Abstract

TonB systems actively transport iron-bound substrates across the outer membranes of Gram-negative bacteria. Vibrio vulnificus CMCP6, which causes fatal septicemia and necrotizing wound infections, possesses three active TonB systems. It is not known why V. vulnificus CMCP6 has maintained three TonB systems throughout its evolution. The TonB1 and TonB2 systems are relatively well characterized, while the pathophysiological function of the TonB3 system is still elusive. A reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) study showed that the tonB1 and tonB2 genes are preferentially induced in vivo, whereas tonB3 is persistently transcribed, albeit at low expression levels, under both in vitro and in vivo conditions. The goal of the present study was to elucidate the raison d'être of these three TonB systems. In contrast to previous studies, we constructed in-frame single-, double-, and triple-deletion mutants of the entire structural genes in TonB loci, and the changes in various virulence-related phenotypes were evaluated. Surprisingly, only the tonB123 mutant exhibited a significant delay in killing eukaryotic cells, which was complemented in trans with any TonB operon. Very interestingly, we discovered that flagellum biogenesis was defective in the tonB123 mutant. The loss of flagellation contributed to severe defects in motility and adhesion of the mutant. Because of the difficulty of making contact with host cells, the mutant manifested defective RtxA1 toxin production, which resulted in impaired invasiveness, delayed cytotoxicity, and decreased lethality for mice. Taken together, these results indicate that a series of virulence defects in all three TonB systems of V. vulnificus CMCP6 coordinately complement each other for iron assimilation and full virulence expression by ensuring flagellar biogenesis.

INTRODUCTION

Vibrio vulnificus is a halophilic estuarine pathogen that causes fatal septicemia and necrotizing wound infections in patients suffering from hepatic diseases with high levels of circulating iron or who are immunocompromised (1–5). Infection with V. vulnificus typically shows rapid progression and mortality rates greater than 50% (6, 7). In Gram-negative bacteria, the inner membrane protein complex TonB plays a crucial role in the uptake of iron (8, 9), which is an important micronutrient for numerous biological processes (10–12). TonB complexes transduce the proton motive force (PMF) of the cytoplasmic membrane to energize iron-siderophore complex transport through a specific TonB-dependent transporter (TBDT) across the outer membrane (OM) (9, 13, 14). This system's known biological roles had been restricted to iron complexes (15, 16) and vitamin B12 (14), but recent experimental evidence of the TonB-energized transport of nickel and various carbohydrates suggests that the number and variety of TonB-dependent substrates have been underestimated (17–19). Unlike the single TonB system in Escherichia coli (8), the genomes of Vibrio species carry multiple TonB systems. Interestingly, three TonB systems were first reported in V. vulnificus CMCP6 by the late Jorge Crosa's team (20). As a result of the pivotal findings of Crosa's group, the importance of TonB1 and TonB2 systems in the iron transport of siderophores and in the pathogenesis of V. vulnificus has been highlighted (20, 21). Also, they reported that the functionally elusive TonB3 has a unique regulation mechanism consisting of Lrp (l-leucine responsive protein) and CRP (cAMP receptor protein) (20, 22). Based upon the regulation of TonB3 system by Lrp and CRP, they proposed that TonB3 would function to integrate different environmental signals such as glucose starvation and the transition between “feast” and “famine.” However, the pathophysiological function of TonB3 remains poorly defined. Our preliminary real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) experiments demonstrated that while the tonB1 and tonB2 systems are highly expressed in vivo, tonB3 is persistently transcribed, albeit at low expression levels, under in vitro and in vivo conditions. This result prompted us to study why V. vulnificus CMCP6 has maintained three TonB systems throughout the long path of evolution. In previous studies performed by Crosa's group, they used in-frame deletion mutants of the structural tonB genes with in trans complementation. Since the three TonB systems share similarly functioning genes, single-gene-mutation studies might not rule out the interaction among remaining genes in the same operon and the tonB genes in other TonB operons. Hence, in this study, we constructed mutants with single and multiple deletions of the entire structural genes in TonB loci and complemented them with cosmid clones harboring each operon to evaluate the pathogenic significance of these TonB systems in V. vulnificus. Through a variety of experimental approaches, we demonstrated that all three TonB systems appear to coordinately complement each other for flagellum biogenesis and full virulence expression of V. vulnificus CMCP6 in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media.

The V. vulnificus strains, E. coli strains, and plasmids that were used in this study are listed in Table 1. The wild-type V. vulnificus strain was CMCP6, a highly virulent clinical isolate whose genome sequence was recently reannotated for higher accuracy (23, 24). E. coli and V. vulnificus were grown in Luria-Bertani and 2.5% NaCl heart infusion (HI) media, respectively. Antibiotics were used as previously described (25).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| V. vulnificus | ||

| CMCP6 | Wild type, clinical isolate | CNU Hospital |

| ΔtonB1 | CMCP6 with in-frame deletion of entire structural genes in TonB1 locus | This study |

| ΔtonB2 | CMCP6 with in-frame deletion of entire structural genes in TonB2 locus | This study |

| ΔtonB3 | CMCP6 with in-frame deletion of entire structural genes in TonB3 locus | This study |

| ΔtonB12 | CMCP6 with in-frame double deletion of entire structural genes in TonB12 loci | This study |

| ΔtonB13 | CMCP6 with in-frame double deletion of entire structural genes in TonB13 loci | This study |

| ΔtonB23 | CMCP6 with in-frame double deletion of entire structural genes in TonB23 loci | This study |

| ΔtonB123 | CMCP6 with in-frame triple deletion of entire structural genes in TonB123 loci | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | F− recA1 restriction negative | Laboratory collection |

| SY327 λ pir | Δ(lac pro) argE(Am) rif nalA recA56 λ pir lysogen | 26 |

| SM10 λ pir | thi thr leu tonA lacY supE recA::RP4-2-Tcr::Mu Kmr λ pir lysogen | 26 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pDM4 | Suicide vector with ori R6K sacB; Cmr | 58 |

| pLAFR3 | IncP cosmid vector; Tcr | 59 |

| pRK2013 | IncP Kmr Tra Rk2+ repRK2 repE1 | 60 |

| pCMM1509 | pDM4 with a 2-kb SacI/SpeI in-frame deleted tonB1 operon | This study |

| pCMM1510 | pDM4 with a 2-kb SacI/SpeI in-frame deleted tonB2 operon | This study |

| pCMM1511 | pDM4 with a 1.9-kb SacI/SmaI in-frame deleted tonB3 operon | This study |

| pCMM1512 | pLAFR3 with a 25-kb fragment containing the in-frame deleted tonB1 operon | This study |

| pCMM1513 | pLAFR3 with a 25-kb fragment containing the in-frame deleted tonB2 operon | This study |

| pCMM1514 | pLAFR3 with a 25-kb fragment containing the in-frame deleted tonB3 operon | This study |

Cmr, Cm resistance; Tcr, Tc resistance; Apr, Ap resistance; Kmr, Km resistance.

Construction of deletion mutants and complementation.

We constructed in-frame single, double, and triple deletion mutants of the entire structural genes in TonB1, TonB2, and TonB3 loci by the allelic-exchange method using the suicide vector pDM4 (26). For each TonB system, we designed two sets of primers to amplify DNA fragments in the upstream or downstream region of each operon. The sequences of each primer pair are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Some primer sets included restriction site overhangs that were recognized by specific restriction enzymes for cloning. The upstream and downstream amplicons of each TonB operon were ligated by crossover PCR to produce a 2-kb fragment (27). The fusion fragments were digested with the appropriate enzymes and subcloned into pDM4 for the tonB1, tonB2, and tonB3 mutants, yielding pCMM1509, pCMM1510, and pCMM1511, respectively. All of the resulting recombinant pDM4 plasmids were transferred into V. vulnificus CMCP6 by conjugation, and the single-deletion mutants (ΔtonB1, ΔtonB2, and ΔtonB3 mutants) were selected as previously described (28). The tonB12 and tonB13 double mutants (ΔtonB12 and ΔtonB13 mutants) were constructed by transferring pCMM1509 into the ΔtonB2 and ΔtonB3 mutants, respectively. The tonB23 double and tonB123 triple mutants (ΔtonB23 and ΔtonB123 mutants) were constructed by transferring pCMM1511 into the ΔtonB2 and ΔtonB12 mutants, respectively. For genetic complementation experiments, we screened cosmid clones that contained an intact tonB1, tonB2, or tonB3 operon from the pLAFR3 cosmid library of V. vulnificus CMCP6 as previously described (29), yielding pCMM1512 (ptonB1), pCMM1513 (ptonB2), and pCMM1514 (ptonB3), respectively. The positive colony was transferred to deletion mutants by triparental mating with the conjugative helper plasmid pRK2013. The transconjugants were selected as previously described (29).

Cytotoxicity assay.

To determine the effect of TonB mutations on cytotoxicity for HeLa cells, we performed the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay as previously described (30).

LD50 determination.

The intraperitoneal 50% lethal doses (i.p. LD50) of V. vulnificus were determined using normal and iron-overloaded mice as previously described (30). Briefly, for the iron-overloading experiment, groups of 7-week-old randomly bred specific-pathogen-free (SPF) female CD-1 mice (Daehan Animal Co., Daejeon, South Korea) were i.p. injected with 900 μg of ferric ammonium citrate (filter sterilized; 100 μg of elemental iron) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 min before bacterial challenge. Five mice per group were administered 10-fold serial dilutions of fresh bacterial suspensions, and the infected mice were observed for 48 h. The intragastric 50% lethal dose (i.g. LD50) was tested using randomly bred SPF CD-1 suckling mice (Daehan Animal Co., Daejeon, South Korea). Six-day-old infant mice were administered 10-fold serial dilutions of fresh bacterial suspensions containing 0.1% Evans blue (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO) to ensure correct i.g. administration. The control animals received 100 μl of PBS containing 0.1% Evans blue. The challenged mice were monitored for 48 h. Seven mice per group were used for analysis. LD50 was calculated by the probit analysis, using IBM SPSS 21.0 software (IBM). All of the animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committee of Chonnam National University, South Korea.

In vivo invasion assay.

The bacterial cells that translocated from the intestine to the bloodstream were measured as previously described (31, 32). Seven-week-old SPF female CD-1 mice were starved for 16 h and anesthetized with a mixture of 10% zolazepam-tiletamine (Zoletil; Virbac Laboratories, France) and 5% xylazine (Rumpun; Byer Korea, South Korea) dissolved in PBS. The ileum was tied off in a 5-cm segment, and then V. vulnificus cells (4.0 × 106 CFU/400 μl in PBS) were inoculated into the ligated segment. The blood samples were acquired by cardiac puncture at various time intervals. Viable bacterial cells were counted by plating on 2.5% NaCl HI agar plates. Remaining V. vulnificus cells in ligated ileal loops were also counted by plating on Vibrio-selective thiosulfate-citrate-bile salts-sucrose (TCBS) agar plates.

In vitro invasion assay.

Polarized HCA-7 cells grown on Transwell filter chambers (8-μm pore size; Costar, Cambridge, MA, USA) were apically exposed to log-phase V. vulnificus cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5 under serum-free conditions. The invasiveness was determined by measuring the change in transepithelial electrical resistance (33) and the number of bacterial cells that translocated from the upper chamber to the lower chamber of the Transwell (32). Viable bacterial cells were counted by plating on 2.5% NaCl HI agar plates. LDH release from polarized HCA-7 cells was measured in culture media collected from the upper and lower chambers of the Transwells using the CytoTox nonradioactive cytotoxicity assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

Growth of the bacteria in the rat peritoneal cavity and mouse blood.

The in vivo growth of V. vulnificus was measured using a dialysis tube implantation model. CelluSep H1 dialysis tubing (molecular weight cutoff [MWCO], ∼12,000 to 14,000; Membrane Filtration Products, Inc., TX, USA) was incubated with PBS overnight. The dialysis membrane was disinfected with 70% alcohol for 1 h and washed three times with sterile PBS before use. Seven-week-old female Sprague Dawley (SD) rats (DBL Co. Ltd., Daejeon, South Korea) were anesthetized with a mixture of 10% zolazepam-tiletamine and 5% xylazine dissolved in PBS. Three 10-cm dialysis tubes that contained 2 ml of 5 × 105 CFU/ml V. vulnificus cells were surgically implanted into the rat peritoneal cavity. The bacterial growth at each time point was analyzed using three rats. The bacteria were harvested for viable-cell counting on 2.5% NaCl HI agar plates after 2, 4, and 6 h of implantation.

For growth in blood, each mouse was intravenously injected with 100 μl of 5 × 105 CFU cells which had been incubated in the rat peritoneal cavity for 6 h for in vivo adaptation. After various times, blood samples were acquired from infected mice by cardiac puncture. Viable bacterial cells were counted by plating on 2.5% NaCl HI agar plates.

Host cell adhesion assay.

For the adhesion assay, HeLa cell monolayers were seeded on chamber slides (Nunc) and then infected with log-phase V. vulnificus cells at an MOI of 250 for 30 min. The monolayer was then washed twice with PBS to remove nonadherent bacteria. Following the last wash, cells were fixed in methanol and stained with 0.1% Giemsa (Sigma). The V. vulnificus cells that adhered to HeLa cells were enumerated and examined under a light microscope at magnifications of ×400 and ×1,000 (Eclipse 50i; Nikon, Japan).

Motility assay.

For motility assays, 1 μl of 1 × 109 CFU/ml log-phase V. vulnificus cells was inoculated on motility assay agar (0.3% agar–2.5% NaCl HI plate) and incubated at 37°C. Zones of migration were observed after 12 h.

Electron microscopy.

V. vulnificus strains were grown to mid-log phase in 2.5% NaCl HI broth without agitation. The V. vulnificus cells were fixed in a fixation solution containing 0.1% glutaraldehyde and 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.05 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) at room temperature for 4 h. After three washes with 0.05 M cacodylate buffer, all samples were mounted on nickel grids coated with carbon film (150 mesh). After staining with 2% uranyl acetate, the samples were examined with a transmission electron microscope (JEM-1400; JEOL Ltd., Japan) at 80-kV acceleration. The morphological differences of bacterial strains were observed at a magnification of ×25,000.

Conventional and real-time RT-PCR.

Transcription of the three structural tonB systems was determined by conventional and real-time RT-PCR. The 16S rRNA was used as the internal standard for conventional RT-PCR, and gyrA was chosen as a suitable reference gene for real-time RT-PCR, since the expression level was consistent under different experimental conditions (in vivo and in vitro), and it has amplification efficiencies comparable to those of the target tonB genes. Forward and reverse primer pairs were designed as shown in Table S2 in the supplemental material. The total RNA was isolated from log-phase bacterial cells that had been cultured in the rat peritoneal cavity or in 2.5% NaCl HI broth using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany). One microgram of purified RNA was converted to cDNA using the QuantiTect reverse transcription kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and 3 μg of RNA was used to evaluate tonB3 expression. Real-time RT-PCR was performed to quantify each target transcript using the QuantiTect SYBR green PCR kit (Qiagen). The relative gene expression was normalized to the expression of gyrA (34) using the threshold cycle (ΔΔCT) method (35). Simultaneously, conventional RT-PCR was performed, and the amplicons were separated on 2% (wt/vol) agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide. Additionally, transcription of rtxA1 was also examined by conventional RT-PCR using the HeLa cell infection model. Log-phase V. vulnificus cells were exposed to HeLa cells for 30, 60, and 90 min. At various time points, the bacterial cells attached to the HeLa cells were scraped off, and total RNA was isolated as described above.

Western blot analysis.

For RtxA1 detection, HeLa cells grown on 6-well plates were infected with V. vulnificus log-phase cells at an MOI of 100 under the serum-free conditions. After 30, 60, and 90 min of incubation, the bacterial cells attached to HeLa cells were lysed with lysis buffer (Cell Signaling) and concentrated with an Amicon Ultra-0.5 centrifugal filter (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). The samples were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE. The RtxA1 proteins were detected using an anti-C-terminal GD-rich domain (anti-GD domain) antibody (RtxA1-C, a band of approximately 130 kDa) (36). For the Western blot analysis of FlaB, bacteria were cultured in 2.5% NaCl HI to log-phase growth, and then FlaB proteins in the bacterial cell pellet or the culture supernatant were detected using an anti-FlaB antibody (a band of approximately 42 kDa) as described previously (32).

Outer membrane protein purification.

Changes in the outer membrane protein (OMP) profile of the mutant were tested. OMPs were purified by a method reported elsewhere (37). The OMP preparations were analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE. The OMP bands showing differential expression between the wild-type and mutant were further identified by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight (MALDI-TOF MS).

DNA alignment.

A Fur box was identified first in E. coli as a 19-bp palindromic sequence accommodating a Fur dimer (38). This Fur-binding motif is strictly conserved in other bacteria, including Vibrio cholerae, Yersinia pestis, and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, based on motif alignments of 5′ untranslated regions (UTRs) of Fur-regulated genes (39–41). This allowed us to use the same profile for the recognition of Fur boxes in the promoter regions of flagellin genes (GATAATGATAATCATTATC). Multiple DNA alignments were constructed using CLUSTALX (42).

Statistical analysis.

The results are expressed as means and standard errors of the means (SEM) unless otherwise stated. Each experiment was repeated a minimum of three times, and the results from representative samples are shown. Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 5.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Multiple comparisons were performed using Student's t test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni post hoc tests. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The structural tonB1 and tonB2 genes are significantly induced in vivo, whereas tonB3 is persistently transcribed at low levels under in vitro and in vivo conditions.

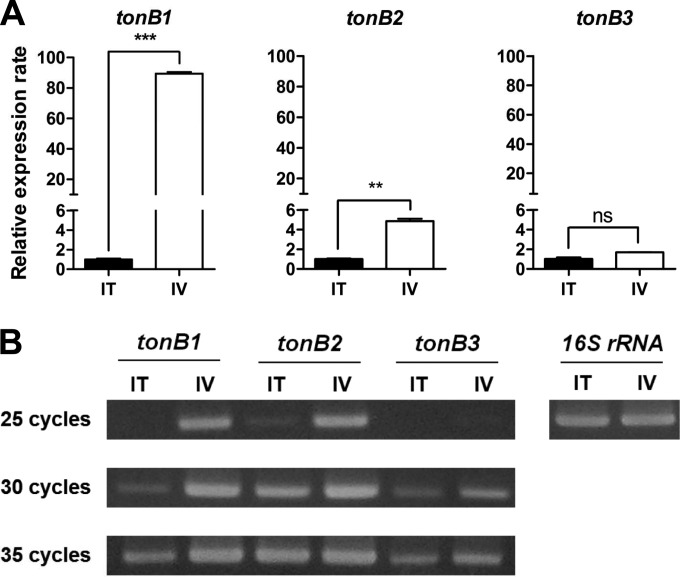

Many important virulence genes of pathogenic bacteria are preferentially expressed in vivo (28, 43, 44). To see whether host signals could induce the transcription of three TonB systems of V. vulnificus CMCP6 during the infection process, we compared transcription levels of three structural tonB genes under in vitro and in vivo culture conditions by conventional and real-time RT-PCR (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). According to real-time RT-PCR results, higher levels of tonB1 and tonB2 mRNAs were observed under in vivo conditions than in vitro conditions, with approximately 90- and 5-fold changes, respectively (Fig. 1A) (P < 0.001 for tonB1 and P < 0.01 for tonB2). Interestingly, low levels of transcripts of tonB3 were obtained under both conditions using 3-fold more total RNA (3 μg) than for assessing tonB1 and tonB2 (1 μg). The comparable transcription levels of the tonB3 gene by the real-time RT-PCR under both conditions indicated that this system would be persistently transcribed irrespective of the culture environment, albeit at a low expression level (Fig. 1A) (P > 0.05). The expression of three structural tonB genes was further confirmed through conventional RT-PCR with different amplification cycles. In agreement with the real-time PCR results, we detected significantly increased expression of tonB1 and tonB2 under in vivo conditions, whereas the expression of tonB3 was detected only in late cycles under both conditions (Fig. 1B). These findings led us to hypothesize that all three TonB systems would be functional, which drove us to further investigate the role of three TonB systems in the pathogenesis of V. vulnificus CMCP6 infections.

FIG 1.

Transcription levels of the three structural tonB genes in V. vulnificus CMCP6. The transcription levels of the three structural tonB genes were analyzed by real-time (A) and conventional (B) RT-PCR under in vitro and in vivo conditions. RNA was isolated from the log-phase bacterial cells that had been cultured in the rat peritoneal cavity (in vivo [IV]) or in 2.5% NaCl HI broth (in vitro [IT]) and then converted to cDNA. qRT-PCR was performed, and the data were normalized to expression of the housekeeping gene gyrA. The values for the relative transcript abundance were expressed as mean-normalized gene expression relative to the in vitro expression values. The results showed that tonB1 and tonB2 genes are significantly induced in vivo, whereas tonB3 is persistently transcribed at low levels under both tested conditions. The error bars represent the standard errors of means from three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was carried out using Student's t test (**, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ns, not significant).

Cytotoxicity was delayed only in the tonB123 triple mutant and was significantly recovered by complementation with each TonB system.

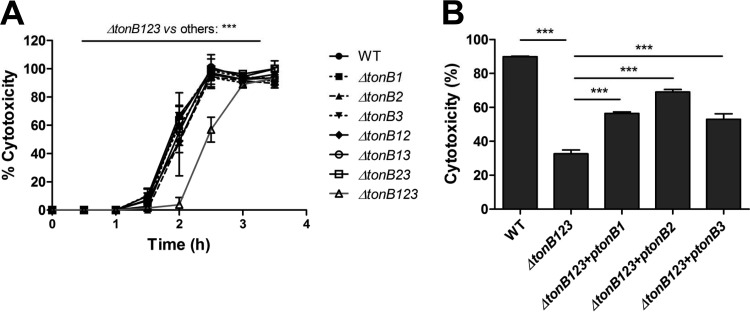

To evaluate the pathogenic significance of three TonB systems in V. vulnificus, in-frame single (ΔtonB1, ΔtonB2, and ΔtonB3), double (ΔtonB12, ΔtonB13, and ΔtonB23), and triple (ΔtonB123) deletion mutants were constructed (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The cytotoxicity of V. vulnificus was measured in a time course. Interestingly, only the ΔtonB123 mutant exhibited significantly delayed cytotoxicity, whereas the single and double mutants showed little or no changes during 3.5 h of the assay (Fig. 2A) (P < 0.001). The cytotoxicity of the ΔtonB123 mutant approached the wild-type level after 3 h of incubation (Fig. 2A). Full cytotoxic expression was delayed by 30 min in the ΔtonB123 mutant compared to the wild-type strain.

FIG 2.

Significantly delayed cytotoxicity for HeLa cells in the tonB123 triple mutant (A) and the complemented strain (B). (A) Log-phase V. vulnificus cells were incubated with HeLa cells at an MOI of 100. Statistical analysis of the tonB123 mutant using two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc tests revealed significantly delayed cytotoxicity for HeLa cells in comparison with the wild type and other mutant strains (***, P < 0.001). (B) Restoration of the cytotoxicity in the TonB-complemented strains at 2.5 h. The values are means plus SEM from three independent experiments that were performed in six replicates. Comparisons were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni post hoc tests on the data in panel B (***, P < 0.001). WT, wild type.

In an attempt to fulfill the molecular Koch's postulates, we performed a complementation study. We first selected cosmid clones that contain an intact TonB1, TonB2, or TonB3 operon by screening of a pLAFR3 cosmid library of V. vulnificus CMCP6 as previously described (29). The ΔtonB123 mutation was separately complemented with the individual cosmid clone harboring each TonB operon. The restoration of expression of each TonB operon was confirmed in the TonB-complemented strains by RT-PCR (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). The ΔtonB123 mutant significantly recovered cytotoxicity when complemented with any one of the three TonB operons (Fig. 2B) (P < 0.001). Interestingly, complementation with the TonB2 operon restored most the cytotoxicity, while TonB1 and TonB3 complementation showed levels of cytotoxicity comparable to each other. This result suggests that the TonB2 system plays a dominant role as reported previously (20, 21) compared to the other two systems and that TonB3 is as efficient as the TonB1 in the complementation of the tonB123 mutation. The cytotoxicity defect of the ΔtonB123 mutant could have resulted from a possible bacterial growth retardation in the cell culture medium. To ascertain this possibility, we also checked growth profiles of V. vulnificus strains in high-glucose DMEM, which was used for cytotoxicity assays (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The growth profile of the ΔtonB123 mutant was identical to that of the wild-type strain, suggesting that the growth difference was not the cause of cytotoxicity impairment. Based upon these results, we hypothesized that another specific virulence factor(s) related to cytotoxicity was affected by the tonB123 mutation.

All three TonB systems contribute to V. vulnificus lethality for mice.

To examine the contribution of three TonB systems to the mouse lethality, the i.g. LD50 was measured using 6-day-old suckling mice. As shown in Table 2, a complete deficiency of TonB function (ΔtonB123) resulted in a 42-fold increase in the i.g. LD50 compared with that of the wild-type strain. Significantly prolonged survival was observed in the groups given the ΔtonB123 strain at all infection dosages (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material) (P < 0.05 at 109, 107, and 106 CFU/mouse, and P < 0.01 at 108 CFU/mouse, by Kaplan-Meier survival analysis). At doses of 109 CFU/mouse, all mice infected with the wild-type strain died, whereas only ca. 30% of infected mice died in the group receiving the ΔtonB123 strain by 12 h postinfection (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material) (P < 0.05, log rank test). Together, the results highlight the idea that all three TonB systems contribute to the in vivo virulence expression of V. vulnificus CMCP6.

TABLE 2.

Effect of the mutation of all three TonB systems on the lethality to mice

| Infection and mouse type | LD50 (95% confidence limits) |

Fold increase | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | ΔtonB123 mutant | ||

| Intragastric | |||

| Suckling | 1.26 × 105 (2.16 × 104 to 4.82 × 105) | 5.23 × 106 (3.32 × 105 to 9.95 × 107) | 41.62 |

| Intraperitoneal | |||

| Normal | 3.15 × 105 (8.38 × 104 to 1.13 × 106) | 8.12 × 106 (2.04 × 106 to 3.1 × 107) | 25.78 |

| Iron overloaded | 2.125 | 2.125 | 1 |

In addition to the i.g. infection, we also measured the i.p. LD50 in normal and iron-overloaded mice. The i.p. LD50 of the ΔtonB123 mutant increased 26-fold in normal mice, whereas no change was noted in iron-overloaded mice (Table 2). It was interesting that the lethality of the ΔtonB123 mutant for mice was as strong as that of the parental wild-type strain in hosts having high levels of iron. These results imply that the three TonB systems play an important role in acquiring iron under iron-limited rather than iron-sufficient conditions. The difference in LD50 between the ΔtonB123 and wild-type strains was smaller in the i.p. infection model (26-fold) than the i.g. infection model (42-fold). Since the i.g. infection route simulates more physiologically the primary V. vulnificus septicemia infection process in humans, the three TonB systems might significantly contribute to the virulence factor expression or survival of V. vulnificus CMCP6 during the early invasion phase of primary infection. In this context, we next tested the tissue invasiveness of the ΔtonB123 mutant.

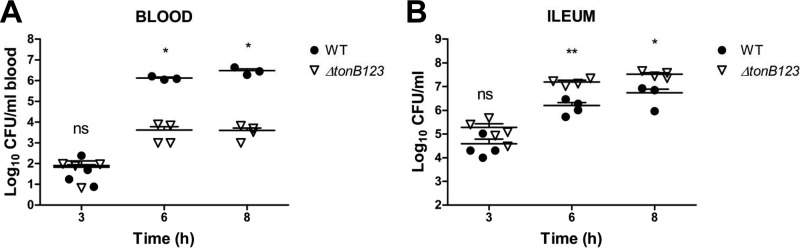

All three TonB systems contribute to the intestinal invasion of V. vulnificus.

To corroborate whether the three TonB systems contribute to the invasiveness of V. vulnificus CMCP6, we performed an in vivo invasion assay using the mouse ligated-ileal-loop infection model (32). Viable V. vulnificus cells in the blood were counted at 3, 6, and 8 h to evaluate the tissue invasiveness of the ΔtonB123 mutant. At 3 h, both strains were discovered in blood circulation at comparable numbers (Fig. 3A) (P > 0.05). Significantly higher numbers of wild-type cells were counted at later time points, approximately 1.3 × 106 and 3.0 × 106 CFU/ml of wild-type cells at 6 h and 8 h, respectively (Fig. 3A) (P < 0.05). During these experiments, we found that 40% of the infected wild-type mice succumbed to the infection when the cell counts reached approximately 1 × 107 CFU/ml of blood (data not shown). In contrast, the defects of the ΔtonB123 mutant resulted in a significant decrease in the translocation of V. vulnificus from the intestinal tract into the bloodstream; only ca. 4.0 × 103 CFU/ml of the ΔtonB123 cells were detected in the bloodstream even at 6 and 8 h (Fig. 3A) (P < 0.05 compared to that of the wild-type strain).

FIG 3.

Impaired transepithelial invasion of the tonB123 triple mutant. V. vulnificus (4.0 × 106 CFU/400 μl) was inoculated into ligated ileal loops of mice under anesthesia. (A) After the indicated times, blood samples were acquired from infected mice by cardiac puncture. Viable cells were counted by plating on 2.5% NaCl HI agar plates. (B) The remaining V. vulnificus cells in ligated ileal loops were also counted by plating on TCBS agar plates. The data are averages and SEM for at least three mice, and the experiment was repeated three times. Statistical analysis was carried out using Student's t test (*, P < 0.05, and **, P < 0.01, compared to the wild-type strain).

In parallel with viable cells in the blood, we also counted bacterial cells in the ileum at various time points. At 3 h, we also detected comparable numbers of V. vulnificus in the ileum in both strains (Fig. 3B) (P > 0.05). However, the viable-cell count of the ΔtonB123 mutant was significantly higher than that of the wild-type strain at later time points (Fig. 3B) (P < 0.01 at 6 h and P < 0.05 at 8 h). The nonfunctional TonB systems in the ΔtonB123 mutant seemed to have no influence on growth in the ileum, since the viable-cell count steadily increased up to 1.0 × 107 CFU/ml in a time course. To confirm further that the attenuated invasion property of the mutant was due to the growth retardation, we checked in vivo growth using the peritoneal dialysis tube implantation model and the growth in mouse blood. The growth profiles of the wild-type and the ΔtonB123 mutant were identical in the dialysis tubes implanted in the rat peritoneum (see Fig. S4B [panel a] in the supplemental material). We also observed a similar pattern of viable-cell counts of both strains in the mouse blood, a rapidly decreasing curve over time, since viable bacteria were removed, presumably by a multitude of host defense mechanisms, such as complement-mediated lysis, phagocytosis, and antimicrobial peptide-mediated killing (see Fig. S4B [panel b] in the supplemental material). In this study, we could not observe significant differences in viable-cell counts in two different models, the culture in peritoneally implanted dialysis tubes filled with PBS (see Fig. S4B [panel a] in the supplemental material) and viable bacterial counting in the bloodstream (see Fig. S4B [panel b] in the supplemental material). Of note, the three TonB systems appeared to be dispensable for growth of V. vulnificus CMCP6 even in normal animals having intact iron-withholding ability. However, they appeared to play a significant role in providing invasive competence to V. vulnificus growing in the host environment. Taken together, these results support our hypothesis that the impaired transepithelial invasion of the ΔtonB123 mutant is responsible for the incompetent intragastric infection by this strain.

A complete functional deficiency of tonB123 significantly attenuated in vitro translocation across polarized intestinal epithelial monolayers.

The invasiveness of V. vulnificus strains was further assessed using an in vitro intestinal epithelial barrier system. Polarized HCA-7 cells grown on Transwell filters were apically infected with V. vulnificus at an MOI of 5 under serum-free conditions. The change in transepithelial resistance (TER), which represents the tight junction disruption by bacterial infection, was measured. As shown in Fig. 4A, the TER gradually decreased after wild-type infection, whereas a significant delay was observed in HCA-7 cells infected with the ΔtonB123 mutant for 6 h (P < 0.001). The invasiveness was quantified by measuring the number of bacterial cells that translocated from the upper to the lower chamber of the Transwell. Consistent with the in vivo data described above, approximately 3.8 × 105 CFU/ml of wild-type cells were detected in the lower chamber after 3 h of incubation, and the cell counts reached 5.0 × 108 CFU/ml after 6 h, whereas the translocation of the ΔtonB123 mutant was not detected up to 5 h after infection (Fig. 4B) (P < 0.001). In parallel with the translocation of V. vulnificus, the LDH release in the lower chamber gradually increased and reached 100% by 6 h following wild-type infection, whereas negligible LDH release was detected from the ΔtonB123 mutant-infected cells (Fig. 4C) (P < 0.001). The cytotoxicity to HCA-7 cells in the upper chamber was also delayed in the ΔtonB123 strain, as observed with the HeLa cell infection model (Fig. 4D) (P < 0.001). The in vitro data, coupled with the in vivo invasion results, demonstrate the importance of three TonB systems for traversing the intestinal epithelial barrier by virulent V. vulnificus CMCP6.

FIG 4.

Attenuated translocation across a polarized HCA-7 monolayer in the tonB123 triple mutant. HCA-7 cells grown on Transwell filters were apically exposed to log-phase V. vulnificus cells. The invasiveness was determined by measuring the change in TER (A) and the number of bacterial cells that translocated from the upper chamber to the lower chamber of the Transwell (B). Viable bacterial cells were counted by plating on 2.5% NaCl HI agar plates. The LDH release in the lower chamber (basolateral) (C) and the upper chamber (apical) (D) was also determined. The values are means and standard errors from three independent experiments that were performed in five replicates. Statistical analyses of the tonB123 mutant using a two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc tests revealed an attenuated translocation across the polarized HCA-7 monolayer in the ΔtonB123 mutant compared to the wild-type strain (***, P < 0.001).

All three TonB systems contribute to the motility and adhesion of V. vulnificus CMCP6.

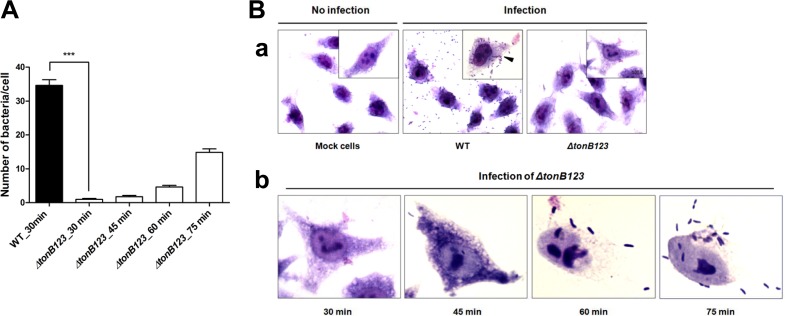

Based on the above results, we speculated that the defects of the ΔtonB123 mutant somehow affected bacterial attachment to host cells, leading to defects in transepithelial invasion into the bloodstream or in translocation to the lower Transwell chamber. First, we performed the adhesion assay in which HeLa cells were infected with V. vulnificus strains at an MOI of 250, and the bacterial cells that adhered to host cells were counted. The number of the ΔtonB123 cells that adhered to a single HeLa cell was approximately 34-fold lower than that of the wild-type strain after 30 min of infection (Fig. 5A) (P < 0.001). The wild-type strain formed small clusters of aggregated bacteria on the HeLa cell surface, consequently causing cell lysis. In contrast, few ΔtonB123 cells attached to the HeLa cell surface, and the infected host cells maintained cell contours almost like those of uninfected cells (Fig. 5B, panel a). The adherence of the ΔtonB123 mutant to host cells was further observed at later time points. The number of ΔtonB123 cells adhering to HeLa cells gradually increased in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 5A and B, panel b), providing an explanation of why cytotoxicity was delayed in the ΔtonB123 strain (Fig. 2A).

FIG 5.

Significantly decreased adhesion to host cells in the tonB123 triple mutant. (A) HeLa cells were treated with log-phase V. vulnificus cells at an MOI of 250 for 30, 45, 60, and 75 min, and the bacterial cells that adhered to the HeLa cells were counted. Data are means plus SEM from three independent experiments that were performed in 10 replicates. Statistical analysis was carried out using Student's t test (***, P < 0.001 compared to the wild-type strain). (B) Morphology of infected HeLa cells after Giemsa staining. (a) V. vulnificus-infected cells were observed after 30 min of infection (at magnifications of ×400 and ×1,000 [inset]). (b) The number of ΔtonB123 cells adhering to HeLa cells gradually increased in a time-dependent manner (magnification, ×1,000). The adherent V. vulnificus cells (filled arrowhead) are indicated.

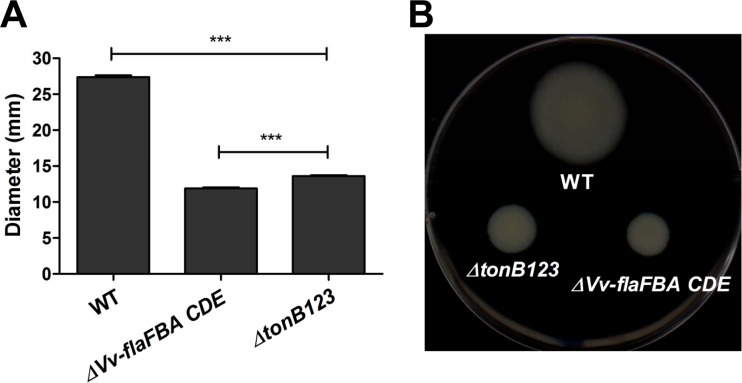

Given that motility is essential for the adhesion of enteropathogens to host cells (45), we further explored whether the ΔtonB123 mutant also has a motility defect by measuring the migration of V. vulnificus on semisolid agar surfaces. The tonB12 and tonB123 mutants exhibited significant defects in motility compared with the wild-type strain (Fig. 6; also, see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material) (P < 0.001). Remarkably, the ΔtonB123 mutant manifested a profound defect in motility relative to the ΔtonB12 strain, showing an approximately 60% decrease in the migration area compared to a 10% decrease shown by the ΔtonB12 strain (Fig. 6) (P < 0.001). The reduced motility in the ΔtonB12 strain was fully restored by in trans complementation with any one of the three TonB systems (see Fig. S5B in the supplemental material), while the defect in the ΔtonB123 mutant was not restore by any means (see Fig. S5C in the supplemental material). Taking these results together, we supposed that the defects of the ΔtonB123 mutant in cytotoxicity and invasiveness could be attributed to the motility defect, which consequently resulted in decreased adhesion to host cells. The motility assay results once again indicated the dominant functions of TonB1 and TonB2 reported previously by other groups (20, 21); the ΔtonB12 mutant showed a significant motility defect, while all other single or double operon mutants did not show any change in motility. Next we tried to determine why motility was defective in the ΔtonB123 mutant.

FIG 6.

Decreased motility in the tonB123 triple mutant. (A) Log-phase cells were inoculated onto motility agar plates containing 0.3% agar and incubated for 12 h at 37°C. The diameters of motility areas are the means plus SEM from three independent experiments that were performed in fifteen replicates. Statistical analysis was carried out using Student's t test (***, P < 0.001 compared to the wild-type strain). (B) The areas of motility of V. vulnificus were photographed.

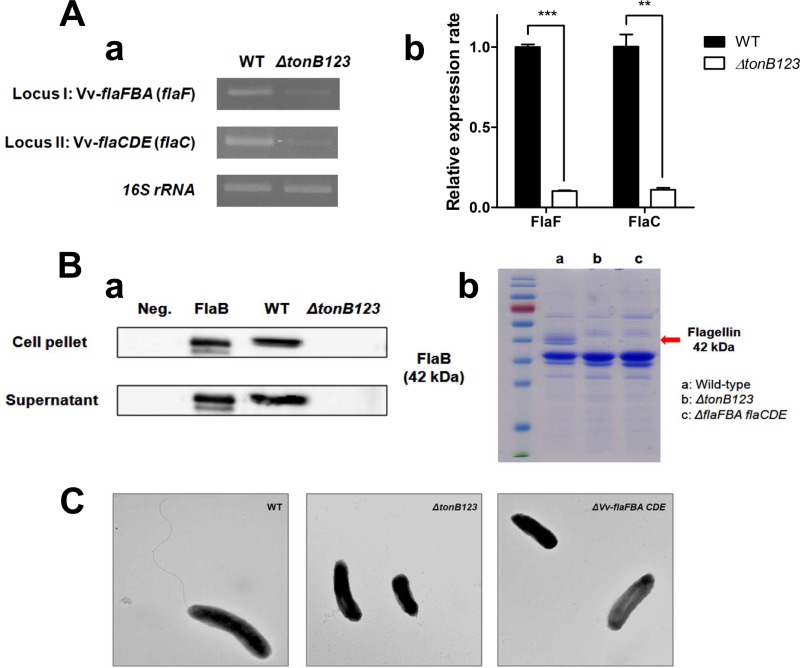

A complete functional deficiency of tonB123 resulted in a significant decrease in the flagellin expression of V. vulnificus CMCP6.

Previously, Alice et al. reported that the genes coding for flagellar proteins are induced under iron-rich conditions (20). It has been reported that flagellar biogenesis is a requisite for host cell adhesion and cytotoxicity (32, 45, 46). Hence, we speculated that the three TonB systems would play important roles in the flagellar biogenesis by supplying sufficient level of iron. In addition, we found the Fur-binding site (CAAATGATAATAATTTGCAAT) in the promoter regions of flagellin genes (see Table S3 in the supplemental material), strongly suggesting the relationship between TonB system-mediated iron assimilation and flagellation. We examined the transcription and translation of the flagellin genes in the wild-type and the ΔtonB123 backgrounds. The transcripts of flagellin genes were determined by conventional and real-time RT-PCR (Fig. 7A). Since V. vulnificus CMCP6 has a total of six flagellin genes (flaA, flaB, flaC, flaD, flaE, and flaF) organized into two loci (flaFBA and flaCDE) in chromosome I (32), we designed two primer sets to amplify flaF and flaC for each flagellin cluster specifically. The amount of flaF and flaC amplicons in the ΔtonB123 mutant was significantly lower than that in the wild-type strain (Fig. 7A) (P < 0.001 for flaF and P < 0.01 for flaC). Complementation with any TonB system could not restore flagellin gene expression in the ΔtonB123 mutant (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material) (P > 0.05). This result explained why complementation did not work for the motility of the ΔtonB123 mutant, even with the dominant TonB2 operon (see Fig. S5C in the supplemental material).

FIG 7.

Defects of the transcription (A) and translation (B) of flagellin genes and loss of flagellation in the tonB123 triple mutant (C). (A) RNA was isolated from log-phase bacterial cells that had been cultured in the rat peritoneal cavity and was then converted to cDNA. Conventional (a) and real-time (b) RT-PCR was performed using primers specific for flaF and flaC, as shown in Table S2 in the supplemental material. The error bars represent the standard errors of means from three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was carried out using Student's t test (**, P < 0.01, and ***, P < 0.001, compared to the wild-type strain). (B) (a) Bacteria were cultured in 2.5% NaCl HI to log-phase growth, and then Western blot analysis was subsequently carried out in the V. vulnificus cell pellet and culture supernatant using an anti-FlaB antibody (a band of approximately 42 kDa). The ΔflaFBA flaCDE strain was used as a negative control (Neg.). (b) The OMP preparations were analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE. Two major OMP bands were missing in the ΔtonB123 mutant compared to the wild-type strain, which were subsequently identified as flagellin proteins (42 kDa) using MALDI-TOF MS. (C) Electron micrograph of the log-phase V. vulnificus strains under ×25,000 magnification.

To confirm the flagellin expression defect at the protein level, Western blot analysis was subsequently carried out in the V. vulnificus cell pellet and supernatant to detect FlaB, which has been well characterized as the representative and major flagellin structural protein among proteins with six flagellins (hexa flagellin proteins) (32). We observed a tight correlation between the quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) and Western blotting results. FlaB protein was detected in wild-type strain but not in the ΔtonB123 mutant in both cell pellets and culture supernatants (Fig. 7B, panel a). Interestingly, the data were strongly supported by the changes in OMP profile of the tonB123 mutant compared to the wild-type strain. Two major OMP bands were missing in the ΔtonB123 strain which were subsequently identified as flagellin proteins (42 kDa) using MALDI-TOF MS (Fig. 7B, panel b). Additionally, electron microscopy showed that the ΔtonB123 strain totally lacked flagellation, like the flaFBA flaCDE hexa mutant constructed in our previous study (32) (Fig. 7C). Taken together, the three TonB systems appear to play an essential role in the flagellation of V. vulnificus CMCP6 by supplying sufficient iron for the expression of flagellin genes.

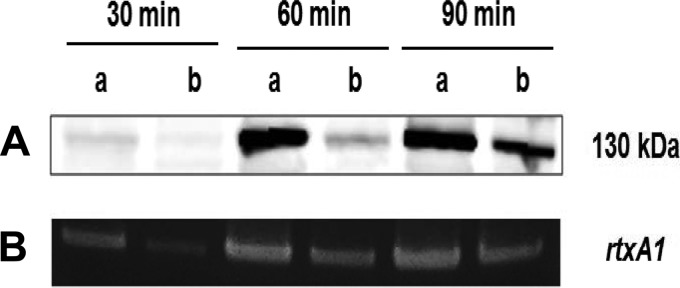

The tonB123 triple mutant was defective in the production of RtxA1 cytotoxin.

RtxA1 is a crucial cytotoxin that is involved in cellular damage and the necrosis of infected tissues, allowing bacterial penetration into the bloodstream through the intestinal epithelium (31, 47–50). Previously, we reported that V. vulnificus CMCP6 induces RtxA1 toxin production to kill host cells after coming into close contact with host cells (31). We hypothesized that impaired attachment to host cells hampered production and consequently host cell killing and tissue invasion. We performed a Western blot analysis of cell pellets to assess toxin production at 30, 60, and 90 min after HeLa cell infection. RtxA1 was detected using an anti-GD domain antibody targeting the C-terminal fragment (RtxA1-C; approximately 130 kDa), which is internalized in the host cell cytoplasm (36). Significantly less RtxA1 protein was detected in the infection caused by the ΔtonB123 mutant than in that caused by the wild-type strain (Fig. 8A). We also examined rtxA1 transcription by RT-PCR using mRNA from bacterial cells that adhered to HeLa cells at various time points. Like the Western blot analysis, in the HeLa cell coculture model, the ΔtonB123 mutant showed significantly less transcription of rtxA1 at all time points tested than the wild-type strain (Fig. 8B), while a comparable transcription rate was observed in both strains in 2.5% NaCl HI broth (see Fig. S7 in the supplemental material). Thus, because of the difficulty of coming into contact with host cells (Fig. 5), the triple tonB123 mutant manifested defective RtxA1 toxin production. The RtxA1 production in the ΔtonB123 mutant was gradually delayed in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 8), which correlated with host cell adhesion (Fig. 5) and cytotoxicity (Fig. 2A). The TonB systems seem to have no direct regulatory role with regard to the RtxA1 operon through Fur, since no conserved Fur-binding sites were found in the promoter region and the toxin production reached the wild-type level after a delayed attachment to host cells.

FIG 8.

Significantly lower translation (A) and transcription (B) of rtxA1 in the tonB123 triple mutant infecting HeLa cells. (A) Log-phase V. vulnificus cells were incubated with HeLa cells on a 6-well plate at an MOI of 100 for 30, 60, and 90 min. The cells in each well were lysed by lysis buffer and concentrated with an Amicon Ultra-0.5 centrifugal filter. The RtxA1 proteins were detected by Western blotting using an anti-GD domain antibody (RtxA1-C, a band of approximately 130 kDa). (B) RNA was isolated from bacterial cells using a HeLa cell coculture model as described above. cDNA synthesis and RT-PCR were performed using primers specific for the rtxA1 gene as shown in Table S2 in the supplemental material. Lanes: a, wild type; b, ΔtonB123 mutant.

DISCUSSION

During the host-pathogen interaction, V. vulnificus is confronted with a host defense called “nutritional immunity” that sequesters essential nutrient metals, such as iron, which is required for heme biogenesis (51–55). Bacterial pathogens have developed a large variety of systems to take up those nutrients from animal hosts (4, 51). In Gram-negative bacteria, the TonB system plays crucial roles in the transport of iron-siderophore complexes (15, 16), vitamin B12 (14), and a wide range of substrates, including zinc, nickel, maltodextrins, and sucrose (17–19, 56). There are three TonB systems in V. vulnificus CMCP6 (20): TonB1 and TonB2 were reported to play predominant roles in the iron transport of siderophores and in the pathogenesis of V. vulnificus (20, 21), while there is scanty functional information about TonB3. The maintenance of a third TonB system in V. vulnificus CMCP6 genomes, which is similar to the TonB2 system in its gene arrangement and orientation (20–22), raised the following questions. Why has V. vulnificus CMCP6 maintained three TonB systems throughout evolution? How does each TonB system contribute to the virulence of V. vulnificus, and are all three TonB systems necessary for the virulence? Through in vitro and in vivo experiments, in the present study we have addressed these questions, at least in part, and found that these systems are coordinated to contribute to V. vulnificus CMCP6 virulence. We demonstrated the contribution of three TonB systems to flagellation, motility, adhesion, cytotoxicity, invasion, and in vivo virulence. The three TonB systems appear to complement each other's functions, and only the complete abrogation of all three TonB operons caused severe defects in virulence phenotypes. This is the first report to document the association between TonB systems and flagellation in V. vulnificus CMCP6. Since proper flagellation is very important for flagellum-mediated locomotion in the marine environment and motility and adhesion to the host cells during infection (32, 45, 57), the pathogens that lost flagellation became impaired for contacting to host cells, leading to a decrease in RtxA1 production. As a result, a series of virulence defects were detected in the tonB123 triple mutant, including delayed cytotoxicity, impaired invasiveness, and decreased lethality for mice.

In a previous study (20), Crosa's group showed that a mutant having in-frame deletions in both tonB1 and tonB2 genes (not all structural genes in TonB12 loci) manifested a 4-log scale increase of subcutaneous LD50 in iron-overloaded mice compared with the isogenic wild-type strain. Strangely, intraperitoneal infection did not show any LD50 difference between the mutant and wild-type strains in either iron-overloaded or normal-iron-level mice. The finding that only subcutaneous infection, not intraperitoneal infection, showed a significant virulence decrease in the mutant with defects in the TonB1 and TonB2 systems corroborates our suggestion: the TonB systems play important roles in the invasion process. However, their results are contradictory to ours in that we saw LD50 changes only in normal-iron-level mice, not in iron-overloaded mice. Given that TonB1 and TonB2 systems are induced by iron deprivation and play important roles in iron assimilation (20), it is curious that they observed virulence impairment only in iron-overloaded animals. As for experimental models, the only difference between our study and theirs is that we used deletions of the entire structural genes in TonB loci for functional inactivation, while they used in-frame deletions of the most important structural tonB genes in the operons. We cautiously speculate that our approach, using a complete functional deficiency of TonB systems and complementation with cosmid clones harboring whole operons, represents a broader range of physiological interaction landscapes among the three TonB systems in V. vulnificus CMCP6.

Taken together, the results reported here indicate that all three TonB systems of V. vulnificus CMCP6 coordinately complement each other for iron assimilation and full virulence expression by ensuring flagellar biogenesis. The major function of TonB systems might not be to supply iron for the in vivo growth of V. vulnificus CMCP6, since the tonB123 triple mutant grew very well, like the isogenic wild-type strain, in the ileum (Fig. 3), in DMEM without iron supplementation (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), in the peritoneal cavity of normal rats (see Fig. S4B [panel a] in the supplemental material), and even in blood (see Fig. S4B [panel b] in the supplemental material). Rather, the raison d'être of three TonB systems in V. vulnificus CMCP6 should involve in supplying a sufficient level of iron, allowing the expression of flagellar biogenesis genes, which are located higher in the hierarchy of the virulence expression cascade. This hypothesis is corroborated by the report by Crosa's group showing that flagellar motility genes are induced under conditions of sufficient iron (20). Our new findings bring more critical insight into the pathogenic significance of these TonB systems in V. vulnificus CMCP6 and further suggest that new antibacterial agents that block the dual functions of TonB would suppress robust iron acquisition and virulence expression.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the KHIDI, funded by the MHW, Republic of Korea (HI14C0187), and an NRF grant from the MSIP (NRF-2013R1A2A2A01005011), Republic of Korea.

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00821-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brennt CE, Wright AC, Dutta SK, Morris JG. 1991. Growth of Vibrio vulnificus in serum from alcoholics: association with high transferrin iron saturation. J Infect Dis 164:1030–1032. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.5.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ganz T, Nemeth E. 2011. Hepcidin and disorders of iron metabolism. Annu Rev Med 62:347–360. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-050109-142444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones MK, Oliver JD. 2009. Vibrio vulnificus: disease and pathogenesis. Infect Immun 77:1723–1733. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01046-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linkous DA, Oliver JD. 1999. Pathogenesis of Vibrio vulnificus. FEMS Microbiol Lett 174:207–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oliver JD. 2005. Wound infections caused by Vibrio vulnificus and other marine bacteria. Epidemiol Infect 133:383–391. doi: 10.1017/S0950268805003894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strom MS, Paranjpye RN. 2000. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of Vibrio vulnificus. Microbes Infect 2:177–188. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(00)00270-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gulig PA BK, Starks AM. 2005. Molecular pathogenesis of Vibrio vulnificus. J Microbiol 43:118–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun V. 1995. Energy-coupled transport and signal transduction through the Gram-negative outer membrane via TonB-ExbB-ExbD-dependent receptor proteins. FEMS Microbiol Rev 16:295–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1995.tb00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faraldo-Gomez JD, Sansom MSP. 2003. Acquisition of siderophores in Gram-negative bacteria. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4:105–116. doi: 10.1038/nrm1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim CM, Chung YY, Shin SH. 2009. Iron differentially regulates gene expression and extracellular secretion of Vibrio vulnificus cytolysin-hemolysin. J Infect Dis 200:582–589. doi: 10.1086/600869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim CM, Kim SC, Shin SH. 2012. Iron-mediated regulation of metalloprotease VvpE production in Vibrio vulnificus. New Microbiol 35:481–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright AC, Simpson LM, Oliver JD. 1981. Role of iron in the pathogenesis of Vibrio vulnificus infections. Infect Immun 34:503–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larsen RA, Letain TE, Postle K. 2003. In vivo evidence of TonB shuttling between the cytoplasmic and outer membrane in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 49:211–218. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shultis DD, Purdy MD, Banchs CN, Wiener MC. 2006. Outer membrane active transport: structure of the BtuB:TonB complex. Science 312:1396–1399. doi: 10.1126/science.1127694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miethke M, Marahiel MA. 2007. Siderophore-based iron acquisition and pathogen control. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 71:413–451. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00012-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wandersman C, Delepelaire P. 2004. Bacterial iron sources: from siderophores to hemophores. Annu Rev Microbiol 58:611–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blanvillain S, Meyer D, Boulanger A, Lautier M, Guynet C, Denancé N, Vasse J, Lauber E, Arlat M. 2007. Plant carbohydrate scavenging through tonB-dependent receptors: a feature shared by phytopathogenic and aquatic bacteria. PLoS One 2:e224. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neugebauer H, Herrmann C, Kammer W, Schwarz G, Nordheim A, Braun V. 2005. ExbBD-dependent transport of maltodextrins through the novel MalA protein across the outer membrane of Caulobacter crescentus. J Bacteriol 187:8300–8311. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.24.8300-8311.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schauer K, Gouget B, Carrière M, Labigne A, De Reuse H. 2007. Novel nickel transport mechanism across the bacterial outer membrane energized by the TonB/ExbB/ExbD machinery. Mol Microbiol 63:1054–1068. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alice AF, Naka H, Crosa JH. 2008. Global gene expression as a function of the iron status of the bacterial cell: influence of differentially expressed genes in the virulence of the human pathogen Vibrio vulnificus. Infect Immun 76:4019–4037. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00208-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kustusch RJ, Kuehl CJ, Crosa JH. 2012. The ttpC gene is contained in two of three TonB systems in the human pathogen Vibrio vulnificus, but only one is active in iron transport and virulence. J Bacteriol 194:3250–3259. doi: 10.1128/JB.00155-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alice AF, Crosa JH. 2012. The TonB3 system in the human pathogen Vibrio vulnificus is under the control of the global regulators Lrp and cyclic AMP receptor protein. J Bacteriol 194:1897–1911. doi: 10.1128/JB.06614-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim HU, Kim SY, Jeong H, Kim TY, Kim JJ, Choy HE, Yi KY, Rhee JH, Lee SY. 2011. Integrative genome-scale metabolic analysis of Vibrio vulnificus for drug targeting and discovery. Mol Syst Biol 7:460–460. doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morrison SS, Williams T, Cain A, Froelich B, Taylor C, Baker-Austin C, Verner-Jeffreys D, Hartnell R, Oliver JD, Gibas CJ. 2012. Pyrosequencing-based comparative genome analysis of Vibrio vulnificus environmental isolates. PLoS One 7:e37553. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan W, Verma V, Jeong K, Kim SY, Jung CH, Lee SE, Rhee JH. 2014. Molecular characterization of vulnibactin biosynthesis in Vibrio vulnificus indicates the existence of an alternative siderophore. Front Microbiol 5:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller VL, Mekalanos JJ. 1988. A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J Bacteriol 170:2575–2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horton RM, Hunt HD, Ho SN, Pullen JK, Pease LR. 1989. Engineering hybrid genes without the use of restriction enzymes: gene splicing by overlap extension. Gene 77:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90359-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim YR, Lee SE, Kim CM, Kim SY, Shin EK, Shin DH, Chung SS, Choy HE, Progulske-Fox A, Hillman JD, Handfield M, Rhee JH. 2003. Characterization and pathogenic significance of Vibrio vulnificus antigens preferentially expressed in septicemic patients. Infect Immun 71:5461–5471. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.10.5461-5471.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim SY, Lee SE, Kim YR, Kim CM, Ryu PY, Choy HE, Chung SS, Rhee JH. 2003. Regulation of Vibrio vulnificus virulence by the LuxS quorum-sensing system. Mol Microbiol 48:1647–1664. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee SE, Kim SY, Kim CM, Kim MK, Kim YR, Jeong K, Ryu HJ, Lee YS, Chung SS, Choy HE, Rhee JH. 2007. The pyrH gene of Vibrio vulnificus is an essential in vivo survival factor. Infect Immun 75:2795–2801. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01499-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim YR, Lee SE, Kook H, Yeom JA, Na HS, Kim SY, Chung SS, Choy HE, Rhee JH. 2008. Vibrio vulnificus RTX toxin kills host cells only after contact of the bacteria with host cells. Cell Microbiol 10:848–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim SY, Thanh XTT, Jeong K, Kim SB, Pan SO, Jung CH, Hong SH, Lee SE, Rhee JH. 2014. Contribution of six flagellin genes to the flagellum biogenesis of Vibrio vulnificus and in vivo invasion. Infect Immun 82:29–42. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00654-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee J, Mo JH, Katakura K, Alkalay I, Rucker AN, Liu YT, Lee HK, Shen C, Cojocaru G, Shenouda S, Kagnoff M, Eckmann L, Ben-Neriah Y, Raz E. 2006. Maintenance of colonic homeostasis by distinctive apical TLR9 signalling in intestinal epithelial cells. Nat Cell Biol 8:1327–1336. doi: 10.1038/ncb1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lo Scrudato M, Blokesch M. 2012. The regulatory network of natural competence and transformation of Vibrio cholerae. PLoS Genet 8:e1002778. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim YR, Lee SE, Kang IC, Nam KI, Choy HE, Rhee JH. 2013. A bacterial RTX toxin causes programmed necrotic cell death through calcium-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction. J Infect Dis 207:1406–1415. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee SE, Shin SH, Kim SY, Kim YR, Shin DH, Chung SS, Lee ZH, Lee JY, Jeong KC, Choi SH, Rhee JH. 2000. Vibrio vulnificus has the transmembrane transcription activator ToxRS stimulating the expression of the hemolysin gene vvhA. J Bacteriol 182:3405–3415. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.12.3405-3415.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ptashne M. 1992. A genetic switch: phage λ and higher organisms, 2nd ed Cell Press & Blackwell Scientific Publications, Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsolis RM, Bäumler AJ, Stojiljkovic I, Heffron F. 1995. Fur regulon of Salmonella typhimurium: identification of new iron-regulated genes. J Bacteriol 177:4628–4637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldberg MB, Boyko SA, Calderwood SB. 1990. Transcriptional regulation by iron of a Vibrio cholerae virulence gene and homology of the gene to the Escherichia coli Fur system. J Bacteriol 172:6863–6870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gao H, Zhou D, Li Y, Guo Z, Han Y, Song Y, Zhai J, Du Z, Wang X, Lu J, Yang R. 2008. The iron-responsive Fur regulon in Yersinia pestis. J Bacteriol 190:3063–3075. doi: 10.1128/JB.01910-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. 1997. The CLUSTAL_X Windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res 25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heithoff DM, Conner CP, Mahan MJ. 1997. Dissecting the biology of a pathogen during infection. Trends Microbiol 5:509–513. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee SH, Hava DL, Waldor MK, Camilli A. 1999. Regulation and temporal expression patterns of Vibrio cholerae virulence genes during Infection. Cell 99:625–634. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81551-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee JH, Rho JB, Park KJ, Kim CB, Han YS, Choi SH, Lee KH, Park SJ. 2004. Role of flagellum and motility in pathogenesis of Vibrio vulnificus. Infect Immun 72:4905–4910. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.8.4905-4910.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Terashima H, Kojima S, Homma M. 2008. Flagellar motility in bacteria: structure and function of flagellar motor. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 270:39–85. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(08)01402-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hor LI, Chen CL. 2013. Cytotoxins of Vibrio vulnificus: functions and roles in pathogenesis. BioMedicine 3:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.biomed.2012.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jeong HG, Satchell KJ. 2012. Additive function of Vibrio vulnificus MARTX(Vv) and VvhA cytolysins promotes rapid growth and epithelial tissue necrosis during intestinal infection. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002581. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lo HR, Lin JH, Chen YH, Chen CL, Shao CP, Lai YC, Hor LI. 2011. RTX toxin enhances the survival of Vibrio vulnificus during infection by protecting the organism from phagocytosis. J Infect Dis 203:1866–1874. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wright AC, Morris JG. 1991. The extracellular cytolysin of Vibrio vulnificus: inactivation and relationship to virulence in mice. Infect Immun 59:192–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schaible UE, Kaufmann SHE. 2004. Iron and microbial infection. Nat Rev Microbiol 2:946–953. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weinberg ED. 2009. Iron availability and infection. Biochim Biophys Acta 1790:600–605. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murciano C, Hor LI, Amaro C. 2015. Host-pathogen interactions in Vibrio vulnificus: responses of monocytes and vascular endothelial cells to live bacteria. Future Microbiol 10:471–487. doi: 10.2217/fmb.14.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Skaar EP. 2010. The battle for iron between bacterial pathogens and their vertebrate hosts. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000949. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arezes J, Jung G, Gabayan V, Valore E, Ruchala P, Gulig PA, Ganz T, Nemeth E, Bulut Y. 2015. Hepcidin-induced hypoferremia is a critical host defense mechanism against the siderophilic bacterium Vibrio vulnificus. Cell Host Microbe 17:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rodionov DA, Hebbeln P, Gelfand MS, Eitinger T. 2006. Comparative and functional genomic analysis of prokaryotic nickel and cobalt uptake transporters: evidence for a novel group of ATP-binding cassette transporters. J Bacteriol 188:317–327. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.1.317-327.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ottemann KM, Miller JF. 1997. Roles for motility in bacterial-host interactions. Mol Microbiol 24:1109–1117. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4281787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Milton DL, O'Toole R, Horstedt P, Wolf-Watz H. 1996. Flagellin A is essential for the virulence of Vibrio anguillarum. J Bacteriol 178:1310–1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Staskawicz B, Dahlbeck D, Keen N, Napoli C. 1987. Molecular characterization of cloned avirulence genes from race 0 and race 1 of Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea. J Bacteriol 169:5789–5794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ditta G, Stanfield S, Corbin D, Helinski DR. 1980. Broad host range DNA cloning system for gram-negative bacteria: construction of a gene bank of Rhizobium meliloti. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 77:7347–7351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.