Abstract

Background

The Affordable Care Act encourages healthcare systems to integrate behavioral and medical healthcare, as well as to employ electronic health records (EHRs) for health information exchange and quality improvement. Pragmatic research paradigms that employ EHRs in research are needed to produce clinical evidence in real-world medical settings for informing learning healthcare systems. Adults with comorbid diabetes and substance use disorders (SUDs) tend to use costly inpatient treatments; however, there is a lack of empirical data on implementing behavioral healthcare to reduce health risk in adults with high-risk diabetes. Given the complexity of high-risk patients' medical problems and the cost of conducting randomized trials, a feasibility project is warranted to guide practical study designs.

Methods

We describe the study design, which explores the feasibility of implementing substance use Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) among adults with high-risk type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) within a home-based primary care setting. Our study includes the development of an integrated EHR datamart to identify eligible patients and collect diabetes healthcare data, and the use of a geographic health information system to understand the social context in patients' communities. Analysis will examine recruitment, proportion of patients receiving brief intervention and/or referrals, substance use, SUD treatment use, diabetes outcomes, and retention.

Discussion

By capitalizing on an existing T2DM project that uses home-based primary care, our study results will provide timely clinical information to inform the designs and implementation of future SBIRT studies among adults with multiple medical conditions.

Keywords: Diabetes, home-based primary care, medical comorbidity, referral to treatment, substance use disorder, substance use screening

1. Introduction

The Affordable Care Act encourages healthcare systems to integrate behavioral and medical healthcare and use electronic health records (EHRs) for health information exchange and quality improvement [1,2]. Developing integrated systems in primary care to facilitate management of substance use disorders (SUDs: tobacco, alcohol, or drug) by using the EHR to streamline the workflow for substance use Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) has become a priority [2,3]. SBIRT provides an office-based framework that may enhance the identification of patients with substance misuse or SUD and facilitate treatment and coordinated care [4,5]. In line with the Triple-Aim reform, the United States (U.S.) is shifting away from fee-for-service medical care to a value-based model that seeks not only to improve healthcare and outcomes, but to lower costs [6,7]. A value-based care system emphasizes the need to effectively identify people with multiple comorbidities in order to engage them in a coordinated chronic care model for outcomes improvement [7–9]. For example, the most costly 10% of the U.S. patient population (e.g., adults with multiple chronic diagnoses such as diabetes, SUD) account for 66% of total care expenditures [10]. Early detection of high-risk patients is necessary to implement targeted interventions that will reduce avoidable hospitalizations and lower costs [9,10]. In keeping with the value-based purchasing, home-based primary care is considered by Institute of Medicine to be a promising care delivery model with long-term cost-savings for those with complex health needs [7].

Diabetes is a leading cause of death and a commonly encountered chronic disease in primary care [11,12]. As many as one in three U.S. adults will have diabetes by 2050 [13]. About 90–95% of individuals with diabetes have T2DM [14]. Diabetes is associated with severe, but preventable, complications (e.g., limb amputations). Individuals with diagnosed diabetes have medical expenditures estimated to be 2.3 times higher than those without diabetes [15]. Approximately 20% of adults with diabetes are current cigarette smokers, and 50–60% are current alcohol users [16]. Cigarette smoking, binge/heavy alcohol use, and alcohol/drug use disorder interfere with diabetes self-care or increase diabetes complications [17–20]. Diabetes complications and SUDs are among the leading contributors to hospital admissions [21,22]. Therefore, integrated care for diabetes and SUDs is critically needed to minimize health risk. SBIRT should address all categories of SUDs.

There is a lack of data to inform implementation of SBIRT for adults with T2DM. Recent data suggest that “brief intervention” is ineffective among adult patients with severe drug use problems who have high rates of poverty and/or psychiatric comorbidity [23,24]. Hence, an SBIRT framework should take into account patients' substance use risk level and incorporate referral to treatment to facilitate linkage to SUD treatment. To inform the design of larger studies of an integrated home-based practice model [7], we describe a prospective design to assess the feasibility of implementing SBIRT among patients with high-risk T2DM. This design considers substance use levels, includes referral to SUD treatment, and leverages EHR in recruitment and data collection to inform healthcare utilization.

2. Methods

2.1. Study aims

This National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network (CTN) study assesses the feasibility of implementing SBIRT in patients with high-risk T2DM within a home-based practice model, describes the substance use status of participating patients over time, and explores associations between substance use and healthcare utilization.

2.2. Study area and setting

The diabetes epidemic is growing in North Carolina. In 1999, an estimated 366,000 residents were living with diagnosed diabetes; ten years later, the prevalence of diagnosed cases had increased to approximately 659,000 [25]. North Carolina is one of southern states with the highest prevalence (11.7%) of diagnosed diabetes in the nation [26,27]. Compared with the overall U.S. population, Durham County has a much higher proportion of Black/African American residents (13.2% vs. 38.7%) [28]. Compared with Whites, Blacks/African Americans have a higher prevalence of T2DM, poor quality of care, and diabetes related complications and disability [29]. A multifactorial, community-based approach has been recommended to improve patient outcomes via targeting multiple diabetic risk factors [29]. We analyzed the EHR data from over 170,000 adults aged ≥18 years in Durham County who received care at one or more of the Duke University Health System clinics during 2007–2011. We found that 17% of patients with T2DM had an alcohol, tobacco, or drug use diagnosis documented in their EHR compared with 8% of patients without T2DM [30]. Because SUDs have not been systematically evaluated, the actual prevalence of SUD may be higher than the documented prevalence.

The Duke University Health System serves as Durham County's primary hospital and emergency medicine system. The Durham Diabetes Coalition (DDC) is part of the Southeastern Diabetes Initiative (SEDI; Duke University IRB Pro00043463 funded by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation). The DDC was established in response to the escalating prevalence of disability and death related to T2DM, particularly among racial/ethnic minorities and adults of low socioeconomic status in Durham County [31]. The DDC is a joint effort of Duke University and external partners (e.g., Durham County Department of Public Health, CAARE, Lincoln Community Health Center). SEDI augments the existing standard of care in an effort to improve population-level diabetes management, reduce disparities in management and outcomes in underserved communities, and lower healthcare costs for adults living with T2DM. To contain study costs, our SBIRT study uses the existing SEDI infrastructure to recruit patients who are SEDI participants in Durham County.

2.3. Study designs

Our current study uses a prospective design, nested within the larger SEDI study, to explore the feasibility of implementing SBIRT among adults with high-risk T2DM. We have employed the SEDI clinical team to implement SBIRT in order to reduce costs and examine the feasibility of conducting SBIRT in a real-world setting. Using EHR data, we identify eligible patients for recruitment and prospectively track diabetes care (medication adherence), health related quality of life, and healthcare utilization (e.g., SUD treatment, emergency department or inpatient hospitalization admissions). Our goal is not to test the efficacy or effectiveness of SBIRT, but to generate empirical data that will inform the design, conduct, and implementation of EHR-enabled SBIRT among diabetes patients with multiple comorbidities within a chronic care model [16,32]. Randomization and blinding are not part of the study design.

Specifically, due to a lack of substance use prevalence data in the adult population with high-risk T2DM, we collect substance use prevalence and severity data to guide the planning of future trials. We collect recruitment, follow-up rates, as well as receipt of Brief Intervention (BI) and Referral to Treatment (RT) to understand the feasibility of implementing SBIRT and to inform power analysis for randomized trials. Additionally, we assess the diabetic medication adherence prevalence, health related quality of life, emergency department encounters, inpatient admissions, and diabetes related medical complications to explore their associations with substance use. The latter information about substance use and diabetes related healthcare utilization is relevant to informing the potential effect of SBIRT on clinical practices and the designs of pragmatic randomized trials.

2.4. SEDI inclusion and exclusion criteria

Our study includes eligible patients with T2DM who are screened for and identified as high-risk adults (described below) enrolled in the SEDI home-based clinical intervention in Durham County, North Carolina [31].

2.4.1. Inclusion criteria

To be included in the study, one must: 1) be ≥18 years; 2) have a diagnosis of T2DM as defined by one or more of the following: prior diagnosis as designated by a clinician, glucose ≥126 mg/dl at fasting and ≥200 mg/dl on random sample, or a glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥6.5%; 3) be a resident of Durham County, North Carolina or the neighboring areas, and receive the majority of their healthcare in Durham County; 4) have the capacity to give informed consent; 5) be defined as high risk by the risk algorithm (detailed below); and 5) be referred from the primary care clinician or patient's medical home.

2.4.2. Exclusion criteria

To be excluded from the study, one must: 1) lack the capacity to make healthcare decisions and have no surrogate with the authority to make these decisions for them; 2) have a terminal illness with a life expectancy of 6 months or less; 3) have a diagnosis of type 1 or gestational diabetes; 4) be pregnant; or 4) be unwilling to comply with study requirements. Because the screening and assessment tool for SBIRT is only available in English, non-English speaking adults are also excluded from the study. We will use the results from this study to guide the study design for non-English speakers.

2.5. EHR data-drive approach to informing risk-stratified intervention

To inform targeted interventions and improve health outcomes for patients with diabetes in Durham County, a mathematical risk algorithm was created using the EHR data from Duke University Health System, including demographic, diagnoses, lab, and medication data, was developed to assign adults with T2DM a risk score to place them into low, moderate and high risk groups so that appropriate interventions can be applied [31]. Specifically, a logistic regression equation was developed using existing clinical data to predict risk for serious outcomes, defined as hospital/emergency department admission or death. The initial algorithm predicted poor outcomes in calendar year 2011 based on 2010 EHR data, and then validated the model prediction using 2012 EHR data. Candidate variables were selected from proven risk factors for poor outcomes in patients with diabetes reported in the literature and suggested by expert clinician input [31].

2.5.1. An integrated EHR datamart

SEDI recruits patients either through direct referrals from providers affiliated with the Duke University Health System or from screening the Duke EHR system (with provider permission) to contact patients. Potentially eligible patients are identified from the Duke EHR system and referrals from providers affiliated with Duke University Health System clinics. The primary source of EHR is the Duke Enterprise Data Warehouse [33], which integrates EHR containing clinical data (e.g., laboratory, diagnostic, clinical notes, tests, etc.) from clinical encounters across the health system, including more than 25 major clinical systems.

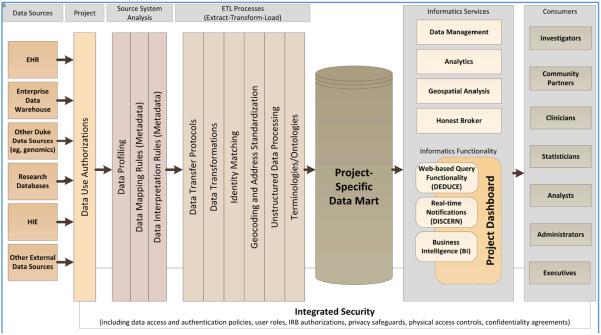

SEDI uses an EHR data-driven approach to informing risk-stratified intervention. SEDI includes clinical sites located in four counties across the southeastern United States: Cabarrus County, NC; Durham County, NC; Mingo County, WV; and Quitman County, MS. To allow data sharing for research analysis and progress reporting across data sharing partners, an informatics team at Duke University has developed an integrated EHR datamart. The conceptual model for this informatics- and research-driven datamart is shown in Fig. 1 [34,35]. This datamart is designed to accommodate project-specific research objectives and scope by following a consistent set of practices, and integrated security is a foundation for all systems and processes. The development includes a series of processes or components [34,35]: data sources (e.g., Both internal and external data sources can be utilized independently for any given project.); project authorizations (Contracting, authorizations, and data use agreements are dependent on the context of each data source.); source system analysis (A methodical analysis of data and systems architecture is applied for each individual data source with best practices of profiling and metadata development.); extract-transform-load processes (These procedures programmatically mediate data transfers, data transformations, identity matching, address standardization and geocoding, and unstructured data.); project-specific datamart (Each datamart is intended to be system agnostic to take advantage of rapidly-evolving platforms, and it allows more agile adoption on an individual project basis than a more centralized system would require.); informatics services and functionality (A catalog of services is incorporated to meet each project's objectives and scope.); existing platforms (EHR-based platforms provide a robust framework of functionality that can be deployed as appropriate.); consumers (The model is intended to meet the needs of project consumers with different roles and responsibilities.); and integrated security (Security and patient confidentiality are an integral part of all systems and maintained through complimentary mechanisms and policies.).

Figure 1.

A Conceptual Model for an Informatics-Driven Electronic Health Records Datamart

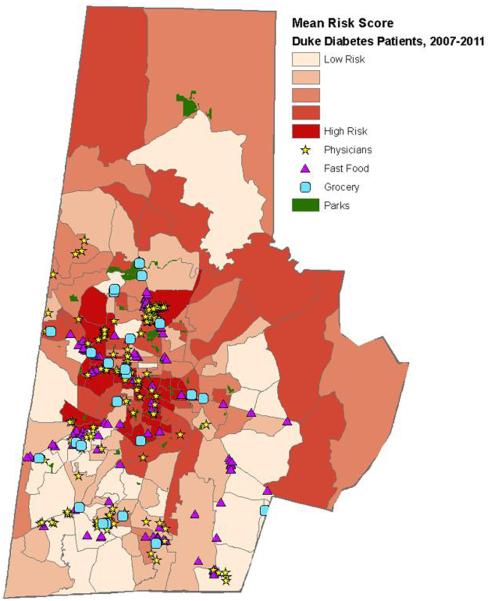

This standardized EHR datamart permits regular data harvests from multiple sources (EHR and non-EHR data sources), supports cross-site data analysis, and facilitates the integration of patients' EHR data with the census community-level information and patient-reported survey data in the data analysis. For example, by combining a regular EHR data extract with the risk algorithm, adults with T2DM can be assigned a composite risk score that places them on the intervention spectrum—from relatively low-risk, low-intensity, community-based interventions to relatively high-risk, high-intensity, home-based interventions [31]. To inform healthcare delivery and resource allocation for Durham County residents with T2DM (e.g., pinpointing the location of the neighborhood and community resources, linking patients with resources convenient for them to access), geographic information from the EHR is geocoded and linked with the census block group-level information to provide a multidimensional understanding of environmental contexts and vulnerabilities for adults living with T2DM in Durham and to develop tailored community-based interventions. This geographic health information system (GHIS) approach integrates clinical, social, and environmental data to provide tailored interventions that take into account a patient's neighborhood and population-level factors [36]. Fig. 2 shows an example of patient risk and community resource map [37]. Patient data was mapped and geographically linked with key social and environmental factors to determine the high-risk neighborhoods for the neighborhood interventions.

Figure 2.

An Example of Patient Risk Score and Community Resource Map

2.5.2. SBIRT recruitment

The SBIRT study includes high-risk T2DM participants (risk score within the top 10%) residing in Durham County targeted for enrollment in SEDI. Potential SEDI participants who express an interest in participating in the SBIRT study go through the informed consent process at the time they are consented for the SEDI study. They are then scheduled for a home visit by trained research staff (social workers) to conduct the SBIRT intake assessment. The SEDI clinical intervention also targets those who have experienced barriers to effective management of diabetes or roadblocks in accessing traditional office-based primary care (e.g., comorbidities, transportation barriers, lack of caregiver support). This high-risk group receives home-based primary care delivered by a multidisciplinary team (nurse practitioner, social worker, dietitian, and community health worker/patient navigator) over a period of up to 2 years; this home-based care is aimed at improving diabetic care and outcomes [38–40]. Diabetic adults with comorbid conditions have a high likelihood of frequently using inpatient or emergency care, and inadequate access to care can exacerbate medical problems [21,22]. Home-based primary care is considered in these high-risk patients, since this care model combines traditional clinical care for medical needs with team-based care management, self-care education, and care coordination. Home-based primary care may reduce unnecessary hospitalizations and enhance coordination of social support services and referrals to specialty clinics [38,39]. Consequently, the SBIRT intervention is conducted in the participants' home.

2.5.3. Sample size

Due to a lack of research data on engaging high-risk diabetes patients in SBIRT, our study is not powered to test the efficacy of SBIRT. Based on the projections for the SEDI clinical intervention, we plan to recruit 120 patients over 16 months. To compensate participants for their time, each participant is paid $25 for completing assessments at each scheduled visit (baseline, four follow-up visits). Each participant may receive up to $125 over the entire course of the study period.

2.6. Data collection

2.6.1. The assessment battery (Table 1)

Table 1.

| Smoking status | Alcohol use status | Nonmedical or illicit drug use status | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial single-item use screen | Do you currently smoke cigarettes? | In the past month, do you sometimes drink beer, wine, or other alcoholic beverages? | How many times in the past year have you used an illegal drug or used a prescription medication for “non-medical reasons?” [47] |

| Problem use assessment | Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) [44] | • Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) [45,46] • Drug type and frequency of use questions |

• Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10) [48,49] • Alcohol use disorder treatment status • Injection drug use • Drug use disorder treatment status |

Note: SUD treatment use information are obtained from the EHR. In addition, self-reported treatment use for alcohol and drug use disorder that are related to SBIRT are collected from surveys.

The assessment battery balances the need of brevity for screening substance use against the costs of data collection in terms of staff time, feasibility of completion in the primary care setting, and assessment reactivity. The size of the assessment battery is minimized to contain the cost and time of the study. The set of assessment for (nonmedical or illicit) drug use is based on the NIDA CTN's common data elements for SBIRT, including validated screening items and brief assessments to assess risk levels of substance use problems and intervention needs [41,42].

2.6.2. Definitions of SBIRT risk groups for intervention (Table 2)

Table 2.

| Risk group | Definition |

|---|---|

| The minimal risk S group | Non-users of cigarettes, alcohol, and drugs. |

| The at-risk SBI group | Current cigarette smokers, current alcohol users, or past-year drug users (having DAST-10 score 0–2 and all of the following: no daily use of any illicit and nonmedical drugs, no weekly use of illicit and nonmedical drugs, no injection drug use for nonmedical reasons in the past 3 months, not in SUD treatment) |

| The high-risk SBIRT group | High-risk drinkers (AUDIT-C score ≥5) [45,46] or high-risk drug users (having DAST-10 scores ≥3, or having DAST-10 scores 0–2 and any of the following: daily use of any illicit or nonmedical drugs, weekly use of illicit or nonmedical drugs, injection drug use for nonmedical reasons in the past 3 months, currently in SUD treatment). |

Brief, single questions allow rapid identification of substance use [47]. After a positive screening, a brief assessment is performed to stratify patients into three categories: minimal-risk, at-risk, and high-risk substance use [41,42]. Since all participants are high-risk patients with T2DM, identification of at-risk and high-risk groups is critical to improving care coordination, especially for individuals manifesting medical problems [4].

2.6.3. Portable computer-assisted assessment tool

An electronic data capture (EDC) system is used to create computer-assisted instruments. Due to the sensitive nature of substance use, the use of portable computer-assisted methodology is considered to facilitate ease of access to the tool and provide the participants with a private means of responding to substance use questions. To enhance participants' reporting of substance use, questions are displayed on a portable tablet screen, and the participant reads and enters responses directly into the EDC system using the tablet. The substance use screening assessment is conducted in a private setting. A touch screen tablet is used to make the technology more user-friendly. Participants indicate responses by simply touching the buttons on the screen.

Because high-risk patients with T2DM tend to be racial/ethnic minorities or adults of low socioeconomic status, we collect patients' literacy level and implement a contingency plan. All participants take the Rapid Estimates of Adult Literacy in Medicine Short-Form (REALM-SF) [50]. To accommodate the patient's literacy level and preference, the research staff may administer the assessment in a private setting and document electronically the interview mode and the patient's reason(s) for not self-administering it to inform future study designs.

The tablet wirelessly connects to the web to allow data entry into a secure, web-based portal of the EDC system. The research staff and the patient are required to log into the secure website with a username and password. A separate username and password are generated for the patient so that only the patient's record is visible. The patient can only enter data into the currently open time-point to prevent incorrect data entry. No data is stored on the portable tablets. Based on the response patterns defined by algorithms for the three intervention groups, the EDC generates responses in the system to indicate the patient's intervention status on the tablet (BI, RT, follow-up calls). This portable tool accommodates home-based primary care and produces point-of-care triggers for the designed staff to provide the intervention as indicated. Only designated research staff have access to the information.

2.6.4. The SBIRT training and monitoring

Two trained research staff conduct SBIRT and follow-up calls. Research staff complete two days of the SBIRT protocol and BI training (e.g., substance use and diabetes, substance use in the Durham/North Carolina area, SBIRT designs, substance use assessments, motivational interviewing approach, SUD treatment options, and referral resources). After completing the training, BI interventionists role-play with volunteers and then perform BI on at least two pilot patients with demonstrated fidelity evaluated by the BI trainer before conducting SBIRT. The lead physician of the clinical team serves as an ongoing supervisor. As a quality check, BI interventionists complete the BI checklist for each BI to capture the BI content and action plan/progress; they also participate in bi-weekly meetings with the BI trainer to receive ongoing supervision and monitoring.

2.6.5. SBIRT Intervention [4]

The minimal-risk S group is re-screened for substance use every 6 months, up to four times. Patients who screen positive for substance use at any follow-up visit then move to the SBI or the SBIRT group, as needed.

The at-risk SBI group is provided with a BI for reducing substance use or misuse, and they are re-screened for substance use every 6 months, up to four times. Patients who use substances at follow-up visits are provided with BI and/or RT, accordingly.

The high-risk SBIRT group are provided with a BI and RT at baseline. Within the first and second weeks of referral, the SBIRT group receives two phone calls to check on SUD treatment status and/or facilitate entry into SUD treatment.

This study includes one 20- to 30-minute BI session using Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET) delivered during the patient's visit to the diabetes clinic or home visit [4,51,52]. The first BI session focuses on establishing rapport, assessing patients' substance use attitudes and use patterns, exploring coexisting issues that may affect substance use behaviors and health conditions (e.g., diabetes), assessing motivation to change substance use, providing feedback as needed, assessing readiness to change, and collaboratively negotiating goals and a plan of action. Subsequent BI sessions are conducted on an individualized basis depending on results from re-screening, as well as motivation and progress on behavior change. Critical components includes assessing and addressing barriers to change, reviewing progress, providing feedback as needed, assessing readiness, re-establishing a plan of action as indicated, and affirming positive behavior change. For cigarette and drug users, the interventionist raises awareness as to the health and medical consequences of any use. For alcohol use, this study follows the American Diabetes Association's guidelines, which recommend that women have no more than 1 alcoholic drink per day, and that men have no more than 2 alcoholic drinks per day (one drink is equal to a 12 oz beer, 5 oz glass of wine, or 1 ½ oz distilled spirits) [53]. Lower (safer) limits of alcohol use among older adults aged 65 and older are advised: “no more than 1 standard drink or about 12 g of pure alcohol per day” for elders [54].

The goal for RT is to incorporate SUD treatment into a standard care setting for high-risk substance-using diabetic patients. Given that SBIRT services are new to this diabetic population, the interventionist works with patients to help them better understand SUD treatment. For patients who seem reluctant to pursue SUD treatment, the interventionist informs them that SUD treatment begins with a more thorough assessment of substance use and related problems before a treatment plan is prepared. The RT procedure includes providing the patient with an information sheet listing treatment programs (phone numbers, addresses) and SUD treatment service resources in their community. Patients are asked about their willingness to share the RT service information with their families or caretakers. Patients who express an interest or willingness to use SUD treatment are referred, as needed, by the study staff. Within the first two weeks of receiving the RT information, the SBIRT group receives up to two phone calls to check on patients' intention and use of SUD treatment services. The information collected during these phone calls is recorded in the patient's EDC data.

2.6.6. Intervention discontinuation

BI is discontinued if the patient withdraws consent, or if there is evidence that continuing in the study would be harmful to the participant.

2.6.7. Follow-up

Follow-up assessments are conducted every 6 months, up to 4 times, unless a patient withdraws consent or there is evidence that continuing in the study is harmful to the participant.

2.6.8. Substance use and clinical outcomes

The primary outcomes for substance use include changes in substance use (cigarette, alcohol, or drugs), severity (FTND, AUDIT-C, and DAST scores), and subsequent SUD treatment utilization. SUD-related medical complications from the EHR are explored. Diabetes outcomes include: medication adherence scores (collected by the parent study), healthcare use (number of emergency department and inpatient encounters), and diabetes-related complications (a summary of new diagnoses of medical conditions, including kidney disease, peripheral neuropathy, retinopathy or blindness, hypertension, heart failure, amputation, and stroke) from the EHR. Health related quality of life data are assessed by the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Global Health Short Form to explore their changes over time and associations with substance use and/or hospital admissions [55]

2.6.9. Stakeholder engagement

A Community Advisory Board (CAB) encompassing multiple community partners in Durham (e.g., non-profit community-based organizations, health and medical centers, faith-based organizations, partners serving people living with diabetes, community activists) has been convened to provide programming, leadership, and support for different constituencies impacted by diabetes. The study team (e.g., lead physician) participates in the CAB meetings and discusses the status of SEDI/DDC and SBIRT studies. In particular, the CAB members provide advice on issues related to barriers to care (e.g., transportation, access to medication, access to healthy food), community resources, study recruitment, and retention.

2.7. Data analysis

We will examine the feasibility and implementation of SBIRT by producing estimates of: recruitment time; demographic profiles to inform recruitment strategies for future trials; extent of “intervention exposure” (the extent to which planned interventions are delivered within the specified timeframe); data completion (the extent of participants who complete each of the substance use screening and assessment tools); retention (the extent to which participants remain in the study and complete follow-ups; the extent to which the clinical interventionists complete the planned brief intervention, referral to treatment services, and follow-up calls); and the number of participants entering SUD treatment.

We will conduct cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses to determine prevalence and incidence of substance use, problem substance use, and SUD (including persistence and cessation in use). The associations between SUD treatment use and substance use will be explored. We will explore cross-sectional and longitudinal associations of substance use status (use, problem use, SUD, treatment) with diabetic medication adherence, health related quality of life, emergency department/inpatient admissions, diabetes complications, and psychiatric comorbidity.

Lastly, to provide a more complete picture of patients' intervention needs and explore representativeness of the study sample, we will compare diabetes and substance use-related profiles of this sample with patients at the other three sites of SEDI that have not participated in the SBIRT study, as well as patients in the Duke University Health System's EHR data warehouse.

3. Discussion

The prevalence of diabetes among adults in the U.S. increased from 3.5% in 1980 to 9.0% in 2011 [12]. The total estimated cost of diagnosed diabetes was $245 billion in 2012, which reflects a 41% increase from a prior estimate in 2007. The largest components of medical expenditures are inpatient care [15]. Adults who have diabetes with complications or SUD tend to use more inpatient care than those without these diagnoses [21,22]. Cigarette smoking, heavy alcohol use, and alcohol/drug use disorder increase the likelihoods of medical complications [16]. Determining a feasible means of incorporating SBIRT into diabetes care can help minimize SUD-related consequences and reduce morbidity and costs. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration leads efforts to advance the behavioral health of people in the U.S. and has issued an advisory to encourage integrating diabetic care into behavioral healthcare settings [8]. Yet empirical data are needed to guide integration of SBIRT into primary care settings that treat medical conditions with high morbidity and mortality [56,57]. In line with the Institute of Medicine's vision for pursuing pragmatic clinical research in real-life settings to inform the development of learning healthcare systems [58], our study is designed to provide such first-hand clinical information about feasibility and potential challenges in conducting SBIRT among high-risk diabetic patients who have a pressing need for behavioral health interventions and care coordination.

3.1. What this study adds to our knowledge

Due to healthcare reforms (Affordable Care Act, parity law), high-quality integrated primary care (including home-based primary care) is considered a key solution to improving care for individuals with complex health conditions, including diabetes and SUDs [7,56–58]. SBIRT is considered a “primary care” approach to preventing substance-related problems and enhancing early intervention and utilization of evidence-based treatment; effective use of SBIRT may improve coordinated specialty care for SUDs and tracking outcomes [4,8,57]. Nevertheless, empirical data from studies conducted in real-life settings are needed to better understand the feasibility of implementing SBIRT and its consequent clinical impact. Furthermore, EHR can be a crucial tool not only for streamlining the SBIRT workflow through use of EHR-embedded decision algorithms, but for facilitating its implementation through health information sharing and documentation of clinical quality measures [1,2]. EHR data also provide a practical research resource for developing learning healthcare systems [58]. These shifting changes in healthcare delivery require the development of an innovative research paradigm for behavioral healthcare and SUDs that is conducted in clinical practices, taking into account patients' prior medical history and subsequent healthcare use and outcomes.

Our feasibility study is timely in multiple ways. First, it is in line with national priorities geared towards identifying ways SBIRT can be incorporated into primary care, focusing on common and costly chronic conditions (diabetes, SUDs) [5,8,59]. Second, since SBIRT among individuals with complex health needs in primary care is an unexplored area of clinical research, our study design represents a cost-effective way to leverage the existing resources of a larger diabetes study and an EHR warehousing platform to explore the challenges of implementing SBIRT within a chronic care framework. Third, the clinical data we obtain will be useful for informing the design and conduct of practical SBIRT studies for high-risk, high-cost patients with T2DM within a home-based primary care model [7]. As noted by the Institute of Medicine report [7], research is needed to inform home-based primary care models for improving the growing number of high-risk or aging patients with complex health needs. Finally, our study also will obtain valuable feasibility information regarding the use of EHR data to recruit eligible patients, the transmission of patient care data to a common EHR datamart for data analysis, and the use of ongoing treatment data for outcomes evaluation.

3.2. Limitations and strengths

Due to cost considerations, this SBIRT project uses an observational design and limits the scope of work to one study site; yet due to the focus on feasibility-exploration, the use of one site allows targeting participants for continuous follow-ups over a period of up to 2 years. The longitudinal design, coupled with the use of EHR data for tracking clinically important outcomes (e.g., diabetes related ED visits or inpatient care) are major strengths of this study, given that this coupling will provide information about recruitment, retention over time, and the impact of an integrated intervention on clinically meaningful outcomes available from EHRs. On the other hand, the findings from this study conducted in a home-based primary care setting in Durham County may not be generalizable to SBIRT delivered in traditional clinics or other settings. Nonetheless, the Triple Aim reform incentivizes developments of team-based, chronic care models that will address behavioral contributors (e.g., SUDs) to healthcare costs over time [6,7]. This study will make unique, timely contributions to the home-based primary care model, which is an emerging care delivery model that values cost-saving and person-centered care for adults with complex chronic illnesses [7]. Using an existing infrastructure from the larger SEDI study also facilitates the feasibility study to explore the use of a common EHR datamart for data collection and analysis. Given an increased emphasis on the importance of developing practice-based clinical trials, we describe an example of interdisciplinary collaboration aimed at producing clinical information to inform designs and implementation of integrated behavioral care and research efforts.

4. Summary

There is a clear need for developing integrated healthcare services to identify and target modifiable behavioral health problems that contribute to medical complications. The economic burden is expected to escalate as the prevalence of T2DM continues to rise, with costs being predominately driven by adults with comorbid chronic diagnoses, including SUD [60]. Integrated behavioral care has been understudied among patients living with DM. Our feasibility study constitutes an initial, practical step to produce the necessary data to inform designs of randomized SBIRT studies for understudied complex diabetic patients.

Acknowledgments

Robert M. Califf, MD, former Director of Duke Translational Medicine Institute and Vice Chancellor for Clinical and Translational Research, and Professor of Medicine in the Division of Cardiology at Duke University Medical Center, was Principal Investigator for the Southeastern Diabetes Initiative (SEDI). Dr. Califf is Deputy Commissioner for Medical Products and Tobacco at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Udi E. Ghitza is an employee of the Center for the Clinical Trials Network, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), which is the funding agency for the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network; his participation in this publication arises from his role as a project scientist on a cooperative agreement for this protocol. The authors thank support from the NIDA's Center for Clinical Trials Network (CCTN). The authors also thank Erin Hanley for assisting with the manuscript preparation.

Funding Sources This work was made possible by research support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health (U10DA013727; UG1DA040317; HHSN271201200017C, N01DA-12-2229; HHSN271201400028C, N01DA-14-223), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (1C1CMS331018), and the Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation. LT Wu also received support from the following NIH grants: R01MD007658, R01DA019623, R01DA019901, and R33DA027503. The sponsoring agencies have no further role in the study design and analysis, the writing of the report, or the decision to submit the paper for publication. The opinions expressed in this paper are solely those of the authors and do not represent the official position of the U.S. government and the Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Institutional review board approval: This NIDA CTN study (CTN-0057) has been approved by the Duke University Health System Institutional Review Board.

Competing interests: Susan E. Spratt reports receiving funds from the Exeter Group and Sanofi-Aventis for continuing medical education events in diabetes. The other authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [Accessed August 21, 2015];The Official Web Site for the Medicare and Medicaid Electronic Health Records (EHR) Incentive Programs. CMS.gov web site. CMS.gov http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/index.html?redirect=/ehrincentiveprograms.

- [2].Tai B, Wu LT, Clark HW. Electronic health records: essential tools in integrating substance abuse treatment with primary care. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2012;3:1–8. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S22575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [Accessed August 21, 2015];Population management in community mental health center-based health homes. SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions web site. http://www.integration.samhsa.gov/integrated-care-models/14_Population_Management_v3.pdf. Updated September 2014.

- [4].Shapiro B, Coffa D, McCance-Katz EF. A primary care approach to substance misuse. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88:113–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [Accessed August 21, 2015];SBIRT: Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment Opportunities for Implementation and Points for Consideration. Center for Integrated Health Solutions web site. http://www.integration.samhsa.gov/SBIRT_Issue_Brief.pdf.

- [6].Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [Accessed August 25, 2015];Hospital value-based purchasing. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/hospital-value-based-purchasing/index.html?redirect=/hospital-value-based-purchasing. Updated December 18, 2014.

- [7].Institute of Medicine and National Research Council . The Future of Home Health Care: Workshop Summary. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2015. 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [Accessed August 25, 2015];Diabetes care for clients in behavioral health treatment. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services web site. https://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content/SMA13-4780/SMA13-4780.pdf. Updated Fall 2013.

- [9].Powers BW, Chaguturu SK, Ferris TG. Optimizing high-risk care management. JAMA. 2015;313(8):795–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.18171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cohen SB. [Accessed August 25, 2015];Statistical Brief #448: Differentials in the Concentration of Health Expenditures across Population Subgroups in the U.S., 2012. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality web site. http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/st448/stat448.shtml. Updated September 2014. [PubMed]

- [11].Heron M. [Accessed August 25, 2015];Deaths: leading causes for 2010. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics web site. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr62/nvsr62_06.pdf. Updated December 20, 2013. [PubMed]

- [12].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Accessed August 25, 2015];National diabetes statistics report, 2014: estimates of diabetes and its burden in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention web site. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/statsreport14/national-diabetes-report-web.pdf.

- [13].Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, Gregg EW, Barker LE, Williamson DF. Projection of the year 2050 burden of diabetes in the US adult population: dynamic modeling of incidence, mortality, and prediabetes prevalence. Popul Health Metr. 2010;8:29. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-8-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].American Diabetes Association Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:S81–90. doi: 10.2337/dc14-S081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].American Diabetes Association Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2012. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1033–46. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ghitza UE, Wu LT, Tai B. Integrating substance abuse care with community diabetes care: implications for research and clinical practice. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2013;4:3–10. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S39982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Leung GY, Zhang J, Lin W, Clark RE. Behavioral disorders and diabetes-related outcomes among Massachusetts Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62:659–65. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.6.pss6206_0659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Leung GY, Zhang J, Lin W, Clark RE. Behavioral health disorders and adherence to measures of diabetes care quality. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17:144–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Pietraszek A, Gregersen S, Hermansen K. Alcohol and type 2 diabetes. A review. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;20:366–75. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Willi C, Bodenmann P, Ghali WA, Faris PD, Cornuz J. Active smoking and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2007;298:2654–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.22.2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Jiang HJ, Wier LM. [Accessed August 25, 2015];HCUP Statistical Brief #89: All-cause hospital readmissions among non-elderly Medicaid patients, 2007. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project web site. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb89.pdf. Updated April 2010. [PubMed]

- [22].Jiang HJ, Barrett ML, Sheng M. [Accessed August 25, 2015];HCUP Statistical Brief #184: Characteristics of hospital stays for nonelderly Medicaid super-utilizers, 2012. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project web site. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb184-Hospital-Stays-Medicaid-Super-Utilizers-2012.jsp. Updated November 2014.

- [23].Saitz R, Palfai TA, Cheng DM, et al. Screening and Brief Intervention for Drug Use in Primary Care: The ASPIRE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2014;312:502–513. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Roy-Byrne P, Bumgardner K, Krupski A, Dunn C, Ries R, Donovan D, West II, Maynard C, Atkins DC, Graves MC, Joesch JM, Zarkin GA. Brief intervention for problem drug use in safety-net primary care settings: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:492–501. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Konen J, Page J. The state of diabetes in North Carolina. N C Med J. 2011;72:373–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Barker LE, Kirtland KA, Gregg EW, Geiss LS, Thompson TJ. Geographic distribution of diagnosed diabetes in the U.S.: a diabetes belt. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:434–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Accessed August 25, 2015];CDC identifies diabetes belt. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention web site. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/diabetesbelt.pdf.

- [28].U.S. Census Bureau [Accessed March 12, 2015];State and County QuickFacts. Available at: http://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045214/37063.

- [29].Kountz D. Special considerations of care and risk management for African American patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Natl Med Assoc. 2012;104:265–73. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wu LT, Ghitza UE, Batch BC, Pencina MJ, Rojas LF, Goldstein BA, Schibler T, Dunham AA, Rusincovitch S, Brady KT. Substance use and mental diagnoses among adults with and without type 2 diabetes: Results from electronic health records data. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015 Sep 12; doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.09.003. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 26392231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Spratt SE, Batch BC, Davis LP, Dunham AA, Easterling M, Feinglos MN, et al. Methods and initial findings from the Durham Diabetes Coalition: integrating geospatial health technology and community interventions to reduce death and disability. J Clin Trans Endocrin. 2015;2:26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jcte.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Wagner EH, Coleman K, Reid RJ, Phillips K, Abrams MK, Sugarman JR. The changes involved in patient-centered medical home transformation. Prim Care. 2012;39:241–59. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Horvath MM, Rusincovitch SA, Brinson S, Shang HC, Evans S, Ferranti JM. Modular design, application architecture, and usage of a self-service model for enterprise data delivery: the Duke Enterprise Data Unified Content Explorer (DEDUCE) J Biomed Inform. 2014;52:231–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Rusincovitch SA, Shang HC. Conceptual model for research-driven data marts. Poster presented at: Healthcare Data Warehousing Association 2012 Annual Conference; Ottawa, Ontario. October 2–4, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Rusincovitch SA, Batch BC, Spratt S, Granger BB, Dunham AA, Davis LP, et al. Framework for curating and applying data elements within continuing use data: a case study from the Durham Diabetes Coalition. AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc. 2013;2013:228. eCollection 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Miranda ML, Ferranti J, Strauss B, Neelon B, Califf RM. Geographic health information systems: a platform to support the `triple aim'. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:1608–15. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Spratt SE, Shriver J, Maxon P, Batch B, Shah B, Califf R, et al. A risk model to identify patients with diabetes at highest risk for death or hospitalization: combining geography and risk to guide resources and improve outcomes [Abstract] American Diabetes Association. 2014 Jun; [Google Scholar]

- [38].De Jonge KE, Jamshed N, Gilden D, Kubisiak J, Bruce SR, Taler G. Effects of home-based primary care on Medicare costs in high-risk elders. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:1825–31. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Edwards ST, Prentice JC, Simon SR, Pizer SD. Home-based primary care and the risk of ambulatory care-sensitive condition hospitalization among older veterans with diabetes mellitus. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1796–803. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Yaggy SD, Michener JL, Yaggy D, Champagne MT, Silberberg M, Lyn M, et al. Just for Us: an academic medical center-community partnership to maintain the health of a frail low-income senior population. Gerontologist. 2006;46:271–6. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Ghitza UE, Gore-Langton RE, Lindblad R, Shide D, Subramaniam G, Tai B. Common data elements for substance use disorders in electronic health records: the NIDA Clinical Trials Network experience. Addiction. 2013;108:3–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Subramaniam G. The development of a clinical decision support for illicit substance use in primary care settings. Paper present at: 8th Annual Conference of International Network on Brief Interventions for Alcohol & Other Drugs; Boston, MA. September 21–23, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [43].U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [Accessed August 25, 2015];Helping patients who drink too much: a clinician's guide, updated 2005 edition. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism web site. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/CliniciansGuide2005/guide.pdf. Updated January 2007.

- [44].Fagerström KO, Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT. Nicotine addiction and its assessment. Ear Nose Throat J. 1990;69:763–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Zhou Y. Effectiveness of the derived Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) in screening for alcohol use disorders and risk drinking in the US general population. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:844–54. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000164374.32229.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Dawson DA, Smith SM, Saha TD, Rubinsky AD, Grant BF. Comparative performance of the AUDIT-C in screening for DSM-IV and DSM-5 alcohol use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;126:384–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Smith PC, Schmidt SM, Allensworth-Davies D, Saitz R. A single question screening test for drug use in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1155–60. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Skinner HA. The drug abuse screening test. Addict Behav. 1982;7:363–71. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Yudko E, Lozhkina O, Fouts A. A comprehensive review of the psychometric properties of the Drug Abuse Screening Test. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;32:189–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Arozullah AM, Yarnold PR, Bennett CL, Soltysik RC, Wolf MS, Ferreira RM, Lee SY, Costello S, Shakir A, Denwood C, Bryant FB, Davis T. Development and validation of a short-form, rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine. Med Care. 2007;45(11):1026–33. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3180616c1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Miller WR, Zweben A, DiClemente CC, Rychtarik RG. [Accessed August 25, 2015];Motivational enhancement therapy manual: a clinical research guide for therapists treating individuals with alcohol abuse and dependence. Motivational Interviewing web site. http://www.motivationalinterviewing.org/sites/default/files/MATCH.pdf.

- [52].Rubak S, Sandbaek A, Lauritzen T, Christensen B. Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55:305–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].American Diabetes Association [Accessed August 25, 2015];Alcohol. American Diabetes Association web site. http://www.diabetes.org/food-and-fitness/food/what-can-i-eat/making-healthy-food-choices/alcohol.html. Updated June 6, 3014.

- [54].Crome I, Li TK, Rao R, Wu LT. Alcohol limits in older people. Addiction. 2012;107:1541–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Hinami K, Smith J, Deamant CD, DuBeshter K, Trick WE. When do patient-reported outcome measures inform readmission risk? J Hosp Med. 2015;10(5):294–300. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Institute of Medicine [Accessed August 25, 2015];Primary care and public health: exploring integration to improve population health. Institute of Medicine web site. https://iom.nationalacademies.org/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2012/Primary-Care-and-Public-Health/Primary%20Care%20and%20Public%20Health_Revised%20RB_FINAL.pdf. Updated March 2012. [PubMed]

- [57].Tai B, Sparenborg S, Ghitza UE, Liu D. Expanding the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network to address the management of substance use disorders in general medical settings. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2014;5:75–80. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S66538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Institute of Medicine . The Learning Healthcare System: Workshop Summary (IOM Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine) National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Ghitza UE, Tai B. Challenges and opportunities for integrating preventive substance-use-care services in primary care through the Affordable Care Act. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2014;25:36–45. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2014.0067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Ashman JJ, Talwalkar A, Taylor SA. [Accessed August 25, 2015];NCHS Data Brief, NO. 161: Age differences in visits to office-based physicians by patients With diabetes: United States, 2010. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention web site. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db161.pdf. Updated July 2014. [PubMed]