Voluntary euthanasia became legal in Quebec in December 2015,1 although the legislation is currently the subject of litigation. In addition, physician-assisted death will become legal across Canada in February 2016,2 barring an extension on the deadline being given by the Supreme Court of Canada. There are many questions about how physician-assisted death should be regulated. One as-yet-unanswered question is “Should physician-assisted death be recorded anywhere on the medical certificate of death?” If so, a second question follows: “How should it be recorded — as manner and/or cause?” and if the latter, “Which category of cause: immediate, antecedent or underlying?”

To address these questions, we reviewed the purposes of medical certificates of death, the various medical certificates of death in use across Canada, death certificates in jurisdictions that already permit physician-assisted death and the law with respect to life insurance in Canada and abroad. We found that, by turning to first principles and established practices regarding completion of medical certificates of death, we were able to find sensible answers to these questions.

Terminology

For the purposes of this paper, we adopted the definitions of key terms provided by the trial judge in Carter v. Canada (Attorney General):3

“Physician-assisted death” and “physician-assisted dying” are … generic terms that encompass physician-assisted suicide and voluntary euthanasia that is performed by a medical practitioner or a person acting under the direction of a medical practitioner.

“Physician-assisted suicide” means the act of intentionally killing oneself with the assistance of a medical practitioner, or person acting under the direction of a medical practitioner, who provides the knowledge, means, or both.

“Euthanasia” means the intentional termination of the life of a person, by another person, in order to relieve the first person’s suffering.

“Voluntary euthanasia” means euthanasia performed in accordance with the wishes of a competent individual, whether those wishes have been made known personally or by a valid, written advance directive.

Current practices for medical certificates of death in Canada

Cause of death

Although there is no uniform medical certificate of death in use across Canada, all 12 of the provinces and territories for which we were able to obtain a medical certificate of death ask for the “immediate cause of death” and “antecedent causes, if any, giving rise to the immediate cause …, stating the underlying cause last.” The underlying cause of death is “the cause selected for coding and tabulation of the official cause-of-death statistics.”4 All 12 jurisdictions also ask for “other significant causes contributing to death” but “not causally related to the immediate cause,” “not resulting in the underlying cause” and “not related to the disease or condition causing it.” In addition, all 12 jurisdictions ask for the interval between the onset of each cause or condition and death.

Manner of death

All 12 jurisdictions ask about variations on the “manner of death,” and the respondent must check one from a list of possible answers, including “natural,” “accident,” “homicide,” “suicide,” “pending investigation,” “pending finalized details of natural causes” and “undetermined.” However, not all jurisdictions offer all of these options; for example, only half include “natural.”

For the complete results of our review of medical certificates of death and registrations of death from across Canada, see Appendix 1 (available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.151130/-/DC1). For information about the approaches taken in permissive jurisdictions, see Appendix 2 (available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.151130/-/DC1).

Whether to record physician-assisted death on the death certificate

Medical certificates of death are documents that are used for legal purposes and so should be accurate. For example, they can be used in establishing legal accountability for death or liability for payment on life insurance policies (in terms of both the fact of death and whether any exclusions in the insurance contract were met). Medical certificates of death are used as a source of data for mortality statistics that then inform the allocation of resources, for example, guiding the allocation of health services or health research resources. These documents need to be sufficiently informative to serve that end. Medical certificates of death are also sources of information for a variety of different kinds of research and so should be both accurate and informative. Recording physician-assisted death directly on the medical certificate of death will make end-of-life research (critical for practice and system improvement) much more efficient and reliable. Instead of sampling from all certificates of death and surveying doctors to determine which cases involved physician-assisted death (a model based on the method developed in the Netherlands and Belgium), vital statistics registrars in Canada would be able to provide researchers with all and only the cases of physician-assisted death from the certificates and vital statistics databases. Furthermore, medical certificates of death could be used as a direct tool for the oversight of physician-assisted death. For example, at the end of every year, the vital statistics registrars and the physician-assisted death review committees (assuming such committees are set up) could cross-reference health information documents and forms, including certificates of death, to ensure that all cases of physician-assisted death were reported to the review committees and that these cases were properly recorded on the medical certificates of death. Trust will be essential if physician-assisted death is implemented in Canada, and we believe that transparency on medical certificates of death is part of a solid foundation for trust.

There are, nonetheless, some arguments against recording physician-assisted death on a medical certificate of death (though we find these to be unpersuasive). Doing so might lead insurance companies to deny claims on life insurance policies. The patient might not want anyone to know that he or she died as a result of physician-assisted death. Similarly, the physician might not want anyone to know that he or she participated in physician-assisted death. We consider these concerns below.

Insurance

The concern regarding insurance companies can be set aside, on the following grounds.

The Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association’s position is that life insurance claims in cases of physician-assisted death should not be denied by reason solely of the insured person accessing physician-assisted death, as long as the processes set out in the law for access to physician-assisted death were followed. Therefore, no risk of denial of life insurance coverage would be created by reporting physician-assisted death on the death certificate (Frank Zinatelli, vice president and general counsel, Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association: personal communication, Nov. 18, 2015).

It must be acknowledged here that, in common law, an individual cannot cause a loss and then be compensated for that loss. To allow such compensation requires legislation to override the common law. As a result, provincial and territorial insurance acts now include a provision giving insurers permission to pay out on claims in cases involving suicide. However, these provisions arguably would not cover physician-assisted death (or at least voluntary euthanasia). This, however, is not a reason not to record physician-assisted death on medical certificates of death. Rather, it is a reason to amend the current legislation to allow compensation in all cases of physician-assisted death in which the provisions of future legislation on physician-assisted death have been met.

Privacy

Concerns regarding privacy are real but manageable. First, the cause and manner of death are protected information released to only a small number of people (e.g., legal authorities) and for limited uses (e.g., court cases). Second, the balancing of privacy against the benefits of an accurate and informative accounting of each death is well established in practice. In many circumstances, a patient might wish the cause of death not to be recorded (consider, for example, death caused by a sexually transmitted disease) or a physician might wish the cause of death not to be recorded (consider, for example, deaths due to mishaps during surgery or provision of abortion). Yet physicians are currently required to record these causes of death. There does not seem to be any principled basis for finding a different balance in cases of physician-assisted death. Furthermore, if it were determined that the patient’s or the physician’s name should be protected even more than it already is (i.e., protected from disclosure under a freedom-of-information request), it could be protected pursuant to freedom-of-information and protection-of-privacy legislation. In other words, even if this is a legitimate concern here, it can be met by protecting the information rather than not gathering it.

How to record physician-assisted death on the death certificate

We conclude that physician-assisted death should be required to be recorded on the medical certificate of death. As such, the second question arises: How should physician-assisted death be recorded? It could be recorded in a number of ways: as the manner of death, the cause of death or both. If the cause of death, it could be recorded as the underlying, subsequent antecedent or immediate cause of death.

Manner of death

As noted earlier, all medical certificates of death in Canada currently ask for the manner of death, which reflects how the cause of death came about. For the purposes of completing the medical certificate of death, a “natural” death is brought about by a disease or medical condition. A “non-natural” death is brought about by something other than a disease or medical condition (e.g., homicide, suicide or accident). Thus, in the context of physician-assisted death, the cause of death could be a lethal injection and the manner of death would be unnatural. This suggests that physician-assisted death should be recorded as the manner of death. That is, physician-assisted death should be added to the list of options for manner of death, and it should be broken down into the two subcategories of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide.

Some might suggest that if the recording of physician-assisted death is required on medical certificates of death, the recording of other forms of end-of-life care that can play a contributory or causal role in death (e.g., withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment and terminal sedation [deep and continuous sedation combined with the withholding or withdrawal of hydration and nutrition where death is not imminent]) should also be required. However, there are additional considerations in the context of these other forms of end-of-life care that would have to be taken into account in determining the right balance between the benefits and burdens of compulsory recording (e.g., volume of cases and the fact that loved ones often make decisions about cessation of treatment). Proper consideration of these factors will be necessary for the implementation of a comprehensive regulatory framework for end-of-life care, but this is beyond the scope of the present article.

Cause of death

There are multiple categories of causes of death, running along a temporal spectrum from the antecedent causes (causes giving rise to the immediate cause) to the immediate cause (the final cause in the sequence). The underlying cause is the antecedent cause that initiated the sequence of events leading to death. In other words, the underlying cause starts the chain of events, and the immediate cause is the final link in the chain. Underlying causes may be diseases, other medical conditions or external events (e.g., accidents, intentional acts or errors in medical care). Put another way, the subsequent antecedent causes and the immediate cause both flow from the underlying cause. Some examples may be illuminating. Diabetes mellitus (underlying cause) leads to chronic ischemic heart disease (subsequent antecedent cause), which leads to myocardial infarction (immediate cause). A collision between the car being driven by the patient and a truck (underlying cause) causes a fracture of the vault of the skull (immediate cause). Tripping over a rug at home (underlying cause) causes a fracture of the neck of the femur (subsequent antecedent cause), which leads to terminal hypostatic pneumonia (immediate cause).5

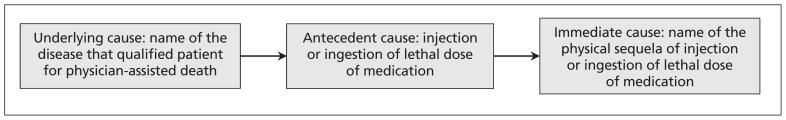

In the context of physician-assisted death and building on well-established practice (and sound logic), the disease or condition that qualified the decedent for physician-assisted death (e.g., pancreatic cancer) starts the chain of events and so should be recorded as the underlying cause of death. The ingestion or injection of a lethal dose of medication should be recorded as the subsequent antecedent cause of death. The physical sequela of the lethal ingestion or injection (e.g., anoxemia) should be recorded as the immediate cause of death (see Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Spectrum of causation of death in the context of physician-assisted death.

Conclusion

From the foregoing, it can be seen that, although some questions will arise from the decriminalization of physician-assisted death for which sui generis answers will be needed, questions about medical certificates of death can and should be answered by reference to and reliance on established principles and practices. It is highly desirable that the approach to medical certificates of death taken in the context of physician-assisted death be harmonized by the vital statistics registrars across all provinces and territories. System oversight and essential end-of-life research will not be possible if each of the various jurisdictions goes its own way.

Key points

Physician-assisted death will likely be legal in Canada in 2016.

Physicians need to know whether and, if so, how to report physician-assisted death on medical certificates of death.

Physician-assisted death should be reported as the manner of death.

The medical condition that qualifies a patient for physician-assisted death should be recorded as the underlying cause of death, the injection or ingestion of a lethal dose of medication should be recorded as the antecedent cause, and the physical sequela of the lethal injection or ingestion should be recorded as the immediate cause.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Brad Abernethy, James Downar and Wanda Morris for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper.

Footnotes

CMAJ Podcasts: author interview at https://soundcloud.com/cmajpodcasts/151130-ana

Competing interests: Jocelyn Downie was a member of the Royal Society of Canada Expert Panel on End-of-Life Decision Making, was a member of the pro bono legal team representing Carter et al. in Carter v. Canada (Attorney General) and is a member of the Provincial–Territorial Expert Advisory Group on Physician-Assisted Dying; the views expressed in this commentary are her own. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Both authors conceived the article, drafted the manuscript, approved the version to be published and agreed to act as guarantors of the work.

References

- 1.An act respecting end-of-life care, RSQ 2014, c S-32.0001. Available: www.canlii.org/en/qc/laws/stat/rsq-c-s-32.0001/latest/rsq-c-s-32.0001.html (accessed 2015 Sept. 13).

- 2.Carter v. Canada (Attorney General), 2015 SCC 5, [2015] 1 S.C.R. 331. Available: https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/14637/index.do (accessed 2015 Sept. 13).

- 3.Carter v. Canada (Attorney General), 2012 BCSC 886 (CanLII). Available: www.canlii.org/en/bc/bcsc/doc/2012/2012bcsc886/2012bcsc886.html (accessed 2015 Nov. 29).

- 4.Instructions for the certifying physician or coroner. In: Medical certificate of death — Form 16. Toronto: Ministry of Consumer and Business Services, Office of the Registrar General; Available: http://s245089275.onlinehome.us/images/Medical_Certificate_of_Death_Form_16.d4cbe05c.pdf (accessed 2015 Nov. 29). [Google Scholar]

- 5.A handbook for physicians and medical examiners: medical certification of death and stillbirth. Halifax: Province of Nova Scotia; 2002. Available: www.novascotia.ca/sns/pdf/ans-vstat-physicians-handbook.pdf (accessed 2015 Nov. 13). [Google Scholar]