Abstract

Secondary lymphoid stroma performs far more functions than simple structural support for lymphoid tissues, providing a host of soluble and membrane-bound cues to trafficking leukocytes during inflammation and homeostasis. More recently it has become clear that stromal cells can manipulate T cell responses, either through direct antigen-mediated stimulation of T cells or more indirectly through the retention and management of antigen after viral infection or vaccination. In light of recent data, this review provides an overview of stromal cell subsets and functions during the progression of an adaptive immune response with particular emphasis on antigen capture and retention by follicular dendritic cells (FDC) as well as the recently described “antigen archiving” function of lymphatic endothelial cells (LEC). Given its impact on the maintenance of protective immune memory, we conclude by discussing the most pressing questions pertaining to LEC antigen capture, archiving and exchange with hematopoetically derived antigen-presenting cells.

Historically, immunologists have been largely focused on studying the hematopoietically-derived cells that are involved in the direct recognition and control of pathogen specific immune responses. Consequently, the participation of non hematopoietically-derived stromal cells in the initiation and maintenance of immunity has been under-appreciated, though in recent years more intensively studied. While structural support of the lymphoid tissue during homeostasis and inflammation is a primary function of the stroma, various stromal cells are also recognized as having an active role in the immune response through their interactions with hematopoietic cells. In order to accommodate the influx of neutrophils, macrophages, dendritic cells and lymphocytes recruited during an immune response, stromal cells are required to initiate expansion of the lymph node through its loss of contractility, to regulate the movement of trafficking immune cells into the lymphoid structure, and ultimately to sense the resolution of the response and return to homeostasis. In this context, some novel functions for stromal cell subsets have recently been documented. We recently showed that during their expansion to meet the spacial demands of the swelling lymph node, lymphatic endothelial cells (LEC) actively capture and retain antigens. This effectively “archives” antigen in the host for periods of time well beyond the rise and fall of the adaptive immune response to said antigens. Until this report, the persistence of antigens within secondary lymphoid structures was largely, if not exclusively, believed to be a function of follicular dendritic cells (FDC), well known to capture and maintain antigen-antibody complexes for months/years after initial antigen encounter. These LEC-archived antigens influence the phenotype and function of circulating antigen-specific memory CD8+ T cells, similar to what has been documented in response to viral antigens that persist well after the resolution of infection (2-8). This review will focus on summarizing the various stomal cell subsets with an emphasis on LECs and FDCs, the role of LECs during lymph node swelling and contraction, and what roles these stromal cells play in shaping the immune response.

Stromal cell subsets

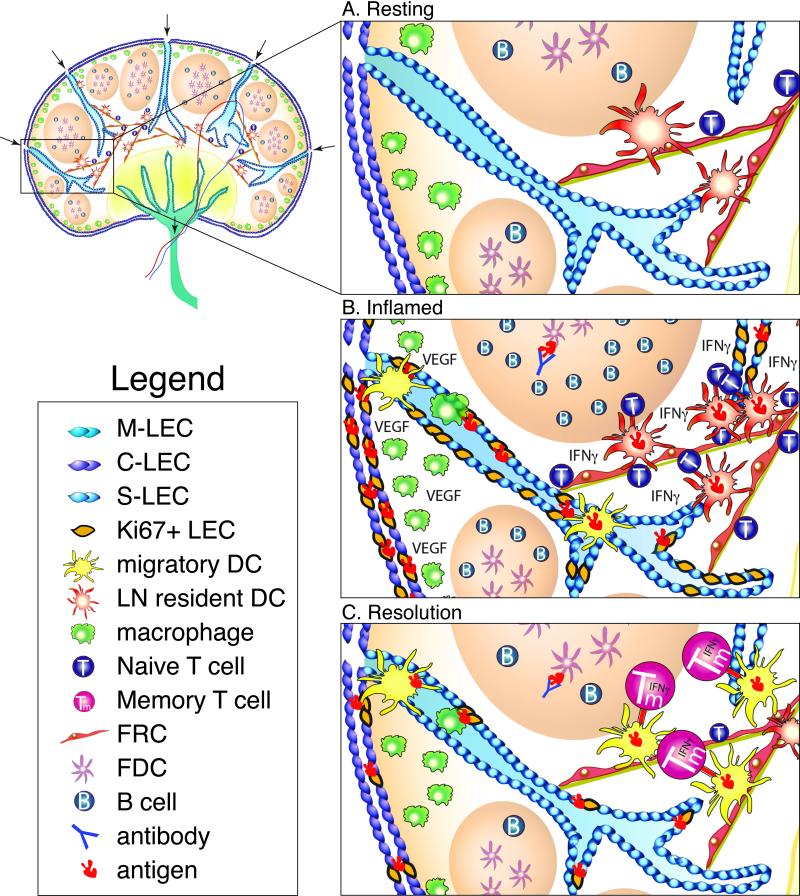

The secondary lymphoid tissue is a highly ordered and structured tissue, segregating hematopoietic (CD45+) and stromal cells (CD45−) into specific compartments and domains. The five major stromal cell subsets, Follicular Dendritic cells (FDC), lymphatic endothelial cells (LEC), Fibroblastic reticular cells (FRC), Marginal reticular cells (MRC) and blood endothelial cells (BEC) can be identified by both their location in the lymph node as well as their expression of podoplanin (PDPN), CD31, complement receptor 1/2 (CR1/2-CD21/35) and MadCAM. Both LEC and BEC express CD31 but BEC are the only cell to not express PDPN (9). MRCs and FRCs express PDPN but are negative for both CD31 and CD21/35 (9). LECs express both PDPN and CD31 but not CD21/35. FDCs can be delineated from FRCs and MRCs by their expression of CD21/35, FDC-M1, FDC-M2, and their physical location within the B cell follicle (10-12). MRCs can be delineated from FRC not only by their expression of MadCAM, but also by their localization to the subcapsular regions of the node (13). It is thought that MRC are related to lymphoid tissue organizer cells (LTo) (13) and that MRC and/or FRC can initiate the regeneration of stroma in collaboration with lymphoid tissue inducer cells (14). FRC are found throughout the T cell zone and around the B cell follicle with a few FRCs present within the B cell follicle (15). FRCs support the migration and response of DCs (16), T cells (16, 17) and B cells (15). The remaining two stromal cell types, FDCs and LECs, will be discussed in more depth due to their capacity to capture and maintain antigens for extended periods of time (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Lymph node architecture and the response to inflammation.

A. A lymph node at rest. Lymph nodes are lined with subcapsular LECs (S-LEC purple), which branch into the T cell zone as cortical LECs (C-LEC blue), and can intersect with medullary LECs (M-LECs green) in the medulla. Lymph flows freely from the afferent lymphatics, through LEC-lined channels, and out through the efferent lymphatics. Within the lymph node, the B cell follicle contains FDCs and B cells. Macrophages line the subcapsular sinus, poised to initiate inflammation upon recognition of foreign invaders. Dendritic cells migrate along FRCs layered on top of an extracellular matrix, interacting with PDPN on FRCs via expression of CLEC2. T cells scan DCs within the T cell zone as they migrate along FRC conduits. B. Inflamed lymph node. Following infection or inflammation, lymph node swelling occurs as a result of macrophage, monocyte, and neutrophil activation via TLRs. Activation of these macrophages, FRCs, and DCs induces increased expression of VEGF, which along with IL-7 production (not shown) induces LEC proliferation (lymphangiogenesis) as indicated by Ki67 expression. Additionally, migratory DCs, such as CD103+ DCs, and immature monocytes migrate from the tissues into the lymph node where they can pick up antigen and present to T cells within the T cell zone. During this inflammatory process antigens are archived on proliferating LECs in response to the robust immune response. As antigen specific T cells expand and are activated, they produce IFNγ, eventually contributing to LEC attrition subsequent to the resolution of infection. Within the B cell follicle, germinal center formation occurs and antigen specific B cells expand in number. Small amounts of antigen-antibody complexes are captured by FDCs where they reside for future B cell acquisition. C. Resolution of inflammation and return to homeostasis. Following the resolution of the immune response, LEC numbers contract as shown by decreased Ki67+ LECs, possibly mediated by T cell production of IFN γ and/or a decrease in VEGF expression by monocytes/macrophages. Migratory DCs, possibly CD103+ DCs, and macrophages enter the lymph node during the process of contraction to pick up any apoptotic cells or cellular debris. Antigen acquisition by migratory DCs and macrophages pick up apoptotic LECs containing antigen, a possibly mechanism of antigen exchange between LECs and APCs. These migratory DCs then present antigen to memory T cells (Tm), resulting in increased effector function and protection against secondary infection.

FDCs

Antigen uptake by FDCs has been well described, having been originally discovered in the 1960s. The capture and maintenance of antigen by the FDCs relies on its use of CD21, complement receptor 2 (CR2), to bind to antigen/antibody complexes formed during the course of an immune response. With their localization in the light zone of the B cell follicle, FDC-mediated presentation of captured antigen to antigen-specific B cells in the follicle is necessary for the formation of the germinal center reaction, culminating in the production of high affinity antibodies (11, 18-20). Though CR2 and C3 have long been known to be critical for the function of FDCs, the complex process by which antigen is eventually acquired by the FDC has only relatively recently been understood ((11, 21, 22) and reviewed in (12)). Subcapsular sinus macrophages initially capture C3d-coated immune complexes via Fc receptors and CR3 (23). The macrophages then transport antigen to naïve B cells expressing CR2. Crystallization studies of C3d bound to CR2 and CR3 implicate different binding sites within the C3d structure (24-26) suggesting both macrophages and B cells are able to bind C3d at the same time and that antigen hand-off from macrophages to B cells is possible. Naïve B cells then transport the antigen to the B cell follicle where antigen is transferred to FDCs (11, 21, 22). FDC acquisition of antigen from the B cells may then occur due to their higher CR2 expression, though this is still not well understood (12). Though longer times have been proposed, the duration of antigen retention on FDCs has been estimated to be on the order of months (12, 20, 27-29). Whatever the duration of antigen maintenance by FDCs, captured, opsonized immune complexes are continuously recycled through non-degrading endosomal compartments, allowing B cells to acquire antigen-antibody complexes and be stimulated through antigen specific BCRs. These longer time points of antigen maintenance are thought to contribute to the turnover of memory B cells as well as their conversion into antibody producing plasma cells, thus maintaining the frequency of antigen specific memory B cell precursors as well as the level of antigen specific serum Ig (11, 18, 19, 30, 31).

FDCs have also been implicated in the maintenance of antigen that is eventually used for the stimulation of memory CD4 and CD8 T cells. Some of these studies show that antigen-antibody complexes, localizing to B cell follicular regions, can eventually stimulate circulating naïve and memory T cells (32, 33). Other studies examining the persistence of viral antigens within secondary lymph nodes more indirectly implicate FDCs in the maintenance of persisting viral antigens in the host (3). Regardless, FDCs have either been assumed or demonstrated to be the only stromal cell type involved in the capture and maintenance of antigen for any period of time extending past the rise and fall of the primary adaptive response (Figure 1b).

LECs

Besides being the cell type lining all lymphatic vessels, three distinct groups of LECs reside within the lymph node, historically designated by their location. Subcapsular sinus LECs (S-LECs) line the outside of the lymph node and form a thin sinus where they come in contact with Subcapuslar sinus (SCS) macrophages and other immune cells traversing this space (Figure 1). Cortical LECs (C-LECs) form the vessels that branch into the T cell zone between B cell follicles and can intersect both S-LECs and the medullary LECs (M-LECs). The M-LECs are found at LN exit within the medulla of the LN (34-36) (Figure 1a). Besides their differences in localization, these different subsets were recently delineated by their expression of PD-L1, ICAM-1, MAdCAM-1, and LTβ(37). The canonical function of LECs is managing the flow of lymph as it enters the node through the SCS proximal to the cortical region (afferent lymph) and exits the node through cortical and medullary sinuses (efferent lymph) (Figure 1 arrows). However, the lymphatic endothelium is also responsible for producing chemokines such as CCL21 (38), CXCL12 (39), and CCL1 (40) to direct DCs, T cells, and B cells that express CCR7 (41, 42), CXCR4, and CCR8, respectively, into the lymph node (38, 39, 43), and SCS (40). Furthermore, lymphatic endothelial cells are the major source of S1P which facilitates T cell egress from the LN during an immune response (44). Thus, LECs help regulate the migration of immune cells originating in the tissues that traffic into the draining node during periods of homeostasis and inflammation (Figure 1b). During periods of homeostasis, this largely involves the migration of memory T cells and tissue-resident immature dendritic cells through the afferent lymph and the emigration of all lymphocytes out through the efferent lymph. However, under inflammatory conditions such as that present during viral infection, LECs express the chemokines required to draw activated APCs and lymphocytes from the tissues (45-47) and into the node for the initiation of adaptive immunity (Figure 1b). Additionally, the dramatic influx of inflammatory cells and exponential expansion of pathogen specific T and B cells require the LECs to proliferate to allow for LN swelling (1).

More recently however, LECs have been shown to do more than serve as the highway for lymph and lymphocyte trafficking. Data from a number of groups has revealed that LECs are potent presenters of self-antigens and participate in the maintenance of peripheral T cell tolerance (37, 48-53). This LEC function borne out in a tumor setting results in LECs being coopted by the tumor to prevent the generation of tumor specific immunity (54, 55). In addition, the conditions present during the early stages of an inflammatory response appear to be competent to engage LECs in the initial presentation of antigens via MHC class I and class II molecules (49). Along with these reports establishing that LECs can participate more directly in the adaptive immune response, we found an unexpected, but central, role for LECs in maintaining protective CD8+ T cell immunity through their “archiving” of captured of antigens.

Antigen archiving by LEC

Though counter examples do exist, studies from numerous groups, using a variety of viral infections (influenza, VSV, vaccinia) document the persistence of virally associated antigens within the secondary lymphoid tissue well after the clearance of replicating virus (1-5, 7, 57, 58). A good example is influenza where infectious particles are cleared by 14 days after initial infection but flu related antigens are detectable in the host for more than a month afterward. In the case of flu infection, both CD4 and CD8+ T cells can respond to antigen maintained within the secondary lymphoid tissue, the persistence of which was previously localized to an undetermined radio-resistant stromal cell (3). Similarly, our studies found that antigen persisted for 30+ days after either vaccinia virus challenge or subunit vaccination (1). Using B cell deficient and CR2 deficient hosts (59, 60), we were surprised to find no role for FDCs in this antigen persistence, implicating the participation of a different cell type. Through the use of fluorescent antigen, we found that LECs were responsible for acquiring and maintaining antigen for weeks after vaccination. The larger conclusions from these experiments were that i) LEC expansion/proliferation correlated with antigen capture by the LECs, and ii) induction of LEC proliferation required the combined action of an inflammatory stimulus (eg. innate receptor stimulation such as a TLR) in conjunction with the expansion of T cells within the lymphoid tissue. Given these inflammatory requirements, we coined the term “antigen archiving” to describe this process of LEC antigen capture and maintenance as it resembled the collection and storage of information that could prove to be useful over time. Bone marrow chimera experiments using hosts (stroma) that either could or could not present the persisting antigen showed that LECs were incapable of presenting the archived antigen via MHC class I, depending instead on hematopoietically derived cells for this function (Figure 1c- DCs present archived antigen). This is in contrast to the functional capabilities of LECs during the early phases of inflammation where they appear to directly cross present exogenous antigens (49). Finally, and consistent with previous results in viral model systems, memory T cells circulating in hosts with archived antigen were better at effector functions and immune protection against infection than were memory T cells circulating in naïve hosts. Collectively our results described a new function for LECs in which they archive antigen for eventual presentation to CD8+ T cells by hematopoietic APCs, ultimately promoting protective cellular immunity. As usual, results such as these produce more questions than answers, chief among them being what are the signals controlling LEC proliferation that lead to antigen capture, by what molecular means are LECs capturing and archiving antigen, and how do LECs ultimately release antigen to hematopoietically derived APCs for presentation to circulating memory T cells.

The control of LEC proliferation

Following immunization or infection a number of processes occur that involve the lymph node stroma. First, any number of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) recognize the offending pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). These PAMPs are recognized by macrophages (Figure 1), neutrophils, dendritic cells, and stromal cells by PRRs expressed on these cells (61). Upon activation of the innate immune system an influx of neutrophils, migratory dendritic cells, monocytes, and macrophages occurs in the lymph node due to expression of a variety chemokines (Figure 1b). For example, expression of CCR7 by migratory DCs is upregulated following PRR engagement (45-47). The dendritic cell then migrates to the lymph node guided by its interaction with CCL21 produced by the afferent lymphatic vessels and FRCs within the node. Upon trafficking to the lymph node, migratory DCs migrate through LEC lined vessels and interact with FRCs. Recent work showed that C-type lectin receptor 2 (CLEC2) on migratory DCs binding to its ligand, podoplanin (PDPN) expressed on FRCs resulted in relaxation of contractility and a loss of tissue stiffness, ultimately allowing for swelling of the lymph node and proliferation of the FRCs (Figure 1) (62, 63). This effect could be recapitulated through use of an αPDPN antibody, relaxing LN stiffness and increased FRC numbers (62, 63). During the inflammatory process not only does the lymph node relax, but the lymphatic vessel grows and the lymph node increases in size at least in part due to LEC division (Figure 1b). Lymphangiogenesis (the process of lymphatic vessel growth and differentiation (64)) is also thought to occur through the Vascular Endothelial Growth Factors (VEGF), namely VEGF A, C, and D (65-67) which are secreted by FRCs, macrophages, and dendritic cells at the sight of inflammation (Figure 1b-VEGF). Furthermore, LECs are major producers of IL-7 (68), which signals in an autocrine fashion through IL-7 receptor alpha (CD127) (68, 69), resulting in lymph node reconstruction and remodeling following infection (69). A reasonable model holds that stimulation of macrophages and dendritic cells by an innate activator, such as a TLR agonist or infection, leads to FRCs/macrophage secretion of VEGF, and in turn IL-7 by LECs, resulting in lymph node remodeling (69). In conjunction with engagement of PDPN by migrating leukocytes causing FRC relaxation, lymphangiogenesis is induced resulting an increase in LN size (Figure 1b). Consistent with this, lymphangiogensis is compromised in PDPN−/− (63), or IL7R−/− (64) mice, or through the use of blocking antibodies against VEGF A and C (60, 61).

It is presently unclear what aspect(s) of this proliferative process render the LEC capable of antigen acquisition. Whatever molecules may be involved in antigen capture (see below), our data indicate that the expression of this putative antigen-binding molecule/receptor would only be induced in response to inflammatory cues. Alternatively, our putative antigen-binding molecule/receptor may be stored in an intracellular compartment and only exocytosed to the cell surface in response to inflammation. This would be analogous to the effect of inflammation on the exocytosis of Weibel-Palade bodies found in BECs (70). Considering the developmental and transcriptional similarities between BECs and LECs (71), both transcriptional and non-transcritional based mechanisms should be explored to understand the connection between LEC proliferation and antigen capture.

LEC antigen capture

Though much is known regarding FDC management of antigen-antibody complexes (11, 12, 21, 22, 29, 32, 72, 73), the molecular means by which LECs capture and hold antigen for such long periods of time is currently unknown and thus any discussion of this process is, by definition, highly speculative. The necessity of lectin-glycan interactions in regulating viral recognition, immune surveillance, control, and capture has been documented by others (74). As the process of antigen archiving has likely evolved as a response of the host to viral infections, it is possible that the same lectins involved in viral recognition/management may participate in the capture of glycosylated antigens on the LEC surface. Alternatively, and analogous to FDC antigen management, a CR2-independent, complement-dependent mechanism may facilitate LEC antigen capture and retention. Indeed, microarray data acquired by the Immunological Genome Project Consortium for Stromal cell types (75) may be consistent with this. Comparing the expression profile of LECs before and after inflammation + T cell activation (24 hours after OT1 transfer and immunization with Ova+LPS), Itgb2 or Cr3 (CD11b/CD18) was unregulated more than 3 fold when compared to resting LECs. Given its almost ubiquitous presence during inflammatory processes, it is reasonable to suspect any of the receptors involved in complement activation and management. Furthermore, Cr3 is able to mediate phagocytosis of iC3b-coated apoptotic cells and aid in bacterial persistence without fusing to lysosomes (76), thus delaying the proteolytic breakdown of any associated proteins. This fits well with our observation that LEC captured antigen is poorly processed by the LEC (1), and would again be analogous to CR2 mediated endocytosis and recycling of unprocessed antigen-antibody complexes on FDCs (11). Again, these predictions are merely speculative, but serve as a good starting point for identifying the key players in LEC antigen capture.

Antigen transfer from LECs to DCs

Though some data suggest that LECs can present exogenous antigen to CD8+ T cells (cross presentation) early after the initiation of an immune response (49), our data clearly show that LEC-archived antigen must be exchanged with DCs to be presented to T cells. Cortical sinus LECs are in close contact with DCs travelling through the LN and to the T cell zone, and could act as antigenic gate keepers of the lymphatic flow (50). Antigen transfer from SCS macrophages to B cells, B cells to FDCs, and even back again to B cells has been documented (11, 20-22). In regards to more conventional DCs, others have reported antigen transfer from macrophages to CD103+ DCs (77), between DC subsets (78), and more recently between DCs, LECs and macrophages (1, 48, 79). Despite these numerous reports, we currently lack a clear picture of how this transfer of antigen occurs. Various versions of antigen transfer have been documented, from the use of gap junctions (77) in the gut to the export of antigen in peptide form by trogocytosis (80) or secreted extracellular vesicles (81), but none have yet been explored in the context of lymphoid stroma.

Given the role of specific DC subsets in the capture and processing of antigen derived from apoptotic cells, it is tempting to speculate that antigen exchange between LECs and DCs may be the result of the attrition of LECs during LN contraction. During lymph node contraction, LECs must go through apoptosis in order for the LN to shrink to normal size (67, 82). A recent manuscript elegantly demonstrated that IFN γ produced by antigen specific T cells negatively regulates lymphangiogenesis, eventually causing LN regression (82)(Figure 1b). During the LEC apoptosis that accompanies lymph node contraction, the apoptotic, antigen bearing LECs may be removed by tissue derived CD103+ DCs, a well described migratory DC subset responsible for uptake of apoptotic cells and cross-presentation of related antigens (83, 84) (Figure 1c). Indeed, CD103+ dendritic cells from the lung upregulate phosphatidyl serine receptors such as CD36 and Clec9a capable of acquiring apoptotic cells/cell membrane (84). However, both CD11b LN-resident DCs and SCS macrophages are also present in close proximity to the LEC with archived antigen and may well also serve as an intermediary in antigen exchange. Indeed, monocytes/macrophages are incredibly useful at mopping up cellular debris and can migrate into the LN even under non-inflammatory conditions (Figure 1c). Further, like CD103+ DCs, monocytes/macrophages express phagocytic receptors such as CD36, avb3 integrin and phosphatidyl serine receptors (85).

That said, a recent report showed antigen transfer from LECs to hematopoietically derived APCs, in this case for presentation via MHC class II, during steady state conditions (79). The fact that this transfer occurred in the absence of resolving inflammation may indicate that our “LEC attrition” model of antigen transfer is either incorrect or simply insufficient to explain all possible means by which antigen can be transferred between LECs and APCs. It is worth noting, however, that LEC turnover during steady state conditions has never been measured and may well be occurring at some rate. Indeed, if LEC apoptosis is a means by which antigen can be transferred to APCs, then the observation of antigen transfer in the steady state (79) could be evidence for LEC attrition in the absence of overt inflammation. Regardless, an “LEC attrition” model of antigen exchange is at least reasonable and testable contributor to the process of antigen transfer between LECs and APCs.

Concluding remarks

While mechanisms of LEC proliferation, antigen capture and archiving, and antigen exchange with hematopoietic cells are still largely in question, what is not in question is the beneficial impact that archived antigen has on the maintenance of protective immunity. Numerous studies established that stromal cell-mediated antigen persistence after viral infection positively influences the function and/or trafficking of the memory T cell pool, effectively promoting more rapid effector responses in the periphery and better control of secondary infectious challenges (3-5, 7, 86). Our data similarly show that LEC-archived antigen, while not necessary for memory CD8 T cell formation, clearly influences the quality of the memory T cell response. Specifically, in a system where all other variables are the same except LEC archived antigen, the difference in the functional readout of CD8 T cells is dramatic. Both the number and percentage of polyfunctional T cells (IFNg/IL2/TNFa) are significantly increased when antigen is retained on the LECs (1). Furthermore, the ability of these cells to protect against secondary infection is increased by ~3 logs when in the presence of archived antigen (1). Given this impact of persisting antigen on the function of protective memory, after either viral challenge or vaccination, exploring the mechanisms of antigen transfer and the boundaries with which antigen is held in the lymph node are of critical importance to understanding the broad impact of stromal cells in the immune response. In investigating these mechanisms, we will advance our understanding of the basic processes that occur following immunization and infection and design better ways of protecting against pathogens which require the activity of both hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cells of origin.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by NIH grants AI099863 and AI06612.

Footnotes

The authors confirm that they have no conflict of interests to declare.

References

- 1.Tamburini BA, Burchill MA, Kedl RM. Antigen capture and archiving by lymphatic endothelial cells following vaccination or viral infection. Nature communications. 2014;5:3989. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jelley-Gibbs DM, Brown DM, Dibble JP, Haynes L, Eaton SM, Swain SL. Unexpected prolonged presentation of influenza antigens promotes CD4 T cell memory generation. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2005;202(5):697–706. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim TS, Hufford MM, Sun J, Fu YX, Braciale TJ. Antigen persistence and the control of local T cell memory by migrant respiratory dendritic cells after acute virus infection. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2010;207(6):1161–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim TS, Sun J, Braciale TJ. T cell responses during influenza infection: getting and keeping control. Trends Immunol. 2011;32(5):225–31. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takamura S, Roberts AD, Jelley-Gibbs DM, Wittmer ST, Kohlmeier JE, Woodland DL. The route of priming influences the ability of respiratory virus-specific memory CD8+ T cells to be activated by residual antigen. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2010;207(6):1153–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turner DL, Cauley LS, Khanna KM, Lefrancois L. Persistent antigen presentation after acute vesicular stomatitis virus infection. J Virol. 2007;81(4):2039–46. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02167-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zammit DJ, Turner DL, Klonowski KD, Lefrancois L, Cauley LS. Residual antigen presentation after influenza virus infection affects CD8 T cell activation and migration. Immunity. 2006;24(4):439–49. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ely KH, Cookenham T, Roberts AD, Woodland DL. Memory T cell populations in the lung airways are maintained by continual recruitment. Journal of immunology. 2006;176(1):537–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Link A, Vogt TK, Favre S, Britschgi MR, Acha-Orbea H, Hinz B, Cyster JG, Luther SA. Fibroblastic reticular cells in lymph nodes regulate the homeostasis of naive T cells. Nature immunology. 2007;8(11):1255–65. doi: 10.1038/ni1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roozendaal R, Mebius RE. Stromal cell-immune cell interactions. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:23–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heesters BA, Chatterjee P, Kim YA, Gonzalez SF, Kuligowski MP, Kirchhausen T, Carroll MC. Endocytosis and recycling of immune complexes by follicular dendritic cells enhances B cell antigen binding and activation. Immunity. 2013;38(6):1164–75. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heesters BA, Myers RC, Carroll MC. Follicular dendritic cells: dynamic antigen libraries. Nature reviews Immunology. 2014;14(7):495–504. doi: 10.1038/nri3689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katakai T, Suto H, Sugai M, Gonda H, Togawa A, Suematsu S, Ebisuno Y, Katagiri K, Kinashi T, Shimizu A. Organizer-like reticular stromal cell layer common to adult secondary lymphoid organs. Journal of immunology. 2008;181(9):6189–200. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scandella E, Bolinger B, Lattmann E, Miller S, Favre S, Littman DR, Finke D, Luther SA, Junt T, Ludewig B. Restoration of lymphoid organ integrity through the interaction of lymphoid tissue-inducer cells with stroma of the T cell zone. Nature immunology. 2008;9(6):667–75. doi: 10.1038/ni.1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cremasco V, Woodruff MC, Onder L, Cupovic J, Nieves-Bonilla JM, Schildberg FA, Chang J, Cremasco F, Harvey CJ, Wucherpfennig K, et al. B cell homeostasis and follicle confines are governed by fibroblastic reticular cells. Nature immunology. 2014;15(10):973–81. doi: 10.1038/ni.2965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mueller SN, Germain RN. Stromal cell contributions to the homeostasis and functionality of the immune system. Nature reviews Immunology. 2009;9(9):618–29. doi: 10.1038/nri2588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown FD, Turley SJ. Fibroblastic reticular cells: organization and regulation of the T lymphocyte life cycle. Journal of immunology. 2015;194(4):1389–94. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qin D, Wu J, Carroll MC, Burton GF, Szakal AK, Tew JG. Evidence for an important interaction between a complement-derived CD21 ligand on follicular dendritic cells and CD21 on B cells in the initiation of IgG responses. Journal of immunology. 1998;161(9):4549–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, Cho B, Suzuki K, Xu Y, Green JA, An J, Cyster JG. Follicular dendritic cells help establish follicle identity and promote B cell retention in germinal centers. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2011;208(12):2497–510. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki K, Grigorova I, Phan TG, Kelly LM, Cyster JG. Visualizing B cell capture of cognate antigen from follicular dendritic cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2009;206(7):1485–93. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phan TG, Green JA, Gray EE, Xu Y, Cyster JG. Immune complex relay by subcapsular sinus macrophages and noncognate B cells drives antibody affinity maturation. Nature immunology. 2009;10(7):786–93. doi: 10.1038/ni.1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phan TG, Grigorova I, Okada T, Cyster JG. Subcapsular encounter and complement-dependent transport of immune complexes by lymph node B cells. Nature immunology. 2007;8(9):992–1000. doi: 10.1038/ni1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Junt T, Moseman EA, Iannacone M, Massberg S, Lang PA, Boes M, Fink K, Henrickson SE, Shayakhmetov DM, Di Paolo NC, et al. Subcapsular sinus macrophages in lymph nodes clear lymph-borne viruses and present them to antiviral B cells. Nature. 2007;450(7166):110–4. doi: 10.1038/nature06287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bajic G, Yatime L, Sim RB, Vorup-Jensen T, Andersen GR. Structural insight on the recognition of surface-bound opsonins by the integrin I domain of complement receptor 3. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(41):16426–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311261110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szakonyi G, Guthridge JM, Li D, Young K, Holers VM, Chen XS. Structure of complement receptor 2 in complex with its C3d ligand. Science. 2001;292(5522):1725–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1059118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van den Elsen JM, Isenman DE. A crystal structure of the complex between human complement receptor 2 and its ligand C3d. Science. 2011;332(6029):608–11. doi: 10.1126/science.1201954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tew JG, Mandel T, Burgess A, Hicks JD. The antigen binding dendritic cell of the lymphoid follicles: evidence indicating its role in the maintenance and regulation of serum antibody levels. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 1979;114:407–10. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-9101-6_65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tew JG, Mandel TE. Prolonged antigen half-life in the lymphoid follicles of specifically immunized mice. Immunology. 1979;37(1):69–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tew JG, Mandel TE, Burgess AW. Retention of intact HSA for prolonged periods in the popliteal lymph nodes of specifically immunized mice. Cellular immunology. 1979;45(1):207–12. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(79)90378-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fischer MB, Goerg S, Shen L, Prodeus AP, Goodnow CC, Kelsoe G, Carroll MC. Dependence of germinal center B cells on expression of CD21/CD35 for survival. Science. 1998;280(5363):582–5. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5363.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Szakal AK, Tew JG. Follicular dendritic cells: B-cell proliferation and maturation. Cancer Res. 1992;52(19 Suppl):5554s–6s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCloskey ML, Curotto de Lafaille MA, Carroll MC, Erlebacher A. Acquisition and presentation of follicular dendritic cell-bound antigen by lymph node-resident dendritic cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2010;208(1):135–48. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mehlhop-Williams ER, Bevan MJ. Memory CD8+ T cells exhibit increased antigen threshold requirements for recall proliferation. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2014;211(2):345–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grigorova IL, Panteleev M, Cyster JG. Lymph node cortical sinus organization and relationship to lymphocyte egress dynamics and antigen exposure. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(47):20447–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009968107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roozendaal R, Mebius RE, Kraal G. The conduit system of the lymph node. International immunology. 2008;20(12):1483–7. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sinha RK, Park C, Hwang IY, Davis MD, Kehrl JH. B lymphocytes exit lymph nodes through cortical lymphatic sinusoids by a mechanism independent of sphingosine-1-phosphate-mediated chemotaxis. Immunity. 2009;30(3):434–46. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen JN, Tewalt EF, Rouhani SJ, Buonomo EL, Bruce AN, Xu X, Bekiranov S, Fu YX, Engelhard VH. Tolerogenic properties of lymphatic endothelial cells are controlled by the lymph node microenvironment. PloS one. 2014;9(2):e87740. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schumann K, Lammermann T, Bruckner M, Legler DF, Polleux J, Spatz JP, Schuler G, Forster R, Lutz MB, Sorokin L, et al. Immobilized chemokine fields and soluble chemokine gradients cooperatively shape migration patterns of dendritic cells. Immunity. 2010;32(5):703–13. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kabashima K, Shiraishi N, Sugita K, Mori T, Onoue A, Kobayashi M, Sakabe J, Yoshiki R, Tamamura H, Fujii N, et al. CXCL12-CXCR4 engagement is required for migration of cutaneous dendritic cells. The American journal of pathology. 2007;171(4):1249–57. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qu C, Edwards EW, Tacke F, Angeli V, Llodra J, Sanchez-Schmitz G, Garin A, Haque NS, Peters W, van Rooijen N, et al. Role of CCR8 and other chemokine pathways in the migration of monocyte-derived dendritic cells to lymph nodes. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2004;200(10):1231–41. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Junt T, Scandella E, Forster R, Krebs P, Krautwald S, Lipp M, Hengartner H, Ludewig B. Impact of CCR7 on priming and distribution of antiviral effector and memory CTL. Journal of immunology. 2004;173(11):6684–93. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.6684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reif K, Ekland EH, Ohl L, Nakano H, Lipp M, Forster R, Cyster JG. Balanced responsiveness to chemoattractants from adjacent zones determines B-cell position. Nature. 2002;416(6876):94–9. doi: 10.1038/416094a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tal O, Lim HY, Gurevich I, Milo I, Shipony Z, Ng LG, Angeli V, Shakhar G. DC mobilization from the skin requires docking to immobilized CCL21 on lymphatic endothelium and intralymphatic crawling. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2011;208(10):2141–53. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pham TH, Baluk P, Xu Y, Grigorova I, Bankovich AJ, Pappu R, Coughlin SR, McDonald DM, Schwab SR, Cyster JG. Lymphatic endothelial cell sphingosine kinase activity is required for lymphocyte egress and lymphatic patterning. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2010;207(1):17–27. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Forster R, Schubel A, Breitfeld D, Kremmer E, Renner-Muller I, Wolf E, Lipp M. CCR7 coordinates the primary immune response by establishing functional microenvironments in secondary lymphoid organs. Cell. 1999;99(1):23–33. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohl L, Mohaupt M, Czeloth N, Hintzen G, Kiafard Z, Zwirner J, Blankenstein T, Henning G, Forster R. CCR7 governs skin dendritic cell migration under inflammatory and steady-state conditions. Immunity. 2004;21(2):279–88. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sallusto F, Palermo B, Lenig D, Miettinen M, Matikainen S, Julkunen I, Forster R, Burgstahler R, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A. Distinct patterns and kinetics of chemokine production regulate dendritic cell function. European journal of immunology. 1999;29(5):1617–25. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199905)29:05<1617::AID-IMMU1617>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dubrot J, Duraes FV, Potin L, Capotosti F, Brighouse D, Suter T, LeibundGut-Landmann S, Garbi N, Reith W, Swartz MA, et al. Lymph node stromal cells acquire peptide-MHCII complexes from dendritic cells and induce antigen-specific CD4(+) T cell tolerance. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2014;211(6):1153–66. doi: 10.1084/jem.20132000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hirosue S, Vokali E, Raghavan VR, Rincon-Restrepo M, Lund AW, Corthesy-Henrioud P, Capotosti F, Halin Winter C, Hugues S, Swartz MA. Steady-state antigen scavenging, cross-presentation, and CD8+ T cell priming: a new role for lymphatic endothelial cells. Journal of immunology. 2014;192(11):5002–11. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tewalt EF, Cohen JN, Rouhani SJ, Engelhard VH. Lymphatic endothelial cells - key players in regulation of tolerance and immunity. Frontiers in immunology. 2012;3:305. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Malhotra D, Fletcher AL, Turley SJ. Stromal and hematopoietic cells in secondary lymphoid organs: partners in immunity. Immunological reviews. 2013;251(1):160–76. doi: 10.1111/imr.12023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cohen JN, Guidi CJ, Tewalt EF, Qiao H, Rouhani SJ, Ruddell A, Farr AG, Tung KS, Engelhard VH. Lymph node-resident lymphatic endothelial cells mediate peripheral tolerance via Aire-independent direct antigen presentation. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2010;207(4):681–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tewalt EF, Cohen JN, Rouhani SJ, Guidi CJ, Qiao H, Fahl SP, Conaway MR, Bender TP, Tung KS, Vella AT, et al. Lymphatic endothelial cells induce tolerance via PD-L1 and lack of costimulation leading to high-level PD-1 expression on CD8 T cells. Blood. 2012;120(24)):4772–82. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-427013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lund AW, Duraes FV, Hirosue S, Raghavan VR, Nembrini C, Thomas SN, Issa A, Hugues S, Swartz MA. VEGF-C promotes immune tolerance in B16 melanomas and cross-presentation of tumor antigen by lymph node lymphatics. Cell Rep. 2012;1(3):191–9. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nichols LA, Chen Y, Colella TA, Bennett CL, Clausen BE, Engelhard VH. Deletional self-tolerance to a melanocyte/melanoma antigen derived from tyrosinase is mediated by a radio-resistant cell in peripheral and mesenteric lymph nodes. Journal of immunology. 2007;179(2):993–1003. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jelley-Gibbs DM, Dibble JP, Brown DM, Strutt TM, McKinstry KK, Swain SL. Persistent depots of influenza antigen fail to induce a cytotoxic CD8 T cell response. Journal of immunology. 2007;178(12):7563–70. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heipertz EL, Davies ML, Lin E, Norbury CC. Prolonged antigen presentation following an acute virus infection requires direct and then cross-presentation. Journal of immunology. 2014;193(8):4169–77. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Strutt TM, McKinstry KK, Kuang Y, Bradley LM, Swain SL. Memory CD4+ T-cell-mediated protection depends on secondary effectors that are distinct from and superior to primary effectors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(38):E2551–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205894109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cerny A, Zinkernagel RM, Groscurth P. Development of follicular dendritic cells in lymph nodes of B-cell-depleted mice. Cell Tissue Res. 1988;254(2):449–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00225818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gonzalez M, Mackay F, Browning JL, Kosco-Vilbois MH, Noelle RJ. The sequential role of lymphotoxin and B cells in the development of splenic follicles. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1998;187(7):997–1007. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.7.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Card CM, Yu SS, Swartz MA. Emerging roles of lymphatic endothelium in regulating adaptive immunity. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2014;124(3):943–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI73316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Acton SE, Farrugia AJ, Astarita JL, Mourao-Sa D, Jenkins RP, Nye E, Hooper S, van Blijswijk J, Rogers NC, Snelgrove KJ, et al. Dendritic cells control fibroblastic reticular network tension and lymph node expansion. Nature. 2014;514(7523):498–502. doi: 10.1038/nature13814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Astarita JL, Cremasco V, Fu J, Darnell MC, Peck JR, Nieves-Bonilla JM, Song K, Kondo Y, Woodruff MC, Gogineni A, et al. The CLEC-2-podoplanin axis controls the contractility of fibroblastic reticular cells and lymph node microarchitecture. Nature immunology. 2015;16(1):75–84. doi: 10.1038/ni.3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tan KW, Chong SZ, Angeli V. Inflammatory lymphangiogenesis: cellular mediators and functional implications. Angiogenesis. 2014;17(2):373–81. doi: 10.1007/s10456-014-9419-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Halin C, Tobler NE, Vigl B, Brown LF, Detmar M. VEGF-A produced by chronically inflamed tissue induces lymphangiogenesis in draining lymph nodes. Blood. 2007;110(9):3158–67. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-066811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Harvey NL, Gordon EJ. Deciphering the roles of macrophages in developmental and inflammation stimulated lymphangiogenesis. Vasc Cell. 2012;4(1):15. doi: 10.1186/2045-824X-4-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kataru RP, Jung K, Jang C, Yang H, Schwendener RA, Baik JE, Han SH, Alitalo K, Koh GY. Critical role of CD11b+ macrophages and VEGF in inflammatory lymphangiogenesis, antigen clearance, and inflammation resolution. Blood. 2009;113(22):5650–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-176776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Onder L, Narang P, Scandella E, Chai Q, Iolyeva M, Hoorweg K, Halin C, Richie E, Kaye P, Westermann J, et al. IL-7-producing stromal cells are critical for lymph node remodeling. Blood. 2012;120(24):4675–83. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-416859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Iolyeva M, Aebischer D, Proulx ST, Willrodt AH, Ecoiffier T, Haner S, Bouchaud G, Krieg C, Onder L, Ludewig B, et al. Interleukin-7 is produced by afferent lymphatic vessels and supports lymphatic drainage. Blood. 2013;122(13):2271–81. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-478073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rondaij MG, Bierings R, Kragt A, van Mourik JA, Voorberg J. Dynamics and plasticity of Weibel-Palade bodies in endothelial cells. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2006;26(5):1002–7. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000209501.56852.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nelson GM, Padera TP, Garkavtsev I, Shioda T, Jain RK. Differential gene expression of primary cultured lymphatic and blood vascular endothelial cells. Neoplasia. 2007;9(12):1038–45. doi: 10.1593/neo.07643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Taylor PR, Pickering MC, Kosco-Vilbois MH, Walport MJ, Botto M, Gordon S, Martinez-Pomares L. The follicular dendritic cell restricted epitope, FDC-M2, is complement C4; localization of immune complexes in mouse tissues. European journal of immunology. 2002;32(7):1888–96. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200207)32:7<1883::AID-IMMU1888>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tew JG, Mandel TE, Miller GA. Immune retention: immunological requirements for maintaining an easily degradable antigen in vivo. The Australian journal of experimental biology and medical science. 1979;57(4):401–14. doi: 10.1038/icb.1979.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Van Breedam W, Pohlmann S, Favoreel HW, de Groot RJ, Nauwynck HJ. Bitter-sweet symphony: glycan-lectin interactions in virus biology. FEMS microbiology reviews. 2014;38(4):598–632. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Malhotra D, Fletcher AL, Astarita J, Lukacs-Kornek V, Tayalia P, Gonzalez SF, Elpek KG, Chang SK, Knoblich K, Hemler ME, et al. Transcriptional profiling of stroma from inflamed and resting lymph nodes defines immunological hallmarks. Nature immunology. 2012;13(5):499–510. doi: 10.1038/ni.2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hajishengallis G, Lambris JD. Microbial manipulation of receptor crosstalk in innate immunity. Nature reviews Immunology. 2011;11(3):187–200. doi: 10.1038/nri2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mazzini E, Massimiliano L, Penna G, Rescigno M. Oral tolerance can be established via gap junction transfer of fed antigens from CX3CR1(+) macrophages to CD103(+) dendritic cells. Immunity. 2014;40(2):248–61. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Allan RS, Waithman J, Bedoui S, Jones CM, Villadangos JA, Zhan Y, Lew AM, Shortman K, Heath WR, Carbone FR. Migratory dendritic cells transfer antigen to a lymph node-resident dendritic cell population for efficient CTL priming. Immunity. 2006;25(1):153–62. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rouhani SJ, Eccles JD, Riccardi P, Peske JD, Tewalt EF, Cohen JN, Liblau R, Makinen T, Engelhard VH. Roles of lymphatic endothelial cells expressing peripheral tissue antigens in CD4 T-cell tolerance induction. Nature communications. 2015;6(6771) doi: 10.1038/ncomms7771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wakim LM, Bevan MJ. Cross-dressed dendritic cells drive memory CD8+ T-cell activation after viral infection. Nature. 2011;471(7340):629–32. doi: 10.1038/nature09863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schorey JS, Cheng Y, Singh PP, Smith VL. Exosomes and other extracellular vesicles in host-pathogen interactions. EMBO reports. 2015;16(1):24–43. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kataru RP, Kim H, Jang C, Choi DK, Koh BI, Kim M, Gollamudi S, Kim YK, Lee SH, Koh GY. T lymphocytes negatively regulate lymph node lymphatic vessel formation. Immunity. 2011;34(1):96–107. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Desch AN, Gibbings SL, Clambey ET, Janssen WJ, Slansky JE, Kedl RM, Henson PM, Jakubzick C. Dendritic cell subsets require cis-activation for cytotoxic CD8 T-cell induction. Nature communications. 2014;5:4674. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Desch AN, Randolph GJ, Murphy K, Gautier EL, Kedl RM, Lahoud MH, Caminschi I, Shortman K, Henson PM, Jakubzick CV. CD103+ pulmonary dendritic cells preferentially acquire and present apoptotic cell-associated antigen. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2011;208(9):1789–97. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Serhan CN, Savill J. Resolution of inflammation: the beginning programs the end. Nature immunology. 2005;6(12):1191–7. doi: 10.1038/ni1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zammit DJ, Cauley LS, Pham QM, Lefrancois L. Dendritic cells maximize the memory CD8 T cell response to infection. Immunity. 2005;22(5):561–70. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]