Abstract

The aim of this meta-analysis is to compare the perioperative morbidity and mortality outcomes of robotic-assisted thoracic surgery (RATS) with open thoracic surgery (OTS) for patients with lung cancer. We searched articles indexed in the Pubmed and Sciencedirect published as of July 2015 that met our predefined criteria. A meta-analysis was performed by combining the results of reported incidences of perioperative morbidity and mortality. The relative risk (RR) was used as a summary statistic. Five eligible articles with 2433 subjects were considered in the analysis (5 articles for morbidity, while 3 articles for mortality). Overall, pooled analysis indicated that perioperative morbidity and mortality rate was significantly lower among patients who underwent RATS than patients who underwent OTS (for morbidity: RR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.75 to 0.92; P<0.01; for mortality: RR, 0.14; 95% CI, 0.03 to 0.59; P=0.007). No evidence of publication bias was observed. In conclusion, this meta-analysis showed that RATS resulted in significantly lower perioperative morbidity and mortality rate compared with OTS cases. Thus, we suggest RATS be an appropriate alternative to OTS for lung cancer resection. RATS should be studied further in selected centers and compared with OTS in a randomized fashion to better define its potential advantages and disadvantages.

Keywords: Robot-assisted thoracic surgery, robotic-assisted thoracic surgery, lung cancer, meta-analysis

Introduction

The revolution of minimally invasive surgery that began in the 1980s has made a significant impact in many specialties of surgery. There are two different minimally invasive approaches, robotic-assisted thoracic surgery (RATS) and video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS), which are performed for lung cancer resection [1]. In early 1990s, VATS came into being and rapidly progressed to complex procedures of mediastinal tumors with the incorporation of video technology [2]. Compared with open thoracic surgery (OTS), the purported benefits of VATS in lung cancer surgery include smaller incisions, less complications, less respiratory compromise, and faster recovery time [3,4]. In multivariate analysis, VATS was associated independently with a reduced risk of complications [5,6]. However, the general thoracic surgical community has been relatively slow in adapting VATS more widely, because of its 2D vision with lack of depth perception and the use of long rigid instruments in a counter intuitive manner [7].

RATS, which has been proposed as an alternative to VATS, has emerged as a viable minimally invasive surgery for lung cancer resection [8,9]. The introduction of Da Vinci surgical system and the endo-wrist technology leading to intuitive instrument movements has helped overcome the limitations of VATS and allowed the surgeon to virtually perform the lobectomy with his hands without the morbidity of a thoracotomy [10]. It provides excellent 3D vision with magnification (a view even better than open surgery) and precise dissection with much improved surgeon ergonomics [11]. Some clinical studies have demonstrated that RATS is safe with superior clinical outcomes when compared with similar patients undergoing OTS [8,12]. However, some studies find that RATS results in similar outcomes compared with OTS cases [13-15].

Meta-analysis is a well-established statistical tool that serves for integration of data from independent studies in order to formulate more general conclusions. We therefore undertook a meta-analysis of studies to compare the morbidity and mortality of RATS with OTS for lung cancer resection.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

We performed a systematic search of Pubmed and Sciencedirect up to July 2015 using the searching strategy: (robot-assisted OR robot OR robotic approaches) AND (lung cancer or lung carcinoma). We screened the reference lists of all eligible studies to identify potentially eligible studies, and sent emails to the authors of identified studies for additional information if necessary.

Selection criteria

Two authors conducted the search independently. Titles and abstracts were screened for subject relevance. Studies that could not be definitely excluded based on abstract information were also selected for full text screening. Eligible studies had to meet the following criteria: (1) human study; (2) retrospective observational study, case-control study, cohort study or randomized clinical trial; (3) Eligible studies for the present systematic review included those in which patients with histologically proven lung cancer; (4) studies providing data of perioperative morbidity or mortality for both RATS and OTS for lung cancer. The exclusion criteria included: (1) in vitro or laboratory study; (2) animal study, review or case report; (3) studies providing neither morbidity nor mortality for either RATS or OTS; (4) sample less than 20.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two authors independently extracted data using a standard form. The following information was extracted from each included study: country, first author’s family name, year of publication, study type, study period, demography of subjects (number of subjects and age), data of morbidity and mortality. Two investigators independently reviewed each retrieved article. Discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved by discussion and consensus.

Two authors assessed the quality independently. The qualities of all included studies were assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). Using the tool, each study is judged on eight items, categorized into three groups: the selection of the study groups; the comparability of the groups; and the ascertainment of either the exposure or outcome of interest for case-control or cohort studies respectively. Stars awarded for each quality item serve as a quick visual assessment. Stars are awarded such that the highest quality studies are awarded up to nine stars. Studies were graded as good quality if they awarded 6 to 9 stars; fair if they awarded 3 to 5 stars; and poor if they awarded less than 3 stars.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis was performed by combining the results of reported incidences of perioperative morbidity and mortality. The relative risk (RR) was used as a summary statistic. The RRs were calculated using either fixed-effects models or, in the presence of heterogeneity, random-effects models. Heterogeneity between studies was tested through the Chi-square and I-square tests. If the I2 value was greater than 50% and the p value was less than 0.05, the meta-analysis was considered as homogeneous. In the presence of heterogeneity, subgroup analyses were used to identify the possible sources of heterogeneity. Publication bias was measured using Begg’s tests and visualization of funnel plots. All p-values were two sided. All statistical analyses were performed with Stata version 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Literature search

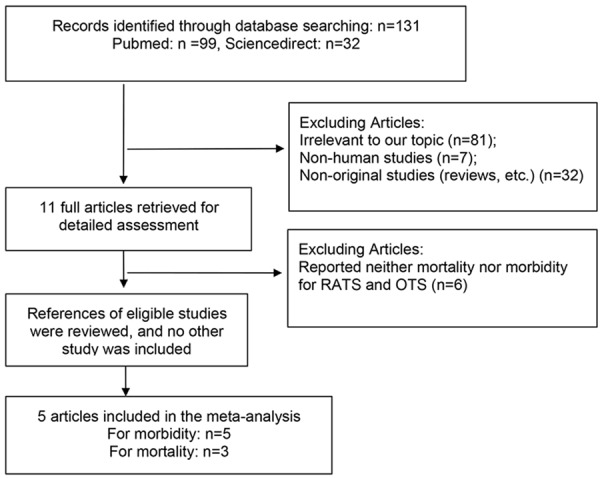

The literature search yielded a total of 131 primary studies. These studies were included for full-text assessment, of which 126 were excluded for one of the following reasons: (1) irrelevant to our topic (n=81), (2) non-human studies (n=32), (3) non-original studies (reviews, etc.) (n=7), (4) articles reported neither mortality nor morbidity for RATS and OTS (n=6). Overall, 5 eligible articles with 2433 subjects from 5 retrospective observational studies were considered in the analysis, in which 5 articles for morbidity, while 3 articles for mortality [8,12-15]. A flow diagram of the study selection process is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of screened and included articles.

Study characteristics and quality assessment

All studies included in the present meta-analysis were from retrospective observational studies. The overall study quality averaged 6 stars (range, 5-7) on a scale of 0 to 9. In these 5 retrospective observational studies, 2433 patients with lung cancer were compared, including 671 patients who underwent VATS and 1762 patients who underwent OTS. The number of subjects in each study ranged from 108 to 1644. The mean age of population ranged from 66 to 70 years. The earliest study was published in 2010, and the latest in 2014. By geographic location, studies were conducted in 3 different countries (USA, U.K. and Italy). The detailed characteristics of the included studies and the results of the quality assessment were summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of relevant studies identified in the present meta-analysis on RATS versus OTS for lung cancer

| Studies | Country | Study type | Study period | RATS | OTS | Quality score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Mean age | No. | Morbidity | Mortality | Mean age | No. | Morbidity | Mortality | |||||

| Veronesi 2010 | Italy | ROS | 2006-2008 | NR | 54 | 11 | NR | NR | 54 | 10 | NR | 5 |

| Cerfolio 2011 | U.K. | ROS | 2010-2011 | 66 | 106 | 28 | 0 | 66 | 318 | 120 | 11 | 6 |

| Daniel 2013 | USA | ROS | 1998-2012 | 67 | 43 | 22 | 0 | 70 | 88 | 58 | 3 | 6 |

| Deen 2014 | USA | ROS | 2008-2012 | 68 | 57 | 32 | NR | 68 | 69 | 30 | NR | 6 |

| Kent 2014 | USA | ROS | 2008-2010 | 67 | 411 | 180 | 1 | 66 | 1233 | 667 | 25 | 7 |

RATS, robotic-assisted thoracic surgery; OTS, open thoracic surgery; ROS, retrospective observational study; NR, not reported.

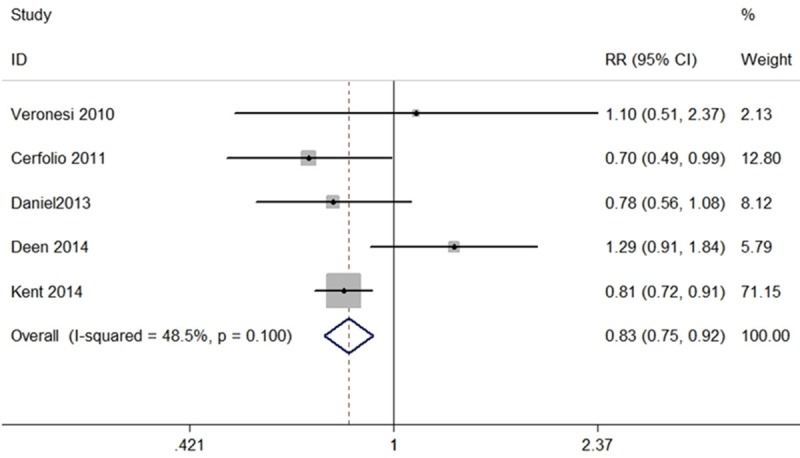

Assessment of perioperative morbidity

The fixed-effects meta-analysis results indicated that the overall perioperative morbidity rate was significantly lower among patients who underwent RATS than patients who underwent OTS (RR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.75 to 0.92; P<0.01) (Figure 2). The 5 sets of results showed no significant amount of heterogeneity (I2=48.5%, P=0.10) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the RR of perioperative morbidity after RATS vs. OTS for lung cancer.

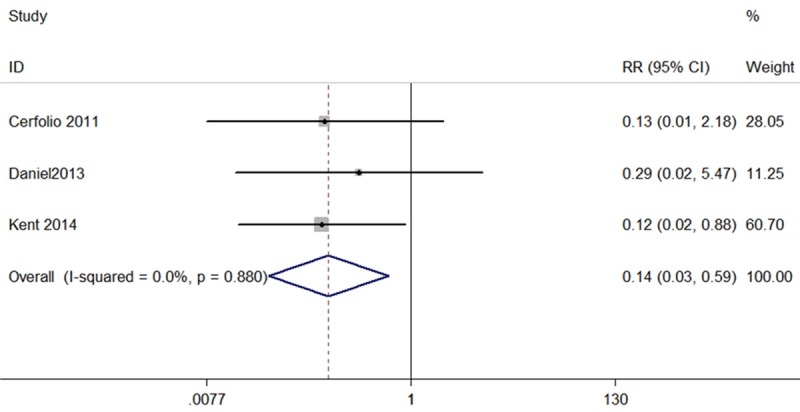

Assessment of perioperative mortality

The present meta-analysis in fixed-effects model showed that patients who underwent RATS had lower perioperative mortality rate than patients who underwent OTS (RR, 0.14; 95% CI, 0.03 to 0.59; P=0.007) (Figure 3). The 3 sets of results showed no significant amount of heterogeneity (I2=0, P=0.88) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the RR of perioperative mortality after RATS vs. OTS for lung cancer.

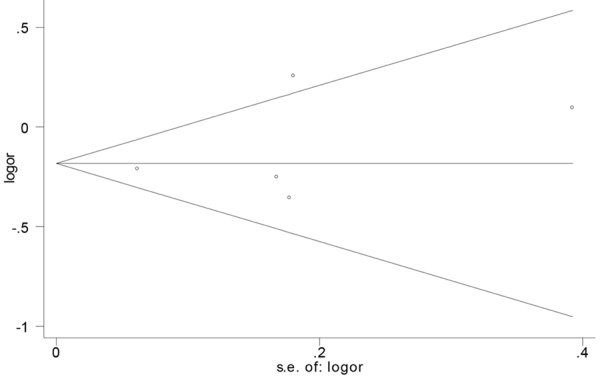

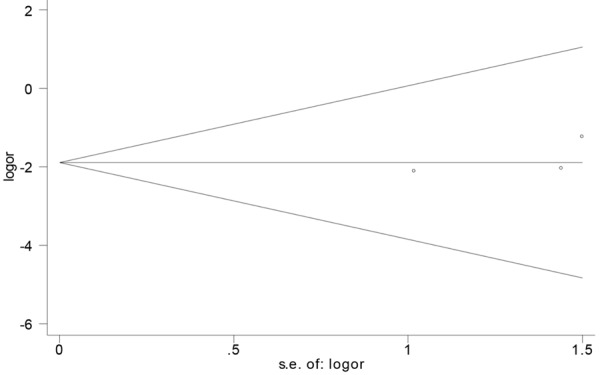

Publication bias

Publication bias was determined by Begg’s test and visualization of funnel plot. There was no evidence of publication bias for morbidity (P=0.462) (Figure 4) and mortality (P=0.296) (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Funnel plot of the RR of perioperative morbidity after RATS vs. OTS for lung cancer.

Figure 5.

Funnel plot of the RR of perioperative mortality after RATS vs. OTS for lung cancer.

Discussion

The first OTS for lung cancer using a thoracotomy incision was performed by H. Morriston Davies in 1912 [16]. Over a century later, OTS remains the most common technique to perform pulmonary lobectomies [17]. However, slow recovery and pain control requiring an epidural catheter or prolonged oral analgesics remain drawbacks to this approach [18]. In early 1990s, a minimally invasive approach VATS came into being and rapidly progressed to complex procedures of lung cancer, which is safe and feasible and results in fewer complications than OTS [2]. However, because of its 2D vision with lack of depth perception and the use of long rigid instruments in a counter intuitive manner, the adoption of this approach by thoracic surgeons remains low [7].

RATS, as a minimally invasive approach, may address many of the shortcomings of VATS and OTS [19]. RATS using the da Vinci system has been proposed as a viable minimally invasive surgery for lung cancer resection without sacrificing the familiar technical steps of the open technique [12,20]. It provides excellent 3D vision with magnification, a view even better than open surgery, and precise dissection with much improved surgeon ergonomics [11]. Robotic surgery in humans was first described by Cadiere and associates in 1997 [21]. The first case-series report on pulmonary resection by RATS was published in 2002, a number of studies have demonstrated the feasibility of this novel technique with encouraging results [22]. Today the commonest indication for robotic thoracic oncology is resection of mediastinal masses [23]. There are some publications on RATS for lung cancer reporting that RATS for lung cancer is feasible and safe [19,24,25].

Recently, a meta-analysis of only 532 participants from 2 comparative studies assessing perioperative morbidity outcomes identified a trend towards fewer complications after RVATS compared to OTS, but this difference was not statistically significance [26]. In the present study, our meta-analysis of over 2400 participants from 5 retrospective observational studies found significantly lower perioperative morbidity and mortality rate among patients with lung cancer who underwent RATS compared with those who underwent OTS. Thus, we suggest RATS be an appropriate alternative to OTS, which is associated with superior perioperative outcomes compared with OTS for lung cancer.

As far as we know, this is the most comprehensive meta-analysis to compare the perioperative morbidity and mortality outcomes of RATS with OTS for lung cancer. We made sure to minimize the bias by means of study procedure. Not only did we search Pubmed and Science direct to identify potential studies, but also we screened the reference lists of all relevant studies. Publication bias was absent as determined by Begg’s test. However, some limitations exist in the present systematic review. First, only 5 retrospective observational studies and no randomized clinical trial were included in the meta-analysis, thus the results should be interpreted with caution in view of a lack of randomized-controlled trials comparing RVATS to OTS. Second, patients’ baseline characteristics differed between studies, and there was inevitably some variability in the surgical techniques and skills of surgeons. Despite these limitations, our findings point out new direction for future research. We suggest that further study in a randomized fashion should be conducted to compare RATS with OTS to better define the potential advantages of the minimally invasive approaches for lung cancer.

In conclusion, the present meta-analysis demonstrated that RATS resulted in significantly lower perioperative morbidity and mortality rate compared with OTS cases. Thus, we suggest RATS be an appropriate alternative to OTS for lung cancer resection. In the absence of randomized controlled trials comparing RATS with OTS, our findings represent the highest level of clinical evidence in the current literature on this issue.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Bennett DT, Weyant MJ. The year in thoracic surgery: highlights from 2013. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2014;18:24–28. doi: 10.1177/1089253214521529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker WS, Carnochan FM, Pugh GC. Thoracoscopic pulmonary lobectomy. Early operative experience and preliminary clinical results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1993;106:1111–1117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higuchi M, Yaginuma H, Yonechi A, Kanno R, Ohishi A, Suzuki H, Gotoh M. Long-term outcomes after video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) lobectomy versus lobectomy via open thoracotomy for clinical stage IA non-small cell lung cancer. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;9:88. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-9-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuritzky AM, Ryder BA, Ng T. Long-term survival outcomes of Video-assisted Thoracic Surgery (VATS) lobectomy after transitioning from open lobectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:2734–2740. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-2929-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao C, Zhu ZH, Yan TD, Wang Q, Jiang G, Liu L, Liu D, Wang Z, Shao W, Black D, Zhao Q, He J. Video-assisted thoracic surgery versus open thoracotomy for non-small-cell lung cancer: A propensity score analysis based on a multi-institutional registry. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;44:849–854. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezt406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao C, Manganas C, Ang SC, Peeceeyen S, Yan TD. Video-assisted thoracic surgery versus open thoracotomy for non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis of propensity score-matched patients. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2013;16:244–249. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivs472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paul S, Altorki NK, Sheng S, Lee PC, Harpole DH, Onaitis MW, Stiles BM, Port JL, D’Amico TA. Thoracoscopic lobectomy is associated with lower morbidity than open lobectomy: A propensity-matched analysis from the STS database. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:366–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kent M, Wang T, Whyte R, Curran T, Flores R, Gangadharan S. Open, video-assisted thoracic surgery, and robotic lobectomy: review of a national database. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97:236–242. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.07.117. discussion 242-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park BJ, Flores RM. Cost comparison of robotic, video-assisted thoracic surgery and thoracotomy approaches to pulmonary lobectomy. Thorac Surg Clin. 2008;18:297–300. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melfi FM, Fanucchi O, Davini F, Romano G, Lucchi M, Dini P, Ambrogi MC, Mussi A. Robotic lobectomy for lung cancer: Evolution in technique and technology. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;46:626–630. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezu079. discussion 630-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veronesi G. Robotic lobectomy and segmentectomy for lung cancer: results and operating technique. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7:S122–130. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.04.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cerfolio RJ, Bryant AS, Skylizard L, Minnich DJ. Initial consecutive experience of completely portal robotic pulmonary resection with 4 arms. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;142:740–746. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deen SA, Wilson JL, Wilshire CL, Vallieres E, Farivar AS, Aye RW, Ely RE, Louie BE. Defining the cost of care for lobectomy and segmentectomy: a comparison of open, video-assisted thoracoscopic, and robotic approaches. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97:1000–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oh DS, Cho I, Karamian B, DeMeester SR, Hagen JA. Early adoption of robotic pulmonary lobectomy: feasibility and initial outcomes. Am Surg. 2013;79:1075–1080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veronesi G, Galetta D, Maisonneuve P, Melfi F, Schmid RA, Borri A, Vannucci F, Spaggiari L. Four-arm robotic lobectomy for the treatment of early-stage lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer JA. Hugh Morriston Davies and lobectomy for cancer, 1912. Ann Thorac Surg. 1988;46:472–474. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)64672-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gopaldas RR, Bakaeen FG, Dao TK, Walsh GL, Swisher SG, Chu D. Video-assisted thoracoscopic versus open thoracotomy lobectomy in a cohort of 13,619 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:1563–1570. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang B, Zhao F, Zong Z, Yuan J, Song X, Ren M, Meng Q, Dai G, Kong F, Xie S, Cheng S, Gao T. Preferences for treatment of lobectomy in Chinese lung cancer patients: video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery or open thoracotomy? Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8:1393–1397. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S68426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jang HJ, Lee HS, Park SY, Zo JI. Comparison of the early robot-assisted lobectomy experience to video-assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy for lung cancer: A single-institution case series matching study. Innovations (Phila) 2011;6:305–310. doi: 10.1097/IMI.0b013e3182378b4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park BJ, Flores RM, Rusch VW. Robotic assistance for video-assisted thoracic surgical lobectomy: technique and initial results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131:54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cadiere GB, Himpens J, Vertruyen M, Favretti F. The world’s first obesity surgery performed by a surgeon at a distance. Obes Surg. 1999;9:206–209. doi: 10.1381/096089299765553539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melfi FM, Menconi GF, Mariani AM, Angeletti CA. Early experience with robotic technology for thoracoscopic surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;21:864–868. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rea F, Marulli G, Bortolotti L, Feltracco P, Zuin A, Sartori F. Experience with the “da Vinci” robotic system for thymectomy in patients with myasthenia gravis: report of 33 cases. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:455–459. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Louie BE, Farivar AS, Aye RW, Vallieres E. Early experience with robotic lung resection results in similar operative outcomes and morbidity when compared with matched video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery cases. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:1598–1604. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.01.067. discussion 1604-1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swanson SJ, Miller DL, McKenna RJ Jr, Howington J, Marshall MB, Yoo AC, Moore M, Gunnarsson CL, Meyers BF. Comparing robot-assisted thoracic surgical lobectomy with conventional video-assisted thoracic surgical lobectomy and wedge resection: results from a multihospital database (Premier) J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;147:929–937. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao C, Manganas C, Ang SC, Yan TD. A systematic review and meta-analysis on pulmonary resections by robotic video-assisted thoracic surgery. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;1:3–10. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2012.04.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]