Abstract

This article focuses on stability and change in “mixed middle-income” neighborhoods. We first analyze variation across nearly two decades for all neighborhoods in the United States and in the Chicago area, particularly. We then analyze a new longitudinal study of almost 700 Chicago adolescents over an 18-year span, including the extent to which they are exposed to different neighborhood income dynamics during the transition to young adulthood. The concentration of income extremes is persistent among neighborhoods, generally, but mixed middle-income neighborhoods are more fluid. Persistence also dominates among individuals, though Latino-Americans are much more likely than African Americans or whites to be exposed to mixed middle-income neighborhoods in the first place and to transition into them over time, even when adjusting for immigrant status, education, income, and residential mobility. The results here enhance our knowledge of the dynamics of income inequality at the neighborhood level, and the endurance of concentrated extremes suggests that policies seeking to promote mixed-income neighborhoods face greater odds than commonly thought.

Keywords: mixed-income neighborhoods, inequality, young adulthood, life course

Increases in income segregation, combined with the apparent loss of middle-class and mixed-income neighborhoods, have generated considerable attention. Among scholars and the public at large, recent attention has been focused primarily on the pulling away of the very rich—the so-called 1 percent (Piketty 2014). At the other end, a classic urban literature has produced a wealth of studies on concentrated poverty and the “truly disadvantaged” (Wilson 1987).1

Mixed-income housing has become a major policy paradigm that seeks to address such income extremes. Based on evidence that links concentrated poverty to compromised life outcomes, federal policy-makers in the United States have advocated moving poor people out of concentrated public housing and increasing the presence of higher-income neighbors through mixed-income redevelopment of high-poverty neighborhoods. Two examples of these arguments are the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)’s “Moving to Opportunity” voucher experiment, which sought to move the poor out of concentrated poverty; and HOPE VI, a place-based intervention that sought to increase income mixing in housing developments. With Mayor Bill de Blasio in New York City as the foremost example, city leaders around the country have also taken aim at policies to reduce residential inequality.2

Although neighborhood income mixing has surfaced as a favored policy tool and is the subject of growing scholarly discussion, research evaluating its sources and consequences is sparse. As a result, less is known about the nature of middle-income and mixed-income neighborhoods, and the experience of individuals transitioning into and out of the middle, rather than the extremes. The evidence that does exist has produced conflicting results (Joseph and Chaskin 2012), and much of the writing about mixed-income neighborhoods is normative or aspirational rather than analytic (Cisneros and Engdahl 2009). There are also important untested assumptions and unanswered questions about neighborhood change (Joseph, Chaskin, and Webber 2007). For example, if a neighborhood is middle or working class and a mixed-income housing intervention brings lower-income residents in, it is an open question whether the intervention would lead over time to the out-migration of existing middle-class residents or decreases in the in-migration of the nonpoor. More generally, mixed-income policy implicitly assumes a kind of static equilibrium with regard to intervention effects. Equally important is the fact that proportionately few people live in planned mixed-income housing or HOPE VI neighborhoods. Like ethnically diverse communities (Ellen 2000), mixed-income neighborhoods that are “naturally occurring” are much more common, and yet we do not know much about their course of development—for individuals or at the neighborhood level.

Framework and Research Approach

This article focuses on the dynamics of what might best be characterized as “mixed middle-income” neighborhoods: areas that are more evenly balanced than those at the extremes of either concentrated poverty or concentrated affluence and that have a reasonable mix among income groups, especially exposure of the poor to the middle and upper classes. Studying individual sorting and population flows into and out of mixed middle-income neighborhoods is fundamental to understanding neighborhood income inequality and, we argue, analytically necessary prior to assessing the impact of such neighborhoods on outcomes, whether at the individual or neighborhood level (see also Bruch and Mare 2006; Sampson and Sharkey 2008). We therefore analyze variation in mixed middle-income neighborhoods at both the neighborhood and individual levels, placing our emphasis on patterns of stability and change.

We begin by defining and validating a measure of mixed-income neighborhoods; we then examine neighborhood-level transitions over the course of several decades. Although neighborhoods are constantly in flux, the evidence on the persistence of neighborhood poverty (Sampson 2012) leads to the hypothesis that mixed-income neighborhoods tend to occupy similar positions in the citywide distribution over time. However, gentrification and the demolition of public housing in cities such as Chicago may have altered this pattern. For example, are economically integrated neighborhoods stable, or merely in transition between low-income and high-income areas?

We focus on income mixing that is organic or “naturally occurring” in the sense that neighborhood income status is not defined based on local or federal housing policy interventions. There are good reasons for this analytic move. In Chicago, our study site and a city of more than 2.7 million residents and a million housing units, we estimate that less than 5 percent of city residents live in a census tract where a public housing project is located. If we restrict our concern to HUD’s HOPE VI housing program, the total number of units in mixed-income developments under the city’s “Plan for Transformation” is about 12,000, approximately 1 percent of all housing units. Moreover, the effort to provide new subsidized housing units has stalled (Moore 2013), and in fiscal year 2014, only about 2,600 mixed-income units were leased.

The prevalence and correlates of moving in and out of naturally occurring mixed-income neighborhoods therefore looms large and motivates the second and major part of our article. Here we focus on individual exposure to neighborhood income mixing, based on a new longitudinal survey of almost 700 adolescents originally living in Chicago in 1995 and followed wherever they moved in the United States, with the most recent data collection ending in 2013. The study consists of a birth cohort followed up to 17 years of age and three later cohorts (ages 9–15) that were studied into young adulthood. Our central aim is to describe trajectories of neighborhood attainment for the young adult cohorts. They are of primary interest because we know the income status of both the neighborhood that their parents chose when respondents were children and the neighborhood that our respondents chose, or ended up in, during the critical transition to young adulthood (ages 25–32), which allows for an intergenerational perspective on neighborhood attainment. By contrast, the birth cohort members have not left their parents’ home.

We first present descriptive patterns on trajectories of neighborhood mobility—how much stability or change is there in exposure to mixed-income areas? We focus primarily on race, cohort, and immigrant status as conditioning factors. Based on prior research, we expect that blacks and Latinos are disproportionately exposed to poverty compared with whites. However, we do not know how different racial/ethnic groups are exposed to mixed middle-income neighborhoods over time. Nor do we know if race/ethnic differences are attributable to preexisting differences in factors such as economic status or homeownership, or to time-varying factors such as residential mobility. Our last set of analyses thus examines the predictors of transitioning into mixed middle-income neighborhoods over young adulthood using a core set of theoretically selected characteristics.

The Mixed-Income Project

The larger project in which this study is embedded is the Mixed-Income Project (MIP), which was designed to examine neighborhood context, residential mobility, and mixed-income housing in Chicago and Los Angeles. The two anchor studies that formed the backbone of MIP are the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN) and the Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey (LAFANS). The PHDCN and LAFANS are widely recognized for rich longitudinal data on neighborhoods and on educational, health, and behavioral outcomes. For present purposes, we focus on the city of Chicago and the PHDCN.

Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN)

The PHDCN is a longitudinal cohort study of 6,207 children and their caregivers based on a representative sample drawn from eighty neighborhood clusters (NCs) in Chicago in 1995. A two-stage sampling procedure was conducted. U.S. census data were first used to identify 343 NCs in the city of Chicago: groups of two to three census tracts containing approximately 8,000 people that were relatively homogeneous with respect to racial/ethnic mix, socioeconomic status, housing density, and family structure. From these, a random sample of 80 of the 343 NCs was drawn within twenty-one strata defined by racial/ethnic composition (seven categories) and SES (socioeconomic status: high, medium, and low).

Second, within the sampled eighty NCs, children falling within seven age cohorts (0 [birth], 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18) were sampled from randomly selected households based on a screening of more than 35,000 households. Dwelling units were selected systematically from a random start within enumerated blocks. Within dwelling units, all households were listed, and all age-eligible children were selected with certainty. Multiple siblings were thus interviewed within some households. At baseline, the resulting PHDCN sample was 16 percent European American, 35 percent African American, and 43 percent Latino, evenly split by gender, and representative of families living in a wide range of Chicago neighborhoods.

Extensive in-home interviews and assessments were conducted with the sampled children and their primary caregivers three times over a 7-year period, at roughly 2.5-year intervals (wave 1 in 1995–1997, wave 2 in 1997–1999, and wave 3 in 1999–2001). Participants were followed no matter where they moved in the United States. Participation at baseline and retention at wave 3 were relatively high for a contemporary urban sample, 78 percent and 75 percent, respectively.

MIP research design

The MIP follow-up located and reinterviewed randomly sampled participants last contacted at wave 3 of PHDCN in the original birth cohort (now about age 16–17) and the age 9–15 cohorts (now 26–32). These cohorts were selected to maximize variation in life-course experiences and because the age 18 cohort had the highest attrition rate at wave 3, and the MIP pilot test indicated that the age 3 and 6 cohorts were most difficult to locate. The Chicago field operation engaged in a multimethod tracking effort using electronic, phone-based, and in-person methods (e.g., knocking on doors). The majority of interviews were carried out in person (almost 60 percent), but phone interviews were allowed if preferred by respondents or easier to implement. Despite the long time that elapsed since last contact at wave 3 and the contemporary big-city setting, MIP achieved a final response rate in the Chicago Main Study of 63 percent of eligible cases overall, yielding 1,057 respondents (40 percent Latino, 37 percent black, and 19 percent white).

For this article, we examine the 226, 236, and 217 respondents in the 9-, 12-, and 15-year old cohorts, respectively. These respondents spent their early years of development in an era that included the violence epidemic and severe urban challenges in Chicago, entered young adulthood during the widespread crime decline, and then experienced their late 20s and early 30s in the era of the Great Recession. To capture exposure to neighborhood income mixing over this time span, we geo-coded addresses of the MIP sample to census tract boundaries and merged them with waves 1–3 of the PHDCN. Each individual was thus linked to a census tract for each of the four waves of the combined PHDCN-MIP survey.3 We then integrated census data across three decades and the American Community Survey (ACS) data from 2005–9, 2006–10, 2007–11, and 2008–12.

Mixed in the Middle

A clear definition or consensus on measures of mixed-income neighborhoods is noticeably absent in past research, in part because income mixing and income inequality within neighborhoods are closely related yet distinct concepts. One way to think about income mixing is to focus solely on measures of income dispersion, but high values of inequality can be generated at the extremes of the neighborhood income distribution. For example, the Gini Index of income inequality, available in the ACS for 2007–11, is highest in the poorest and richest census tracts, defined according to the lowest and highest quintiles of median income. This is not surprising, as there are very low and high incomes that stretch the distribution. But having a lot of variation at the high end is not what we would typically consider a desired outcome, at least in the world of mixed-income housing. A pragmatic mixed-income policy seeks to expose the poor to middle-class society—going from poverty to the “Upper East Sides” of the world is neither realistic nor necessarily desirable. It is thus hard to achieve a meaningful measure of mixed income absent a simultaneous focus on the level of income or where in the distribution a neighborhood is located.

After exploring multiple indicators of inequality and diversity, in addition to more traditional indicators of concentrated poverty and median income, we follow Massey (2001) by focusing on simplicity and clear metrics in defining the Index of Concentration at the Extremes (ICE) as , where A is the number of affluent residents in neighborhood i, P is the number of poor residents in neighborhood i, and T is the total number of residents in neighborhood i. The ICE can theoretically range from −1 (where all residents are poor) to 1 (where all residents are affluent). Relatively greater income mixing, in the form of an even balance of poor and affluent residents, is centered at 0. Operationally, we calculate the ICE using the national upper- and lower-income quintiles of family income as the cutoffs for affluent and poor families, respectively, assigning an ICE score for each year from 1990 to 2010 (using interpolation) at the census tract–level in the Chicago area and for all neighborhoods in the United States. In addition to its clearly interpretable definition, the ICE controls for shifting income distributions over time.

The ICE classification is desirable because it focuses directly on income extremes, but it has potential limitations in distinguishing mixed-income areas from purely homogenous middle-class areas. We therefore explored additional definitions of mixed-income neighborhoods using the Herfindahl index of income diversity, the Gini Index of income inequality, and the Interquartile Range (IQR) of income for each tract based on household income bins. The Herfindahl index is defined as , where income bins were based on quintiles. The Herfindahl index ranges from 0, indicating everyone living in the neighborhood is in just one income category, to 1, indicating complete evenness across categories. The range of the index is limited by the number of categories used: with 5 categories, the index’s maximum value is 0.8.

Analysis of the Herfindahl index shows that the highest level of income diversity is in the mixed-income category of the ICE, indicating convergent validity. Also, as expected, the IQR is much higher in the middle category of the classification (where the ICE centers on 0) than in the low-income category, whereas the largest IQR (i.e., the largest absolute difference in 25th and 75th percentile of incomes) is driven by the extremely high incomes found in the upper 20 percent of the ICE, which denotes concentrated affluence. As noted earlier, the Gini Index is highest in the upper and lower fifths of neighborhood median income (.46) compared with the middle category (.41).4 At least in American society, it thus appears that the greatest exposure to mixed-income populations—especially among the poor or near poor—is found in the middle of the neighborhood ICE distribution, which also favors more equality.

To further explore this argument, we examined the observed amount of income mixing in our individual-level MIP sample according to the ICE classification. To do so, we defined each MIP respondent in wave 1 by the quintile of household income and then compared the distribution of the sample across the quintiles of neighborhood ICE. The greatest income mix whereby individual poor residents are exposed to upper-income residents in roughly equal proportions is in our category of mixed middle-income, compared with more affluent or poverty areas. For example, 19 percent of MIP residents in the middle ICE category are low-income (lowest category of household income), compared with 17 percent affluent (highest category of household income)—a gap of just 2 percent. Every other ICE category has larger gaps—especially, not surprisingly, the lowest and highest categories of the ICE, where the absolute gaps are 37 and 43 percent, respectively. But even in ICE categories 2 and 4, the gaps are considerably higher: 26.2 and 9.1, respectively. We also calculated Herfindahl indices. Consistent with the above analysis, the highest level of income diversity is in category 3 of the ICE, at .79. Like the neighborhood level analysis for the United States and for Chicago Cook County, then, our individual-level sample validates the mixed middle-income classification.

Neighborhood-Level Results

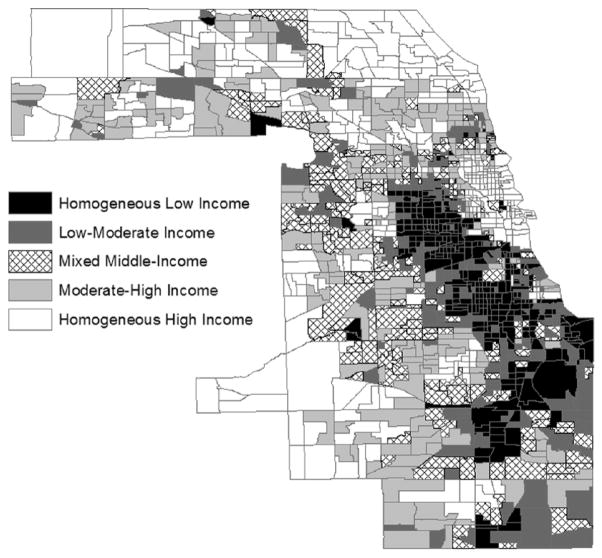

Figure 1 shows the ICE distribution in Chicago’s Cook County, where more than 80 percent of our sample remained during the follow-up. The map is based on quintiles, corresponding to the five labeled neighborhood types, ranging from “homogenous low income” to “homogeneous high income.” The ACS estimates from 2008–12 reveal that 20 percent of family households earned less than $27,000 per year, and 81 percent earned less than $116,000 per year (in 2011 dollars). We used these income thresholds to define poor and affluent households for computing the ICE for an examination of current income distributions. In Cook County, the ICE ranges from −0.85 to 0.70. The map illustrates the spatial variability in income mixing across neighborhoods. Some 18 percent of tracts in Cook County are mixed income, and approximately 16 percent of the overall Chicago sample lives in the mixed middle-income category.

FIGURE 1.

Mixed-Income Classification in Chicago and Cook County, 2008–12

Are economically integrated neighborhoods stable or merely in transition between relatively homogenous high- (or low) and low- (or high) income areas? The process of gentrification suggests a directional shift from lower to higher income areas, whereas a neighborhood decline narrative suggests the reverse. An inspection of Figure 1 suggests that mixed-income areas in Chicago are more proximate to homogenously poor areas on the city’s South and West sides than to homogenously affluent areas, suggesting the potential fragility of mixed-income neighborhoods over time.

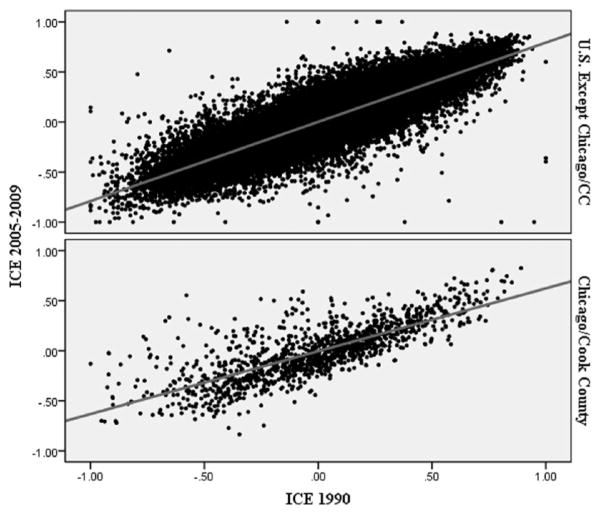

We assess neighborhood dynamics in Figure 2 by displaying the relationship between the ICE indicator in 1990 and 2005–9 for all census tracts in both Chicago/Cook County and the rest of the United States (N = ~ 64,000). There is a high degree of persistence revealed in both graphs, especially at the high end, with areas of concentrated affluence largely remaining affluent. Chicago is thus not unique, and if anything, the persistence of income extremes is higher outside the Chicago area. For non-Chicago/Cook County tracts, the Pearson’s and Spearman’s rank-order correlations are very high—.87 and .86, respectively. Chicago comes in lower but still high, at.77 and .78. There is also suggestive evidence of gentrification in the Chicago area—note the areas above the regression line in the upper left quadrant of Figure 2, which represent poor neighborhoods that became more mixed income or affluent over time. Hwang and Sampson (2014) analyzed gentrification trajectories in Chicago and found that among neighborhoods that showed initial signs of gentrification in 1995 or that were nearby one another, trajectories of gentrification through 2009 were lower in areas with higher shares of blacks and Latinos—even after accounting for characteristics such as crime, poverty, and proximity to amenities.

FIGURE 2.

ICE by Year, Chicago/Cook County and the Rest of the United States (N=63,709 Census Tracts with 500 or More Population in 1990 and 2000)

Although there is some evidence of upgrading and probably gentrification in areas that were largely poor, the overall correlations and transition matrices indicate that “stickiness” is the general rule. Indeed, the correlation of ICE over a 19-year time span exceeds .75 in both Chicago and the entire country, and in both settings the majority of neighborhoods that are in the top or bottom quintiles of income remain there. These patterns exist despite that inequality has been increasing at the top end (Reardon and Bischoff 2011)—the increase in the prevalence of rich neighborhoods does not override the strong inertial tendency of tracts to remain in a similar relative position over time.5

In Table 1 we look at population data from the Chicago area another way in the form of a transition matrix from 1990 to 2005–9 for quintiles of neighborhood ICE. Again we see evidence of greater persistence over time among neighborhoods at the extremes, with 65 percent or more of poor (lowest quintile) and affluent (highest quintile) neighborhoods remaining in the same category, compared with less than 30 percent of mixed middle-income neighborhoods. For the United States as a whole not counting the Chicago area, persistence is even greater—for example, 75 percent of affluent neighborhoods in 1990 remain affluent in 2007 and almost 70 percent of poor areas remain so.

TABLE 1.

Neighborhood-Level Transitions in the ICE, Chicago/Cook County (N=1,264 Census Tracts, 1990 to 2005–9)

| 2005–9 | 1990 ICE Quintiles

|

Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| ICE Quintiles | ||||||

| 1 | 201 | 47 | 21 | 3 | 0 | 272 |

| 66.34 | 30.72 | 10.66 | 1.02 | 0 | 21.52 | |

| 2 | 45 | 49 | 76 | 28 | 1 | 199 |

| 14.85 | 32.03 | 38.58 | 9.52 | 0.32 | 15.74 | |

| 3 | 24 | 34 | 59 | 101 | 14 | 232 |

| 7.92 | 22.22 | 29.95 | 34.35 | 4.42 | 18.35 | |

| 4 | 23 | 12 | 27 | 133 | 94 | 289 |

| 7.59 | 7.84 | 13.71 | 45.24 | 29.65 | 22.86 | |

| 5 | 10 | 11 | 14 | 29 | 208 | 272 |

| 3.3 | 7.19 | 7.11 | 9.86 | 65.62 | 21.52 | |

| Total | 303 | 153 | 197 | 294 | 317 | 1,264 |

| 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

These aggregate-level findings suggest that mixed-income neighborhoods are closely connected to larger structures of urban inequality. They also suggest that within the current structures that we observed, inducing large changes in exposure to neighborhood income mixing will likely result from individual mobility into and out of neighborhoods, rather than from changes within neighborhoods for persons who do not move. This is not to say neighborhoods do not change; clearly they do, and gentrification is real. But when we do not select on change and instead observe the universe of all neighborhoods either locally or nationally, we see strong evidence of the relative persistence of neighborhood position with respect to income.

Individual-Level Transitions and Trajectories in Chicago

The preceding analyses lead us to now consider individual-level trajectories of neighborhood income attainment. We ask, for example, how much change is there over time in the exposure of study participants to different income contexts, such as the transition from a poor neighborhood to a mixed-income or even affluent neighborhood? What is the profile of individuals who move into mixed middle-income neighborhoods over the life course of young adulthood? Is living in mixed-income areas a transitory state?

We begin with a transition matrix of individual exposure to concentrated poverty, concentrated affluence, and mixed middle-income neighborhoods over roughly an 18-year period (1995 to early 2013). Because we focus on the 9-, 12-, and 15-year-old cohorts, in effect we examine the transition from one’s neighborhood in adolescence (of parental choice) to the destination neighborhood in young adulthood (the study participant’s choice). As before, the neighborhood income measure is based on quintiles, but because study participants were free to move anywhere outside Chicago, we use national income distributions from 2012 to define the ICE quintiles.6 These prevalence data and all analyses to follow are weighted to account for the stratified sample design at wave 1 and for potential attrition bias over time in the follow up.7

The results in Table 2 demonstrate that there is considerable inertia in the residential exposure of our sample at the low and high values of the ICE. Indeed, despite that there are five income categories, fully 61 percent of respondents who live in neighborhoods in the lowest ICE quintile at wave 1 remain in neighborhoods in the lowest ICE quintile almost two decades later at wave 4: in this sense, concentrated poverty exposure is durable. At the affluent extreme, just over 41 percent of respondents who live in neighborhoods in the top 20 percent of the ICE distribution at wave 1 remain there at wave 4 and another 34 percent end up in the next lowest category; thus only about a quarter of this group was significantly downwardly mobile.

TABLE 2.

Individual-Level Transitions in the ICE, Chicago Young-Adult Sample (N=671 Individuals, 1995–2013)

| Wave 4 | Wave 1 ICE Quintiles

|

Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| ICE Quintiles | ||||||

| 1 | 140 | 50 | 30 | 6 | 4 | 229 |

| 60.56 | 34.42 | 18.89 | 5.66 | 11.08 | 34.14 | |

| 2 | 53 | 35 | 46 | 18 | 2 | 155 |

| 23.17 | 24.36 | 29.27 | 17.5 | 6.24 | 23.06 | |

| 3 | 23 | 36 | 33 | 15 | 3 | 109 |

| 9.96 | 24.65 | 20.76 | 14.79 | 7.76 | 16.27 | |

| 4 | 9 | 14 | 26 | 35 | 12 | 97 |

| 3.99 | 9.73 | 16.69 | 34.61 | 33.53 | 14.46 | |

| 5 | 5 | 10 | 23 | 28 | 15 | 81 |

| 2.32 | 6.84 | 14.39 | 27.45 | 41.39 | 12.07 | |

| Total | 231 | 145 | 157 | 101 | 37 | 671 |

| 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

By contrast, considerable fluidity characterizes the middle of the distribution. Based on our earlier analysis, we define mixed-income neighborhoods as those falling between the second and third quintile of the ICE. Higher shares of respondents living in mixed-income neighborhoods at wave 1 experience a change in neighborhood income mix by wave 4 than do respondents who live in more homogenous lower or higher income neighborhoods at wave 1. We see this pattern from the fairly even distribution of values in the column corresponding to residence in ICE category 3 at wave 1. The values in this column are more similar to each other than the values in other ICE quintile columns. In fact, only 21 percent of respondents who live in mixed-income neighborhoods at wave 1 remain in mixed-income neighborhoods at wave 4. This percentage is considerably lower than the share of respondents who start and end in more homogenous lower- or higher-income neighborhoods; continuous exposure to mixed-income areas is relatively rare—only 5 percent of our respondents live in mixed-income neighborhoods at both waves 1 and 4, whereas 65 percent of our respondents do not live in mixed-income neighborhoods at either wave. The balance, nearly a third of the sample (30 percent), transitions into or out of mixed-income neighborhoods between 1995 and 2012, once again suggesting fluidity in exposure to mixed-income neighborhoods.8

It is important to note that in Table 2 we used the national distribution of the ICE to determine the quintile cut points. Based on the national distribution, our mixed-income category consists of neighborhoods with ICE scores between −0.08 and 0.06 in 1995 and −0.06 and 0.10 in 2012. To test whether the results are sensitive to this definition, we examined ICE cut points based on the weighted distribution of sample respondents by the neighborhoods they lived in at waves 1 and 4. In this more local specification that is dominated by Chicago and its suburbs, the mixed-income category of neighborhoods includes those neighborhoods with ICE scores between −0.17 and −0.04 in 1995 and −0.19 and 0.03 in 2012. However, this definition does not alter our main findings about exposure to mixed-income neighborhoods. By both the national distribution and sample-based definitions, 5 percent of respondents lived in mixed-income neighborhoods at both waves 1 and 4. While using the national distribution shows that 21 percent of respondents who start in mixed-income neighborhoods end up in mixed-income neighborhoods, the corresponding statistic using the sample-based distribution is 24 percent. The basic pattern of exposure to mixed-income neighborhoods that we report above is thus robust to different cut points of the ICE variable.

Although revealing, the aggregate transition matrix in Table 2 conceals potential heterogeneity in exposure to poverty, affluence, and mixed-income areas by the race and ethnicity of the study participants. We thus examined exposure to our mixed-income classification of neighborhoods across the 18 years separately for Latinos, non-Latino blacks, and non-Latino whites. To simplify the data when looking at race and ethnicity, we examined a two-category classification that collapses the ICE quintiles into a mixed-income category versus all else. The results show that almost a third (29 percent) of young-adult Latinos who lived in mixed-income neighborhoods at wave 1 remained in mixed-income neighborhoods at wave 4, compared with only 18 percent of blacks and 13 percent of whites living in mixed-income neighborhoods at wave 1. Among respondents who do not live in mixed-income neighborhoods at wave 1, Latinos also have the highest rate of living in mixed-income neighborhoods at wave 4: 23 percent, compared with 12 percent and 11 percent for blacks and whites, respectively. Exposure to mixed-income neighborhoods is lowest among blacks, 70 percent of whom did not live in mixed-income neighborhoods at either wave 1 or 4 (table not shown). The equivalent statistics for Latinos and whites are 56 and 66 percent. Based on these results, Latino-Americans, at least in Chicago, are much more exposed to mixed-income neighborhoods.9

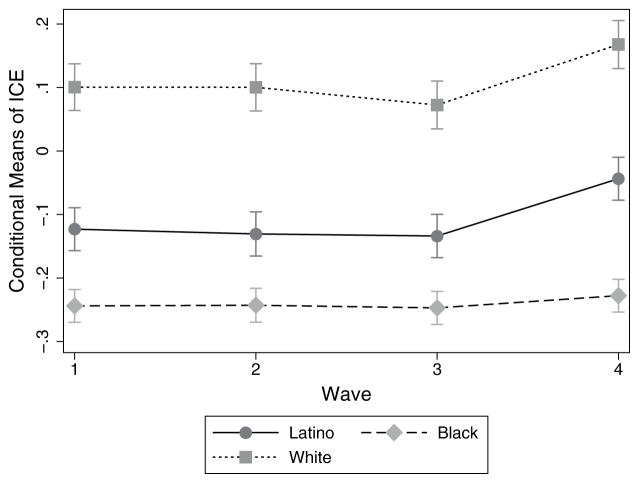

Another way to look at race differences is to examine the average trajectories of each group across the four waves of the MIP-Chicago study. Figure 3 presents the weighted trajectory results for ICE by race/ethnicity, with 95 percent confidence intervals shown for each group. In estimating these trajectories, we adjust for age cohort, homeowner status at wave 1, and parental immigrant status. As seen in Figure 3, the conditional mean differences among race/ethnic groups are quite stark at each wave of the study. Whites are much more likely to be exposed to higher values of concentrated affluence, and blacks to concentrated poverty (values of ICE below −.20). Latinos are again in the middle, with the final neighborhood attainment at nearly the middle (or .00) of the ICE distribution.

FIGURE 3.

Chicago ICE Trajectories of Young-Adult Sample by Race/Ethnicity, Adjusting for Baseline Homeowner Status, Immigrant Generation, and Age (95 Percent CI)

What is not yet clear is whether the consistent difference in experience we have observed so far among Latinos is a result of initial differences in socioeconomic status or different trajectories of residential mobility over time. In addition, we have not yet explored direct models of change in mixed-income exposure that simultaneously take into account demographic, socioeconomic, and residential mobility status. It is to these issues we now turn.

Who transitions to a mixed middle-income neighborhood?

Table 3 displays a series of models that predict whether our sample of young adults lives in a mixed-income neighborhood in 2012, controlling for baseline residence type in 1995. We are thus estimating a change model—that is, a model of who is most likely to transition into mixed-income residence over the course of the study. We begin with a logistic regression model that uses race, age, and residence in a mixed-income neighborhood at wave 1 to predict residence in a mixed-income neighborhood at wave 4. The results in model 1 show that living in a mixed-income neighborhood at wave 1 is positively related to living in a mixed-income neighborhood at wave 4 (model 1, OR = 1.40), but the coefficient is not significant at conventional levels. Controlling for age and residence in mixed-income neighborhood at wave 1, however, Latinos are substantially (2.7 times) more likely than whites to live in a mixed-income neighborhood at wave 4. Blacks are no more likely than whites to live in a mixed-income neighborhood at wave 4, and being in age cohort 12 compared with cohort 9 is only marginally associated with mixed-income neighborhood residence at wave 4.

TABLE 3.

Logistic Models Predicting Mixed Middle-Income Status at Wave 4

| Predictors | Models

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Mixed-income, wave 1 | 1.402 [0.797, 2.469] | 1.381 [0.782, 2.439] | 1.376 [0.700, 2.704] | 2.471 [0.757, 8.069] | 1.317 [0.733, 2.364] | 1.182 [0.642, 2.174] |

| Latino | 2.694** [1.314, 5.523] | 2.851** [1.422, 5.719] | 3.187** [1.378, 7.372] | 1.845 [0.417, 8.159] | 2.927** [1.380, 6.209] | 3.413** [1.545, 7.541] |

| Black | 1.165 [0.532, 2.548] | 1.147 [0.474, 2.774] | 0.889 [0.317, 2.497] | 0.652 [0.0809, 5.260] | 1.142 [0.455, 2.866] | 1.227 [0.479, 3.146] |

| Cohort 12 | 1.807+ [0.984, 3.318] | 1.760+ [0.956, 3.239] | 1.384 [0.692, 2.770] | 0.820 [0.305, 2.201] | 1.706+ [0.929, 3.133] | 1.773+ [0.953, 3.298] |

| Cohort 15 | 0.922 [0.478, 1.779] | 0.914 [0.472, 1.769] | 0.728 [0.338, 1.565] | 0.798 [0.286, 2.225] | 0.881 [0.454, 1.709] | 0.898 [0.446, 1.809] |

| Parent 1st generation | 0.920 [0.415, 2.037] | 0.718 [0.270, 1.911] | 2.143 [0.412, 11.15] | 0.922 [0.403, 2.108] | 0.870 [0.374, 2.020] | |

| Parent 2nd generation | 0.903 [0.327, 2.489] | 0.674 [0.215, 2.112] | 0.703 [0.114, 4.327] | 0.911 [0.333, 2.490] | 0.945 [0.357, 2.502] | |

| Homeowner, wave 1 | 1.253 [0.662, 2.373] | 1.263 [0.696, 2.295] | 1.313 [0.639, 2.698] | |||

| Public housing, wave 2 | 0.332 [0.0695, 1.589] | 0.302 [0.0462, 1.969] | ||||

| Moved in Chicago | 0.769 [0.434, 1.364] | |||||

| Moved outside of Chicago | 0.383* [0.160, 0.916] | |||||

| Parent education | 1.042 [0.766, 1.418] | |||||

| Household income: | ||||||

| $10,000–$19,999 | 0.547 [0.174, 1.724] | |||||

| $20,000–$29,999 | 1.852 [0.696, 4.929] | |||||

| $30,000–$39,999 | 1.290 [0.426, 3.906] | |||||

| $40,000–$49,999 | 1.103 [0.270, 4.515] | |||||

| > $50,000 | 1.273 [0.397, 4.080] | |||||

| N | 645 | 638 | 498 | 277 | 627 | 602 |

NOTE: Exponentiated coefficients; 95 percent confidence intervals in brackets.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Model 2 adds immigrant generation of the respondent’s parents to the model, capturing the immigrant context of the household in which the respondent was an adolescent. Compared with respondents with third-generation parents and controlling for race, age, and residence in a mixed-income neighborhood at wave 1, respondents with first- and second-generation parents are no more or less likely to live in a mixed-income neighborhood at wave 4. Adding immigrant generation to the model also does not change the main result from model 1: Latinos compared to whites are significantly more likely to live in a mixed-income neighborhood at wave 4, but controlling for generational status actually increases the odds ratio for Latinos to 2.8.

In model 3, we add indicators of parental home ownership at wave 1 and whether the respondent lived in public housing at wave 2 (circa 1997). Neither growing up in a house that was owned nor living in public housing significantly predicts residence in a mixed-income neighborhood at wave 4, controlling for living in a mixed-income neighborhood at wave 1, race, age, and parent immigrant generation. The odds ratio for being Latino compared with being white remains substantial (3.2) after accounting for public housing and homeowner-ship, while residence in a mixed-income neighborhood at wave 1 continues to be insignificant.

Model 4 is restricted to respondents who at wave 1 lived in homes that were rented. Although this specification reduces our sample size considerably, the model is justified because public housing residents were by definition not owners. In this restricted model, public housing is still not significantly associated with ending up in a mixed-income neighborhood at wave 4.

We next created indicators of neighborhood mobility status in the first three waves of the PHDCN: stayers, or those who did not move out of their baseline neighborhood over the first three waves (approximately seven years); movers within Chicago in the same period; and movers outside of the city proper again over the same period. Approximately 60 percent of the adolescent sample stayed in their family neighborhood as they transitioned to young adulthood, just under a third moved between neighborhoods but stayed within Chicago, and 11 percent moved out of the city. When we add the two indicator variables for moving within Chicago and out of Chicago (with the reference category being stayers) to model 5 in Table 3, we see that mobility status out of the city is associated with 62 percent lower odds of living in a mixed-income neighborhood compared with stayers; moves within the city are not significantly associated with mixed-income destinations. It appears that moving out of Chicago—mostly to the suburbs, but including regions around the country—is associated with increased odds of living in concentrated affluence and reduced odds of living in a mixed-income neighborhood.

The last model in Table 3 takes into account the relationship between family socioeconomic status during adolescence and residence in a mixed-income neighborhood at wave 4. To estimate this relationship, we include parental education and a series of dichotomous indicators for five categories of family income (with the reference group as those making less than $10,000 a year). Controlling for mixed-income neighborhood at wave 1, race, age, parent immigrant generation, and both homeownership and income status at wave 1, model 6 shows that none of the income indicators are significant.10 Nor does parental education predict residence in a mixed-income neighborhood at wave 4. Including the socioeconomic status of the family of origin, therefore, does not alter our consistent findings that Latinos are three to four times more likely to live in a mixed-income neighborhood than are whites.

One question remains. Because it is known that Latinos are disproportionately likely to live in neighborhoods with a greater Latino composition, do our findings then reflect a contextual compositional effect? For example, are Latinos simply more attracted to Latino areas? Building from the full specification in model 6, we reestimated our results controlling first for percent Latino at baseline (1995) and then in the destination neighborhood (ACS 2008–12). In neither case was percent Latino significant, but the individual-level odds ratios for Latinos compared with whites remained large and significant (2.96 and 3.4, respectively). In addition, we compared Latino composition by income quintiles for the United States and Chicago. In both cases, the percentage Latino is actually higher or the same in the first two quintiles. In fact, for the United States as a whole, percent Latino is twice as high in the bottom quintile compared with the mixed middle income. Like socioeconomic status, contextual ethnic composition thus does not explain the strong pattern of Latino transitions to mixed middle-income neighborhoods.

Conclusion

Increases in income segregation have generated considerable debate, especially the separation of the very rich from everyone else. But our analysis shows that separation at the top is expressed in stark spatial terms and that this has been the case for some time. Indeed, about 75 percent of all neighborhoods in the United States in the highest quintile of income in 1990 were still there almost two decades later. The concentration of poverty is also very persistent, with more than 70 percent of poor neighborhoods remaining poor over time; for the Chicago area, two-thirds of both poor and affluent areas retained their position. Mixed-income neighborhoods that are naturally occurring are comparatively more unstable; there appears to be more churning or turnover in the middle of the neighborhood income distribution rather than the rich and poor neighborhoods changing places.

How do individuals fare against this strong pattern of structural inequality? Surprisingly, much less is known about exposure to neighborhood income mixing across the life course. To correct this gap, we examined 671 adolescents in Chicago who were followed over an 18-year span as they transitioned to young adulthood. The results show that the concentration of income extremes is persistent in the lives of individuals almost as much as in neighborhoods. Exposure to mixed middle-income neighborhoods is more infrequent and unstable.

The persistence of concentrated income extremes suggests that policies seeking to promote mixed-income neighborhoods face greater odds than commonly thought. Yet one pattern deserves consideration in thinking about the stability of mixed-income areas. When we considered characteristics of the individuals in our sample, Latino-Americans were much more likely than African Americans or whites to be exposed to mixed middle-income neighborhoods in the first place and to transition into them over time, adjusting for immigrant status, education, income, and residential mobility. Interestingly, this pattern is not explained by Latinos simply moving from or to neighborhoods with more Latinos.

Although our results call for more probing, the influx of immigration from Latin American countries may be not only creating a more diverse society but also inducing more income-mixing in the middle of the income distribution, perhaps offsetting what would otherwise be larger losses in the middle class as income inequality and the spatial separation of the poor and affluent increase. Immigrant and ethnic diversity thus need to be central to any debate over income mixing; the “black and white” frame that has dominated the urban sociology literature for decades will not suffice to capture the neighborhood context of income mixing now.

Acknowledgments

NOTE: This article was supported in part by Grant #95200 from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and a grant from the Hymen Milgrom Supporting Organization to the University of Chicago.

Footnotes

For a review of trends and an analysis of the increasing separation of poverty and affluence at the neighborhood level, see Reardon and Bischoff (2011).

Mixed-income housing is not without controversy. For a discussion of conflict in New York City’s efforts, see http://nyti.ms/1pDg4G5.

The mobility of the sample reached well beyond the neighborhood clusters (themselves made up of census tracts) of the original PHDCN sampling design. We thus use census tracts to capture the income status of destination neighborhoods, assigning 2000 census tract boundaries for waves 1–3 and 2010 boundaries for wave 4. This strategy comports with past research and reflects the most accurate measure of the neighborhoods in which the participants were living at the time of each wave of data collection. For the neighborhood-level analyses we use 2000 boundaries to track neighborhood change from 1990 to 2009.

The entropy index is another candidate, but it gives the highest value to neighborhoods that are 50 percent poor and 50 percent affluent, which is a very rare context. Of census tracts in Chicago with more than 40 percent affluent, for example, none have a percentage poor greater than 40 and just a handful have greater than 25. The middle of the ICE distribution captures 50/50 splits but also the more realistic splits closer to 20 or 30 percent poor and 20 to 30 percent affluent.

We also decomposed the ICE into variability between census tracts and over time for all neighborhoods in the United States for the independent census years 1990, 2000, and 2005–9. The results revealed that 88 percent of variation is between neighborhoods. The same general pattern holds in Chicago. Thus the variability in concentrated income extremes is predominantly between neighborhoods rather than over time, which means that, consistent with Figure 2, relatively few neighborhoods are switching positions in the income distribution.

To maximize the temporal match to the main MIP follow-up interview year in 2012, we use the ACS, 2008–12. Because the Chicago area is similar to the national distribution of income, the results are similar if we use the local (county-level) quintile distribution.

The sampling weight is designed to adjust for the original stratification of the PHDCN by neighborhood SES and racial composition, along with the age-cohort selection and a post-stratification of population weights to census estimates of the age, gender, and race/ethnicity distribution of children in the City of Chicago in 1995. The attrition weight is defined as the inverse of the probability of being interviewed at wave 4 conditional on being in the study at wave 3. To model the probability of attrition at wave 4, missing data from waves 1 through 3 were first multiply imputed using chained regression equations. Attrition weights were then calculated by estimating a logit model for the probability of attrition at wave 4, based on individual- and household-level measures (e.g., socioeconomic status and family structure) as well as neighborhood-level measures of demographic composition and social processes (such as collective efficacy and perceived violence). The inverse of each subject’s probability of response was then calculated and standardized by the mean to yield the final attrition weights. The stratification and attrition weights were multiplied to produce the final weight. We examined results separately using the baseline stratification weights and attrition-based weights, but the patterns were very similar; therefore, we present data based on the final weights.

We also examined the Herfindahl index of income diversity defined earlier. Consistent with our typology, income diversity is significantly higher in the mixed-income category (.75) than the non-mixed-income category (.68) in our wave 4 sample (t-ratio of difference = −9.81; p < .01).

We also examined the immigrant status of parents among Latinos; there was a similar level of consistent exposure to mixed-income neighborhoods when comparing the first generation to the second and third generations. There is a somewhat bigger difference in mixed-income at wave 4 conditional on wave 1, with first-generation immigrants having a higher prevalence of living in mixed income at wave 4 conditional on wave 1.

We also examined an alternative model where we substituted welfare (TANF) receipt by the parent at wave 1 for income. But like income, welfare did not predict living in a mixed middle-income neighborhood. In addition, although most covariates in Table 3 have only modest levels of missing data, we reestimated all models using multiply imputed data to assess the robustness of results. We obtained substantively similar results.

Contributor Information

ROBERT J. SAMPSON, Henry Ford II Professor of the Social Sciences at Harvard University

ROBERT D. MARE, Distinguished professor of sociology at UCLA

KRISTIN L. PERKINS, PhD candidate in sociology and social policy at Harvard University

References

- Bruch Elizabeth E, Mare Robert D. Neighborhood choice and neighborhood change. American Journal of Sociology. 2006;112:667–709. [Google Scholar]

- Cisneros Henry G, Engdahl Lora., editors. From despair to hope: HOPE VI and the new promise of public housing in America’s cities. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen Ingrid Gould. Sharing America’s neighborhoods: The prospects for stable racial integration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang Jackelyn, Sampson Robert J. Divergent pathways of gentrification: Racial inequality and the social order of renewal in Chicago neighborhoods. American Sociological Review. 2014;79:726–51. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph Mark L, Chaskin Robert J. Mixed-income developments and low rates of return: Insights from relocated public housing residents in Chicago. Housing Policy Debate. 2012;22(3):377–405. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph Mark L, Chaskin Robert J, Webber Henry S. The theoretical basis for addressing poverty through mixed income development. Urban Affairs Review. 2007;42:369–409. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S. The prodigal paradigm returns: Ecology comes back to sociology. In: Booth Alan, Crouter Ann., editors. Does it take a village? Community effects on children, adolescents, and families. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001. pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Moore Natalie. CHA slows down on mixed-income housing. 2013 Available from http://www.wbez.org.

- Piketty Thomas. Capital in the twenty-first century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon Sean F, Bischoff Kendra. Income inequality and income segregation. American Journal of Sociology. 2011;116:1092–1153. doi: 10.1086/657114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson Robert J. Great American city: Chicago and the enduring neighborhood effect. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson Robert J, Sharkey Patrick. Neighborhood selection and the social reproduction of concentrated racial inequality. Demography. 2008;45:1–29. doi: 10.1353/dem.2008.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson William Julius. The truly disadvantaged: The inner city, the underclass, and public policy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]