Abstract

Removal of introns from pre‐mRNA precursors (pre‐mRNA splicing) is a necessary step for the expression of most genes in multicellular organisms, and alternative patterns of intron removal diversify and regulate the output of genomic information. Mutation or natural variation in pre‐mRNA sequences, as well as in spliceosomal components and regulatory factors, has been implicated in the etiology and progression of numerous pathologies. These range from monogenic to multifactorial genetic diseases, including metabolic syndromes, muscular dystrophies, neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases, and cancer. Understanding the molecular mechanisms associated with splicing‐related pathologies can provide key insights into the normal function and physiological context of the complex splicing machinery and establish sound basis for novel therapeutic approaches.

Keywords: alternative splicing, disease, mutation, RNA, spliceosome

Subject Categories: Molecular Biology of Disease, RNA Biology

Glossary

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- ALS

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- AML

Acute myeloid leukemia

- APC2

Adenomatosis polyposis coli 2

- APP

Amyloid precursor protein

- AS

Alternative splicing

- ASO

Antisense oligonucleotide

- BPS

Branch point sequence

- BRAF

V‐Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B

- BRR2

Bad response to refrigeration 2

- CFTR

Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- CLL

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- CLCN1

Chloride channel, voltage‐sensitive 1

- CMML

Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia

- CNBP

CCHC‐type zinc finger, nucleic acid‐binding protein

- CUG‐BP1

CUG‐binding protein 1

- DM

Myotonic dystrophy

- DMD

Duchenne muscular dystrophy

- DMPK

Dystrophia myotonica‐protein kinase

- EFTUD2

Elongation factor Tu GTP binding domain containing 2

- ESE

Exonic splicing enhancer

- ESS

Exonic splicing silencer

- ExSpeU1

Exon specific U1 snRNA

- FD

Familial dysautonomia

- FTDP‐17

Frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17

- FTD

Frontotemporal dementia

- FTLD

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration

- FUS

Fused in sarcoma

- GOF

Gain of function

- HD

Huntington's disease

- hMpn1/Usb1

Mutated in poikiloderma with neutropenia protein 1/U6 snRNA biogenesis 1

- hnRNP

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein

- Htt

Hungtingtin

- HuR

Hu antigen R

- IKBKAP

Inhibitor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells, kinase complex‐associated protein

- ISE

Intronic splicing enhancer

- ISS

Intronic splicing silencer

- LOF

Loss of function

- MAPT

Microtubule associated protein Tau

- MBNL

Muscleblind

- MDS

Myelodysplastic syndrome

- MFDM

Mandibulofacial dysostosis with microcephaly

- MOPD1

Microcephalic osteodysplastic primordial dwarfism type 1

- Myc

V‐myc myelocytomatosis viral oncogene &!#6;homolog

- NTC

NineTeen Complex

- NOVA

Neuro‐oncological ventral antigen

- ORF

Open reading frame

- PAP‐1

Pim‐1‐associated protein

- PKC

Protein kinase C

- PN

Poikiloderma with neutropenia

- PRP40

Pre‐mRNA processing factor 40

- PRPF

Pre‐mRNA processing factor

- PTB

Polypyrimidine tract‐binding protein

- PTM

Pre‐trans‐splicing molecule

- RARS

Refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts

- RAS

Rat sarcoma gene

- RBFOX

RNA‐binding protein Fox

- RBM5

RNA‐binding motif protein 5

- RNA‐Seq

RNA sequencing

- Ron

Recepteur d'origine nantais oncogene

- RP

Retinitis pigmentosa

- S6K1

Ribosomal protein S6 kinase I

- Sam68

Src‐associated in mitosis 68 kDa protein

- SAV

Splice‐altering variants

- SF1/BBP

Splicing factor 1/branch point binding protein

- SLE

Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Sm

Protein components of many snRNPs, named in honor of S. Smith, a SLE patient

- SMA

Spinal muscular atrophy

- SMART

Spliceosome‐mediated RNA trans‐splicing

- SMN1

Survival motor neuron 1

- snRNP

Small nuclear ribonucleoprotein

- SNRNP200

Small nuclear ribonucleoprotein 200 kDa (U5)

- SNW1

SNW domain containing 1

- SR proteins

Serine/arginine proteins

- SS

Splice site

- SSO

Splice‐switching oligonucleotide

- TARP

Talipes equinovarus, Atrial septal defects, Robin sequence, and Persistent left superior vena cava

- TDP‐43

Transactive responsive DNA‐binding protein 43 kDa

- TIA‐1/TIAR

T‐cell‐restricted intracellular antigen‐1/TIA‐1‐related protein

- U2AF

U2 auxiliary factor

- UBL5

Ubiquitin‐like protein 5

- U snRNP

Uridine‐rich small nuclear ribonucleoprotein

- ZNF9

Zinc finger protein 9

- ZRSR2

Zinc finger (CCCH type), RNA‐binding motif, and serine/arginine‐rich 2

Introduction

The central dogma of Molecular Biology emerged originally as a collinear view of gene expression, in which the information flows from DNA to protein through messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules. The last decades of research have considerably expanded this paradigm by showing the multiplicity of transcripts that can be generated from a single DNA locus through the use of alternative promoters, termination sites, and through alternative splicing of introns, intervening sequences present in primary transcripts that need to be removed to generate translatable mRNAs. Furthermore, intertwined links between transcriptional and posttranscriptional steps in the gene expression pathway, both in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm, not only facilitate coupling between these processes but also expand their regulatory possibilities, particularly in higher eukaryotes 1.

Pre‐mRNA splicing requires precise recognition of cis‐acting sequences on the pre‐mRNA by spliceosomal components and additional RNA‐binding factors, and involves a vast network of RNA–RNA, RNA–protein, and protein–protein interactions. The realization that at least 95% of human genes produce multiple spliced RNA species via alternative exon usage has revealed the prevalence of this additional layer of gene expression regulation 2. Indeed, alternative splicing (AS) enables individual genes to increase their coding capability and to generate a set of structurally and functionally distinct protein isoforms. The main types of AS are “cassette” exon skipping, alternative 5′ and 3′ splice site selection, alternatively retained introns, and mutually exclusive exons. Interestingly, the frequency of AS varies with species complexity and cell type, during development or upon cellular differentiation, thereby participating in the fine tuning of a gene signature both temporally and spatially 3, 4.

Mis‐regulation of splicing has been long known to be related to an increasing number of human pathologies, including genetic diseases, neurodegenerative disorders, and cancer. Alterations in pre‐mRNA splicing can either act as drivers of disease etiology or act as modifiers that sensitize individuals to disease susceptibility and severity. Recent excellent reviews have covered multiple aspects of this topic 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11. In this review, we provide a general overview of the function of the spliceosome and the combinatorial rules governing the splicing code. Our focus will be on splicing aberrations in various pathological contexts and how understanding the underlying mechanistic principles can set the stage for the development of novel therapeutic approaches and at the same time shed light on the function and physiology of splicing itself.

Basics of the pre‐mRNA‐splicing process

Successful completion of the splicing reaction and deployment of its physiological function require both fidelity and flexibility. First, the discrimination between correct and incorrect splice sites is achieved through systematic, multistage proofreading of the sequences by different factors. Second, splicing commitment is subject to an elaborated and dynamic crosstalk between splicing regulatory factors in order to enforce or to repress splice site selection (for recent reviews: 12, 13, 14, 15, 16).

Exon definition & the spliceosome assembly pathway

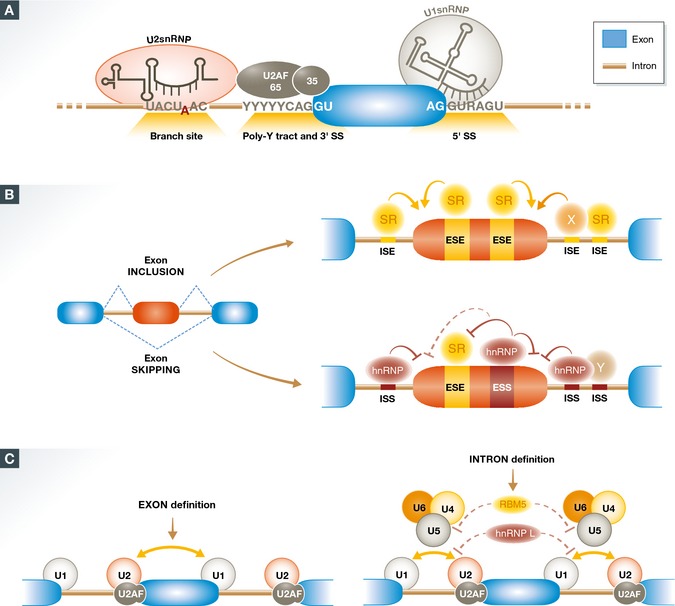

Intron removal is orchestrated by the multi‐megadalton macromolecular ribonucleoprotein complex known as the spliceosome, which is composed of five small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (U1, U2, U4/U6, U5 snRNP) and more than 200 snRNP‐ and non‐snRNP‐associated proteins 14. The definition of an intron relies on four consensus elements: the exon/intron junctions at the 5′ and 3′ end of the intron—the 5′ and 3′ splice sites (SS)—, the branch point sequence (BPS) located upstream of the 3′ SS, and the polypyrimidine tract located between the BPS and the 3′ SS (Fig 1A). The BPS adenosine plays a crucial role in splicing catalysis, by forming a 2′–5′ phosphodiester bond with the 5′ end of the intron after the first step of the reaction. The 5′ SS and the region surrounding the BPS are recognized through base‐pairing interactions with U1 and U2 snRNAs, respectively. Additional regulatory sequences within introns and exons contribute to splice site recognition by the core splicing machinery (Fig 1B and see below). In vertebrates, given the longer length of introns compared with exons, splice sites flanking an internal exon communicate with each other to help in initial exon definition 17, and subsequently engage in interactions across the intron to allow intron removal and exon inclusion (Fig 1C). Modulation of splice site pairing during exon and intron definition can be the target of regulators 18, 19, 20 (Fig 1C).

Figure 1. Mechanisms of splice site recognition and exon definition.

(A) Splicing complex assembly is initiated by consensus sequence elements located at the exon (blue)/intron (brown) boundaries. Recognition of the 5′ SS by U1 snRNP involves base‐pairing interactions between the 5′ end of U1 snRNA. Recognition of the 3′ SS region involves binding of the U2AF65/35 heterodimer to the polypyrimidine tract (Poly‐Y tract) and conserved 3′ SS, which facilitates recruitment of U2 snRNP to the branch site, involving base‐pairing interactions between U2 snRNA and nucleotides flanking the branch point adenosine. (B) Exon definition modulated by exonic and intronic sequence elements, which can promote (ESE & ISE, in orange) or suppress (ESS & ISS, in dark red) splice site recognition. A classic model involves recognition of splicing enhancers by proteins of the SR family and recognition of splicing silencers by hnRNP proteins. However, proteins of these and other families can promote or inhibit splicing depending upon the location of their binding sites relative to the splice sites and other regulatory sequences. A complex combinatorial interplay between regulatory elements and their cognate factors determines exon definition and regulation. (C) A switch from stabilizing interactions between factors recognizing 3′ and 5′ SS across exons (exon definition) to splice site pairing (intron definition) and tri‐snRNP assembly occurs in vertebrate internal exons and can be targeted by regulatory factors like hnRNP L or RBM5.

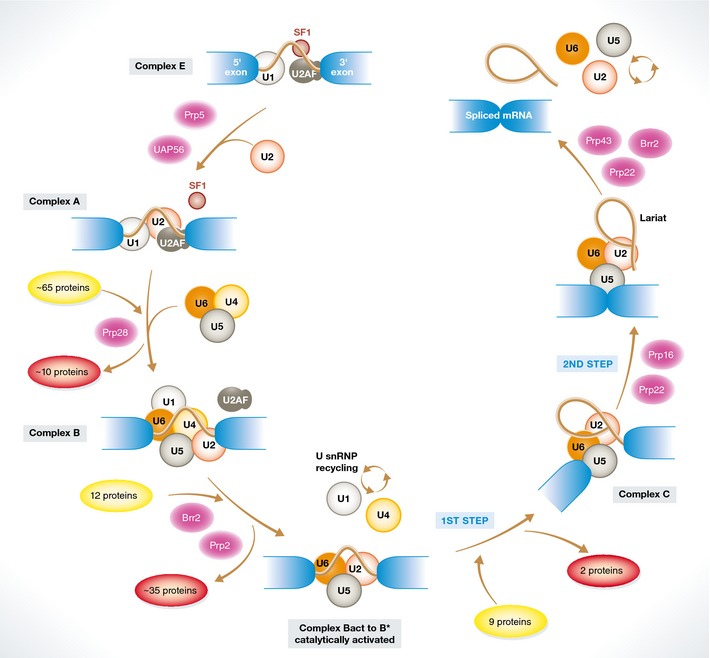

Assembly of spliceosomal complexes onto pre‐mRNA follows a stepwise choreography and is supported by at least eight DExD/H‐type RNA‐dependent ATPases/helicases whose function is either to remodel snRNP composition or to proofread specific transitions along the assembly cycle. The initial step begins with the recognition of the 5′ SS by U1 snRNP and the cooperative binding of the splicing factor 1 (SF1) and of the heterodimer U2AF65/U2AF35 to the BPS region, polypyrimidine tract and 3′ AG, respectively, generating complex E (Fig 2). These molecular interactions then trigger the ATP‐dependent recruitment of the U2 snRNP to the BPS region through base‐pairing interactions that bulge out the BPS adenosine. U2 snRNP assembly is also assisted by U2 snRNP‐associated proteins engaging in RNA–protein interactions with sequences around the BPS region and in protein–protein interactions (e.g., between the SF3B1 protein and U2AF65). Subsequent to complex A formation, the pre‐assembled U4‐U6‐U5 tri‐snRNP joins the pre‐spliceosome complex to establish complex B. The enzymatic activation of the machinery takes place at this stage through a series of conformational and massive compositional rearrangements (including displacement of U1 and U4 snRNP) to successively form the catalytically active complex B (Bact, B*) and complex C, which host, respectively, the 1st and 2nd trans‐esterification reactions of the splicing reaction 14, 21 (Fig 2).

Figure 2. The spliceosome assembly pathway.

Initial recognition of the 5′ SS by U1 snRNP and of the 3′ SS region by SF1 (branch point binding protein) and U2AF (complex E) is followed by the ATP‐dependent recruitment of U2 snRNP to the branch point region (complex A), concomitant with displacement of SF1. Binding of the U4/5/6 tri‐snRNP and the protein‐only NineTeen Complex (NTC) leads to formation of complex B, involving also the displacement of proteins present in complex A. Extensive remodeling of complex B, including the destabilization/displacement of U1 and U4 snRNPs, leads to a catalytically active complex (Bact), which upon further conformational rearrangements and changes in protein composition catalyzes the first step of the splicing reaction, leading to the formation of a lariat intermediate containing a 2′‐5′ phosphodiester bond (complex C). An additional conformational switch leads to the second catalytic step, rendering the spliced product and the intron lariat. Upon release of the products, the lariat intron is linearized and degraded and the snRNPs recycled for another round of assembly and catalysis in other introns. Proteins of the ATP‐dependent DEAH/X helicase family (in magenta) are key to promote the multiple conformational transitions, characterized by extensive rearrangements of RNA:RNA interactions involving snRNA:snRNA and snRNA:pre‐mRNA contacts.

From constitutive to alternative splicing

The core splicing sequences in higher eukaryotes are often variable and contain too little information to unambiguously define SS. Additional sequences in the pre‐mRNA modulate SS recognition and are referred to as exonic or intronic splicing enhancers (ESE or ISE) or silencers (ISS or ESS). These sequence elements are recognized by trans‐acting splicing factors that balance splice site selection and alternative splicing decisions (Fig 1B). Trans‐acting factors include the serine/arginine‐rich domain‐containing (SR) protein and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) families, which display cooperative or antagonistic effects on the recruitment of the core splicing machinery, typically at early stages of spliceosome formation 22. In addition, several tissue‐restricted regulators have been identified, including the neuronal‐specific determinants neuro‐oncological ventral antigen (NOVA), RNA‐binding Fox (RBFOX) or muscleblind (MBNL). Two recurrent themes are that the same factors can act as activators or repressors depending on the position of their binding sites relative to the regulated SS and that their precise activity depends on the context of other cognate sites for other regulatory factors with which they can establish cooperative or antagonistic interactions 23. This leads to a complex interplay of regulatory sequences, positional effects, and trans‐acting factor interactions that establish the functional framework of a splicing code 23, 24, 25. In addition, variations in the levels or activity of core splicing factors, even those acting late in the spliceosome assembly pathway, can also modulate SS choice 18, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30. Furthermore, an increasing number of studies revealed that splicing regulation is also subjected to complex interaction with the transcription and chromatin machineries. Indeed, changes in the kinetics of RNA polymerase II elongation can markedly affect SS selection by influencing the ability of splicing regulators to bind to nascent mRNAs 31, 32. In addition, histone marks and nucleosome positioning are also key features that participate in splicing reactions by helping the recruitment of splicing regulators and collaborating in exon definition, respectively 13, 25, 33, 34. Finally, signal transduction cascades represent another regulatory level through the modulation of posttranslational modifications of splicing regulators, which may modify their interactions, activities, and localization 23, 35.

Alterations of splicing in pathological conditions

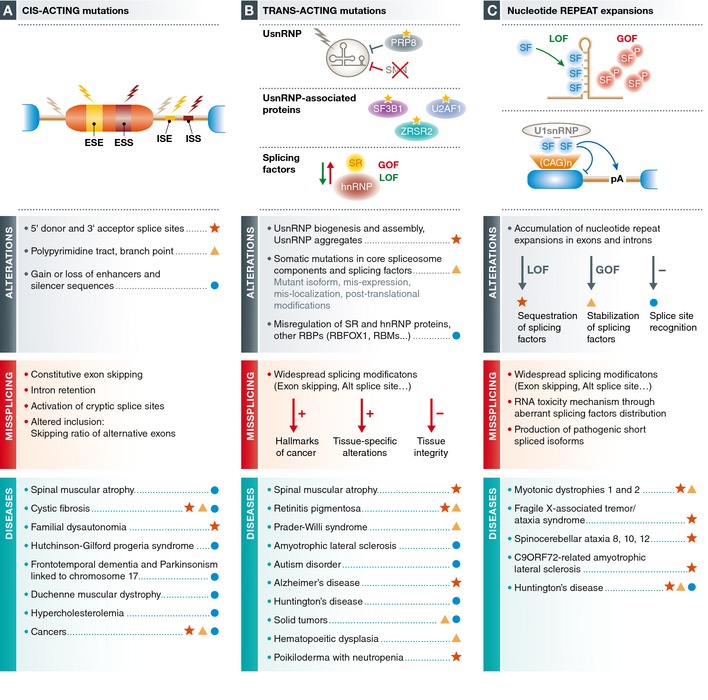

There is growing evidence from both human genetics and genomewide studies that splicing control can impact a variety of pathologies at three levels (Fig 3): (i) Mutations or genetic variants that affect cis‐acting sequences by decreasing the specificity or fidelity of SS selection or activating cryptic SS that are normally not used. These alterations impinge on single genes. (ii) Functional alterations in trans‐acting splicing factors, including core spliceosomal components and regulatory factors. Such perturbations potentially modify the expression of multiple RNA targets. (iii) Stoichiometric imbalance of splicing factors following their sequestration in repetitive elements. Such squelching mechanism brings about widespread gene expression changes. While abundant examples of such pathogenic mechanisms exist, it is expected that further combined experimental and computational approaches will greatly expand the repertoire—and possibly the categories of mechanisms—of mutations that determine predisposition, onset and/or progression of pathologies, opening novel opportunities for diagnosis, and translational research.

Figure 3. Spectrum of pathologies associated with splicing defects.

Broadly classified as mutations in sequence elements (A), alterations in splicing factors (B) and titration/signaling effects of nucleotide repeat expansions (C), the nature of various molecular alterations and their effects on splicing are described for various pathologies associated with splicing defects.

Cis‐acting mutations: breaking the splicing code

Genetic variation within splice site and regulatory sequences frequently causes aberrant splicing in human hereditary diseases and cancer. Single nucleotide substitutions affecting the 5′ or the 3′ SS are the most common splicing mutations, resulting either in exon skipping, activation of a cryptic SS, or to a lesser extent in intron retention. Similarly, intronic mutations and exonic variations (e.g., missense, nonsense, or even otherwise silent mutations) can often trigger splicing perturbations through a loss and/or a gain of enhancers/silencers. This is illustrated by the analysis of the mutational landscape of the Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (CFTR) gene related to cystic fibrosis 36, or of the neurofibromatosis gene, where 50% of the disease‐causing mutations lead to splicing defects 37. These alterations can occur in both constitutive and alternative exons and consequently generate aberrant transcripts that miss a constitutive exon or result in changes in the ratio between spliced isoforms (Fig 3A).

According to the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD release 2014.4), mutations that disrupt normal splicing have been estimated to account for up to a third of all disease‐causing mutations 38, 39, 40, 41. In silico tools have been developed for predicting the penetrance associated with de novo mutations and the molecular consequences for disease formation 42. These efforts should be complemented with predictions of the impact of frequent intronic regulatory sequences as well as exonic silent mutations (or even missense mutations) that affect splicing outcomes. In fact, synonymous variants have already been demonstrated to contribute to human diseases and be particularly prevalent modulators of exon usage 36, 43, 44, 45. Consistent with the observation that cancer‐related genes may harbor a greater susceptibility toward aberrant splicing 46, recurrent synonymous mutations in ESE and ESS have been identified for a subset of important oncogenes, representing an extra mechanism for oncogene activation. More globally, half of synonymous drivers is estimated to alter splicing 44, further emphasizing the importance of splicing in cancer biology.

The MutPred Splice algorithm aims to determine functional relationships between exonic variants and mis‐splicing in inherited diseases and cancer 47. The results indicate that in inherited disease, loss of natural splice sites represents the principal category of splice‐altering variants (SAV), whereas ESE loss and/or ESS gain leading to exon skipping is more frequent in cancer 47. More recently, Xiong, Frey, and colleagues assessed the effects of 650,000 single nucleotide intronic and exonic variants using a machine‐learning computational pipeline that uncovered an extensive impact of mutation‐associated splicing alterations. Their results estimate that intronic mutations alter splicing nine times more frequently than other common variants and that disease‐associated missense exonic mutations are five times more likely to interfere with splicing than non‐disease‐associated variants 45, further illustrating the potential impact of splicing alterations on human pathologies. This approach led to the identification of splicing alterations with potential roles in autism and provided an explanation for the penetrance of synonymous mutations in colorectal cancer 45.

The following examples illustrate how disease‐causing mutations can be tightly linked to multiple aspects of splice site recognition and, in fact, help to illustrate the delicate balance of sequence signals and interactions that tune splice site choice and can potentially inform therapeutic approaches (see also Figs 3 and 4 and section on therapies).

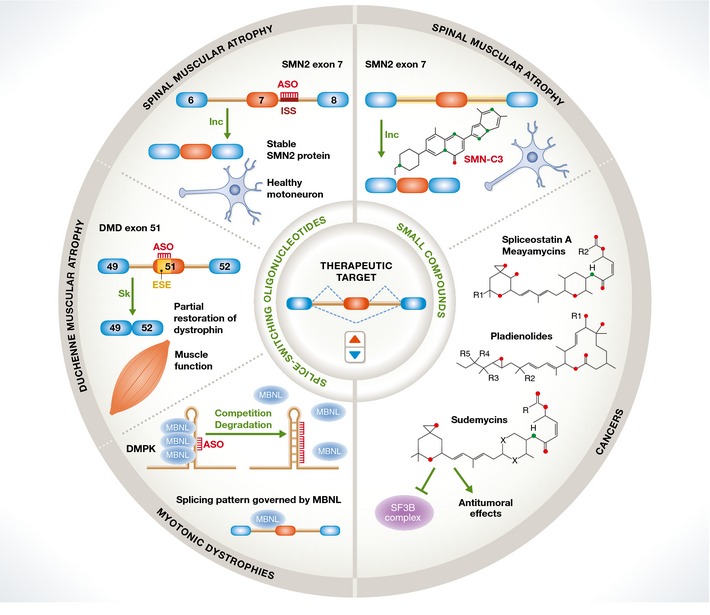

Figure 4. Summary of therapeutic approaches based upon splicing modulation.

Two main strategies are outlined. Splice‐switching antisense oligonucleotides target splice sites or splicing regulatory sequences to prevent the binding of cognate factors to modulate splice site selection. Examples include blocking of an ISS element that promotes exon 7 inclusion in the SMN2 gene, leading to restoring SMN protein expression and motoneuron function in SMA; induction of skipping of a mutation‐containing exon in the DMD gene, leading to in‐frame deletion of a nonessential part of the dystrophin protein and restoration of muscle function; prevention of sequestration of the MBNL splicing regulator in CUG repeat expansions in DMPK transcripts, leading to restoration of abnormal splicing patterns in DM. Small molecules, some of them targeting core splicing components like SF3B, modulate alternative splicing of cell cycle control genes and display anti‐tumoral properties. Other drugs can induce SMN2 exon 7 inclusion and therefore raise hope as oral treatments for SMA.

The vast majority of patients with familial dysautonomia (FD) contain a point mutation at the sixth position of intron 20 of the IKBKAP gene, which encodes the transcription regulator protein IKAP 48. This position is the last of the intronic nucleotides that establish base‐pairing interactions with the 5′ end of U1 snRNA as part of the initial step in 5′ SS recognition (Fig 1A). Just the lack of this single base pair leads to defects in 5′ SS identification and in exon definition such that the whole exon 20 is skipped, generating an mRNA with a premature stop codon and defective expression of IKAP 49. The critical role of this single base pair became evident in experimental systems where restoring base‐pairing between the mutated 5′ SS and U1 snRNA also restored exon 20 inclusion 50. Remarkably, the extent of the splicing defect is tissue dependent, being very limited in lymphoblasts but extensive in the brain, explaining the severe brain abnormalities and demyelination‐associated symptoms of the disease 51. The basis for the tissue‐specific effect of the mutation remains obscure.

More than 2,500 sequences may function as 5′ SS 52. It is thus not surprising that small sequence variations can lead to the activation of cryptic splice sites, as dramatically illustrated by Hutchinson–Gilford Progeria, a premature aging syndrome where most affected individuals harbor a single C>T silent mutation in exon 11. The mutation activates a cryptic 5′ SS, leading to an mRNA encoding a dominant negative form of lamin A (progerin) that causes nuclear and genomic instability. The balance between the activities of the SR proteins SRSF1 and SRSF6 determines the level of cryptic site activation 53, which can be modulated using antisense oligonucleotides or morpholinos, with therapeutic effects in cell and mouse models of the disease 54, 55. Strikingly, it has been proposed that even the wild‐type sequence can be used as a 5′ SS and that its use increases with age, possibly contributing to physiological aging 54.

Another example of how single nucleotide changes near 5′ SS regions can dramatically affect splicing outcomes and disease is tauopathies associated with mutations in exon 10 of the Microtubule Associated Protein Tau (MAPT) gene. These mutations, found in thirteen families with the autosomal dominant condition frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTPD‐17), alter the ratio between spliced isoforms, promoting exon inclusion and leading to Tau protein aggregation, which has been linked with personality disturbances, dementia, and motor dysfunction 56. The mutations are not located at the splice sites, but rather induce the opening of an RNA stem‐loop that normally partially sequesters the 5′ SS, preventing full inclusion of exon 10 56, 57. This in fact provides one of the best‐documented examples of how secondary structures in the pre‐mRNA can influence splice site recognition.

A now classical example of how sequence variation in exonic sequences can influence exon recognition with profound consequences for human disease is spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). SMA is one of the most frequent genetic diseases, an autosomal recessive neuromuscular disorder characterized by the selective loss of spinal motor neurons, leading to severe skeletal muscle weakness and atrophy. SMA etiology relates to insufficient amount of SMN protein whose function is to chaperone the biogenesis and assembly of snRNPs 12. SMN insufficiency results from loss‐of‐function mutations or deletion of the Survival Motor Neuron 1 gene (SMN1) 58. Despite its high homology to SMN1, the SMN2 gene fails to prevent SMA development due to a synonymous nucleotide difference, C6T, in exon 7, which causes exon 7 skipping and generation of a truncated, unstable, and rapidly degraded version of the SMN protein 59. Understanding the mechanisms behind the differential effects of C vs. T on exon 7 splicing may indeed be instrumental to offer novel therapeutic approaches because the penetrance of the disease is inversely correlated with the levels of exon 7 inclusion in SMN2, which differ in different patient populations 60. Extensive analyses of the mechanistic impact of the C>T transition initially revealed the loss of an ESE recognized by the SR protein SRSF1 as well as the gain of an ESS recognized by hnRNPA1 61, 62. Later work revealed additional contributions of intronic silencers that collectively repress exon 7 63, 64, 65. SMA can be considered as a complex multifactorial pathology as the absence of SMN implies perturbations of the snRNP repertoire with widespread splicing changes 66 and also correlates with splicing alterations of U12 minor spliceosome‐dependent events in mouse and Drosophila SMA models 67, 68, 69. A key and still largely unresolved question is why reduced/unbalanced snRNP production leads to a specific motor neuron defect rather than ubiquitously compromising multiple aspects of RNA processing and gene expression and therefore the function of most cell types.

Trans‐acting factor mutations and alterations: breaking the splicing machinery

Perhaps the first pathology identified with a link to components of the splicing machinery was systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), a condition in which antibodies against nuclear antigens, including almost invariably Sm proteins (present in U1, U2, U4, and U5 snRNP), induce complex acute autoimmune responses 70. Strikingly, mutations in genes encoding protein components of the core splicing machinery and snRNP biogenesis are often associated with distinct pathological conditions and most likely with splicing alterations affecting specific subsets of splicing events 5, 40, opening interesting and challenging questions about the requirement of these factors for pre‐mRNA splicing in general. Answers to these specificity issues may bring key insights into the physiopathology of these diseases and also inform possible therapeutic routes (Figs 3B and 4).

Mutations affecting snRNP biogenesis

As described above, mutation of the SMN1 gene leads to defects in snRNP biogenesis and altered snRNP characteristics in the prevalent motor neuron disease SMA. Interesting possible molecular links involving snRNP function in SMA and other motor/neurodegenerative disorders have emerged. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a common motor/neurodegenerative disease caused by mutations in over 20 genes with different functions 71, including the RNA‐binding proteins FUS and TDP‐43. FUS is an hnRNP‐like protein that interacts with U1 and U2 snRNAs 72, 73, 74. FUS mutant proteins also bind to these snRNAs but are retained in the cytoplasm, causing a reduction in the pool of U1 and U2 snRNPs in the nucleus. Furthermore, FUS interacts with SMN and mutated FUS proteins also appear to alter the cellular localization of SMN, potentially contributing also to disease‐related splicing alterations 75, 76. TDP‐43, another RNA‐binding protein frequently mutated in ALS, interacts with FUS 76 and its dysregulation also affects SMN localization and snRNA abundance 77. Recent results indicate that TDP‐43 represses splicing of cryptic exons and that activation of these exons in TPD‐43‐deficient embryonic stem cells induces cell death 78. However, the multifunctional nature of TDP‐43, FUS, and other related factors makes it difficult to restrict their pathogenic effects to splicing alterations.

TDP‐43 forms insoluble aggregates 79, which is a hallmark of other neurodegenerative diseases as well, such as Alzheimer's disease (AD) or Parkinson's disease. The recent sequencing of the protein content of AD aggregates uncovered the accumulation of several U1 snRNP components 80, and immunohistochemical analyses revealed that U1‐70K and U1A form tangle‐like aggregates in the cytoplasm of AD brain samples, but not in other neurodegenerative diseases. Furthermore, RNA‐Seq analyses revealed global splicing defects, with accumulation of unspliced RNAs, in AD samples 80, suggesting a possible role for RNA processing in the etiology of the disease. Interestingly, silencing of U1‐70K in HEK293 cells led to an increase in amyloid precursor protein (APP), suggesting a possible role for pre‐mRNA splicing in APP metabolism 80. Taken together, these observations imply that alterations in snRNP accumulation and consequently pre‐mRNA splicing can contribute to the etiology of multiple neurodegenerative disorders, perhaps through common mechanisms and targets.

Alterations in U6 snRNA biogenesis have been detected in Clericuzio‐type poikiloderma with neutropenia (PN), a rare autosomal recessive skin disease frequently associated with chronic neutropenia and bone marrow abnormalities potentially leading to myelodysplasia and increased risk of leukemic transformation 81. The disease is associated with mutations in the C16orf57 gene encoding hMpn1/Usb1 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87. This 3′→5′ exoribonuclease is involved in correct processing of U6 snRNA, removing a tail of uridine residues, and generating a characteristic 2′‐3′cyclic phosphate that stabilizes the snRNA 81. Reduced levels of this enzyme in lymphoblasts from PN patients result in higher U6 snRNA degradation. However, no global perturbation of splicing was observed in these cells 81, which is remarkable considering the critical role that U6 snRNA plays in the two catalytic steps of the splicing process. These results suggest that the disease is either associated with specific discrete effects in splicing of certain target RNAs, or that the enzyme plays roles in the metabolism of other RNA classes.

A common concept underlying these examples is that limiting amounts of particular snRNPs exert discrete molecular effects that result in tissue‐specific phenotypic disturbances, suggesting that the levels of snRNPs may be tuned in a cell type‐specific manner for achieving physiological gene regulation.

Mutations in core spliceosomal proteins

Recent whole‐genome and whole‐exome sequencing data of abnormal blood cells from patients with hematopoietic disorders of both lymphoid and myeloid lineages, including myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), revealed recurrent somatic mutations in genes encoding splicing factors. These include proteins involved in 3′ SS recognition, like the two U2AF subunits, SF1/BBP or ZRSR2, and components of U2 snRNP subcomplexes, like SF3A1 and SF3B1 88, 89, 90. Mutations were also found in PRP40, a protein involved in bridging 5′ and 3′ SS‐recognizing complexes, and in SRSF2, a splicing regulator of the SR protein family 89 (see below). The most frequently mutated factor was SF3B1, which plays a key role in splice site recognition. Its interactions with U2AF and the pre‐mRNA contribute to U2 snRNP recruitment, its phosphorylation is coupled with splicing catalysis, and even its association with chromatin influences splicing outcomes 91, 92, 93. SF3B1 mutations have been identified in up to 85% of MDS patients with refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts (RARS), 15% of CLL and 5% of AML and CMML patients. Strikingly, while SF3B1 mutations correlate with favorable prognosis in MDS, they correlate with unfavorable prognosis and resistance to fludarabine in CLL 88, 94, suggesting that the molecular effects of these mutations are strongly influenced by the cellular context. This concept is further highlighted by the recent identification of mutations in another component of the U2 snRNP‐associated SF3B subcomplex (SF3B4) in patients with Nager syndrome, an acrofacial dysostoses characterized by craniofacial and limb malformations 95. Of interest, ultra‐deep sequencing analyses of blood DNA from over 4,000 individuals revealed that expansion of hematopoietic clones harboring mutations in SF3B1 and SRSF2 greatly increases with age, consistent with the higher incidence of MDS in advanced age 96.

The common concept emerging from follow‐up transcriptome studies is that mutations in these core spliceosomal components display specific, rather than global effects on splice site recognition, leading to alterations in the profiles of mRNAs and their isoforms that can explain at least part of the associated phenotypes 97, 98. For example, expression of a mutated U2AF35 protein in transgenic mice led to altered hematopoiesis correlating with splicing alterations in RNA processing and ribosomal genes (possibly triggering a cascade of posttranscriptional changes) and in genes frequently mutated in MDS and AML 98.

Classical views of splicing regulation involve the initial steps of spliceosome assembly as the targets of splicing regulators 22. It would therefore be expected that splicing factors involved in later steps of the process would be more generally required and their mutation more detrimental for intron removal. However, mutations in components of the U4/U6/U5 tri‐snRNP also lead to very specific syndromes or disease conditions. For example, mutations in the EFTUD2 gene, which encodes the U5‐116 kDa component of the U5 snRNP, are responsible for mandibulofacial dysostosis with microcephaly (MFDM), a multiple malformation syndrome 99. Moreover, mutations in PRPF31, PRPF8, PRPF6, PRPF3, PAP‐1, and SNRNP200/BRR2, some of which are involved in the latest spliceosomal rearrangements leading to splicing catalysis, have been causally linked with retinitis pigmentosa (RP), a large group of inherited degenerative disorders of the retina characterized by progressive misfunction of the photoreceptors and the pigment epithelium of the eye 100. Why should mutations in splicing factors key for the catalytic process lead to a tissue‐specific pathology? One possibility is that reduced splicing activity may be more detrimental for rapidly dividing cell types in tissues requiring fast regeneration, like the retina. As a matter of fact, a genome‐wide screen for factors important for correct cell division revealed a substantial enrichment in spliceosomal components 101. Recent reports argue that splicing of genes encoding proteins involved in sister chromatid cohesion and removal of cohesion at the metaphase–anaphase transition, including sororin and APC2, are particularly sensitive to decreased function of splicing factors, including U2AF, components of the SF3A, SF3B, and NTC complex, SNW1, PRPF8, and UBL5, a spliceosome‐associated ubiquitin‐like protein 102, 103, 104, 105. Detailed structure–function studies revealed that positive regulation and negative regulation of the U4/6 unwinding activity of BRR2 by PRPF8 play key roles in proper activation of splicing catalysis 106, 107. Strikingly, the effects of mutants associated with the most severe forms of RP (RP13) can be correlated with this intermittent block of BRR2 activity 108. This may reflect the impact of these mutations in splicing in general, in splicing of specific introns (e.g., sororin, APC2), or lead to differential splice site selection and alternative splicing changes, as observed upon knockdown of tri‐snRNP components including BRR2 and PRPF8 29.

While less abundant and of more restricted effects in RNA metabolism, the minor spliceosome can also be the target of disease‐causing mutations. Thus, mutations in the gene encoding U4atac snRNA are responsible for the microcephalic osteodysplastic primordial dwarfism type 1 (MOPD1, also known as Taybi–Linder syndrome), characterized by neurological and skeletal abnormalities 109, 110, and aberrant splicing of U12‐type introns is also the hallmark of mutations in ZRSR2 found in MDS 111.

Mutations and misregulation of splicing regulators

Considering the strong impact of alternative splicing in cancer 9, it is not surprising that regulatory factors also appear frequently mutated, or their expression changed, in a variety of tumors 8, 112, 113 (Fig 3B). These include SR (e.g., SRSF1, SRSF2, SRSF6) and hnRNP (A1, I, H) as well as other families of regulatory proteins like TIA‐1/TIAR, Sam68, HuR, NOVA, SON, RBM5, and RBM10 40. Some selected examples illustrate this point. SRSF1 is upregulated in multiple tumors, partly by gene amplification, and this is sufficient to transform cells by modulating alternative splicing of tumor suppressor and kinase genes, including S6K1—resulting in cell transformation 114, and Ron—leading to increased cell motility and metastasis 115. Mutations in the SR protein SRSF2 contribute to myelodysplasia by modifying the protein's RNA‐binding specificity, thus differentially regulating the activity of exonic enhancers and causing misregulation of key hemaetopoietic regulators 116, 117, 118. hnRNP I/PTB and hnRNP A1/B2 are upregulated in glioblastomas by Myc oncogene activation and this leads to a switch in pyruvate kinase alternative splicing resulting in efficient energy production in cancer cells by aerobic glycolysis 119. RBM10 is one of the most frequently mutated genes in lung adenocarcinomas 120, and a mutant version of the protein fails to regulate alternative splicing of the Notch pathway regulator NUMB, thus favoring cell proliferation 121. Interestingly, mutations in RBM10 also cause TARP (Talipes equinovarus, Atrial septal defects, Robin sequence, and Persistent left superior vena cava) syndrome, a congenital disorder characterized by palate and jaw abnormalities, clubfoot, and cardiac defects, correlating with dysregulation of multiple alternative splicing events 122. This variety of phenotypes of RBM10 mutations illustrates the multiple—but discrete—functions of splicing regulators during cell differentiation and development.

Mutations in splicing regulators have also been described in several neurodegenerative diseases, such as ALS and frontotemporal lobar degeneration (mutations in TDP‐43 and FUS), autism (mutations in RBFOX1) 40, and Huntington's disease (mutations in SRSF6, see below). Recently, a class of microexons (3–15 nucleotides in length) was discovered that are specifically included in neurons and which are frequently misregulated in patients with autism 123. It will be of particular interest to investigate whether mutations or changes in activity of key regulators, including the SR protein SR100/SRRM4, can explain the disruption in the program of microexon inclusion associated with autistic disorders.

Nucleotide repeat expansions: titrating splicing factors (and more)

The best‐understood disease associated with microsatellite expansions is myotonic dystrophy (DM), where expanded CTG repeats in the 3′ UTR of the DMPK gene and expanded CCTG repeats in intron 1 of the ZNF9 gene act as gain of function mutations responsible for type 1 (DM1) and type 2 DM (DM2), respectively 5, 6, 124, 125. The expanded CUG and CCUG repeats in the pre‐mRNAs of these genes can fold on themselves to form relatively long stretches of double‐stranded RNA, with two distinct molecular consequences impacting on the function of splicing regulators (Fig 3C). On the one hand, the repeats, which accumulate in nuclear foci, are bound by and sequester MBNL1, a regulator of AS important for cell differentiation 126. On the other hand, CUG repeats stabilize CUG‐binding protein 1 (CUG‐BP1) via increased phosphorylation mediated by the activation of PKC 127. The combined effects of decreasing MBNL1 and increasing CUG‐BP1 activity lead to changes in developmentally regulated AS that can explain key features of the disease. For example, delayed muscle relaxation (myotonia) is related to aberrant inclusion of an ORF‐disrupting alternative exon in the muscle‐specific chloride channel CLNC1 128, 129, while insulin resistance is related to an exon‐skipping event in the insulin receptor pre‐mRNA that leads to the production of a less sensitive receptor 130. The multiple effects of changes in the activities of splicing regulatory factors in DM illustrate the combinatorial nature and developmental logic of AS regulation. It also illustrates how, despite these multi‐systemic effects, particular phenotypes can be attributed to specific AS changes, and be reversed by these key targets 131.

DM can serve as a paradigm to understand other disorders caused by repeat expansions (Fig 3C) 5, including some forms of ALS, fragile X‐associated tremor/ataxia, spinocerebellar ataxia, and, possibly, also Huntington's disease (HD). The neurodegenerative HD disorder, characterized by involuntary movements, psychiatric symptoms, and dementia, is caused by CAG repeat expansions in Hungtingtin (Htt) gene exon 1 132. If the number of CAG repeats is higher than 40, symptoms appear, the number of repeats correlating with the severity and the early appearance of the disease. Classically, the pathological effects of the expansion have been attributed to a gain of function due to the increase in polyglutamine peptides, encoded by the CAG repeats, in the Htt protein. This correlates with the accumulation of Htt or of proteolytic degradation products of its glutamine‐rich N‐terminal region, in inclusion bodies. A recent study reported a cryptic polyadenylation site within Htt intron 1, which becomes activated upon CAG expansion 133. This RNA species is actively translated into shorter polypeptides containing polyglutamine tracts, therefore offering an alternative explanation for the generation of presumably toxic N‐terminal peptides. Interestingly, the SR protein SRSF6 seems to bind to the expanded CAG repeats in these transcripts (which harbor consensus sites for this protein) and may promote inhibition of intron 1 splicing 133, facilitating use of the alternative polyadenylation site. One interesting possible mechanism is that SRSF6 prevents the association of U1 snRNP with the intron 1 5′ SS, explaining both splicing inhibition and cryptic polyadenylation site activation, a common additional function of U1 snRNP binding 134. An interesting link has been recently made between HD and tauopathies 135. In this study, an imbalance between Tau isoforms similar to that found in FTDP‐17 (see section 1) was observed in brains of HD patients, along with Tau protein deposits in neuronal nuclei that contribute to the motor phenotype of Htt transgenic mice. Remarkably, SRSF6 is a known regulator of Tau exon 10 splicing 136, and the association of SRSF6 with CAG‐expanded transcripts (which leads to increased phosphorylation of the protein—somewhat similar to the PKC‐mediated phosphorylation of CUG‐BP1 by CUG repeat expansions in DM1) can potentially explain not only the generation of shorter Htt transcripts, but also the alterations in Tau splicing 135. Therefore, changes in activity of SRSF6 induced by expanded CAG repeats may underlie aberrant RNA processing and protein deposits of both Htt and Tau.

Considering therapeutic approaches

Antisense/splice site switching oligonucleotides (ASO/SSO)

ASO/SSO strategies aim to influence the ratio between mRNA isoforms to restore normal splicing or enforce expression of particular variants with potential therapeutic effects 137. They do so by base pairing with splice sites or splicing regulatory sequences preventing their recognition by the splicing machinery or cognate regulatory factors. Remarkable success of these approaches has been achieved in mouse models of SMA, where 2′‐O‐methyl, phosphothioate‐modified oligonucleotides complementary to an ISS recognized by hnRNP A1 promote inclusion of SMN2 exon 7, restoring functional levels of SMN protein in vivo and reverting SMA‐related symptoms 63, 138 (Fig 4). These ASO display surprisingly persistent effects and, strikingly, systemic administration by subcutaneous injection is even more effective than intracerebroventricular administration, arguing that SMN function in peripheral tissues strongly contributes to disease progression 139. Such approaches are currently under clinical trials for the treatment of SMA and Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) 140. The rationale for the treatment of DMD is that the effect of disease‐causing mutations in the dystrophin gene can be overcome by inducing skipping of the exon containing the mutation (or additional exons to preserve the reading frame). Given the length of the gene, with 79 exons, and the repetitive nature of some of its domains, shorter versions of the protein can provide sufficient activity to restore muscle fiber function (Fig 4). Other strategies involve antisense oligonucleotides blocking or degrading the CUG repeat expansions in DM 141, 142. Variants of U7 snRNA (normally involved in histone 3′ end mRNA processing) have been engineered to harbor antisense, exon‐skipping/promoting sequences, with remarkable effects in patient cells and animal models 143, 144. Recent studies have also explored the potential therapeutic effects of U1 snRNP to correct 5′ SS mutations or generally enhance specific exon recognition (ExSpeU1) by targeting intronic sequences downstream of the 5′ SS, triggering 5′ SS activation 145, 146. Combining antisense‐targeting with other sequences or peptides harboring splicing regulatory activity can also expand the range of modulatory functions of these approaches 147, 148. These examples illustrate how understanding molecular mechanisms of splicing regulation can be instrumental in the design of highly specific therapeutic tools.

Trans‐splicing

Trans‐splicing is a natural process involving splice sites in two different pre‐mRNA transcripts and occurs in a variety of organisms, including protozoa, trypanosomes, and nematodes. It has also been observed in Drosophila and mammalian cells, linked to apoptosis, axon guidance, and the maintenance of cell pluripotency 149, 150. Pre‐mRNA trans‐splicing, trans‐splicing ribozymes, and tRNA‐splicing endonucleases have been proposed as RNA repair strategies of potential therapeutic value 151. Spliceosome‐mediated RNA trans‐splicing (SMaRT) approaches have been anticipated for the treatment of several diseases, including cystic fibrosis 152, SMA 153, DMD 154, and RP 155. The general strategy is to introduce a pre‐trans‐splicing molecule (PTM) containing the sequences to be replaced, preceded by a targeting sequence complementary to an intron in the target RNA and containing also a 3′ SS. Splicing between the 5′ SS of the target intron and the 3′ SS of the PTM leads to chimeric transcripts that restore correct mRNA expression. The main hurdle for the therapeutic application of these technologies remains to enhance the limited in vivo efficacy of the trans‐splicing process.

Small splicing‐modifying molecules

Recent findings have raised significant expectations that small molecules targeting the splicing machinery display specific effects on subsets of splice sites and are potentially useful as therapeutic drugs. Such compounds can also shed light on key mechanisms and alterations of RNA processing associated with complex diseases, including cancer. Three families of natural compounds, fermentation products from Pseudomonas and Streptomyces, display anti‐tumoral properties and target the U2 snRNP SF3B complex 113, 156 (Fig 4). While structurally diverse, these molecules harbor a common pharmacophore and have been used as backbones for the synthesis of other active compounds, including spliceostatin A, meayamycins, E7107, and sudemycins 113, 156, 157. How can small molecules targeting core components of the splicing machinery have cytostatic effects on cancer cells without being generally cytotoxic? One intriguing observation is that cancer cells appear to be particularly sensitive to the molecular effects of these compounds 158. For example, potential therapeutic effects of spliceostatin A were found in melanoma cells that acquire vemurafenib resistance through mutations that alter splicing of BRAF, eliminating its RAS‐binding domain 159, suggesting a special sensitivity of cancer‐associated splicing events. Another explanation is that, at concentrations in which splicing inhibitory drugs exert cytostatic, but not general cytotoxic effects, they do not globally inhibit splicing but rather display selective effects on AS, particularly in genes relevant for cell cycle progression and apoptosis 158, 160. These specific effects may be reminiscent of the effects of SF3B1 mutations frequently found in a variety of tumors, discussed above, suggesting that specific splice site recognition can be tuned either by mutations in, or by small molecules binding to, the SF3B complex. The molecular basis for this specificity remains to be understood, but the drugs appear to interfere, in a sequence context‐dependent manner, with steps leading to the progression and proofreading of spliceosome assembly 160, 161, 162.

Two recent studies demonstrated the potential of high‐throughput drug screens to identify molecules that modulate particular splicing events, specifically to promote SMN2 exon 7 inclusion as possible therapy for SMA 163, 164. Using relatively simple splicing‐based fluorescent reporters, structurally different compounds were identified that promote SMN2 exon 7 inclusion, functional SMN protein expression as well as motor function and survival in mouse models of the disease. Although further transcriptome and mechanistic studies will be required, the effects were remarkably selective and at least one of the compounds appeared to specifically stabilize base pairing between U1 snRNA and particular sequence features of the SMN2 exon 7/intron junction. In this regard, it is interesting that a number of compounds, including kinetin 165, cardiac glycosides 166, and RECTAS 167, have been shown to facilitate recognition of the 5′ SS of the IKBKAP gene mutated in FD, perhaps by stabilizing particular sets of base‐pairing interactions, as proposed for SMN2. Another interesting therapeutic lead would be the use of compounds able to modulate particular secondary pre‐mRNA structures, as shown for MAPT exon 10 168.

It seems likely that a detailed understanding of the mechanisms of splice site recognition and spliceosome assembly, including structural determination of complexes bound to specific substrates in the absence and in the presence of small molecule modulators, will open an almost unexplored territory to regulate gene expression and potentially correct disease‐causing splicing defects.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Sidebar A: In need of answers.

How do mutations that affect core components of the splicing machinery, assumed to be generally necessary for intron removal, lead to cell‐ or tissue‐type‐specific phenotypes, for example, in motoneurons (SMA) or in retinal cells (retinitis pigmentosa)?

A related question is, how do small molecules targeting core splicing components display selective, potentially therapeutic effects (e.g., antiproliferative effects on cancer cells) without generally compromising the splicing process?

Does the complexity of the spliceosome (with its dynamic compositional and conformational changes) offer a rich targetable space for small molecule‐based therapies?

Can further chemical modifications and delivery methods generalize the use of antisense oligonucleotide‐based approaches as splicing modulation tools for biomedical research and gene‐specific therapies?

Can the effects of multifunctional RNA‐binding proteins (e.g., TDP‐43, FUS), often involved in the coupling between gene regulation steps, be dissected to identify key target genes and processes with therapeutic potential?

Will a detailed picture of cell type‐specific splicing regulatory networks (including mutual influences between RNA‐binding proteins) provide a better understanding of disease etiology and the rational design of therapeutic approaches?

Acknowledgements

We apologize to many colleagues whose work could not be directly referenced because of space constraints. We thank members of our laboratory for comments on the manuscript. Work in JV laboratory is supported by Fundación Botín, Banco de Santander through its Santander Universities Global Division, Consolider RNAREG, Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad, and AGAUR. GD is supported by the Marie Sklodowska Curie Fellowship Program.

EMBO Reports (2015) 16: 1640–1655

See the Glossary for abbreviations used in this article.

References

- 1. Moore MJ, Proudfoot NJ (2009) Pre‐mRNA processing reaches back to transcription and ahead to translation. Cell 136: 688–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pan Q, Shai O, Lee LJ, Frey BJ, Blencowe BJ (2008) Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high‐throughput sequencing. Nat Genet 40: 1413–1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barbosa‐Morais NL, Irimia M, Pan Q, Xiong HY, Gueroussov S, Lee LJ, Slobodeniuc V, Kutter C, Watt S, Colak R et al (2012) The evolutionary landscape of alternative splicing in vertebrate species. Science 338: 1587–1593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Merkin J, Russell C, Chen P, Burge CB (2012) Evolutionary dynamics of gene and isoform regulation in Mammalian tissues. Science 338: 1593–1599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cooper TA, Wan L, Dreyfuss G (2009) RNA and disease. Cell 136: 777–793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ward AJ, Cooper TA (2010) The pathobiology of splicing. J Pathol 220: 152–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li DK, Tisdale S, Lotti F, Pellizzoni L (2014) SMN control of RNP assembly: from post‐transcriptional gene regulation to motor neuron disease. Semin Cell Dev Biol 32: 22–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Biamonti G, Catillo M, Pignataro D, Montecucco A, Ghigna C (2014) The alternative splicing side of cancer. Semin Cell Dev Biol 32: 30–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Oltean S, Bates DO (2014) Hallmarks of alternative splicing in cancer. Oncogene 33: 5311–5318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Linder B, Fischer U, Gehring NH (2015) mRNA metabolism and neuronal disease. FEBS Lett 589: 1598–1606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fredericks AM, Cygan KJ, Brown BA, Fairbrother WG (2015) RNA‐binding proteins: splicing factors and disease. Biomolecules 5: 893–909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Matera AG, Wang Z (2014) A day in the life of the spliceosome. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 15: 108–121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kornblihtt AR, Schor IE, Allo M, Dujardin G, Petrillo E, Munoz MJ (2013) Alternative splicing: a pivotal step between eukaryotic transcription and translation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 14: 153–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wahl MC, Will CL, Luhrmann R (2009) The spliceosome: design principles of a dynamic RNP machine. Cell 136: 701–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wahl MC, Luhrmann R (2015) SnapShot: spliceosome dynamics I. Cell 161: 1474–e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wahl MC, Luhrmann R (2015) SnapShot: spliceosome dynamics II. Cell 162: 456–e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Berget SM (1995) Exon recognition in vertebrate splicing. J Biol Chem 270: 2411–2414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. House AE, Lynch KW (2006) An exonic splicing silencer represses spliceosome assembly after ATP‐dependent exon recognition. Nat Struct Mol Biol 13: 937–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bonnal S, Martinez C, Forch P, Bachi A, Wilm M, Valcarcel J (2008) RBM5/Luca‐15/H37 regulates Fas alternative splice site pairing after exon definition. Mol Cell 32: 81–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sharma S, Maris C, Allain FH, Black DL (2011) U1 snRNA directly interacts with polypyrimidine tract‐binding protein during splicing repression. Mol Cell 41: 579–588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Will CL, Luhrmann R (2011) Spliceosome structure and function. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3: a003707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen M, Manley JL (2009) Mechanisms of alternative splicing regulation: insights from molecular and genomics approaches. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10: 741–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fu XD, Ares M Jr (2014) Context‐dependent control of alternative splicing by RNA‐binding proteins. Nat Rev Genet 15: 689–701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Barash Y, Calarco JA, Gao W, Pan Q, Wang X, Shai O, Blencowe BJ, Frey BJ (2010) Deciphering the splicing code. Nature 465: 53–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Braunschweig U, Gueroussov S, Plocik AM, Graveley BR, Blencowe BJ (2013) Dynamic integration of splicing within gene regulatory pathways. Cell 152: 1252–1269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Collins CA, Guthrie C (1999) Allele‐specific genetic interactions between Prp8 and RNA active site residues suggest a function for Prp8 at the catalytic core of the spliceosome. Genes Dev 13: 1970–1982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nilsen TW, Graveley BR (2010) Expansion of the eukaryotic proteome by alternative splicing. Nature 463: 457–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Clark TA, Sugnet CW, Ares M Jr (2002) Genomewide analysis of mRNA processing in yeast using splicing‐specific microarrays. Science 296: 907–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Papasaikas P, Tejedor JR, Vigevani L, Valcarcel J (2015) Functional splicing network reveals extensive regulatory potential of the core spliceosomal machinery. Mol Cell 57: 7–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tejedor JR, Papasaikas P, Valcarcel J (2015) Genome‐wide identification of Fas/CD95 alternative splicing regulators reveals links with iron homeostasis. Mol Cell 57: 23–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dujardin G, Lafaille C, Petrillo E, Buggiano V, Gomez Acuna LI, Fiszbein A, Godoy Herz MA, Nieto Moreno N, Munoz MJ, Allo M et al (2013) Transcriptional elongation and alternative splicing. Biochim Biophys Acta 1829: 134–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dujardin G, Lafaille C, de la Mata M, Marasco LE, Munoz MJ, Le Jossic‐Corcos C, Corcos L, Kornblihtt AR (2014) How slow RNA polymerase II elongation favors alternative exon skipping. Mol Cell 54: 683–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Iannone C, Valcarcel J (2013) Chromatin's thread to alternative splicing regulation. Chromosoma 122: 465–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Luco RF, Allo M, Schor IE, Kornblihtt AR, Misteli T (2011) Epigenetics in alternative pre‐mRNA splicing. Cell 144: 16–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Heyd F, Lynch KW (2011) Degrade, move, regroup: signaling control of splicing proteins. Trends Biochem Sci 36: 397–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pagani F, Raponi M, Baralle FE (2005) Synonymous mutations in CFTR exon 12 affect splicing and are not neutral in evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 6368–6372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Serra E, Ars E, Ravella A, Sanchez A, Puig S, Rosenbaum T, Estivill X, Lazaro C (2001) Somatic NF1 mutational spectrum in benign neurofibromas: mRNA splice defects are common among point mutations. Hum Genet 108: 416–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lim KH, Ferraris L, Filloux ME, Raphael BJ, Fairbrother WG (2011) Using positional distribution to identify splicing elements and predict pre‐mRNA processing defects in human genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 11093–11098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Padgett RA (2012) New connections between splicing and human disease. Trends Genet 28: 147–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Singh RK, Cooper TA (2012) Pre‐mRNA splicing in disease and therapeutics. Trends Mol Med 18: 472–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sterne‐Weiler T, Howard J, Mort M, Cooper DN, Sanford JR (2011) Loss of exon identity is a common mechanism of human inherited disease. Genome Res 21: 1563–1571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gnad F, Baucom A, Mukhyala K, Manning G, Zhang Z (2013) Assessment of computational methods for predicting the effects of missense mutations in human cancers. BMC Genom 14(Suppl 3): S7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sauna ZE, Kimchi‐Sarfaty C (2011) Understanding the contribution of synonymous mutations to human disease. Nat Rev Genet 12: 683–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Supek F, Minana B, Valcarcel J, Gabaldon T, Lehner B (2014) Synonymous mutations frequently act as driver mutations in human cancers. Cell 156: 1324–1335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Xiong HY, Alipanahi B, Lee LJ, Bretschneider H, Merico D, Yuen RK, Hua Y, Gueroussov S, Najafabadi HS, Hughes TR et al (2015) RNA splicing. The human splicing code reveals new insights into the genetic determinants of disease. Science 347: 1254806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sterne‐Weiler T, Sanford JR (2014) Exon identity crisis: disease‐causing mutations that disrupt the splicing code. Genome Biol 15: 201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mort M, Sterne‐Weiler T, Li B, Ball EV, Cooper DN, Radivojac P, Sanford JR, Mooney SD (2014) MutPred splice: machine learning‐based prediction of exonic variants that disrupt splicing. Genome Biol 15: R19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Anderson SL, Coli R, Daly IW, Kichula EA, Rork MJ, Volpi SA, Ekstein J, Rubin BY (2001) Familial dysautonomia is caused by mutations of the IKAP gene. Am J Hum Genet 68: 753–758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ibrahim EC, Hims MM, Shomron N, Burge CB, Slaugenhaupt SA, Reed R (2007) Weak definition of IKBKAP exon 20 leads to aberrant splicing in familial dysautonomia. Hum Mutat 28: 41–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Carmel I, Tal S, Vig I, Ast G (2004) Comparative analysis detects dependencies among the 5′ splice‐site positions. RNA 10: 828–840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cuajungco MP, Leyne M, Mull J, Gill SP, Lu W, Zagzag D, Axelrod FB, Maayan C, Gusella JF, Slaugenhaupt SA (2003) Tissue‐specific reduction in splicing efficiency of IKBKAP due to the major mutation associated with familial dysautonomia. Am J Hum Genet 72: 749–758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Roca X, Krainer AR (2009) Recognition of atypical 5′ splice sites by shifted base‐pairing to U1 snRNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol 16: 176–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lopez‐Mejia IC, Vautrot V, De Toledo M, Behm‐Ansmant I, Bourgeois CF, Navarro CL, Osorio FG, Freije JM, Stevenin J, De Sandre‐Giovannoli A et al (2011) A conserved splicing mechanism of the LMNA gene controls premature aging. Hum Mol Genet 20: 4540–4555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Scaffidi P, Misteli T (2005) Reversal of the cellular phenotype in the premature aging disease Hutchinson‐Gilford progeria syndrome. Nat Med 11: 440–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Osorio FG, Navarro CL, Cadinanos J, Lopez‐Mejia IC, Quiros PM, Bartoli C, Rivera J, Tazi J, Guzman G, Varela I et al (2011) Splicing‐directed therapy in a new mouse model of human accelerated aging. Sci Transl Med 3: 106ra107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hutton M, Lendon CL, Rizzu P, Baker M, Froelich S, Houlden H, Pickering‐Brown S, Chakraverty S, Isaacs A, Grover A et al (1998) Association of missense and 5′‐splice‐site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP‐17. Nature 393: 702–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Grover A, Houlden H, Baker M, Adamson J, Lewis J, Prihar G, Pickering‐Brown S, Duff K, Hutton M (1999) 5′ splice site mutations in tau associated with the inherited dementia FTDP‐17 affect a stem‐loop structure that regulates alternative splicing of exon 10. J Biol Chem 274: 15134–15143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lefebvre S, Burglen L, Reboullet S, Clermont O, Burlet P, Viollet L, Benichou B, Cruaud C, Millasseau P, Zeviani M et al (1995) Identification and characterization of a spinal muscular atrophy‐determining gene. Cell 80: 155–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lorson CL, Hahnen E, Androphy EJ, Wirth B (1999) A single nucleotide in the SMN gene regulates splicing and is responsible for spinal muscular atrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 6307–6311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Monani UR, De Vivo DC (2014) Neurodegeneration in spinal muscular atrophy: from disease phenotype and animal models to therapeutic strategies and beyond. Future Neurol 9: 49–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Cartegni L, Krainer AR (2002) Disruption of an SF2/ASF‐dependent exonic splicing enhancer in SMN2 causes spinal muscular atrophy in the absence of SMN1. Nat Genet 30: 377–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kashima T, Manley JL (2003) A negative element in SMN2 exon 7 inhibits splicing in spinal muscular atrophy. Nat Genet 34: 460–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hua Y, Vickers TA, Okunola HL, Bennett CF, Krainer AR (2008) Antisense masking of an hnRNP A1/A2 intronic splicing silencer corrects SMN2 splicing in transgenic mice. Am J Hum Genet 82: 834–848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Singh NK, Singh NN, Androphy EJ, Singh RN (2006) Splicing of a critical exon of human Survival Motor Neuron is regulated by a unique silencer element located in the last intron. Mol Cell Biol 26: 1333–1346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Singh NN, Singh RN (2011) Alternative splicing in spinal muscular atrophy underscores the role of an intron definition model. RNA Biol 8: 600–606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Zhang Z, Lotti F, Dittmar K, Younis I, Wan L, Kasim M, Dreyfuss G (2008) SMN deficiency causes tissue‐specific perturbations in the repertoire of snRNAs and widespread defects in splicing. Cell 133: 585–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lotti F, Imlach WL, Saieva L, Beck ES, Hao le T, Li DK, Jiao W, Mentis GZ, Beattie CE, McCabe BD et al (2012) An SMN‐dependent U12 splicing event essential for motor circuit function. Cell 151: 440–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Imlach WL, Beck ES, Choi BJ, Lotti F, Pellizzoni L, McCabe BD (2012) SMN is required for sensory‐motor circuit function in Drosophila . Cell 151: 427–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kariya S, Obis T, Garone C, Akay T, Sera F, Iwata S, Homma S, Monani UR (2014) Requirement of enhanced Survival Motoneuron protein imposed during neuromuscular junction maturation. J Clin Invest 124: 785–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Mahler M (2011) Sm peptides in differentiation of autoimmune diseases. Adv Clin Chem 54: 109–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Renton AE, Chio A, Traynor BJ (2014) State of play in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis genetics. Nat Neurosci 17: 17–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Gerbino V, Carri MT, Cozzolino M, Achsel T (2013) Mislocalised FUS mutants stall spliceosomal snRNPs in the cytoplasm. Neurobiol Dis 55: 120–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Vance C, Rogelj B, Hortobagyi T, De Vos KJ, Nishimura AL, Sreedharan J, Hu X, Smith B, Ruddy D, Wright P et al (2009) Mutations in FUS, an RNA processing protein, cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis type 6. Science 323: 1208–1211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kwiatkowski TJ Jr, Bosco DA, Leclerc AL, Tamrazian E, Vanderburg CR, Russ C, Davis A, Gilchrist J, Kasarskis EJ, Munsat T et al (2009) Mutations in the FUS/TLS gene on chromosome 16 cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science 323: 1205–1208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Yamazaki T, Chen S, Yu Y, Yan B, Haertlein TC, Carrasco MA, Tapia JC, Zhai B, Das R, Lalancette‐Hebert M et al (2012) FUS‐SMN protein interactions link the motor neuron diseases ALS and SMA. Cell Rep 2: 799–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Groen EJ, Fumoto K, Blokhuis AM, Engelen‐Lee J, Zhou Y, van den Heuvel DM, Koppers M, van Diggelen F, van Heest J, Demmers JA et al (2013) ALS‐associated mutations in FUS disrupt the axonal distribution and function of SMN. Hum Mol Genet 22: 3690–3704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Ishihara T, Ariizumi Y, Shiga A, Kato T, Tan CF, Sato T, Miki Y, Yokoo M, Fujino T, Koyama A et al (2013) Decreased number of Gemini of coiled bodies and U12 snRNA level in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet 22: 4136–4147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Ling JP, Pletnikova O, Troncoso JC, Wong PC (2015) NEURODEGENERATION. TDP‐43 repression of nonconserved cryptic exons is compromised in ALS‐FTD. Science 349: 650–655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, Truax AC, Micsenyi MC, Chou TT, Bruce J, Schuck T, Grossman M, Clark CM et al (2006) Ubiquitinated TDP‐43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science 314: 130–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Bai B, Hales CM, Chen PC, Gozal Y, Dammer EB, Fritz JJ, Wang X, Xia Q, Duong DM, Street C et al (2013) U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein complex and RNA splicing alterations in Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 16562–16567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Shchepachev V, Wischnewski H, Missiaglia E, Soneson C, Azzalin CM (2012) Mpn1, mutated in poikiloderma with neutropenia protein 1, is a conserved 3′‐to‐5′ RNA exonuclease processing U6 small nuclear RNA. Cell Rep 2: 855–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Arnold AW, Itin PH, Pigors M, Kohlhase J, Bruckner‐Tuderman L, Has C (2010) Poikiloderma with neutropenia: a novel C16orf57 mutation and clinical diagnostic criteria. Br J Dermatol 163: 866–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Chantorn R, Shwayder T (2012) Poikiloderma with neutropenia: report of three cases including one with calcinosis cutis. Pediatr Dermatol 29: 463–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Clericuzio C, Harutyunyan K, Jin W, Erickson RP, Irvine AD, McLean WH, Wen Y, Bagatell R, Griffin TA, Shwayder TA et al (2011) Identification of a novel C16orf57 mutation in Athabaskan patients with Poikiloderma with Neutropenia. Am J Med Genet A 155A: 337–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Colombo EA, Bazan JF, Negri G, Gervasini C, Elcioglu NH, Yucelten D, Altunay I, Cetincelik U, Teti A, Del Fattore A et al (2012) Novel C16orf57 mutations in patients with Poikiloderma with Neutropenia: bioinformatic analysis of the protein and predicted effects of all reported mutations. Orphanet J Rare Dis 7: 7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Concolino D, Roversi G, Muzzi GL, Sestito S, Colombo EA, Volpi L, Larizza L, Strisciuglio P (2010) Clericuzio‐type poikiloderma with neutropenia syndrome in three sibs with mutations in the C16orf57 gene: delineation of the phenotype. Am J Med Genet A 152A: 2588–2594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Volpi L, Roversi G, Colombo EA, Leijsten N, Concolino D, Calabria A, Mencarelli MA, Fimiani M, Macciardi F, Pfundt R et al (2010) Targeted next‐generation sequencing appoints c16orf57 as clericuzio‐type poikiloderma with neutropenia gene. Am J Hum Genet 86: 72–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Papaemmanuil E, Cazzola M, Boultwood J, Malcovati L, Vyas P, Bowen D, Pellagatti A, Wainscoat JS, Hellstrom‐Lindberg E, Gambacorti‐Passerini C et al (2011) Somatic SF3B1 mutation in myelodysplasia with ring sideroblasts. N Engl J Med 365: 1384–1395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Yoshida K, Sanada M, Shiraishi Y, Nowak D, Nagata Y, Yamamoto R, Sato Y, Sato‐Otsubo A, Kon A, Nagasaki M et al (2011) Frequent pathway mutations of splicing machinery in myelodysplasia. Nature 478: 64–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Quesada V, Conde L, Villamor N, Ordonez GR, Jares P, Bassaganyas L, Ramsay AJ, Bea S, Pinyol M, Martinez‐Trillos A et al (2012) Exome sequencing identifies recurrent mutations of the splicing factor SF3B1 gene in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat Genet 44: 47–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Gozani O, Potashkin J, Reed R (1998) A potential role for U2AF‐SAP 155 interactions in recruiting U2 snRNP to the branch site. Mol Cell Biol 18: 4752–4760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Wang C, Chua K, Seghezzi W, Lees E, Gozani O, Reed R (1998) Phosphorylation of spliceosomal protein SAP 155 coupled with splicing catalysis. Genes Dev 12: 1409–1414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Kfir N, Lev‐Maor G, Glaich O, Alajem A, Datta A, Sze SK, Meshorer E, Ast G (2015) SF3B1 association with chromatin determines splicing outcomes. Cell Rep 11: 618–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Rossi D, Bruscaggin A, Spina V, Rasi S, Khiabanian H, Messina M, Fangazio M, Vaisitti T, Monti S, Chiaretti S et al (2011) Mutations of the SF3B1 splicing factor in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: association with progression and fludarabine‐refractoriness. Blood 118: 6904–6908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Bernier FP, Caluseriu O, Ng S, Schwartzentruber J, Buckingham KJ, Innes AM, Jabs EW, Innis JW, Schuette JL, Gorski JL et al (2012) Haploinsufficiency of SF3B4, a component of the pre‐mRNA spliceosomal complex, causes Nager syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 90: 925–933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. McKerrell T, Park N, Moreno T, Grove CS, Ponstingl H, Stephens J, Understanding Society Scientific Group , Crawley C, Craig J, Scott MA et al (2015) Leukemia‐associated somatic mutations drive distinct patterns of age‐related clonal hemopoiesis. Cell Rep 10: 1239–1245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Ferreira PG, Jares P, Rico D, Gomez‐Lopez G, Martinez‐Trillos A, Villamor N, Ecker S, Gonzalez‐Perez A, Knowles DG, Monlong J et al (2014) Transcriptome characterization by RNA sequencing identifies a major molecular and clinical subdivision in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Genome Res 24: 212–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Shirai CL, Ley JN, White BS, Kim S, Tibbitts J, Shao J, Ndonwi M, Wadugu B, Duncavage EJ, Okeyo‐Owuor T et al (2015) Mutant U2AF1 expression alters hematopoiesis and Pre‐mRNA splicing in vivo. Cancer Cell 27: 631–643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Lines MA, Huang L, Schwartzentruber J, Douglas SL, Lynch DC, Beaulieu C, Guion‐Almeida ML, Zechi‐Ceide RM, Gener B, Gillessen‐Kaesbach G et al (2012) Haploinsufficiency of a spliceosomal GTPase encoded by EFTUD2 causes mandibulofacial dysostosis with microcephaly. Am J Hum Genet 90: 369–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Mordes D, Luo X, Kar A, Kuo D, Xu L, Fushimi K, Yu G, Sternberg P Jr, Wu JY (2006) Pre‐mRNA splicing and retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Vis 12: 1259–1271 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Neumann B, Walter T, Heriche JK, Bulkescher J, Erfle H, Conrad C, Rogers P, Poser I, Held M, Liebel U et al (2010) Phenotypic profiling of the human genome by time‐lapse microscopy reveals cell division genes. Nature 464: 721–727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]