Abstract

Background

More than one million patients present to US emergency departments (ED) annually seeking care for acute migraine. Parenteral anti-histamines have long been used in combination with anti-dopaminergics such as metoclopramide to treat acute migraine in the ED. High quality data supporting this practice do not exist. We determined whether administration of diphenhydramine 50mg IV + metoclopramide 10mg IV resulted in greater rates of sustained headache relief than placebo+ metoclopramide 10mg IV.

Methods

This was a randomized, double-blind clinical trial comparing two active treatments for acute migraine in an ED. Eligible patients were adults younger than 65 years presenting with an acute moderate or severe headache meeting International Classification of Headache Disorders-2 migraine criteria. Patients were stratified based on presence or absence of allergic symptoms. The primary outcome was sustained headache relief, defined as achieving a headache level of mild or none within two hours of medication administration, and maintaining this level of relief without use of any additional headache medication for 48 hours. Secondary efficacy outcomes include mean improvement on a 0 to 10 verbal scale between baseline and one hour, the frequency with which subjects indicated they would want the same medication the next time they present to the ED with migraine, and the ED throughput time. Sample size calculation using a 2-sided alpha of 0.05, a beta of 0.20 and a 15% difference between study arms determined the need for 374 patients. An interim analysis was conducted when data were available for 200 subjects.

Results

420 patients were approached for participation. 208 eligible patients consented to participate and were randomized. At the planned interim analysis, the data safety monitoring committee recommended that the study be halted for futility. Baseline characteristics were comparable between the groups. 14% (29/208) of the sample reported allergic symptoms. Of patients randomized to diphenhydramine, 40% (40/100) reported sustained relief at 48 hours, as did 37% (38/103) of patients randomized to placebo (95%CI for difference of 3%: −10, 16%). One hour after medication administration, those randomized to diphenhydramine improved by a mean of 5.1 on the 0 to 10 scale versus 4.8 for those randomized to placebo (95%CI for difference of 0.3: −0.6, 1.1). 85% (84/99) of the patients in the diphenhydramine arm reported they would want the same medication combination during a subsequent ED visit, as did 76% (77/102) of those who received placebo (95%CI for difference of 9%: −2, 20%). Median ED length of stay was 122 minutes (IQR: 84, 180) in the diphenhydramine group and 139 minutes (IQR: 90, 235) in the placebo arm. Rates of side effects, including akathisia, were comparable between the groups.

Conclusions

Intravenous diphenhydramine, when administered as adjuvant therapy with metoclopramide, does not improve migraine outcomes.

Migraine, a recurrent disorder characterized by acute headaches, causes more than one million visits to US emergency departments (EDs) annually.1 Parenteral anti-histamines including diphenhydramine and promethazine are commonly administered to migraine patients in the ED,1 yet high quality data to support efficacy do not exist. Associations among migraine, histamine, and allergy have been reported2. Elevated levels of serum histamine and IgE have been reported in patients with a history of migraine when compared to healthy controls.2 Among patients with a history of migraine, there is greater elevation of histamine levels during an acute migraine than during the inter-ictal period.2 This tends to be more marked among migraine patients with a history of allergy or atopy than those without such a history.2 Prevalence of migraine is higher among those patients with a history of allergic rhinitis than matched controls.3,4 In patients with a history of migraine, an acute headache can be induced by histamine infusion, which can be blocked by co-administration of an antihistamine.5 These data are consistent with the hypothesis that histamine contributes to migraine pathogenesis, particularly among patients who are prone to allergy, and that centrally-acting anti-histamines may be a useful treatment for acute migraine.

Despite the very large number of migraine patients who present to EDs annually, there is substantial variability in treatment.1 More than twenty different parenteral medications or combinations of medications are commonly used to treat acute migraine in this setting, yet the goal of sustained headache relief remains elusive.1,6 When anti-histamines are used to treat acute migraine in the ED, this is usually done as part of a two-drug combination, with the goals of increasing efficacy and decreasing adverse events such as akathisia.1 However, there are no high quality data available to support or refute this practice. Therefore, we conducted a randomized trial to determine the efficacy of co-administering a centrally-acting anti-histamine with standard migraine therapy. Specifically, we wished to test the following hypothesis: In a population of patients presenting to an ED with acute migraine rated as moderate or severe intensity, diphenhydramine 50mg IV + metoclopramide 10mg IV results in greater rates of sustained headache relief than placebo +metoclopramide 10mg IV.

Methods

Study design and setting

This was a randomized, double-blind clinical trial comparing two active treatments for acute migraine. Patients were enrolled upon presentation to the ED, followed for up to two hours in the ED, and then contacted by telephone 48 hours later to determine headache status. This trial was registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01825941). The Albert Einstein College of Medicine IRB provided ethical oversight.

This study was performed in the ED of Montefiore Medical Center, an urban ED that receives 100,000 adult visits annually. Salaried, full-time, bilingual (English and Spanish) technician-level research associates, who gather data for studies under the supervision of the principal investigators, staffed the ED 18–24 hours per day, seven days per week during the study period.

Selection of Participants

Eligible patients were adults younger than 65 years who presented with an acute moderate or severe headache meeting migraine criteria, as defined by the International Classification of Headache Disorders-2 (ICHD-2 1.1, migraine without aura)7. Patients who met criteria for Probable Migraine without Aura (ICHD-2 1.6.1) were also included, provided they had at least one similar headache previously. Status migrainosus, prolonged duration of headache (>72 hours), or early presentation (<4 hours) did not preclude participation. Patients were excluded if informed consent could not be obtained, the attending emergency physician suspected a secondary cause of headache or intended to obtain diagnostic imaging or a lumbar puncture, the maximum documented temperature prior to enrollment was ≥100.4 degrees F, for presence of a new objective neurologic abnormality, or allergy, intolerance, or contra-indication to the study medication. Because all investigational medications used in this study are classified as pregnancy category B and are commonly used for acute migraine in pregnant patients, and because there is a need for evidence-based treatment in pregnant patients, pregnancy did not exclude patients from participation in this study. We required the attending emergency physician’s permission to enroll their patient in this clinical trial.

Interventions

Patients were randomly allocated in a 1:1 ratio to one of the following two interventions:

Metoclopramide 10mg + diphenhydramine 50mg, infused intravenously over 15 minutes

Metoclopramide 10mg + saline placebo, infused intravenously over 15 minutes

To ensure a comparable number of atopic patients in each study arm, patients were stratified by symptoms of allergic nasal congestion as “allergic” or “not allergic”. Allergic symptoms were assessed using the Congestion Quantifier 5 instrument (Appendix).8 Patients were categorized as “allergic” if they scored >6 on this validated instrument.

Randomization was performed by the research pharmacist who generated two sequences (“allergic” and “not allergic”) in blocks of four using computer generated random number tables available at http://www.randomization.com. The pharmacist performed the randomization in a location removed from the ED and inaccessible to ED personnel. In an order determined by these random number tables, the pharmacist inserted medication into identical vials and placed these vials into sequentially numbered identical research bags. These research bags, which were maintained in a locked cabinet in the ED, were then used in a pre-specified order by the research team. Only the pharmacist knew an individual patient’s assignment. Every research bag contained two vials. The metoclopramide vial was as labeled by the manufacturer and contained 2cc of a 10mg/2cc solution of metoclopramide. The other vial was labeled as a research medication and contained 1ml of a clear solution, which consisted of either 50 milligrams of diphenhydramine or saline placebo. After a subject had been enrolled, the two vials from each research bag were placed in a 50cc bag of normal saline by a blinded nurse, which was administered as a slow intravenous drip over 15 minutes.

Methods of measurement

As a primary measure of headache intensity, we utilized a standardized ordinal headache intensity scale, in which subjects describe their headache as “severe”, “moderate”, “mild”, or “none”.9 Other measurement tools included a functional disability scale, in which subjects describe their headache-related disability as severe (“cannot get up from bed or stretcher”), moderate (“great deal of difficulty doing what I usually do and can only do very minor activities”), mild (“little bit of difficulty doing what I usually do”), or none, and an 11-point verbal pain rating scale.10 This latter scale asks subjects to assign their pain a number between 0 and 10, with 0 representing no pain and ten representing the worst pain imaginable. All of these measures are recommended for use in migraine research by the International Headache Society9.

After informed consent was obtained from the patient, a pain assessment was performed. The intravenous solution was then administered as an intravenous drip between time zero and fifteen minutes. Research associates ascertained the patient’s headache level every thirty minutes, and asked a more detailed series of questions regarding pain, functional limitations, and adverse events at one and two hours. If subjects requested more pain medication at or after one hour, they were administered additional medication at the discretion of the treating physician. A final pain assessment was performed by telephone 48 hours after randomization.

At the 48 hour phone call, we also assessed patient satisfaction with the investigational medication they received by asking them, “Would you wish to receive the same medication the next time you visit the ER with migraine?” This question allows patients to summarize succinctly the relative efficacy and tolerability of the medication.

Adverse effects were assessed one, two, and 48 hours after medication administration, using open-ended questions. Two specific, expected adverse effects, drowsiness and restlessness, were both assessed with three-item Likert questions. Acute akathisia, an unpleasant but self-limited reaction characterized by restlessness and anxiety, occurs commonly after administration of intravenous anti-dopaminergics such as metoclopramide. Although instruments have been developed to measure this phenomenon, we have found akathisia difficult to quantify using these instruments because the time of onset of akathisia is variable and typically aborts quickly and completely in response to intravenous therapeutics such as diphenhydramine.11 Therefore, we attempted to capture this phenomenon through the use of other measures: 1) At the time of the 48 hour follow-up, we asked patients if they experienced “restlessness” at any time after receiving the medication. Those who reported that they were “very restless” were considered to have had akathisia. 2) Because diphenhydramine is the rescue medication of choice for akathisia in our ED, we recorded any off-protocol use of parenteral diphenhydramine in all study patients.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was sustained headache relief. As per international criteria, this is defined as achieving a headache level of mild or none within two hours of medication administration, and maintaining that level of mild or none without the use of any additional headache medication for 48 consecutive hours post-treatment.9 Patients who received rescue medication were considered a primary outcome failure.

Secondary efficacy outcomes include the mean improvement in 0 to 10 pain scale between baseline and one hour, the frequency of use of additional anti-headache medication during the ED visit, the frequency of poor functional scores one hour after investigational medication administration, the ED throughput time, defined as time elapsed between medication administration and ED discharge, and the frequency with which subjects indicated they would wish to receive the same medication the next time they presented to the ED with migraine. The frequency of any adverse event was recorded, including the development of akathisia, and the frequency of drowsiness.

Primary Data Analysis

We collected and managed study data using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Albert Einstein College of Medicine. All dichotomous outcomes were reported as frequencies with 95%CI. Absolute risk reduction and number needed to treat were also reported with 95%CI. Improvement in 0 to 10 pain score is reported as mean with 95%CI.

We used the following parameters to calculate the sample size: alpha of 0.05, beta of 0.20, a difference between the groups in the rate of sustained headache relief of 15% (48% in the placebo + metoclopramide arm estimated from prior studies,12 and 63% in the diphenhydramine + metoclopramide arm). This difference of 15% is equivalent to a number needed to treat (NNT) of 6.67, which was chosen as a clinically relevant threshold by polling and averaging the responses of local clinical emergency physicians. Using these assumptions, we determined the need for 344 patients but intended to enroll 374 patients to account for patients lost to follow-up.

A planned interim analysis was conducted after we collected analyzable data on 200 patients. The purpose of the interim analysis was to determine if the study lacked conditional power. The following stopping rule, which was established prior to initiation of the trial, was implemented: If at the interim analysis, which was to take place slightly past the halfway point (200/374 patients), the absolute risk reduction was <7.5% (i.e., < 1/2 of the between-group difference in the sample size calculation), the study was to be halted. Because we did not intend to subject the interim data to a statistical analysis, the alpha of the final analysis was not adjusted.

Results

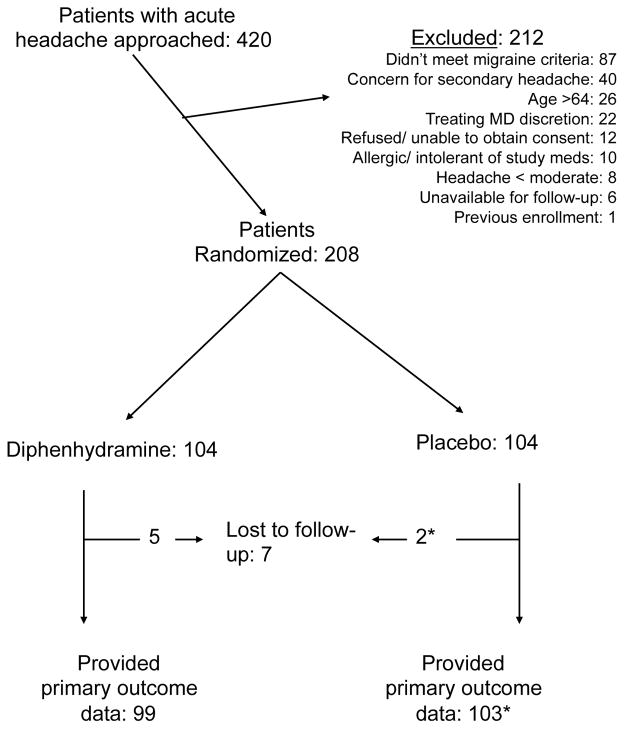

The study commenced in April, 2013 and continued for 21 months. An interim analysis was performed in December, 2014. At that time, the data monitoring committee recommended that the study be halted for futility. During the 21 study months, 420 patients were approached for participation and 208 were randomized (Figure 1). Some attending physicians refused to allow their patients to be enrolled in this trial, usually because they felt uncomfortable administering metoclopramide without diphenhydramine (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics were comparable between the groups (Table 1). Most participants reported severe headache at baseline, though more than 1/3 of our patients had not taken any medication for headache prior to ED presentation (Table 1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram

* One patient lost-to-follow-up received rescue medication in the ED. Therefore, we were able to count this participant as an outcome failure despite being unable to contact her at 48 hours.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Variable | Metoclopramide + diphenhydramine | Metoclopramide + placebo |

|---|---|---|

| Female, n/N(%) | 88/104 (85%) | 92/104 (89%) |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 34 (11) | 36 (10) |

| Used medication for headache prior to ED visit, n/N(%) | 66/104 (64%) | 67/103 (65%) |

| Visual Aura1, n/N(%) | 29/104 (28%) | 39/104 (38%) |

| Sensory Aura2, n/N(%) | 5/104 (5%) | 15/104 (14%) |

| Duration of headache in hours, median (IQR) | 72 (24, 96) | 48 (16, 72) |

| Baseline pain on 0–10 scale, median (IQR) | 9 (8, 10) | 9 (8, 10) |

| Number of functionally impairing headaches over previous 90 days, median (IQR) | 3 (1, 5) | 3 (2, 5) |

| Allergic symptoms3, n/N (%) | 15/104 (14%) | 14/104 (14%) |

Affirmative response to the following question: “Some people have changes in their vision with their headache. BEFORE YOUR HEADACHE BEGAN, did you see things like spots, stars, lights, zig-zag lines or heat waves?”

Affirmative response to the following question: “Some people have changes in their skin sensation with their headache. BEFORE YOUR HEADACHE BEGAN, did you have numbness or tingling in your face or arms?”

Score ≥6 on Congestion Quantifier 5 Instrument (Appendix)

The primary outcome, sustained headache relief, was reported by 40/100 (40%, 95%CI: 31, 50%) patients randomized to diphenhydramine and 38/103 (37%, 95%CI: 28, 47%) of patients randomized to placebo (95%CI for difference of 3%: −10, 16%). Secondary outcomes are reported in Table 2. Despite rates of sustained headache freedom of less than 20% in both arms, more than 3/4rds of patients stated they would want to receive the same medication again (Table 2). Patients randomized to placebo had comparable ED throughput times (median 139 minutes, IQR: 90, 235 minutes) as those who received diphenhydramine (median 122 minutes, IQR: 84, 180 minutes) (p value by Mann-Whitney U was 0.53).

Table 2.

Outcomes among all patients

| Variable | Metoclopramide + diphenhydramine | Metoclopramide + placebo | Difference (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Improvement in 0–10 NRS pain score between baseline and one hour | 5.1 (n=104) | 4.8 (n=101)* | 0.3 (−0.6, 1.1) |

| Required rescue medication in ED | 31/104 (30%) | 40/104 (38%) | 9% (−4, 21%) |

| Sustained headache freedom1 | 17/101 (17%) | 14/102 (14%) | 3% (−7, 13%) |

| Want same med again2 | 84/99 (85%) | 77/102 (76%) | 9% (−2, 20%) |

| Functional impairment at one hour Unable to perform usual activities3 |

27/103 (26%)* | 30/98 (31%)* | 4% (−8, 17%) |

Achieved a headache level of “none” in the ED and maintained a level of “none” without the use of rescue medication for 48 hours. Patients who required rescue medication were considered outcome failures.

At the 48 hour follow-up telephone call patients were asked if they wished to receive the same medication during a subsequent migraine visit to the ED.

Patients who responded “I can’t get out of bed” and “I’d have a great deal of difficulty doing what I usually do” are included in the numerator. Patients who responded “I can do my normal activities” and “I’d have a little bit of difficulty doing what I usually do” are not included in the numerator.

Missing data when patient did not/could not answer the question

Adverse events were comparable between the study arms (Table 3). Patients randomized to placebo did not report greater rates of restlessness nor were they more likely to require rescue doses of diphenhydramine. No patients reported unremitting muscle spasms or tremors.

Table 3.

Adverse events

| Adverse event | Metoclopramide + diphenhydramine n/N (%) | Metoclopramide + placebo n/N (%) | Difference (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Very restless after receiving study meds* | 8/99 (8%) | 7/102 (7%) | 1% (−6, 8%) |

| Required rescue dose of diphenhydramine to treat symptoms of acute akathisia | 5/104 (5%) | 8/103 (8%) | 3% (−4, 10%) |

| Very drowsy after receiving study meds* | 17/99 (17%) | 14/102 (14%) | 3% (−7, 13%) |

At the time of the 48 hour follow-up phone call, study participants were asked to recall if they experienced restlessness or drowsiness after receiving the investigational medication. Participants were forced to choose among the following options: “no,” “a little bit,” “a lot.”

At baseline, fewer than 15% of our patients reported symptoms of allergy, as defined by a score of six or greater on the Congestion Quantifier instrument (Table 4). Among this subset, 7/15 (47%, 95%CI: 25, 70%) patients randomized to diphenhydramine reported sustained relief, as did 8/14 (57%, 95%CI: 33, 79%) patients randomized to placebo (95%CI for difference of 10%: −26, 47%). Among the allergic participants, more patients randomized to diphenhydramine reported satisfaction with the medication received, as reflected by desire to receive the same medication again for a recurrence of migraine (Table 4).

Table 4.

Outcomes among patients deemed allergic

| Variable | Metoclopramide + diphenhydramine | Metoclopramide + placebo | Difference (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Improvement in 0–10 pain score between baseline and one hour | 3.8 (n=15) | 3.7 (n=12)* | 0.1 (−2.1, 2.3) |

| Requirement of Rescue medication | 6/15 (40%) | 3/14 (21%) | 19% (−14, 51%) |

| Sustained headache freedom1 | 3/15 (20%) | 1/13 (8%) | 12% (−13, 37%) |

| Want same med again2 | 14/15 (93%) | 7/13 (54%) | 39% (10, 69%) |

2 patients did not provide an answer to this question

Achieved a headache level of “none” in the ED and maintained a level of “none” without the use of rescue medication for 48 hours. Patients who required rescue medication were considered outcome failures.

At the 48 hour follow-up telephone call patients were asked if they wished to receive the same medication during a subsequent migraine visit to the ED.

Limitations

This study was conducted in one urban ED serving a predominantly socio-economically depressed population. The impact of socio-economics on our study population is apparent in some of the data, such as the high frequency with which patients presented to the ED without having taken any medication for their migraine (Table 1).

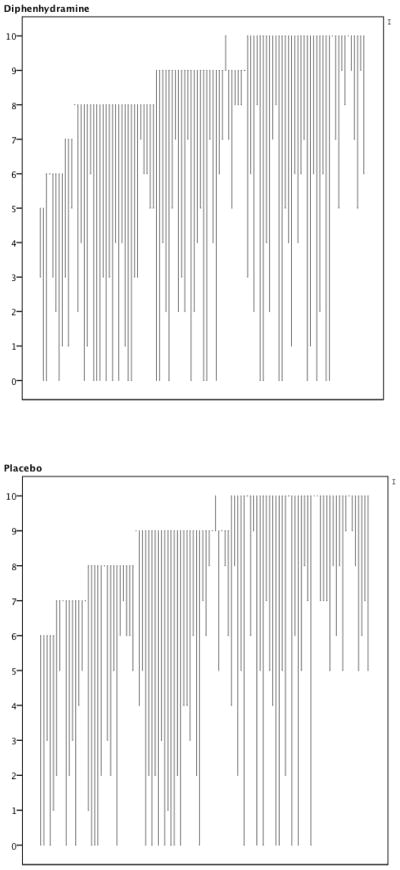

When powering the study, we determined our hypothesized effect size by polling and averaging the responses of local emergency physicians as we were unable to identify an evidence-based minimum clinically significant decrease for our primary outcome (sustained headache relief). Therefore, an important assumption of our design may not reflect the widespread opinion of practicing emergency physicians. Specifically, we needed to observe an absolute 15% increase in the proportion of patients with headache relief at 48 hours; since other emergency physicians and patients might be satisfied with less efficacious treatments, the current trial only addresses adjuvant diphenhydramine lacking a large effect. As such, our findings may have less generalizability to some patients and clinicians. As with all clinical studies, individual physicians should interpret our data in context of which outcome and number needed to treat is most relevant for them and their individual patient—for example, some clinicians may see that 85% of participants who received diphenhydramine would want the same medication combination during a subsequent ED visit while only 76% of those who received placebo would want the same medication combination again. The changes in pain score from baseline to 1-hour are depicted by group and individually in the figure.

Outcome measures in the allergic sub-group were less encouraging about the potential for smaller, but plausibly important effects. Symptoms of allergy at baseline were relatively uncommon in this cohort. Fewer than 15% of all study participants were rated as allergic using a validated instrument. This limits our ability to comment on the efficacy of diphenhydramine within this population. Our data do not preclude the possibility of benefit, particularly because more patients who received diphenhydramine would want the same medication combination during a subsequent migraine attack. However, the point estimate of the primary outcome favored placebo, as did need for rescue medication. The improvement in 0 to 10 pain score between baseline and one hour was comparable.

Based on a stopping rule established before this study began, the study monitoring committee recommended halting the study after 208 patients were enrolled, slightly past the halfway point of the trial. It is possible that the findings in the first half of the sample were not representative and continued data collection would have revealed a clinically significant difference between groups but that is extremely unlikely given the large size of the interim sample and the small difference between groups.

Discussion

In this ED-based, double-blind, randomized clinical trial of treatment for acute migraine, we found that adding 50mg of intravenous diphenhydramine to metoclopramide 10mg did not improve outcomes when compared to metoclopramide alone. Diphenhydramine also did not decrease the rate of akathisia. Our results are generally in keeping with other ED-based acute migraine clinical trials, which have shown that although substantial initial relief is generally obtainable regardless of which parenteral intervention is used, sustained relief for 48 hours beyond the ED visit is more difficult to achieve.12–17

Given the frequency with which anti-histamines are used to treat acute migraine, there is a surprising paucity of experimental data on this topic. Existing data comes from small clinical trials18 or non-experimental designs,19 which have reached different conclusions. To our knowledge, this is the first adequately powered randomized clinical trial to demonstrate that diphenhydramine does not improve outcomes in an unselected population of ED patients presenting with acute moderate to severe migraine.

Theories of an allergic basis of migraine date back nearly 100 years20,21. Food allergy in particular has been linked to migraine and food elimination diets have purportedly cured migraine.22 Experimentally designed studies have reached differing conclusions, but suggest that targeted food elimination diets may be of mild to modest benefit for selected allergic migraine patients. 23,24,25,26 Among our migraine patients with concomitant symptoms of allergic rhinitis, diphenhydramine did not appear to confer any benefit over metoclopramide alone.

Diphenhydramine is often given prophylactically to blunt extra-pyramidal side effects (mostly akathisia) of intravenous anti-dopaminergics. While this is an evidence-based strategy for patients given intravenous prochlorperazine,10,27 existing data do not support the use of diphenhydramine in this role for patients given intravenous metoclopramide.11,28 Similarly, in this study, the rate of akathisia was comparable regardless of whether patients received 50mg intravenous diphenhydramine or placebo. While only 8% of patients who received metoclopramide + placebo experienced akathisia, this is frequent enough that physicians should caution patients that this side effect may occur with this medication.

Other extra-pyramidal side effects were uncommon. As far as we could determine using structured telephone follow-up at 48 hours, there were no occurrences of other dystonic reactions or tardive dyskinesia in either study arm. Tardive dyskinesia in particular is a rare extra-pyramidal side effect, typically associated with longer exposure to anti-dopaminergic agents. Nonetheless, this study of only 208 patients is ill-suited to comment on the incidence of this rare irreversible motor disorder. To the best of our knowledge, tardive dyskinesia has never occurred after a single dose of intravenous metoclopramide.29

We were somewhat surprised to discover that length of stay in the ED was not greater among those patients who received 50mg of intravenous diphenhydramine. Drowsiness is a known side effect of diphenhydramine. It is therefore unclear why study participants who received diphenhydramine did not have longer ED dwell times or report more functional impairment at two hours than those allocated to placebo. Our findings, however, are consistent with other studies of centrally-acting anti-dopaminergics combined with diphenhydramine, in which drowsiness or functional impairment at the time of ED discharge among those who received the centrally acting agents was no greater than among those who received sumatriptan, a medication not expected to cause drowsiness.13,30

In conclusion, there is no reason to co-administer intravenous diphenhydramine with metoclopramide routinely for ED patients with acute migraine.

Acknowledgments

This publication was supported in part by the CTSA Grant UL1 TR001073, TL1 TR001072, KL2 TR001071 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Appendix. Congestion Quantifier 5 Instrument8

During the past week, how often….

Did you have nasal stuffiness, blockage or congestion

Did you have to breathe through your mouth because you couldn’t breathe through your nose

Did you have difficulty completely clearing your nose even after repeated blowing

Did you awaken in the morning with nasal stuffiness, blockage, or congestion

How often was your sleep affected by nasal stuffiness, blockage, or congestion

None of the time=0

A little of the time=1

Some of the time=2

Most of the time=3

All of the time=4

Score of ≥6= positive

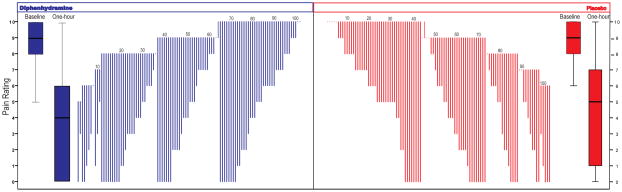

Figure. Group and individual change in pain scores following treatment with metoclopramide plus either placebo or diphenhydramine.

The box plots show the median, 25th and 75th percentiles for the baseline pain score and the pain score measured one hour after treatment for each of the groups. The waterfall plots show the individual change in pain score for subjects in each group from baseline to one hour grouped by baseline pain score, (dots indicate no change, lines going above baseline indicate a worsening). The numbers above the waterfall plot are given to indicate every 10 patients.

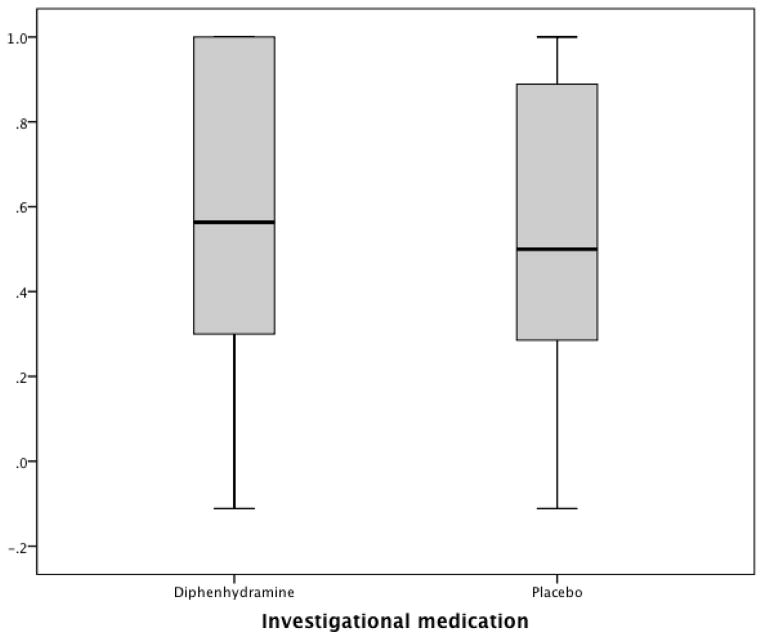

Appendix Figure.

Box and whiskers plot of the percent improvement in 0 to 10 pain score between baseline and one hour (Improvement in 0–10 score/Baseline score). 1.0 signifies complete improvement. 0 signifies no improvement. Negative score indicate worsening.

Appendix Figure.

Line graph representing each participant’s experience at baseline and one hour later. The origin of the line depicts the 0 to 10 pain score at baseline. The terminus of the line depicts the 0 to 10 pain score at one hour. The graphs are sorted by baseline pain score. Thus, lines that rise unexpectedly depict participants whose pain worsened during the study period.

Footnotes

We will present this study at the American Headache Society national meeting in Washington DC on 6/20/2015

We have no conflicts of interest to report.

BWF, CS, DE, PEB, EJG conceived the study and designed the trial. BWF, DE supervised the conduct of the trial and data collection. BWF, LC, VA managed the data, including quality control. BWF analyzed the data; PEB chaired the data oversight committee. BWF drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed substantially to its revision. BWF takes responsibility for the paper as a whole.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Friedman BW, West J, Vinson DR, Minen MT, Restivo A, Gallagher EJ. Current management of migraine in US emergency departments: An analysis of the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Cephalalgia. 2014 doi: 10.1177/0333102414539055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gazerani P, Pourpak Z, Ahmadiani A, Hemmati A, Kazemnejad A. A Correlation between Migraine, Histamine and Immunoglobulin E. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;2:17–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aamodt AH, Stovner LJ, Langhammer A, Hagen K, Zwart JA. Is headache related to asthma, hay fever, and chronic bronchitis? The Head-HUNT Study. Headache. 2007;47:204–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ku M, Silverman B, Prifti N, Ying W, Persaud Y, Schneider A. Prevalence of migraine headaches in patients with allergic rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97:226–30. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60018-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta S, Nahas SJ, Peterlin BL. Chemical mediators of migraine: preclinical and clinical observations. Headache. 2011;51:1029–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01929.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman BW, Bijur PE, Lipton RB. Standardizing emergency department-based migraine research: an analysis of commonly used clinical trial outcome measures. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:72–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00587.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. Cephalalgia. 1988;8(Suppl 7):1–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stull DE, Meltzer EO, Krouse JH, et al. The congestion quantifier five-item test for nasal congestion: refinement of the congestion quantifier seven-item test. American journal of rhinology & allergy. 2010;24:34–8. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2010.24.3394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tfelt-Hansen P, Block G, Dahlof C, et al. Guidelines for controlled trials of drugs in migraine: second edition. Cephalalgia. 2000;20:765–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2000.00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vinson DR. Diphenhydramine in the treatment of akathisia induced by prochlorperazine. J Emerg Med. 2004;26:265–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman BW, Bender B, Davitt M, et al. A randomized trial of diphenhydramine as prophylaxis against metoclopramide-induced akathisia in nauseated emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:379–85. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedman BW, Mulvey L, Esses D, et al. Metoclopramide for acute migraine: a dose-finding randomized clinical trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57:475–82. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.11.023. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedman BW, Corbo J, Lipton RB, et al. A trial of metoclopramide vs sumatriptan for the emergency department treatment of migraines. Neurology. 2005;64:463–8. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000150904.28131.DD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman BW, Esses D, Solorzano C, et al. A randomized controlled trial of prochlorperazine versus metoclopramide for treatment of acute migraine. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman BW, Garber L, Yoon A, et al. Randomized trial of IV valproate vs metoclopramide vs ketorolac for acute migraine. Neurology. 2014;82:976–83. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman BW, Greenwald P, Bania TC, et al. Randomized trial of IV dexamethasone for acute migraine in the emergency department. Neurology. 2007;69:2038–44. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000281105.78936.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedman BW, Solorzano C, Esses D, et al. Treating headache recurrence after emergency department discharge: a randomized controlled trial of naproxen versus sumatriptan. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:7–17. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tek D, Mellon M. The effectiveness of nalbuphine and hydroxyzine for the emergency treatment of severe headache. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16:308–13. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(87)80177-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swidan SZ, Lake AE, 3rd, Saper JR. Efficacy of intravenous diphenhydramine versus intravenous DHE-45 in the treatment of severe migraine headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2005;9:65–70. doi: 10.1007/s11916-005-0077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richards MH, Balyeat RM. The Inheritance of Allergy with Special Reference to Migraine. Genetics. 1933;18:129–47. doi: 10.1093/genetics/18.2.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rowe AH. Allergic Toxemia and Migraine Due to Food Allergy: Report of Cases. California and western medicine. 1930;33:785–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walker VB. The Place of Allergy in Migraine. The Journal of the College of General Practitioners. 1963;6(SUPPL4):21–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchell N, Hewitt CE, Jayakody S, et al. Randomised controlled trial of food elimination diet based on IgG antibodies for the prevention of migraine like headaches. Nutrition journal. 2011;10:85. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-10-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alpay K, Ertas M, Orhan EK, Ustay DK, Lieners C, Baykan B. Diet restriction in migraine, based on IgG against foods: a clinical double-blind, randomised, cross-over trial. Cephalalgia. 2010;30:829–37. doi: 10.1177/0333102410361404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aydinlar EI, Dikmen PY, Tiftikci A, et al. IgG-based elimination diet in migraine plus irritable bowel syndrome. Headache. 2013;53:514–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2012.02296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mansfield LE, Vaughan TR, Waller SF, Haverly RW, Ting S. Food allergy and adult migraine: double-blind and mediator confirmation of an allergic etiology. Annals of allergy. 1985;55:126–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vinson DR, Drotts DL. Diphenhydramine for the prevention of akathisia induced by prochlorperazine: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37:125–31. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.113032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erdur B, Tura P, Aydin B, et al. A trial of midazolam vs diphenhydramine in prophylaxis of metoclopramide-induced akathisia. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Friedman BW, Garber L, Gallagher EJ. Author response. Neurology. 2014;83:1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kostic MA, Gutierrez FJ, Rieg TS, Moore TS, Gendron RT. A prospective, randomized trial of intravenous prochlorperazine versus subcutaneous sumatriptan in acute migraine therapy in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]