Abstract

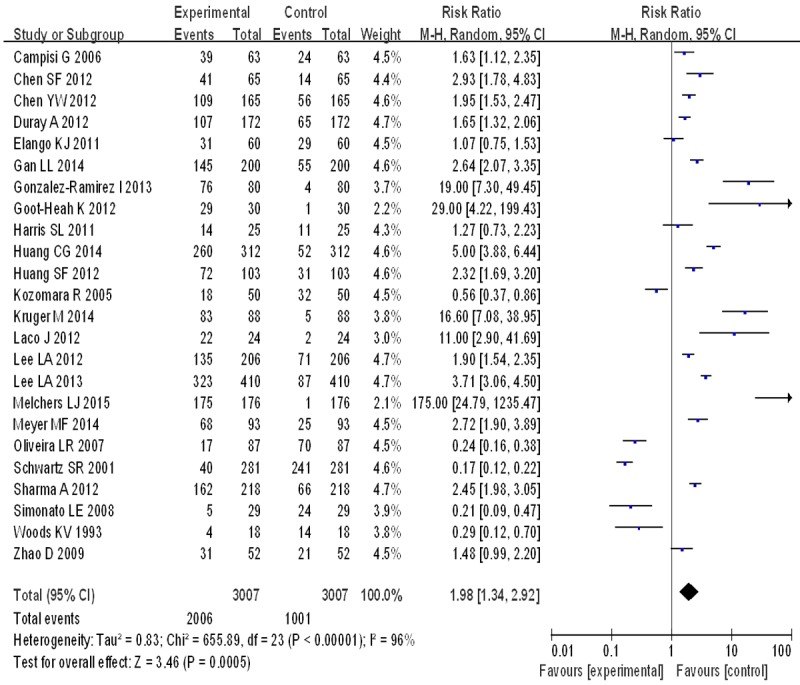

Previous studies indicated that oral squamous cell carcinomas (OSCC) might be related to human papilloma virus (HPV) infection. However, the relationship between OSCC in a Chinese population and oral HPV infection is still unclear. In this study, we evaluate the relationship of OSCC with HPV infection in a Chinese population via a meta-analysis. The reports on HPV and OSCC in a Chinese population published between January, 1994, and October, 2015 were retrieved via CNKI/WANFANG/pubmed databases. According to the inclusion criteria, we selected 26 eligible case-control studies. After testing the heterogeneity of the studies by the Cochran Q test, the meta-analyses for HPV and HPV16 were performed using the random effects model. Quantitative meta-analyses showed that, compared with normal oral mucosa the combined odds ratio of OSCC with HPV infection were 1.98 (95% CI: 1.34-2.92). The test for overall effect showed that the P value was less than 0.05 (Z = 3.46). Forest plot analyses were seen in Figures 2 and 3. Publication bias and bias risk analysis using RevMan 5.3 software were measured indicators of the graphics of the basic symmetry. High incidences of HPV infection were found in the samples of Chinese OSCC. For the Chinese population, HPV infection elevates the risk of OSCC tumorigenesis.

Keywords: Human papilloma virus, oral squamous cell carcinoma, Chinese

Introduction

HPV infection is a cause of nearly all cases of cervical cancer. In 1983, OSCC was firstly reported to be associated with HPV infection [28]. Afterwards, many studies showed that a different degree of relationship might exist between OSCC and HPV infection. It is possible that the risk difference of OSCC with HPV infection varies from different regions and different populations. Over 90% of all cervical cancers can be attributed to certain HPV types-HPV16 accounting for the largest proportion (roughly 50%) followed by HPV18 (12%), HPV 45 (8%), and HPV 31 (5%) [1]. Worldwide in 2002, an estimated 561,200 new cancer cases (5.2% of all new cancers) were attributable to HPV, suggesting that HPV is one of the most important infectious causes of cancer [2]. In recent years, some studies by Chinese researchers have also focused on the relationship between oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) and HPV oral infection.

However, the differences of the odds rates were reported in different literatures. Therefore, it is necessary to implement a meta-analysis which aims to comprehensively evaluate the relationship between OSCC and HPV oral infection in a Chinese population.

Methods

Search strategy

The keywords HPV, human papillomavirus, oral, oral cancer, head and neck cancer, tongue cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, oral carcinoma, buccal cancer, oral lesions, and Chinese population. The retrieved databases included China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI)/Wanfang Database/OVID/MEDLINE. Finally, a total of 401 citations published between Jun, 1994 and Oct, 2015 were identified.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The literatures included in the present study meets the following criteria: case-control studies; Chinese population; a diagnostic method was addressed and reliable. The literatures excluded in this study were mainly due to the following reasons: lacks of data needed; reviews. Of 401 publications identified through an initial search of databases and conference abstracts, 375 were excluded. A total of 26 literatures met the eligibility criteria were included in this present study.

Data extraction

The data related to this study were extracted by two independent reviewers. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus or in consultation with a third reviewer. The data related to this study were shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies investigating human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) and control samples

| First author | Year | Gender | HPV(-) | HPV(+) | Mean age | Country | Method | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| F | M | |||||||

| Huang CG [6] | 2014 | 16 | 296 | 260 | 52 | China | PCR | |

| Chen YW [7] | 2012 | 21 | 144 | 109 | 56 | 52 | China | Immunostaining |

| Huang SF [8] | 2012 | 7 | 96 | 72 | 31 | 49 | China | PCR |

| Simonato LE [9] | 2008 | 2 | 27 | 5 | 24 | 23 | Brazil | PCR |

| Oliveira LR [10] | 2007 | 14 | 73 | 17 | 70 | 54 | Brazil | PCR |

| Duray A [11] | 2012 | 32 | 130 | 44 | 65 | 57 | Belgium | PCR Immunohistchemistry |

| Zhao D [12] | 2009 | 17 | 35 | 21 | 21 | - | China | PCR |

| Schwartz SR [13] | 2001 | 90 | 163 | 40 | 214 | 54.2 | America | PCR |

| Lee LA [14] | 2012 | 7 | 156 | 135 | 71 | 51 | China | PCR |

| Metgud R [15] | 2012 | 72 | 156 | 162 | 66 | - | America | PCR |

| Elango KJ [16] | 2011 | 19 | 41 | 31 | 29 | 55 | India | PCR |

| Chen SF [17] | 2012 | 13 | 52 | 41 | 24 | 53 | China | In situ hybridization |

| Kruger M [18] | 2014 | 32 | 56 | 83 | 5 | - | Germany | PCR |

| Meyer MF [19] | 2014 | - | 68 | 25 | 57 | Germany | PCR | |

| Woods KV [20] | 1993 | 7 | 11 | 4 | 14 | 61 | America | PCR |

| Kozomara R [21] | 2005 | - | - | 18 | 32 | 32 | Yugoslavia | PCR |

| Gonzalez-Ramirez I [22] | 2013 | 46 | 34 | 76 | 4 | 63 | Mexico | PCR |

| Gan LL [23] | 2014 | 57 | 143 | 145 | 55 | 81 | China | PCR |

| Goot-Heah K [24] | 2012 | 21 | 9 | 29 | 1 | 30 | Malaysia | PCR |

| Harris SL [25] | 2011 | 15 | 10 | 14 | 11 | 30 | America | In situ hybridization (ISH) |

| Laco J [26] | 2012 | - | - | 22 | 2 | 63 | Hradec Kralove | PCR |

| Campisi G [27] | 2006 | 35 | 28 | 39 | 24 | 68.89 | Italy | PCR |

| Lee LA [28] | 2013 | 19 | 391 | 323 | 87 | 52 | China | In situ hydridisation |

| Melchers LJ [29] | 2015 | 70 | 106 | 175 | 1 | 63 | Netherlands | In situ hydridisation |

Data analysis

The dichotomous data of HPV positive results in OSCC group and normal control group was summarized. OR and 95% confidence interval [CI] of OR were calculated for assessing the association between HPV infection and OSCC risk. The analysis of the heterogeneity of between-study was performed using the Chi-square-based Q test [3]. A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant for the heterogeneity. If no heterogeneity, a fixed-effect model was applied using the Mantel-Haenszel method [4]. Otherwise, the random-effect model with the DerSimonian-Laird method [4] was used. The potential publication bias was assessed graphically by funnel plots [5]. The statistical analyses were performed using RevMan 5.3.

Results

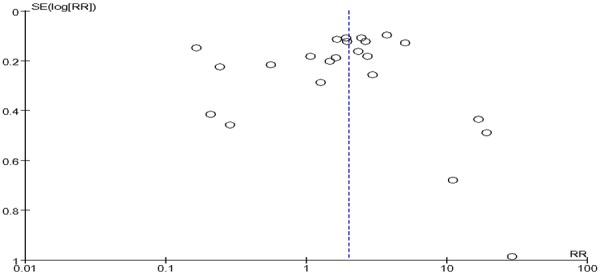

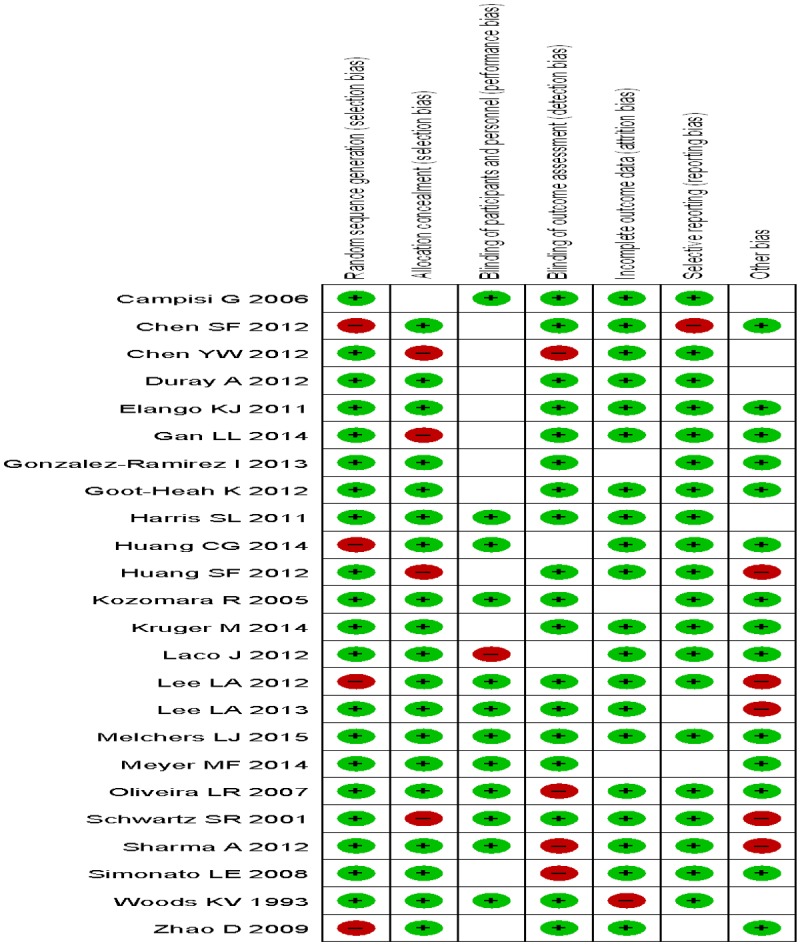

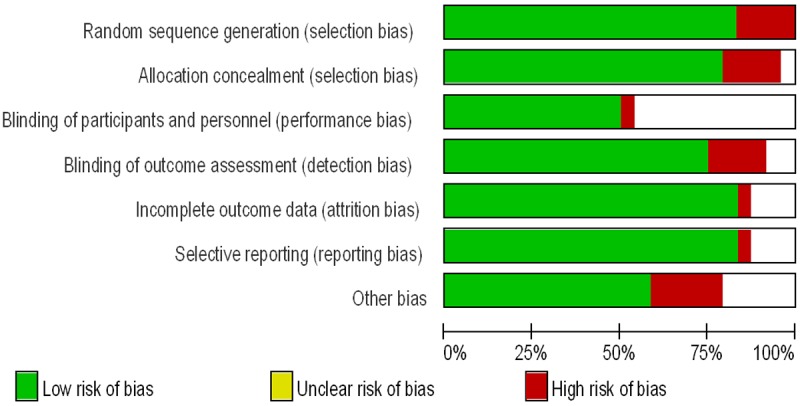

The mainly character of study included is showed in Table 1. Tests for the heterogeneity showed that, the Chi-square values were 655.89 (P<0.05). Therefore, a random-effect model was applied. Quantitative meta-analyses showed that, compared with normal oral mucosa the combined odds ratio of OSCC with HPV infection were 1.98 (95% CI: 1.34-2.92) (Figure 1). The test for overall effect showed that the P value was less than 0.05 (Z = 3.46). Forest plot analyses were seen in Figure 2. Publication bias and bias risk analysis using RevMan 5.3 software were measured indicators of the graphics of the basic symmetry (Figures 3, 4).

Figure 1.

Forest plots of the included studies of oral squamous cell carcinoma risk in HPV infection.

Figure 2.

Funnel plot of the included studies of oral squamous cell carcinoma risk in HPV infection.

Figure 3.

Risk of bias summary.

Figure 4.

Risk of bias graph.

Discussion

Quantitative meta-analyses showed that, compared with normal oral mucosa the combined odds ratio of OSCC with HPV infection were 1.98 (95% CI: 1.34-2.92). While another previous meta-analysis of the included literatures published in English-language journal between 1980 and 1998 revealed that [30], the likelihood of detecting HPV in normal oral mucosa (10.0%; 95% [CI], 6.1%-14.6%) was significantly less than that of OSCC (46.5%; 95% CI: 37.6%-55.5%), and the pooled odds ratio for the subset of studies directly comparing the prevalence of HPV in normal mucosa and OSCC was 5.4.

The previous reports showed that the patients with HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancers had a lower risk of dying or recurrence than do those with HPV-negative cancers [31-33]. The majority of studies showed than HPV-associated OSCC were associated with a better prognosis than HPV-negative tumors in the majority of studies [34,35]. Some researcher found that HPV-positive conferred a 60% to 80% reduction in risk of death from cancer compared with HPV-negative tumors [36]. Thus, HPV screening to the patients with OSCC is good for assessing the prognosis of OSCC. Prophylactic HPV-vaccination may reduce the burden of HPV-related OSCC in China.

In present study, the funnel plots of included studies showed that, the graphics is basically symmetric and all points is concentrated in the central funnel, indicating that no publication bias was found in this study. Additionally, the present study also has some shortcoming. Most of the literatures included the present study didn’t control confounding factors, because gender, age, and lifestyle have a big influence on the relationship between OSCC with HPV infection. Moreover, tumor location, clinical stage and degree of differentiation also have some degree of effect on the association mentioned above. Considering that HPV infection plays an important role in tumorigenesis of OSCC, more scientific studies should be included for meta-analysis in future research.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Provincial Natural Science Research Project of Anhui Colleges (No. KJ2014A269).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Muñoz N, Bosch FX. The causal link between HPV and cervical cancer and its implications for prevention of cervical cancer. Bull Pan Am Health Organ. 1996;30:362–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkin DM. The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year 2002. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:3030–44. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22:719–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Irwig L, Macaskill P, Berry G, Glasziou P. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Graphical test is itself biased. BMJ. 1998;316:470. author reply 470-1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang CG, Lee LA, Tsao KC, Liao CT, Yang LY, Kang CJ, Chang KP, Huang SF, Chen IH, Yang SL, Lee LY, Hsueh C, Chen TC, Lin CY, Fan KH, Chang TC, Wang HM, Ng SH, Yen TC. Human papillomavirus 16/18 E7 viral loads predict distant metastasis in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Virol. 2014;61:230–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen YW, Chen IL, Lin IC, Kao SY. Prognostic value of hypercalcaemia and leucocytosis in resected oral squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;52:425–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2014.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang SF, Li HF, Liao CT, Wang HM, Chen IH, Chang JT, Chen YJ, Cheng AJ. Association of HPV infections with second primary tumors in early-staged oral cavity cancer. Oral Dis. 2012;18:809–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2012.01950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simonato LE, Garcia JF, Sundefeld ML, Mattar NJ, Veronese LA, Miyahara GI. Detection of HPV in mouth floor squamous cell carcinoma and its correlation with clinicopathologic variables, risk factors and survival. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37:593–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oliveira LR, Ribeiro-Silva A, Zucoloto S. Prognostic significance of p53 and p63 immunolocalisation in primary and matched lymph node metastasis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Acta Histochem. 2007;109:388–96. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duray A, Descamps G, Decaestecker C, Remmelink M, Sirtaine N, Lechien J, Ernoux-Neufcoeur P, Bletard N, Somja J, Depuydt CE, Delvenne P, Saussez S. Human papillomavirus DNA strongly correlates with a poorer prognosis in oral cavity carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:1558–65. doi: 10.1002/lary.23298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao D, Xu QG, Chen XM, Fan MW. Human papillomavirus as an independent predictor in oral squamous cell cancer. Int J Oral Sci. 2009;1:119–25. doi: 10.4248/IJOS.09015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwartz SR, Yueh B, McDougall JK, Daling JR, Schwartz SM. Human papillomavirus infection and survival in oral squamous cell cancer: a population-based study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:1–9. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2001.116979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee LA, Huang CG, Liao CT, Lee LY, Hsueh C, Chen TC, Lin CY, Fan KH, Wang HM, Huang SF, Chen IH, Kang CJ, Ng SH, Yang SL, Tsao KC, Chang YL, Yen TC. Human papillomavirus-16 infection in advanced oral cavity cancer patients is related to an increased risk of distant metastases and poor survival. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40767. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Metgud R, Astekar M, Verma M, Sharma A. Role of viruses in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rev. 2012;6:e21. doi: 10.4081/oncol.2012.e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elango KJ, Suresh A, Erode EM, Subhadradevi L, Ravindran HK, Iyer SK, Iyer SK, Kuriakose MA. Role of human papilloma virus in oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:889–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen SF, Yu FS, Chang YC, Fu E, Nieh S, Lin YS. Role of human papillomavirus infection in carcinogenesis of oral squamous cell carcinoma with evidences of prognostic association. J Oral Pathol Med. 2012;41:9–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2011.01046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krüger M, Pabst AM, Walter C, Sagheb K, Günther C, Blatt S, Weise K, Al-Nawas B, Ziebart T. The prevalence of human papilloma virus (HPV) infections in oral squamous cell carcinomas: a retrospective analysis of 88 patients and literature overview. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2014;42:1506–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2014.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyer MF, Seuthe IM, Drebber U, Siefer O, Kreppel M, Klein MO, Mikolajczak S, Klussmann JP, Preuss SF, Huebbers CU. Valosin-containing protein (VCP/p97)-expression correlates with prognosis of HPV- negative oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) PLoS One. 2014;9:e114170. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woods KV, Shillitoe EJ, Spitz MR, Schantz SP, Adler-Storthz K. Analysis of human papillomavirus DNA in oral squamous cell carcinomas. J Oral Pathol Med. 1993;22:101–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1993.tb01038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kozomara R, Jović N, Magić Z, Branković-Magić M, Minić V. p53 mutations and human papillomavirus infection in oral squamous cell carcinomas: correlation with overall survival. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2005;33:342–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.González-Ramírez I, Irigoyen-Camacho ME, Ramírez-Amador V, Lizano-Soberón M, Carrillo-García A, García-Carrancá A, Sánchez-Pérez Y, Méndez-Martínez R, Granados-García M, Ruíz-Godoy L, García-Cuellar C. Association between age and high-risk human papilloma virus in Mexican oral cancer patients. Oral Dis. 2013;19:796–804. doi: 10.1111/odi.12071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gan LL, Zhang H, Guo JH, Fan MW. Prevalence of human papillomavirus infection in oral squamous cell carcinoma: a case-control study in Wuhan, China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:5861–5. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.14.5861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goot-Heah K, Kwai-Lin T, Froemming GR, Abraham MT, Nik Mohd Rosdy NM, Zain RB. Human papilloma virus 18 detection in oral squamous cell carcinoma and potentially malignant lesions using saliva samples. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:6109–13. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.12.6109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris SL, Thorne LB, Seaman WT, Hayes DN, Couch ME, Kimple RJ. Association of p16(INK4a) overexpression with improved outcomes in young patients with squamous cell cancers of the oral tongue. Head Neck. 2011;33:1622–7. doi: 10.1002/hed.21650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laco J, Nekvindova J, Novakova V, Celakovsky P, Dolezalova H, Tucek L, Vosmikova H, Vosmik M, Neskudlova T, Cermakova E, Hacova M, Sobande FA, Ryska A. Biologic importance and prognostic significance of selected clinicopathological parameters in patients with oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, with emphasis on smoking, protein p16(INK4a) expression, and HPV status. Neoplasma. 2012;59:398–408. doi: 10.4149/neo_2012_052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campisi G, Giovannelli L, Calvino F, Matranga D, Colella G, Di Liberto C, Capra G, Leao JC, Lo Muzio L, Capogreco M, D’Angelo M. HPV infection in relation to OSCC histological grading and TNM stage. Evaluation by traditional statistics and fuzzy logic model. Oral Oncol. 2006;42:638–45. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee LA, Huang CG, Tsao KC, Liao CT, Kang CJ, Chang KP, Huang SF, Chen IH, Fang TJ, Li HY, Yang SL, Lee LY, Hsueh C, Chen TC, Lin CY, Fan KH, Wang HM, Ng SH, Chang YL, Lai CH, Shih SR, Yen TC. Increasing rates of low-risk human papillomavirus infections in patients with oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma: association with clinical outcomes. J Clin Virol. 2013;57:331–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melchers LJ, Mastik MF, Samaniego Cameron B, van Dijk BA, de Bock GH, van der Laan BF, van der Vegt B, Speel EJ, Roodenburg JL, Witjes MJ, Schuuring E. Detection of HPV-associated oropharyngeal tumours in a 16-year cohort: more than meets the eye. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:1349–57. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller CS, Johnstone BM. Human papillomavirus as a risk factor for oral squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis, 1982-1997. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;91:622–35. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.115392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, Weber R, Rosenthal DI, Nguyen-Tân PF, Westra WH, Chung CH, Jordan RC, Lu C, Kim H, Axelrod R, Silverman CC, Redmond KP, Gillison ML. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Settle K, Posner MR, Schumaker LM, Tan M, Suntharalingam M, Goloubeva O, Strome SE, Haddad RI, Patel SS, Cambell EV 3rd, Sarlis N, Lorch J, Cullen KJ. Racial survival disparity in head and neck cancer results from low prevalence of human papillomavirus infection in black oropharyngeal cancer patients. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2009;2:776–81. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ragin CC, Taioli E. Survival of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck in relation to human papillomavirus infection: review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:1813–20. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gillison ML, Koch WM, Capone RB, Spafford M, Westra WH, Wu L, Zahurak ML, Daniel RW, Viglione M, Symer DE, Shah KV, Sidransky D. Evidence for a causal association between human papillomavirus and a subset of head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:709–20. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.9.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Licitra L, Perrone F, Bossi P, Suardi S, Mariani L, Artusi R, Oggionni M, Rossini C, Cantù G, Squadrelli M, Quattrone P, Locati LD, Bergamini C, Olmi P, Pierotti MA, Pilotti S. High-risk human papillomavirus affects prognosis in patients with surgically treated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006;24:5630–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.6136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weinberger PM, Yu Z, Haffty BG, Kowalski D, Harigopal M, Brandsma J, Sasaki C, Joe J, Camp RL, Rimm DL, Psyrri A. Molecular classification identifies a subset of human papillomavirus--associated oropharyngeal cancers with favorable prognosis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006;24:736–47. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.3335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]