Abstract

Background:

Root canal sealers help to minimize leakage, provides antimicrobial activity to reduce the possibility of residual bacteria, and to resolve periapical lesion.

Aim:

To compare five different root canal sealers against Enterococcus faecalis in an infected root canal model by using real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).

Settings and Design:

Sixty human mandibular premolars were sectioned to standardize a uniform length of 14 mm. Fifty microliters of the inoculum containing E. faecalis were transferred into each microcentrifuge tube (n = 60). The samples were divided into six groups Tubli-Seal, Apexit Plus, Fillapex, AH Plus, RoekoSeal, and Positive control, respectively.

Materials and Methods:

Five groups after the incubation with the microorganism E. faecalis were coated with different root canal sealers and obturated using F3 ProTaper Gutta-percha point. The dentinal shavings were collected and analyzed for RT-PCR.

Statistical Analysis:

The mean difference between six groups was calculated using analysis of variance and post-hoc test.

Results:

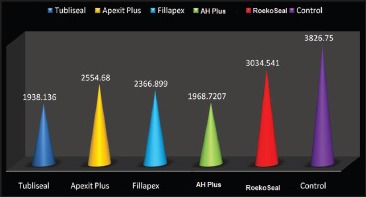

The highest antibacterial activity was achieved with Tubli-Seal (1938.13 DNA in pictogram [pg]) and least by RoekoSeal (3034.54 DNA in pg).

Conclusion:

The maximum antimicrobial activity was achieved AH Plus and Tubli-Seal. RT-PCR can be used as a valuable and accurate tool for testing antimicrobial activity.

Keywords: Dentine blocks, Enterococcus faecalis, polymerase chain reaction, root canal sealer

INTRODUCTION

The endodontic microflora is typically a polymicrobial flora consisting of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, but it is dominated by obligate anaerobes. The main objective of root canal treatment is to eliminate bacteria from the infected root canal and also to prevent reinfection of the root canal.[1,2] Enterococcus faecalis is a Gram-positive, facultative anaerobe and is a microorganism which can survive at extreme challenges. It also possess a number of virulence factors that allow adherence to host cells and extracellular matrix, facilitate tissue invasion, effect immunomodulation, and cause toxin-mediated damage.[3]

The use of sealers with antibacterial properties may be advantageous, especially in clinical situations of persistent or recurrent infection. It is important for us to use a sealer that has effective antimicrobial properties against these microorganisms in order to achieve a successful root canal therapy. This along with proper cleaning and shaping will help us in achieving the main goal of complete elimination of bacteria and the colonization of residual microorganisms.[4]

Numerous studies have been evaluated to assess the antimicrobial efficacy of different root canal sealers. It is seen that the agar diffusion test is the most commonly used technique, but it has many drawbacks as it is dependent on the diffusion and the physical properties of the materials being tested.[5] The recently introduced molecular diagnostic methods are based on the investigation of bacterial DNA and RNA. Over the last few years, microbiological techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) have improved the sensitivity of microbial detection compared to culturing and have therefore enabled the identification of enterococci with greater precision.[6] These tests have both high sensitivity and specificity and can help to identify both cultivable and the as yet uncultivated bacterial species.[7]

The aim of this study was to compare five different root canal sealers against E. faecalis in an infected root canal model by using real-time PCR (RT-PCR).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sixty single-rooted human mandibular first premolars were sectioned at or below the cementoenamel junction with a diamond disc and adjusted to 14 mm length. The working length was established approximately 1 mm short of the root length which was confirmed radiographically. All the root canals were instrumented with the Universal ProTaper rotary system (Dentsply Maillefer, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer's instructions at a rotational speed of 300rpm using an endomotor (Endo Mate NSK, Japan). After root canal instrumentation, the teeth were irrigated with a sequence of 17% EDTA for 1 min to remove the smear layer and then rinsed with 5% NaOCl for 1 min. The teeth were then sterilized by autoclaving for 15 min at 121°C (15 lb pressure) and stored in a sterile pouch until use.

Preparation of inoculums

A suspension of 50 μl of E. faecalis (ATCC 29212) strain was incubated in 5 ml of Trypticase Soy agar broth culture medium (Difco, Sparks, MD, USA) at 37°C in an incubator for 4 h. The concentration of the inoculation was then adjusted to a level of turbidity 1 according to the McFarland scale (BioMerieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France), which corresponds to a bacterial load of 3 × 108 cells/ml which is referent to an optical density of 550 nm. Fifty microliters of the inoculums containing E. faecalis were transferred into each microcentrifuge tube (n = 60). Contamination of the dentine specimens was carried out for 21 days at 37°C. Two samples were then randomly selected for bacterial penetration into the dentinal tubules which was confirmed using scanning electron microscope. The samples (60) were divided into six groups:

Group 1: Tubli-Seal,

Group 2: Apexit plus,

Group 3: Fillapex,

Group 4: AH Plus,

Group 5: RoekoSeal, and

Group 6: Positive control.

Obturation of samples

The different sealers were mixed according to the manufacturer's instructions, and the sealers were applied to the root canals of the respective groups by using a lentulo spiral — (ISO size 25). Five groups after the incubation with the microorganism E. faecalis were obturated using (F3) ProTaper Gutta-percha point (Dentsply Tulsa dental, USA) corresponding to ISO size 30. In each study group, lateral condensation technique was performed. In group 6, samples were incubated with E. faecalis, dried with paper points, and not obturated (positive control).

Preparation of dentin blocks

All the samples (n = 60) were then placed onto sterile microplates and stored at 37°C and 100% humidity for about 1 week in order to allow the sealers to set. Then, approximately 3 mm from the apical portion of the samples was resected horizontally, and dentine blocks were obtained (11 mm). The remaining 11 mm was used for the evaluation of antimicrobial activity.

Removal of root filling

The root canal filling was removed using sterile peeso reamers size 2 (ISO size 90) and 3 (ISO size 110), and the root canals were then enlarged using size 4 (ISO size 130) to obtain the dentinal shavings from each sample.[1] The dentinal shavings were then collected in microcentrifuge tubes.

Bacterial genomic DNA isolation from teeth

One milliliter of lysozyme stock solution was added to the dentinal shavings that were collected from all the groups and vortexed, and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. This is followed by the addition of an equal volume of phenol-chloroform and mixed by vortexing at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The final supernatant was collected and dried. Thirty microliters of sterile water were added to dissolve the DNA which was ready for the RT-PCR analysis. RT-PCR was performed by monitoring the increase in fluorescence intensity of the SYBR Green dye with a Rotor-Gene 3000 RT-PCR apparatus (Corbett Research) according to the manufacturer's instructions. All measurements were performed in triplicate. RT-PCR data were represented as cycle threshold (Ct) values, where Ct was defined as the Ct of PCR when amplified product was first detected. The Ct or threshold value of the target sequence is directly proportional to the absolute concentration when compared with the threshold value for reference genes.

Statistical analysis

The data was analyzed using One way ANOVA followed by post hoc test (Bonferroni test) in order to evaluate the significant difference between the six groups. Post-hoc test, that is, Bonferroni test was performed. P < 0.005 was considered significant Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

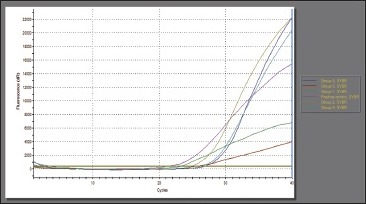

PCR determines the results in Ct [Graphs 1 and 2]. Ct is inversely proportional to the amount of target DNA and hence, the number of microorganisms in the sample. When the control groups were subjected to RT-PCR for detection of DNA load, the mean values were in the range of 3826.75 DNA in pictogram (pg) for E. faecalis. DNA load for all the different groups of root canal sealers were compared with the values attained in the control group and was found to be statistically significant (P < 0.005). Statistically significant reduction was seen in Group 4 (AH Plus) followed by Group 1 (Tubli-Seal), Group 3 (Fillapex), Group 2 (Apexit Plus), and least reduction was seen in Group 5 (RoekoSeal).

Graph 1.

Amplification plot (real-time polymerase chain reaction) for Enterococcus faecalis

Graph 2.

Comparison of DNA load of Enterococcus faecalis in different groups of root canal sealers

DISCUSSION

The ex vivo root canal model which was used with some modification in this study was developed by Haapasalo and Orstavik. This sample model was selected because it induces a clinical situation in the root canal model and also enables the assessment of antibacterial activity inside the dentinal tubules.[8]

In the present study, E. faecalis was chosen as the test microorganism because they have been recovered in 30-70% of root-filled teeth with persistent periapical lesions. The species E. faecalis has some intrinsic characteristics that allow it to survive in conditions that are commonly lethal for many other microorganisms. It also has the property to endure a high alkaline pH of 11.5. The mechanism of alkaline tolerance is by a functioning cell-wall-associated proton pump, which drives protons into the cell in order to acidify the cytoplasm and this plays an important role in the survival of the organism in the highly alkaline environment.[2,3,9]

To overcome the limitations associated with culture techniques, molecular biology methods have been introduced. These methods are based upon the investigation of bacterial DNA and RNA.[7] The advantages associated with RT-PCR are the detection of not only cultivable species, but also of uncultivable microbial species or strains. It has higher specificity and accurate identification of microbial strains with ambiguous phenotypic behavior, including divergent or convergent strains. It detects microbial species directly in the clinical samples without the need for cultivation. It has higher sensitivity and is less time-consuming. RT-PCR offers rapid diagnosis, which is particularly advantageous in cases of life-threatening diseases or diseases caused due to slow growing microorganisms.[10] There are several other possible explanations also for the higher prevalence values of E. faecalis as detected in PCR when compared to culture. One possible reason for differences is the ability of molecular methods to detect DNA from dead cells as well.[11]

RT-PCR analysis showed a load of 1938.13 DNA in pg for Tubli-Seal when compared with the control group (3826.75 DNA in pg) against E. faecalis and it was found to have the highest antibacterial activity when compared with the other sealers used in this study and it was also found to be statistically significant (P < 0.05). The antimicrobial activity of Tubli-Seal is primarily due to the presence of eugenol. Eugenol, which is a phenolic compound, is bactericidal at relatively high concentrations, and it is able to induce cell destruction and inhibit cell growth, respiration, and inhibit E. faecalis intrinsic mechanism.[12,13,14]

The antimicrobial activity of AH Plus is due to the presence of bisphenol- A-diglycidylether. Extracts of paste A (containing epoxy resin) and paste B (containing amines) are mixed together, whereby the sealer reduced the cell viability. This suggests that amines and epoxy resin can also be toxic and that unpolymerized residues in the mixture might maintain the toxic effect.[15,16,17] Also, this sealer has a good flow, thereby diffusing into the dentinal tubules and creating microbial inhibition by means of entombment.[18] The MTA-based sealer Fillapex is more stable, providing a constant release of calcium ions, and maintains a pH, which provides the antibacterial effects and it also has a strong affinity for the release of hydroxyl ions.[19] The initial high pH (10.3) of Fillapex is a significant advantage, as it is able to exert its effect on the bacterial cell membrane and the protein structure.[20,21]

Apexit Plus is a calcium hydroxide-based sealer which enables and promotes the induction of mineralization, apical closure by cementogenesis, inhibits root resorption, and also prevents microleakage.[22,23] The antimicrobial effect exerted by Apexit Plus is due to the ionic dissociation of the sealer into calcium (Ca2+) and hydroxyl (OH-) ions, leading to an increase in pH (12.5). A pH >9 reversibly or irreversibly inactivates the microbial cell membrane enzymes, resulting in the loss of biological activity and destruction of the cytoplasmic membrane.[24,25]

RoekoSeal is a silicone-based root canal sealer that ensures a homogeneous mix, free of air bubbles, and the rheology can be carefully controlled by the addition of the appropriate amount of filler.[26,27] The small filler particle size ensures that this material has excellent flow properties and can achieve a lesser film thickness, which allows the sealer to flow into tiny crevices and tubules.[28]

However, there are a few limitations associated with RT-PCR such as the detection of dead cells by a given identification method can be regarded as a double-edged sword. This can be both an advantage and also a limitation of the method.[10] This ability can allow detection of uncultivable bacteria or fast-growing bacteria that can die during sampling, transportation, or isolation procedures.[7,10] Also, if the bacteria were already dead in the infected site, they may also be detected and this might give rise to a false assumption about their role in the infectious process. To minimize this potential problem, some adjustments in the method for DNA detection or take advantage of the technology derivatives that detect RNA. As for modifications in DNA-based techniques, designing primers to generate large PCR amplicons reduces the risks of positive results due to DNA from dead cells, because DNA remnants, if present, are usually fragmented.[7,10]

Within the root canal system, the antimicrobial activity of root canal sealer is beneficial as it might destroy the remaining microbes that are not destructed by cleaning, shaping, and intracanal medicaments. The selection of sealer is very important for the healing of periradicular tissues as well as for the antimicrobial activity inside the root canal.

CONCLUSION

Within the limitations of this in vitro study, it can be concluded that the maximum antimicrobial activity against E. faecalis was achieved with AH Plus and Tubli-Seal and the least with RoekoSeal. RT-PCR can be used as a valuable and accurate tool for testing antimicrobial activity of root canal sealers.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Saleh IM, Ruyter IE, Haapasalo M, Ørstavik D. Survival of Enterococcus faecalis in infected dentinal tubules after root canal filling with different root canal sealers in vitro . Int Endod J. 2004;37:193–8. doi: 10.1111/j.0143-2885.2004.00785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinheiro ET, Gomes BP, Ferraz CC, Sousa EL, Teixeira FB, Souza-Filho FJ. Microorganisms from canals of root-filled teeth with periapical lesions. Int Endod J. 2003;36:1–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2003.00603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kayaoglu G, Ørstavik D. Virulence factors of Enterococcus faecalis: Relationship to endodontic disease. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2004;15:308–20. doi: 10.1177/154411130401500506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arvind A, Gopikrishna V, Kandaswamy D, Jeyavel RK. Comparative evaluation of the antimicrobial efficacy of five endodontic root canal sealers against Enterococcus faecalis and Candida albicans. J Conserv Dent. 2006;9:2–12. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Özcan E, Eldeniz AU, Ari H. Bacterial killing by several root filling materials and methods in an ex vivo infected root canal model. Int Endod J. 2011;44:1102–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2011.01928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Preethee T, Kandaswamy D, Hannah R. Molecular identification of an Enterococcus faecalis endocarditis antigen efaA in root canals of therapy-resistant endodontic infections. J Conserv Dent. 2012;15:319–22. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.101886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Figdor D, Gulabivala K. Survival against the odds: Microbiology of root canals associated with post-treatment disease. Endod Topics. 2011;18:62–77. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haapasalo M, Orstavik D. In vitro infection and disinfection of dentinal tubules. J Dent Res. 1987;66:1375–9. doi: 10.1177/00220345870660081801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Portenier I, Waltimo TM, Haapasalo M. Enterococcus faecalis — The root canal survivor and ‘star’ in post treatment disease. Endod Topics. 2003;6:135–59. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siqueira JF, Jr, Rôças IN. Exploiting molecular methods to explore endodontic infections: Part 1 — current molecular technologies for microbiological diagnosis. J Endod. 2005;31:411–23. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000157989.44949.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Preethee T, Kandaswamy D, Arathi G, Hannah R. Bactericidal effect of the 908 nm diode laser on Enterococcus faecalis in infected root canals. J Conserv Dent. 2012;15:46–50. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.92606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mickel AK, Nguyen TH, Chogle S. Antimicrobial activity of endodontic sealers on Enterococcus faecalis. J Endod. 2003;29:257–8. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200304000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang H, Shen Y, Ruse ND, Haapasalo M. Antibacterial activity of endodontic sealers by modified direct contact test against Enterococcus faecalis. J Endod. 2009;35:1051–5. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fouad AF, Barry J, Caimano M, Clawson M, Zhu Q, Carver R, et al. PCR-based identification of bacteria associated with endodontic infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:3223–31. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.9.3223-3231.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pizzo G, Giammanco GM, Cumbo E, Nicolosi G, Gallina G. In vitro antibacterial activity of endodontic sealers. J Dent. 2006;34:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kayaoglu G, Erten H, Alaçam T, Ørstavik D. Short-term antibacterial activity of root canal sealers towards Enterococcus faecalis. Int Endod J. 2005;38:483–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2005.00981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nawal RR, Parande M, Sehgal R, Naik A, Rao NR. A comparative evaluation of antimicrobial efficacy and flow properties for Epiphany, Guttaflow and AH-Plus sealer. Int Endod J. 2011;44:307–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2010.01829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cobankara FK, Altinöz HC, Ergani O, Kav K, Belli S. In vitro antibacterial activities of root-canal sealers by using two different methods. J Endod. 2004;30:57–60. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200401000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgental RD, Vier-Pelisser FV, Oliveira SD, Antunes FC, Cogo DM, Kopper PM. Antibacterial activity of two MTA-based root canal sealers. Int Endod J. 2011;44:1128–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2011.01931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sipert CR, Hussne RP, Nishiyama CK, Torres SA. In vitro antimicrobial activity of Fill Canal, Sealapex, Mineral Trioxide Aggregate, Portland cement and EndoRez. Int Endod J. 2005;38:539–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2005.00984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silva EJ, Rosa TP, Herrera DR, Jacinto RC, Gomes BP, Zaia AA. Evaluation of cytotoxicity and physicochemical properties of calcium silicate-based endodontic sealer MTA Fillapex. J Endod. 2013;39:274–7. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aal-Saraj AB, Ariffin Z, Masudi SM. An agar diffusion study comparing the antimicrobial activity of nanoseal with some other endodontic sealers. Aust Endod J. 2012;38:60–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4477.2010.00241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heyder M, Kranz S, Völpel A, Pfister W, Watts DC, Jandt KD, et al. Antibacterial effect of different root canal sealers on three bacterial species. Dent Mater. 2013;29:542–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gomes BP, Pedroso JA, Jacinto RC, Vianna ME, Ferraz CC, Zaia AA, et al. In vitro evaluation of the antimicrobial activity of five root canal sealers. Braz Dent J. 2004;15:30–5. doi: 10.1590/s0103-64402004000100006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Desai S, Chandler N. Calcium hydroxide-based root canal sealers: A review. J Endod. 2009;35:475–80. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou HM, Shen Y, Zheng W, Li L, Zheng YF, Haapasalo M. Physical properties of 5 root canal sealers. J Endod. 2013;39:1281–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Camargo CH, Oliveira TR, Silva GO, Rabelo SB, Valera MC, Cavalcanti BN. Setting time affects in vitro biological properties of root canal sealers. 2013;40:530–3. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2013.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orstavik D. Materials used for root canal obturation, technical, biological and clinical testing. Endod Topics. 2005;12:25–38. [Google Scholar]