Abstract

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare, clonal proliferative disorder of Langerhans’ cells of unknown etiology. Although the clinical presentation and therapeutic approach to the disease in children have been well established; limited data is available about the disease in adults. Purely cutaneous involvement of LCH in a man older than 70 years has rarely been described. Herein we report the case of a 71-year-old man with cutaneous LCH confined to the perioral region, scalp, and flexures successfully treated with thalidomide.

Keywords: Cutaneous, elderly, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, perioral lesion, thalidomide

INTRODUCTION

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a group of histiocytic disorders characterized by proliferation of Langerhans’ cells (LC) with several grades of tissue infiltration and systemic involvement.[1] Several tissues may be involved simultaneously: Bones, lungs, skin, oral–genital mucosa, and endocrine glands.[2] Although the skin is a common target, purely cutaneous forms of LCH with adult onset have been described very rarely in the literature.[3] We report a case of purely cutaneous LCH in a 71-year-old man with no other signs of systemic involvement. Skin involvement in LCH as a single system disease can be treated with psoralen ultraviolet A therapy (PUVA), methotrexate, thalidomide, or azathioprine.[3,4]

CASE REPORT

A 71-year-old man presented with a one month history of multiple painful ulcers around perioral region and rashes in the flexural areas, with pain and difficulty in swallowing. The patient denied systemic symptoms such as fever, fatigue, vomiting, diarrhea, polyuria, dyspnea, or bone pain.

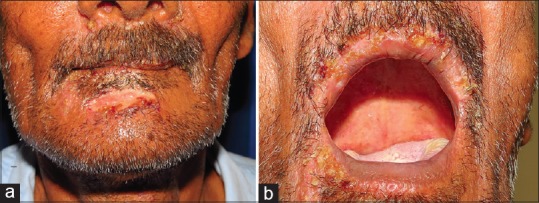

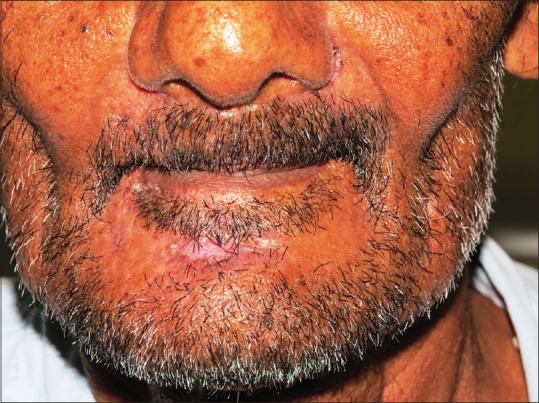

Dermatologic examination revealed a single, well-defined, tender, oval 4 × 2 cm ulcer with sloping edges and crusting over the chin with multiple, crusted perioral ulcers arranged around the margins of the lips [Figure 1a and b] and minimal, erythematous, crusted erosions over bilateral axillae, groins, and scalp (temporal, parietal, and occipital areas) [Figure 2a–c]. He also had painful oral ulcers. There was no regional or generalized lymphadenopathy or organomegaly. Differential diagnoses considered were seborrheic dermatitis with secondary infection, echthyma, orificial tuberculosis, LCH, intertrigo, candidiasis, and Hailey–Hailey disease.

Figure 1.

(a) Ulcer over the chin; (b) Crusted ulcers over the upper lip

Figure 2.

(a) Erosions over the scalp; (b) erosions over theaxillae; and (c) erosions over the groins

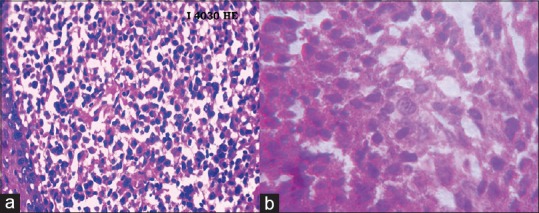

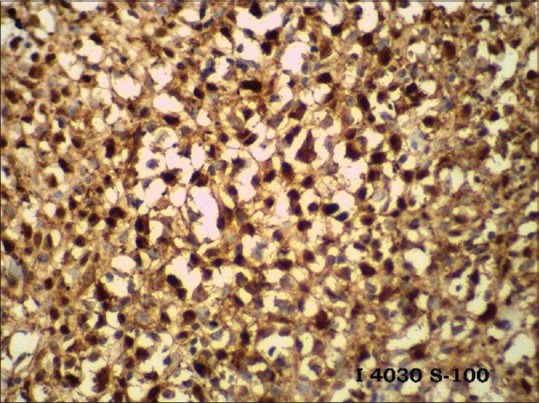

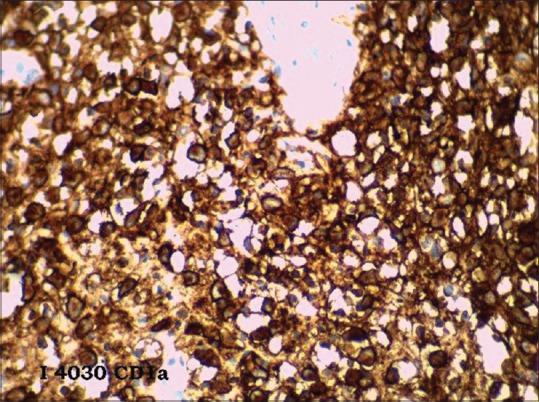

Histological examination of the affected skin revealed a diffuse, superficial, and deep dermal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, with a predominance of cells showing pale cytoplasm and kidney-shaped nuclei [Figure 3]. Immunohistochemistry revealed the nature of the infiltrating cells, which showed a diffuse expression of S-100 [Figure 4] and CD la [Figure 5] confirming the diagnosis of LCH.

Figure 3.

(a and b) Rich dermal infiltrate with large histiocytes with reniform nucleus (H and E ×100 and ×400)

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry, S100 positivity (×400)

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry, CD1a positivity (×400)

Routine urine analysis, biochemical investigations, complete blood count, abdominal ultrasonography, chest radiography, and contrast-enhanced computed tomography chest were within normal limits, except hemoglobin, which was 9.5gm%. Complete skeletal survey done was normal and no pathological findings were detected upon bone marrow biopsy. Overall, the clinical, laboratory, histological, and immunohistochemistry findings fulfilled the criteria for diagnosis of cutaneous LCH of adult onset, according to the 2013 guidelines of the Histiocyte Society.[4]

Thalidomide was initiated in a dose of 100 mg once daily, increased to 200 mg once daily at night after one week. Six weeks after starting thalidomide, dramatic improvement was noted, and the lesions completely healed [Figure 6] and thalidomide was tapered to a maintenance dose of 50 mg on alternate days. No adverse effects of thalidomide were seen during the course of the treatment and thalidomide was stopped after 10 months. Thalidomide has an added advantage in that it does not lead to the development of malignancies such as leukemia, unlike chemotherapeutic agents. The individual remained asymptomatic at 12 months follow up.

Figure 6.

Complete healing of ulcer on the chin and perioral ulcers after six weeks of thalidomide

DISCUSSION

The incidence of LCH in adults is 1–2 cases per million[5] and although the skin represents the second most commonly involved organ in single system disease after the bones,[2] the prevalence of LCH confined to the skin ranged from 4.4% to 7.01% of cases.[5] Moreover, only 2% of patients with LCH, either multisystem or localized, are older than 70 years.[6]

LCH is a group of idiopathic histiocytic disorders including a wide spectrum of diseases with different clinical features and prognosis, whose classification into separate entities, namely, Letterer–Siwe disease, Hand–Schuller–Christian disease, Hashimoto–Pritzker disease and eosinophilic granuloma is only of historical interest.[6] The Histiocyte Society has proposed a newer classification of LCH in 2013.[3] According to the organ involvement, LCH may be classified into a localized (“single-system disease”) or a disseminated disease (“multisystem disease”), which may be further distinguished into two clinical variants with different course and prognosis (“low-risk” and “high-risk” groups).[3] In adults, the cutaneous manifestations include an erosive intertriginous eruption resembling a deficiency dermatitis or seborrheic dermatitis, xanthomatous eruptions, or acneiform eruptions.[6] Atypical presentations of LCH include purely cutaneous manifestations in elderly patients, isolated tonsillar involvement, and paronychia. LCH may also manifest as papules, pustules, vesicles, petichiae, or purpura.[7]

The laboratory tests to be performed for all patients independent of the affected organs include a complete blood count, blood chemistry, coagulation studies, thyroid function tests, and urine analysis. A skeletal survey, skull series, and chest radiography (anteroposterior and lateral) are the first radiographic examinations to be done. Further investigations may be indicated based on the patient's symptoms and the findings of the basic diagnostic tests.

Treatment of cutaneous LCH is controversial. Several therapeutic approaches have been reported in the literature, according to the extent of disease - topical and systemic corticosteroids, topical imiquimod, PUVA, thalidomide, INFa-2b. vinblastine, and surgery.[3] The reported prognosis in elderly patients with single-system disease involving the skin is controversial.[8] Despite its benign nature, cutaneous LCH is generally associated with a poor therapeutic response[9] and it tends to recur, thus patients may progress toward multisystem disease.[8]

Thalidomide is an anti-inflammatory, antiangiogenic, and immunomodulatory compound that decreases the level of cytokines and TNF-α. The proliferation and production of Langerhans cells from hematopoietic stem cells is promoted by TNF-α.[8] Therefore, thalidomide can treat LCH by inhibiting the production of TNF-α. Thalidomide has been used successfully for treatment of localized LCH, such as perioral lesions, genital, and disseminated skin lesions.[8] Earlier case studies have reported dramatic responses of both cutaneous and anogenital lesions to thalidomide.[8,10,11] Our case was treated with thalidomide and after six weeks, the lesions had completely resolved.

Interesting aspects of this case is the rarity of a purely cutaneous form of LCH presenting as an ulcer on the chin in a 71-year-old man and the dramatic response to thalidomide.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stockschlaeder M, Sucker C. Adult Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Eur J Haematol. 2006;76:363–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2006.00648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aydogan K, Tunali S, Koran Karadogan S, Balaban Adim S, Turan H. Adult-onset Langerhans cell histiocytosis confined to the skin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:890–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Girschikofsky M, Arico M, Castillo D, Chu A, Doberauer C, Fichter J, et al. Management of adult patients with Langerhans cell histiocytosis: Recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of Euro-Histio-Net. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:72. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imanaka A, Tarutani M, Itoh H, Kira M, Itami S. Langerhans cell histiocytosis involving the skin of an elderly woman: A satisfactory remission with oral prednisolone alone. J Dermatol. 2004;31:1023–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2004.tb00648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aricó M, Girschikofsky M, Généreau T, Klersy C, McClain K, Grois N, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in adults. Report from the International Registry of the Histiocyte Society. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:2341–8. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(03)00672-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2011. Andrew's Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology; pp. 707–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newman B, Hu W, Nigro K, Gilliam AC. Aggressive histiocytic disorders that can involve the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:302–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sander CS, Kaatz M, Elsner P. Successful treatment of cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis with thalidomide. Dermatology. 2004;208:149–52. doi: 10.1159/000076491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li R, Lin T, Gu H, Zhou Z. Successful thalidomide treatment of adult solitary perianal Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:391–2. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2010.0905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shahidi-Dadras M, Saeedi M, Shakoei S, Ayatollahi A. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: An uncommon presentation, successfully treated by thalidomide. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:587–90. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.84064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meunier L, Marck Y, Ribeyre C, Meynadier J. Adult cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis: Remission with thalidomide treatment. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:168. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb08659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]