Abstract

Aim

The aim of this study was to look at the influence of metformin intake and duration, on urinary bladder cancer (UBC) risk, with sulfonylurea (SU) only users as control using a new user design (inception cohort).

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) including all patients with at least one prescription of oral anti‐diabetic drugs (ADD) and/or insulin. The risk of UBC in different groups of ADD users (metformin alone (one), metformin in combination (two) with other ADD medication (glinides, glitazones, DPP‐4‐inhibitors, SUs, insulin or more than one combination), all metformin users (1 + 2) was compared with SU only users using Cox proportional hazards models. The estimates were adjusted for age, gender, smoking status, BMI and diabetes duration.

Results

The inception cohort included 165 398 participants of whom 132 960 were metformin users and 32 438 were SU only users. During a mean follow‐up time of more than 5 years 693 patients developed UBC, 124 of the control group and 461 of the all metformin users. There was no association between metformin use and UBC risk (HR = 1.12, 95% CI 0.90, 1.40) compared with SU only users, even after adjustment for diabetes duration (HR = 1.13, 95% CI 0.90, 1.40). We found a pattern of decreasing risk of UBC with increasing duration of metformin intake, which was statistically not significant.

Conclusion

Metformin has no influence on the risk of UBC compared with SU in type 2 diabetes patients using a new user design.

Keywords: bladder cancer, metformin, type 2 diabetes mellitus

What is Already Known About this Subject

Epidemiological studies suggest a protective effect of metformin on cancer.

A meta‐analysis of clinical trials could not confirm this protective effect.

Metformin inhibits the growth of bladder cancer cells in vitro and in vivo and may diminish recurrence and progression of non‐invasive bladder cancer and recurrence and mortality after radical cystectomy.

What this Study Adds

Metformin has no protective effect on the risk of bladder cancer.

This study confirms the importance to use data from incident users in pharmacological epidemiology in order to eliminate time related bias and to obtain reliable results.

Introduction

In 2014, in the United Kingdom (UK) 5.4% of the population was a diabetes patient while worldwide, diabetes mellitus affected 387 million adults (aged 20–79 years) causing nearly five million deaths 1. In 2012, more than 400 000 bladder cancer (UBC) cases occurred worldwide, making it the seventh most common type of cancer 2. Although most cohort and case–control studies demonstrated an increased risk of UBC due to type 2 diabetes compared with non‐diabetic controls with a relative risk (RR) ranging from 1.11 (95% CI 1.00, 1.23) to 1.32 (95% CI 1.18, 1.49) adjusted for smokers 3, 4, 5, neither the risk of UBC nor the mortality from UBC was increased in patients with type 1 and patients with type 2 diabetes in the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.77 (95% CI 0.57, 1.05) and 1.04 (95% CI 0.96, 1.14) for type 1 and 2 diabetes, respectively 6. The influence of different anti‐diabetic drugs (ADD), especially metformin, on the risk of UBC is still unclear. The reduction of circulating levels of insulin and insulin‐like growth factor 1 (IGF‐1) by metformin might be associated with anticancer action. Insulin/IGF‐1 are involved not only in regulation of glucose uptake but also in carcinogenesis through up‐regulation of the insulin/IGF receptor signalling pathway. Furthermore, metformin is thought to inhibit the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, which plays a pivotal role in metabolism, growth and proliferation of cancer cells 7 Currently metformin, as an anti‐cancer drug, is under investigation in 199 clinical trials 8. Metformin, as well as sulfonylurea (SU), are used as a first line treatment for type 2 diabetes and both are used in monotherapy in early stage of type 2 diabetes 9, 10. Epidemiological evidence suggests that metformin reduces the risk of cancer 11, 12, 13, 14, including bladder cancer 15 and cancer‐related mortality 16, 17. Metformin inhibits the growth of bladder cancer cells in vitro and in vivo 18, 19 and may diminish recurrence and progression of non‐invasive bladder cancer and recurrence and mortality after radical cystectomy 20, 21. However, epidemiological studies were likely subject to confounding by indication and were not designed to differentiate between the effect of the drug from that of the underlying disease. A recent meta‐analysis of randomized clinical trials (RCT) evaluating cancer outcome in patients using metformin did not confirm the hypothesis that metformin lowers cancer risk 22. RCTs are less subject to time‐related bias than observational studies. Time‐related biases 23 include immortal time bias, a bias introduced with time‐fixed cohort analyses that misclassify unexposed time as exposed as is the case in the study from Bowker et al. 17 time‐window bias, a bias introduced because of differential exposure opportunity time windows between subjects as is the case in the study from Ngwana et al. 14 and time‐lag bias, a bias introduced by comparing treatments given at different stages of the disease as in the study from Libby et al. 13. Analyzing patients according to time since the start of the medication under surveillance using a new user design 24 or inception cohort, prevents time‐related bias and brings the results to fall in line with the results from clinical trials 25.

We examined the influence of metformin intake, including duration, on UBC risk, with SU only users as control using a new user design (inception cohort).

Methods

Data sources

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) (January 1987−October 2013). The CPRD comprises prospectively collected computerized medical records of over 10 million patients under the care of more than 600 general practitioners (GPs) in the United Kingdom (UK). The Read classification 26 is used to enter medical diagnoses and procedures, and prescriptions are recorded based on the UK Prescription Pricing Authority Dictionary 27. The recorded information on diagnoses and drug use has been validated and proven to be of high quality 28, 29.

Study population

All patients with at least one prescription of ADDs (oral non‐insulin anti‐diabetic drugs (NIAD) and/or insulin) and aged 18 years or older during the period of CPRD data collection were included. The date of the first ADD prescription was defined as the index date (baseline or t 0) of the start cohort. From this start cohort, all subjects with missing data for smoking status, a history of any cancer prior to the index date, except non‐melanoma skin cancer, a diagnosis of gestational diabetes or secondary diabetes ever during follow‐up were excluded. Furthermore, all ADD users with diagnoses of both type 1 and 2 diabetes and all ADD users with diagnoses of type 1 diabetes were excluded as were all ADD users with only insulin use at baseline and younger than 30 years. The full cohort was further restricted to all patients with at least 1 year without exposure to ADDs before the start of treatment (t 0), (1 year of non‐use or washout prior to t 0) to create the inception cohort. All study participants were followed up from the index date to either the end of data collection, the date of transfer of the patient out of the practice area, or the patient's death.

Exposure

Patients with type 2 diabetes were all patients with a formal diagnosis of type 2 diabetes or using an oral ADD at index date. The total period of follow‐up for each patient was divided into fixed time periods of 90 days. Age was determined at the start of each interval. Gender, smoking status and BMI were determined at baseline. Diabetes duration was assessed retrospectively by estimating the time since the date of the first ADD prescription (the index date, t 0). Diabetes control was assessed in a time‐dependent manner using the most recent HbA1c record before the start of each time interval in the previous year.

Current exposure to all ADDs was assessed at the start of each interval in a time‐dependent manner. Current use was defined as a prescription at the start date or in the 90 days before. Current use was further stratified by type of ADD. Additional to insulin, the following classes of ADDs were defined: biguanides (metformin), sulfonylureas (SUs) (glibenclamide, gliclazide, glimepiride, glipizide, gliquidon), glinides (repaglinide), glitazones or thiazolidinesdiones (pioglitazone, rosiglitazone), dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitors (DPP‐4‐inhibitors) (saxagliptin, sitagliptin, vildagliptin). All NIADs not belonging to these specific categories were combined in a separate category (other ADD users). This category contained the following groups: glinides only, glitazones only, DPP‐4‐inhibitors only, insulin only, SUs combined (not‐metformin) and others including incretinemimetica (exenatide, liraglutide). When there was no prescription in the 90 days before the start of an interval, the interval was classified as past use.

Controls were those patients who had used SUs alone.

Outcomes

Patients were followed up for the occurrence of a first medical record for bladder cancer, as defined by Read codes in CPRD.

Potential confounders

The major covariates of interest included age, gender, smoking status and BMI. Smoking status was characterized at baseline as current, former or non‐smoker. Age was assessed in a time‐dependent manner. Additional covariates were retinopathy and neuropathy as a measure for diabetes complications, HbA1c as a measure for diabetes control and diabetes duration.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted using Cox proportional hazards models. Risks were estimated for an inception cohort of new ADD users using a 1 year lead‐in time. The full cohort was therefore restricted to patients starting with metformin or SU alone within the study period with at least 1 year without exposure to ADDs before the start of treatment (t 0). Study follow‐up for endpoints began at precisely the same time as initiation of therapy, or t 0. Data for all patient characteristics were obtained at time t 0.

The risk of UBC in different groups of ADD users was compared with SU only users. This analysis was stratified by ADD use: metformin alone (one), metformin in combination (two) with other ADD medication (glinides, glitazones, DPP‐4‐inhibitors, SUs, insulin or more than one combination), all metformin users (1 + 2). The estimates were adjusted for age, gender, smoking status and BMI and diabetes duration. The risk of UBC for patients with incident type 2 diabetes was further stratified by continuous duration (a gap of 30 days was allowed) of metformin intake and gender. A sensitivity analysis was carried out in the full cohort assessing the risk of UBC in the same groups of ADD users as the first analysis compared with SU only users. These estimates were adjusted for age, gender, smoking status, BMI and for retinopathy, neuropathy and HbA1c. Three more sensitivity analyses were carried out each time excluding cases of bladder cancer 180 days, 360 days and 720 days after ADD initiation (t 0) to explore the effect of pre‐existing cancer.

All data management and statistical analyses were conducted using SAS® 9.2 software.

This study was approved by the Medicines and Healthcare products Authorities' Independent Scientific Advisory Committee, protocol number 13_050R.

Results

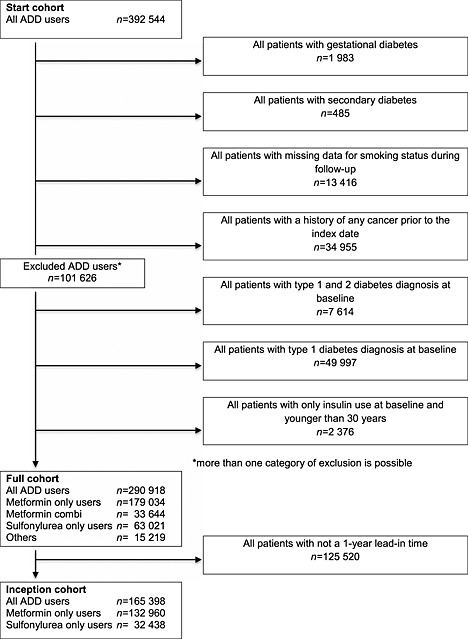

In total, 392 544 patients aged 18 years and older, were identified with at least one prescription for an ADD during the period of CPRD data collection (start cohort). After exclusion of 1983 patients with a diagnosis of gestational diabetes, 485 patients with secondary diabetes, 34 955 patients with cancer prior to index date, 13 416 patients with missing data for smoking status during follow‐up, 7614 patients diagnosed with type 1 and 2 diabetes at baseline, 49 997 patients with diagnosis of type 1 diabetes and 2376 patients with only insulin use at baseline and younger than 30 years, the full cohort consisted of 290 918 participants. Limiting the full cohort to incident ADD users with a 1 year lead‐in time, reduced the population further to 165 398 participants of which 132 960 were metformin users and 32 438 were SU only users (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study subjects

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of the inception cohort. SU users were older (66 years) at index date compared with the metformin users (58 years). Approximately 50% of the ADD users were non‐smokers. Sixty percent of the metformin only users had a BMI of 30 kg m−2 or above in contrast with only one fourth of the control subjects. A small percentage (around 3%) of the ADD users had already neuropathy and retinopathy at baseline.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of incident ADD users (inception cohort)

| Sulfonylurea (SU) † only users | Metformin only users | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | n = 32 438 | (%) | n = 132 960 | (%) |

| Follow‐up time (years) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 7.6 | (5.2) | 5.3 | (3.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 7.0 | (3.0–11.6) | 4.6 | (2.2–7.7) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 13 817 | (42.6) | 63 709 | (47.9) |

| Male | 18 621 | (57.4) | 69 251 | (52.1) |

| Age at index date (years) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 66.0 | (13.2) | 58.3 | (14.8) |

| Median | 67 | 60 | ||

| By category | ||||

| 18–29 | 157 | (0.5) | 5756 | (4.3) |

| 30–39 | 849 | (2.6) | 9825 | (7.4) |

| 40–49 | 2828 | (8.7) | 18 976 | (14.3) |

| 50–59 | 5920 | (18.3) | 31 562 | (23.7) |

| 60–69 | 8777 | (27.1) | 34 996 | (26.3) |

| 70–79 | 8900 | (27.4) | 23 745 | (17.9) |

| 80+ | 5007 | (15.4) | 8100 | (6.1) |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never smoker | 16 615 | (51.2) | 63 371 | (47.7) |

| Current smoker | 6248 | (19.3) | 25 146 | (18.9) |

| Former smoker | 9575 | (29.5) | 44 443 | (33.4) |

| Body mass index (kg m−2) | ||||

| <20 | 1054 | (3.2) | 921 | (0.7) |

| 20–24.9 | 8768 | (27.0) | 11 197 | (8.4) |

| 25–39.9 | 12 718 | (39.2) | 39 402 | (29.6) |

| > = 30 | 8512 | (26.2) | 79 758 | (60.0) |

| Unknown | 1386 | (4.3) | 1682 | (1.3) |

| HbA1c on index date (mean (SD)) | 9.2 | (2.1) | 8.5 | (1.8) |

| History of complications | ||||

| Neuropathy | 829 | (2.6) | 4574 | (3.4) |

| Retinopathy | 953 | (2.9) | 4551 | (3.4) |

Incident, all index patients are included after 1 year lead‐in time without anti‐diabetic drugs (ADD) prescription; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

Glibenclamide, gliclazide, glimepiride, glipizide, gliquidon.

Due to the large sample sizes, all analyses of baseline characteristics are statistically significant.

During a mean follow‐up of more than 5 years 693 patients developed UBC, 124 of the control group and 461 of the all metformin users (Table 2). There was no association between metformin use and UBC risk (HR = 1.12, 95% CI 0.90, 1.40) compared with SU only users, even after adjustment for diabetes duration (HR = 1.13, 95% CI 0.90, 1.40). The results (HR = 1.05, 95% CI 0.89, 1.24) for ADD users in the full cohort were similar (Table 3). Adjustment for history of complications (neuropathy, retinopathy) and the severity of diabetes (HbA1c) did not alter the risk (Table 3).

Table 2.

Risk of bladder cancer in incident metformin users compared with incident sulfonylurea (SU) only users

| Exposure category | Bladder cancer n = 693 | Age/gender adj HR | Adj HR (95% CI) † | Adj HR (95% CI) ‡ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | |||||||||

| SU only use | 124 | Reference | |||||||

| All metformin users (1 + 2) | 461 | 1.15 | (0.92, 1.43) | 1.12 | (0.90, 1.40) | 1.13 | (0.90, 1.40) | ||

| Metformin only users (1) | 247 | 1.08 | (0.86, 1.37) | 1.06 | (0.84, 1.34) | 1.03 | (0.81, 1.31) | ||

| Metformin in combination users (2) | 214 | 1.23 | (0.97, 1.56) | 1.21 | (0.95, 1.54) | 1.27 | (0.99, 1.62) | ||

| Metformin with SUs | 129 | 1.24 | (0.95, 1.60) | 1.22 | (0.94, 1.58) | 1.27 | (0.97, 1.65) | ||

| Metformin with glinides § | <5 events | 1.83 | (0.45, 7.41) | 1.80 | (0.44, 7.32) | 1.87 | (0.46, 7.59) | ||

| Metformin with glitazones ¶ | 23 | 1.15 | (0.73, 1.83) | 1.12 | (0.71, 1.78) | 1.15 | (0.72, 1.83) | ||

| Metformin with DPP‐4 inhibitors * | 7 | 1.37 | (0.63, 2.99) | 1.33 | (0.61, 2.90) | 1.33 | (0.61, 2.91) | ||

| Metformin with insulin | 14 | 1.11 | (0.63, 1.94) | 1.07 | (0.61,1.89) | 1.19 | (0.67, 2.13) | ||

| Metformin with more than one combination | 39 | 1.27 | (0.87, 1.86) | 1.23 | (0.84, 1.81) | 1.33 | (0.90, 1.97) | ||

| Other ADD users | 58 | 1.53 | (1.11, 2.12) | 1.52 | (1.10, 2.10) | 1.57 | (1.13, 2.19) | ||

| Insulin only | 26 | 1.77 | (1.15, 2.72) | 1.75 | (1.14, 2.69) | 1.92 | (1.24, 2.99) | ||

| Glitazones only | <5 events | 1.02 | (0.38, 2.79) | 1.01 | (0.37, 2.76) | 1.03 | (0.38, 2.81) | ||

| DPP‐4‐inhibitors only | <5 events | 2.37 | (0.75, 7.53) | 2.31 | (0.73, 7.34) | 2.29 | (0.72, 7.29) | ||

| Glinides only | <5 events | 2.05 | (0.29, 14.71) | 2.09 | (0.29,14.98) | 2.14 | (0.30, 15.31) | ||

| SUs combined (not with metformin) | 21 | 1.29 | (0.81, 2.07) | 1.28 | (0.80, 2.06) | 1.37 | (0.85, 2.20) | ||

| Others | <5 events | 2.44 | (0.77, 7.71) | 2.40 | (0.76, 7.59) | 2.58 | (0.81, 8.20) | ||

| Past SU user (not metformin with SU) | 16 | 0.66 | (0.39, 1.11) | 0.67 | (0.39, 1.12) | 0.68 | (0.40, 1.14) | ||

| Past metformin user (e.g. only insulin) | 23 | 0.54 | (0.34, 0.86) | 0.52 | (0.33,0.83) | 0.52 | (0.33, 0.83) | ||

| Past other | 11 | 0.37 | (0.20, 0.69) | 0.36 | (0.19, 0.67) | 0.37 | (0.20, 0.70) | ||

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; Incident, all index patients are included after 1 year lead‐in time without anti‐diabetic drugs (ADD) prescription; SU, glibenclamide, gliclazide, glimepiride, glipizide, gliquidon.

Adjusted for age, gender, smoking and BMI.

Adjusted for † and duration of diabetes.

Repaglinide.

Pioglitazone, rosiglitazone.

Saxagliptin, sitagliptin, vildagliptin.

Table 3.

Risk of bladder cancer in metformin users compared with sulfonylurea (SU) only users as controls (full cohort)

| Exposure category | Bladder cancer | Age/gender adj HR | Adj HR (95% CI) † | Adj HR (95% CI) ‡ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 1196 | (95% CI) | ||||||||

| SU only use | 219 | Reference | |||||||

| All metformin users (1 + 2) | 760 | 1.07 | (0.91, 1.26) | 1.04 | (0.88, 1.23) | 1.04 | (0.88, 1.23) | ||

| Metformin only users (1) | 299 | 0.95 | (0.79, 1.15) | 0.92 | (0.76, 1.11) | 0.92 | (0.76, 1.11) | ||

| Metformin in combination users (2) | 461 | 1.16 | (0.98, 1.38) | 1.14 | (0.96, 1.35) | 1.13 | (0.95, 1.35) | ||

| Metformin with SUs | 253 | 1.12 | (0.93, 1.35) | 1.10 | (0.91, 1.33) | 1.10 | (0.91, 1.33) | ||

| Metformin with glinides § | 6 | 1.90 | (0.84, 4.29) | 1.86 | (0.82, 4.19) | 1.86 | (0.82, 4.20) | ||

| Metformin with glitazones ¶ | 40 | 1.14 | (0.80, 1.61) | 1.09 | (0.77, 1.54) | 1.09 | (0.77, 1.54) | ||

| Metformin with DPP‐4 inhibitors * | 7 | 0.93 | (0.44, 2.00) | 0.89 | (0.41, 1.91) | 0.89 | (0.42, 1.91) | ||

| Metformin with insulin | 59 | 1.23 | (0.91, 1.65) | 1.20 | (0.89, 1.61) | 1.18 | (0.88, 1.60) | ||

| Metformin with more than one combination | 96 | 1.26 | (0.98, 1.62) | 1.23 | (0.95, 1.59) | 1.23 | (0.95, 1.59) | ||

| Other ADD users | 143 | 1.20 | (0.97, 1.50) | 1.13 | (0.91, 1.40) | 1.11 | (0.89, 1.38) | ||

| Insulin only | 74 | 1.00 | (0.77, 1.31) | 1.01 | (0.77, 1.31) | 0.99 | (0.76, 1.30) | ||

| Glitazones only | 8 | 1.01 | (0.50, 2.06) | 0.98 | (0.48, 2.00) | 0.99 | (0.48, 2.01 | ||

| DPP‐4‐inhibitors only | <5 events | 1.48 | (0.47, 4.65) | 1.43 | (0.45, 4.50) | 1.43 | (0.45, 4.50) | ||

| Glinides only | <5 events | 2.03 | (0.65, 6.35) | 2.05 | (0.66, 6.42) | 2.05 | (0.65, 6.41) | ||

| SU combined (not with metformin) | 48 | 1.29 | (0.94, 1.78) | 1.28 | (0.93, 1.76) | 1.27 | (0.93, 1.75) | ||

| Others | 7 | 1.73 | (0.81, 3.69) | 1.68 | (0.79, 3.58) | 1.67 | (0.78, 3.56) | ||

| Past SU user (not metformin with SU) | 27 | 0.67 | (0.45, 0.99) | 0.67 | (0.45, 1.01) | 0.68 | (0.45, 1.01) | ||

| Past metformin user (e.g. only insulin) | 28 | 0.49 | (0.33, 0.73) | 0.47 | (0.32, 0.71) | 0.48 | (0.32, 0.71) | ||

| Past other | 19 | 0.28 | (0.17, 0.44) | 0.27 | (0.17, 0.44) | 0.27 | (0.17, 0.44) | ||

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; Incident, all index patients are included after 1 year lead‐in time without anti‐diabetic drugs (ADD) prescription; SU, glibenclamide, gliclazide, glimepiride, glipizide, Gliquidon.

Adjusted for age, gender, smoking and BMI.

Adjusted for † and retinopathy, neuropathy and HbA1c.

Repaglinide.

Pioglitazone, rosiglitazone.

Saxagliptin, sitagliptin, vildagliptin.

For incident metformin users, we noticed a non‐significant increased risk of UBC (HR = 1.14, 95% CI 0.88, 1.48) during the first year after the first ADD prescription, compared to controls, disappearing in subsequent years (Table 4). There was a not significant linear association between the risk of bladder cancer over time (P trend =0.07). There was no difference in UBC risk between male and female metformin users (HR = 1.12, 95% CI 0.86, 1.47 and 0.86, 95% CI 0.52, 1.42, respectively).

Table 4.

Risk of bladder cancer in incident metformin only users compared with controls, by duration of metformin only intake and gender

| Exposure category | Bladder cancer n = 693 | Age/gender adj HR | Adj HR (95% CI) † | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | |||||

| SU only use | 124 | Reference | |||

| All metformin users | 461 | 1.15 | (0.92, 1.43) | 1.12 | (0.90, 1.40) |

| Metformin only users | 247 | 1.08 | (0.86, 1.37) | 1.06 | (0.84, 1.34) |

| By continuous duration of metformin intake ‡ | |||||

| No continuous duration | 10 | 1.46 | (0.76, 2.81) | 1.42 | (0.74, 2.72) |

| < 1 year | 144 | 1.17 | (0.91, 1.51) | 1.14 | (0.88, 1.48) |

| ≥ 1–2 years | 45 | 1.11 | (0.78, 1.57) | 1.08 | (0.76, 1.54) |

| ≥ 2–3 years | 21 | 0.91 | (0.57, 1.46) | 0.89 | (0.55, 1.43) |

| ≥ 3–4 years | 10 | 0.72 | (0.38, 1.39) | 0.71 | (0.37, 1.35) |

| ≥ 4–5 years | 6 | 0.71 | (0.31, 1.62) | 0.69 | (0.30, 1.58) |

| ≥ 5 years | 11 | 0.89 | (0.47, 1.66) | 0.87 | (0.46, 1.63) |

| Gender | |||||

| Male § | 1.16 | (0.88, 1.51) | 1.12 | (0.86, 1.47) | |

| Female ¶ | 0.85 | (0.52, 1.40) | 0.86 | (0.52, 1.42) | |

| Metformin in combination users | 214 | 1.23 | (0.97, 1.56) | 1.21 | (0.95, 1.54) |

| Other ADD users | 58 | 1.53 | (1.11, 2.12) | 1.52 | (1.10, 2.10) |

| Past SU user (not metformin with SU) | 16 | 0.66 | (0.39, 1.11) | 0.67 | (0.39, 1.12) |

| Past metformin user (e.g. only insulin) | 23 | 0.54 | (0.34, 0.86) | 0.52 | (0.33, 0.83) |

| Past other | 11 | 0.37 | (0.20, 0.69) | 0.36 | (0.19, 0.67) |

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; Incident, all index patients are included after I year lead‐in time without anti‐diabetic drugs (ADD) prescription; SU, glibenclamide, gliclazide, glimepiride, glipizide, gliquidon.

Adjusted for age, gender, smoking and BMI.

As measured from first prescription, gaps of 30 days are allowed.

Male metformin users vs. male controls.

Female metformin users vs. female controls.

Discussion

We found no association between incident metformin users and UBC risk compared with incident SU users. Even if there was a pattern of decreasing risk of UBC with increasing duration of metformin intake, it was not statistically significant. Our results were in line with the findings of a similar study, the UK Inception Cohort Study using The Health Improvement Network database 30.

We showed that the metformin users were on average younger than the SU users (58 vs. 66.8 years) and more obese (nearly 60% had a BMI above 30 kg m−2). These findings confirm that metformin is the first choice for obese type 2 diabetes patients because metformin offers glucose lowering with some weight loss 10, 31.

Although this study has many strengths, there are several limitations. The CPRD is a large population‐based cohort representative of the total UK population. Consulting rates for diabetes in the CPRD have been compared with equivalent data from the 4th National Morbidity Survey in General Practice confirming the validity of the morbidity data in the CPRD 29. Since 2004, GPs are stimulated to provide ‘quality care’ by the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF). The UK has a National Service Framework (NSF) for Diabetes 32. Guidelines to be followed by the GPs are outlined in the guideline for type 2 diabetes 10 of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Although guidelines for the treatment of type 2 diabetes have changed over time, the general approach has remained fairly consistent: blood glucose lowering therapy is started in a step‐up system if HbA1c is equal to or more than 6.5% after lifestyle interventions. The first step is monotherapy with metformin or SU. In a second step, dual and even triple therapy of NIAD which may be combined with insulin therapy, and ultimately insulin monotherapy are used if HbA1c is still equal to or more than 6.5% 10, 33, 34.

The CPRD comprises electronic medical records from British GPs. Diagnosis of bladder cancer depends on the registration of this diagnosis in the database by the GP and patients can be subject to non‐adherence of their therapy. So, underestimation of bladder cancer cases is possible, but should be equal in both groups. Despite the fact that the CPRD contains data from over 10 million patients, bladder cancer patients are still limited as is the follow‐up time. The median follow‐up time of metformin only users is 4.6 years with a maximum of 7.7 years. Diabetes patients are on metformin alone during a limited time of their disease. As their diabetes progresses, a combination of ADDs may be necessary.

We were able to collect a large inception cohort of type 2 diabetes patients (n = 165 398) reducing our cohort to all new patients with a formal type 2 diabetes diagnosis or ADD use. All analyzed patients had data on smoking status, the main confounder for bladder cancer. Although this cohort still contained 12 841 women with diagnosis of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), rare off‐label indications are unlikely affect pharmacological hypothesis. A sensitivity‐analysis excluding these PCOS patients estimating the risk of bladder cancer in diabetes patients compared with non‐diabetes controls did not alter the results in the same cohort of diabetic patients 6. We preferred to use an inception cohort instead of a nested case–control design. While the nested case–control design allows for statistically efficient analysis of data from a cohort with substantial savings in cost and time especially when a lot of covariates are included in the model for more rare diseases in databases 35, using a new user design consistently avoids time‐related biases as described by Suissa & Azouly 23. Immortal time has been avoided by including patients as new users of metformin or SU after a 1 year lag period before enrolment in the inception cohort. Both drugs are first line treatment for type 2 diabetes, so both groups are in the same stage of their disease avoiding time lag bias by comparing first line treatment with second or third line treatments. Metformin and SU use have been analyzed in a time‐dependent way. The different continuous duration of metformin intake was compared with the same strata of SU only use to avoid time‐window bias. Whereas the nested case–control approach is described by Essebag et al. 35 as a useful alternative for cohort analysis when studying time‐dependent exposures compared with Cox regression including time‐dependent covariates, in reality there are still differences. Both Azoulay et al. 36 and Wei et al. 37 estimated the risk of bladder cancer in patients with type 2 diabetes exposed to pioglitazone in the CPRD respectively conducting a nested case–control study and a propensity score matched cohort study and reporting, respectively, an increased risk (rate ratio = 1.83, 95% CI 1.10, 3.05) and a not increased rate (HR = 1.16, 95% CI 0.83, 1.62).

A possible shortcoming of this study is that we did not evaluate the exposure to metformin or SU by cumulative dosage. Patients with sporadic use of metformin were analyzed in the first duration category (< 1 year), and compared with the same category of SU users.

With this study we were able to confirm that time‐related bias could be an explanation of the anti‐cancer effect of metformin noticed in many epidemiological studies. However, there is still the plausibility for metformin as an anti‐cancer drug in laboratory models 7 even if some of these experiments were done with concentrations exceeding those achieved with conventional doses used for diabetes treatment 38. Furthermore, a first pilot clinical trial using metformin 500 mg daily in patients with endometrial cancer from diagnostic biopsy to surgery, presented biological evidence consistent with anti‐proliferative effects of metformin in the clinical setting 39. The results of similar studies done in breast cancer were inconsistent 38. Nevertheless, trials using more aggressive doses of biguanides or using novel biguanides may be expected in the future 40.

We noticed a non‐significantly increased risk of UBC (HR = 1.14, 95% CI 0.88, 1.48) during the first year after the first ADD prescription, compared with controls. A same increase in risk has been seen after diabetes diagnosis 6 most likely indicating the presence of detection bias. The sensitivity analyses inducing a time lag period of 180, 360 or 720 days did not confirm the hypothesis that the increased risk detected during the first year was due to metformin (HR = 1.11, 95% CI 0.84, 1.47 for 360 days time lag period).

After avoiding all time‐related biases, we could not detect a protective effect of metformin for the risk of UBC. The effect of metformin on the recurrence and progression of UBC was beyond the scope of this study and requires further investigation.

In conclusion, metformin has no influence on the risk of UBC compared with sulfonylurea in type 2 diabetes patients using a new user design.

Competing Interests

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare no support from any organization for the submitted work, no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work1.

The research leading to the results of this study has received funding from the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme (FP‐7) under grant agreement number 282 526, the CARING project. The funding source had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report.

Contributors

ME.G. wrote the manuscript and researched data. J.D. performed the statistical analysis and reviewed the manuscript. F.B. and MP.Z. reviewed/edited the manuscript. F.dV. and ML.DB. provided the data and reviewed/edited the manuscript.

Data sharing statement

CPRD data are available under license with the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) in London, UK. The datasets which have been used for this project have been licensed by the MHRA. Access to datasets that have been used for this study are available for audit purposes only, conditional upon permission by the MHRA.

Goossens, M. E. , Buntinx, F. , Zeegers, M. P. , Driessen, J. H. M. , De Bruin, M. L. , and De Vries, F. (2015) Influence of metformin intake on the risk of bladder cancer in type 2 diabetes patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 80: 1464–1472. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12740.

References

- 1. International Diabetes Federation . IDF Diabetes Atlas, 6th edn Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation, 2014. Available at http://www.idf.org/diabetesatlas [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin D, Forman D, Bray F. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 [Internet]. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2013. Available at http://globocan.iarc.fr [Google Scholar]

- 3. Larsson SC, Orsini N, Brismar K, Wolk A. Diabetes mellitus and risk of bladder cancer: a meta‐analysis. Diabetologia 2006; 49: 2819–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhu Z, Zhang X, Shen Z, Zhong S, Wang X, Lu Y, Xu C. Diabetes mellitus and risk of bladder cancer: a meta‐analysis of cohort studies. PLoS One 2013; 8: e56662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xu X, Wu J, Mao Y, Zhu Y, Hu Z, Xu X, Lin Y, Chen H, Zheng X, Qin J, Xie L. Diabetes mellitus and risk of bladder cancer: a meta‐analysis of cohort studies. PLoS One 2013; 8: e58079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Goossens ME, Zeegers MP, Bazelier MT, De Bruin ML, Buntinx F, de Vries F. Risk of bladder cancer in patients with diabetes: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2015; 5:e007470. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kasznicki J, Sliwinska A, Drzewoski J. Metformin in cancer prevention and therapy. Ann Transl Med 2014; 2: 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. ClinicalTrials.gov . A service of the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Available at https://clinicaltrials.gov (last accessed 14 April 2015).

- 9. International Diabetes Federation . IDF Global Guideline for type 2 Diabetes. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation, 2012. Available at http://www.idf.org/diabetesatlas [Google Scholar]

- 10. Type 2 diabetes | Guidance and guidelines | NICE. Available at http://wwwniceorguk/guidance/cg87 2009 (last accessed 19 March 2015).

- 11. Malek M, Aghili R, Emami Z, Khamseh ME. Risk of cancer in diabetes: the effect of metformin. ISRN Endocrinol 2013; 2013: 636927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Franciosi M, Lucisano G, Lapice E, Strippoli GF, Pellegrini F, Nicolucci A. Metformin therapy and risk of cancer in patients with type 2 diabetes: systematic review. PLoS One 2013; 8: e71583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Libby G, Donnelly LA, Donnan PT, Alessi DR, Morris AD, Evans JM. New users of metformin are at low risk of incident cancer: a cohort study among people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009; 32: 1620–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ngwana G, Aerts M, Truyers C, Mathieu C, Bartholomeeusen S, Wami W, Buntinx F. Relation between diabetes, metformin treatment and the occurrence of malignancies in a Belgian primary care setting. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2012; 97: 331–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tseng CH. Metformin may reduce bladder cancer risk in Taiwanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Acta Diabetol 2014; 51: 295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yin M, Zhou J, Gorak EJ, Quddus F. Metformin is associated with survival benefit in cancer patients with concurrent type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Oncologist 2013; 18: 1248–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bowker SL, Majumdar SR, Veugelers P, Johnson JA. Increased cancer‐related mortality for patients with type 2 diabetes who use sulfonylureas or insulin. Diabetes Care 2006; 29: 254–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang T, Guo P, Zhang Y, Xiong H, Yu X, Xu S, Wang X, He D, Jin X. The antidiabetic drug metformin inhibits the proliferation of bladder cancer cells in vitro and in vivo . Int J Mol Sci 2013; 14: 24603–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang T, Wang X, He D, Jin X, Guo P. Metformin sensitizes human bladder cancer cells to TRAIL‐induced apoptosis through mTOR/S6K1‐mediated downregulation of c‐FLIP. Anticancer Drugs 2014; 25: 887–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rieken M, Xylinas E, Kluth L, Crivelli JJ, Chrystal J, Faison T, Lotan Y, Karakiewicz PI, Fajkovic H, Babjuk M, Kautzky‐Willer A, Bachmann A, Scherr DS, Shariat SF. Association of diabetes mellitus and metformin use with oncological outcomes of patients with non‐muscle‐invasive bladder cancer. BJU Int 2013; 112: 1105–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rieken M, Xylinas E, Kluth L, Crivelli JJ, Chrystal J, Faison T, Lotan Y, Karakiewicz PI, Sun M, Fajkovic H, Babjuk M, Bachmann A, Scherr DS, Shariat SF. Effect of diabetes mellitus and metformin use on oncologic outcomes of patients treated with radical cystectomy for urothelial carcinoma. Urol Oncol 2014; 32: 49 e7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stevens RJ, Ali R, Bankhead CR, Bethel MA, Cairns BJ, Camisasca RP, Crowe FL, Farmer AJ, Harrison S, Hirst JA, Home P, Kahn SE, McLellan JH, Perera R, Pluddemann A, Ramachandran A, Roberts NW, Rose PW, Schweizer A, Viberti G, Holman RR. Cancer outcomes and all‐cause mortality in adults allocated to metformin: systematic review and collaborative meta‐analysis of randomised clinical trials. Diabetologia 2012; 55: 2593–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Suissa S, Azoulay L. Metformin and the risk of cancer: time‐related biases in observational studies. Diabetes Care 2012; 35: 2665–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ray WA. Evaluating medication effects outside of clinical trials: new‐user designs. Am J Epidemiol 2003; 158: 915–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vandenbroucke JP. The HRT controversy: observational studies and RCTs fall in line. Lancet 2009; 373: 1233–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Robinson D, Schulz E, Brown P, Price C. Updating the Read Codes: user‐interactive maintenance of a dynamic clinical vocabulary. J Am Med Inform Assoc 1997; 4: 465–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. NHS . Prescription Services BNF Classification and Pseudo Classification used by the NHS Prescription Services. Incorporating changes up to and including BNF Number 66 2013.

- 28. Herrett E, Thomas SL, Schoonen WM, Smeeth L, Hall AJ. Validation and validity of diagnoses in the General Practice Research Database: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2010; 69: 4–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hollowell J. The General Practice Research Database: quality of morbidity data. Popul Trends 1997; 87: 36–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mamtani R, Pfanzelter N, Haynes K, Finkelman BS, Wang X, Keefe SM, Haas NB, Vaughn DJ, Lewis JD. Incidence of bladder cancer in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with metformin or sulfonylureas. Diabetes Care 2014; 37: 1910–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhao Q, Marcy TR. Incretin‐based therapy compared with non‐insulin alternatives in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes. Consult Pharm 2013; 28: 515–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. National Service Framework for Diabetes . Department of Health 2001 .

- 33. International Diabetes Federation . IDF Diabetes Atlas, 6th edn Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation, 2013. Available at http://www.idf.org/diabetesatlas [Google Scholar]

- 34. Scheen AJ. Drug treatment of non‐insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus in the 1990s. Achievements and future developments. Drugs 1997; 54: 355–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Essebag V, Platt RW, Abrahamowicz M, Pilote L. Comparison of nested case–control and survival analysis methodologies for analysis of time‐dependent exposure. BMC Med Res Methodol 2005; 5: 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Azoulay L, Yin H, Filion KB, Assayag J, Majdan A, Pollak MN, Suissa S. The use of pioglitazone and the risk of bladder cancer in people with type 2 diabetes: nested case‐control study. BMJ 2012; 344: e3645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wei L, MacDonald TM, Mackenzie IS. Pioglitazone and bladder cancer: a propensity score matched cohort study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2013; 75: 254–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pollak MN. Investigating metformin for cancer prevention and treatment: the end of the beginning. Cancer Discov 2012; 2: 778–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Laskov I, Drudi L, Beauchamp MC, Yasmeen A, Ferenczy A, Pollak M, Gotlieb WH. Anti‐diabetic doses of metformin decrease proliferation markers in tumors of patients with endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2014; 134: 607–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pollak M. Metformin's potential in oncology. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol 2013; 11: 594–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]