Abstract

Background

Recent findings have reemphasized the importance of epistasis, or gene-gene interactions, as a contributing factor to the unexplained heritability of obesity. Network-based methods such as statistical epistasis networks (SEN), present an intuitive framework to address the computational challenge of studying pairwise interactions between thousands of genetic variants. In this study, we aimed to analyze pairwise interactions that are associated with Body Mass Index (BMI) between SNPs from twelve genes robustly associated with obesity (BDNF, ETV5, FAIM2, FTO, GNPDA2, KCTD15, MC4R, MTCH2, NEGR1, SEC16B, SH2B1, and TMEM18).

Methods

We used information gain measures to identify all SNP-SNP interactions among and between these genes that were related to obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2) within the Framingham Heart Study Cohort; interactions exceeding a certain threshold were used to build an SEN. We also quantified whether interactions tend to occur more between SNPs from the same gene (dyadicity) or between SNPs from different genes (heterophilicity).

Results

We identified a highly connected SEN of 709 SNPs and 1241 SNP-SNP interactions. Combining the SEN framework with dyadicity and heterophilicity analyses, we found 1 dyadic gene (TMEM18, P-value = 0.047) and 3 heterophilic genes (KCTD15, P-value = 0.045; SH2B1, P-value = 0.003; and TMEM18, P-value = 0.001). We also identified a lncRNA SNP (rs4358154) as a key node within the SEN using multiple network measures.

Conclusion

This study presents an analytical framework to characterize the global landscape of genetic interactions from genome-wide arrays and also to discover nodes of potential biological significance within the identified network.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13040-015-0077-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Dyadicity, Heterophilicity, Statistical epistasis networks, Epistasis, Gene-gene interaction

Background

By 2030, the obesity epidemic has the potential to affect 1.2 billion people worldwide [1]. Within the United States, a third of the adult population is categorized to be obese; this creates an estimated economic burden of $147 billion each year [2, 3]. Moreover, obesity has also been attributed to be a risk factor for conditions such as cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, cancer and premature death [4]. Therefore, this issue has drawn the focus of many public health efforts in the U.S. These efforts have been especially important for combatting rising levels of childhood obesity [2].

In addition to the influence of environmental and lifestyle factors, obesity also has a strong genetic component. It has been shown to have heritability estimates ranging between 40 and 70 % [5, 6]. However, the genetic loci that have been found to be associated with Body Mass Index (BMI) so far, can explain only a portion of its variation [7]. Epistasis or gene-gene interactions are a possible contributing factor to this ‘missing heritability’ [8, 9].

Previously, genetic variants within FTO have been identified to exhibit the strongest association with obesity in humans [3, 10–12]. However, recent studies have found that these FTO variants are in fact associated with the expression levels of a nearby gene, IRX3 [13]. Such findings have reemphasized the importance of gene-gene interactions in obesity. We aim to extend this work by studying interactions between twelve candidate obesity genes that have been consistently identified by multiple genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [7, 14–16]. Variants on these genes represent some of the strongest independent genetic associations that have been identified for BMI and account for ~1 % of the variance observed in BMI [17].

We employed previously established network science methodologies to construct a genetic interaction network and characterize epistatic interactions within this network [18, 19]. The use of networks provides an intuitive framework for studying and visualizing complex relationships between large numbers of biological entities [20]. A network is usually represented as a collection of vertices or nodes that are connected in pairs by edges. In addition to studying the properties of the nodes within this network, we also analyzed the distribution of certain node properties in relation to the underlying network structure. Park et al. have proposed the network metrics of dyadicity and heterophilicity in order to identify if interactions tend to occur more between nodes with similar characteristics [21]. We utilized these metrics in conjunction with a statistical epistasis network (SEN) to characterize gene-gene interactions associated with BMI within the Framingham Heart Study cohort.

Methods

Study cohort

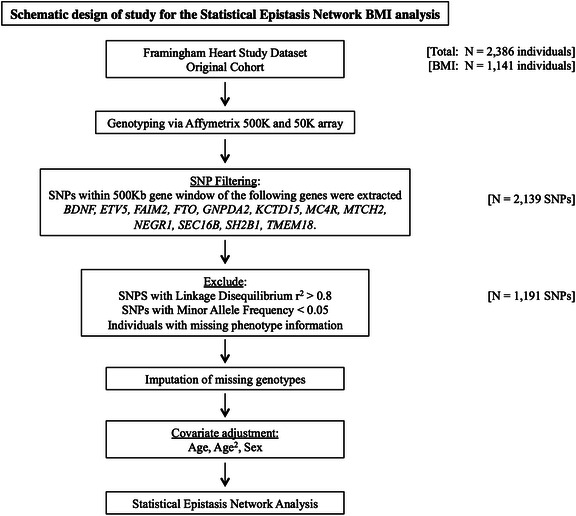

The overall study design is illustrated in Fig. 1. We combined genotypic and phenotypic information for an initial population of 2386 individuals (1133 males, 1253 females) belonging to the original cohort of the NHLBI Framingham Heart Study. This study began in 1948 and was initially designed to identify common factors that contribute to cardiovascular disease [22].

Fig. 1.

Schematic overview of analysis of Statistical Epistasis Network analysis of SNP-SNP interactions associated with BMI in the Framingham Heart Study data

Phenotype information

The original cohort included participants between the ages of 29 to 61 years, who returned every two years for a physical examination and lifestyle interviews. Phenotype information was used from the first physical exam performed. Weight was measured to the nearest pound. Height was measured to the nearest inch.

Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated according to the following formula [4]:

Individuals were categorized into obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2) and non-obese (BMI <30 kg/m2). Age and sex were obtained from the exam questionnaires.

Genotype information

We focused our analysis on SNPs belonging to the following twelve genes – BDNF, ETV5, FAIM2, FTO, GNPDA2, KCTD15, MC4R, MTCH2, NEGR1, SEC16B, SH2B1, and TMEM18 [7, 14–16]. SNPs belonging to these genes were extracted from genotype files using the PLINK --extract and --range commands [23]. SNPs were considered to fall in a gene if they were within a 500Kb window around the gene. Chromosomal locations used for defining each genomic region are listed in Additional file 1: Table S1. This was done to ensure the inclusion of potential regulatory genetic variants in the region as well.

Study participants were genotyped using the Affymetrix 500 K mapping array and the Affymetrix 50 K supplemental array. SNPs with a minor allele frequency < 0.05 were excluded. SNPs were further tested for linkage disequilibrium (LD) – a SNP was removed from each pair of SNPs that showed an LD (r2) value > 0.8. Additionally, missing genotypes were imputed using the most frequent genotype for a given marker across all individuals. This resulted in a final dataset of 1191 SNPs for 1141 individuals.

Statistical epistasis network construction

We utilized a previously developed informatics framework, Statistical Epistasis Networks (SEN), that is able to characterize the global structure of interactions between genetic variants from GWA studies [18]. The SEN method only considers purely epistatic interactions, i.e., it measures the effect of the interaction outside of the individual main effects of the interacting SNPs. This is in contrast to the traditional linear regression method of studying interactions, which is unable to disentangle main effects and purely epistatic interactions.

Dichotomized BMI values were adjusted for age, age2 and sex using a generalized linear model. Individuals with deviance residual BMI values > 0 were classified as ‘cases’; otherwise they were ‘controls’. This classification was used as the phenotype outcome in the network analysis. Additionally, there was a 100 % concordance in classification of individuals before and after covariate adjustment.

As an initial step, all pairwise epistatic interactions between SNPs were evaluated using ‘information gain’ – a metric used in Information Theory.

Before explaining information gain, we first introduce the concept of entropy, which is a measure of the uncertainty of a random variable [24, 25]. It can be explained as the average amount of information required to describe a random variable. Hence, entropy is at its maximum when all possible outcomes of a process can occur with equal probability; as predictability of an outcome increases entropy decreases.

For a discrete variable X with alphabet X and probability mass function p(x), the entropy H(X) is calculated as follows [24–26]:

Furthermore, the dependency between two random variables can be understood using mutual information [24, 26]. In genetic association studies, mutual information is useful for quantifying how much of a phenotype can be explained by genetic variants. For a SNP A and phenotype C, mutual information is calculated as follows:

where H(C) is the measure of the entropy or the uncertainty of C, and H(C|A) is the measure of conditional entropy of C given the knowledge of SNP A. Hence, mutual information describes the reduction in the uncertainty of the phenotype C due to the knowledge of genotype A. Intuitively, mutual information can be used as a measure of the independent or main effect of SNP A on phenotype C.

The concept of mutual information can also be used to study the interaction effect between a pair of SNPs A and B. It explains how much of the phenotype C can be understood when both genotypes are combined.

Thus, by subtracting the individual associations of SNPS A and B on C – I(A;C) and I(B;C) – from the total association of both SNPs, I(A,B;C), we can calculate the information gain or the gain in mutual information using the formula below [27]:

The information gain metric serves as a measure of the epistatic interaction, or synergy, between the two SNPs on explaining the phenotypic outcome C.

Within the SEN, each vertex or node corresponds to a certain SNP. The edge or connection between two nodes represents the interaction between the two SNPs. The weight of a node, or the strength of the main effect of that SNP, is represented as the size of the node. Larger node sizes correspond to stronger main effects. Lastly, the weight of an edge represents the strength of the epistatic interaction between two SNPs. Thicker edges correspond to stronger interactions [18].

The SEN was built using pairwise interactions that are stronger than a theoretically derived threshold. By gradually adjusting the edge-weight threshold, a series of networks were constructed. By inspecting the network topology, we identified the most significant threshold that resulted in a network that was the most different from what was expected by chance. In this study, we used a percolation threshold, i.e., the first time more than half the nodes of the network were connected in the largest connected component. It can be thought of as an inflection point such that after this threshold the connectivity of the network changes rapidly [25].

We also generated 1000 permuted datasets by randomly shuffling the phenotype status to reflect the null hypothesis that there is no association between the genotypes and the phenotype. For each permuted dataset, a series of networks were constructed with the same thresholds used to build the real-data networks. These permuted-data networks were used to build a null distribution to assess the statistical significance of various properties of the real-data network.

Network analysis

Dyadicity and heterophilicity are two normalized network metrics that are used to measure the correlation between node properties and the underlying network structure. Park and Barabási proposed these measures as part of an approach to assess whether vertices with similar properties tend to be connected with each other in a network [21].

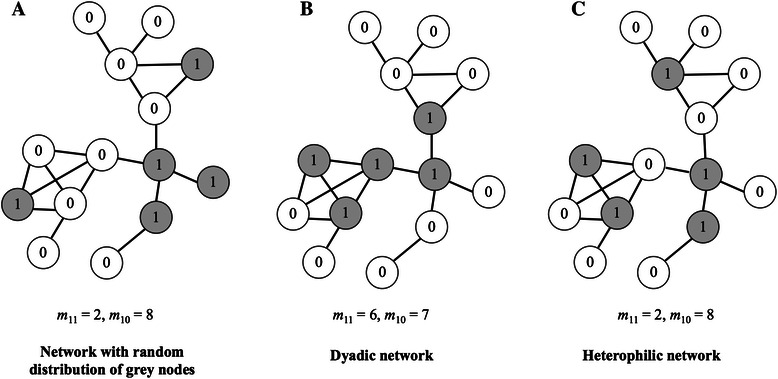

We first explored whether interactions tend to occur more between SNPs from different genes or from the same gene. In the context of this SEN, a node can be characterized by a property that takes the value of 0 or 1 (Fig. 2) [28]. In our analysis, this signifies that a certain SNP belongs to a certain gene (1) or not (0). There are three possible types of dyads, i.e., an edge and its two nodes – i) an edge and two vertices that both have the value 1, ii) an edge and two vertices with values 1 and 0, and iii) an edge and two vertices with the value 0 [21, 28]. The expected number of (1-1) and (1-0) dyads in the network are denoted as and respectively [21, 28]. Thus dyadicity (D) and heterophilicity (H) are calculated as follows:

Fig. 2.

Examples of dyadic and heterophilic distributions of node properties in a network. Nodes can be classified as either 0 or 1 (white or grey respectively). a shows a network on which 5 grey nodes are distributed randomly. b For a certain number of nodes, if edges occur more between similar nodes (i.e., 1–1 edges) than expected at random, the network is dyadic. c If edges occur more between dissimilar nodes (i.e., 1–0 edges) than at random, then the network is heterophilic

where m11 and m10 are the observed number of dyads in the network [21, 28]. This ensures that the measures of D and H are normalized and account for any variability due to the differences in the number of nodes assigned with the values of 0 or 1. A statistically significant deviation of D and H from 1 symbolizes a non-random distribution of the property in the network [21, 28]. Hence, a value of D > 1 signifies a dyadic network; a network where nodes with similar properties tend to connect with each more than expected (Fig. 2b). Similarly, a value of H > 1 signifies a heterophilic network (Fig. 2c). In such a network, nodes with a certain property tend to be more connected with nodes without that property, than expected at random.

In our analyses, we used these two metrics D and H, to assess whether interactions tend to occur more between SNPs from different genes or from the same gene. Statistical significance of the observed values of D and H was assessed using permutation testing as well. A 1000-fold permutation test was performed where the network structure and the total number of nodes with the value 1 were fixed. Next, the node value assignments of 0 and 1 were reassigned randomly, and D and H values were calculated. These values were used to build the permutation distribution used to assess the statistical significance of the D and H values of our real-data network.

In addition to characterizing the global network, a few other measures of node properties were also utilized to identify key nodes within the SEN, such as – degree, betweenness centrality and closeness centrality. These measures highlight the fact that not all nodes within a network are considered to be of equal importance. The degree of a node refers to the number of edges connecting to it [29]. Nodes with a high degree are often referred to as ‘hubs’ [30]. Betweenness centrality is a measure of the number of shortest paths that go through a node. Nodes exhibiting high betweenness centrality are often viewed as ‘bottlenecks’ of information flow, since they connect two disparate portions of a network [30]. Closeness centrality is calculated as the reciprocal of the sum of the total distance to all other vertices in the network [31].

Integrated Multi-Species Prediction (IMP) web server

We also used the Integrated Multi-Species Prediction (IMP) web server to query genes represented by the SNPs within the most significant pairwise interaction [32]. IMP serves as a repository that combines biological evidence from multiple sources such as gene expression studies, IntAct, MINT, MIPS, and BioGRID databases. The software then mines such empirical data to provide a probability score that two genes are involved in a functional and biological relationship.

Results

Gene categorization

SNPs included in the study were chosen from twelve candidate obesity genes. Additional file 1: Table S1 shows the number of SNPs that were included from each gene. The known biological roles of each of these genes are also described in detail (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Statistical epistasis network

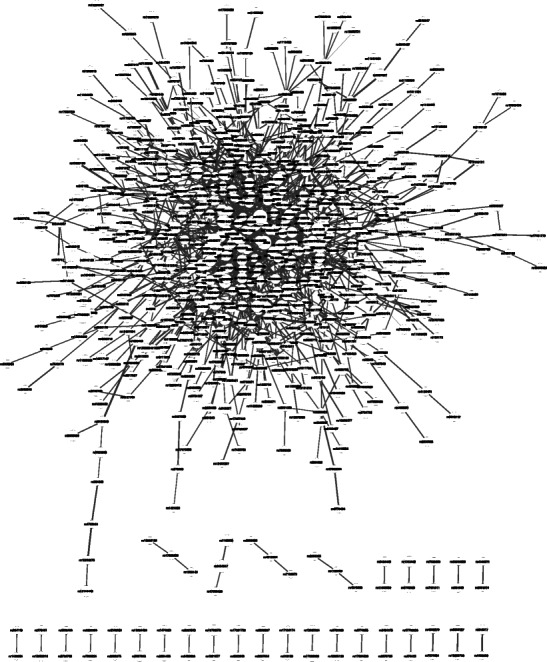

At a percolation threshold of 0.023379, we identified a highly connected SEN comprised of 771 SNPs as nodes and 1241 edges (Fig. 3). The number of nodes included in our SEN was statistically significant with a P-value = 0.036. The largest connected component consisted of 709 SNPs and has a statistically significant size compared to all 1000 permuted-data networks at the same threshold with a P-value = 0.046.

Fig. 3.

Statistical Epistasis Network of SNPs from 12 candidate obesity genes associated with BMI. Each node represents a SNP, and each edge connecting two nodes represents an interaction. Shown here is the SEN at a percolation threshold of 0.023379, with 771 nodes and 1241 edges. The largest connected component is comprised of 709 nodes. This network was rendered using Cytoscape

Measures of main effect and interaction strength

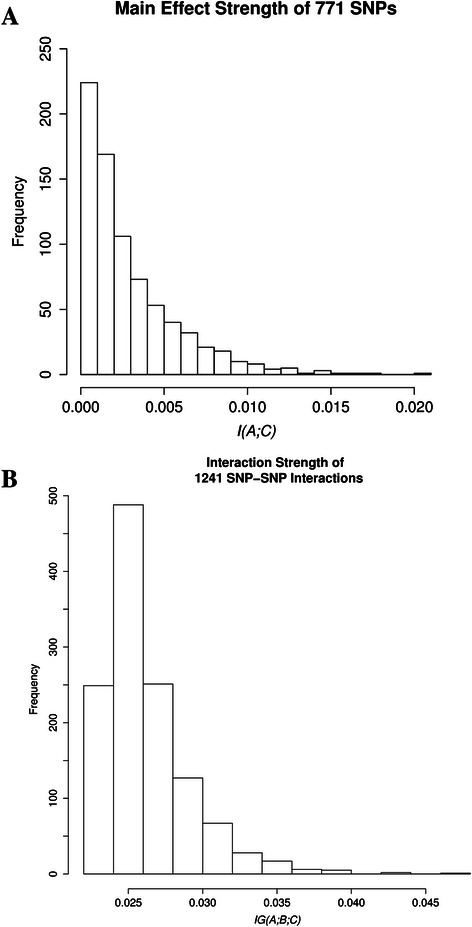

Figure 4a shows the frequency distribution of the main effect strengths or mutual information values of all individual SNPs associated with BMI, within the network at the percolation threshold. Within this network, we identified 58 SNPs with a statistically significant main effect (P-value < 0.05) (Additional file 2: Table S2). The 5 strongest main effects are shown in Table 1.

Fig. 4.

Frequency distributions of mutual information and information gain in the Statistical Epistasis Network. Shown here are the distributions of a the main effect strengths of 771 SNPs and b the interaction strengths of 1241 SNP-SNP interactions associated with BMI within the network

Table 1.

Mutual information values for five SNPs with the strongest main effects associated with BMI within the Statistical Epistasis Network at the percolation threshold

| SNP | Gene | Mutual Information | Permuted P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs17066891 | MC4R | 0.020138781 | <0.001 |

| rs9940128 | FTO | 0.01695201 | 0.001 |

| rs1866510 | GNPDA2 | 0.017895503 | 0.002 |

| rs9949577 | MC4R | 0.014867522 | 0.002 |

| rs12696555 | ETV5 | 0.013757477 | 0.004 |

The corresponding gene for each SNP is also shown. Main effect strengths are measured using mutual information [I(A;C)]. P-values were calculated from a 1000 permutations

The frequency distribution of interaction strengths of all 1241 pairwise SNP-SNP interactions associated with BMI, within the network at the percolation threshold is shown in Fig. 4b. All the interactions were highly significant with a P-value < 0.001 (Additional file 3: Table S3). The five strongest interactions are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Shown are the five SNP-SNP interactions with the highest information gain values for BMI within the Statistical Epistasis Network at the percolation threshold

| Interaction | SNP1 | Gene1 | SNP2 | Gene2 | Information Gain | Permuted P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs2867133,rs9878325 | rs2867133 | TMEM18 | rs9878325 | ETV5 | 0.0473789 | <0.001 |

| rs7110708,rs8105874 | rs7110708 | BDNF | rs8105874 | KCTD15 | 0.043324175 | <0.001 |

| rs17360705,rs1673518 | rs17360705 | SEC16B | rs1673518 | MC4R | 0.042418682 | <0.001 |

| rs10798574,rs2245826 | rs10798574 | SEC16B | rs2245826 | BDNF | 0.03917757 | <0.001 |

| rs8179316,rs1316803 | rs8179316 | NEGR1 | rs1316803 | TMEM18 | 0.038534544 | <0.001 |

The corresponding gene for each SNP is also shown. SNP-SNP interactions are measured using information gain [IG(A;B;C)]. P-values were calculated from a 1000 permutations

Dyadicity and heterophilicity of gene categories

Table 3 shows the dyadicity and heterophilicity values for each of the twelve candidate obesity genes. TMEM18 was the only gene that showed significant dyadicity (P-value = 0.04). Three genes showed significant heterophilicity: TMEM18 (P-value <0.001), SH2B1 (P-value = 0.001) and KCTD15 (P-value = 0.038). Additional file 4: Figure S1; Additional file 5: Figure S2; Additional file 6: Figure S3 and Additional file 7: Figure S4 show the null distributions used to assess the statistical significance of the dyadicity and heterophilicity values of TMEM18, SH2B1, and KCTD15 from 1000 permuted networks.

Table 3.

Results from dyadicity and heterophilicity analysis of the statistical epistasis network. Shown are the dyadicity and heterophilicity values for each of the twelve candidate obesity genes

| Gene | n 1 | m 11 expected | m 10 expected | m 11 observed | m 10 observed | D | H | P-valueD | P-valueH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTO | 324 | 28.399 | 319.157 | 21 | 301 | 0.739 | 0.943 | 0.85 | 0.727 |

| MC4R | 187 | 9.439 | 198.109 | 16 | 219 | 1.695 | 1.105 | 0.074 | 0.248 |

| KCTD15 | 178 | 8.550 | 189.444 | 5 | 243 | 0.585 | 1.283 | 0.855 | 0.045 |

| TMEM18 | 222 | 13.314 | 230.971 | 23 | 334 | 1.728 | 1.446 | 0.047 | 0.001 |

| NEGR1 | 295 | 23.535 | 295.234 | 12 | 249 | 0.510 | 0.843 | 0.978 | 0.94 |

| SH2B1 | 32 | 0.269 | 36.593 | 1 | 87 | 3.715 | 2.378 | 0.232 | 0.003 |

| FAIM2 | 106 | 3.020 | 116.957 | 1 | 103 | 0.331 | 0.881 | 0.91 | 0.699 |

| SEC16B | 165 | 7.343 | 176.772 | 2 | 197 | 0.272 | 1.114 | 0.979 | 0.218 |

| ETV5 | 168 | 7.613 | 179.713 | 3 | 173 | 0.394 | 0.963 | 0.952 | 0.596 |

| BDNF | 167 | 7.523 | 178.734 | 1 | 167 | 0.133 | 0.934 | 0.997 | 0.643 |

| MTCH2 | 109 | 3.195 | 120.090 | 1 | 110 | 0.313 | 0.916 | 0.908 | 0.664 |

| GNPDA2 | 186 | 9.338 | 197.151 | 1 | 125 | 0.107 | 0.634 | 1 | 0.997 |

P-values were calculated from 1000 permutations. P-values <0.05 are highlighted in bold

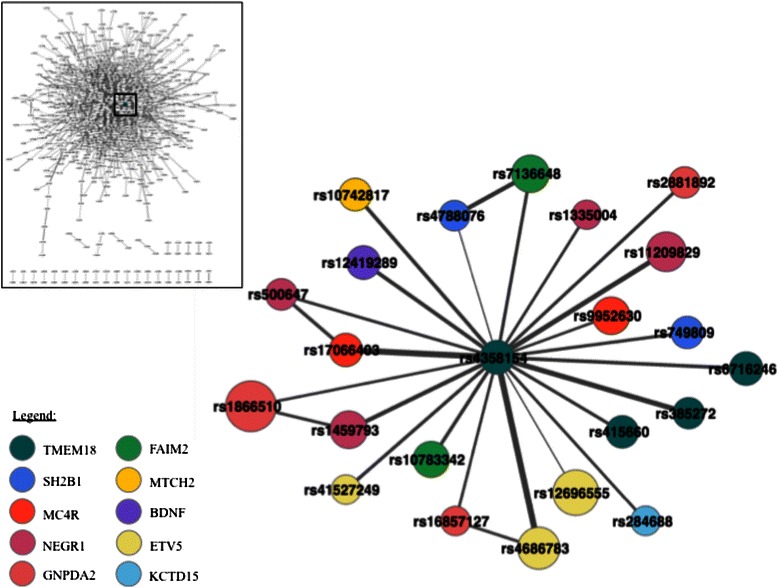

Measures of node properties – degree, betweenness centrality and closeness centrality

Values for degree, betweenness centrality and closeness centrality were calculated for all SNPs within the largest connected component of the network (Additional file 8: Table S4). The corresponding frequency distribution of these three node properties is presented in Additional file 9: Figure S5; Additional file 10: Figure S6 and Additional file 11: Figure S7. Table 4 shows the SNPs with the 5 highest values for each of these measures. rs4358154 in TMEM18 had the highest value for all three measures.

Table 4.

Shown here are the five SNPs with the highest degree, betweenness centrality and closeness centrality scores respectively, amongst all SNPs in the largest connected component of the Statistical Epistasis Network

| SNP | Gene | Degree |

|---|---|---|

| rs4358154 | TMEM18 | 22 |

| rs285690 | KCTD15 | 18 |

| rs3817334 | MTCH2 | 17 |

| rs529579 | KCTD15 | 17 |

| rs4650977 | SEC16B | 17 |

| SNP | Gene | Betweenness Centrality |

| rs4358154 | TMEM18 | 0.08366177 |

| rs4650977 | SEC16B | 0.06191228 |

| rs2278260 | KCTD15 | 0.05311856 |

| rs529579 | KCTD15 | 0.05173649 |

| rs10742817 | MTCH2 | 0.05150078 |

| SNP | Gene | Closeness Centrality |

| rs4358154 | TMEM18 | 0.29611041 |

| rs3817334 | MTCH2 | 0.29598662 |

| rs2278260 | KCTD15 | 0.29377593 |

| rs17066403 | MC4R | 0.29304636 |

| rs529579 | KCTD15 | 0.29256198 |

The corresponding gene for each SNP is also shown

Discussion

The need for embracing the complexity of data from genome-wide genotyping arrays, also presents a bioinformatics challenge. Trying to study interactions between thousands of genetic variants can be computationally demanding. However, this is important for truly elucidating the disease mechanisms of complex disorders. The use of network science and information theory provides an intuitive framework for representing the inter-connectedness between biological entities and assessing the global structure of these interactions. It also enables researchers to identify key network nodes by studying the interplay between global network properties and node properties. Studying gene-gene interactions has been especially important in the context of obesity, as shown in recent studies.

In this study, we constructed an SEN of SNPs from twelve candidate obesity genes. SNPs belonging to these genes were filtered from the Framingham Heart Study dataset. Initially, all pairwise SNP-SNP interactions associated with BMI were calculated, using the ‘information gain’ measure. Next, SNP-SNP interactions exceeding a certain threshold were used to construct the network. The corresponding gene for each SNP was also overlaid onto this network. This was used in combination with the network measures of dyadicity and heterophilicity to investigate the nature of interactions within the SEN. We aimed to understand if interactions tend to occur more between different genes or within the same gene.

We identified a highly connected SEN that had a largest connected component consisting of nearly 90 % of the total number of SNPS (709 out of 771 SNPs) in the network. This reflects the complex interconnectedness that may be playing into the disease mechanism of obesity. rs17066891 in MC4R was identified as having the strongest main effect within this network (Table 1). To the best of our knowledge, this SNP has not been implicated in obesity previously. The SNP rs9940128 in FTO was identified as having the second strongest main effect in the network (Table 1). This SNP has been previously identified to be associated with BMI with a genome-wide significance, in adolescents and young adults [33].

The information gain measure is mathematically designed for identifying synergistic interactions that help explain a phenotype, beyond what is learned about it through the independent effects of SNPs. The SNP-SNP interaction with most information gained about BMI is between rs2867133 in TMEM18 and rs9878325 in ETV5 (Table 2). TMEM18 has been found to be widely expressed in the brain, including the hypothalamus – the region responsible for controlling the feeling of satiety [34]. This finding corresponds with the previously established role of the central nervous system (CNS) in obesity [35]. ETV5 encodes for a transcription factor belonging to the ETS family [36].

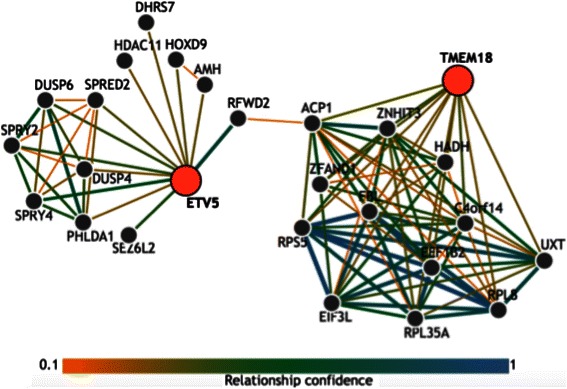

Using IMP, we identified a functional relationship connecting TMEM18 and ETV5 (Fig. 5) [32]. ETV5 is known to physically interact with the E3 ubiquitin protein ligase encoded by RFWD2 [32]. This ubiquitin ligase interacts with ACP1, a phosphatase [32]. There was also some support for the interaction between ACP1 and TMEM18 in the network. TMEM18 is known to have conserved phosphorylation sites [36]. Hence, the interaction between ETV5 and TMEM18 could be highlighting a regulatory relationship. ACP1 may be involved in the post-translational modification of TMEM18. Moreover, the possible degradation of ACP1 due to ubiquitination could add an additional layer of regulation.

Fig. 5.

Functional relationship network generated from Integrated Multi-Species Prediction (IMP) reflecting the BMI associated SNP-SNP interaction between rs2867133 in TMEM18 and rs9878325 in ETV5. SNPs were mapped to their respective genes and used to query IMP. Nodes in the network represent genes. Orange nodes are the genes that were queried. Edges between nodes represent a functional relationship between two genes. The color of the edge signifies the strength of the relationship confidence

We also performed dyadicity and heterophilicity analyses to characterize the gene-gene interactions within the SEN. We identified three genes with significant heterophilicity (SH2B1, KCTD15 and TMEM18), and one gene with significant dyadicity (TMEM18). Heterophilic genes were involved in more SNP-SNP interactions with other genes than expected at random. SH2B1 encodes for a cytoplasmic adaptor protein and has been implicated in leptin signaling [37]. The significant heterophilicity of this gene may be due to the fact that adaptor proteins contribute to the cross-talk between various signaling cascades by bringing together larger protein complexes [38]. Moreover, the obesity observed in Sh2b1-null mice was reversed by the targeted expression of Sh2b1 in neurons [37]. This was important for highlighting the role of the CNS in the development of obesity, since SH2B1 is expressed both in the CNS and peripheral tissues [35, 37]. The other two heterophilic genes TMEM18 and KCTD15 have unknown functions but are known to be highly expressed in the hypothalamus and brain [35]. Ultimately, these genes reemphasize the brain’s role in the development of obesity. Their significant heterophilicity may be a reflection of their biologically central role in regulating the actions of various cells and organs from within the brain.

TMEM18 also showed marginally significant dyadicity (P-value = 0.04). Dyadic genes were part of more intra-genic interactions than expected at random. We identified 23 intra-genic interactions between SNPs in TMEM18, to be associated with BMI within the SEN (Additional file 3: Table S3). Although the biological effect of such interactions within TMEM18 is unknown, these interactions may influence the gene’s function and obesity through regulatory and epigenetic mechanisms.

We also utilized network measures such as degree, betweenness centrality and closeness centrality to identify nodes within the SEN that may be of potential biological relevance. In the case of biological networks, certain nodes may play a more important role in the proper functioning of a cell [39] or may serve as better targets for intervention [40]. Researchers have found that hubs within a protein interaction network are encoded by essential genes in model organisms [39]. Moreover, in similar networks, proteins that are also bottlenecks, have been found to be of high biological significance and are often encoded by essential genes as well [41]. The closeness centrality measure has been utilized for identifying central nodes in various types of networks such as metabolic networks [42].

In our analyses, we identified a SNP (rs4358154) in TMEM18 that had the highest score for all three measures described above (Table 3, Fig. 6). This not only highlights the potentially significant role of this SNP in the context of obesity, but may also represent the highly significant heterophilicity of TMEM18 within the SEN. The SNP is of unknown function, but it is known to be located on LINC01115, a long intergenic non-protein coding RNA (lncRNA), located approximately 102 kb downstream of TMEM18 [43]. Unfortunately, not much is known regarding the function of LINC01115 as well. However, using the NONCODEv4 database, we found that this lncRNA shows most expression within the brain [44]. The regulatory role of lncRNAs has been investigated in various contexts including adipogenesis. Researchers have identified lncRNAs as a potential additional layer of regulation involved in the development of mature adipocytes or fat cells [45].

Fig. 6.

Focused view on the node (rs4358154 in TMEM18) showing the highest degree, betweenness centrality and closeness centrality within the Statistical Epistasis Network. Shown are all the direct neighboring nodes of rs4358154. Nodes are color coded based on their gene category. Node size represents the strength of the main effect of a SNP. The thickness of an edge represents the strength of the interaction between two SNPs

Understanding the regulatory mechanisms involved in the development of fat cells is of special importance for the advancement of future anti-obesity treatments. Humans have two types of fat cells – white and brown. Accumulation of white fat cells causes obesity since they store excess energy as fat or lipid droplets [46]. However, brown fat cells that are more abundant in infants use lipids as a fuel to maintain a warm body temperature [46]. Hence, researchers are interested in exploring the role of regulators such as lncRNAs in the development of each type of fat cell and learning how such processes may be manipulated.

Conclusion

Exhaustively studying all pairwise interactions between SNPs from a genome-wide array can present a computationally challenging problem. In this study we used a network-based approach to investigate all pairwise interactions between SNPs in twelve candidate obesity genes within the Framingham Heart Study dataset. The use of this methodology enabled us to capture the landscape of interactions between genes known to be associated with BMI and to better understand which interactions are predictive of BMI. Furthermore, we were able to characterize these interactions, emphasize new roles of these genes and highlight the involvement of regulatory frameworks in the development of obesity.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institute of Health (NIH) grants: NLM R01 grants (LM010098, LM009012) and GMS P20 grant (GM104416).

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body mass index

- GWAS

Genome wide association study

- SEN

Statistical epistasis network

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- LD

Linkage disequilibrium

Additional files

Gene categorization. Shown here are the chromosomal locations (NCBI build 36) used to assign a SNP to a gene. Chromosomal location refers to the gene’s boundaries +/− a 500 kb window around it. The number of SNPs that were categorized to each of the 12 candidate obesity genes are also shown. Known biological roles of genes were found using GeneCards database (www.genecards.org, Accessed March 31, 2015) or from the literature sources cited. (XLSX 39 kb)

Mutual information values for 58 SNPs within the network at the percolation threshold. Shown here are the statistically significant mutual information values (p-value < 0.05) of 58 SNPs within the network at the percolation threshold. P-values were calculated from a 1000 permutations. (XLSX 48 kb)

Information gain values for 1241 edges within the network at the percolation threshold. Shown here are the statistically significant information gain values (p-value < 0.05) of 1241 edges within the network at the percolation threshold. P-values were calculated from a 1000 permutations. Also shown are the corresponding genes for each SNP. (XLSX 139 kb)

Null distribution of heterophilicity values of KCTD15 from 1000 permuted networks. Null distribution of heterophilicity values of KCTD15 from 1000 permuted networks. The red line indicates the observed heterophilicity value of KCTD15 within the real data network. (PDF 12 kb)

Null distribution of heterophilicity values of SH2B1 from 1000 permuted networks. Null distribution of heterophilicity values of SH2B1 from 1000 permuted networks. The red line indicates the observed heterophilicity value of SH2B1 within the real data network. (PDF 12 kb)

Null distribution of heterophilicity values of TMEM18 from 1000 permuted networks. Null distribution of heterophilicity values of TMEM18 from 1000 permuted networks. The red line indicates the observed heterophilicity value of TMEM18 within the real data network. (PDF 12 kb)

Null distribution of dyadicity values of TMEM18 from 1000 permuted networks. Null distribution of dyadicity values of TMEM18 from 1000 permuted networks. The red line indicates the observed heterophilicity value of TMEM18 within the real data network. (PDF 12 kb)

Degree, betweenness centrality and closeness centrality values of 709 SNPs within the largest component of the network at the percolation threshold. Shown here are the values for degree, betweenness centrality and closeness centrality of 709 SNPs within the largest component of the Statistical Epistasis Network at the percolation threshold. (XLSX 81 kb)

Frequency distribution of node degree values within the SEN. Frequency distribution of node degree of 709 SNPs within the giant connected component of the SEN. The green line indicates the top 5 % of node degree values. (PDF 18 kb)

Frequency distribution of node betweenness centrality values within the SEN. Frequency distribution of node betweenness centrality measures of 709 SNPs within the giant connected component of the SEN. The green line indicates the top 5 % of betweenness centrality values. (PDF 20 kb)

Frequency distribution of node closeness centrality values within the SEN. Frequency distribution of node closeness centrality measures of 709 SNPs within the giant connected component of the SEN. The green line indicates the top 5 % of closeness centrality values. (PDF 21 kb)

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

RD performed data extraction, data processing, post-hoc analyses and drafted the manuscript. TH performed network analyses. JHM and DGD conceived of the study and participated in its design. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Rishika De, Email: Rishika.De@dartmouth.edu.

Ting Hu, Email: ting.hu@mun.ca.

Jason H. Moore, Email: jhmoore@upenn.edu

Diane Gilbert-Diamond, Email: Diane.Gilbert-Diamond@dartmouth.edu.

References

- 1.Kelly T, Yang W, Chen C-S, Reynolds K, He J. Global burden of obesity in 2005 and projections to 2030. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:1431–7. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014;311:806–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scuteri A, Sanna S, Chen W, Uda M, Albai G, Strait J, et al. Genome-wide association scan shows genetic variants in the FTO gene are associated with obesity-related traits. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults--The Evidence Report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res. 1998;6(Suppl 2):51S–209S [PubMed]

- 5.Stunkard AJ, Foch TT, Hrubec Z. A twin study of human obesity. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 1986;256:51–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.1986.03380010055024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maes HH, Neale MC, Eaves LJ. Genetic and environmental factors in relative body weight and human adiposity. Behav Genet. 1997;27:325–51. doi: 10.1023/A:1025635913927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Speliotes EK, Willer CJ, Berndt SI, Monda KL, Thorleifsson G, Jackson AU, et al. Association analyses of 249,796 individuals reveal 18 new loci associated with body mass index. Nat Genet. 2010;42:937–48. doi: 10.1038/ng.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eichler EE, Flint J, Gibson G, Kong A, Leal SM, Moore JH, et al. Missing heritability and strategies for finding the underlying causes of complex disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:446–50. doi: 10.1038/nrg2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manolio TA, Collins FS, Cox NJ, Goldstein DB, Hindorff LA, Hunter DJ, et al. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature. 2009;461:747–53. doi: 10.1038/nature08494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frayling TM, Timpson NJ, Weedon MN, Zeggini E, Freathy RM, Lindgren CM, et al. A common variant in the FTO gene is associated with body mass index and predisposes to childhood and adult obesity. Science. 2007;316:889–94. doi: 10.1126/science.1141634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Church C, Moir L, McMurray F, Girard C, Banks GT, Teboul L, et al. Overexpression of Fto leads to increased food intake and results in obesity. Nat Genet. 2010;42:1086–92. doi: 10.1038/ng.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dina C, Meyre D, Gallina S, Durand E, Körner A, Jacobson P, et al. Variation in FTO contributes to childhood obesity and severe adult obesity. Nat Genet. 2007;39:724–6. doi: 10.1038/ng2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smemo S, Tena JJ, Kim K-H, Gamazon ER, Sakabe NJ, Gómez-Marín C, et al. Obesity-associated variants within FTO form long-range functional connections with IRX3. Nature. 2014;507:371. doi: 10.1038/nature13138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willer CJ, Speliotes EK, Loos RJF, Lindgren CM, Heid IM, Berndt SI, et al. UKPMC Funders Group Six new loci associated with body mass index highlight a neuronal influence on body weight regulation. Nat Genet. 2009;41:25–34. doi: 10.1038/ng.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thorleifsson G, Walters GB, Gudbjartsson DF, Steinthorsdottir V, Sulem P, Helgadottir A, et al. Genome-wide association yields new sequence variants at seven loci that associate with measures of obesity. Nat Genet. 2009;41:18–24. doi: 10.1038/ng.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loos RJF. Genetic determinants of common obesity and their value in prediction. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26:211–26. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Speliotes EK, Willer CJ, Berndt SI, Monda KL, Thorleifsson G, Jackson AU, et al. Association analyses of 249,796 individuals reveal eighteen new loci associated with body mass index. Nat Genet. 2011;42:937–48. doi: 10.1038/ng.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu T, Sinnott-Armstrong N, Kiralis JW, Andrew AS, Karagas MR, Moore JH. Characterizing genetic interactions in human disease association studies using statistical epistasis networks. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:364. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu T, Chen Y, Kiralis JW, Moore JH. ViSEN: methodology and software for visualization of statistical epistasis networks. Genet Epidemiol. 2013;37:283–5. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strogatz SH. Exploring complex networks. Nature. 2001;410:268–76. doi: 10.1038/35065725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park J, Barabási A-L. Distribution of node characteristics in complex networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:17916–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705081104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dawber TR, Meadors GF, Moore FE. Epidemiological approaches to heart disease: the Framingham Study. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1951;41:279–81. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.41.3.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MAR, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–75. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cover TM, Thomas JA. Entropy, Relative Entropy, and Mutual Information. In Elements of Information Theory. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2005:13–55 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/book/10.1002/047174882X;jsessionid=E8D9E7A4D723F69CBCB783E41B145441.f04t01

- 25.Moore J, Hu T. Epistasis Analysis Using Information Theory. In: Moore JH, Williams SM, editors. Epistasis SE - 13. Volume 1253. New York: Springer; 2015. pp. 257–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu T, Chen Y, Kiralis JW, Collins RL, Wejse C, Sirugo G, et al. An information-gain approach to detecting three-way epistatic interactions in genetic association studies. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20:630–6. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore JH, Gilbert JC, Tsai C-T, Chiang F-T, Holden T, Barney N, et al. A flexible computational framework for detecting, characterizing, and interpreting statistical patterns of epistasis in genetic studies of human disease susceptibility. J Theor Biol. 2006;241:252–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu T, Andrew AS, Karagas MR, Moore JH. The functional dyadicity and heterophilicity of gene-gene interactions in statistical epistasis networks. BioData Min 2015(in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Zhu X, Gerstein M, Snyder M. Getting connected: analysis and principles of biological networks Getting connected: analysis and principles of biological networks. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1010–24. doi: 10.1101/gad.1528707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barabási A-L, Gulbahce N, Loscalzo J. Network medicine: a network-based approach to human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:56–68. doi: 10.1038/nrg2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sabidussi G. The centrality index of a graph. Psychometrika. 1966;31:581–603. doi: 10.1007/BF02289527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong AK, Park CY, Greene CS, Bongo L, Guan Y, Troyanskaya OG. IMP: a multi-species functional genomics portal for integration, visualization and prediction of protein functions and networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Web Server issue):W484–90. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Graff M, Ngwa JS, Workalemahu T, Homuth G, Schipf S, Teumer A, et al. Genome-wide analysis of BMI in adolescents and young adults reveals additional insight into the effects of genetic loci over the life course. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22(17):3597–607. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Almén MS, Jacobsson J, Shaik JH, Olszewski PK, Cedernaes J, Alsiö J, et al. The obesity gene, TMEM18, is of ancient origin, found in majority of neuronal cells in all major brain regions and associated with obesity in severely obese children. BMC Med Genet. 2010;11:58. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-11-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Willer CJ, Speliotes EK, Loos RJF, Li S, Lindgren CM, Heid IM, et al. Six new loci associated with body mass index highlight a neuronal influence on body weight regulation. Nat Genet. 2009;41:25–34. doi: 10.1038/ng.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Speakman JR. Functional analysis of seven genes linked to body mass index and adiposity by genome-wide association studies: a review. Hum Hered. 2013;75:57–79. doi: 10.1159/000353585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ren D, Zhou Y, Morris D, Li M, Li Z, Rui L. Neuronal SH2B1 is essential for controlling energy and glucose homeostasis. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:397–406. doi: 10.1172/JCI29417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flynn DC. Adaptor proteins. Oncogene. 2001;20:6270–2. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jeong H, Mason SP, Barabási a L, Oltvai ZN. Lethality and centrality in protein networks. Nature. 2001;411:41–2. doi: 10.1038/35075138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Penrod NM, Moore JH. Key genes for modulating information flow play a temporal role as breast tumor coexpression networks are dynamically rewired by letrozole. BMC Med Genomics. 2013;6(Suppl 2):S2. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-6-S2-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu H, Kim PM, Sprecher E, Trifonov V, Gerstein M. The importance of bottlenecks in protein networks: correlation with gene essentiality and expression dynamics. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007;3:e59. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ma HW, Zeng AP. The connectivity structure, giant strong component and centrality of metabolic networks. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1423–30. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sherry ST, Ward MH, Kholodov M, Baker J, Phan L, Smigielski EM, et al. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:308–11. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xie C, Yuan J, Li H, Li M, Zhao G, Bu D, et al. NONCODEv4: exploring the world of long non-coding RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D98–103. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun L, Goff L a, Trapnell C, Alexander R, Lo KA, Hacisuleyman E, et al. Long noncoding RNAs regulate adipogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:3387–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222643110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cypess AM, Lehman S, Williams G, Tal I, Rodman D, Goldfine AB, et al. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1509–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]