Abstract

Chronic Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection may cause kidney injury, particularly in the setting of cryoglobulinemia or cirrhosis; however, few studies have evaluated the epidemiology of acute kidney injury in patients with HCV. We aimed to describe national temporal trends of incidence and impact of severe AKI requiring renal replacement (“dialysis-requiring AKI”) in hospitalized adults with HCV. We extracted our study cohort from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project using data from 2004–2012. We defined HCV and dialysis-requiring acute kidney injury based on previously validated ICD-9-CM codes. We analyzed temporal changes in the proportion of hospitalizations complicated by dialysis-requiring AKI and utilized survey multivariable logistic regression models to estimate its impact on in-hospital mortality. We identified a total of 4,603,718 adult hospitalizations with an associated diagnosis of HCV from 2004–2012, of which 51,434 (1.12%) were complicated by dialysis-requiring acute kidney injury. The proportion of hospitalizations complicated by dialysis-requiring acute kidney injury increased significantly from 0.86% in 2004 to 1.28% in 2012. In-hospital mortality was significantly higher in hospitalizations complicated by dialysis-requiring acute kidney injury vs. those without (27.38% vs. 2.95%; adjusted odds ratio 2.09, 95% Confidence Interval 1.74–2.51). The proportion of HCV hospitalizations complicated by dialysis-requiring acute kidney injury increased significantly between 2004–2012. Similar to observations in the general population, dialysis-requiring acute kidney injury was associated with a two-fold increase in odds of in-hospital mortality in adults with HCV. These results highlight the burden of acute kidney injury in hospitalized adults with HCV infection.

Keywords: acute kidney injury, dialysis, mortality, hepatitis C

Chronic Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection affects an estimated 3.2 million Americans, is particularly prevalent in the “baby boomer” population, and places a huge burden on healthcare resources in the United States.(1) With the advent of newer therapies, sustained virologic response (SVR) is increasingly common. Although the results are confounded by baseline health status, studies suggest that HCV treatment has significantly improved life expectancy for HCV positive patients; however, the impact of successful treatment on extrahepatic complications is less clear. (2) Previous studies have suggested that HCV infection is associated with an increased risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in HIV-HCV co-infected patients and in United States (US) veterans, who have high rates of screening for HCV (3) Cohort studies of US veterans have demonstrated increased odds of prevalent and incident CKD and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) among HCV-positive compared to HCV-negative veterans.(4)

Classically, HCV infection predisposes to cryoglobulinemic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN), however HCV-positive individuals may also be at increased risk for kidney injury secondary to end-stage liver disease, injecting drug use, concomitant CKD, or HIV co-infection. (5) In addition, acute kidney injury (AKI) is a potential independent risk factor for incident and progressive CKD.(6,7) Data evaluating the incidence of AKI among HCV-positive individuals are limited, and most studies have focused on the HIV-HCV co-infected population. (8) To address this knowledge gap, we utilized a large, nationally representative database to estimate the incidence of severe AKI requiring renal replacement therapy (“dialysis-requiring AKI”) among hospitalized HCV-positive adults between 2004 and 2012, and to evaluate the association of dialysis-requiring AKI with in-hospital mortality.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We extracted our dataset from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. We selected the time period 2004–2012 based on complete data availability and adequate sample size for optimal modeling. We queried the database using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes 070.41; 070.44; 070.51; 070.54; 070.70 and 070.71 to identify individual hospitalizations with an associated diagnosis of HCV infection. These codes have been used to identify HCV infection in prior studies. [1, 10] We defined AKI by ICD-9-CM code 584.xx. The dialysis procedure was identified by presence of ICD-9-CM procedure code of 39.95 or diagnosis code of v45.11, v56.0 or v56.1. (9) To avoid misclassification of hospitalizations for chronic hemodialysis initiation, we excluded those with procedure codes for arteriovenous access creation or revision.(10) Similarly, we excluded hospitalizations with dialysis codes but no AKI code, assuming that patients were receiving dialysis for ESRD. This approach to the diagnosis of dialysis-requiring AKI has been used previously and has sensitivity of 90.4%, specificity of 93.8%, and positive and negative predictive value of 94.0% and 90.0%, respectively. (9)

We calculated the proportion of hospitalizations with a documented diagnosis of dialysis-requiring AKI for each year from 2004–2012. We extracted demographics, concurrent diagnoses, hospital-level characteristics (geographical region, size, and teaching status) and estimated comorbidity burden and mortality risk using the validated All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Group (APRDRG) mortality score.(11) Because of the potential limitations of ICD-9-CM codes for the diagnosis of HCV infection, particularly when based on an individual hospitalization, we also conducted a sensitivity analysis stratifying HCV diagnoses by cirrhosis status. Specific diagnoses previously associated with increased risk of AKI were identified by ICD-9-CM codes for CKD, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, HIV, liver cancer, sepsis, heart failure, cardiac catheterization, and mechanical ventilation. We calculated adjusted odds ratios (aOR) for the association between these conditions and dialysis-requiring AKI.

To explore reasons for temporal changes in incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI, we constructed three sequential logistic regression models (Model 1: Calendar year; Model 2: Year + temporal changes in demographics; Model 3: Year + changes in demographics + changes in diagnoses/procedure).

We utilized survey multivariable logistic regression models to estimate impact of dialysis-requiring AKI on hospital mortality. We utilized SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, North Carolina) for all analyses and included designated weight values to produce nationally representative estimates. We considered a two-tailed p value ≤ 0.05 as statistically significant.

RESULTS

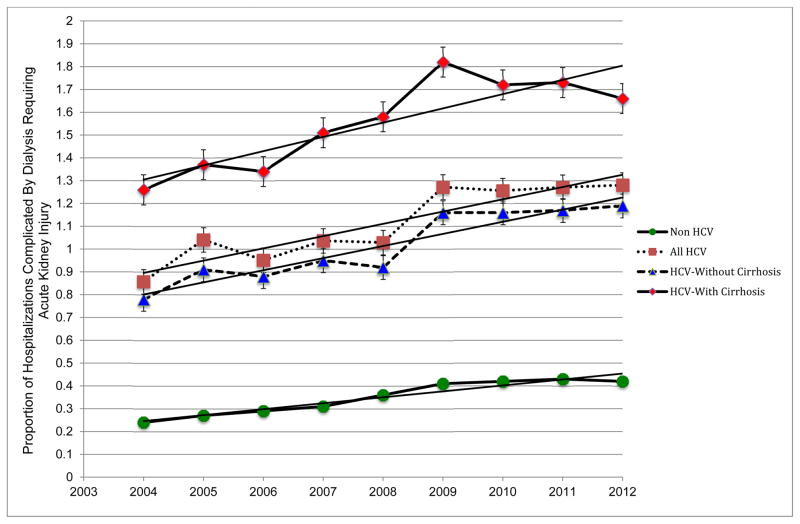

We identified 4,603,718 adult hospitalizations with an associated HCV diagnosis from 2004–2012. Dialysis-requiring AKI was documented as a complication in 51,434 (1.12%) of these hospitalizations. The proportion of hospitalizations complicated by dialysis-requiring AKI increased significantly between 2004 and 2012 [3462/403,874 (0.86%) in 2004 versus 7750/605,161 (1.28%) in 2012]; however, this proportion was stable between 2009–2012 despite an increase in the absolute number of cases (Figure 1). In sensitivity analysis, these trends were similar when stratified by cirrhosis status. For qualitative comparison, similar data are shown for adult hospitalizations without an associated diagnosis of HCV.

Figure 1.

Temporal Trends in the Incidence of Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) Requiring Renal Replacement Therapy among Hospitalized Adults with and without Documented Hepatitis C Virus Infection

Patient characteristics significantly associated with dialysis-requiring AKI (p<0.001) included older age (54.7 vs. 43.5 years in those without AKI); male gender (71.2% vs. 63.8%); African American race (59.5% vs. 51.5%); higher APRDRG risk of mortality score (3.4 vs. 2.3); and chronic comorbidities including diabetes (33.35% vs. 25.47%), hypertension (59.11% vs. 43.05%), chronic liver disease (51.73% vs. 29.63%), liver cancer (5.02% vs. 3.52%); and CKD (19.32% vs. 6.27%). Hospitalizations complicated by dialysis-requiring AKI were more likely to be complicated by other acute conditions including acute myocardial infarction (5.23% vs. 1.41%), heart failure (3.51% vs. 2.09%), sepsis (36.68% vs. 6.75%) and procedures including mechanical ventilation (34.69% vs. 4.46%) and cardiac catheterizations (3.03% vs. 2.2%). (Table 1) The strongest predictors of dialysis-requiring AKI included mechanical ventilation (adjusted odds ratio, aOR of 6.14); sepsis (aOR of 3.95); CKD (aOR of 2.17); chronic liver disease (aOR of 2.1); and heart failure (aOR of 1.79). (Table 2)

Table 1.

Characteristics of hospitalized HCV-positive adults with and without dialysis-requiring acute kidney injury, 2004–2012

| HCV patients without dialysis requiring acute kidney injury (n=4,552,284) | HCV patients with dialysis requiring acute kidney injury (n=51,434) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean (SE) | 51.5 (0.12) | 54.7 (0.14) | <0.001 |

| 0–19 | 0.23 | 0.08 | <0.001 |

| 20–44 | 22.66 | 12.81 | |

| 45–64 | 66.56 | 72.9 | |

| ≥65 | 10.54 | 14.21 | |

| Gender % | <0.001 | ||

| Male | 62.13 | 68.4 | |

| Female | 37.85 | 31.6 | |

| Race % | <0.001 | ||

| White | 50.78 | 41.15 | |

| Black | 19.81 | 28.33 | |

| Hispanic | 11.26 | 14.43 | |

| Others | 4.56 | 5.87 | |

| Missing | 13.59 | 10.22 | |

| APRDRG Mortality Scale % | <0.001 | ||

| Mean (SE) | 3.4 (0.05) | 2.3 (0.03) | |

| 0 | 44.58 | 0.5 | |

| 1 | 30.38 | 15.3 | |

| 2 | 18.42 | 28.15 | |

| 3 | 6.56 | 56.05 | |

| Concurrent Diagnosis % | |||

| Diabetes Mellitus | 25.47 | 33.35 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 43.05 | 59.11 | <0.001 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease* | 6.27 | 19.32 | <0.001 |

| HIV | 8.46 | 8.53 | 0.59 |

| Chronic Liver Disease | 29.63 | 51.73 | <0.001 |

| Liver or intrahepatic billiary Cancer | 3.52 | 5.02 | <0.001 |

| Sepsis | 6.75 | 36.68 | <0.001 |

| Acute Myocardial Infarction | 1.41 | 5.23 | <0.001 |

| Acute Heart Failure | 2.09 | 3.51 | <0.01 |

| Cardiac catheterizations | 2.27 | 3.03 | 0.05 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 4.46 | 34.69 | <0.001 |

Table 2.

Adjusted Odds Ratios of Comorbidities significantly associated with developing dAKI in documented HCV hospitalizations

| Comorbidity | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Ventilation | 6.141 (5.68–6.64) | <0.001] |

| Sepsis | 3.95 (3.75–4.17) | <0.001] |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 2.17 (2.03–2.33) | <0.001] |

| Chronic Liver Disease | 2.11 (1.97–2.26) | <0.001] |

| Heart Failure | 1.79 (1.66–1.93) | <0.001] |

| Hypertension | 1.78(1.67–1.90) | <0.001] |

| Diabetes | 1.10 (1.05–1.16) | <0.001] |

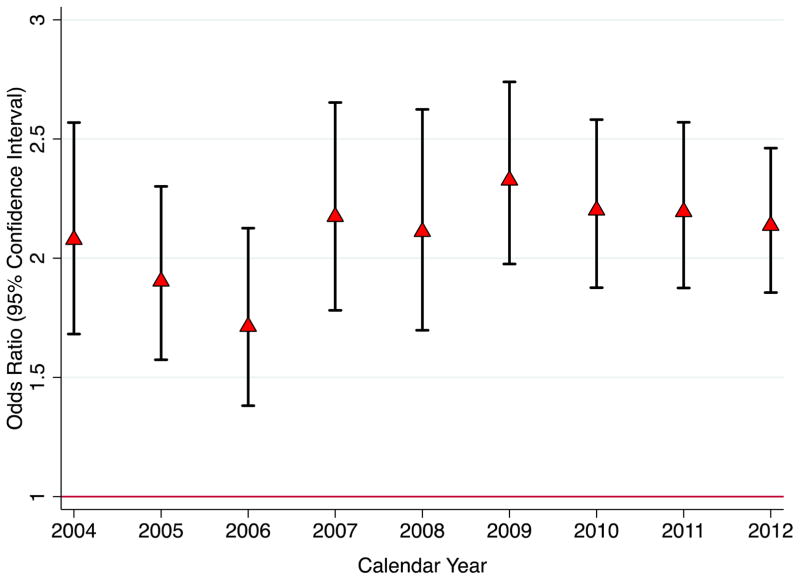

In-hospital mortality was significantly higher in hospitalizations complicated by dialysis-requiring AKI vs. those without (27.38% vs. 2.85%; p<0.001). After adjusting for demographics, APRDRG risk of mortality score, acute and chronic comorbidities, and hospital level factors, the overall adjusted odds ratio was 2.09 (95% Confidence Interval 1.74–2.51; p<0.001). The increase in in-hospital mortality associated with dialysis-requiring AKI was relatively stable over the study period. (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Adjusted Odds of In-Hospital Mortality Associated with Dialysis-requiring Acute Kidney Injury in Hospitalized Adults with HCV infection

For qualitative purposes, we also explored the comparison with trends in the general population. As demonstrated in Figure 1, the incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI among hospitalized adults was notably higher in the setting of HCV infection (p<0.001). In unadjusted comparison of demographic and clinical characteristics between HCV-positive and HCV-negative adults with dialysis-requiring AKI, HCV positive patients were younger, more likely to be African American and to have a higher comorbidity score. They had lower proportions of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, CKD, acute myocardial infarction and heart failure, but higher proportions of HIV co-infection, chronic liver disease, liver cancer, sepsis and mechanical ventilation. (Table 3) Given the significant differences in comorbidities and indications for hospitalization, we felt that further comparative analysis was beyond the scope of the current study.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Hospitalizations Complicated by Dialysis Requiring Acute Kidney Injury, Stratified by Documented Hepatitis C Infection Status, 2004–2012

| Non-HCV patients with dialysis-requiring AKI (n=1,333,936) | HCV-positive patients with dialysis-requiring AKI (n=51,434) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age Mean (SE) | 63.68(0.15) | 54.77(0.14) | <0.001 |

| 0–19 | 1.06 | 0.08 | |

| 20–44 | 11.83 | 12.79 | |

| 45–64 | 33.78 | 72.82 | |

| ≥65 | 53.31 | 14.31 | |

| Gender | <0.001 | ||

| Male | 56.7 | 68.42 | |

| Female | 43.29 | 31.58 | |

| Race | <0.001 | ||

| White | 52.67 | 41.14 | |

| Black | 16.63 | 28.33 | |

| Hispanic | 9.73 | 14.35 | |

| Others | 5.67 | 5.91 | |

| Missing | 15.3 | 10.26 | |

| APRDRG Mortality Scale | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 0.45 | 0.49 | |

| 1 | 15.37 | 15.29 | |

| 2 | 30.53 | 28.2 | |

| 3 | 53.64 | 56.01 | |

| Concurrent Diagnosis | |||

| Diabetes Mellitus | 39.92 | 33.33 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 69.66 | 59.07 | <0.001 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 22.93 | 19.3 | <0.001 |

| HIV | 1.42 | 8.54 | <0.001 |

| Acute or Chronic Liver Disease | 16.45 | 51.59 | <0.001 |

| Liver or intrahepatic billiary | |||

| Cancer | 0.36 | 4.99 | <0.001 |

| Sepsis | 33.15 | 36.67 | <0.001 |

| Acute Myocardial Infarction | 9.76 | 5.23 | <0.001 |

| Primary Acute Heart Failure | 6.14 | 3.48 | |

| Cardiac catheterizations | 5.3 | 3.01 | |

| Mechanical ventilation | 30.85 | 34.64 |

In order to explain the observed temporal increase in incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI, we constructed a univariable model including only year. This model demonstrated that the odds of dialysis-requiring AKI increased annually by 5% (OR 1.05; 95% CI 1.03–1.07) between 2004 and 2012. Adjustment for patient demographics had minimal effect (adjusted OR 1.03; 95% CI 1.02–1.05.). After adjustment for changes in demographics and concurrent diagnoses (sepsis, myocardial infarction, heart failure, diabetes, hypertension, CKD, cirrhosis, and liver cancer) and procedures (cardiac catheterizations and mechanical ventilation) previously associated with AKI, the impact of year was completely attenuated (adjusted OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.97–1.003; p=0.49).

DISCUSSION

In a large, nationally representative sample of hospital admissions, we found a rising incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI among hospitalized HCV-positive adults between 2004–2012. The rising incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI was largely explained by temporal changes in acute and chronic comorbidities and concurrent procedures. This is consistent with reports in the general population, including a recent study demonstrating a yearly increase of 10% in the population level incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI.(12)

We could account for the increasing incidence in dialysis-requiring AKI with temporal changes in demographics, comorbidities, and procedures. Although we cannot exclude more liberal use of acute dialysis over time,(13) in the general population both dialysis-requiring and laboratory-defined AKI have been increasing in incidence.(14) Dialysis-requiring AKI was also associated with a significant increase in in-hospital mortality, consistent with studies in the general population.(12)

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to use a nationally representative database to analyze temporal trends of dialysis-requiring AKI among hospitalized HCV-positive adults. The use of a nationally representative sample allowed for excellent power and generalizability. We also recognize several limitations, the foremost being the use of administrative data to define HCV infection. The majority of previous studies of HCV and kidney disease outcomes have defined HCV based on antibody status, and studies evaluating the independent effect of HCV viremia have yielded conflicting results.(15,16) Nonetheless, the sensitivity of ICD-9-CM codes for the diagnosis of HCV infection has not been well established. Although a study in the US Veterans Affairs Health System demonstrated reasonable positive and negative predictive value to identify patients with a known diagnosis of HCV infection, that study included both inpatient and outpatient data from the longitudinal patient record.(17) Because our definition of HCV infection was based on a single inpatient record, it is likely that some persons with a known diagnosis of HCV infection that was not relevant to the acute illness were misclassified and thus excluded from our primary analysis. In sensitivity analysis, temporal trends were similar in patients with HCV infection and a documented diagnosis of cirrhosis. In addition, while dialysis-requiring AKI codes have been found to have excellent validity (9), we could not discriminate between continuous versus intermittent renal replacement therapy and de novo AKI versus acute-on-chronic kidney disease, and we could not determine the duration of acute dialysis. Because data were de-identified, we could not identify individuals with multiple hospitalizations or recurrent episodes of dialysis-requiring AKI.

In summary, we observed a significant increase in incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI among hospitalized HCV-positive adults between 2004–2012. This was largely explained by temporal changes in acute illness severity and prevalence of chronic comorbidities known to be associated with AKI. As in the general population, dialysis-requiring AKI was associated with a significant increase in inhospital mortality among HCV-positive adults. Future studies should consider the impact of oral antiviral therapy on the epidemiology of AKI and CKD in this population.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This work was supported in part by funding from the National Institutes of Health to GNN (T32DK00775716).

Footnotes

Disclosures: All authors report no conflict of interest

References

- 1.Galbraith JW, Donnelly JP, Franco RA, Overton ET, Rodgers JB, Wang HE. National estimates of healthcare utilization by individuals with hepatitis C virus infection in the United States. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2014 Sep 15;59(6):755–64. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van der Meer AJ, Wedemeyer H, Feld JJ, Dufour J-F, Zeuzem S, Hansen BE, et al. Life expectancy in patients with chronic HCV infection and cirrhosis compared with a general population. JAMA. 2014 Nov 12;312(18):1927–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.12627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peters L, Grint D, Lundgren JD, Rockstroh JK, Soriano V, Reiss P, et al. Hepatitis C virus viremia increases the incidence of chronic kidney disease in HIV-infected patients. AIDS Lond Engl. 2012 Sep 24;26(15):1917–26. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283574e71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dalrymple LS, Koepsell T, Sampson J, Louie T, Dominitz JA, Young B, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection and the prevalence of renal insufficiency. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol CJASN. 2007 Jul;2(4):715–21. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00470107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garg S, Hoenig M, Edwards EM, Bliss C, Heeren T, Tumilty S, et al. Incidence and predictors of acute kidney injury in an urban cohort of subjects with HIV and hepatitis C virus coinfection. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2011 Mar;25(3):135–41. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coca SG, Singanamala S, Parikh CR. Chronic kidney disease after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Int. 2012 Mar;81(5):442–8. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chawla LS, Eggers PW, Star RA, Kimmel PL. Acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease as interconnected syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2014 Jul 3;371(1):58–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1214243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franceschini N, Napravnik S, Finn WF, Szczech LA, Eron JJ. Immunosuppression, hepatitis C infection, and acute renal failure in HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2006 Jul;42(3):368–72. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000220165.79736.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waikar SS, Wald R, Chertow GM, Curhan GC, Winkelmayer WC, Liangos O, et al. Validity of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification Codes for Acute Renal Failure. J Am Soc Nephrol JASN. 2006 Jun;17(6):1688–94. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsu RK, McCulloch CE, Dudley RA, Lo LJ, Hsu C. Temporal changes in incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol JASN. 2013 Jan;24(1):37–42. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012080800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baram D, Daroowalla F, Garcia R, Zhang G, Chen JJ, Healy E, et al. Use of the All Patient Refined-Diagnosis Related Group (APR-DRG) Risk of Mortality Score as a Severity Adjustor in the Medical ICU. Clin Med Circ Respir Pulm Med. 2008;2:19–25. doi: 10.4137/ccrpm.s544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu RK, McCulloch CE, Dudley RA, Lo LJ, Hsu C. Temporal changes in incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol JASN. 2013 Jan;24(1):37–42. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012080800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siew ED, Davenport A. The growth of acute kidney injury: a rising tide or just closer attention to detail? Kidney Int. 2015 Jan;87(1):46–61. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsu C-Y, McCulloch CE, Fan D, Ordoñez JD, Chertow GM, Go AS. Community-based incidence of acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 2007 Jul;72(2):208–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mocroft A, Neuhaus J, Peters L, Ryom L, Bickel M, Grint D, et al. Hepatitis B and C co-infection are independent predictors of progressive kidney disease in HIV-positive, antiretroviral-treated adults. PloS One. 2012;7(7):e40245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lucas GM, Jing Y, Sulkowski M, Abraham AG, Estrella MM, Atta MG, et al. Hepatitis C viremia and the risk of chronic kidney disease in HIV-infected individuals. J Infect Dis. 2013 Oct 15;208(8):1240–9. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kramer JR, Davila JA, Miller ED, Richardson P, Giordano TP, El-Serag HB. The validity of viral hepatitis and chronic liver disease diagnoses in Veterans Affairs administrative databases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008 Feb 1;27(3):274–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]