2010;342:348–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saito I, Konishi M, Iso H, et al. Impact of weight change on specific-cause mortality among middle-aged Japanese individuals. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;636:447–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sauvaget C, Ramadas K, Thomas G, et al. Body mass index, weight change and mortality risk in a prospective study in India. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;375:990–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Walker M. Weight change, weight fluctuation, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2002;16222:2575–2580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mikkelsen KL, Heitmann BL, Keiding N, et al. Independent effects of stable and changing body weight on total mortality. Epidemiology. 1999;106:671–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nilsson PM, Nilsson JA, Hedblad B, et al. The enigma of increased non-cancer mortality after weight loss in healthy men who are overweight or obese. J Intern Med. 2002;2521:70–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klenk J, Rapp K, Ulmer H, et al. Changes of body mass index in relation to mortality: results of a cohort of 42,099 adults. PLoS One. 2014;91:e84817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amador LF, Al Snih S, Markides KS, et al. Weight change and mortality among older Mexican Americans. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2006;183:196–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dey DK, Rothenberg E, Sundh V, et al. Body mass index, weight change and mortality in the elderly. A 15 y longitudinal population study of 70 y olds. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2001;556:482–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newman AB, Yanez D, Harris T, et al. Weight change in old age and its association with mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;4910:1309–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Myrskylä M, Chang VW. Weight change, initial BMI, and mortality among middle- and older-aged adults. Epidemiology. 2009;206:840–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Somes GW, Kritchevsky SB, Shorr RI, et al. Body mass index, weight change, and death in older adults: the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;1562:132–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clarke P, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD, et al. Social disparities in BMI trajectories across adulthood by gender, race/ethnicity and lifetime socio-economic position: 1986–2004. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;382:499–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuemmeler BF, Yang C, Costanzo P, et al. Parenting styles and body mass index trajectories from adolescence to adulthood. Health Psychol. 2012;314:441–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Botoseneanu A, Liang J. Social stratification of body weight trajectory in middle-age and older Americans: results from a 14-year longitudinal study. J Aging Health. 2011;233:454–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagin DS. Group-based Modeling of Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zajacova A, Ailshire J. Body mass trajectories and mortality among older adults: a joint growth mixture-discrete-time survival analysis. Gerontologist. 2014;542:221–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng H, Tumin D, Qian Z. Obesity and mortality risk: new findings from body mass index trajectories. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;17811:1591–1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare. The National Health and Nutrition Survey in Japan, 2011. Tokyo, Japan: Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schoenborn CA, Adams PF, Peregoy JA. Health behaviors of adults: United States, 2008–2010. Vital Health Stat. 2013;10257:60–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;3639403:157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones BL, Nagin DS, Roeder K. A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociol Methods Res. 2001;293:374–393. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schafer JL. Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data. London, United Kingdom: Chapman & Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Enders CK. Applied Missing Data Analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Botoseneanu A, Liang J. Latent heterogeneity in long-term trajectories of body mass index in older adults. J Aging Health. 2013;252:342–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chiu CJ, Wray LA, Lu FH, et al. BMI change patterns and disability development of middle-aged adults with diabetes: a dual trajectory modeling approach. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;289:1150–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuchibhatla MN, Fillenbaum GG, Kraus WE, et al. Trajectory classes of body mass index in a representative elderly community sample. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;686:699–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abe T, Sakamaki M, Yasuda T, et al. Age-related, site-specific muscle loss in 1507 Japanese men and women aged 20 to 95 years. J Sports Sci Med. 2011;101:145–150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Visser M. Epidemiology of muscle mass loss with age. In: Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Morley JE, eds. Sarcopenia. Oxford, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons; 2012:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwartz MW, Seeley RJ. Seminars in medicine of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Neuroendocrine responses to starvation and weight loss. N Engl J Med. 1997;33625:1802–1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flicker L, McCaul KA, Hankey GJ, et al. Body mass index and survival in men and women aged 70 to 75. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;582:234–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grabowski DC, Ellis JE. High body mass index does not predict mortality in older people: analysis of the Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;497:968–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sergi G, Perissinotto E, Pisent C, et al. An adequate threshold for body mass index to detect underweight condition in elderly persons: the Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging (ILSA). J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;607:866–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Inoue K, Shono T, Toyokawa S, et al. Body mass index as a predictor of mortality in community-dwelling seniors. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2006;183:205–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takata Y, Ansai T, Soh I, et al. Body mass index and disease-specific mortality in an 80-year-old population at the 12-year follow-up. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;571:46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tamakoshi A, Yatsuya H, Lin Y, et al. BMI and all-cause mortality among Japanese older adults: findings from the Japan Collaborative Cohort Study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2010;182:362–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oreopoulos A, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Sharma AM, et al. The obesity paradox in the elderly: potential mechanisms and clinical implications. Clin Geriatr Med. 2009;254:643–659, viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Correia MI, Waitzberg DL. The impact of malnutrition on morbidity, mortality, length of hospital stay and costs evaluated through a multivariate model analysis. Clin Nutr. 2003;223:235–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sahyoun NR, Jacques PF, Dallal G, et al. Use of albumin as a predictor of mortality in community dwelling and institutionalized elderly populations. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;499:981–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chandra RK. Nutrition and the immune system: an introduction. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;662:460S–463S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Botoseneanu A, Liang J. The effect of stability and change in health behaviors on trajectories of body mass index in older Americans: a 14-year longitudinal study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;6710:1075–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ozasa K, Katanoda K, Tamakoshi A, et al. Reduced life expectancy due to smoking in large-scale cohort studies in Japan. J Epidemiol. 2008;183:111–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nawaz H, Chan W, Abdulrahman M, et al. Self-reported weight and height: implications for obesity research. Am J Prev Med. 2001;204:294–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gunnell D, Berney L, Holland P, et al. How accurately are height, weight and leg length reported by the elderly, and how closely are they related to measurements recorded in childhood? Int J Epidemiol. 2000;293:456–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakamura K, Hoshino Y, Kodama K, et al. Reliability of self-reported body height and weight of adult Japanese women. J Biosoc Sci. 1999;314:555–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mendes de Leon CF. Aging and the elapse of time: a comment on the analysis of change. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;623:S198–S202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Lennon L. Reasons for intentional weight loss, unintentional weight loss, and mortality in older men. Arch Intern Med. 2005;1659:1035–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gregg EW, Gerzoff RB, Thompson TJ, et al. Intentional weight loss and death in overweight and obese U.S. adults 35 years of age and older. Ann Intern Med. 2003;1385:383–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sørensen TI, Rissanen A, Korkeila M, et al. Intention to lose weight, weight changes, and 18-y mortality in overweight individuals without co-morbidities. PLoS Med. 2005;26:e171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Uchitomi Y, Yamawaki S. Truth-telling practice in cancer care in Japan. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;809:290–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.