Abstract

The purpose of this integrative review is to examine and synthesize extant literature pertaining to barriers to substance abuse and mental health treatment for persons with co-occurring substance use and mental health disorders (COD). Electronic searches were conducted using ten scholarly databases. Thirty-six articles met inclusion criteria and were examined for this review. Narrative review of these articles resulted in the identification of two primary barriers to treatment access for individuals with COD: personal characteristics barriers and structural barriers. Clinical implications and directions for future research are discussed. In particular, additional studies on marginalized sub-populations are needed, specifically those that examine barriers to treatment access among older, non-white, non-heterosexual populations.

Keywords: Co-occurring, Dual diagnosis, Substance use disorders, Mental health disorders, Treatment barriers

1. Introduction

An estimated 8.9 million adults in the United States have co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders (COD; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2015). An individual is determined to have COD if they meet clinical criteria for both a mental health disorder and at least one substance use disorder (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2005). Divergent etiological theories exist regarding how these disorders may interact, but a diagnosis of COD requires that at least one mental illness and one substance use disorder (SUD) must be able to be diagnosed independently (Mueser, Drake, & Wallach, 1998; SAMHSA, 2002).

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) defines healthcare access as “the timely use of personal health services to achieve the best possible health outcomes” (Millman, 1993, p.4). Research suggests that individuals with COD access mental health and substance use treatment at disparate rates compared to individuals without such co-morbidities (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2002; Harris & Edlund, 2005). Twenty percent of individuals with a severe mental health disorder will develop a substance use disorder during their lifetime (SAMHSA, 2015). Only 7.4% of these individuals receive treatment for both disorders, and 55% receive no treatment at all (SAMHSA, 2015).

The integrated treatment model has been identified as a best practice for providing treatment to persons with COD. Recognizing the complex nature of COD and the multitude of combinations of mental and substance use disorders, a number of treatment modalities have emerged to address specific manifestations of COD. For example, McGovern and colleagues (2009) have adapted and evaluated a cognitive behavioral therapy program (CBT) for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) for use in addiction treatment programs. Findings suggest that patients who received CBT for PTSD experienced significant reductions in substance use, substance use severity, and PTSD symptoms (McGovern et al., 2009). There is also evidence that modified therapeutic community (MTC) is a promising intervention for persons with COD. A meta-analysis examining the effectiveness of modified therapeutic community (MTC) for persons with COD (offenders, outpatient, homeless) found that MTC was associated with significant treatment effects in substance abuse, mental health, employment, crime, and housing domains (Sacks, Banks, McKendrick, Sacks, 2008; Sacks, McKendrik, Sacks, & Cleland, 2010). The integrated dual disorder treatment model (IDDT) for addictions services has identified a bio-psychosocial approach, motivation enhancement, time-unlimited services, substance use counseling, multidisciplinary teams, and outreach programming as key components of evidence-based treatment across different types of interventions for persons with dual disorders (Kola & Krusynski, 2010). However, as demonstrated by this review, just as each subpopulation of individuals with COD has specific treatment needs, these subpopulations face unique barriers that may prohibit their ability to access such specialized treatment.

Untreated and/or un-identified COD have been associated with increased difficulties with treatment engagement, developing a therapeutic alliance, and adhering to treatment regimens (SAMHSA, 2005). Individuals with untreated COD have increased odds for medical illness, suicide, and early mortality (Chi, Satre, & Weisner, 2006; Rush & Koegl, 2008; SAMHSA, 2015). They frequently present with anxiety, depression, personality disorders, have a history of homelessness or incarceration, and are women (Brooner, King, Kidorf, Schmidt, & Bigelow, 1997; Bassuk, Buckner, Perloff, & Bassuk, 1998; Reiger et al., 1990; Robins, Locke, & Regier, 1991; Rush & Koegl, 2008; Watkins et al., 2004).

Extant studies utilizing national population survey data have examined patterns of treatment utilization among persons with COD (Kessler et al., 1994, 1996; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2008; Mojtabai, Chen, Kaufmann, & Crum, 2014). Kessler and colleagues’ (1994) examination of National Comorbidity Survey data illustrated that of those with lifetime mental disorders and SUD, less than 40% have ever received professional treatment and less than 20% of persons recently diagnosed had received treatment in the previous twelve months. An examination of National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) revealed that treatment entry and utilization may be mediated by race/ ethnicity, and mental disorder type (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2008). Mojtabi and colleagues’ (2014) suggest that perceived barriers to treatment among persons with COD may be related to mental disorder type. While there are numerous studies documenting high service utilization and costs among persons with COD, other studies suggest that this population has markedly lower treatment entry and utilization than those with only substance use or only mental disorders (Curran et al., 2003; Simon & Unutzer, 1999; Verduin, Carter, Brady, Myrick, & Timmerman, 2005). The high prevalence of COD, low treatment entry among this group, known risk factors, and the complexity of the relationship between disorder type, structural challenges, and treatment utilization indicate a need for increased access to treatment for this vulnerable population.

The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act and the Affordable Care Act have mandated increased availability for behavioral health and addiction treatment services (Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, 2008; Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 2010). However, unique barriers to treatment access among individuals with COD may make such service delivery challenging (Druss & Mauer, 2010). Further, barriers to treatment access lead to low treatment entry, underutilization of services, and poorer outcomes (Millman, 1993). A greater understanding of barriers to treatment may facilitate increased treatment access and, therefore, enhanced outcomes for individuals with COD.

Empirical work suggests that individuals with COD access treatment at disparate rates compared to individuals without co-morbidity. In order to gain an extensive understanding of barriers to treatment access for individuals with COD, an integrative review strategy was undertaken. An integrative review strategy allows for the simultaneous examination of diverse methodologies to gain a more comprehensive understanding of a particular topic (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). The aims of this integrative review are to: (1) identify and synthesize the research on barriers to treatment access for individuals with COD, and (2) identify populations among individuals with COD that are underrepresented in the treatment access literature.

2. Methods

Whittemore and Knafl’s (2005) updated methodology for integrative reviews has been used for this study. This updated methodology consists of five stages: problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis, and presentation (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005).

2.1 Search Strategy

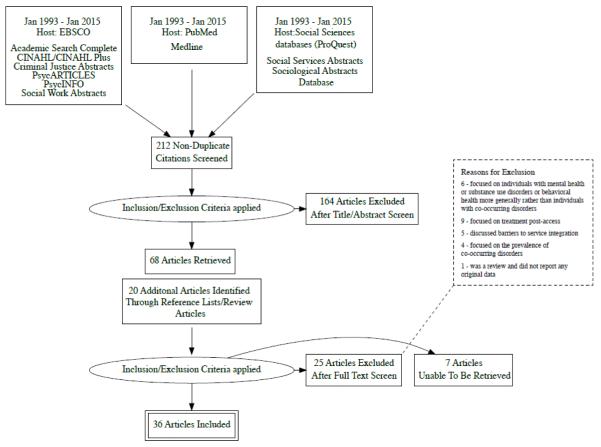

A comprehensive literature search (stage two) was conducted to identify studies that met the following criteria: (a) Peer-reviewed, English language article published between January 1993 and January 2013, (b) related to treatment access, and (c) related to individuals with COD. The terms dual diagnosis and COD began to appear in peer-reviewed literature in the early 1990s. The date range for this review coincides with the emergence of these terms. We chose articles published between 1993 and 2013 because we wanted to identify current barriers to treatment access yet still capture a robust range of studies to examine. Inclusion criteria were broadly defined to enable identification of empirical/non-empirical studies from quantitative and qualitative methodologies and theoretical/conceptual literature focused on treatment access for individuals with COD (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). A research librarian was consulted to discuss potential databases and identify search terms.

In September 2013, ten electronic scholarly databases were searched using three databases search engines: EBSCO (Academic Search Complete, CINAHL/ CINAHL Plus, Criminal Justice Abstracts, PsycARTICLES, PsycINFO, Social Work Abstracts), PubMed (Medline), and Social Sciences Databases/ProQuest (Social Services Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts). As index terms vary across databases and multiple databases were searched, the authors chose to utilize keywords rather than indexing terms. Combinations of the following search terms were used: “co-occurring;” “dual-diagnosis;” “substance abuse;” “mental illness;” “treatment;” “access;” “engagement;” and “client.” An additional search utilizing the same search strategy was conducted in January 2015 to determine if additional relevant studies had been published between September 2013 and January 2015.

2.2 Data evaluation, analysis, and presentation

To address data evaluation, each article examined by the first and second authors using a data evaluation tool. The data evaluation tool utilized a five-point scale to examine the theoretical/methodological rigor of each article and article relevance to the study aims. A score of 1 indicated low theoretical/ methodological rigor and/or relevance to the study aims and a score of 5 indicated high theoretical/ methodological rigor and/or relevance to the study aims (Whittemore &Knafl, 2005). Scores on this measure were above three for all included articles and therefore, no articles were excluded from the study based evaluation tool score.

Data analysis consists of data reduction, data display, data comparison, and conclusion drawing and verification (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005; Miles & Huberman, 1994). The first author critically evaluated each study to identify represented sample populations and barriers to treatment access for individuals with COD (data reduction). A data extraction form that was used to capture study characteristics including sample, geographic location, study methods, article type, and main findings (data display; George, 2000). Data were compared across studies to identify how barriers clustered into themes and subthemes. The second author reviewed the extracted data to ensure studies met inclusion criteria and that thematic conclusions were justified. Disagreements were discussed between both authors until theme consensus was reached. The first and second author cross-checked included articles to verify that categorization of main findings were consistent with the original article (data verification; Whittemore & Knafl, 2005; Miles & Huberman, 1994). Finally, all authors reviewed findings for agreement.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of selected studies

Thirty-six articles meeting inclusion criteria were identified (See Table 1). Twenty-four articles were empirical articles, nine were theoretical/applied articles, two were review articles, and one article was a committee proceeding. A descriptive review by Barrowclough et al. (2006) was included because it presented unpublished data from a randomized control treatment trial. A review by Sterling et al. (2010) was included because it presented unpublished findings from a National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded study, R01AA16204.

Table 1.

Article type, study design, sample, setting, key findings, and identified barriers of reviewed studies.

| Author(s) and Date |

Article type | Study design/ methods |

Sample/ setting | Key Findings | Personal Characteristics Barriers |

Structural Barriers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adler et al., 2014 | Empirical | Mixed methods (survey/ qualitative content analysis with open- ended questions) |

296 staff from 30 VA Community based outpatient clinics |

Rural veterans have fewer resources, lack transportation, and have limited access to assistance and support services. |

✓ | |

| Bethell, Klien, & Peck, 2001 | Empirical | Quantitative/ survey |

Diverse group of adolescents (14- 18) enrolled in commercial or public managed care health plans (n=4,060); 5 sites: 2 N. California; 2 S. California; 1 NY |

Few adolescents receive screening on key issues such as mental health and substance use due to teen access barriers and lack of provider training. |

✓ | |

| Brown & Melchior, 2008 | Empirical | Included 4 studies; 1 was relevant to this review. Included study: quasi- experimental nonequivalent control group design using an intent-to-treat model. |

Data from the National Women with Co- Occurring Disorders and Violence Study (WCDVS) [Participants were women 1 8 years of age or older who met diagnostic criteria for a mental health disorder and a substance use disorder and had a history of violent or traumatic experiences |

Women with higher burden (presence of each of the following: jail within past 30 days, history of homelessness, physical illness or disability, involuntary psychiatric admission, history of child abuse, and current interpersonal abuse) were more likely to leave their program within the first weeks of Treatment program. vulnerable population. |

✓ | |

| Blumenthal et al., 2001 | Empirical | Quantitative/ survey |

National stratified random sample of residents (n=2626) in 8 specialties (internal medicine, pediatrics, family practice, obstetrics/ gynecology, psychiatry, general surgery, orthopedic surgery, and anesthesiology) |

Most psychiatric programs do not provide training in co-morbid disorders and many residents across specialties do not feel confident in discussing substance use issues with patients. |

✓ | |

| Carey et al., 2000 | Empirical | Qualitative/ focus groups |

Services providers (n=12) from a mid-sized city (nursing, counseling, social work, rehabilitation, and psychiatry). |

Lack of specialized services to treat CODs is a barrier (residential/ rehab programs, intensive inpatient, etc.). Finding case managers and other personnel who are trained to work with individuals with CODs is a barrier to integration efforts. |

✓ | |

| Deck & Vander Ley, 2006 | Empirical | Quantitative/ secondary analysis |

5813 Oregon adolescents |

42% of youth with Medicaid utilized mental health services within the same year they received substance abuse treatment while only 8% of non-Medicaid eligible youth accessed mental health services. Among both Medicaid eligible and non-Medicaid eligible youth, Native Americans accessed the least mental health services. Medicaid youths had service utilization much lower than the estimated prevalence of co- occurring disorders. |

✓ | |

| Eliason & Amodia, 2006 | Empirical | Quantitative/ Retrospective chart review |

129 consecutive admissions to a residential program for substance abusers with co- occurring physical and/or mental health disorders |

African-Americans persons had higher mean duration of drug use than their white counterparts, they had fewer mean number of substance abuse treatment admissions and lower treatment success than their White counterparts |

✓ | ✓ |

| Foster et al., 2010 | Empirical | Qualitative analysis of project archives |

11 Collaborative Initiative to Help End Chronic Homelessness (CICH) projects that serve individuals with CODs as they transition from homelessness to permanent- supported housing |

Lack of stable housing among individuals who were homeless and had CODs was a barrier to accessing care. Once the individuals were housed poor previous experiences with service providers and a lack of knowledge about treatment benefits impacted accessing treatment. There was a general lack of expertise for integrated treatment in the communities in the study. Insufficient number of qualified staff/ lack of advanced staff training to address CODs. |

✓ | |

| Godley et al., 2000 | Empirical | Qualitative/ program evaluation |

9 rural counties; 54 individuals with CODs and significant criminal justice involvement participating in a Treatment Alternatives for Street Crimes/Mental Illness Substance Abuse program, which consisted of case management instead of incarceration. |

Participants identified environmental barriers (rurality, transportation, or homelessness) as barriers to access for individuals who need substance abuse and mental health services. |

✓ | |

| Grella, Gil-Rivas, Cooper, 2004 | Empirical | Quantitative/ survey |

Staff and administrators from 10 MH and 15 residential publicly funded SUD treatment programs in Los Angeles (n=260) |

Substance abuse staff indicated significantly poorer rates of accessibility for COD clients in the following areas: excessive waiting lists or delays; red tape involved in treatment enrollment; reasonable cost of services; make clients feel welcome; creaming of clients; MH staff rated themselves lower on availability of evening/ weekend service hours. |

✓ | |

| Hartwell et al., 2014 |

Empirical | Quantitative/ secondary data analysis |

Merged administrative data on all ex- inmates with open mental health cases released from Massachusetts Department of Corrections and two County Houses of Corrections from 2007 to 2009 (N =2,280) and substance abuse treatment outcome data through 2011 |

Males are less likely to seek SA treatment post release than females. Black and Hispanic individuals were less likely to engage in treatment than their white counterparts. Individuals with sexual offenses were less likely to access treatment than those with other offenses. |

✓ | |

| Johnson et al. (2014) | Empirical | Qualitative | 14 staff working with reentering women with CODs in a state prison and aftercare system in Rhode Island |

Providers noted a lack of resources to provide treatment and / or discharge planning as related to women’s inability to access treatment. Long wait times for appointments were also a deterrent to accessing treatment. Women’s lack of trust of institutions or inability to follow through with the treatment plan are also barriers. |

✓ | ✓ |

| Kerwin, Walker-Smith, & Kirby, 2006 | Empirical | Qualitative/ content analysis |

Review of state regulations for licensure/ certification for SUD MH professionals |

All but one state requires a master’s degree for mental health licensing while SA only requires a BA or lower. All but one state requires a master’s degree for mental health licensing while SA only requires a BA or lower. |

✓ | |

| Libby et al., 2007 | Empirical | Quantitative/ secondary analysis |

3325 caregivers of 5,501 children who were the subject of an investigation of child abuse or neglect conducted by Child Protective Services between October 1999 and December 2000 |

American Indian (AI) parents were assessed for mental illness less frequently than others races/ ethnicities even though those assessed had a high prevalence of mental illness. Of those assessed only 20% were referred for service. American Indian parents were assessed more frequently for substance use than their study counterparts. |

✓ | |

| Mericle, 2012 | Empirical (secondary analysis); National sample dataset; 3,972 clients entering outpatient substance abuse treatment at 30 treatment programs |

Quantitative/ secondary analysis |

National sample dataset; 3,972 clients entering outpatient substance abuse treatment at 30 treatment programs |

Overrating and underrating were found among counselors. Counselors failed to rate 32% (n = 691) of clients who reported psychiatric symptoms as needing mental health services, even though 36% (n = 250) of these clients endorsed need for mental health services. Counselor overrating of need for services approximately 4% (n = 68) of clients who did not endorse psychiatric symptoms. |

✓ | |

| Nowotny (2015) | Empirical | Quantitative/ secondary analysis |

n=5180 inmates housed within 286 prisons; data from the 2004 Survey of Inmates in Correctional Facilities |

Whites were more likely to have mental health counseling and substance use treatment as part of their sentence; With regard to treatment utilization 46% of whites reported having received treatment compared to 43% of blacks and 33% of Latinos. |

✓ | |

| Penn, Brooks, & Worsham, 2002 | Empirical | Qualitative/ focus group |

7 women participating in a larger study about COD interventions in Arizona |

Women expressed a desire for welcoming and empathetic staff; client-directed goals; and women only groups’ The women expressed a perception that the system is unjust and unfair (particularly in relation to CPS). |

✓ | ✓ |

| Ro et al., 2006 | Empirical | Quantitative/ survey |

National sample in data sources used in the NHDR (no other sample description given) |

Barriers to mental health and substance abuse services among men of color and low socio- economic status are structural (no insurance, lack of culturally competent services, stigma) and cultural (cultural attitudes about mental illness, substance abuse, or help-seeking. |

✓ | ✓ |

| Rosen, Tolman, & Warner, 2004 | Empirical | Quantitative/ Secondary analysis |

Data from Women’s Employment Study (n=1446) and the National Co-morbidity Survey (n=2379) |

Structural barriers to treatment for women include childcare, cost of treatment, and transportation. Of women who wanted treatment but did not access it, 7.5% cited no childcare, 26.4% cited cost of services or lack of insurance, and 9.4% cited a lack of transportation as a reasons for not accessing treatment; reasons single mothers cited for not seeking treatment despite wanting it included a lack of time (11.3%) or knowledge about where to seek treatment (13.2%) and fear (26.4%). Having two or more disorders increased the respondent’s access to services; the number of barriers predicted service utilization with three or more barriers predicting no service utilization. |

✓ | ✓ |

| Slayter, 2010 | Empirical | Quantitative/ Secondary analysis |

National sample of Medicaid beneficiaries with ID/SA/SMI ages 12 to 99 (N = 5,099) and their counterparts with no ID/SA/SMI (N = 221,875). |

SA treatment utilization suggest that people with ID/SA/SMI were less likely than people with no ID/SA/SMI to initiate (26 percent compared with 32 percent) and engage (51 percent compared with 54 percent). |

✓ | |

| Smelson et al., 2005 | Empirical | Quantitative/ 8 week naturalistic feasibility study |

59 subjects recently hospitalized within the VA system with a mental illness SUD who were offered time limited case management (TLC). TLC treatment group (n = 26); comparison group (n = 33). |

Individuals in TLC program were more likely to engage and adhere to day treatment and meds than individuals who did not suggesting time limited case management assisting in the linkage of care upon discharge may improve treatment initiation and adherence post- hospitalization. |

✓ | |

| Smelson et al., 2012 | Empirical | Quantitative/ prospective randomized trial |

102 Veterans in New Jersey: (1) met current DSM-IV or ICD diagnostic criteria for a substance abuse or dependence disorder or poly- substance use, (2) had used drugs or alcohol within the past 3 months, (3) had a co-occurring schizophrenia spectrum or bipolar I disorder. |

Individuals in the TLC intervention (described above) attended more inpatient sessions and more sessions post discharge that those in a matched comparison group. |

✓ | |

| Watkins et al., 2001 | Empirical | Quantitative; secondary analysis |

Nationally representative sample; 9,585 randomly selected participants of the Community Tracking study were used as a sample for the Healthcare for Communities study. |

72% of persons with COD did not receive specialty MH/ SUD care in the previous 12 months. Perceived need for care was associated with receipt of care. |

✓ | |

| Watkins et al., 2004 | Empirical | Quantitative/ cross-sectional |

n=195; individuals from 3 publicly funded Los Angeles outpatient substance abuse treatment facilities that served primarily low-income and ethnic minority communities. All screened positive for a probable mental health disorder, reported they had a mental health problem, or were currently taking medication for a mental or emotional problem. |

Half of the individuals in the sample who screened positive for CODs reported that they had never received MH treatment and 1/3 reported this was their first time in SUD Treatment. |

✓ | |

| Sterling et al., 2010 | Review | Adolescents | Medical providers have low referral rates to SA treatment with 74% referring primarily to psychiatry departments and 61% referring to MH treatment and cite lack of knowledge appropriate referral as a barrier to identifying substance abuse in adolescents. Pediatricians report sensitivity about discussing substance abuse with their patients compared to other behavioral problems. Under- identification decreases the likelihood that many adolescents receive the treatment they need. |

✓ | ✓ | |

| Bellack & DiClemente, 1999 | Applied | Patients with Schizophrenia |

Confrontational style of traditional substance abuse programs is contraindicated for people with psychosis. Existing treatment models do not address specific learning and performance associated with schizophrenia; Individuals with co-occurring schizophrenia and substance use disorders have impaired cognition, lack social interaction skills, and have low energy levels and low motivation; these effects of their disease create barriers to accessing treatment. |

✓ | ✓ | |

| Clarke et al., 2008 |

Applied | Insurance benefits are more generous for mental health than for substance use, so substance use disorders are at risk of being under diagnosed and untreated; Individuals with CODs are shuttled between siloed systems that can only treat one type of disorder, or receive treatment in segregated service systems that do not have capacity to share information. |

✓ | |||

| Drake et al., 2004 | Applied | Distress and disorganization due to dual disorders may impact an individual’s ability to engage in services and follow through with a treatment plan. |

✓ | |||

| Green et al., 2007 | Applied/ Case study |

Patients with Schizophrenia |

Separate mental health and substance abuse training programs and service delivery systems result deficits in provider knowledge about CODs; Individuals with co-occurring disorders including psychosis are extremely vulnerable because their substance abuse often exacerbates mental health symptoms, creates psychosocial instability and decreases their ability to seek and access treatment. |

✓ | ✓ | |

| Pincus, 2007 | Committee Proceeding |

Lack of cooperation, provider type, restrictions on information sharing, and a deficit in the use of information technology force individuals to seek care from multiple service systems and disparate providers |

✓ | |||

| Barrowclough et al., 2006 | Review | Descriptive review |

Patients with Psychosis |

Individuals with psychosis may have low motivation to change (associated with their psychosis) |

✓ | |

| Hester, 2004 | Theoretical | Rural primary care settings |

Substance abuse and mental health programs are often very limited in rural areas. |

✓ | ||

| Kuehn, 2010 | Theoretical | Separate payment systems for substance use and medical care is a key barrier. |

✓ | |||

| Libby & Riggs, 2005 | Theoretical | Adolescents | MH care is available at primary care physicians and psychiatrists while SUD Treatment is offered almost exclusively at specialty facilities. |

✓ | ||

| Little, 2001 | Theoretical | Abstinence only programs may be a deterrent to treatment access. Programs that are focused on harm reduction increase the likelihood an individual accesses treatment. Level of functioning such as social skills, emotional capacity, and ego strength may inhibit an individual’s ability to participate in traditional treatment modalities. Individuals who are in crisis might also be too psychologically vulnerable to participate in treatment. |

✓ | ✓ | ||

| Hawkins, 2009 | Theoretical/ Applied |

Adolescents | Perceived stigma by both adolescents and their parents may act as a barrier to treatment seeking. There is a lack of comprehensive, developmentally appropriate treatment services for adolescents with CODs. |

✓ |

Note. Any omissions in study design, setting, or sample are because these components were not included in the article. COD= Co-occurring mental health and substance use disorder; MH= Mental health; SUD= Substance use disorder; SA= Substance abuse; ID= Intellectual disabilities.

3.1.2. Populations represented in the literature

Of the 36 included articles, 19 focused on specific subpopulations of individuals with COD. Five of these studies focused on adolescents; four were related to women with COD; four focused on individuals involved in the criminal justice system; three studies focused on veterans. Three studies focused on individuals with SUDs and severe and persistent mental illness (SPMI). Two studies focused on treatment access for men of color or ethnic minorities and two studies focused on individuals with low socio-economic status. Individuals experiencing homelessness; and individuals with intellectual disabilities were represented with one study each.

3.2 Findings

Two broad categories of barriers to service access were identified from an analysis of the literature: personal characteristics barriers and structural barriers.

3.2.1. Personal characteristics barriers

Fifteen of 36 articles described personal characteristics barriers to treatment access. Personal characteristics barriers identified in this review were related to personal vulnerabilities and personal beliefs. Personal vulnerabilities barriers include individual characteristics, knowledge, and skills that may impede treatment access (Tawil, Vester, & O’Reilly, 1995). Personal beliefs barriers are attitudinal, motivational, and belief-based impediments that formally or informally inhibit an individual’s ability to mobilize personal resources to access care (Kalmuss & Fennelly, 1990; Venner et al., 2012).

3.2.1.1. Personal vulnerabilities

Symptoms associated with concurrent mental illness and SUDs may exacerbate individual vulnerability and act as barriers to treatment access. For example, individuals with COD including psychosis are extremely vulnerable because their substance use often worsens mental health symptoms, creates psychosocial instability, lowers motivation, and decreases their ability to seek and access treatment (Green, Drake, Brunette, & Noordsy, 2007; Barrowclough, Haddock, Fitzsimmons, & Johnson, 2006). Individuals with co-occurring schizophrenia and SUDs may have impaired cognition, lack social interaction skills, and have low energy levels and low motivation (Bellack & DiClemente, 1999; Little, 2001). Their level of functioning such as emotional capacity and ego strength may inhibit their ability to participate in traditional treatment modalities (Little, 2001). Individuals who are in crisis might also be too psychologically vulnerable to participate in treatment. (Little, 2001). Further, distress and disorganization due to dual disorders may affect an individual’s ability to engage in services and follow through with a treatment plan (Drake, Morse, Brunette, & Torrey, 2004). The impact of these symptoms is further intensified among individuals with intellectual disabilities, SUDs, and severe mental illness. A study of 5,099 Medicaid beneficiaries found that individuals who were diagnosed with intellectual disabilities, SUDs, and severe mental illness were less likely than people with none of these diagnoses to initiate (26% compared with 32%) or engage in SUD treatment (51% compared with 54%; Slayter, 2010).

3.2.1.3 Personal beliefs

Personal beliefs were identified as a barrier to treatment access across multiple populations. These included personal beliefs about treatment providers, cultural beliefs, and stigma related to substance abuse and mental illness. In two qualitative studies, both women diagnosed with COD and service providers working with women with COD who were criminal justice involved cited lack of trust of institutions as a barrier to the women accessing treatment (Johnson, 2014; Penn, Brooks, & Worsham, 2002). Similarly, 26.4% of single mothers receiving welfare cited fear as a reason for not accessing treatment despite wanting it (Rosen, Tolman, & Warner, 2004).

Ro, Casares, Treadwell, and Braithwaite (2006) argue that cultural attitudes and beliefs about mental illness, substance abuse, and help-seeking are barriers to treatment among men of color and low socioeconomic status. For marginalized individuals, such as people of color or lower socioeconomic status, diagnosis of mental illness and/or SUDs adds an additional burden of stigma to their already marginalized status (Eliason & Amodia, 2006). Stigma also plays a role in adolescents’ ability to access treatment. Perceived stigma by both adolescents and their parents may act as a barrier to treatment seeking (Hawkins, 2009). Compounding these beliefs are provider beliefs about stigma associated with substance use. Sterling et al. (2010) note that provider beliefs about stigma associated with substance use often leads medical practitioners to diagnose adolescents with psychiatric disorders instead of SUDs due to a fear of jeopardizing adolescents’ futures.

3.2.2. Structural Barriers

Thirty of 36 articles described structural barriers to treatment access. Structural barriers are factors and practices rooted in social, political, legal, and service systems “that systematically hinder access [to care] to certain groups of people” (Kalmuss & Fennelly, 1990, p. 215; Sumartojo, 2000). These barriers are related to the availability of services, how services are provided, service location, and the organizational configuration of service providers (Millman, 1993). In addition, structural barriers include financial factors such as insurance coverage and reimbursement levels (Millman, 1993). In this integrative review, the following structural barriers were identified: service availability, disorder identification, provider training, service provision, racial/ ethnic disparities, and insurance/ policy related barriers.

3.2.2.1. Service availability

A primary barrier to treatment access for individuals with COD is service availability. In general, there is a lack of specialized services to treat individuals with COD (residential or rehabilitation programs, intensive inpatient care, etc.). Focus groups with clinicians working in a psychiatric clinic from a variety of disciplines reported needing additional training or additional staff that specialized in COD (Carey, Purnine, Maisto, Carey, & Simons, 2000). In rural and resource-poor settings, this lack of specialized services is exacerbated. Generally, substance abuse and mental health programs are very limited in rural areas and (Hester, 2004). Geographic proximity to services and lack of transportation or resources to obtain transportation to reach these limited services are commonly cited in the literature as a barrier to treatment access (Adler, Pritchett, Kauth, & Mott, 2014; Godley et al., 2000; Rosen et al., 2004). In particular, rural veterans and individuals who are homeless or criminal justice-involved have fewer resources, lack transportation, and have limited access to assistance and support services (Adler et al., 2014; Godley et al., 2000). On an online survey of 296 staff providing services to veterans who were homeless, 53% cited fewer resources, 29% cited lack of transportation, and 20% cited limited access to support and services as barriers to substance use and mental health services (Adler et al., 2014). Another study of 11 projects that served individuals with COD as they transition from homelessness to permanent- supported housing found that even once individuals were stabilized in housing there was still a general lack of expertise for integrated treatment in the communities studied (Foster, LeFauve, Kresky-Wolff, & Rickards, 2010).

3.2.2.2. COD Identification

Another barrier to treatment access for individuals with COD is disorder identification. It is common that practitioners may identify a substance use disorder or a mental health disorder but not the co-occurrence of both. Findings suggest under-identification rates are particularly high among adolescents, individuals from low socioeconomic backgrounds, and racial/ ethnic minorities. COD identification is a significant barrier to treatment access for adolescents with few adolescents receiving mental health and substance use screening in medical settings. In a review of the literature about treatment access for adolescents, Sterling, Weisner, Hinman, and Parthasarathy (2010) report that comprehensive screening and assessment are not commonly used in psychiatric or primary care settings. One study of 4,060 adolescents enrolled in managed care organizations found that overall adolescents receive preventative, counseling, and screening services at 20%-50% of optimum rates (Bethell, Klein, Peck, 2001). Under-identification of both substance use and mental health disorders in primary care and other systems decreases the likelihood many adolescents receive the treatment they need (Sterling et al., 2010).

Under-identification of COD has also been documented among racial/ethnic minorities and individuals from low socioeconomic backgrounds. A study of 195 individuals from three publically funded substance abuse facilities that primarily served low-income racial/ethnic minorities found that half of the individuals in the sample who screened positive for COD reported that they had never received mental health treatment (Watkins, 2004). In addition, one-third of the participants reported this was their first substance abuse treatment episode highlighting the need for increased screening.

3.2.2.3. Provider training

Contributing to under-identification of COD is a lack of sufficient training to identify both mental health and SUDs (Carey et al., 2000; Foster et al., 2010; Green et al., 2007). Among medical practitioners, most psychiatric programs do not provide training in co-morbid disorders and many family practice residents do not feel confident in discussing substance use issues with their patients (Blumenthal, Gokhale, Campbell, & Weissman, 2001). A study of 2626 medical residents completing their last year of training found that approximately 1 in 10 residents in eight specialties felt unprepared to manage patients with substance use disorders and/or depression (Blumenthal et al., 2001). Another deficit in medical provider training is related to knowledge about community mental health and substance use referral sources. Medical providers often cite a lack of knowledge about appropriate referral sources as a barrier to identifying substance abuse in adolescents (Sterling et al., 2010).

With regard to behavioral health practitioners, mental health professionals may be more qualified to identify COD than SUD professionals (Kerwin, Walker-Smith, & Kirby, 2006). It is important to increase the rate that individuals in treatment for mental health problems are screened and referred for SUD treatment (Clark et al., 2008). At the same time, SUD treatment clinicians need to be able to screen, assess for, treat, or refer those with mental health disorders as well (Clark et al., 2008). Disparate training and licensure requirements may influence providers’ capacity to identify COD. All but one state requires a master’s degree for mental health licensing while licensed substance abuse clinicians are only required to have a bachelor’s degree or in some states less education (Kerwin et al., 2006). Interprofessional training may increase access to treatment by increasing provider capacity for mental health and SUD identification (Hawkins, 2009).

3.2.2.4. Service provision

Another structural barrier to treatment access for individuals with COD is service provision. Service provision includes service barriers such as organizational red tape and barriers related to treatment provision, such as the way that treatment is provided. The service barriers an individual encounters during their pre-treatment phase has the potential to impact the accessibility of treatment services. In a study examining administrator and staff perceptions of integrated treatment systems for COD in Los Angeles county, Grella, Gil-Rivas, and Cooper (2004) found that substance abuse staff indicated significantly poorer rates of accessibility for clients with COD due to excessive waiting lists or delays; red tape involved in treatment enrollment; failure to make clients feel welcome; or provider tendency to select clients based on potential for positive treatment outcomes. A study examining perspectives of prison and after care providers had similar findings (Johnson et al., 2014). Service providers for women with COD who are incarcerated describe long wait times for appointments as a deterrent to treatment and a lack of discharge planning as related to women’s inability to access treatment (Johnson et al., 2014).

Treatment needs vary by individual and population characteristics. As such, traditional treatment modalities may act as a deterrent for some individuals with COD. For individuals with psychosis, the confrontational treatment style of traditional substance abuse programs is contraindicated (Bellack & DiClemente, 1999). For those with schizophrenia, traditional approaches are often a deterrent because programs fail to address specific learning and performance deficits characteristic to schizophrenia (Bellack & DiClemente, 1999). For adolescents, treatment agencies may be unprepared to treat youth or lack comprehensive, developmentally appropriate treatment services for adolescents with COD (Sterling et al., 2010). Further limiting treatment access, youth are often referred to SUD treatment with the stipulation that they will complete treatment and achieve a period of abstinence before their mental health issue will be evaluated or addressed (Libby & Riggs, 2005). Lack of sensitivity to individual cultural needs (e.g. culturally-specific services) may also play a role in whether or not an individual with COD accesses treatment. A retrospective chart review of 129 consecutive admissions found that while African-Americans persons had higher mean duration of drug use than their white counterparts, they had fewer mean number of substance abuse treatment admissions and lower treatment success than their White counterparts (Eliason & Amodia, 2006). Eliason and Amodia (2006) suggest that lack of culturally sensitive services or culturally competent staff may be a reason for the underrepresentation of people of color and ethnic minorities in substance abuse and mental health treatment.

There are also a number of gender-specific factors that may inhibit treatment access. One factor consistently mentioned by women as a barrier to treatment access is a lack of treatment services that provide onsite childcare. An examination of data collected during the Women’s Employment Study and the National Co-morbidity study found that among single mothers who received welfare and wanted substance abuse and/or mental health treatment but did not access it, 7.5% cited not having childcare as a reason for not accessing services (Rosen et al., 2004). In addition, some research suggests that women have gender-specific treatment preferences. In a qualitative study examining the treatment concerns of women with COD, women expressed a desire for treatment environments that had welcoming and empathetic staff; client-directed goals; and women only groups (Penn et al., 2002). Treatment service providers that do not address these gender-specific preferences in treatment provision may deter women from accessing treatment services.

3.2.2.5. Racial and Ethnic Disparities

There are notable racial and ethnic disparities in treatment access for individuals with COD. A survey of drug dependent inmates in correctional facilities determined Whites were more likely to have been diagnosed with a co-occurring mental health disorder and were more likely to have mental health counseling and substance use treatment as part of their sentence than non-whites (Nowotny, 2015). There are similar racial and ethnic disparities in treatment referral. An examination of data from caregivers who participated in the National Study of Child and Adolescent Well- Being (NSCAW) longitudinal study found that Native American parents were assessed for mental illness less frequently than other races/ ethnicities even though they had the highest prevalence of mental illness and emotional problems (Libby et al., 2007). In addition, only 20% of Native American caregivers that were assessed for mental illness were referred for service (Libby et al., 2007). Conversely, Native American parents were assessed more frequently for substance use than their study counterparts, which may be related to assumptions about the substance use treatment needs of Native Americans based on stereotypical assumptions that they have a high prevalence of substance use issues (Libby et al., 2007). This is consistent with Eliason and Amodia (2006) who suggest that societal oppression may contribute to differential, inaccurate, and under diagnosis of individuals who are racial/ethnic, gender, or sexual minorities. These racial and ethnic disparities in mental health and substance abuse treatment access are not bound by age. A study of administrative data of Oregon youth found that Native American youth accessed mental health services less frequently compared to other youth, indicating that disparities in access to mental health services for Native Americans is not limited to adults (Deck & Vander Ley, 2006).

3.2.2.6. Insurance/ policy-related barriers

Insurance and coverage policies act as barriers to treatment access. Lack of insurance among men of color and low socioeconomic status hinder treatment access (Ro et al., 2006). Among single mothers who receive welfare who wanted substance abuse and/or mental health treatment but did not access it, 26.4% cited cost of services or lack of insurance as a reason for not accessing treatment (Rosen et al., 2004). For individuals who have insurance, insurance benefits are often more generous for mental health services than for substance use treatment, so SUDs are at risk of being under diagnosed and untreated (Clark et al., 2008). In addition, some Medicaid programs do not cover SUD treatment, which also creates barriers to access (Foster et al., 2010).

Conversely, in some states, Medicaid may facilitate substance use and mental health treatment access for individuals with COD, with those without Medicaid accessing services at much lower rates than those with Medicaid coverage. A study of administrative data for 5,813 Oregon youth found that after controlling for group differences and system changes over time, 42% of youth with Medicaid utilized mental health services within the same year they received substance abuse treatment while only 8% of non-Medicaid eligible youth accessed mental health services (Deck & Vander Ley, 2006). Despite these seemingly high rates of access for Medicaid youths, the Oregon study demonstrated that Oregon youth had service utilization much lower than the estimated prevalence of COD further illustrating a service gap for youth with COD (Deck & Vander Ley, 2006). Lack of coverage for prevention and early intervention treatment decreases treatment access for adolescents until their symptoms escalate (Sterling et al., 2010). Insurance overage limits or time-limited services further decreases access to needed services (Sterling et al., 2010). Additionally, the restrictions associated with publically funded services, such as specialized programs for specific populations (e.g. pregnant women) and lifetime or yearly limits on access to care, create barriers to access (Sterling et al., 2010). Health plans interact in a variety of ways to produce economic incentives or disincentives for integrated care (Libby & Riggs, 2005). Treatment access is increased by financial incentives from integrated service systems for early detection and intervention (Libby & Riggs, 2005).

4. Discussion

4.1 Main findings

The overall aim of this integrative review was to identify barriers to treatment access for individuals with COD and to identify populations in need of such treatment that are underrepresented in the literature. Two primary types of barriers to treatment access for individuals with COD were identified: personal characteristics barriers and structural barriers. Nine sub-populations were identified as underrepresented in the literature, including adolescents, women, men of color/ ethnic minorities, veterans, individuals with low socio-economic status, individuals with SPMI, individuals who are involved in the criminal justice system or are experiencing homelessness, and individuals with intellectual disabilities. Notably absent from the literature were studies examining treatment access for individuals who identify as LGBTQ, older adults, and individuals of Hispanic descent. With only 7.4% of individuals with COD receiving treatment for both disorders, and 55% receiving no treatment at all, it is imperative we identify and address barriers to treatment access to improve outcomes for this underserved population (SAMHSA, 2015).

4.2 Clinical implications

This is the first review of its kind to integrate extant literature on barriers to treatment access among individuals with co-occurring mental health and SUDs. Consistent with Kohn, Corrigan, and Donaldson (2001), findings from this review suggest one strategy to increase accessibility to treatment for individuals with COD may be to shift towards a more client-centered approach to service provision. This not only includes specialized treatment programs that generally meet the needs of individuals with COD but also programming that considers different client characteristics such as mental and substance use disorder type and combination (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2008; McGovern et al., 2009; Mojtabi et al., 2014). For example, individuals with SPMI may be more likely to access treatment that utilizes a less confrontational treatment modality such as harm reduction programs (Bellack & DiClemente, 1999). Increased availability of developmentally appropriate treatment options might increase treatment access among adolescents (Sterling et al., 2010). Further, approaches that require abstinence prior to mental health assessment may create missed opportunities to engage clients with dual disorders (Libby & Riggs, 2005).

Treatment services with substantial entry barriers are also a significant deterrent to treatment access. Reducing organizational red tape and developing pre-treatment programming that can engage clients while they wait for availability of intake and treatment appointments may increase treatment enrollment (Grella et al., 2004; Johnson et al., 2014). Flexible service provision, such as increasing evening and weekend hours or providing satellite or home-based services for individuals in rural areas, may address transportation challenges. Finally, as is well documented in the literature, integrated service systems with integrated communication may enhance treatment access (see review Drake et al., 2004; Kola & Krusynski, 2010). Single-entry point and co-located and/or integrated assessment, treatment, and case management services are key components of increasing treatment access among this vulnerable population (Drake et al., 2004; Minkoff, 2014). A recent qualitative study that examined barriers to client-centered treatment in rural communities found that flexible, community-based, wrap-around services that address substance use, mental health, and basic needs in an integrated way may increase the likelihood of individuals’ accessing treatment when significant barriers such as transportation, childcare, and geographic proximity to services in resource poor, rural communities are present (Browne et al., 2015). Integrated services must be flexible and client-centered to maximize treatment accessibility for individuals with COD, particularly those who face structural barriers to treatment (Kola & Krusynski, 2010).

Findings from this review also indicated that another major barrier to accessing services for individuals with COD is a lack of capacity to identify substance use and mental health disorders among medical, mental health, and substance abuse service providers (Carey et al., 2000; Foster et al., 2010; Green, et al., 2007; Blumenthal et al., 2001). Development of certification and training standards for clinical assessment of COD for substance abuse, mental health, and medical professionals may increase dual disorder identification (Kerwin et al., 2006; Hawkins, 2009). Further, increased communication and collaboration among medical, mental health, and substance abuse service providers may increase dual disorder identification, inter-professional knowledge with regard to dual disorders, and treatment referrals (Sterling et al., 2010). Racial and ethnic disparities in screening and referral also serve as a barrier to access among minority populations (Nowotny, 2015; Libby et al., 2007; Deck & Vander Ley, 2006). Universal screening across service settings for both mental health and SUDs may decrease inconsistent and biased referrals and increase identification of dual disorders among minority populations. Compounding disparities in screening and referral among minority populations is a lack of culturally specific services and/or diverse, culturally competent staff (Eliason & Amodia, 2006). Targeted workforce development and recruitment of diverse substance abuse and mental health professionals may address cultural barriers to treatment access.

4.3 Limitations and directions for future research

There are limitations to this integrative review that merit attention. Differing research designs and sampling frames between studies prevented cross-study statistical comparison (Cooper, 1998). It is also possible that relevant studies may have been omitted due to the search strategy and inclusion criteria (Conn et al., 2003; Avenell, Handoll, & Grant, 2001; Whittemore, 2005). Focusing only on barriers to treatment access for individuals with COD, this review is unable to compare its findings to barriers to treatment access for individuals with only substance use disorders and barriers for individuals with only mental health disorders. Although some research has compared outcomes for individuals with COD to individuals with a single substance use or mental health disorder (Seay & Kohl, 2015), this comparison was outside the scope of this review. Future work can compare barriers to treatment across these groups (COD, mental health disorders only, SUDs only). Finally, as this review was limited to articles published in peer-reviewed publications, this review is susceptible to publication bias. It is possible that other articles examining treatment access for individuals with COD exist but have not been published due to factors such as submission and publication lag, insignificant findings, or a lack of resources to publish the study (Bartolucci & Hillegass, 2010). The present results should be interpreted within the context of these limitations.

Additional research examining barriers to treatment access for individuals with COD is needed. In particular, additional research should be conducted to further examine barriers to treatment access for non-White, non-heterosexual populations with COD. Notably absent from the literature were studies examining treatment access for individuals who identify as LGBTQ, older adults, individuals of Hispanic descent, and individuals with tri-morbid chronic medical conditions or trauma and COD. Studies that explore differences in treatment access across these underrepresented subpopulations of individuals with COD are needed to ensure more client-centered care. More studies are also needed that examine the impact of cultural norms and environmental factors as barriers to treatment access for individuals with COD. In addition, with the inclusion and expectation of behavioral health services now nationally mandated to be in accord with the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, future research examining access to care for individuals with COD will be needed to determine the role this new policy will have on possibly improving or decreasing such access.

Highlights.

Co-occurring disorders are associated with low service use and negative outcomes.

We examine treatment access barriers for persons with co-occurring disorders.

Treatment access barriers include personal characteristics and structural barriers.

Few studies examine access barriers for older, non-white, non-heterosexual persons.

Studies on treatment access barriers for underrepresented groups are needed.

Figure 1.

Search Strategy

Acknowledgments

Disclosures

This Project was supported by contract number A201611015A with the South Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (SCDHHS). This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (F31DA034442, K. Seay, PI; 5T32DA015035). Points of view in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of SCDHHS or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

(* Indicates inclusion in integrative review)

- Adler G, Pritchett LR, Kauth MR, Mott J. Staff perceptions of homeless veterans’ needs and available services at community-based outpatient clinics. Journal Of Rural Mental Health. 2014 doi:10.1037/rmh0000024* [Google Scholar]

- Avenell A, Handoll HH, Grant AM. Lessons for search strategies from a systematic review, in the Cochrane Library, of nutritional supplementation trials in patients after hip fracture. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2001;73(3):505–510. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrowclough C, Haddock G, Fitzsimmons M, Johnson R. Treatment development for psychosis and co-occurring substance misuse: A descriptive review. Journal of Mental Health. 2006;15(6):619–632. * [Google Scholar]

- Bassuk EL, Buckner JC, Perloff JN, Bassuk SS. Prevalence of mental health and substance use disorders among homeless and low-income housed mothers. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155(11):1561–1564. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.11.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolucci AA, Hillegass WB. Evidence-Based Practice: Toward Optimizing Clinical Outcomes. Springer; Berlin Heidelberg: 2010. Overview, strengths, and limitations of systematic reviews and meta-analyses; pp. 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bellack AS, DiClemente CC. Treating substance abuse among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50:75–80. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.1.75. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethell C, Klein J, Peck C. Assessing health system provision of adolescent preventive services: The Young Adult Health Care Survey. Medical Care. 2001;39(5):478–490. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200105000-00008. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal D, Gokhale M, Campbell EG, Weissman JS. Preparedness for clinical practice: Reports of graduating residents at academic health centers. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;286(9):1027–1034. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.9.1027. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooner RK, King VL, Kidorf M, Schmidt CW, Bigelow GE. Psychiatric and substance use comorbidity among treatment-seeking opioid abusers. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54(1):71–80. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830130077015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown VB, Melchior LA. Women with co-occurring disorders (COD): Treatment settings and service needs. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2008:365–376. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2008.10400664. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne T, Priester MA, Clone S, Iachini A, DeHart D, Hock R. Barriers and facilitators to substance use treatment in the rural south: A qualitative study. The Journal of Rural Health. 2015 doi: 10.1111/jrh.12129. DOI 10.1111/jrh.12129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Purnine DM, Maisto SA, Carey MP, Simons JS. Treating substance abuse in the context of severe and persistent mental illness: Clinicians perspectives. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2000;19(2):189–198. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00094-5. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo JE, Carrillo VA, Perez HR, Salas-Lopez D, Natale-Pereira A, Byron AT. Defining and targeting health care access barriers. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2011;22(2):562–575. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment . Substance abuse treatment for persons with co-occurring disorders. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment . Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Addiction in Opioid Treatment Programs. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); Rockville (MD): 2005. Chapter 12. Treatment of Co-Occurring Disorders. (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 43.) Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64163/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi FW, Satre DD, Weisner C. Chemical Dependency Patients with Cooccurring Psychiatric Diagnoses: Service Patterns and 1-Year Outcomes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30(5):851–859. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Children Now Partners in transition: Adolescents and managed care. 2000 Apr; Retrieved from http://www.childrennow.org/uploads/documents/partners_2000.pdf.

- Civic Impulse H.R. 1424 — 110th Congress: Paul Wellstone Mental Health and Addiction Equity Act of 2007. 2015 Retrieved from https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/110/hr1424.

- Clark H, Power A, LeFauve CE, Lopez EI. Policy and practice implications of epidemiological surveys on co-occurring mental and substance use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;34(1):3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.032. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.032* [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn VS, Isaramalai SA, Rath S, Jantarakupt P, Wadhawan R, Dash Y. Beyond MEDLINE for literature searches. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2003;35(2):177–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2003.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HM. Integrating research: A guide for literature review. 2nd ed Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HM. Synthesizing research: A guide for literature reviews. Vol. 2. Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Curran GM, Sullivan G, Williams K, Han X, Collins K, Keys J, Kotrla KJ. Emergency department use of persons with comorbid psychiatric and substance abuse disorders. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2003;41(5):659–667. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deck D, Vander Ley K. Medicaid eligibility and access to mental health services among adolescents in substance abuse treatment. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57(2):263–265. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.2.263. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Morse GG, Brunette MF, Torrey WC. Evolving U.S. service model for patients with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorder. Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 2004;16(1):36–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5215.2004.0059.x. doi:10.1111/j.1601-5215.2004.0059.x* [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Mueser KT, Brunette MF, McHugo GJ. A review of treatments for people with severe mental illnesses and co-occurring substance use disorders. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2004;27(4):360. doi: 10.2975/27.2004.360.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druss BG, Mauer BJ. Health care reform and care at the behavioral health: Primary care interface. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61(11):1087–1092. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.11.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliason M, Amodia D. A descriptive analysis of treatment outcomes for clients with co-occurring disorders: The role of minority identifications. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2006;2(2):89. doi:10.1300/J374v02n02̱05* [Google Scholar]

- Foster S, LeFauve C, Kresky-Wolff M, Rickards L. Services and supports for individuals with co-occurring disorders and long-term homelessness. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2010;37(2):239–251. doi: 10.1007/s11414-009-9190-2. doi:10.1007/s11414-009-9190-2* [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godley SH, Finch M, Dougan L, McDonnell M, McDermeit M, Carey A. Case management for dually diagnosed individuals involved in the criminal justice system. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2000;18(2):137–148. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(99)00027-6. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/61663628?accountid=14605* [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George SA. Barriers to breast cancer screening: an integrative review. Health Care for Women International. 2000;21(1):53–65. doi: 10.1080/073993300245401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green A, Drake R, Brunette M, Noordsy D. Schizophrenia and co-occurring substance use disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164(3):402–408. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.3.402. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Gil-Rivas V, Cooper L. Perceptions of mental health and substance abuse program administrators and staff on service delivery to persons with cooccurring substance abuse and mental disorders. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2004;31(1):38–49. doi: 10.1007/BF02287337. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Edlund MJ. Use of mental health care and substance abuse treatment among adults with co-occurring disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56(8):954–959. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.8.954. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell S, Deng X, Fisher W, Siegfriedt J, Roy-Bujnowski K, Johnson C, Fulwiler C. Predictors of accessing substance abuse services among individuals with mental disorders released from correctional custody. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2013;9(1):11–22. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2012.749449. * [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM, Narrow WE, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Racial/ethnic disparities in service utilization for individuals with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders in the general population: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69(7):1112–1121. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins EH. A tale of two systems: Co-occurring mental health and substance abuse disorders treatment for adolescents. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:197–227. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163456. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hester RD. Integrating behavioral health services in rural primary care settings. Substance Abuse. 2004;25(1):63–64. doi: 10.1300/J465v25n01_10. doi:10.1300/J465v25n01_10* [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JE, Schonbrun YC, Peabody ME, Shefner RT, Fernandes KM, Rosen RK, Zlotnick C. Provider experiences with prison care and aftercare for women with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders: Treatment, resource, and systems integration challenges. The Journal Of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s11414-014-9397-8. doi:10.1007/s11414-014-9397-8* [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmuss D, Fennelly K. Barriers to prenatal care among low-income women in New York City. Family Planning Perspectives. 1990;22(5):215–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes MA, Wittchen H, Kendler K. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51(1):8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, Edlund MJ, Frank RG, Leaf PJ. The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: Implications for prevention and service utilization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1996;66(1):17–31. doi: 10.1037/h0080151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerwin ME, Walker-Smith K, Kirby KC. Comparative analysis of state requirements for the training of substance abuse and mental health counselors. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;30(3):173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.11.004. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2005.11.004* [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine; Washington, DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kola LA, Kruszynski R. Adapting the Integrated Dual-Disorder Treatment Model for Addiction Services. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2010;28(4):437–450. [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn BM. Integrated care key for patients with both addiction and mental illness. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303(19):1905–1907. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.597. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.597* [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby AM, Riggs PD. Integrated substance use and mental health treatment for adolescents: Aligning organizational and financial incentives. Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2005;15(5):826–834. doi: 10.1089/cap.2005.15.826. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby AM, Orton HD, Barth RP, Webb MB, Burns BJ, Wood PA, Spicer P. Mental health and substance abuse services to parents of children involved with child welfare: A study of racial and ethnic differences for American Indian parents. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2007;34(2):150–159. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0099-2. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10488-006-0099-2* [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little J. Treatment of dually diagnosed clients. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2001;33(1):27–31. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2001.10400465. doi:10.1080/02791072.2001.10400465* [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern MP, Lambert-Harris C, Acquilano S, Xie H, Alterman AI, Weiss RD. A cognitive behavioral therapy for co-occurring substance use and posttraumatic stress disorders. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34(10):892–897. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mericle A. Identifying need for mental health services in substance abuse clients. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2012;8(3):218. doi:10.1080/15504263.2012.696182* [Google Scholar]

- Miles Matthew B., Huberman A. Michael. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Minkoff K. Best practices: Developing standards of care for individuals with cooccurring psychiatric and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2014;52(5):597–599. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.5.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millman M, editor. Access to health care in America. National Academy Press; Washington, D.C.: 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Chen LY, Kaufmann CN, Crum RM. Comparing barriers to mental health treatment and substance use disorder treatment among individuals with comorbid major depression and substance use disorders. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2014;46(2):268–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Drake RE, Wallach MA. Dual diagnosis: A review of etiological theories. Addictive Behaviors. 1998;23(6):717–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowotny KM. Race/ethnic disparities in the utilization of treatment for drug dependent inmates in U.S. State correctional facilities. Addictive Behaviors. 2015;40:148–153. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.09.005. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.09.005* [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act U.S.C. 2010;42:§ 18001. [Google Scholar]

- Penn PE, Brooks AJ, Worsham B. Treatment concerns of women with cooccurring serious mental illness and substance abuse disorders. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2002;34(4):355–362. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2002.10399976. doi:10.1080/02791072.2002.10399976* [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pincus H, Page A, Druss B, Appelbaum P, Gottlieb G, England M. Can psychiatry cross the quality chasm? Improving the quality of health care for mental and substance use conditions. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164(5):712–719. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.5.712. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, Goodwin FK. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1990;264(19):2511–2518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ro MJ, Casares C, Treadwell HM, Braithwaite K. Access to mental health care and substance abuse treatment for men of color in the U.S.: Findings from the national healthcare disparities report. Challenge: A Journal of Research on African American Men. 2006;12(2):65–74. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/61676525?accountid=14605* [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Locke BZ, Regier DA. An overview of psychiatric disorders in America. In: Robins LN, Regier DA, editors. Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Free Press; New York: 1991. pp. 328–366. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen D, Tolman R, Warner L. Low-income women's use of substance abuse and mental health services. Journal of Health Care for the Poor & Underserved. 2004;15(2):206–219. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2004.0028. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush B, Koegl CJ. Prevalence and profile of people with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders within a comprehensive mental health system. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie. 2008;53(12):810–821. doi: 10.1177/070674370805301207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks S, Banks S, McKendrick K, Sacks JY. Modified therapeutic community for co-occurring disorders: A summary of four studies. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;34(1):112–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks S, McKendrick K, Sacks JY, Cleland CM. Modified therapeutic community for co-occurring disorders: single investigator meta analysis. Substance Abuse. 2010;31(3):146–161. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2010.495662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seay KD, Kohl PL. The comorbid and individual impacts of maternal depression and substance dependence on parenting and child behavior problems. Journal of Family Violence. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10896-015-9721-y. doi: 10.1007/s10896-015-9721-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, Unützer J. Health care utilization and costs among patients treated for bipolar disorder in an insured population. Psychiatric services. 1999;50(10):1303–1308. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.10.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slayter EM. Disparities in access to substance abuse treatment among people with intellectual disabilities and serious mental illness. Health & Social Work. 2010;35(1):49. doi: 10.1093/hsw/35.1.49. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smelson D. Preliminary outcomes from a community linkage intervention for individuals with co-occurring substance abuse and serious mental illness. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2005;1(3):47. doi:10.1300/J374v04n03-05* [Google Scholar]

- Smelson D, Kalman D, Losonczy M, Kline A, Sambamoorthi U, Hill L, Ziedonis D. A brief treatment engagement intervention for individuals with co-occurring mental illness and substance use disorders: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Community Mental Health Journal. 2012;48(2):127–132. doi: 10.1007/s10597-010-9346-9. doi:10.1007/s10597-010-9346-9* [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling S, Weisner C, Hinman A, Parthasarathy S. Access to treatment for adolescents with substance use and co-occurring disorders: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49(7):637–646. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.03.019. * [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Association Report on co-occurring disorders recommends integrated treatment. SAMHSA News. 2002;10 [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration About co-occurring disorders. 2015 Feb 11; Retrieved from http://media.samhsa.gov/co-occurring/ [PubMed]

- Sumartojo E. Structural factors in HIV prevention: concepts, examples, and implications for research. AIDS. 2000;14:S3–S10. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawil O, Vester A, O'Reilly KR. Enabling approaches for HIV/AIDS prevention: Can we modify the environment and minimize the risk? AIDS. 1995;9(12):1299–1306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]