Abstract

Purpose

Evaluation of the dose distribution for lung cancer patients using a patient set-up procedure based on the bony anatomy or the primary tumor.

Methods and materials

For 39 (non-)small cell lung cancer patients the planning FDG-PET/CT scan was registered to a repeated FDG-PET/CT scan made in the second week of treatment. Two patient set-up methods were analyzed: bony anatomy or primary tumor set-up. The original treatment plan was copied to the repeated scan, and target and normal tissue structures were delineated. Dose distributions were analyzed using dose-volume histograms for the primary tumor, lymph nodes, lungs and spinal cord.

Results

One patient showed decreased dose coverage of the primary tumor due to progressive disease and required re-planning to achieve adequate coverage. For the other patients, the minimum dose to the primary tumor did not significantly deviate from the planned dose: −0.2±1.7% (p=0.71) and −0.1±1.7% (p=0.85) for the bony anatomy and primary tumor set-up, respectively. For patients (N=31) with nodal involvement, 10% showed a decrease in minimum dose larger than 5% for the bony-anatomy set-up and 13% for the primary tumor based set-up. Mean lung dose exceeded the maximum allowed 20 Gy in 21% of the patients for the bony-anatomy and in 13% for the primary tumor set-up, whereas for the spinal cord this occurred in 10% and 13% of the patients, respectively.

Conclusions

In 10% and 13% of patients with nodal involvement, set-up based on bony anatomy or primary tumor, respectively, lead to important dose deviations in nodal target volumes. Overdosage of critical structures occurred in 10-20% of the patients. In case of progressive disease, repeated imaging revealed underdosage of the primary tumor. Development of practical ways for set-up procedures based on repeated high-quality imaging of all tumor sites during radiotherapy should therefore be an important research focus.

Keywords: patient set-up, lung cancer, mediastinal lymph nodes, adaptive radiotherapy, dose distribution, repeated imaging

Introduction

In lung cancer treatment, radiotherapy dose has been increased in many dose-escalation studies and has shown to improve both local control and overall survival at reasonable normal tissue toxicity levels (1, 2). Both the primary tumor and the involved mediastinal lymph nodes are treated in the same treatment plan (3). Changes in volume of the primary tumor during treatment as well as baseline shifts have been described in many studies (4-10). A complicating factor for accurate irradiation is that changes in lymph node position and their volume are not related to corresponding changes in the primary tumor, which hampers the use of the primary tumor as a surrogate for the lymph nodes (11-13).

FDG-PET/CT imaging combined with an intra-venous (i.v.) contrast-enhanced CT scan has become the standard imaging technique in locally advanced lung cancer (14, 15).

In the past, volumetric imaging was restricted to a 3D planning (PET-)CT scan made during the treatment planning procedure, but the recent advances in in-room imaging of predominantly kilovolt (kV) and megavolt (MV) cone-beam CT increased the use of patient alignment based on 3D image information (16). These new techniques give quantitative information on the volume and position of the primary tumor during treatment, but for imaging of the mediastinal lymph nodes they remain suboptimal. Hence, localization and quantification of the mediastinal lymph nodes is difficult in such cone-beam CT images.

These multiple target volumes (primary tumor and lymph nodes) thus result in many regions of interest that can be registered for deriving the actual patient set-up. Patient set-up by registering the bony anatomy is the current state of practice, but also registration of the primary tumor might yield better primary tumor coverage and reduced margins. However, if an integrated elective or involved mediastinal lymph node irradiation in a single treatment plan is used, a match based on the location of the primary tumor might detriment the dose coverage of these nodes. On the other hand, a match of the bony anatomy might cause underdosage of the primary tumor if a baseline shift of the primary tumor occurs during treatment.

PET/CT imaging with i.v. contrast as the most optimal image modality to detect nodal involvement was selected prior to and during treatment. The dose is recalculated inside the repeated CT imaging data set that has all target and normal structures delineated and an analysis is performed in terms of dose parameters and dose coverage of the primary tumor, involved mediastinal lymph nodes and normal tissue. Such an analysis combines the dose distribution based on different patient set-up strategies with possible changes in patient anatomy and tumor volume. The aim of this study was to investigate the accuracy of the treatment plan for set-up procedure based on the bony anatomy or the primary tumor for a large group of unselected patients.

Methods and materials

Patient characteristics, image acquisition and treatment

In the period between June 2008 and December 2008, we prospectively imaged 39 lung cancer patients who received a radical treatment in the second week during treatment. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board and all patients gave informed consent. Both small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients were included. Patients scheduled for stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) were excluded.

Four-dimensional (4D) respiration-correlated (RC) CT imaging was performed for all patients using our standard 4D RC CT imaging protocol together with a 3D FDG-PET image and a 3D CT scan using an intravenous iodine-based contrast medium (XENETIX 300, Guerbet, Aulnay-sous-Bois, France) (4). Imaging was performed on a dedicated PET/CT scanner (Siemens TruePoint Biograph 40, Siemens Molecular Imaging, Knoxville, TN). Patients were positioned in the radiotherapy position using a dedicated arm support. The patient’s breathing was monitored using a pressure sensor in a belt strapped around the patient’s chest (AZ-733 V, Anzai Medical Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The following 4DCT scan parameters were used;120 kV tube voltage, 800 mAs and 3 mm reconstructed slice thickness. The 4D CT was reconstructed in 8 CT phases using an amplitude based binning method. Injected activity (MBq) of FDG depended on the weight (kg) of the patient and was equal to 4 times the body weight plus 20 MBq.

The gross tumor volume of the primary tumor (GTVprim) and involved mediastinal lymph nodes (GTVlymph) were delineated by the radiation oncologist. Expanding the GTVs with a margin of 5 mm resulted in the clinical target volumes (CTVprim and CTVlymph, respectively), the radiation oncologist was allowed to edit the CTV to exclude possible invasion into bony anatomy or blood vessels. The planning target volume of the primary tumor (PTVprim) was defined as the CTVprim with an additional margin of 10 mm. For the PTV of the lymph nodes (PTVlymph) a CTV to PTV margin of 5 mm was used.

The patients were treated according to our clinical protocol. On the 50% exhale phase of the 4D CT scan the target volumes and normal tissues were delineated and used for 3D conformal treatment planning using homogeneity constraints around the target volume of 90% to 115% of the prescribed dose.

For the SCLC patients a dose of 45 Gy is delivered in 30 fractions (17). For the NSCLC patients, a dose-escalation protocol based on normal tissue constraints was used. Patients received no chemotherapy, induction or concurrent chemotherapy with radiotherapy. For the NSCLC patients without chemotherapy or receiving sequential chemo-radiotherapy, a maximum escalated dose up to 79.2 Gy in bi-daily fractions of 1.8 Gy was used, depending on normal tissue constraints. (2, 18, 19). The patients receiving concurrent chemo-radiotherapy a dose-escalation based on normal tissue toxicity up to 69 Gy was performed with first a fractionation scheme of 30 fractions of 1.5 Gy bi-daily and afterwards a dose-escalation with fraction sizes of 2.0 Gy once daily was used.

Repeated imaging during treatment and delineation

Repeated imaging was performed in the second week of radiotherapy treatment. For this imaging session, the FDG-PET/CT scan was acquired using the same protocol as the planning CT scan, including the contrast-enhanced CT scan, with the patient positioned in radiotherapy position. On this repeated scan, the GTVs and CTVs were copied from the planning CT scan and afterwards manually adjusted by a radiation oncologist using the same target volume definitions guidelines as used for the planning scan. The lungs and spinal cord were also delineated on these scans.

Image registration procedure

The CT scans of both time points were manually registered. This rigid registration allowed only translations to mimic the current widely used patient set-up procedure during external beam radiotherapy treatment. Two independent persons performed these registrations based on either the bony anatomy or the primary tumor. For the bony anatomy registration, all the visible bony anatomy in the axial slices surrounding the primary tumor and involved mediastinal lymph nodes were used for the registration. For the tumor match, the GTV of the primary tumor was registered between the planning and the repeated CT scan. The average of the values for the translation vectors in the three orthogonal directions of the two observers were used to calculate the applied set-up vector.

Dose recalculation

The dose distribution was recalculated using the CT scan of the repeated imaging session and applying the original treatment plan including all monitor unit settings and beam parameters but with the isocenter derived from the patient set-up procedure. The two dose distributions were calculated with the isocenter derived from the bony anatomy or the primary tumor registration. Dose distributions were recalculated using the same advanced superposition algorithm implemented in the treatment planning system (XiO 4.5.0, CMS, St. Louis, MO) as used for the treatment planning.

Dose distribution analysis

The dose distribution calculated on the repeated CT scan was compared to the planning CT scan by using dose-volume histogram parameters. For the target volumes, the clinical target volumes (CTV) were taken as the structure of interest because the planning target volume concept is only valid during treatment planning to achieve adequate coverage of the CTV during treatment (20, 21). For both the CTVprim and the CTVlymph, the minimum dose to 99% of the volume of interest (D99%), the mean dose and the volume receiving 90% of the prescribed dose (V90%) were calculated. For the normal tissues, the mean lung dose (MLD) was calculated based on the union of both lungs but with the GTVs excluded from the volume. The maximum dose to 0.1% of the spinal cord (D0.1%) was also calculated.

Statistical evaluation

A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for testing of significance of paired results. Analyses were performed in SPSS (version 17.0, Chicago, IL, USA). Results are presented as mean values ± 1 standard deviation (SD) with the range also indicated and p-values smaller than 0.05 were assumed to be statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

The patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. In total 39 patients were successfully imaged prior to radiotherapy and in the second week of radiotherapy, 4 with SCLC and 35 with NSCLC. For 9 patients, the repeated scan was not available, either due to technical or logistical issues. The average dose received up to the repeated PET/CT imaging was 20.5 ± 4.5 Gy (range 12 to 34.2) delivered in 13.0 ± 2.6 fractions (range 8 to 19). On average there were 16.8 ± 3.0 days (range 11 to 24) between the two imaging sessions and the repeated scan was performed 8.5 ± 1.8 days (range 6 to 13) after the start of radiotherapy. Eighteen patients were treated with concurrent chemo-radiotherapy, nineteen patients with sequential chemotherapy and radiotherapy, and two patients only got radiation treatment. One patient was treated for two primary tumors inside the lung, these primary tumors were analyzed separately for the bony anatomy and primary tumor registration. Thirty-one patients had nodal involvement whereas eight patients were treated only on the primary tumor for they did not have nodal involvement. One patient was excluded because of a complete remission on the repeated scan.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

| Patient Nr |

Age [years] |

Gender | Type | TNM | Localization | Chemotherapy | Time between scans [Days] |

Dose at repeated scan [Gy] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 59 | F | NSCLC | T2N2M0 | LUL | Induction | 16 | 23.4 |

| 2 | 62 | M | NSCLC | T3N3M0 | RML | Induction | 14 | 23.4 |

| 3 | 75 | M | NSCLC | T2N2M0 | RUL | Concurrent | 17 | 19.5 |

| 4 | 51 | M | NSCLC | T2N2M0 | RUL | Concurrent | 13 | 12.0 |

| 5 | 72 | M | NSCLC | T3N2M0 | RUL | Induction | 15 | 19.5 |

| 6 | 72 | M | NSCLC | T1N1M1 | RUL | No chemo | 12 | 16.2 |

| 7 | 64 | M | NSCLC | T2N3M0 | RLL | Induction | 15 | 19.5 |

| 8 | 72 | F | NSCLC | T2N2M0 | RLL | Induction | 18 | 22.5 |

| 9 | 70 | M | NSCLC | T4N2M0 | RUL | Concurrent | 22 | 19.5 |

| 10 | 52 | M | NSCLC | T4N2M0 | RUL | Induction | 24 | 25.5 |

| 11 | 70 | M | NSCLC | T1N3M0 | RLL | Induction | 20 | 19.5 |

| 12 | 49 | F | NSCLC | T4N0M1 | LLL | Concurrent | 22 | 22.5 |

| 13 | 58 | M | NSCLC | T4N0M0 | RUL | Concurrent | 16 | 25.5 |

| 14 | 45 | M | NSCLC | T4N3M0 | RLL | Concurrent | 15 | 25.5 |

| 15 | 75 | M | SCLC | T4N3M0 | LUL | Concurrent | 15 | 18.0 |

| 16 | 56 | F | SCLC | T4N3M0 | LUL | Concurrent | 14 | 19.5 |

| 17 | 79 | F | NSCLC | T4N0M0 | Mediastinum | No chemo | 15 | 30.6 |

| 18 | 49 | F | NSCLC | T2N2M0 | RUL | Induction | 20 | 34.2 |

| 19 | 58 | F | NSCLC | T3N3M0 | RLL | Induction | 13 | 19.8 |

| 20 | 62 | F | NSCLC | T1N2M0 | RLL | Concurrent | 17 | 16.5 |

| 21 | 75 | M | NSCLC | T2N2M0 | RUL | Concurrent | 11 | 12.0 |

| 22 | 53 | F | NSCLC | T2N3M0 | LUL | Concurrent | 16 | 19.5 |

| 23 | 67 | M | NSCLC | T4N2M0 | LUL | Induction | 18 | 22.5 |

| 24 | 71 | M | NSCLC | T4N2M0 | RLL | Induction | 14 | 16.5 |

| 25 | 65 | M | NSCLC | T1N2M0 | LUL | Induction | 19 | 25.5 |

| 26 | 50 | F | SCLC | T4N2M1 | LUL | Concurrent | 15 | 19.5 |

| 27 | 76 | M | NSCLC | T2N2M0 | RLL | Concurrent | 20 | 25.5 |

| 28 | 61 | M | NSCLC | T4N2Mn.i. | Mediastinum | Induction | 15 | 19.8 |

| 29 | 81 | F | NSCLC | T2N2M0 | RLL | Induction | 19 | 23.4 |

| 30 | 71 | F | NSCLC | T2N2M0 | LLL | Induction | 15 | 16.5 |

| 31 | 63 | M | NSCLC | T4N0M0 | RUL | Induction | 14 | 16.5 |

| 32 | 65 | F | NSCLC | T2N3M0 | RUL | Induction | 21 | 18.0 |

| 33 | 52 | M | NSCLC | T4N2Mn.i. | RUL | Induction | 15 | 23.4 |

| 34 | 60 | M | NSCLC | T1N2M0 | LUL | Concurrent | 16 | 16.5 |

| 35 | 61 | F | SCLC | T4N3M0 | LUL | Concurrent | 17 | 22.5 |

| 36 | 64 | M | NSCLC | T2N3M0 | RUL | Concurrent | 18 | 15.0 |

| 37 | 59 | M | NSCLC | T3N0M0 | RUL | Concurrent | 18 | 16.5 |

| 38* | 64 | M | NSCLC | T1N0M0 | LUL | Concurrent | 20 | 18.0 |

| 39* | 64 | M | NSCLC | T3N2M0 | RUL | Concurrent | 20 | 18.0 |

| 40 | 76 | M | NSCLC | T2N2M0 | LUL | Induction | 16 | 23.4 |

Patient 38* and 39* was a single patient with 2 primary tumors inside the lung; this patient was analyzed separately for every primary tumor.

Dose coverage of the primary tumor

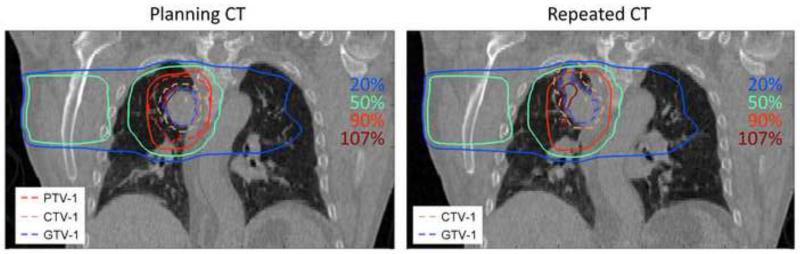

For 38 out of 39 primary tumors the coverage of the CTVprim was 100%. For one patient (2.5%, N=1/39) there was a clear reduction in tumor coverage described by a V90% of 93% and 94% for the bony anatomy and primary tumor match respectively. This loss in tumor coverage was due to tumor growth in cranial direction having an increase in GTV volume of 24% (from 46.4 cm3 to 57.6 cm3). Hence, the treatment fields did not cover the cranial part of the CTV. A coronal slice through the primary tumor is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Example of a patient that had tumor growth in cranial direction. Coverage of this cranial part is not guaranteed by the original treatment plan and cannot be adapted by a bony anatomy or tumor registration based set-up.

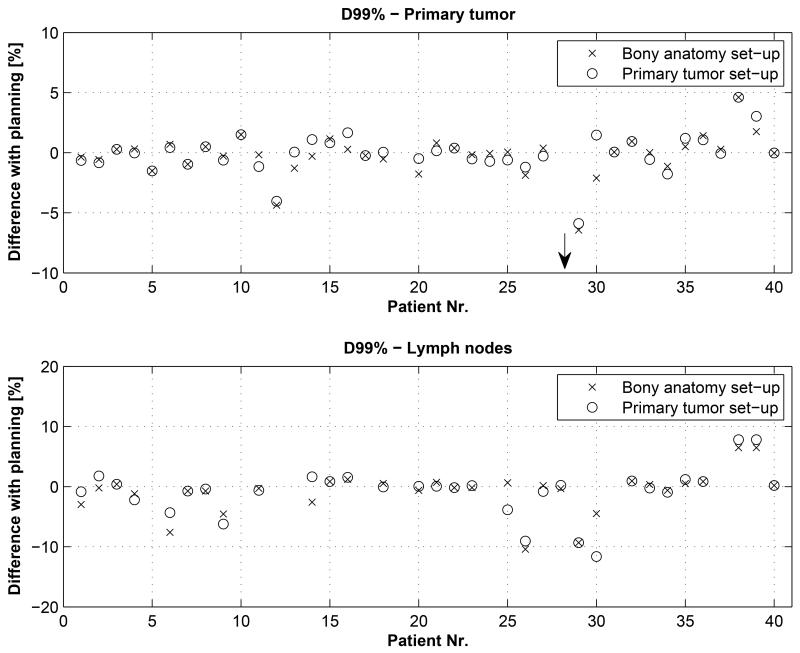

The difference between the D99% of the planned dose and the D99% of the recalculated dose based on the bony anatomy match and the primary tumor match was small, on average −2.0 ± 11.2 (range −69% to +5%, p=0.530) and −1.7% ± 10.6% (range −65% to +5%, p=0.650), see Figure 2. Excluding the patient with tumor growth, these numbers were −0.2 ± 1.7% (range −6.4% to +4.6%, p=0.711) and −0.1% ± 1.7% (range −5.9% to +4.6%, p=0.850). Mean dose inside CTVprim was approximately equal for the bony anatomy and tumor set-up procedure compared to the planned mean dose: 0.1 ± 1.3% (range −2.9% to +4.9%, p=0.738) and 0.2 ± 1.3% (range −2.1% to +4.7%, p=0.989), respectively.

Figure 2.

Differences in minimum dose expressed as the D99% compared to the planning for the primary tumor (top) and lymph nodes (bottom) for patient set-up based on the bony anatomy or primary tumor. The arrow indicates the large dose difference of the patient which had a growth of the primary tumor.

Dose coverage of the lymph nodes

Thirty-one out of 39 patients (79%) had involved mediastinal lymph nodes that were irradiated in the same treatment plan as the primary tumor. The dose coverage (D99%) of the lymph nodes CTVlymph was on average equal to the planned dose for both the bony anatomy and tumor set-up: −0.9±3.6% (range −10% to +6%, p=0.421) and −0.8±4.1% (range −12 to +8%, p=0.499), respectively. The number of patients with a loss in coverage (D99%) larger than 5% was 10% (N=3) for the bony anatomy based set-up and 13% (N=4) for the primary tumor based set-up, see Figure 2. For one patient (3%, N=1) the V90% dropped below 99% for the bony anatomy set-up, and for two patients (6%, N=2) if the primary tumor set-up procedure was chosen. Although in all cases the V90% was still larger than 97%. Mean dose to the CTVlymph did not differ significantly between planning and bony anatomy (p=0.906) or primary tumor (p=0.860) based set-up.

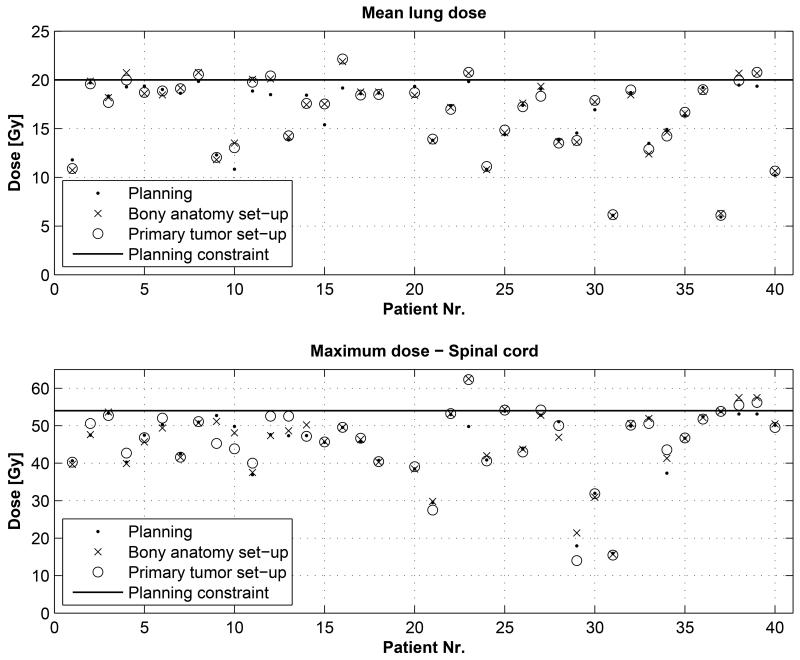

Dose to the normal tissues

The normal tissue constraint that was frequently the dose-limiting factor was the mean lung dose (MLD). The MLD was escalated to a maximum dose of 19±1 Gy. The average MLD during treatment planning was 16.2±3.8 Gy (range 5.9 Gy to 19.8 Gy). The individual values of the MLD are shown in Figure 3. The differences with the bony anatomy based set-up was 1.8±6.4% (range −9 to +25%, p=0.132), and for the primary tumor based set-up the values were 1.7±5.8% (range −8 to +20%, p=0.225). The number of patients with an increase in MLD larger than 5% was 23% (N=9) and 15% (N=6) for the bony anatomy and primary tumor set-up, respectively. 21% (8/39) of the patients exceeded the maximum allowed normal tissue constraint of 20 Gy for the bony anatomy set-up, compared to 13% (5/39) for the primary tumor set-up. The MLD could be up to 22 Gy if the repeated anatomy would persist and the treatment plan would be used for the entire treatment. Four patients (10%) had a reduction in MLD of more than 5% for the bony anatomy based set-up and 2 patients (5%) for the primary tumor set-up.

Figure 3.

Individual patient values for the mean lung dose (top) and maximum spinal cord dose (bottom) of the planned dose, bony anatomy and primary tumor based set-up procedure. The planning constraint is shown as a solid line.

For the spinal cord, the maximum allowed dose expressed as the D0.1% (maximum dose to 0.1% of the volume) was 54 Gy. Maximum dose values are shown in Figure 3 and the average maximum dose was 45.2±9.1 Gy (range 16.0 Gy to 53.9 Gy). The difference with the patient set-up based on bony anatomy and primary tumor was: 1.5±6.0% (range −8% to +28%, p=0.402) and 0.8±7.7% (range −22% to +25%%, p=0.606), respectively. The percentage of patients that received more than 54 Gy was 10% (N=4) for the bony anatomy based set-up and 13% (N=5) for the primary tumor set-up.

Discussion

We analyzed the patient set-up based on two strategies: bony anatomy and primary tumor based set-up. For the primary tumor, there were no differences in the coverage (V90%) of the CTV of the primary tumor for both methods. A single patient showed reduced coverage due to tumor progression that could not be adequately tackled by either the bony anatomy or primary tumor based set-up procedure. For this patient, re-planning needed to be performed to take into account the larger primary tumor volume. For the involved lymph nodes larger differences occurred, although the difference between bony-anatomy and tumor set-up was slightly worse for the tumor-based set-up, around 10% of the patients showed reduced minimum dose levels larger than 5%. For the normal tissue dose, there was a similar trend visible: a small overall increase was observed of around 2%, partly caused by the shrinkage of the primary tumor resulting in more lung volume that is irradiated. Compared to the bony-anatomy based set-up, less patients exceeded the tolerance for the primary tumor based setup, probably due to fact that the primary tumor set-up focuses the beams in the same area as the planning causing a minimum of high dose to the healthy lung around the primary tumor. For the spinal cord, the reverse occurs as the spinal cord is embedded in bony structures, causing fewer deviations for the bony-anatomy set-up compared to the spinal cord set-up as expected.

Repeated imaging during treatment is thus necessary to assess possible dose deviations during treatment. The use of conventional CT imaging allows dose recalculation for the individual patient inside the treatment planning system and therefore assessment of the target coverage but also dose inside the normal tissues. We found that for a subgroup of patients this justified an adaptive treatment procedure. One patient had progressive disease that warranted a re-planning to achieve adequate coverage. Implementing an adaptive procedure to restore the coverage of the nodal target volume could improve 10-15% of the patient treatments; however practical ways of assessing nodal target structures need to be investigated. Deformable image registration methods might be a possibility for this (22). The currently used dose-escalation protocols based on normal tissues push to the target dose up to critical values for normal tissue toxicity, repeated dose calculations show that planning constraints for the normal tissues may be exceeded during treatment for up to 20% of the patients. If non-acceptable normal tissue doses are observed in individual patients, adaptation of the treatment plan may prevent serious toxicities.

In the present study, we used FDG-PET/CT imaging with contrast-enhanced CT as we believe this is at present the best way to perform target delineation for lung cancer patients that includes delineation of the involved mediastinal lymph nodes. With the use of non-contrast enhanced CT or cone-beam CT alone, imaging of the mediastinal nodes is less reliable. The imaging technique during treatment should provide us with comparable image information as the planning CT scan. Therefore, we used the mid-ventilation phase extracted from the 4D CT scan as the preferred imaging technique to be compared to the planning 4D CT scan. The use of a 3D CT either in the planning phase or during treatment might introduce additional errors because the tumor might be captured in one of the extreme positions which is not representative for the actual treatment. Obviously new techniques like e.g. contrast-enhanced cone-beam CT imaging (23) or an integrated MRI with a linear accelerator(24) might be options that also need to be explored for this.

Previous studies have shown that surrogates for time-trends in nodal volume or baseline shifts are difficult, if not impossible, to obtain from primary tumor characteristics (9, 11-13). Hence, one has to be careful by adapting a treatment of the nodal volumes based on primary tumor characteristics. We therefore investigated in this study the influence of the patient set-up procedure. On average only moderate differences were observed for the lymph nodes, partly explained by the fact that the treatment plans were 3D conformal. The current more and more used intensity modulated radiotherapy treatment (IMRT) techniques allow for even more conformal dose distributions to the target volumes with as a consequence that a shift of the dose distribution might have more impact on the coverage compared to the less conformal 3D dose distributions.

Based on the results of this study it was shown that choosing either a primary tumor set-up method or a bony-anatomy set-up is not suitable for every individual patient, high-quality repeated imaging needs to be performed during treatment to assess the impact of dosimetric changes during treatment. We are currently implementing a protocol for all our lung cancer patients treated with a radical treatment to obtain a second FDG-PET CT scan during treatment to guarantee accuracy of treatment and if necessary adapt the treatment plan to reach the intended dose coverage of target volumes and prevent overdosage of the normal tissues.

Conclusion

Repeated imaging during treatment is useful to detect tumor progression that may lead to reduced target coverage. In 10 to 13% of the patients that had nodal involvement, set-up based on bony anatomy or primary tumor lead to important dose deviations in the involved lymph nodes, respectively. Bony anatomy or primary tumor based set-up procedures therefore do not guarantee correct dose delivery to the involved lymph nodes for all patients. The development of practical ways for repeated imaging of all tumor sites during radiotherapy should therefore be an important research focus.

Acknowledgement

This study was performed within the framework of CTMM, the Center for Translational Molecular Medicine (www.ctmm.nl), project AIRFORCE number 03O-103.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none

References

- 1.Belderbos JS, Heemsbergen WD, De Jaeger K, et al. Final results of a Phase I/II dose escalation trial in non-small-cell lung cancer using three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Baardwijk A, Wanders S, Boersma L, et al. Mature results of an individualized radiation dose prescription study based on normal tissue constraints in stages I to III non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1380–1386. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.7221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Ruysscher D, Wanders S, van Haren E, et al. Selective mediastinal node irradiation based on FDG-PET scan data in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: a prospective clinical study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62:988–994. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosmans G, van Baardwijk A, Dekker A, et al. Intra-patient variability of tumor volume and tumor motion during conventionally fractionated radiotherapy for locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a prospective clinical study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:748–753. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox J, Ford E, Redmond K, et al. Quantification of tumor volume changes during radiotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:341–348. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.07.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kupelian PA, Ramsey C, Meeks SL, et al. Serial megavoltage CT imaging during external beam radiotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer: observations on tumor regression during treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:1024–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siker ML, Tome WA, Mehta MP. Tumor volume changes on serial imaging with megavoltage CT for non-small-cell lung cancer during intensity-modulated radiotherapy: how reliable, consistent, and meaningful is the effect? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang J, Mageras GS, Yorke E, et al. Observation of interfractional variations in lung tumor position using respiratory gated and ungated megavoltage cone-beam computed tomography. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67:1548–1558. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.11.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sonke JJ, Lebesque J, van Herk M. Variability of four-dimensional computed tomography patient models. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:590–598. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Underberg RW, Lagerwaard FJ, van Tinteren H, et al. Time trends in target volumes for stage I non-small-cell lung cancer after stereotactic radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:1221–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pantarotto JR, Piet AH, Vincent A, et al. Motion analysis of 100 mediastinal lymph nodes: potential pitfalls in treatment planning and adaptive strategies. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:1092–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bosmans G, van Baardwijk A, Dekker A, et al. Time trends in nodal volumes and motion during radiotherapy for patients with stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71:139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.08.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Elmpt W, Öllers M, van Herwijnen H, et al. Volume or position changes of the primary lung tumor during (chemo-)radiotherapy cannot be used as a surrogate for the mediastinal lymph node changes: The case for optimal mediastinal lymph node imaging during radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steenbakkers RJ, Duppen JC, Fitton I, et al. Reduction of observer variation using matched CT-PET for lung cancer delineation: a three-dimensional analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:435–448. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Baardwijk A, Bosmans G, Boersma L, et al. PET-CT-based auto-contouring in non-small-cell lung cancer correlates with pathology and reduces interobserver variability in the delineation of the primary tumor and involved nodal volumes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68:771–778. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Herk M. Different styles of image-guided radiotherapy. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2007;17:258–267. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Loon J, De Ruysscher D, Wanders R, et al. Selective Nodal Irradiation on Basis of (18)FDG-PET Scans in Limited-Disease Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Prospective Study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.04.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Baardwijk A, Bosmans G, Bentzen SM, et al. Radiation dose prescription for non-small-cell lung cancer according to normal tissue dose constraints: an in silico clinical trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71:1103–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Baardwijk A, Bosmans G, Boersma L, et al. Individualized radical radiotherapy of non-small-cell lung cancer based on normal tissue dose constraints: a feasibility study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71:1394–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.11.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stroom JC, de Boer HC, Huizenga H, et al. Inclusion of geometrical uncertainties in radiotherapy treatment planning by means of coverage probability. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;43:905–919. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00468-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Herk M, Remeijer P, Rasch C, et al. The probability of correct target dosage: dose-population histograms for deriving treatment margins in radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47:1121–1135. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00518-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sonke JJ, Belderbos J. Adaptive radiotherapy for lung cancer. Semin Radiat Oncol. 20:94–106. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tse RV, Moseley DJ, Siewerdsen J, et al. Intrahepatic Tumor and Vessel Identification in Intravenous Contrast Enhanced Liver kV Cone Beam CT. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:S666–S667. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lagendijk JJ, Raaymakers BW, Raaijmakers AJ, et al. MRI/linac integration. Radiother Oncol. 2008;86:25–29. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]