Abstract

An increasingly reported entity, Lemierre's syndrome classically presents with a recent oropharyngeal infection, internal jugular vein thrombosis and the presence of anaerobic organisms such as Fusobacterium necrophorum. The authors report a normally fit and well 17-year-old boy who presented with severe sepsis following a 5-day history of a sore throat, myalgia and neck stiffness requiring intensive care admission. Blood cultures grew F. necrophorum and radiological investigations demonstrated left internal jugular vein, cavernous sinus and sigmoid sinus thrombus, left vertebral artery dissection and thrombus within the left internal carotid artery. Imaging also revealed two areas of acute ischaemia in the brain, consistent with septic emboli, skull base (clival) osteomyelitis and an extensive epidural abscess. The patient improved on meropenem and metronidazole and was warfarinised for his cavernous sinus thrombosis. He has an on-going left-sided hypoglossal (XIIth) nerve palsy.

Background

Lemierre’s syndrome is a complication postoropharyngeal infection most commonly caused by Fusobacterium necrophorum. It is characterised by local invasion of surrounding head and neck structures, and internal jugular vein thrombosis, followed by distant metastasis from septic emboli. The importance of early recognition of Lemierre’s syndrome is increasing as there has been resurgence in recent years coinciding with reduction of routine antibiotic use in sore throats.1 Early and aggressive treatment is paramount in reducing mortality and morbidity.

The disease course can be highly varied due to a constellation of possible complications. Pulmonary manifestations are by far the commonest, documented to be as high as 79.8%. These include septic pulmonary embolisms with cavitating pneumonia and pleural effusions.2 Septic arthritis of large joints is also common (16.5%) and extensive vertebral osteomyelitis has been documented.3 Jugular vein thrombosis can extend to involve the cavernous and sigmoid sinuses. Vertebral and carotid arteries, albeit rarer, can be thrombosed and dissected.4 5

Complications of the central nervous system are far less common. We report a patient with F. necrophorum isolated in blood cultures and radiological evidence of the rarer complications of Lemierre's syndrome, including extensive vein thrombosis requiring warfarinisation, vertebral artery dissection and thrombosis, and clival osteomyelitis leading to a XIIth nerve palsy.

Case presentation

A 17-year-old Caucasian boy presented to accident and emergency (A+E) with a 5-day history of a sore throat, generalised myalgia and persistent vomiting. On arrival, he was septic and haemodynamically compromised. The patient was feverish at 39.9°C, hypotensive (blood pressure 77/44), tachycardic (heart rate 120) and tachypnoeic (respiratory rate 28).

Respiratory and cardiovascular examinations were unremarkable. Abdominal examination revealed minimal epigastric tenderness. He was noted to have neck stiffness but was Kernig's negative and demonstrated no photophobia. Ear, nose and throat examination revealed purulent tonsils and generalised neck lymphadenopathy, but no evidence of quinsy.

The patient was previously fit and well, and on no regular medications. He lives with his father and works as a manual labourer. He had not been abroad and there were no animals in the household.

Investigations

Initial venous blood gas in A+E showed a lactate of 4.0 mmol/L. Routine laboratory blood tests showed a white cell count of 20 000 cells/mm3 and a C reactive protein of 250 mg/L. Renal function tests revealed an acute kidney injury (creatinine 150 µmol/L, urea 14.5 mmol/L). Platelets were 16 000 cells/mm3. Liver function and haemoglobin levels were normal. Blood cultures grew F. necrophorum. Urine and stool cultures were negative.

CT scan of the head, neck and thorax showed left-sided thrombus in the internal jugular vein, sigmoid sinus and cavernous sinus along with patchy consolidation in both upper lobes of the lungs. It also revealed septic arthritis of the left atlanto-occipital and C1/C2 facet joints with a small left lateral epidural abscess. The patient went on to have MRI of the head and c-spine. This showed, in addition to the CT scans, a left vertebral artery and internal carotid artery thrombosis, skull base osteomyelitis most extensive in the clivus and an extensive epidural abscess (figures 1 and 2).

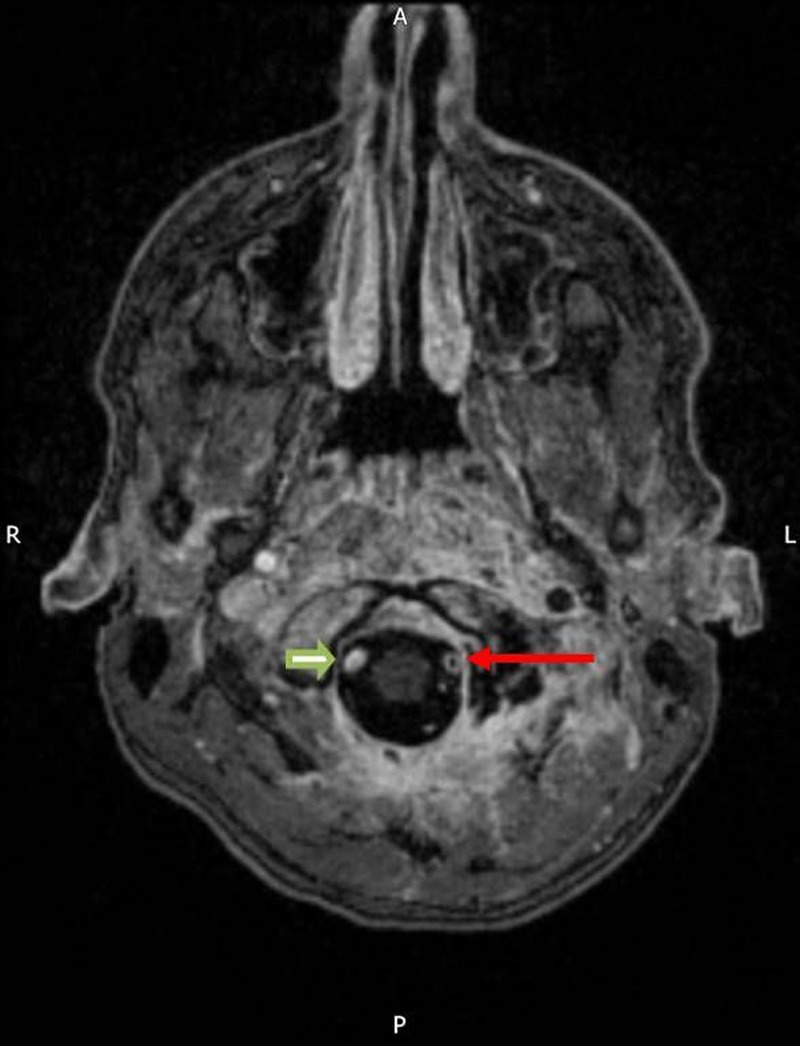

Figure 1.

MRI of the head showing extensive high signal at the skull base consistent with skull base osteomyelitis. Filling defect in left vertebral artery (red arrow) consistent with thrombosis. Note the normal opacification of the right vertebral artery (block green arrow).

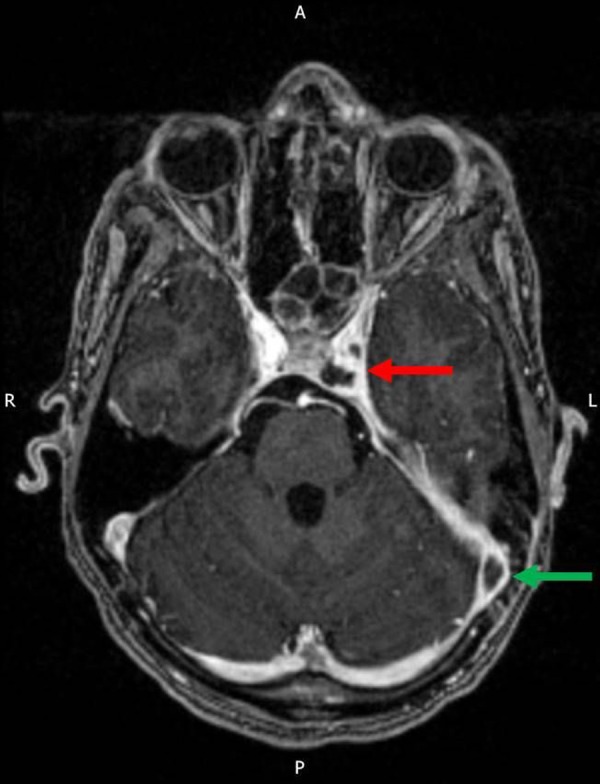

Figure 2.

MRI of the head showing filling defects within the left cavernous sinus (red arrow) and sigmoid sinus (green arrow) consistent with thrombosis.

Treatment

The patient was initially started on ceftriaxone in A+E to cover meningitis and was transferred to intensive treatment unit after remaining hypotensive despite aggressive fluid resuscitation. He subsequently developed a left-sided hypoglossal nerve palsy. His antibiotics were changed to intravenous meropenem and metronidazole on microbiology advice after F. necrophorum was isolated on blood cultures. He was reviewed by the stroke team and started on a 6-month course of warfarin for his cavernous sinus thrombosis. The patient currently remains in hospital on intravenous antibiotics and is receiving further rehabilitation on the stroke ward. He has an on-going hypoglossal nerve palsy.

Discussion

While Lemierre's syndrome classically presents as an oropharyngeal infection, internal jugular vein thrombosis and isolation of anaerobic organisms such as F. necrophorum, it can also encompass a constellation of different complications.2–5 We report a patient with clinical and radiological features of the rare complications of F. necrophorum infection, including clival osteomyelitis and XIIth nerve palsy.

Complications of the central nervous system are, perhaps surprisingly, less common. Abscesses, meningitis and skull base and cranial nerve involvement involving the cervical vertebrae and clivus, have been identified previously in very few case reports. In one case, osteomyelitis of the clivus required surgical drainage of a posterior pharyngeal collection.6 There have also been two documented reports of development of clival syndrome with palsies of the 6th and 12th cranial nerves associated with extensive cervical leptomeningitis followed by epidural abscess formation in children.7 Partial recovery of the cranial nerve function was achieved after conservative treatment with intravenous antibiotic therapy.

Learning points.

Fusobacterium necrophorum, a gram negative anaerobe, is the most common cause of Lemierre's syndrome, an oropharyngeal infection leading to internal jugular vein thrombosis and secondary septic emboli.

As clinicians, it is important for us to recognise the large constellation of possible complications, which can include pulmonary and large joint involvement, significant venous and arterial thrombosis and skull base osteomyelitis.

Clival osteomyelitis, while rare, can cause significant neurological sequela such as VIth and XIIth nerve palsies. This may be managed conservatively with intravenous antibiotics or may need surgical drainage of a collection, as has previously been described.

Significant venous thrombosis may require a period of anticoagulation.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Brazier JS, Hall V, Yusuf E et al. Fusobacterium necrophorum infections in England and Wales 1990–2000. J Med Microbiol 2002;51:269–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baig M, Rasheed J, Subkowitz D et al. A review of Lemierre syndrome. Internet J Infect Dis 2005;5(2). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kempen DH, van Dijk M, Hoepelman AI et al. Extensive thoracolumbosacral vertebral osteomyelitis after Lemierre syndrome. Eur Spine J 2015;24:502–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bentham JR, Pollard AJ, Milford CA et al. Cerebral infarct and meningitis secondary to Lemierre's syndrome. Pediatr Neuro 2004;30:281–3. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2003.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta T, Parikh K, Puri S et al. The forgotten disease: bilateral lemierre's disease with mycotic aneurysm of the vertebral artery. Am J Case Rep 2014;15:230–4. 10.12659/AJCR.890449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fallahian A, Desai N, Jackson MA et al. Ostemyelitis of the clivus due to Fusobacterium necrophorum. Int J Case Rep and Images 2011;2:17–20. 10.5348/ijcri-2011-07-45-CR-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peer Mohamed B, Carr L. Neurological complications in two children with Lemierre syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol 2010;52:779–81. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03718.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]