Abstract

Objective

This study examines the psychometric properties of a measure of distress specific to cancer and its treatment, as tested in patients receiving hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT).

Methods

With multicenter enrollment, the Cancer and Treatment Distress (CTXD) measure was administered to adults beginning HCT as part of an assessment that included the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CESD), Profile of Mood States (POMS) and Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 (SF-36).

Results

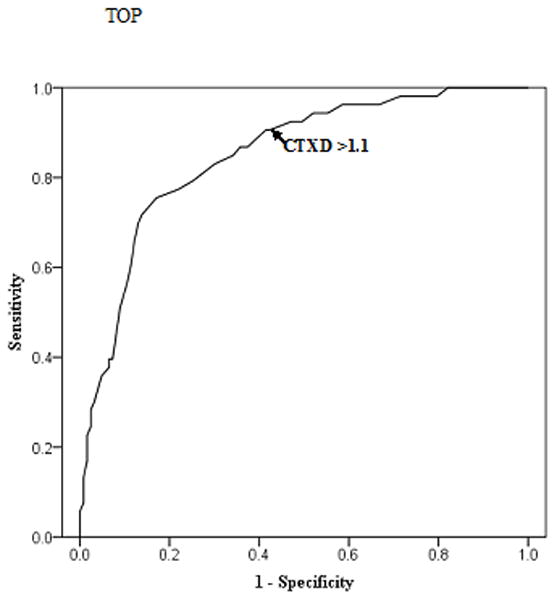

From eight transplant centers, 176 of 219 eligible patients completed the assessment. Average age was 46.7 (SD=11.9), 59% were male, the majority identified as Caucasian (93%). Principal components analysis with the CTXD identified 22 items that loaded onto six factors explaining 69% of the variance: uncertainty, health burden, identity, medical demands, finances, and family strain. Internal consistency reliability for the 22 items was 0.91. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) area under the curve was 0.85 (95% confidence interval: 0.79, 0.91), with a cut point of 1.1 resulting in sensitivity of 0.91 and specificity of 0.58. Convergent and divergent validity were confirmed with large correlations of the CTXD total score with the CESD, POMS and SF-36 mental health, and a smaller correlation with the SF-36 physical function (r = −0.30).

Conclusion

The CTXD is a reliable and valid measure of distress for HCT recipients and captures nearly all cases of depression on the CESD in addition to detecting distress in those who are not depressed. It has potential value as both a research and clinical screening measure for distress.

Keywords: distress, cancer, oncology, psychometric, depression, hematopoietic cell transplantation

BACKGROUND

Distress related to cancer and its treatment is one of the more common symptoms experienced across the cancer continuum from diagnosis through survivorship or end of life. Although cancer-related distress is widely recognized as a syndrome meriting routine screening with access to psychosocial services when needed, surprisingly few measures have been designed to measure the multiple dimensions of this distress specific to cancer. As a result, diverse measures are used in research and clinical care from standardized measures of anxiety, depression or trauma to oncology-specific measures of quality of life [1,2]. Most commonly, the distress thermometer has been used as developed with the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Distress Guideline [3].

The need to detect and treat elevated cancer-related distress is supported by many studies demonstrating poorer outcomes in cancer patients with elevated distress, including worse adherence to treatment recommendations, impaired quality of life and decreased satisfaction with care, in addition to poorer survival in some studies [4,5]. Studies have demonstrated that distress in cancer patients is often not recognized since up to 45% of cancer patients report distress during treatment, but less than 10% are referred to treatment for this distress [6]. Based on the evidence of negative consequences and documented under-treatment, the regular monitoring of distress is now mandated by the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer, for accreditation of health care organizations [7]. This makes the availability of adequate measures of this distress a more pressing need.

As defined by the NCCN Distress Guideline, distress extends along a continuum, ranging from common feelings of vulnerability, sadness, and fears of recurrence to disabling depression, anxiety, trauma, panic, and existential crisis [3]. Cancer-related distress has qualities of vulnerability, worry, frustration, trauma and fear of recurrence that may not be fully captured by standard measures of clinical depression or anxiety [8]. Recent investigators have examined the sensitivity and specificity of the distress thermometer (DT) [9], including with hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) recipients [9–12], with some noting its sensitivity but not its specificity[1,13,14]. HCT has been well defined as a stressful process with high risk of mortality and long-term complications [15,16].

Since the DT may not be effective on its own because the high rate of false positives could render the single item difficult to use in practice [5], Mitchell encourages the use of another instrument to be able to more clearly detect patients with significant distress [14]. The DT may also not be a good fit in the research setting where differences in treatment or changes over time are of interest rather than a quick screening tool. Other measures of distress that have been used with cancer and HCT populations include the Profile of Mood States [17–19], the Functional Assessment of Cancer Treatment (FACT) [20], the Impact of Events Scale [21], and the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) [11,22,23]. While the FACT is cancer-specific and has a module for HCT patients, it is intended to measure quality of life rather than emotional distress. The other measures are intended for broad cross-population use, not specifically to capture cancer-related distress. It remains unclear whether there are meaningful dimensions of cancer-related distress that are not captured in measures of psychological distress intended for general populations.

The aim of this research has been to define an optimally parsimonious distress measure that captures the multiple dimensions of distress in cancer patients receiving HCT. The CTXD is intended to detect clinically meaningful levels of depression and anxiety in addition to capturing cancer-related distress domains that may not be reflected in general measures of these clinical syndromes. This paper describes the development and psychometric properties of the Cancer and Treatment Distress (CTXD) measure, including principal components analysis, internal consistency reliability, concurrent and divergent validity, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) for determining the optimal sensitivity and specificity cut point for identifying elevated distress.

METHODS

Design and Participants

The CTXD was part of a baseline assessment conducted in the ambulatory clinic 2–14 days before patients began transplant-related treatment, following patient consent to participate in a parent study designed to test a psychoeducational intervention targeted to patients and their caregivers. Eight transplant centers in the United States enrolled patients who were entering their first HCT. The assessment point pretransplant occurred at the peak of distress for HCT recipients [24]. The Institutional Review Board at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and each participating site approved all study procedures and forms.

Nurse study coordinators screened all transplant recipients at each site who were scheduled to receive a myeloablative chemotherapy preparative regimen. Eligible participants were 18 years or older, receiving their first HCT for a malignancy, had sufficient English to complete assessments, and were living in the United States with a primary caregiver for at least 3 months after returning home. Patients were excluded if, based on medical records, they had a major psychiatric diagnosis, had a history of alcohol or drug abuse, were deaf or blind (since the intervention used print and video materials with phone calls), had major cognitive deficits, refused consent for caregiver participation in the primary study, or were too ill to consent and complete assessments. Patients were approached for consent within constraints of the study coordinators’ ability to contact them before treatment started.

Measures

Development of the Cancer and Treatment Distress (CTXD) Measure

To capture the distress related to HCT, we developed a measure over a number of years and studies with iterations used in prospective longitudinal research protocols that are not presented in this analysis. The development of the CTXD began with qualitative interviews with 48 patients who were asked about the aspects of their diagnosis and treatment that were difficult or distressing for them. Physicians, nurses and other health care providers were asked for their input about any content areas that were missed. Items were then generated based on the content of these interviews into a BMT Distress measure [24,25]. The iterations occurred with continuing qualitative feedback from patients, identifying distressing items that were missing and framing those items in wording that was relevant to patients, while deleting items that were rarely endorsed in testing. A further intent of item selection was to strengthen the subscale factor structure of the measure to include relevant domains and to have strong psychometric properties. A goal of the CTXD development was that it retain psychometric strength over time from diagnosis through treatment and recovery, although longitudinal properties are not the focus of this paper. The CTXD administered in the study reported here included 46 items (see Supplemental Table). Instructions were “Below are thoughts many people have during or after treatment. For each thought below, please circle how much distress or worry (such as feeling upset, tense, sad, frustrated) it caused you in the past week, even if the event has not happened.” Responses were scored 0–3 indicating none, mild, moderate, or severe distress.

Other Patient-Reported Outcomes Measures

Patients provided reports of demographic data, the CTXD and standardized measures. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CESD) was developed for use with the general population, and measures 20 depressive symptoms within the past week [26]. Hann and colleagues demonstrated the scale’s reliability in both breast cancer and healthy comparison samples [27]. Scores can range from 0 to 60, with scores ≥ 16 categorized as depressed. The Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36) measured eight dimensions of health related quality of life, withmental and physical component summaries [28]. The measure has undergone extensive reliability and validity testing, has been used with cancer patients, and has general population norms [28]. The Profile of Mood States Short Form (POMS) is a 30-item measure of mood [29]. Respondents rate the extent to which they experienced each of the 30 feelings such as “nervous” or “sad” during the past week [29]. The POMS has been used with reliability and validity in HCT and other cancer samples [30].

Medical Records Data

Site nurse coordinators abstracted medical records to determine diagnosis, treatment regimen, type of stem cell donor, and source of stem cells.

Statistical Analysis

Data analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics version 22 (Armonk, NY). Site differences in measures were compared using one-way analysis of variance. The sample size was appropriate for factor analysis based on criteria established by Sapnas and Zeller [31]. We used principal components analysis with a promax rotation since the factor structure was unknown a priori, but we assumed that factors would be correlated. Factors with eigenvalues greater than one were retained, and communalities and total variance explained were considered as part of the psychometric analyses. An iterative process defined the set of items with factor loadings ≥0. 50 and maximum parsimony that added explained variance to the overall measure. Internal consistency reliabilities of the CTXD total mean and the subscales were tested using Cronbach’s α. ROC was analyzed using the CESD score of ≥16 as the standard for determining sensitivity and specificity of the CTXD since it has the clearest cut point for determining clinically meaningful distress of the measures collected [26]. To determine convergent validity, we examined correlations between the CTXD and established measures of distress and depression including the CESD, POMS and SF-36 mental health subscale. For discriminant validity, we examined correlations between the CTXD and the SF-36 physical function subscale. Cohen’s criterion [32] was used to interpret the magnitude of correlation coefficients (r<0.3 = small; r>0.3 and <0.5 = medium; and r≥0.5 = large).

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Of 219 potentially eligible patients, 176 patients consented to participate and completed the baseline CTXD and other measures. Table 1 provides demographic and medical information for the participants. Over half (59%) were male, the average age was 46.7 (SD=11.9), and the majority identified as Caucasian (93%) and had more than a high school education (69%). Participation by sites varied widely from enrolling 2 to 68 participants. The SF-36 mental health, physical function, physical component summary, mental component summary, POMS and CEDS scores did not differ by site (all analyses of variance P >.10 across sites).

Table 1.

Demographic and medical characteristics (N=176)

| Age at assessment, mean (SD) | 46.7 (11.9) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 104 (59) |

| Female | 72 (41) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White/Caucasian | 164 (93) |

| Asian | 5 ( 3) |

| African American | 3 ( 2) |

| Native American | 4 ( 2) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 175 (99) |

| Hispanic | 1 ( 1) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| High school or less | 54 (31) |

| 2 year college or trade degree | 40 (23) |

| 4 year degree or more | 82 (47) |

| Income, n (%) | |

| ≤ $44,999 | 34 (19) |

| ≥ $45,000 and ≤ $99,999 | 192 (53) |

| ≥ $100,000 | 49 (28) |

| Marital status, n ( %) | |

| Married or living with partner | 163 (93) |

| Single or divorced | 13 (7) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 43 (24) |

| Multiple myeloma | 32 (18) |

| Myelodysplasias | 28 (16) |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 27 (15) |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 13 (7) |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 12 (7) |

| Acute lymphocytic leukemia | 11 (6) |

| Other | 10 (6) |

| Donor type, n (%) | |

| Autologous | 79 (45) |

| Allogeneic | 97 (55) |

| Source of cells, n (%) | |

| Peripheral blood | 158 (90) |

| Bone marrow | 13 (7) |

| Cord blood | 5 (3) |

| Site enrolled from, n (%) | |

| Site 1 | 68 (39) |

| Site 2 | 41 (23) |

| Site 3 | 32 (18) |

| Site 4 | 13 (7) |

| Site 5 | 9 (5) |

| Site 6 | 7 (4) |

| Site 7 | 4 (2) |

| Site 8 | 2 (1) |

CTXD Factor Analysis and Reliability

Means and standard deviations for all tested 46 items can be seen in the Supplemental Table. The maximally parsimonious version has 22 items, with item means ranging from 0.61–1.90 and standard deviations from 0.72–1.03. For the principal components analysis with promax rotation, the pattern matrix factor loadings for individual items ranged from 0.50 to 0.99 (Table 2). The communalities of the items ranged from 0.53–0.83. Six factors emerged, explaining 69% of the total variance and with eigenvalues between 1.0 and 8.0. Additional items did not improve the variance explained or factor structure. Internal consistency reliabilities for the factors and total mean score with 22 items were: uncertainty α =0.87, health burden α =0.84, identity α =0.81, medical demands α =0.80, finances α =0.79, family strain α =0.77, and total mean score α =0.91. Correlations between subscale factors ranged from 0.25 (finances and health burden) and 0.55 (identity and family strain) as seen in Table 3.

Table 2.

Pattern matrix factor loadings of the CTXD items using promax rotation with 22 items and six subscales

| Uncertainty | Family Strain | Health Burden | Finances | Medical Demands | Identity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not knowing what the future will bring | 0.92 | −.11 | .02 | .06 | .−.15 | .03 |

| Thoughts about the possibility of dying | 0.84 | −.01 | .04 | −.01 | −.05 | .01 |

| Long term effects of treatment | 0.77 | −.26 | .09 | .07 | .10 | .03 |

| Thinking about the possibility of recurrence | 0.74 | .22 | −.06 | −.05 | .15 | −.14 |

| Thinking about possible things that could go wrong | 0.70 | .−02] | −.09 | .07 | .16 | −.14 |

| Medical problems | 0.63 | .22 | −.10 | −.07 | .10 | −.03 |

| The family having to help out more than in the past | −.11 | 0.91 | .02 | .01 | .03 | −.03 |

| Wondering about the emotional toll on my family or other caregivers | .17 | 0.67 | −.09 | .03 | .14 | −.09 |

| Being a burden to other people | .03 | 0.65 | .22 | .06 | −.03 | .10 |

| Feeling tired and worn out | −.10 | −.08 | 0.92 | .04 | .05 | .03 |

| Not having my usual energy | −.10 | 04 | 0.90 | −.02 | .03 | .05 |

| Not being able to do what I used to do | .22 | .10 | 0.75 | −.05 | .00 | −.21 |

| The cost of my health care | −.02 ] | −.04] | .03 | 0.90 | .01 | −.03 |

| Dealing with insurance | −.10 | .17 | −.10 | 0.82 | −.03 | .09 |

| Wondering how to support myself and the family financially | .13 | −.04 | .05 | 0.79 | .01 | −.10 |

| Getting information when I need it | .01 | .11 | −.13 | −.01 | 0.84 | .02 |

| Communicating with medical people | −.13 | .12 | .04 | .00 | 0.84 | .00 |

| Dealing with the medical system | .10 | −.15 | .21 | .00 | 0.76 | .02 |

| My hair thinning or falling out | −.11 | −.16 | −.07 | .02 | .08 | 0.99 |

| Changes in my appearance | .08 | .03 | −.06 | −.06 | .01 | 0.86 |

| Losing “myself” in all of the changes | .20 | .24 | .03 | .00 | −.04 | 0.53 |

| Not feeling as masculine or feminine as I used to feel | .03 | .13 | .32 | .00 | −.14 | 0.50 |

Table 3.

Validity correlations of the Cancer and Treatment Distress (CTXD) with the Short From-36 (SF-36), Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CESD), and Profile of Mood States (POMS), and subscale intercorrelations with the CTXD

| CTXD Scales | SF-36 Physical Functiona | SF-36 Mental Healtha | CESD | POMS | Uncertainty | Family Strain | Health Burden | Finances | Medical Demands | Identity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Mean | −0.30*** | −0.55*** | 0.66*** | 0.62*** | 0.83*** | 0.78*** | 0.68*** | 0.61*** | 0.65*** | 0.76*** |

| Uncertainty | −0.16* | −0.57*** | 0.62*** | 0.54*** | ||||||

| Family Strain | −0.22** | −0.43*** | 0.51*** | 0.43*** | 0.54*** | |||||

| Health Burden | −0.395*** | −0.35*** | 0.52*** | 0.53*** | 0.42*** | 0.53*** | ||||

| Finances | −0.15* | −0.17* | 0.23** | 0.25*** | 0.34*** | 0.41*** | 0.25*** | |||

| Medical Demands | −0.23** | −0.21** | 0.33*** | 0.36*** | 0.47*** | 0.44*** | 0.37*** | 0.37*** | ||

| Identity | −0.21** | −0.49*** | 0.57*** | 0.49*** | 0.53*** | 0.55*** | 0.50*** | 0.37*** | 0.33*** |

P<0.05,

P≤0.01,

P≤0.001

Note that for the SF-36 a higher score indicates better function whereas for all other measures a higher score indicates more distress or poorer function.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC)

The ROC analysis, used a CESD of 16 or greater as the state indicator of distress, indicated that a CTXD mean score cut point of 1.1 resulted in a sensitivity (true positive) rate of 0.91 and a specificity (true negative) of 0.58 (Figure 1). The ROC area under the curve was 0.85 (95% Confidence Interval: 0.79, 0.91). The negative predictive value of the CTXD relative to the CESD was 93.4% while the positive predictive value was 48.0%.

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve illustrating that a Cancer and Treatment Distress (CTXD) mean score cut point of 1.1 results in a sensitivity of 0.91 and a specificity of 0.58 using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression standard cut point of 16. ROC area under the curve is 0.85 (95% Confidence Interval: 0.79, 0.91).

CTXD Validity

Table 3 contains the correlations for the CTXD. In testing convergent validity, the CTXD total mean and subscales were correlated as expected with non-cancer-specific measures of distress and depression. Using Cohen’s criteria, correlations between the total mean and the SF-36 mental health, CESD and POMS were in the large range. Correlations between the CTXD subscales and the SF-36 mental health, CESD and POMS were in the large or medium range with the exception of the finances subscale and the medical demands subscale correlations with the SF-36 mental health subscale. Using Cohen’s criteria in examining divergent validity, all SF-36 physical function correlations with CTXD scores were in the small range, with the exception of the subscale health burden, which was in the medium range (r=−0.36) and physical function with the total mean which was on the border between small and medium (r=−0.30).

CONCLUSIONS

This study examined cancer and treatment distress in patients just prior to beginning HCT, a point of peak distress. The CTXD demonstrated clear and strong factor structure with six subscales: uncertainty, family strain, health burden, finances, medical demands and identity. Internal consistency reliability met standards for measurement strength with all subscale reliabilities above 0.70 and the total score reliability of 0.91. The CTXD using a cut point of >1.10 had sensitivity of 0.91, capturing the large majority of cases of elevated depression on the CESD and also demonstrating large correlations with measures of general mood and psychosocial quality of life. As expected, the CTXD also captured cases of high distress without parallel elevated depression, with specificity of 58%, suggesting that the CTXD is measuring qualities of distress distinct from depression.

As indicated with the ROC sensitivity and specificity analyses, the CTXD is highly sensitive in capturing depression and less specific in that there are numerous cases without depression that have elevated scores for distress. This lack of specificity is of concern in screening for distress, particularly with the distress thermometer [1]. Pandey and colleagues [33] have suggested that distress shares variance with depression and anxiety and they may be similar constructs. The research in this area is mixed as Akizuki and colleagues [34] found that the distress thermometer had more sensitivity and specificity than the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and their sample included HCT patients. The CTXD was not directly compared with the distress thermometer in this study. However, with the CTXD cut point of greater than 1.1, 56% of those assessed would require further screening at the time point of peak distress (pretransplant) for one of the most arduous forms of treatment available for cancer, while the CESD would have referred 30% for further screening. Other research has identified elevated psychological distress in 52–59% of patients beginning HCT treatment [11,12]. Given the fact that in many settings, all patients entering HCT receive some form of psychosocial evaluation, the rate of 56% may be appropriate. Of note, the content of the CTXD is not HCT specific and can be used for other cancer treatments and diagnostic groups.

It remains to be demonstrated with direct comparison to clinical screening interviews whether the CTXD captures cases of clinical anxiety, depression or trauma that disrupt function and quality of life in cancer patients with greater specificity and less patient response burden than administering a set of measures to capture each of these conditions separately. If this is the case, it may be of value as a screening tool in clinical use as well as for research. A further point is that the CTXD subscales provide potential value in identifying domains in which a patient’s distress is elevated or in determining changes over time in domains of concern. More research is needed in this area to obtain a clearer picture of the overlap in these constructs of distress in cancer and specifically HCT patients.

There are several limitations of the study. The sample lacked ethnic and racial diversity and was highly educated. The CTXD should also be tested with patients with other treatments than HCT to determine whether the factor structure is maintained and the applicability of the CTXD content to other cancer groups. The CTXD has been translated into German and used with similar results [35], but studies in other languages and with greater patient cultural diversity are needed. In addition, a validation study of the CTXD and the DT would be very useful. Future studies should address the nature of distress over time, as stressors may differ during acute treatment relative to the survivorship phase of the cancer continuum, and research has demonstrated a general decrease in distress over time [36,37]. Furthermore, future work may determine distinctions in perceptions of distress for different subgroups of patients, for instance, by age, gender, cultural identification or other qualities beyond shifts over time [38].

In conclusion, the CTXD is a useful measure in either the research or clinical setting where it can provide screening for determining areas of need for psychosocial support as mandated by the American College of Surgeons, Commission on Cancer. This study indicates that the CTXD will capture the large majority of cases of depression, as measured by the CESD, and general distress as reflected by the large size POMS correlation. Screening of distress is recommended not only to identify patients needing referral, but also because filling out and reviewing a measure can help to normalize the experience of distress and validate the importance of psychosocial concerns [39]. Under-treatment of distress is well recognized in oncology [40], and measures such as the CTXD can expedite decisions about psychosocial interventions. Using screening tools with validated cut-points for cancer patients, whether the Distress Thermometer or the CTXD, can define patients who need for referral to a social worker or other mental health provider for further evaluation. Since the CTXD captures elevated depression, a referral to a social worker or other mental health provider should occur with scores >1.10, whereas direct referral to a psychologist or psychiatrist might occur for scores one standard deviation above norms (>1.74) if these resources are available. In clinical practice, we use the CTXD to screen cancer survivors and not only provide the clinician with the scores but also list the items endorsed as causing ‘severe’ distress. This provides a clinician with content for discussion and can help to discriminate referral needs. For example, if only uncertainty items are elevated, referral to a chaplain might be considered if a patient is receptive. If primarily financial or family strain items are the focus of distress, this is valuable information for a social work referral. While there are numerous measures of mental health that can be considered for screening cancer patients, the advantage of the Distress Thermometer is its brevity and a measure such as the CTXD is its relevant clinical and research content. As part of routine care, the use of distress screening tools such as the CTXD electronically administered at entry to treatment and at major shifts in care, with an immediate summary report to the clinician, can not only determine need for referral but can also facilitate discussion of distressing topics that may be readily addressed with patient and health care provider communication.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: National Cancer Institute grants CA63030, CA78990, CA160684.

We thank the participants in the study and the investigators who were instrumental in facilitating enrollment at their transplant centers: Alfred Marcus PhD (AMC Cancer Research Center), Roger Dansey MD (Karmanos Cancer Institute), Jeffery Matous MD (Rocky Mountain Cancer Center), Karl Blume MD (Stanford), John Wingard MD (University of Florida), Samuel Silver MD (University of Michigan), Finn Peterson MD (University of Utah), and Richard McQuellon PhD (Wake Forest University).

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

This work has not been published or submitted elsewhere.

References

- 1.Carlson LE, Waller A, Mitchell AJ. Screening for distress and unmet needs in patients with cancer: Review and recommendations. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:1160–1177. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell AJ. Short screening tools for cancer-related distress: a review and diagnostic validity meta-analysis. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2010;8:487–49. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holland JC, Andersen B, Breitbart WS, Buchmann LO, Compas B, Deshields TL, Dudley MM, Fleishman S, Fulcher CD, Greenberg DB, Greiner CB, Handzo GF, Hoofring L, Hoover C, Jacobsen PB, Kvale E, Levy MH, Loscalzo MJ, Mcallister-Black R, Mechanic KY, Palesh O, Pazar JP, Riba MB, Roper K, Valentine AD, Wagner LI, Zevon MA, Mcmillan NR, Freedman-Cass DA. Distress management. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2013;11:190–209. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johansson M, Ryden A, Finzia C. Mental adjustment to cancer and its relation to anxiety, depression, HRQL and survival in patients with laryngeal cancer - a longitudinal study. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:283. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobsen PB. Screening for psychological distress in cancer patients: challenges and opportunities. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:4526–452. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlson LE, Bultz BD. Cancer distress screening. Needs, models, and methods. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2003;55:403–409. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(03)00514-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American College of Surgeons. Cancer Program Standards 2012, Version 1.2.1: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care. 2012. [Accessed on 1/15/2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savard J, Ivers H. The evolution of fear of cancer recurrence during the cancer care trajectory and its relationship with cancer characteristics. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2013;74:354–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobsen PB, Donovan KA, Trask PC, Fleishman SB, Zabora J, Baker F, Holland JC. Screening for psychologic distress in ambulatory cancer patients. Cancer. 2005;103:1494–1502. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ransom S, Jacobsen PB, Booth-Jones M. Validation of the Distress Thermometer with bone marrow transplant patients. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15:604–612. doi: 10.1002/pon.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bevans M, Wehrlen L, Prachenko O, Soeken K, Zabora J, Wallen GR. Distress screening in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell (HSCT) caregivers and patients. Psycho-Oncology. 2011;20:615–622. doi: 10.1002/pon.1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crooks M, Seropian S, Bai M, McCorkle R. Monitoring patient distress and related problems before and after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Palliative & Supportive Care. 2014;12:53–61. doi: 10.1017/S1478951513000552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butt Z, Wagner LI, Beaumont JL, Paice JA, Peterman AH, Shevrin D, Von Roenn JH, Carro G, Strauss JL, Muir JC, Cella D. Use of a single-item screening tool to detect clinically significant fatigue, pain, distress, and anorexia in ambulatory cancer practice. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management. 2008;35:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell AJ. Pooled results from 38 analyses of the accuracy of distress thermometer and other ultra-short methods of detecting cancer-related mood disorders. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:4670–4681. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin PJ, Counts GW, Applebaum FR, Lee SJ, Sanders JE, Deeg HJ, Flowers MED, Syrjala KL, Hansen JA, Storer BE. Life expectancy in patients surviving more than 5 years after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Journal of Clinical Oncoogy. 2010;28:1011–1016. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.6693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Syrjala KL, Martin PJ, Lee SJ. Delivering care to long-term adult survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:3746–3751. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.3038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cella DF, Jacobsen PB, Orav EJ, Holland JC, Silberfarb PM, Rafla S. A brief POMS measure of distress for cancer patients. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1987;40:939–942. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baker F, Marcellus D, Zabora J, Polland A, Jodrey D. Psychological distress among adult patients being evaluated for bone marrow transplantation. Psychosomatics. 1997;38:10–19. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(97)71498-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker F, Denniston M, Zabora J, Polland A, Dudley WN. A POMS short form for cancer patients: psychometric and structural evaluation. Psycho-Oncology. 2002;11:273–281. doi: 10.1002/pon.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McQuellon RP, Russell GB, Cella DF, Craven BL, Brady M, Bonomi A, Hurd DD. Quality of life measurement in bone marrow transplantation: development of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-bone marrow transplant [FACT - BMT] scale. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;19:357–368. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sherman AC, Simontin S, Latif U, Plante TG, Anaissie EJ. Changes in quality-of-life and psychosocial adjustment among multiple myeloma patients treated with high-dose melphalan and autologous stem cell transplantation. Biology of Blood & Marrow Transplantation. 2009;15:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DuHamel KN, Mosher CE, Winkel G, Labay LE, Rini C, Meschian YM, Austin J, Greene PB, Lawsin CR, Rusiewicz A, Grosskreutz CL, Isola L, Moskowitz CH, Papadoulos EB, Rowley S, Sigliano E, Burkhalter JE, Hurley KE, Bollinger AR, Redd WH. Randomized clinical trial of telephone-administered cognitive-behavioral therapy to reduce post-traumatic stress disorder and distress symptoms after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:3754–3761. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.8722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun CL, Francisco L, Baker KS, Weisdorf DJ, Forman SJ, Bhatia S. Adverse psychological outcomes in long-term survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation: a report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study (BMTSS) Blood. 2011;118:4723–4731. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Syrjala KL, Langer SL, Abrams JR, Storer B, Sanders JE, Flowers MED, Martin PJ. Recovery and long-term function after hematopoietic cell transplantation for leukemia or lymphoma. JAMA. 2004;291:2335–2343. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.19.2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Syrjala KL, Chapko ME. Evidence for a biopsychosocial model of cancer treatment-related pain. Pain. 1995;61:69–79. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00153-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hann D, Winter K, Jacobsen P. Measurement of depressive symptoms in cancer patients: Evaluation of the Center for Epidemiology Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) Journal of Psychsomatic Research. 1999;46:437–443. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinki M. SF-36 health survey: manual and interpretation guide. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 29.McNair D, Lorr M, Droppleman L. Profile of Mood States (POMS) San Diego: EdITS/Educational and Industrial Testing Service; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curran S, Andrykowski M, Studts J. Short Form of the Profile of Mood States (POMS-SF) Pychometric Information. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:80–83. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sapnas KG, Zeller RA. Minimizing sample size when using exploratory factor analysis for measurement. Journal of Nursing Measurement. 2002;10:135–154. doi: 10.1891/jnum.10.2.135.52552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pandey M, Devi N, Thomas BC, Kumar SV, Krishman R, Ramdas K. Distress overlaps with anxiety and depression in patients with head and neck cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2007;16:582–586. doi: 10.1002/pon.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akizuki N, Yamawaki S, Akechi T, Nakano T, Uchitomi Y. Development of an impact thermometer for use in combination with the distress thermometer as a brief screening tool for adjustment disorders and/or major depression in cancer patients. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management. 2005;29:91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rischer J, Scherwath A, Zander AR, Koch U, Schulz-Kindermann F. Sleep disturbances and emotional distress in the acute course of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;44:121–128. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McQuellon RP, Russell GB, Rambo TD, Craven BL, Radford J, Perry JJ, Cruz J, Hurd DD. Quality of life and psychological distress of bone marrow transplant recipients: the ’time trajectory’ to recovery over the first year. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;21:477–486. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lynch BM, Steginga SK, Hawkes AL, Pakenham KI, Dunn J. Describing and predicting psychological distress after colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2008;112:1363–1370. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.VanHoose L, Black LL, Doty K, Sabata D, Twumasi-Ankrah P, Taylor S, Johnson R. An analysis of the distress thermometer problem list and distress in patients with cancer. Supportive Care Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2471-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryan H, Schofield P, Cockburn J, Butow P, Tattersall M, Truner J, Girgis A, Bandaranayake D, Bowman D. How to recognize and manage psychological distress in cancer patients. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2005;14:7–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2005.00482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carlson LE, Angen M, Cullen J, Goodey E, Koopmans J, Lamont L, Macrae JH, Martin M, Pelletier G, Robinsob J, Simpson JSA, Speca M, Tillotson L, Bultz BD. High levels of untreated distress and fatigue in cancer patients. British Journal of Cancer. 2004;90:2297–2304. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.