Abstract

Acute acalculous cholecystitis (AAC) is a rare complication of Epstein Barr virus (EBV) infection, with only a few cases reported among pediatric population. This clinical condition is frequently associated with a favorable outcome and, usually, a surgical intervention is not required. We report a 16-year-old girl who presented with AAC following primary EBV infection. The diagnosis of AAC was documented by clinical and ultrasonographic examination, whereas EBV infection was confirmed serologically. A conservative treatment was performed, with a careful monitoring and serial ultrasonographic examinations, which led to the clinical improvement of the patient. Pediatricians should be aware of the possible association between EBV and AAC, in order to offer the patients an appropriate management strategy.

Key words: Acute acalculous cholecystitis, Epstein-Barr virus, primary infection, adolescent

Introduction

Epstein Barr virus (EBV) infection has a worldwide distribution and a high prevalence among adult population, with more than 90% seropositivity.1 Acute infection with EBV during childhood is common but mainly asymptomatic, whereas it presents as typical infectious mononucleosis with clinical signs such as fever, pharyngitis, cervical lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly and hepatocellular dysfunction in at least 50% of adolescents and young adults with primary infection.1,2

Acute acalculous cholecystitis (AAC) is an inflammation of the gallbladder, in the absence of gallstones, which is usually associated with more serious morbidity and higher mortality rates than calculus cholecystitis.3 AAC complicating the course of acute EBV infection has been rarely described in pediatric population. We report the case of an adolescent girl with AAC due to primary EBV infection.

Case Report

A 16-year-old Caucasian female was admitted to our hospital with a 8-day history of fever (39.1°C), and a 5-day history of bilateral periorbital edema, anorexia, nausea, and right upper quadrant abdominal pain. Her past medical history was unremarkable, apart from an episode of allergic rhinitis. No relevant family history was identified.

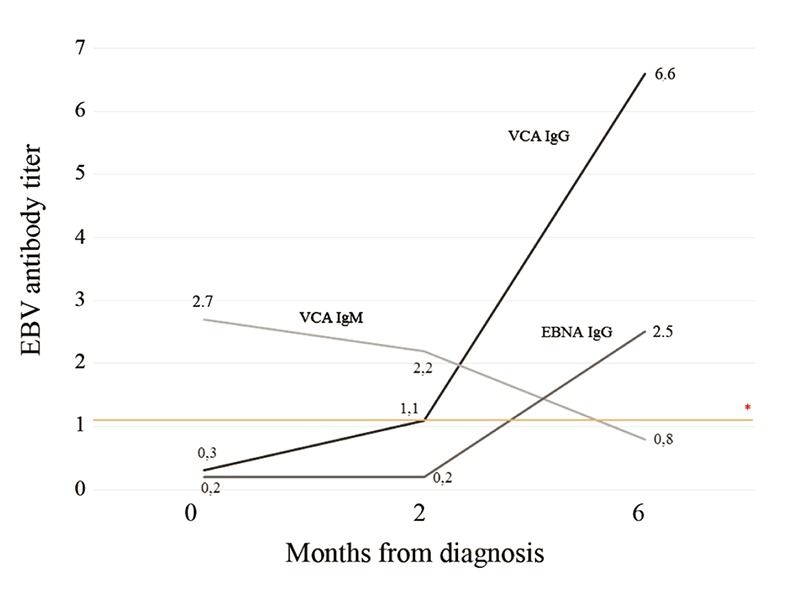

Physical examination showed a bilateral periorbital edema. Bilateral cervical adenopathy were noticed, with the largest nodes measuring 1.5 cm in diameter. Abdominal examination revealed a non-distended abdomen, with normally active bowel sounds and mild tenderness localized over the right hypochondrium. There was no hepatosplenomegaly or evidence of free fluid in the abdomen. Scleral icterus was not present and the remaining physical findings were normal. Laboratory investigations on admission revealed a hemoglobin level of 13.3 g/dL, hematocrit of 41.5%, platelet count of 197×109/L and white blood cell count of 10.1×109/L (neutrophils 20%, lymphocytes 61%). Atypical lymphocytes were noted (13%) on peripheral blood smear. Liver enzymes were elevated: aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, and gamma-glutamyltransferase were 340, 689, 224, and 271 UI/L, respectively. Total bilirubin was 0.7 mg/dL, with a direct fraction of 0.3 mg/dL. The coagulation profile was normal. Other laboratory data showed a glucose level of 4.0 mmol/L, total protein 78 g/L, albumin 37 g/L, amylase 66 U/L, lipase 165 U/L, and C-reactive protein 7.1 mg/L. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed a moderately distended gallbladder with a striated thickened wall measuring 9 mm. There was no evidence of stones or dilatation of the biliary tract. These findings in combination with clinical and laboratory data were compatible with the diagnosis of AAC. Oral feeding was stopped and intravenous fluids were started. Furthermore, broad spectrum antibiotic (cefoxitin and clindamycin) treatment was started. On the third hospital day, she continued to be febrile with no improvement in her abdominal pain despite the established treatment. The liver became palpable 3 cm under the costal margin, and prominent tonsillar enlargement with exudates was noticed. The liver enzyme levels increased (aspartate aminotransferase 721 UI/L, alanine aminotransferase 409 UI/L, alkaline phosphatase 365 UI/L, gamma-glutamyltransferase 330 UI/L) with a persistent lymphocytosis (70-75%) showed in the repeated blood counts. Follow-up ultrasonographic examination did not reveal any worsening of the cholecystitis. Infectious mononucleosis was suspected as a cause of acalculous cholecystitis and the following EBV panel results were indicative of acute primary infection (Figure 1). Further diagnostic work-up, including blood, urine and stool cultures were negative and no group A streptococci infection was identified. The serological tests performed for hepatitis A, B, and C viruses, cytomegalovirus, human immunodeficiency virus, adenovirus, enterovirus, Brucella species, Leptospira species, Clamydia species, Mycoplasma species, Rickettsia rickettsii and Coxiella burnetii were all negative. Once the diagnosis of primary EBV infection was confirmed, the antibiotics were discontinued. On the fifth hospital day, the fever resolved and the appetite and abdominal pain gradually improved. Repeated ultrasonographic examinations showed a progressive regression of the abnormal findings previously observed. The patient was discharged 12 days after admission and during a follow-up of 7 months, she has been in good condition without any sign of recurrence. All liver chemistry abnormalities and abdominal ultrasonographic returned to normal limits two months after admission. EBV seroconversion was documented six months after discharge, with the appearance of positive VCA-IgG and EBNA-IgG antibodies, confirming the diagnosis of EBV primary infection (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Evolution of EBV antigens titers measured in the patient at diagnosis, 2 and 6 months after diagnosis. (VCA) - Viral capsid antigen; (EBNA) - EBV nuclear antigen *The positive values of EBV VCA IgM, VCA IgG and EBNA IgG were defined as ≥1.10.

Discussion

Gallbladder disease is rare among pediatric population. It is estimated that 1.3 pediatric cases occur each 1000 adult cases.4

AAC comprises approximately 5 to 10% of all cases of acute cholecystitis in adults and is even less frequently diagnosed in children.3 It is most commonly observed in ill patients, following major cardiac and abdominal surgery, severe trauma, burns, prolonged fasting and long-term total parenteral nutrition.5 It has also been associated with systemic diseases such as Kawasaki disease and polyarteritis nodosa.6,7

In children, AAC occurs more frequently during the course of infectious diseases such as sepsis, gastroenteritis (including Vibrio cholerae, Salmonella, Shigella, and Giardia lamblia), pneumonia (especially that caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae), cytomegalovirus primary infection, hepatitis A, Dengue, infection secondary to non-tuberculous mycobacteria, leptospirosis, Q-fever, Candida, malaria and as a late complication of HIV infection.5,7 AAC complicating the course of primary EBV infection has been rarely reported in pediatric population. Reviewing the literature, we found 17 pediatric cases (<18yo) of AAC, published between 2004 and 2015, in the context of EBV primary infection (Table 1).6-19 Most of them occurred in female patients (15 out of 17).

| Authors, year | Country | Age | Sex | Symptoms and clinical signs | ALT/AST (UI/L) | GGT/ALP (UI/L) | TB (DB) (mg/dL) | WBC (x 109/L) | L (atypical) (%) | CRP (mg/L) | Ultrasonographic findings in the GB | Antibiotic | Surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yoshie et al., 20048 | Japan | 15 | F | Fever, abdominal pain (positive MS), cervical adenopathy, splenomegaly | 569/215 | -/- | -(-) | 11 | 73 (-) | Wall thickening (10 mm) | - | - | |

| Lagona et al., 20079 | Greece | 4 | F | Fever (4 d), malaise, vomiting, abdominal pain (positive MS), hepatosplenomegaly, scleral icterus, exudative tonsillopharyngitis, cervical adenopathy | 304/188 | 241/236 | 4.6 (3.6) | 22.1 | - (25) | 8 | Wall thickening (9 mm), sludge, positive SMS | No | No |

| Prassouli et al., 200710 | Greece | 13 | F | Fever (5 d), malaise, vomiting, RUQ abdominal pain (positive MS), jaundice, pharyngitis, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly*, exudative tonsillopharyngitis*, cervical adenopathy* | 674/394 | 352/721 | 4 (3.5) | 13.8 | 53(15) | 37 | Wall thickening (13.6 mm), intramular striations, sludge, positive SMS | Yes (7d) | No |

| Gora-Gebka et al., 200811 | Poland | 9 | F | Fever (6 d), malaise, abdominal pain (positive MS), hepatosplenomegaly, pharyngitis, cervical adenopathy, diarrhea, petechial rash (limbs), jaundice | 179/- | 182/629 | 4.65 (2.5) | 21.2 | 44 (-) | 47.3 | Wall thickening (9 mm), intramural striations, pericholecysticfluid collection | Yes | No |

| Gora-Gebka et al., 200811 | Poland | 4 | F | Fever (7 d), RUQ abdominal pain, jaundice, hepatosplenomegaly, | 423/388 | 301/752 | 2.89 (1.6) | 25.9 | 22(62) | 18.8 | Wall thickening (7 mm), intramural striations acholic stools | Yes | No |

| Pelliccia et al., 200812 | Italy | 14 | F | Fever, cervical adenopathy, pharyngitis, abdominal pain (positive MS), hepatosplenomegaly | 108/- | -/- | -(-) | - | 72 (-) | - | Wall thickening (10 mm) | No | No |

| Attilakos et al., 200913 | Greece | 5 | M | Fever (7 d), sore throat, malaise, scleral icterus, exsudative tonsillopharyngitis, cervical adenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly | 257/207 | 333/919 | 1.8 (0.9) | 23.3 | - (10) | 13 | Wall thickening (4.2 mm), striations, positive SMS | No | No |

| Attilakos et al., 200913 | Greece | 4 | F | Fever (4 d), malaise, vomiting, RUQ abdominal pain, scleral icterus, exsudative tonsillopharynghitis, cervical adenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly | 304/188 | 241/236 | 4.6 (3.6) | 22.1 | - (25) | 8 | Wall thickening (9 mm), sludge, positive SMS | No | No |

| Arya et al., 20107 | USA | 16 | F | Fever (7 d), malaise, vomiting, RUQ abdominal pain (positive MS), jaundice, pharyngitis, exudative tonsillopharyngitis* | 479/211 | 173/458 | 8.5 (5.2) | 13.2 | - (81) | - | Wall thickening (9 mm), pericholecystic edema | Yes* | No |

| Aydin Teke et al., 201314 | Turkey | 8 | F | Fever (7 d), vomiting, RUQ abdominal pain, exudative tonsillopharyngitis, cervical adenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly | 496/569 | 103/434 | 4.6 (3.2) | 10.2 | 74 (-) | - | Wall thickening, GB distention | No | No |

| Fretzayas et al., 201415 | Greece | 11 | F | Fever (2 d), facial edema (eyelids), pharyngitis, hepatosplenomegaly, cervical adenopathy, positive MS* | 198/291 | 52/536 | 1.8 (0.4) | 14.6 | 70 (-) | 5 | Wall thickening (7.3 mm) | - | No |

| Fretzayas et al., 201415 | Greece | 12 | F | Fever (3 d), coryza, cough, abdominal pain, hepatosplenomegaly, facial edema (eyelids) | 125/134 | 162/- | -(-) | 4.9 | 53 (-) | 11 | Wall thickening (9 mm), striations, sludge | - | No |

| Kim et al, 20146 | Korea | 10 | F | Fever (1 d), malaise, RUQ abdominal pain (positive MS), cervical adenopathy | 489/311 | 308/- | 1 (0.6) | 8.2 | 56(1) | 4 | Wall Thickening (6 mm), positive SMS | Yes | No |

| Poddighe et al., 201416 | Italy# | 7 | F | RUQ abdominal pain (positive MS), hepatomegaly, vomiting, jaundice, pharyngitis | 3324/3398 | 143/- | 8.9 (5.06) | 8.5 | - (-) | 3.5 | Wall thickening (10 mm), sludge, pericolecystic | fluidYes* | No |

| Suga et al., 201417 | Japan | 6 | F | Fever (10 d), facial edema (eyelids), cervical adenopathy, pharynghitis, abdominal pain (positive MS) | 139/184 | 36/506 | 0.4 (0.1) | 13.6 | - (-) | 6 | Wall thickening (4.6 mm), sludge, pericholecystic fluid, positive SMS | Yes | No |

| Alkhoury et al., 201518 | USA | 15 | F | Fever (3 d), malaise, vomiting, abdominal pain, cough, headache | 221/191 | -/221 | 2.3 (1.8) | 10.9 | 59 (-) | - | Wall thickening (19 mm), pericholecystic fluid | No | No |

| Shah et al., 201519 | USA | 6 | M | Fever (6 d), malaise, vomiting, abdominal pain (positive MS), splenomegaly | 331/135 | 180/569 | 2.3 (1.5) | 18.2 | 80 (-) | - | Wall thickening (8 mm), GB distention, sludge | Yes (8d) | No |

| Present case | Portugal | 16 | F | Fever (8 d), facial edema (periorbital), malaise, RUQ abdominal pain, cervical adenopathy, hepatomegaly*, exudative tonsillopharyngitis* | 409/721 | 330/365 | 0.7 (0,3) | 10.1 | 61(13) | 7.1 | Wall thickening (9 mm), GB distention, striation | Yes* | No |

ALT: alanine aminotransferase, ALP: alkaline phosphatase, GGT: Gamma-glutamyltransferase; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; TB: total bilirubin; DB: direct bilirubin; WBC: white blood cells, L: Lymphocytes, CRP: C-reactive protein; GB: gallbladder; F:female; M: male; MS: Murphy’s sign; d: days; RUQ: right upper quadrant; SMS: sonographic Murphy’s sign

*Symptoms and clinical signs developed during hospital stay; discontinued after diagnosis of primary Esptein-Barr virus infection

#Born in Parkistan.

The exact pathogenesis of AAC in EBV primary infection remains unclear. The direct invasion of the gallbladder mucosa and bile stasis have been both proposed as a possible mechanism leading to gallbladder inflammation and subsequent AAC.10

The clinical presentation and laboratory data of AAC in children are nonspecific and are similar to those seen in adult.6 Abdominal ultrasonography is the main diagnostic criterion for AAC and the typical ultrasonographic findings include gallbladder wall thickening over 3 mm, distention of the gallbladder, striated gallbladder wall, localized tenderness (sonographic Murphy’s sign), and pericholecystic fluid and sludge.10-13 The combination of two or more of the above-mentioned findings, in the appropriate clinical setting, is considered to be diagnostic.2,5

In our case, the patient initially presented with fever, nausea and pain in the right hypochondrium. This clinical onset, in association with the presence of ultrasonographic findings, such as the distension of the gallbladder with a striated and thickened wall (9 mm), the absence of stones and the dilatation of the biliary tract supported the diagnosis of ACC. During her hospitalization, she also developed the typical features of infectious mononucleosis with an acute EBV infection confirmed by serological tests. It is commonly known that the two main treatment options for AAC are cholecystectomy and cholecystostomy.3 In children, however, nonoperative treatment is safe and effective in most cases.6 Emergency operative intervention is considered only when the previously determined ultrasonographic criteria deteriorate or persist on follow-up ultrasonographic examination.10

Usually, AAC secondary to EBV primary infection has a positive prognosis. In fact, all the pediatric cases reported had favorable outcomes (Table 1). The patients were monitored closely with serial ultrasonographic examinations, where progressive regression of the abnormal findings was documented, simultaneously with the improvement of patient’s clinical condition. The antibiotics were discontinued after the diagnosis of EBV primary infection and no surgical intervention was required.6-18

Conclusions

In summary, despite being a rare entity in the pediatric population, clinicians should be aware of the possible occurrence of AAC during EBV primary infection. It is important to keep a high index of suspicion for the diagnosis of this condition, especially when confronted by a young patient without relevant past history and presenting an AAC, in order to avoid overuse of antibiotics or unnecessary invasive procedures.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the young patient and her family for their cooperation and consent for publication.

References

- 1.Macsween KF, Crawford DH. Epstein-Barr virus-recent advances. Lancet Infect Dis 2003;3:131-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jenson H. Epstein Barr-virus. Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 17th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004. pp 1062-6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barie PS, Eachempati SR. Acute acalculous cholecystitis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2003;5:302-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arroyo AC. Hepatobiliary. Doniger SJ, eds. Pediatric emergency critical care and ultrasound. 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2013. pp 160-77. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barie PS, Eachempati SR. Acute acalculous cholecystitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2010;39:343-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim A, Yang HR, Moon JS, et al. Epstein-Barr virus infection with acute acalculous cholecystitis. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr 2014;17:57-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arya SO, Saini A, El-Baba M, et al. Epstein Barr virus-associated acute acalculous cholecystitis: a rare occurrence but favorable outcome. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2010;49:799-804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoshie K, Ohta M, Okabe N, et al. Gallbladder wall thickening associated with infectious mononucleosis. Abdom Imaging 2004;29:694-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lagona E, Sharifi F, Voutsioti A, et al. Epstein-Barr virus infectious mononucleosis associated with acute acalculous cholecystitis. Infection 2007;35:118-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prassouli A, Panagiotou J, Vakaki M, et al. Acute acalculous cholecystitis as the initial presentation of primary Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Pediatr Surg 2007;42:E11-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gora-Gebka M, Liberek A, Bako W, et al. Acute acalculous cholecystitis of viral etiology: a rare condition in children? J Pediatr Surg 2008;43:e25-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pelliccia P, Savino A, Cecamore C, et al. Imaging spectrum of EBV-infection in a young patient. J Ultrasound 2008;11:82-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Attilakos A, Prassouli A, Hadjigeorgiou G, et al. Acute acalculous cholecystitis in children with Epstein-Barr virus infection: a role for Gilbert’s syndrome? Int J Infect Dis 2009;13:e161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aydin Teke T, Tanir G, Ozel A, et al. A case of acute acalculous cholecystitis during the course of reactive Epstein-Barr virus infection. Turk J Gastroenterol 2013;24:571-2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fretzayas A, Moustaki M, Attilakos A, et al. Acalculous cholecystitis or biliary dyskinesia for Epstein-Barr virus gallbladder involvement? Prague Med Rep 2014;115:67-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poddighe D, Cagnoli G, Mastricci N, Bruni P. Acute acalculous cholecystitis associated with severe EBV hepatitis in an immunocompetent child. BMJ Case Rep 2014;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suga K, Shono M, Goji A, et al. A case of acute acalculous cholecystitis complicated by primary Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Med Invest 2014;61:426-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alkhoury F, Diaz D, Hidalgo J. Acute acalculous cholecystitis (AAC) in the pediatric population associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection. Case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep 2015;11:50-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah S, Schroeder S. A rare case of primary EBV infection causing acute acalculous cholecystitis. J Ped Surg Case Reports 2015;3:285-8. [Google Scholar]