Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus are Gram-positive bacteria that are the leading cause of recurrent infections in humans that include pneumonia, bacteremia, osteomyelitis, arthritis, endocarditis, and toxic shock syndrome. The emergence of methicillin resistant S. aureus strains (MRSA) has imposed a significant concern in sustained measures of treatment against these infections. Recently, MRSA strains deficient in expression of a serine/threonine kinase (Stk1 or PknB) were described to exhibit increased sensitivity to β-lactam antibiotics. In this study, we screened a library consisting of 280 drug-like, low-molecular-weight compounds with the ability to inhibit protein kinases for those that increased the sensitivity of wild-type MRSA to β-lactams and then evaluated their toxicity in mice. We report the identification of four kinase inhibitors, the sulfonamides ST085384, ST085404, ST085405, and ST085399 that increased sensitivity of WT MRSA to sub-lethal concentrations of β-lactams. Furthermore, these inhibitors lacked alerting structures commonly associated with toxic effects, and toxicity was not observed with ST085384 or ST085405 in vivo in a murine model. These results suggest that kinase inhibitors may be useful in therapeutic strategies against MRSA infections.

Keywords: serine/threonine kinase, sulfonamides, antibiotics, inhibition, mouse

1. Introduction

Bacterial infections remain a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in humans. Staphylococcus aureus are Gram-positive bacteria that cause clinically significant, and sometimes reoccurring, infections [1]. Although S. aureus are frequently found as colonizers in the nose and skin in about 20% of the human population, severe infections due to S. aureus include pneumonia, bacteremia, osteomyelitis, arthritis, endocarditis, and toxic shock syndrome. Furthermore, patients diagnosed with hyper IgE (Jobs) syndrome or chronic granulomatous diseases (CGD) are predisposed to frequent and life-threatening S. aureus infections. While antibiotic therapy is currently used to treat S. aureus infections, the emergence of antibiotic resistant strains, such as those resistant to methicillin and vancomycin, are rapidly exhausting available treatment options [2,3]. MRSA infections are commonly treated with non-β-lactam antibiotics, such as clindamycin and co-trimoxaole [4]. Intravenous administration, toxicity, and limited penetration of glycopeptide antibiotics into deeper tissues impose additional constraints on treatment [5].

MRSA strains lacking serine/threonine kinase (∆stk1) were described to exhibit increased sensitivity to β-lactams [6,7]. Furthermore, the kinase activity of Stk1 was shown to be important for antibiotic resistance as complementation of ∆stk1 with only the kinase domain restored WT level antibiotic resistance [7]. Therefore, we screened a kinase inhibitor library to identify compounds that could increase the sensitivity of MRSA to β-lactam antibiotics. We report the identification of four sulfonamide kinase inhibitors, ST085384, ST085404, ST085405, and ST085399, that increased sensitivity of WT MRSA to sub-lethal concentrations of β-lactams. These findings suggest that kinase inhibitors may be promising in therapeutic strategies against MRSA infections.

2. Results

2.1. Kinase Inhibitors Increase Sensitivity of MRSA to β-Lactam Antibiotics, Such as Nafcillin

We hypothesized that inhibition of Stk1 by kinase inhibitors should increase the sensitivity or minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of MRSA to β-lactam antibiotics. To this end, using methods described [8], we first derived Δstk1 mutants from CA-MRSA strains linked to sequential and overlapping epidemics in the United States (USA300 LAC and USA400 MW2 [9]). Antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed using standards established by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, [10]). Consistent with previous findings [6,7], we observed that ∆stk1 mutants derived from MRSA strains MW2 and LAC showed a dramatic increase in susceptibility to β-lactams (lower MIC, see Table 1). The above results further confirmed that MRSA ∆stk1 mutants are more sensitive to β-lactam antibiotics and provided support for the identification of kinase inhibitors.

Table 1.

Role of Stk1 in β-lactam resistance of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MW2 and LAC).

| MIC (µg/mL) | PEN | AMP | NAF | CXM | CAZ | FEP | IPM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newman (MSSA) | 0.094 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1.5 | 16 | 4 | 0.032 |

| MW2 | 48 | 24 | 32 | >256 | >256 | >256 | 1 |

| MW2∆stk1 | 12 | 12 | 2 | 6 | 32 | 8 | 0.125 |

| LAC | 48 | 32 | 16 | >256 | >256 | >256 | 0.75 |

| LAC∆stk1 | 24 | 24 | 4 | 6 | 12 | 4 | 0.06 |

PEN = Penicillin; AMP = Ampicillin; NAF = Nafcillin; CXM = Cefuroxime; CAZ = Caftazidime; FEP = Cefepime; IMI = Imipenem. Minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined using either Etest strips (AB Biodisk) or growth in liquid broth. For MIC determination in liquid growth, overnight cultures of MRSA strains were inoculated 1:20 in Typtic Soy Broth (TSB) containing different antibiotic concentrations.

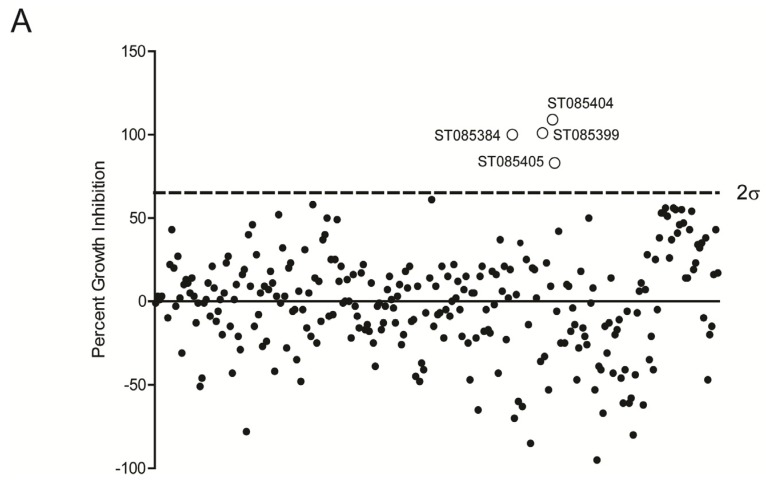

We next screened a library consisting of 280 drug-like, low molecular weight compounds that can inhibit protein kinases (http://www.timtec.net/kinase-modulators-actitarg-k-library.html) for their ability to increase the sensitivity of wild type (WT) MRSA to β-lactams antibiotics. Briefly, WT MRSA (LAC) was grown overnight in the presence of sub-lethal concentrations of NAF (4 µg/mL) in the presence of 40 µg/mL of the respective kinase inhibitor. Controls included MRSA (LAC) grown in the presence of the kinase inhibitor alone, NAF alone, or media alone. As controls, LACΔstk1 was also grown in the presence of the antibiotic, the kinase inhibitor, or media only. The data are shown as % inhibition compared to growth of WT MRSA LAC in the absence of the inhibitor (Figure 1A). These studies revealed that four inhibitors namely ST085384 ([N-(1benzylpiperidin-4-yl)-1-(naphthalen-1ylsulfonyl)piperidine-3carboxamide], ST085399 (N-(4-methylphenyl)-2-oxo-1H-benzo[cd]indole-6-sulfonamide), ST085404 (2-oxo-N-(2-oxonaphtho[2,1-d][1,3]oxathiol-5-yl)-1,2-dihydrobenzo[cd]indole-6-sulfonamide), ST085405 (N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-2-oxo-2H-naphtho[1,8-bc]thiophene-6-sulfonamide), increased sensitivity of WT MRSA to β-lactams (>66% inhibition Figure 1A, see Figure 1B for structures). These kinase inhibitors also did not inhibit growth of the MRSAΔstk1 mutant (i.e., ≤0% growth inhibition).

Figure 1.

Identification of sulfonamides that increase the sensitivity of MRSA to Nafcillin (NAF). (A) Cultures of MRSA WT LAC were grown in the presence of sub-lethal concentration of NAF with various sulfonamides to identify putative kinase inhibitors. Four compounds (ST085384, ST085399, ST085404, and ST085405) caused growth inhibition greater than two standard deviations of the data set; and (B) structures of the four identified sulfonamides.

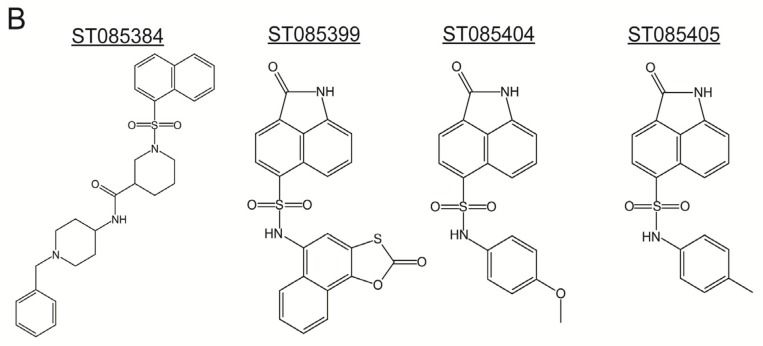

Using ST085384 (Figure 2A) and ST085399 (Figure 2B), we confirmed that growth inhibition of MRSA LAC was observed only in the presence of the β-lactam (Figure 2A,B). At 12.7 µM, ST085384 inhibited growth of MRSA by 52% (Figure 2A), which is comparable to the 58% inhibition observed with staurosporine (a general and potent kinase inhibitor) at a similar concentration (Figure 2C, 13.4 µM). Similar results were observed with MRSA MW2.

Figure 2.

Kinase inhibitors induce a dose-dependent increase in the sensitivity of MRSA to NAF in vitro. Cultures of MRSA WT LAC were grown in the presence or absence of NAF (4 µg/mL) with various concentrations of (A) ST085384; (B) ST085399; or (C) staurosporine. The concentration required for 50% growth inhibition for ST085384 (12.7 µM) was comparable to that of staurosporine (13.4 µM). At the highest concentration used, the kinase inhibitors were at ~25 µg/mL. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; Bonferroni Multiple Comparisons following Two-way ANOVA; n = 2–3).

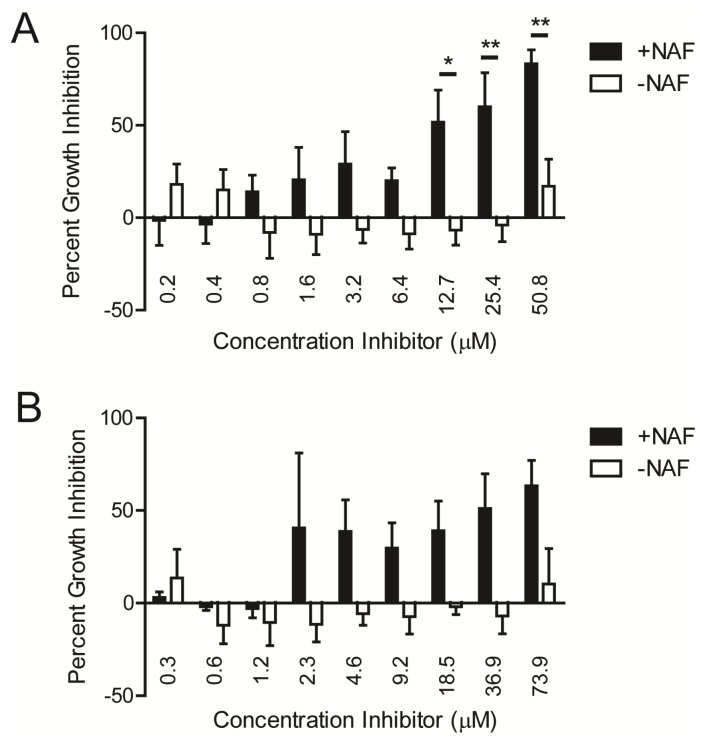

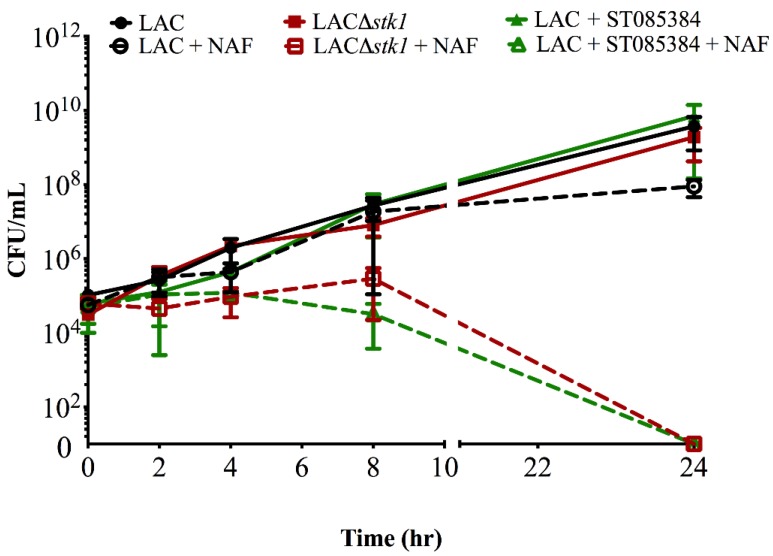

To confirm that the decrease in optical density observed on treatment of MRSA with kinase inhibitor and NAF correlated with decreased bacterial CFU, we performed a time-to-kill analysis, as described [11,12]. Briefly, 104 CFU of WT MRSA (LAC) was grown for 24 h in either media alone, antibiotic NAF alone (4 µg/mL), kinase inhibitor alone (40 µg/mL), or kinase inhibitor containing NAF. For enumeration of viable bacterial CFU, aliquots were serially diluted and plated at 0, 2, 4, 8, and 24 h post-inoculation. As a control, approximately 104 CFU/mL of LACΔstk1 (which is sensitive to NAF) was added to either media alone or media containing NAF (4 µg/mL). The results shown in Figure 3A confirm that treatment of MRSA LAC with the kinase inhibitor and antibiotic NAF was bactericidal, whereas treatment with either only the kinase inhibitor or only the antibiotic NAF did not confer bactericidal activity. Additionally, the bactericidal activity of NAF to MRSA LAC treated with ST085384 is similar to that observed with the β-lactam sensitive MRSA LACΔstk1 treated with NAF.

Figure 3.

The kinase inhibitor ST085384 increases sensitivity of MRSA LAC to the bactericidal activity of Nafcillin (NAF).

The MRSA strain LAC was grown overnight from single colony. The next morning, approximately 104 CFU/mL of LAC was added to 500 µL of either TSB (shown below as LAC), TSB containing NAF (4 µg/mL, shown below as LAC + NAF), TSB containing kinase inhibitor ST085384 (40 µg/mL, shown below as LAC + ST085384), or TSB containing both NAF (4 µg/mL) and ST085384 (40 µg/mL); shown below as LAC + ST085384 + NAF, see green dashed line. As a control, approximately 104 CFU/mL of LACΔstk1 (which is sensitive to NAF) was added to either 500 µL of TSB (see LACΔstk1) or 500 µL of TSB containing NAF (4 µg/mL, see LACΔstk1 + NAF, red dashed line). All cultures were grown in a 37 °C shaker at 220 rpm. Aliquots of the media were removed immediately after subculture (T0) and at 2, 4, 8, and 24 h post-inoculation and were serially diluted and plated on TSA. Plates were incubated for 24–48 h at 37 °C and viable CFU were counted. The experiment was repeated three times. Note that NAF is bactericidal to MRSA LAC only in the presence of the kinase inhibitor ST085384 and is similar to that observed with MRSA LACΔstk1 treated with NAF (see red and green dashed lines).

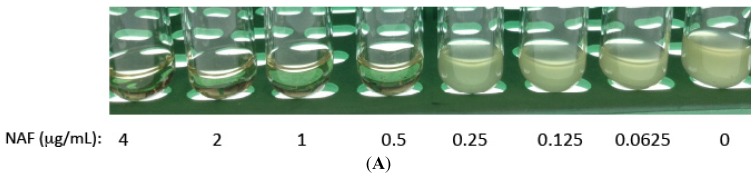

To determine if ST085384 had potential off-target effects that also increased sensitivity of MRSA LACΔstk1 to NAF, we compared growth of LACΔstk1 in the presence of sub-MIC NAF with and without the kinase inhibitor ST085384. To this end, we first determined the MIC and sub-MIC of NAF for LACΔstk1 under the time to kill assay conditions. To this end, approximately 104 CFU/mL of LACΔstk1 was added to 500 μL of TSB containing two-fold serial dilutions of Nafcillin. Under these conditions, we determined that the MIC of NAF for LACΔstk1 to be 0.5 μg/mL, see Figure 4A). The MIC of NAF for LAC∆stk1 under the time to kill assay conditions was lower than that shown in Table 1, likely due to different inoculum densities. Subsequently, ~104 CFU/mL of LACΔstk1 was added to 500 μL of either TSB or TSB containing MIC NAF (0.5 µg/mL), TSB containing sub-MIC NAF (0.25 µg/mL) and TSB containing sub-MIC NAF (0.25 µg/mL + kinase inhibitor ST085384 (40 µg/mL)). Aliquots of the media were removed immediately after subculture (T0) and at 2, 4, 8, and 24 h post-inoculation and were serially diluted and plated in duplicate on TSA. Note that ST085384 did not increase the sensitivity of LACΔstk1 to NAF. Collectively, these data confirm that the kinase inhibitor used in this study increases sensitivity of WT MRSA to ß-lactam antibiotics.

Figure 4.

The kinase inhibitor ST085384 does not increase sensitivity of MRSA LAC∆stk1 to the bactericidal activity of Nafcillin (NAF). (A) The MRSA strain LAC∆stk1 was grown overnight from a single colony. The next morning, approximately 104 CFU/mL of LAC∆stk1 was added to 1 mL TSB without antibiotics or 500 µL of TSB containing two-fold serial dilutions of Nafcillin from 0.0625 µg/mL to 4 µg/mL and was incubated O/N at 37 °C with shaking. The MIC of NAF for LAC∆stk1 under these conditions was determined to be 0.5 µg/mL (see loss of turbidity or lack of growth in Panel A); (B) approximately 104 CFU/mL of LAC∆stk1 was added to 500 µL of either TSB or TSB containing MIC NAF (0.5 µg/mL, indicated as LAC∆stk1 + MIC NAF), TSB containing sub-MIC NAF (0.25 µg/mL, indicated as LAC∆stk1 + sub-MIC NAF), and TSB containing sub-MIC NAF (0.25 µg/mL + kinase inhibitor ST085384 (40 µg/mL), indicated as LAC∆stk1 + sub-MIC NAF + ST085384). All cultures were grown in a 37 °C shaker at 220 rpm. Aliquots of the media were removed immediately after subculture (T0) and at 2, 4, 8, and 24 h post-inoculation, and were serially diluted and plated on TSA. Plates were incubated for 24–48 h at 37 °C and viable CFU were counted. The experiment was repeated twice. Note that ST085384 did not increase sensitivity of LACΔstk1 to NAF.

2.2. Kinase Inhibitors Decrease Stk1 Autophosphorylation

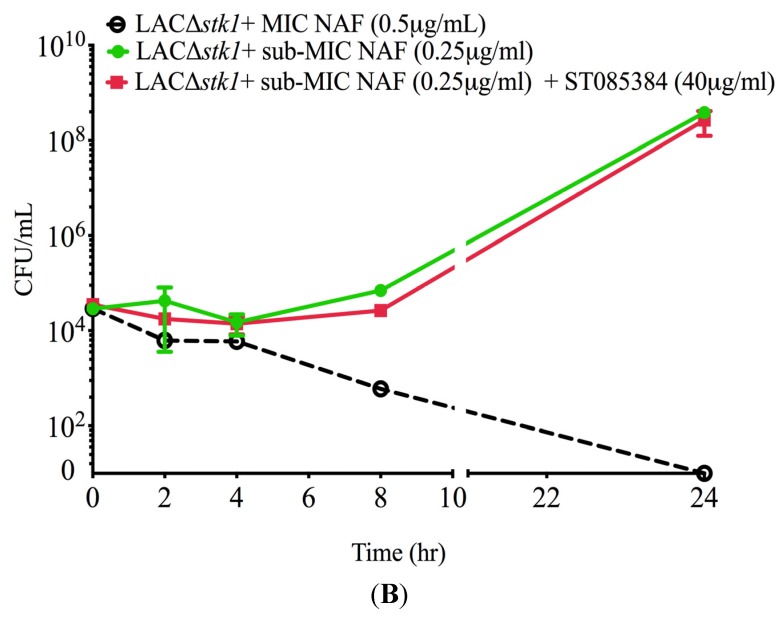

To confirm that kinase inhibitors such as ST085384 can inhibit Stk1 from S. aureus, we performed autophosphorylation assays. To this end, we cloned the coding sequence of the stk1 gene from S. aureus into the expression vector pET32ck [13] to generate a C-terminal His-tagged fusion. Although we used genomic DNA from S. aureus RN4420 as the template for stk1 cloning, we confirmed that the coding sequence of the stk1 gene in S. aureus RN4220 [14] is 100% identical to that found in MRSA USA300 [15]. Stk1 protein was then purified and an aliquot was analyzed on 10% SDS-PAGE followed by Coommasie staining (Figure 5A). Then autophosphorylation asssays were performed in buffer containing 10 µCi [γ 32P]-ATP and either DMSO (control) or Staurosporine (2 µM) or ST085384 (2 µM) for 15 min. Subsequently, all samples were separated by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. Figure 5B shows that autophosphorylation of Stk1 is decreased in the presence of Staurosporine or ST085384 (compare lanes 2 and 3 to 1). These data indicate that the kinase inhibitor ST085384 and Staurosporine can inhibit the activity of S. aureus Stk1.

Figure 5.

Kinase inhibitor ST085384 decreases Stk1 autophosphorylation in vitro. (A) S. aureus Stk1-His6 protein was purified as described in the methods, and an aliquot of the purified protein was resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. Lane 1 represents pre-stained protein standard (BioRad) and Lane 2 presents Stk1-His6 (~1 µg); and (B) autophosphorylation assays of Stk1 was performed using S. aureus Stk1-His6(~1 µg) in kinase buffer containing 10 µCi [γ 32P]-ATP and either DMSO control (lane 1) or Staurosporine (2 µM, lane 2) or ST085384 (2 µM, lane 3). Samples were resolved on 12% SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. Note that autophosphorylation of Stk1 is decreased in the presence of staurosporine (lane 2) and ST085384 (lane 3).

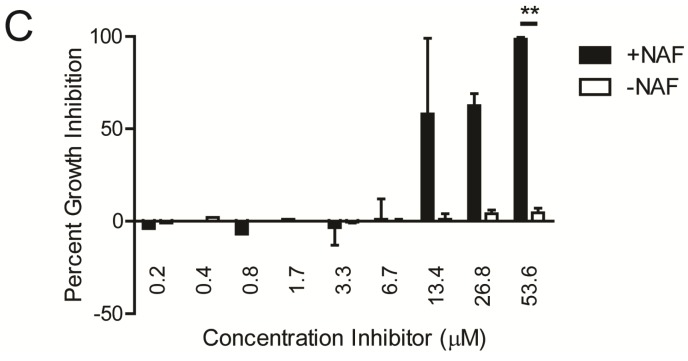

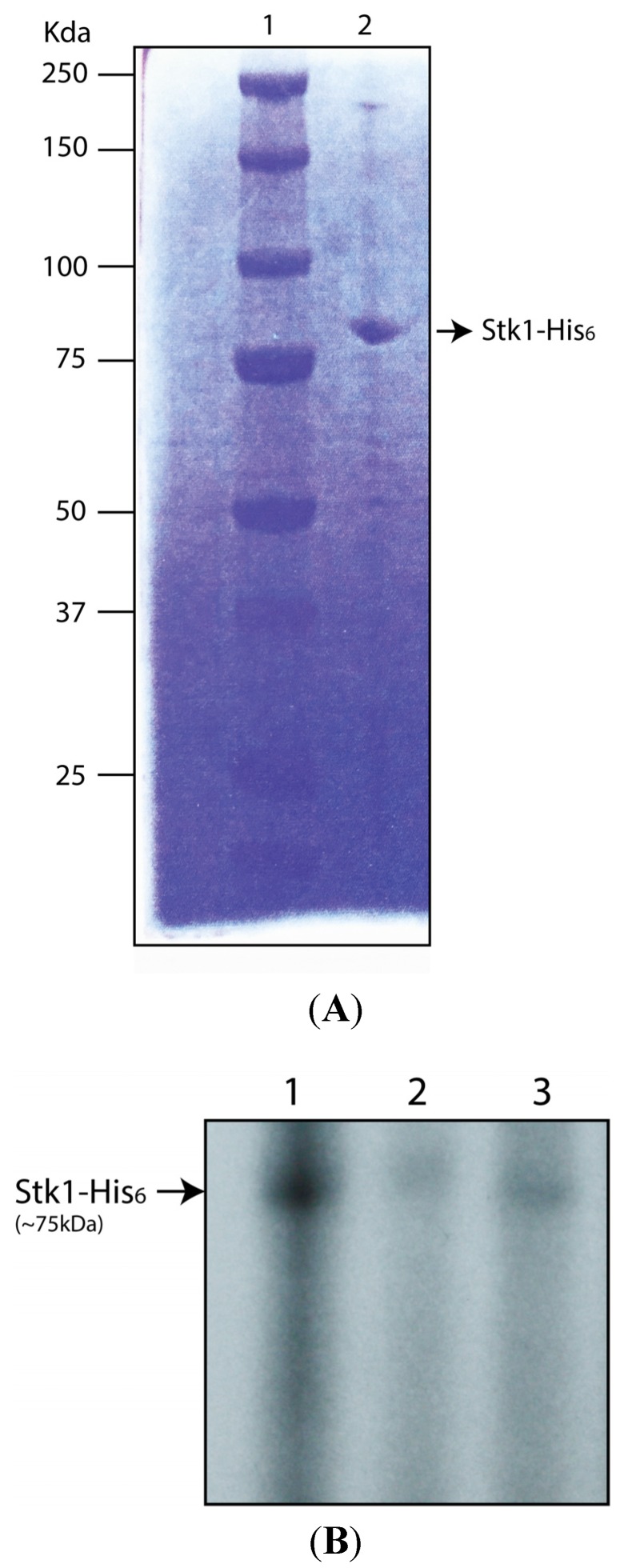

2.3. The Kinase Inhibitor ST085384 Is Tolerated in Mice

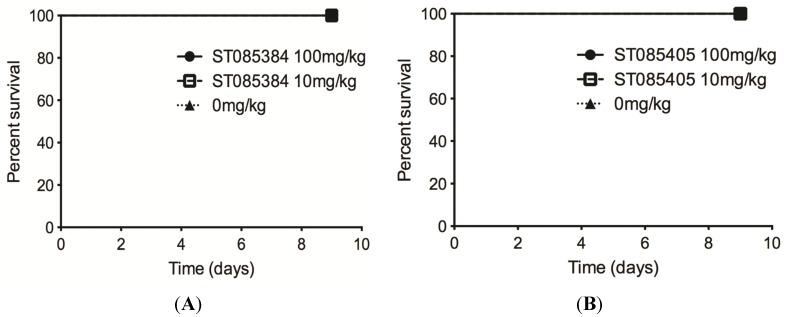

Bioinformatic analysis using the Mobyle FAF-drugs2 software [16] indicated that “alerting structures” commonly associated with toxic effects were not present in ST085384, ST085404, ST085405, or ST085399. Additionally, ST085384, ST085404, ST085405, ST085399 did not exhibit any violations to Lipinski’s rule of five that are important for solubility and permeability of compounds in drug discovery and development [17]. Therefore, we were next interested to determine if the kinase inhibitor/s is tolerated by mice. We chose to test this with the kinase inhibitors ST085384 and ST085405. To this end, we administrated a weight-adjusted dose of ST085384 or ST085405 in Cremaphor EL intraperitoneally to six-week old female C57BL/6J mice (n = 14/group, weight range 15–20 g). Inhibitor doses included 0 (Cremaphor EL, vehicle control), 10 and 100 mg/kg. All groups of mice were continuously monitored for signs of morbidity for a period of nine days. Collectively, these results shown in Figure 6 indicates that at a 100 mg/kg dose, ST085384 and ST085405 are non-toxic to mice, and are better tolerated than the general and potent kinase inhibitor, staurosporine (LD50 = 6.5 mg/kg [18]). These studies provide the foundation for future work to determine if kinase inhibitors that enhance MRSA susceptibility to β-lactams in vivo.

Figure 6.

The kinase inhibitors ST085384 and ST085405 are tolerated in mice. Survival of mice injected with 100 mg/kg (black circle and solid line), 10 mg/kg (hollow square and dashed line), or vehicle only (0 mg/kg; black triangle and dotted line) of (A) ST085384 or (B) ST085405 was monitored for nine days post-injection. Note that all mice survived.

3. Discussion

S. aureus is one of five of the most common causes of nosocomial infections with an estimated 500,000 patients contracting a S. aureus infection each year [19]. As only 2% of all S. aureus isolates are sensitive to penicillin, this imposes significant constraints on treatment of these infections. A better understanding of mechanisms that increase antibiotic resistance in S. aureus is critical for development of new strategies.

In this study, we screened a kinase inhibitor library comprising low molecular weight sulfonamides and identified four inhibitors (ST085384, ST085404, ST085405, ST08539969) that increased the sensitivity of MRSA to β-lactams in vitro. Additional compounds that were structurally similar to the inhibitors exhibited reduced or minimal activity in our screen. This may be due to differences in cell permeability, or due to poor affinity of these compounds for MRSA Stk1. Future work, including purification and crystallization of Stk1 in complex with the effective inhibitors, is necessary to understand the exact mode of interaction.

Recently, Pensinger et al. [20] indicated that the general kinase inhibitor staurosporine did not increase sensitivity of MRSA to ceftrioxone leading to the notion that pharmacological inhibition of Stk1 may not be useful for MRSA. In contrast, we observed that staurosporine and the kinase inhibitors (ST085384, ST085404, ST085405, ST08539969) increased the sensitivity of MRSA to β-lactams such as Nafcillin. Additionally, in contrast to Pensinger et al. [20], we observed that staurosporine decreases autophosphorylation of S. aureus Stk1 in vitro (Figure 4). We speculate that the differing results on the role of staurosporine in Stk1 autophosphorylation may, in part, be due to one or all of the following: we used a full length his-tagged Stk1 whereas Pensinger et al. [20] used a GST tagged Stk1 kinase domain protein; other small differences were in reaction conditions and the composition of kinase buffer (see experimental methods and Pensinger et al. [20] for details). Nevertheless, our findings and previous studies by Tamber et al. [7] corroborate the notion that the kinase domain of the eukaryotic-like serine/threonine kinase regulates antibiotic resistance in MRSA. Consistent with these observations, inhibition of a kinase homologue also led to increased β-lactam susceptibility in Listeria monocytogenes [20], suggesting that there may be a common underlying mechanism. In contrast, varying results were obtained on the effect of kinase inhibitors that inhibit the essential serine/threonine PASTA kinases and growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis [21,22]. However, a recent study indicated that the extracellular PASTA domain of serine/threonine kinases is essential for peptidoglycan remodeling and growth of M. tuberculosis [23]. This requirement of the PASTA domain of serine/threonine kinases in M. tuberculosis, rather than the kinase domain (as seen in MRSA) may, in part, contribute to the discrepancy in the effect of kinase inhibitors in various microorganisms.

We also observed that administration of two of the identified inhibitors (ST085384, ST085405) at 100 mg/kg dose did not induce any obvious morbidity or mortality in mice. However, further studies demonstrating the efficacy of the kinase inhibitors in vivo and establishing the lack of adverse symptoms at these concentrations are necessary to develop efficacious and safe inhibitors. In summary, the identification of kinase inhibitors that increase sensitivity of MRSA to β-lactams in vitro provides an avenue for exploration of alternative therapeutic strategies that can potentially decrease the severity of MRSA infections.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Strains and Chemicals

Wild-type (WT) MRSA strains used in this study are clinical isolates MW2 (USA400) and LAC (USA300) [9]. Stk1 mutants in LAC and MW2 were constructed as described [8].

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. The kinase inhibitor library and the kinase inhibitors ST085384 and ST085405 were purchased from TimTec (Newark, NJ, USA, http://www.timtec.net/).

4.2. STK Inhibitor Library Screen

The kinase inhibitor library consisting of 1 mg each of 280 drug-like, low molecular weight sulfonamide compounds that can inhibit protein kinases were obtained from TimTec in a 96-well format (http://www.timtec.net/kinase-modulators-actitarg-k-library.html). Kinase inhibitors were re-suspended in DMSO (1 mg/mL). Overnight cultures of MRSA were subcultured 1:20 in tryptic soy broth (TSB), Nafcillin (NAF) was added to a final concentration of 4 μg/mL and dispensed into 96-well plates (100 µL/well). The kinase inhibitor was added to a final concentration of 40µg/mL, and the plate was incubated at 37 °C overnight with shaking. Bacterial growth was measured by recording the change in optical density at 600 nm (∆OD600nm) from before (T0) and after overnight incubation (TO/N). Percent inhibition was calculated using the formula ∆OD600nm of “no inhibitor” control (max growth) −∆OD600nm of sample (inhibitor + NAF)/∆OD600nm of “no inhibitor” (max growth) × 100. As a control, each plate contained un-inoculated wells where no growth was observed. Additional controls also included wells that contained TSB + NAF (4 μg/mL) inoculated with the MRSAΔstk1 strain. Compounds with activity above two standard deviations of the sample set were further investigated. To calculate the MIC of these putative inhibitors in the presence and absence of Nafcillin, S. aureus cultures were prepared as described above and exposed to varying concentrations of each putative inhibitor.

4.3. Time-to-Kill Assay

The MRSA strain LAC was grown overnight from single colony. The next morning, approximately 104 CFU/mL of LAC was added to 500 µL of either TSB, TSB containing NAF (4 µg/mL), TSB containing kinase inhibitor ST085384 (40 µg/mL), or TSB containing both NAF (4 µg/mL) and ST085384 (40 µg/mL). As a control, approximately 104 CFU/mL of LACΔstk1 (which is sensitive to NAF) was added to either 500 µL of TSB or 500 µL of TSB containing NAF (4 µg/mL). All cultures were grown in a 37 °C shaker at 220 rpm. Aliquots of the media were removed immediately after subculture (T0) and at 2, 4, 8, and 24 h post-inoculation and were serially diluted and plated on TSA. Plates were incubated for 24–48 h at 37 °C and viable CFU were counted. The experiment was repeated three times. The above experiment was repeated with LAC∆stk1-see Figure legend for details.

4.4. Protein Purification and in Vitro Phosphorylation Assays

The S. aureus stk1 gene was cloned into the expression vector pET32ck [13] to generate a C-terminal His-tagged fusion. To this end, Stk1 was PCR amplified using High Fidelity PCR (Primestar, Clonetech, Mountain View, CA, USA), the primer pairs 6His-SaSTKBamH1F and 6His-SaSTKXhoIR, and S. aureus RN4220 genomic DNA as the template. Of note, we confirmed that the coding sequence of the stk1 gene in S. aureus RN4220 [14] is 100% identical to that found in MRSA USA300 [15]. The PCR product was digested with the enzymes for which restriction sites were engineered in the primers and were cloned in frame into the multiple cloning site (MCS) of pET32CK to obtain C-terminal His6 fusion protein. The recombinant plasmid was sequenced and expression was induced in E. coli BL21DE3 with 1mM IPTG at 16 °C overnight, shaking until cultures reached OD600 = 0.8. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, and His-tagged fusion protein was purified from cell free extracts using nickel affinity chromatography as described by the manufacturer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA; (https://www.qiagen.com/us/resources/resourcedetail?id=0de4b003-4521-4fdc-923d-d304bdaddf5b&lang=en)). An aliquot of the purified Stk1 protein was analyzed using 10% SDS-PAGE followed by staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). The purified protein was quantified using Bradford’s Reagent (Sigma). Subsequently Stk1 autophosphorylation was performed as described [24]. Briefly, ~1 µg of purified Stk1 protein was incubated in kinase buffer (50 mM TrisHCl pH 7.5, 1 mM MnCl2, 1 µM ATP) containing 10 µCi [γ 32P] ATP (PerkinElmer) and either DMSO (control) or Staurosporine (2 µM) or ST085384 (2 µM) for 15 min. Subsequently, all reactions were heated to 100 °C for 5 min. The samples were then analyzed on 12% SDS-PAGE and exposed to autoradiography.

Primer Sequence

6His-SaSTKBamH1F: 5′ TAGAGGATCCATGATAGGTAAAATAATAAATGAAC 3′

6His-SaSTKXhoIR: 5′ TGAACTCGAGTACATCATCATAGCTGACTTCTT 3′

4.5. Animal Studies

Ethical Approval: All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol 13311) and performed using guidelines in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th Edition) and ARRIVE. To test if ST085384 and ST085405 are tolerated in vivo, mice were given an intraperitoneal dose of inhibitor (dissolved in Cremophor:Ethanol:PBS at 1:1:4) at 0, 10, or 100 mg/kg. Mice were monitored for survival for nine days.

Acknowledgments

We thank Charles Skip Smith for helpful discussions.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed towards the design and performance of experiments, analysis of the results and manuscript preparation.

Conflicts of Interest

This work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health, Grants NIH R01AI070749, NIH R56 AI070749, NIH R21 AI109222 and from Seattle Children’s Research Institute to Lakshmi Rajagopal.

Christopher Whidbey was supported by the NIH training grant (T32 AI07509, PI: Lee Ann Campbell) and UW GO-MAP Fellowship. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The work presented in this manuscript is patented under the US Patent: “Kinase inhibitors capable of increasing the sensitivity of bacterial pathogens to β-lactam antibiotics” Lakshmi Rajagopal, Kellie Burnside Howard, Christopher Whidbey. PCT Application Number: PCT/US2012/050635. Filing Date: 13 August 2012 (Submission Date: 15 August 2011).

Please note that the work presented in the manuscript has been updated since the patent filing. We have no other competing interests.

References

- 1.Styers D., Sheehan D.J., Hogan P., Sahm D.F. Laboratory-based surveillance of current antimicrobial resistance patterns and trends among Staphylococcus aureus: 2005 status in the United States. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2006 doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-5-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seybold U., Kourbatova E.V., Johnson J.G., Halvosa S.J., Wang Y.F., King M.D., Ray S.M., Blumberg H.M. Emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 genotype as a major cause of health care-associated blood stream infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006;42:647–656. doi: 10.1086/499815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noskin G.A., Rubin R.J., Schentag J.J., Kluytmans J., Hedblom E.C., Jacobson C., Smulders M., Gemmen E., Bharmal M. National trends in Staphylococcus aureus infection rates: Impact on economic burden and mortality over a 6-year period (1998–2003) Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007;45:1132–1140. doi: 10.1086/522186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu C., Bayer A., Cosgrove S.E., Daum R.S., Fridkin S.K., Gorwitz R.J., Kaplan S.L., Karchmer A.W., Levine D.P., Murray B.E., et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the infectious diseases society of america for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: Executive summary. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011;52:285–292. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butler M.S., Hansford K.A., Blaskovich M.A., Halai R., Cooper M.A. Glycopeptide antibiotics: Back to the future. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo). 2014;67:631–644. doi: 10.1038/ja.2014.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beltramini A.M., Mukhopadhyay C.D., Pancholi V. Modulation of cell wall structure and antimicrobial susceptibility by a Staphylococcus aureus eukaryote-like serine/threonine kinase and phosphatase. Infect. Immun. 2009;77:1406–1416. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01499-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tamber S., Schwartzman J., Cheung A.L. Role of PknB kinase in antibiotic resistance and virulence in community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain USA300. Infect. Immun. 2010;78:3637–3646. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00296-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burnside K., Lembo A., de Los Reyes M., Iliuk A., Binhtran N.T., Connelly J.E., Lin W.J., Schmidt B.Z., Richardson A.R., Fang F.C., et al. Regulation of hemolysin expression and virulence of Staphylococcus aureus by a serine/threonine kinase and phosphatase. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeLeo F.R., Chambers H.F. Reemergence of antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the genomics era. J. Clin. Investig. 2009;119:2464–2474. doi: 10.1172/JCI38226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wikler M.A. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; Wayne, PA, USA: 2008. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 18th informational supplement M100-Sl8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pankey G., Ashcraft D., Kahn H., Ismail A. Time-kill assay and Etest evaluation for synergy with polymyxin B and fluconazole against Candida glabrata. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58:5795–5800. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03035-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vasicek E.M., Berkow E.L., Bruno V.M., Mitchell A.P., Wiederhold N.P., Barker K.S., Rogers P.D. Disruption of the transcriptional regulator Cas5 results in enhanced killing of Candida albicans by Fluconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58:6807–6818. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00064-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seepersaud R., Needham R.H., Kim C.S., Jones A.L. Abundance of the delta subunit of RNA polymerase is linked to the virulence of Streptococcus agalactiae. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:2096–2105. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.6.2096-2105.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nair D., Memmi G., Hernandez D., Bard J., Beaume M., Gill S., Francois P., Cheung A.L. Whole-genome sequencing of Staphylococcus aureus strain RN4220, a key laboratory strain used in virulence research, identifies mutations that affect not only virulence factors but also the fitness of the strain. J. Bacteriol. 2011;193:2332–2335. doi: 10.1128/JB.00027-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diep B.A., Gill S.R., Chang R.F., Phan T.H., Chen J.H., Davidson M.G., Lin F., Lin J., Carleton H.A., Carleton E.F., et al. Complete genome sequence of USA300, an epidemic clone of community-acquired meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet. 2006;367:731–739. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lagorce D., Sperandio O., Galons H., Miteva M.A., Villoutreix B.O. FAF-Drugs2: Free ADME/tox filtering tool to assist drug discovery and chemical biology projects. BMC Bioinform. :2008. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lipinski C.A., Lombardo F., Dominy B.W., Feeney P.J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001;46:3–26. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Omura S., Iwai Y., Hirano A., Nakagawa A., Awaya J., Tsuchya H., Takahashi Y., Masuma R. A new alkaloid AM-2282 OF Streptomyces origin. Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation and preliminary characterization. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 1977;30:275–282. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.30.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson N.B., Hayes L.D., Brown K., Hoo E.C., Ethier K.A. CDC National Health Report: Leading Causes of Morbidity and Mortality and Associated Behavioral Risk and Protective Factors—United States, 2005–2013. [(accessed on 20 October 2015)]; Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/su6304a2.htm. [PubMed]

- 20.Pensinger D.A., Aliota M.T., Schaenzer A.J., Boldon K.M., Ansari I.U., Vincent W.J., Knight B., Reniere M.L., Striker R., Sauer J.-D. Selective pharmacologic inhibition of a PASTA kinase increases Listeria monocytogenes susceptibility to beta-lactam antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58:4486–4494. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02396-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magnet S., Hartkoorn R.C., Szekely R., Pato J., Triccas J.A., Schneider P., Szántai-Kis C., Orfi L., Chambon M., Banfi D., et al. Leads for antitubercular compounds from kinase inhibitor library screens. Tuberculosis (Edinburgh) 2010;90:354–360. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lougheed K.E., Osborne S.A., Saxty B., Whalley D., Chapman T., Bouloc N., Chugh J., Nott T.J., Patel D., Spivey V.L., et al. Effective inhibitors of the essential kinase PknB and their potential as anti-mycobacterial agents. Tuberculosis (Edinburgh) 2011;91:277–286. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turapov O., Loraine J., Jenkins C.H., Barthe P., McFeely D., Forti F., Daniela G., Dusan H., Mijoon L., Andrew R., et al. The external PASTA domain of the essential serine/threonine protein kinase PknB regulates mycobacterial growth. Open Biol. 2015 doi: 10.1098/rsob.150025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rajagopal L., Vo A., Silvestroni A., Rubens C.E. Regulation of cytotoxin expression by converging eukaryotic-type and two-component signalling mechanisms in Streptococcus agalactiae. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;62:941–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05431.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]