Abstract

Objective:

Bleaching agents may affect the properties of dental materials. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of different polishing techniques on the surface roughness of composite resins submitted to the at-home and in-office bleaching treatment.

Materials and Methods:

Disc-shaped specimens were carried out of nanofilled and microhybrid composites (n = 10). Finishing step was performed after light curing (L1) and polishing after 24 h with two systems (L2). Then, specimens were submitted to the home or in-office bleaching procedures, and roughness was re-evaluated (L3). The surface roughness (Ra) readings were measured at L1, L2, and L3 times using a profilometer. Data were statistically analyzed by multiple-way analysis of variance and Tukey test (α = 0.05).

Results:

The polishing procedures decreased Ra for both composites compared to baseline values (L1). The roughness of specimens polished with jiffy did not present significant difference after polishing step (L2) and bleaching treatment (L3). However, the groups polished with Sof-Lex discs had increase on the Ra values after bleaching.

Conclusion:

The polishing is an important procedure to reduce the roughness of dental restorations and composite surface polished with jiffy system improved the degradation resistance to the bleaching agents compared to Sof-Lex discs.

Keywords: Composite resin, dental bleaching, surface roughness

INTRODUCTION

The demand for conservative esthetic treatments has increased substantially nowadays. Dental bleaching is a treatment that improves the appearance of teeth, and it is considered a safe procedure when well indicated and performed.[1,2,3,4] The action mechanism of bleaching agents bases on the oxidation reaction of hydrogen peroxide (HP), a substance highly unstable, which in contact with teeth and saliva releases free oxygen radicals that break the pigment molecules and the small compounds diffuse out of the tooth.[4,5]

The bleaching agent concentration depends on the technique performed, since low and high concentrations of peroxides are used in at-home and in-office bleaching, respectively.[1] Several previous studies have reported that these agents can affect the hardness, roughness, and surface morphology of dental materials and tooth enamel,[3,5,6,7,8] these consequences vary according to frequency and exposure duration.[9]

Teeth to be bleached commonly present restorations, which could be affected by bleaching agents. Currently, dental restorations are performed mainly with microhybrid and nanofilled resin-based materials, nanocomposites showed similar mechanical properties of universal hybrids and high esthetic quality.[10,11] So, situations in which the esthetics are not compromised or restoration is required before bleaching (such as noncarious lesion due to the sensitivity), repolishing of tooth-colored restorations is necessary.[12,13]

Finishing and polishing are essential steps to decrease plaque accumulation and discoloration of restorative materials; these procedures contribute to wear reduction, recurrent caries, marginal and periodontal integrity, improving the clinical longevity of dental restorations.[14,15,16] Thus, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of different polishing techniques on the surface roughness of composite resins submitted to dental bleaching procedures. The null hypotheses tested were that:

The polishing techniques,

The home-use and in-office bleaching agents, and

The different composites would not affect the roughness according to the timespan tested.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The experimental design used in this study was a randomized complete block arrangement. The factors considered were:

Material in two levels,

Polishing technique in two levels,

Bleaching agent in two levels, and

Timespan in three levels.

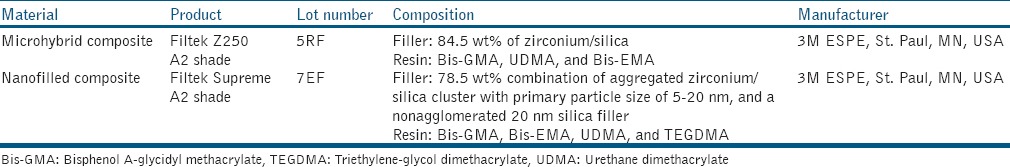

A microhybrid (Filtek Z250, 3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA) and a nanofilled (Filtek Supreme; 3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA) composite resin were evaluated [Table 1].

Table 1.

Materials used in this study

Eighty circular specimens (5 mm in diameter and 2 mm in thickness) of each material were made using a Teflon Mold. It was filled with one increment of the composite, covered with a mylar strip, and pressed with a 500-g load. Both composites were cured for 20 s in accordance with manufacturers, using a second-generation light-emitting-diode curing unit (Bluephase 16i; Vivadent, Bürs, Austria) at 1390 mW/cm2 monitored by a radiometer (model 100; Demetron/Kerr, Danbury, CT, USA).

The specimens were removed from the mold and polished with 1200-grit silicon carbide (SiC) abrasive paper (CarbiMet 2 Abrasive Discs, Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL, USA) for 30 s using a polishing machine (APL-4, Arotec S.A. Ind., and Com., Cotia, SP, Brazil), under water irrigation. Then, specimens were randomized distributed in eight groups (n = 10), according to material, polishing technique, and bleaching agent; and stored in a lightproof vial at 37°C containing artificial saliva for 24 h.

The initial surface roughness (L1) was measured using a profilometer (Surftest 211; Mitutoyo Corp., Tokyo, Japan). Each specimen was fixed in the clamping apparatus, and the profilometer meter's needle was positioned on its surface, moved at a constant speed of 0.05 mm/s, using a cut-off of 0.25 mm. Then, the arithmetical average of surface roughness (Ra) parameter was obtained. Three readings were carried out on each surface, turning the specimen in 120°, approximately. The average of these three measurements was calculated as roughness value of the specimen.

After this period, the polishing procedure was performed at low speed. For Jiff System (Ultradent Products Inc., South Jordan, UT, USA), the surface was treated for 20 s with coarse, medium, and fine (green, yellow, and white, respectively) silicon-impregnated rubber abrasive cups (Jiffy Polisher Cups), then treated for 40 s with an abrasive polishing brush (Jiffy Brush) impregnated with SiC particles. For Sof-Lex pop-on system (3M Espe, St. Paul, MN, USA) the composite surface was treated with medium, fine, and superfine aluminum oxide (Al2O3) for 20 s each disc. Then a second surface roughness reading was performed immediately after polishing step (L2), 24 h after L1.

In the home bleaching, the specimens were submitted to treatment with HP 6% White Class (FGM Dental Products, Joinville, SC, Brazil). The bleaching agent was applied covering the entire top surface 2-h daily for 2 consecutive weeks (14 days) at 37°C in relative humidity environmental (95 ± 5%), according to the manufacturers instruction. After that, the specimens were rinsed with distilled water for 1-min, dried with a soft absorbent paper, and stored in artificial saliva at 37°C for 22 h.

The specimens submitted to in-office bleaching were treated with HP 35% Whiteness HP Maxx (FGM Dental Products). Two bleaching sessions were performed with a 7-day interval between them. In each bleaching session, the three applications of 15 min (totalizing 45 min) of the bleaching agent were performed on the top surface of the specimen. After that, the specimens were rinsed with distilled water for 1 min, dried with a soft absorbent paper, and stored in artificial saliva at 37°C until next bleaching session.

After bleaching procedure, roughness was re-evaluated (L3). The normality of the data was previously analyzed by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Normal distributions were observed, so the data were statistically analyzed using multiple-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey–Kramer's test for pairwise comparisons (α = 0.05). The four factors in the study were: composite resin, polishing technique, bleaching agent, and timespan. The roughness was performed on the same specimen in different evaluation times. Therefore, these data were compared by the ANOVA for repeated measure with proc mixed tool of SAS statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

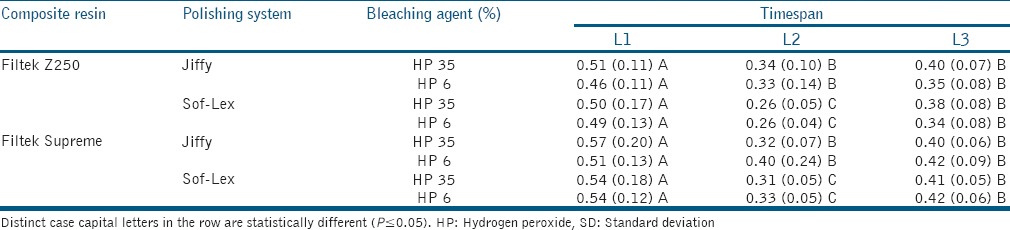

ANOVA showed statistical difference only for the factor timespan among roughness readings (P < 0.0001). The polishing procedures decreased surface roughness for both composite resins compared to baseline values (L1). The roughness of the specimens polished with jiffy system did not present statistical difference after polishing step (L2) and bleaching treatment (L3). However, the groups polished with Sof-Lex discs had an increase on the surface roughness after bleaching. This findings are showed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Surface roughness (Ra, μm) mean (SD) according to composite resin, polishing system, bleaching agent, and timespan

DISCUSSION

The present investigation evaluated the surface roughness of microhybrid and nanofilled composite resins after different polishing techniques and at-home and in-office bleaching procedures. Restoration polishing is an important clinical procedure to obtain final smoothness surface, reducing plaque retention, and staining susceptibility.[14,15,16] Several polishing systems can be used, such as prophylaxis and polishing pastes, stones, tungsten, carbide burs, fine and superfine diamond burs, abrasive discs, abrasive points, soft rubber cup, diamond impregnated felt, brushes with abrasive bristles, and combination of these instruments.[17]

In this study, after light curing the specimens were grounded with 1200-grit SiC abrasive paper under water irrigation to simulate clinical finishing step.[17] In clinical practice, this procedure is required to remove material excess and resin-rich layer on the top surface and improve restoration contouring.[14,17,18] The polishing procedure was performed after 24 h and decreased the surface roughness of both composites, but after bleaching treatment the Ra values increased only for the specimens polished with Sof-Lex system, thus the first null hypothesis was rejected. One possible explanation for this could be related to the composition of polishing systems.

Jiffy polishers and brush are impregnated with SiC particles to provide composite polishing, while Sof-Lex discs are impregnated with Al2O3 particles.[14,19] However, the hardness of the abrasive SiC is higher than Al2O3 (www.rundum.co.jp/e/product/index6.html), which can generate similar roughness values, since this also depends of abrasive particle size, but with different wear capacity on load particles of the surface without released it. In addition, despite both polishing systems produced smoothest surfaces, a jiffy is more advantageous clinically because accesses areas that not readily accessible to discs.[14]

At-home and in-office techniques used bleaching agents of low and high concentration, respectively.[1] The two HP concentrations increased the surface roughness for both composite resins when the polishing was performed with Sof-Lex, thus the second null hypothesis also was rejected. This fact could be explain by the de-bonding of fillers from resin matrix by water uptake and stress corrosion cracking due to the action of free radicals generated during bleaching can have an adverse effect on the resinous matrix–filler interface.[12] Probably this interface was more affected by the polishing with Sof-Lex and bleaching agent contact resulted in the highest surface degradation.

The active bleach agent (HP) is very unstable, its high oxidative capacity may cause adverse consequences for both organic and inorganic structures of resin-based composites. When the peroxide contacts with organic components of the composite it impairs the polymer linkages that form the network structure, besides causing alterations in the inorganic phase, reducing the long-term material performance.[5] However, bleaching agents did not affect the roughness of the specimens polished with jiffy system.

The surface roughness comparing nanofilled and microhybrid composites resins were similar; therefore the third null hypothesis was accepted. Previous studies have been observed that nanocomposites showed excellent surface quality, such as high polish and polish retention, similar to microfill, maintaining physical properties and wear resistance equivalent to the traditional composites.[10,11] However, both composite resins after polishing reduced the roughness, showing similar Ra values.

Several studies have shown that the performance of different composite resins is strongly influenced by the monomer composition.[7,20] During bleaching the oxidation process on the resinous matrix facilitates water sorption and leads to loss of particles, increasing superficial degradation and leading to gloss loss.[12,21] The composition of the organic matrix of both resin-based materials evaluated is similar, showing similar behavior after bleaching. Therefore, it can be speculated that probably the damage was more evident on the resin matrix, filler content, and the interface between the organic matrix and filler due to the higher surface change caused by Sof-Lex polishing.

Usually, anterior restorations are replaced after dental bleaching to improve shade matching. In situations such as deep cavities arising from noncarious lesions that warrant restoration and defective restorations that need to be repaired or replaced prior to bleaching procedures, the clinician can opt for lighter shades so that the restorations match better. This also applies to posterior restorations in which color match is not critical. Therefore, others properties should be investigated for better decision if replacement or repolishing of dental composite restorations is really necessary after bleaching procedures.

CONCLUSION

According to the results of this in vitro study, the following conclusions were drawn: the polishing procedure is an important step to decrease the roughness of dental restorations, both home-use and in-office bleaching techniques can increase the surface roughness of the composite resins, and the composite surface polished with jiffy system improved the degradation resistance to the bleaching agents compared to Sof-Lex discs.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported by PIBIC/CNPq (08-2010/07-2011).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by PIBIC/CNPq (08-2010/07-2011).

REFERENCES

- 1.Moraes RR, Marimon JL, Schneider LF, Correr Sobrinho L, Camacho GB, Bueno M. Carbamide peroxide bleaching agents: Effects on surface roughness of enamel, composite and porcelain. Clin Oral Investig. 2006;10:23–8. doi: 10.1007/s00784-005-0016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abd Elhamid M, Mosallam R. Effect of bleaching versus repolishing on colour and surface topography of stained resin composite. Aust Dent J. 2010;55:390–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2010.01259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang L, Francisconi LF, Atta MT, Dos Santos JR, Del Padre NC, Gonini A, Jr, et al. Effect of bleaching gels on surface roughness of nanofilled composite resins. Eur J Dent. 2011;5:173–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Araújo LS, dos Santos PH, Anchieta RB, Catelan A, Fraga Briso AL, Fraga Zaze AC, et al. Mineral loss and color change of enamel after bleaching and staining solutions combination. J Biomed Opt. 2013;18:108004. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.18.10.108004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lima DA, De Alexandre RS, Martins AC, Aguiar FH, Ambrosano GM, Lovadino JR. Effect of curing lights and bleaching agents on physical properties of a hybrid composite resin. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2008;20:266–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2008.00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pinto CF, Oliveira RD, Cavalli V, Giannini M. Peroxide bleaching agent effects on enamel surface microhardness, roughness and morphology. Braz Oral Res. 2004;18:306–11. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242004000400006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosentritt M, Lang R, Plein T, Behr M, Handel G. Discoloration of restorative materials after bleaching application. Quintessence Int. 2005;36:33–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zuryati AG, Qian OQ, Dasmawati M. Effects of home bleaching on surface hardness and surface roughness of an experimental nanocomposite. J Conserv Dent. 2013;16:356–61. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.114362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Attin T, Hannig C, Wiegand A, Attin R. Effect of bleaching on restorative materials and restorations — A systematic review. Dent Mater. 2004;20:852–61. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitra SB, Wu D, Holmes BN. An application of nanotechnology in advanced dental materials. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:1382–90. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beun S, Glorieux T, Devaux J, Vreven J, Leloup G. Characterization of nanofilled compared to universal and microfilled composites. Dent Mater. 2007;23:51–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wattanapayungkul P, Yap AU, Chooi KW, Lee MF, Selamat RS, Zhou RD. The effect of home bleaching agents on the surface roughness of tooth-colored restoratives with time. Oper Dent. 2004;29:398–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polydorou O, Hellwig E, Auschill TM. The effect of different bleaching agents on the surface texture of restorative materials. Oper Dent. 2006;31:473–80. doi: 10.2341/05-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borges AB, Marsilio AL, Pagani C, Rodrigues JR. Surface roughness of packable composite resins polished with various systems. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2004;16:42–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2004.tb00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yazici AR, Tuncer D, Antonson S, Onen A, Kilinc E. Effects of delayed finishing/polishing on surface roughness, hardness and gloss of tooth-coloured restorative materials. Eur J Dent. 2010;4:50–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rai R, Gupta R. In vitro evaluation of the effect of two finishing and polishing systems on four esthetic restorative materials. J Conserv Dent. 2013;16:564–7. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.120946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.St-Georges AJ, Bolla M, Fortin D, Muller-Bolla M, Thompson JY, Stamatiades PJ. Surface finish produced on three resin composites by new polishing systems. Oper Dent. 2005;30:593–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Setcos JC, Tarim B, Suzuki S. Surface finish produced on resin composites by new polishing systems. Quintessence Int. 1999;30:169–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roeder LB, Tate WH, Powers JM. Effect of finishing and polishing procedures on the surface roughness of packable composites. Oper Dent. 2000;25:534–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gurgan S, Yalcin F. The effect of 2 different bleaching regimens on the surface roughness and hardness of tooth-colored restorative materials. Quintessence Int. 2007;38:e83–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yalcin F, Gürgan S. Effect of two different bleaching regimens on the gloss of tooth colored restorative materials. Dent Mater. 2005;21:464–8. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]