Abstract

Aims

LDL‐receptor expression is inhibited by the protease proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9), which is considered a pharmacological target to reduce LDL‐C concentrations in hypercholesterolaemic patients. We performed a first‐in‐human trial with SPC5001, a locked nucleic acid antisense inhibitor of PCSK9.

Methods

In this randomized, placebo‐controlled trial, 24 healthy volunteers received three weekly subcutaneous administrations of SPC5001 (0.5, 1.5 or 5 mg kg–1) or placebo (SPC5001 : placebo ratio 6 : 2). End points were safety/tolerability, pharmacokinetics and efficacy of SPC5001.

Results

SPC5001 plasma exposure (AUC(0,24 h)) increased more than dose‐proportionally. At 5 mg kg–1, SPC5001 decreased target protein PCSK9 (day 15 to day 35: −49% vs. placebo, P < 0.0001), resulting in a reduction in LDL‐C concentrations (maximal estimated difference at day 28 compared with placebo −0.72 mmol l–1, 95% confidence interval − 1.24, −0.16 mmol l–1; P < 0.01). SPC5001 treatment (5 mg kg–1) also decreased ApoB (P = 0.04) and increased ApoA1 (P = 0.05). SPC5001 administration dose‐dependently induced mild to moderate injection site reactions in 44% of the subjects, and transient increases in serum creatinine of ≥20 μmol l–1 (15%) over baseline with signs of renal tubular toxicity in four out of six subjects at the highest dose level. One subject developed biopsy‐proven acute tubular necrosis.

Conclusions

SPC5001 treatment dose‐dependently inhibited PCSK9 and decreased LDL‐C concentrations, demonstrating human proof‐of‐pharmacology. However, SPC5001 caused mild to moderate injection site reactions and renal tubular toxicity, and clinical development of SPC5001 was terminated. Our findings underline the need for better understanding of the molecular mechanisms behind the side effects of compounds such as SPC5001, and for sensitive and relevant renal toxicity monitoring in future oligonucleotide studies.

Keywords: antisense, hypercholesterolaemia, LDL‐C, PCSK9, SPC5001

What is Already Known About this Subject

Pharmacological inhibition of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) by monoclonal antibodies and small molecules seems to be safe and effective in treating hypercholesterolaemia.

The safety and efficacy of locked nucleic acid antisense oligonucleotides targeting PCSK9 has not been studied before.

What this Study Adds

In this first‐in‐human study, locked nucleic acid antisense oligonucleotide SPC5001 dose‐dependently reduced LDL‐C and PCSK9, but treatment was associated with injection site reactions and transient renal tubular toxicity at the highest dose tested.

Our findings provide detailed insight into the side effects of one oligonucleotide treatment and underline the need for better understanding of the molecular mechanisms behind the side effects of such compounds.

Our findings demonstrate the need for sensitive and tailored renal toxicity monitoring in future oligonucleotide studies.

Introduction

Statin therapy is one of the best‐proven interventions in patients at high risk for cardiovascular disease. However, target low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C) goal concentrations are not always reached. Increasing statin dose to achieve lower LDL‐C concentrations may cause adverse events such as skeletal muscle aches and increases in liver enzymes and, very rarely, rhabdomyolysis 1. Hence, novel treatments to reduce LDL‐C with a different mechanism of action could be of value. Modulation of LDL‐receptor (LDL‐R) expression is an attractive mechanism as LDL‐C concentrations depend largely on expression and activity of the hepatic LDL‐R 2. Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) is a protease that mediates endosomal/lysosomal degradation of the LDL‐R by prolonging its retention in endosomes, resulting in reduced LDL‐R recycling to the cell surface 3. Gain‐of‐function mutations in PCSK9 are associated with a severe phenotype of autosomal dominant familial hypercholesterolaemia 4, whereas loss‐of‐function mutations can result in a 30% lowering of LDL‐C 5 and a 47–88% reduction in cardiovascular disease risk 6 in the absence of any other apparent phenotypic change in humans 7. Preclinical data have shown that inhibition of PCSK9 results in reduction of serum LDL‐C concentrations 8, 9, and recent clinical studies have demonstrated PCSK9‐antibody mediated reductions in LDL‐C concentrations and cardiovascular events 10, 11.

SPC5001 is a 14‐mer oligonucleotide with locked nucleic acid (LNA) modifications. The oligonucleotide contains β‐D‐oxy‐LNA (three locked nucleotides in both termini), and eight deoxynucleotides, arranged in the sequence 5′‐TGmCtacaaaacmCmCA‐3′ (where upper case letters are LNAs and mC stands for 5‐methyl‐LNA‐cytidine). Each of the internucleotide linkages is modified with phosphorothioate rather than the native phosphodiester. The LNA modified nucleotides increase the binding affinity for the target and increase nuclease resistance, thereby improving the drug‐like properties 12. SPC5001 is complementary to human PCSK9 mRNA, acts as an antisense inhibitor, and subsequently reduces intra‐ and extracellular PCSK9 protein levels 8. Subcutaneously (s.c.) administered SPC5001 for 13 weeks in mice (maximal dose 24 mg kg–1 week–1) and non‐human primates (NHP) (maximal maintenance dose 20 mg kg–1 week–1) demonstrated no rate‐limiting toxicity on liver and kidney function, only minimal s.c. injection site reactions and no effect on coagulation parameters (Santaris Pharma A/S preclinical package, data not shown). As with other antisense oligonucleotide (AON) compounds, renal histopathology showed tubular basophilic granules suggestive of oligonucleotide drug accumulation at SPC5001 dose levels up to 20/24 mg kg–1, without signs of functional nephrotoxicity. The maximum safe starting dose for clinical testing of SPC5001 was 2.0 mg kg–1 week–1, based on the absence of adverse effects at the highest dose tested in a 13 week NHP study (20 mg kg–1). Administration of four SPC5001 doses of 6 mg kg–1 resulted in reductions of plasma PCSK9 protein concentrations (37%), hepatic PCSK9 mRNA levels (40%), and serum lipids (32%) in healthy NHPs. A lower dose of 1.5 mg kg–1, administered once every 5 days, also induced significant reductions in LDL‐C (16%), but not in plasma PCSK9. Based on these observations, three weekly SPC5001 injections of 0.5 mg kg–1 were considered to be an appropriate starting dose for a first‐in‐human (FIH) trial, on which we report here. Ascending doses of SPC5001 were administered to healthy volunteers with slightly increased fasting LDL‐C concentrations (exceeding 2.59 mmol l–1 or 100 mg dl–1), with a view to enable assessment of the human pharmacology of SPC5001 at the earliest clinical stage. Plasma PCSK9 concentrations and key lipid parameters were evaluated, together with standard safety end points and pharmacokinetic profiling.

Methods

Study design

The study was randomized, ascending dose, double‐blind and placebo‐controlled, with an SPC5001 : placebo ratio of 6 : 2 per cohort conducted at the foundation Centre for Human Drug Research, Leiden, The Netherlands. Given the exploratory character of the study, no formal power calculations were performed to assess sample size. Drug was administered subcutaneously in the abdominal region as three weekly doses of 0.5, 1.5 or 5 mg kg–1 on study days 1, 8 and 15 (150 mg ml–1 SPC5001 dissolved in water for injection; injection volumes ≤3 ml administered in a single injection and volumes >3 ml in two injections). The starting dose of 0.5 mg kg–1 week–1 was 4‐fold lower than the maximum recommended starting dose of 2.0 mg kg–1 week–1, based on a NOAEL of 20 mg kg–1 per dose in NHPs and a human equivalent dose (HED) of 20 mg kg–1 per dose, with an applied safety factor of 10. After the first and last SPC5001 or placebo (0.9% saline) administration, the subjects were confined to the clinical research unit for 24 h. After the second administration the subjects were monitored for 4 h. The last follow‐up visit was conducted on study day 78.

Study participants

Thirty‐two healthy volunteers, aged 18 to 65 years with a fasting LDL‐C of ≥2.59 mmol l–1 (≥ 100 mg dl–1) and triglycerides ≤4.5 mmol l–1 (≤ 398 mg dl–1), a body mass index (BMI) of 18–33 kg m–2, without ultrasonographic signs of liver steatosis and not using concomitant medication, were planned to be enrolled in four subsequent cohorts. The study was approved by the Central Committee on Research involving Human Subjects of The Netherlands (Centrale Commissie Mensgebonden Onderzoek; CCMO, EudraCT number of the study is 2011–000 489–36), and conducted according to the principles of the International Conference on Harmonization and Good Clinical Practice and the Helsinki Declaration. The volunteers gave written informed consent prior to screening.

Safety and tolerability

Safety monitoring was performed by adverse event monitoring, physical examination, assessment of ECG and vital signs, and laboratory evaluations (routine haematology, chemistry including C‐reactive protein and gamma globulins, coagulation, complement factors, cytokines, and semi quantitative dipstick urinalysis). In case of clinically significant findings in dipstick analysis, a microscopic investigation of the urine was performed. Hepatic ultrasonography (Siemens P50) was performed at screening and the last follow‐up visit for exclusion of hepatic steatosis. Dosing for each subsequent cohort commenced only after satisfactory review of 16 day safety data from the preceding cohort.

Post hoc analysis of exploratory kidney injury biomarkers was performed for urinary β2‐microglobulin (Immulite® 2000, a solid‐phase two‐side chemiluminescent immunometric assay), α‐GST (Argutus Medical Alpha GST EIA enzyme immunoassay), NAG (Diazyme Europe GmbH) and KIM‐1 (Quantikine® human TIM‐1/KIM‐1/HAVCR immunoassay). Samples for these biomarkers were collected on study days 1, 8 and 15 and stored at −80°C until analysis. Additional blood and urine samples were collected upon renal safety concerns that appeared during study conduct.

Pharmacodynamics

Throughout the study, pharmacodynamic effects of SPC5001 were assessed in fasting blood samples by measurement of PCSK9, TC, HDL‐C, TG, ApoA1, ApoB and VLDL‐C. Total (LDL‐bound and ‐unbound) PCSK9 was measured using the CircuLex human PCSK9 ELISA kit. The sensitivity was 0.154 ng l–1 and the coefficient of variation was ∼3%. LDL‐C was calculated according to the Friedewald formula: LDL‐C = TC – HDL‐C – (0.456*TG). VLDL‐C was calculated as TC – HDL‐C – LDL‐C.

Pharmacokinetics

For the quantification of SPC5001, plasma samples (collected frequently on dosing days 1 and 15, pre‐dose on day 8 and during follow‐up visits) were analyzed by a validated hybridization‐dependent ELISA method (Santaris Pharma A/S, Technical Report), with a lower limit of quantitation (LOQ) of 0.4 ng ml–1. The overall coefficient of variation was ~9%. In addition, urine samples collected on dosing days 1 and 15 (pre‐dose and 0–4, 4–8 and 8–24 h post‐dose) were analyzed by a comparable qualified method. SPC5001 plasma concentrations were subjected to non‐compartmental pharmacokinetic evaluation in order to determine the maximum observed plasma concentration (C max), the time to maximum plasma concentration (t max) and the area under the plasma concentration−time curve from dosing to 24 h after dosing (AUC(0,24h)) using WinNonLin (version 5.3, Pharsight Corporation, USA).

Urine was collected prior to dose and during 24 h after the first and the third doses (on days 1 and 15, respectively) from all subjects (except one subject dosed at 1.5 mg kg–1 per dose on day 15). The concentration of SPC5001 in the urine was quantified by the hybridization‐dependent ELISA method and the amount of the compound in relation to the dose was calculated.

Statistical methods and analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and baseline characteristics. Statistical analysis was performed for all pharmacodynamic parameters. To correct for the expected log‐normal distribution, PCSK9, HDL‐C, TG and VLDL‐C were log‐transformed prior to analysis. All repeatedly measured pharmacodynamic parameters were analyzed with a mixed model of variance with fixed factors treatment, time and treatment by time and random factor subject, and with the baseline measurement on day 1 as covariate. Contrasts between each SPC5001 dose level and placebo were calculated for a study period up to and including day 49 (the time span in which SPC5001 exerted the intended effects, at least at the highest dose level tested), unless otherwise indicated. All analyses were performed using SAS for Windows Version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Participant characteristics

Twenty‐four subjects were enrolled in the study. Demographics are summarized in Table 1. One subject in the 1.5 mg kg−1 dose group was withdrawn after administration of two SPC5001 doses due to non‐compliance with the study lifestyle rules. Therefore, 23 subjects completed the study, receiving three doses of SPC5001 or placebo.

Table 1.

Subject baseline demographics, average (SD)

| SPC5001 (n = 18) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 mg kg−1 (n = 6) | 1.5 mg kg−1 (n = 6) | 5 mgkg−1 (n = 6) | Placebo (n = 6) | |

| Gender (M : F) | 5 : 1 | 4 : 2 | 2 : 4 | 1 : 5 |

| Age (years) | 36 (14) | 52 (14) | 53 (15) | 50 (15) |

| Weight (kg) | 82 (11) | 73 (10) | 74 (16) | 70 (13) |

| BMI (kg m−2) | 25 (2) | 24 (3) | 25 (4) | 25 (3) |

| LDL‐C (mmol l−1) | 3.02 (0.56) | 4.00 (0.92) | 4.26 (0.73) | 3.82 (0.44) |

| Creatinine (μmol l−1) | 78 (14) | 84 (11) | 80 (14) | 70 (8) |

Safety summary

One patient dosed at the highest dose (5 mg kg−1 per dose) experienced acute tubular necrosis 11. Therefore, follow‐up was intensified for this subject and all other participants still under follow‐up. Upon review of elevated serum creatinine values together with urine sediment analyses, the Safety Review Committee decided to stop further dose escalation. For this reason, only 24 subjects were enrolled in the study and not the anticipated 32. In addition, a more comprehensive set of kidney injury biomarkers was retrospectively analyzed. The most frequent occurring adverse events were injection site reactions (ISR), observed in 44% of the SPC5001‐treated subjects and in none of the placebo‐treated subjects.

Renal effects

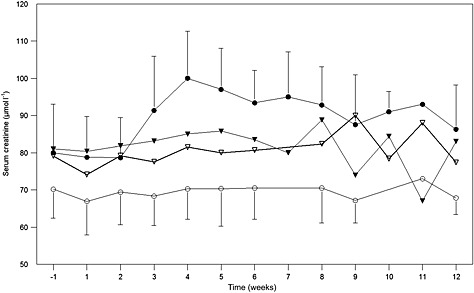

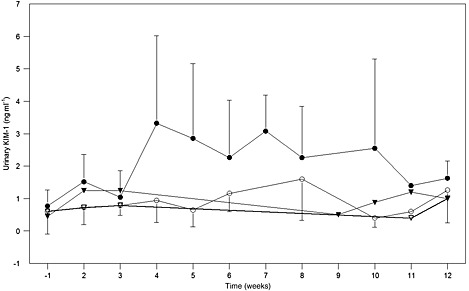

SPC5001 dose‐dependently increased serum creatinine. Whereas in the 0.5 and 1.5 mg kg−1 per dose groups no clinically relevant effects on serum creatinine levels were observed, SPC5001 treatment at 5 mg kg−1 per dose induced a transient increase in serum creatinine (Figure 1, Table 2, P = 0.02), which was observed in four out of six subjects. Average serum creatinine concentrations in that group started to increase after the last SPC5001 administration and peaked approximately 10 days after the final dose (from 84 ± 12 to 106 ± 15 μmol l–1; reference ranges are 64–104 μmol l–1 for males and 49–90 μmol l–1 for females). Subsequently, serum creatinine gradually declined to baseline levels. The rise in serum creatinine coincided with the appearance of urinary granular casts. In addition, one of the subjects developed acute tubular necrosis 5 days after the last SPC5001 administration, which has been described in detail in a case report 13. Upon appearance of these renal effects, additional blood and urinary samples were collected in all volunteers who were still under follow‐up. Both the scheduled samples (collected pre‐dose, and in weeks 1, 2 and 11) and the additional samples were analyzed for serum creatinine, urinary β2‐microglobulin, α‐glutathione S‐transferase (α‐GST), kidney injury molecule‐1 (KIM‐1) and N‐acetyl‐β‐D‐glucosaminidase (NAG). Increases in serum creatinine (9%), urinary β2‐microglobulin (200%), and urinary KIM‐1 (55%) were observed at the highest SPC5001 dose level tested (5 mg kg−1 week−1 for 3 weeks) (Table 2), with serum creatinine and urinary KIM‐1 reaching peak concentrations at the fourth week (Figures 1 and 2). However, the collection of these data was not balanced between the treatment groups.

Figure 1.

Average serum creatinine concentrations (μmol l−1), with SD bars. SPC5001 administration was on study days 1, 8 and 15. Averages include both scheduled and unscheduled samples, grouped by week. ( placebo,

placebo,  0.5 mg kg−1,

0.5 mg kg−1,  1.5 mg kg−1,

1.5 mg kg−1,  5mg kg−1)

5mg kg−1)

Table 2.

Serum creatinine and urinary kidney injury markers. Estimated differences between active treatment and placebo, calculated for scheduled samples over the complete study period of 78 days, expressed as % change, presented with 95% confidence interval and corresponding P value. n: number of samples analyzed, N: number of subjects

| 0.5 mg kg−1 SPC5001 vs. placebo N = 6 | 1.5 mg kg−1 SPC5001 vs. placebo N = 6 | 5 mg kg−1 SPC5001 vs. placebo N = 6 | Placebo Average (SD) N = 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum creatinine (μmol l−1) | 7.0% | 7.5% | 8.6% | 70 (8) |

| (0.5%, 14.0%) | (0.6%, 14.8%) | (1.6%, 16.2%) | n = 115 | |

| P = 0.04, n = 109 | P = 0.03, n = 105 | P = 0.02, n = 136 | ||

| Urinary β2‐microglobulin (μg l−1) | 41.5% | 114.4% | 197.2% | 46 (35) |

| (−35.4%, 210.2%) | (−0.3%, 361.0%) | (32.4%, 566.8%) | n = 38 | |

| P = 0.4, n = 25 | P = 0.05, n = 34 | P = 0.01, n = 68 | ||

| Urinary KIM‐1 (ng ml−1) | −20.6% | 25.5% | 55.3% | 0.85 (0.66) |

| (−59.2%, 54.4%) | (−36.7%, 148.9%) | (−21.5%, 207.1%) | n = 35 | |

| P = 0.5, n = 24 | P = 0.5, n = 28 | P = 0.2, n = 57 | ||

| Urinary α‐GST * (μgl−1) | 77.8% | 29.0% | 280.6% | 9 (6) |

| (−0.19%, 0.70%) | (−0.62%, 0.16%) | (−0.55%, 0.22%) | n = 20 | |

| P = 0.2, n = 21 | P = 0.6, n = 21 | P = 0.004, n = 20 | ||

| Urinary NAG (IU l−1) | 16.1% | 52.4% | 8.6% | 5.92 (3.82) |

| (−14.8%, 2.1%) | (−7.2%, 9.8%) | (−6.1%, 11.1%) | n = 28 | |

| P = 0.5, n = 23 | P = 0.09, n = 26 | P = 0.7, n = 50 |

Urinary α‐GST not measured in additional samples for technical reasons.

Figure 2.

Average urinary kidney injury molecule‐1 concentrations (ng ml−1), with SD bars. SPC5001/placebo administration was on study days 1, 8 and 15. Averages include both scheduled and unscheduled samples, grouped by week. ( placebo,

placebo,  0.5 mg kg−1,

0.5 mg kg−1,  1.5 mg kg−1,

1.5 mg kg−1,  5mg kg−1)

5mg kg−1)

In the 5 mg kg–1 dosing group, the elevations in serum creatinine, β2‐microglobulin and α‐GST reached statistical significance (Table 2). It should be noted that the increases in β2‐microglobulin were isolated, transient and highly variable in timing between subjects and did not correlate with the observed changes in other tubular markers. No SPC5001‐related changes were observed in NAG (Table 2).

Injection site reactions

Injection site reactions (ISRs) developed dose‐dependently in 8/18 (44%) of the SPC5001‐treated subjects (0/6, 3/6 and 5/6 subjects in the 0.5, 1.5 and 5 mg kg–1 dosing groups, respectively). These skin reactions presented hours to days after the s.c. injections as painless erythema at the site of the injection (approximately 5 cm by 5 cm) with or without transient pruritus and/or swelling. Most skin lesions became clearly visible 1 week after the last SPC5001 administration. Subjects either had skin lesions at all three locations of the abdomen where SPC5001 had been administered, or they had no skin lesions at all. The ISRs did not worsen with each subsequent injection, and all skin lesions within a subject were of similar severity. The ISRs were of mild to moderate severity and caused significant discomfort to a subset of the volunteers. In one female, a maculopapular rash developed 1 week after the final dose. The patient was referred to a dermatologist who treated the patient with topical steroids resulting in resolution of the rash. In general, the ISRs persisted for several days to weeks and then diminished in intensity. However, in one female, subcutaneous skin atrophy developed, which was present at the final visit 2.5 months after dosing. Also, in six out of eight SPC5001‐treated subjects (three subjects from 1.5 mg kg–1 group and three subjects from 5 mg kg–1 group) skin hyperpigmentation was present at the last follow‐up visit at 2.5 months.

Other safety assessments

SPC5001 treatment did not result in clinically relevant changes in vital signs, ECG parameters, or coagulation, or in (trends to) increases in complement factors, cytokines or CRP, neither in subjects free of ISRs nor in subjects developing ISRs. Also, no clinically relevant changes in liver biochemistry parameters were observed, and none of the treated subjects had ultrasonographic signs of steatosis of the liver parenchyma at the last follow‐up visit. Adverse events that were observed more frequently in SPC5001‐treated subjects than in placebo‐treated subjects were mild headache (61 vs. 33%) and tiredness (56 vs. 17%), occurring not dose dependently throughout the complete study period with a higher incidence within the first 24 h after SPC5001/placebo administration, and generally spontaneously resolving within hours to days.

Pharmacokinetics

Maximal plasma concentrations were reached at 1.7 ± 0.5, 1.2 ± 0.4, and 2.5 ± 2.7 h post‐dose for 0.5, 1.5 and 5 mg kg–1 SPC5001, respectively (mean ± SD). The maximal plasma concentrations increased dose‐proportionally (281 ± 43, 757 ± 32, and 2424 ± 692 ng ml–1 for 0.5, 1.5 and 5 mg kg–1, respectively), while AUC(0,24 h) increased more than dose‐proportionally (1.78 ± 0.13, 5.01 ± 0.46 and 23.0 ± 3.8 μg ml–1 h for 0.5, 1.5 and 5 mg kg–1, respectively). The rate constants of the terminal phases describing the decline in SPC5001 plasma concentration were not formally calculated, but the half‐life of the final phase was estimated to be 7 days.

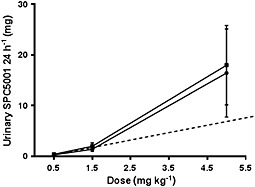

SPC5001 excreted in urine was determined in samples collected during 0–24 h after dosing on days 1 and 15. The total amount of SPC5001 in urine increased more than dose‐proportionally (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Average SPC5001 urinary excretion over 24 h (mg) after dosing, with SD bars. n = 6 subjects/dose level, except for 1.5 mg kg−1 (n = 5). ( day 1 (0–24 h),

day 1 (0–24 h),  day 15 (0–24 h))

day 15 (0–24 h))

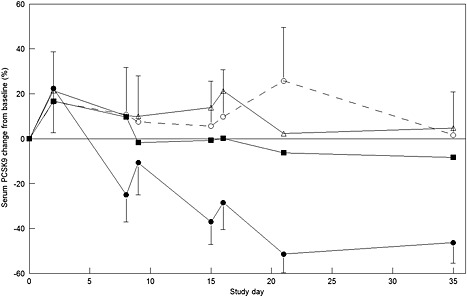

Pharmacodynamics

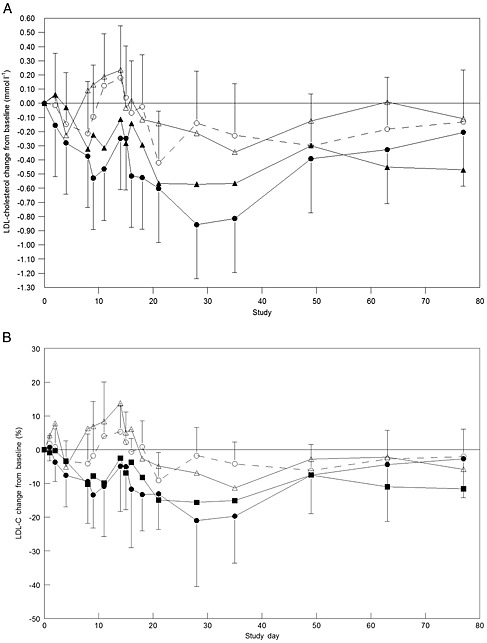

SPC5001 treatment resulted in a decrease in PCSK9 plasma concentration, reaching a level of significance when compared with placebo at the highest dose levels tested (Figure 4, Table 3). The maximal decrease in PCSK9 concentration was reached 1 week after the last SPC5001 administration (Figure 4; from 302 ± 80 ng ml–1 at baseline to 156 ± 85 ng ml–1 on day 21, at 5 mg kg–1 SPC5001), remaining decreased until at least the last measurement point on day 35 (Figure 4). SPC5001 also induced a dose‐dependent decrease in LDL‐C concentrations, with a maximal effect reached 2 weeks after the last SPC5001 administration (Figure 5, from 3.8 ± 0.8 mmol l–1 at baseline to 2.9 ± 1.1 mmol l–1 on day 29, for 5 mg kg–1 SPC5001). Although the observed effect was not significant for the full time profile (Table 3), the contrast between 5 mg kg–1 SPC5001 and placebo was statistically significant at day 28 (estimated difference − 0.72 mmol l–1, 95% confidence interval − 1.24, −0.16 mmol l–1; P < 0.01). LDL‐C concentrations returned to baseline 9 weeks after administration of the last SPC5001 dose. Furthermore, 5 mg kg–1 SPC5001 decreased apolipoprotein B (ApoB) (Table 3, P = 0.05 vs. placebo), with a maximal average decrease from baseline of approximately 15% (0.17 g l–1) observed 1 week after the last administration (data not shown), and increased apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA1) (Table 3, P = 0.04 vs. placebo), with a mean maximal average increase over baseline of 8% (0.13 g l–1) observed at study day 14 (data not shown). High‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL‐C), triglycerides (TG) and very low density lipoprotein cholesterol (VLDL‐C) concentrations were unaffected by SPC5001 treatment (Table 3).

Figure 4.

Average estimated PCSK9 concentrations (ng ml−1), expressed as % change from baseline with 95% confidence interval bars. ( placebo,

placebo,  0.5 mg kg−1,

0.5 mg kg−1,  1.5 mg kg−1,

1.5 mg kg−1,  5 mg kg−1)

5 mg kg−1)

Table 3.

Effects of SPC5001 treatment on lipid parameters. Estimated differences between active treatment and placebo, calculated over a period from baseline up to and including day 49, expressed as absolute change with corresponding unit or as percentage for log transformed parameters (PCSK9, HDL‐C, VLDL‐C and triglycerides), presented with 95% confidence interval and corresponding P value. Estimated difference for PCSK9 was calculated from baseline up to and including day 35

| 0.5 mg kg−1 SPC5001 vs. placebo | 1.5 mg kg−1 SPC5001 vs. placebo | 5 mg kg−1 SPC5001 vs. placebo | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCSK9 (%) | −2.5 | −15.0 | −49.0 |

| (−20.7, 20.0) | (−31.0, 4.7) | (−58.5, −37.2) | |

| P = 0.8 | P = 0.1 | P < 0.0001 | |

| ApoA1 (g l−1) | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.11 |

| (−0.07, 0.15) | (−0.09, 0.12) | (0.01, 0.21) | |

| P = 0.5 | P = 0.8 | P = 0.04 | |

| ApoB (g l−1) | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.09 |

| (−0.11, 0.07) | (−0.08, 0.09) | (−0.18, 0.00) | |

| P = 0.6 | P = 0.9 | P = 0.05 | |

| Total cholesterol (mmol l−1) | 0.24 | −0.22 | −0.19 |

| (−0.20, 0.69) | (−0.60, 0.17) | (−0.57, 0.20) | |

| P = 0.3 | P = 0.3 | P = 0.3 | |

| HDL‐C (%) | −6.9 (−15.0, 1.9) P = 0.1 | 0.7 (−7.5, 9.6) P = 0.9 | 2.8 (−5.5, 11.8) P = 0.5 |

| LDL‐C (mmol l−1) * | 0.06 | −0.18 | −0.36 |

| (−0.37, 0.50) | (−0.57, 0.21) | (−0.75, 0.03) | |

| P = 0.8 | P = 0.4 | P = 0.07 | |

| VLDL‐C (%) † | 34.7 | 2.9 | 22.8 |

| (−2.3, 85.6) | (−25.8, 42.5) | (−11.7, 70.8) | |

| P = 0.06 | P = 0.9 | P = 0.2 | |

| Triglycerides (%) | 34.5 | 3.2 | 23.0 |

| (−2.2, 84.6) | (−25.3, 42.5) | (−11.3, 70.6) | |

| P = 0.07 | P = 0.8 | P = 0.2 |

calculated with Friedewald formula: LDL‐C = (TC) − (HDL‐C) − (0.456*Triglycerides).

calculated as: (total cholesterol) − (HDL‐cholesterol) − (indirect LDL‐cholesterol)

Figure 5.

Average estimated LDL‐cholesterol concentrations in mmol l−1 (A) and in percentage (B), expressed as change from baseline with 95% confidence interval bars. (A)  placebo,

placebo,  0.5 mg kg−1,

0.5 mg kg−1,  1.5 mg kg−1,

1.5 mg kg−1,  5 mg kg−1; (B)

5 mg kg−1; (B)  placebo,

placebo,  0.5 mg kg−1,

0.5 mg kg−1,  1.5 mg kg−1,

1.5 mg kg−1,  5 mg kg−1

5 mg kg−1

Discussion

This study explored the pharmacokinetics and LDL‐C lowering effects of SPC5001, an LNA‐based PCSK9‐targeted antisense oligonucleotide, in healthy volunteers with moderately elevated LDL‐C concentrations. Proof‐of‐pharmacology for SPC5001 was achieved. SPC5001 administration resulted in a reduction of plasma PCSK9 and a lowering of LDL‐C and ApoB. However, the top dose (5 mg/kg) not only resulted in a maximal decrease in PCSK9 concentration of approximately 50% and a reduction in LDL‐C of maximally 25% compared with baseline, but also in renal tubular effects. It is unknown whether the more than dose‐proportional increase in SPC5001 plasma exposure (AUC0‐24hr) and urinary excretion, possibly representing a limitation in SPC5001's hepatic uptake/accumulation, relates to the observed nephrotoxicity.

Healthy cynomolgus monkeys dosed at similar or higher levels displayed the intended pharmacology (i.e. reduction in LDL‐C) but no indications of renal toxicity (Santaris Pharma A/S, unpublished observations). In these animals, SPC5001 dosing (loading dose of 20 mg kg−1, followed by four weekly doses of 5 mg kg−1) reduced hepatic PCSK9 messenger RNA and plasma PCSK9 protein concentrations by up to 85%, and circulating LDL‐C by up to 50% without affecting routine renal markers (urea and creatinine) 9. Also in a 13‐week toxicity study with a loading phase of up to 20 mg kg−1 per dose every 5th day for 16 days followed by a maintenance phase of 20 mg kg−1 week−1, neither clinical chemistry nor histopathology pointed to a tubular risk (Santaris Pharma A/S, unpublished GLP study report). However, interspecies differences in drug sensitivity are not unusual, hence the safety margins conventionally applied from animals to humans.

PCSK9 inhibition per se is unlikely to be the cause for the observed renal tubular toxicity observed in our study. Other PCSK9‐inhibiting modalities tested in clinical studies have not resulted in renal signals. Inhibition of PCSK9 synthesis by a single dose of silencing RNA was demonstrated to be a potentially safe and effective strategy, with a mean 70% reduction in circulating PCSK9 plasma protein (P < 0·0001) and a mean 40% reduction in LDL cholesterol from baseline relative to placebo (P < 0·0001) 14. Furthermore, no renal toxicity has been reported for plasma PCSK9‐directed antibodies, resulting in decreases in plasma PCSK9 concentrations up to 100% and reductions in LDL‐C between 60 and 80% in phase 1 trials 15, 16. Finally, there are no reports to our knowledge of functional renal changes in people with loss of function PCSK9 mutations 17.

The renal effects of SPC5001 included a transient increase in serum creatinine, with first onset after the last SPC5001 administration and peaking approximately 10 days after the final dose. This coincided with the appearance of urinary granular casts, and elevations of urinary kidney damage markers. One subject in the highest dose group developed acute tubular necrosis (ATN), which resolved spontaneously within 8 weeks. The observation of ATN is uncommon for unmodified oligodeoxynucleotides, 2′‐MOE modified and LNA modified oligonucleotides, which have all been successfully administered to humans without causing clinically meaningful renal functional changes 18, 19, 20. The target‐unrelated toxicity of individual oligonucleotides is diverse and probably driven by a range of factors including backbone and nucleoside chemistry, sequence and length. The mechanism behind renal toxicity associated with some oligonucleotides is currently unknown. It may relate to accumulation‐related degenerative effects on the proximal tubule although in animal models molecules that accumulate most are not necessarily the most toxic. For instance, miravirsen accumulated to a 8‐fold higher degree than SPC5001 in NHP kidney cortex and showed no renal toxicity in humans (Santaris Pharma A/S, Technical Reports and 19). Other factors such as individual susceptibility of the patient may be involved as well. It is important to note that adverse renal effects may also occur in AONs with chemistries other than LNA. There are reports on second generation AON‐induced proteinuria in patients with Duchenne's muscular dystrophy 21 and ATN in a metastatic cancer patient 22. It has also been previously stated in the literature that shorter oligonucleotides have lower plasma protein binding capability and, therefore, a larger proportion of the dose may pass the glomerulus and accumulate in the proximal tubular cells 23. However there is no relation, to our knowledge, between the rate of filtration and the level of tubular accumulation. Moreover, SPC5001 is a relatively short molecule (14‐mer) but shows a high binding (of >95%) to human serum albumin (Santaris Pharma A/S, internal data). In the current trial, only 1–3% of the dose was excreted in urine during the first 24 h after administration (approximately corresponding to the unbound fraction), which is low compared with a 24 h urinary dose recovery of 8–10% for miravirsen, a 15‐mer oligonucleotide that did not induce tubulotoxicity in early clinical trials 24, 25.

Because oligonucleotides accumulate in the proximal tubules to varying degrees 26, renal monitoring is performed for investigational compounds of this drug class. Not all clinical adverse events can be predicted pre‐clinically and it is therefore suggested that extensive renal safety monitoring for AONs should not be limited to routine measures such as serum creatinine and urinalysis, but should also include regular urine microscopy. In addition, measurement of the urinary excretion of specific tubular damage markers such as KIM‐1, β2‐microglobulin, α‐GST, and possibly NAG may also be informative. Thorough assessment of renal damage markers may allow early detection of impending renal damage and possibly provide mechanistic insight 27, which is crucial for the understanding of why some, but not all, oligonucleotides have been demonstrated to induce unintended renal effects. These proposed urinary biomarkers are not fully clinically validated, and while their use is encouraged, they may not yet be ready to support real‐time decision‐making.

Since the observed renal effects of SPC5001 in this clinical study, the stringency of renal safety screening of LNA oligonucleotides has increased. A recent rat‐based standard study including both routine and advanced biomarkers reproduced the tubulotoxicity of SPC5001 28. Further mechanistic studies are in progress to understand the factors causing this type of toxicity.

SPC5001 treatment dose‐dependently induced mild to moderate ISRs. The occurrence of ISR suggests that SPC5001, like other charged phosphorothioate oligonucleotides 29, has the potential to induce local (subcutaneous) inflammatory changes. In the present study, there was no evidence for systemic inflammation as indicated by the absence of elevations in C‐reactive protein and gamma globulins, circulating cytokines or complement activation (data not shown).

It has been reported that ISRs do occur in rodents and to a lesser extent in primates but also that animal models poorly predict this risk in humans 30. Subcutaneous administration of SPC5001 in preclinical models resulted in only minimal injection site effects, so the toxicology studies did not predict the magnitude of ISRs upon SPC5001 treatment in humans. However, the occurrence of AON‐induced ISRs in humans has been reported before. During the clinical development of mipomersen (2′‐MOE phosphorothioate AON), 84% of all mipomersen‐treated patients displayed ISRs compared with 33% of all placebo‐treated patients 31. Furthermore, PRO051 (a fully modified 2′‐O‐methyl phosphorothioate AON) administered to patients with Duchenne's muscular dystrophy resulted in erythema and inflammation at the injection site in 9 out of 12 treated patients 21. This shows that phosphorothioate AONs have the potential to induce injection site reactions. It is currently unknown how sequence and structure of AON compounds relates to the nature of skin lesions and dose, concentration and volume are factors that may modulate these effects. However, a wide range of ISR‐inducing potencies has been observed across development compounds (Santaris Pharma A/S, unpublished observations). The increased potency and duration of action of next‐generation antisense oligonucleotides (and related less frequent dosing regimens and smaller injection volumes) may reduce the risk of ISR development 32, 33, 34. Data need to be generated more systematically and for that purpose it is essential that injection site reactions are documented in more detail, preferably following a standardized (AON‐specific) scoring system. Furthermore, the underlying pathophysiology of ISRs remains poorly understood.

In conclusion, SPC5001 administered to healthy volunteers with mildly elevated LDL‐C resulted in dose‐dependent reductions in LDL‐C and PCSK9. However, subcutaneous injections of SPC5001 were associated with ISRs and transient renal tubular toxicity at 5 mg/kg. It is now recognized that within the LNA chemical class, these toxicities vary greatly across compound sequences and further screens have been or are being phased in to reduce those risks at the discovery stage 28. The ultimate goal is to obtain insights into the molecular mechanisms behind the side effects of compounds such as SPC5001, with a view to improve the quality of compound libraries. In the same spirit, sensitive and relevant monitoring strategies for renal toxicity should be implemented for future oligonucleotide therapies.

Competing Interests

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare this clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT01350960) was sponsored by Santaris Pharma A/S with no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. MH, YT, AL, RP, ML, KD and HØ were employees of previously Santaris Pharma A/S, now Roche Pharmaceutical Research and Early Development, Roche Innovation Center Copenhagen, Hørsholm, Denmark. AL had financial relationships with miRagen Therapeutics Inc, Boulder, Colorado, USA and Avidity NanoMedicines, La Jolla, California, USA in the previous 3 years. The drug was supplied by KLIFO A/S, Copenhagen Science Park Symbion, Fruebjergvej 3, 2100 Copenhagen, Denmark.

Contributors

EvP performed research, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. MM designed research, analyzed data and reviewed the text. M.H. designed research, analyzed data and reviewed the text. YT designed research, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. AL designed research, analyzed data and reviewed the text. RP analyzed data and reviewed the text. KDE reviewed the text. ML designed research and reviewed the text. HØ designed research and reviewed the text. AC designed research, analyzed data and reviewed the text. JB performed research, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript.

We would like to thank Professor J.J.P. Kastelein (Professor of Medicine and chairman of the Department of Vascular Medicine at the Academic Medical Center (AMC) of the University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands, where he holds the Strategic Chair of Genetics of Cardiovascular Disease) for his role as consultant/adviser in designing the study.

van Poelgeest, E. P. , Hodges, M. R. , Moerland, M. , Tessier, Y. , Levin, A. A. , Persson, R. , Lindholm, M. W. , Dumong Erichsen, K. , Ørum, H. , Cohen, A. F. , and Burggraaf, J. (2015) Antisense‐mediated reduction of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9): a first‐in‐human randomized, placebo‐controlled trial. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 80: 1350–1361. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12738.

References

- 1. Silva MA, Swanson AC, Gandhi PJ, Tataronis GR. Statin‐related adverse events: a meta‐analysis. Clin Ther 2006; 28: 26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goldstein JL, Brown MS. The LDL receptor. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2009; 29: 431–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nassoury N, Blasiole DA, Tebon OA, Benjannet S, Hamelin J, Poupon V, McPherson PS, Attie AD, Prat A, Seidah NG. The cellular trafficking of the secretory proprotein convertase PCSK9 and its dependence on the LDLR. Traffic 2007; 8: 718–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Abifadel M, Varret M, Rabes JP, Allard D, Ouguerram K, Devillers M, Cruaud C, Benjannet S, Wickham L, Erlich D, Derre A, Villeger L, Farnier M, Beucler I, Bruckert E, Chambaz J, Chanu B, Lecerf JM, Luc G, Moulin P, Weissenbach J, Prat A, Krempf M, Junien C, Seidah NG, Boileau C. Mutations in PCSK9 cause autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia. Nat Genet 2003; 34: 154–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tibolla G, Norata GD, Artali R, Meneghetti F, Catapano AL. Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9): from structure‐function relation to therapeutic inhibition. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2011; 21: 835–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cohen JC, Boerwinkle E, Mosley TH Jr, Hobbs HH. Sequence variations in PCSK9, low LDL, and protection against coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 1264–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cohen J, Pertsemlidis A, Kotowski IK, Graham R, Garcia CK, Hobbs HH. Low LDL cholesterol in individuals of African descent resulting from frequent nonsense mutations in PCSK9. Nat Genet 2005; 37: 161–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gupta N, Fisker N, Asselin MC, Lindholm M, Rosenbohm C, Orum H, Elmen J, Seidah NG, Straarup EM. A locked nucleic acid antisense oligonucleotide (LNA) silences PCSK9 and enhances LDLR expression in vitro and in vivo . PLoS One 2010; 5: e10682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lindholm MW, Elmen J, Fisker N, Hansen HF, Persson R, Moller MR, Rosenbohm C, Orum H, Straarup EM, Koch T. PCSK9 LNA antisense oligonucleotides induce sustained reduction of LDL cholesterol in nonhuman primates. Mol Ther 2012; 20: 376–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Navarese EP, Kolodziejczak M, Schulze V, Gurbel PA, Tantry U, Lin Y, Brockmeyer M, Kandzari DE, Kubica JM, D'Agostino RB Sr, Kubica J, Volpe M, Agewall S, Kereiakes DJ, Kelm M. Effects of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 antibodies in adults with hypercholesterolemia: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Ann Intern Med 2015; 163: 40–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Robinson JG, Farnier M, Krempf M, Bergeron J, Luc G, Averna M, Stroes ES, Langslet G, Raal FJ, El SM, Koren MJ, Lepor NE, Lorenzato C, Pordy R, Chaudhari U, Kastelein JJ. Efficacy and safety of alirocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1489–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Veedu RN, Wengel J. Locked nucleic acid as a novel class of therapeutic agents. RNA Biol 2009; 6: 321–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van Poelgeest EP, Swart RM, Betjes MG, Moerland M, Weening JJ, Tessier Y, Hodges MR, Levin AA, Burggraaf J. Acute kidney injury during therapy with an antisense oligonucleotide directed against PCSK9. Am J Kidney Dis 2013; 62: 796–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fitzgerald K, Frank‐Kamenetsky M, Shulga‐Morskaya S, Liebow A, Bettencourt BR, Sutherland JE, Hutabarat RM, Clausen VA, Karsten V, Cehelsky J, Nochur SV, Kotelianski V, Horton J, Mant T, Chiesa J, Ritter J, Munisamy M, Vaishnaw AK, Gollob JA, Simon A. Effect of an RNA interference drug on the synthesis of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) and the concentration of serum LDL cholesterol in healthy volunteers: a randomised, single‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 1 trial. Lancet 2014; 383: 60–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dias CS, Shaywitz AJ, Wasserman SM, Smith BP, Gao B, Stolman DS, Crispino CP, Smirnakis KV, Emery MG, Colbert A, Gibbs JP, Retter MW, Cooke BP, Uy ST, Matson M, Stein EA. Effects of AMG 145 on low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol levels: results from two randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, ascending‐dose phase 1 studies in healthy volunteers and hypercholesterolemic subjects on statins. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 60: 1888–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stein EA, Mellis S, Yancopoulos GD, Stahl N, Logan D, Smith WB, Lisbon E, Gutierrez M, Webb C, Wu R, Du Y, Kranz T, Gasparino E, Swergold GD. Effect of a monoclonal antibody to PCSK9 on LDL cholesterol. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 1108–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhao Z, Tuakli‐Wosornu Y, Lagace TA, Kinch L, Grishin NV, Horton JD, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Molecular characterization of loss‐of‐function mutations in PCSK9 and identification of a compound heterozygote. Am J Hum Genet 2006; 79: 514–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Crooke S. Antisense Drug Technology: Principles, Strategies, and Applications, 2nd edn Boca Raton Florida: CRC Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Janssen HL, Reesink HW, Lawitz EJ, Zeuzem S, Rodriguez‐Torres M, Patel K, van der Meer AJ, Patick AK, Chen A, Zhou Y, Persson R, King BD, Kauppinen S, Levin AA, Hodges MR. Treatment of HCV infection by targeting microRNA. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 1685‐1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Raal FJ, Santos RD, Blom DJ, Marais AD, Charng MJ, Cromwell WC, Lachmann RH, Gaudet D, Tan JL, Chasan‐Taber S, Tribble DL, Flaim JD, Crooke ST. Mipomersen, an apolipoprotein B synthesis inhibitor, for lowering of LDL cholesterol concentrations in patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet 2010; 375: 998–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Goemans NM, Tulinius M, van den Akker JT, Burm BE, Ekhart PF, Heuvelmans N, Holling T, Janson AA, Platenburg GJ, Sipkens JA, Sitsen JM, Aartsma‐Rus A, van Ommen GJ, Buyse G, Darin N, Verschuuren JJ, Campion GV, de Kimpe SJ, van Deutekom JC. Systemic administration of PRO051 in Duchenne's muscular dystrophy. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 1513–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Herrington WG, Talbot DC, Lahn MM, Brandt JT, Callies S, Nagle R, Winearls CG, Roberts IS. Association of long‐term administration of the survivin mRNA‐targeted antisense oligonucleotide LY2181308 with reversible kidney injury in a patient with metastatic melanoma. Am J Kidney Dis 2011; 57: 300–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Laxton C, Brady K, Moschos S, Turnpenny P, Rawal J, Pryde DC, Sidders B, Corbau R, Pickford C, Murray EJ. Selection, optimization, and pharmacokinetic properties of a novel, potent antiviral locked nucleic acid‐based antisense oligomer targeting hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55: 3105–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hildebrandt‐Eriksen ES, Aarup V, Persson R, Hansen HF, Munk ME, Orum H. A locked nucleic acid oligonucleotide targeting microRNA 122 is well‐tolerated in cynomolgus monkeys. Nucleic Acid Ther 2012; 22: 152–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. van der Ree MH, van der Meer AJ, de Bruijne J, Maan R, van Vliet A, Welzel TM, Zeuzem S, Lawitz EJ, Rodriguez‐Torres M, Kupcova V, Wiercinska‐Drapalo A, Hodges MR, Janssen HL, Reesink HW. Long‐term safety and efficacy of microRNA‐targeted therapy in chronic hepatitis C patients. Antiviral Res 2014; 111: 53–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bennett CF, Swayze EE. RNA targeting therapeutics: molecular mechanisms of antisense oligonucleotides as a therapeutic platform. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2010; 50: 259–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Waring WS, Moonie A. Earlier recognition of nephrotoxicity using novel biomarkers of acute kidney injury. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2011; 49: 720–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lindholm MW. LNA oligonucleotide in vivo renal screening v2.0 (Poster), DIA/FDA meeting on oligonucleotide therapeutics, Washington, September 2013.

- 29. Hair P, Cameron F, McKeage K. Mipomersen sodium: first global approval. Drugs 2013; 73: 487–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Engelhardt JA. Predictivity of animal studies for human injection site reactions with parenteral drug products. Exp Toxicol Pathol 2008; 60: 323–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.FDA Briefing Document NDA 203568 Mipomersen Sodium Injection 200 mg/mL (2012). 2015.

- 32. Frazier KS. Antisense oligonucleotide therapies: the promise and the challenges from a toxicologic pathologist's perspective. Toxicol Pathol 2015; 43: 78–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nair JK, Willoughby JL, Chan A, Charisse K, Alam MR, Wang Q, Hoekstra M, Kandasamy P, Kel'in AV, Milstein S, Taneja N, O'Shea J, Shaikh S, Zhang L, van der Sluis RJ, Jung ME, Akinc A, Hutabarat R, Kuchimanchi S, Fitzgerald K, Zimmermann T, van Berkel TJ, Maier MA, Rajeev KG, Manoharan M. Multivalent N‐acetylgalactosamine‐conjugated siRNA localizes in hepatocytes and elicits robust RNAi‐mediated gene silencing. J Am Chem Soc 2014; 136: 16958–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Prakash TP, Graham MJ, Yu J, Carty R, Low A, Chappell A, Schmidt K, Zhao C, Aghajan M, Murray HF, Riney S, Booten SL, Murray SF, Gaus H, Crosby J, Lima WF, Guo S, Monia BP, Swayze EE, Seth PP. Targeted delivery of antisense oligonucleotides to hepatocytes using triantennary N‐acetyl galactosamine improves potency 10‐fold in mice. Nucleic Acids Res 2014; 42: 8796–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]