Abstract

Degenerative rotator cuff disease is commonly associated with ageing and is often asymptomatic. The factors related to tear progression and pain development are just now being defined through longitudinal natural history studies. The majority of studies that follow conservatively treated painful cuff tears or asymptomatic tears that are monitored at regular intervals show slow progression of tear enlargement and muscle degeneration over time. These studies have highlighted greater risks for disease progression for certain variables, such as the presence of a full-thickness tear and involvement of the anterior aspect supraspinatus tendon. Coupling the knowledge of the natural history of degenerative cuff tear progression with variables associated with greater likelihood of successful tendon healing following surgery will allow better refinement of surgical indications for rotator cuff disease. In addition, natural history studies may better define the risks of nonoperative treatment over time. This article will review pertinent literature regarding degenerative rotator cuff disease with emphasis on variables important to defining appropriate initial treatments and refining surgical indications.

Introduction

Rotator cuff disease is prevalent in the aging population and is the most common cause of shoulder disability. There is considerable controversy among orthopaedic surgeons on the optimal management of rotator cuff disease and clinicians have significant variation in their management of cuff tears1. Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) set out by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) on rotator cuff disease demonstrate a lack of high-quality evidence available to help guide treatment of patients with cuff pathology. The work group involved in constructing the CPGs suggested the need to better understand the epidemiology and demographics of natural history of rotator cuff disease. By studying the natural history, we can better understand risk factors for tear deterioration and the progression of irreversible muscle changes with time. Through natural history studies, tears with higher risk of disease progression can be identified, allowing for further refinement of surgical indications and a better understanding of the risks of non-operative treatment.

Epidemiology of Rotator Cuff Disease

Both cadaveric2–6 and in vivo imaging studies7–15 have been used to define the prevalence of rotator cuff disease. Because of significant difference in population characteristics and designs of these studies, the reported prevalence in the general population varies widely. Consistent across studies is the finding that increasing age is associated with increased prevalence of rotator cuff pathology5, 6, 10, 12, 13. Yamaguchi et al performed bilateral shoulder ultrasounds on patients presenting with unilateral shoulder pain12 demonstrating an incremental increase in cuff tearing with age. The average age of patients with bilaterally intact cuffs, unilateral cuff tears, and bilateral cuff tears demonstrated an almost perfect ten year distribution and was 48.7, 58.7, and 67.8 years, respectively. In patients with a cuff tear on the symptomatic side, there was a 50% chance of the patient having a cuff tear on the asymptomatic side at 66 years of age or older. A more recent population-based study supported this finding13 – a quarter of patients above 60 years of age and one half of patients above 80 years of age were found to have a rotator cuff tear. These and other studies14, 15 suggest that tendon degeneration occurs with aging.

While most would agree that rotator cuff disease is multifactorial and includes biologic and mechanical influences, recent studies have also suggested a strong genetic influence on disease development16–18. Tashjian et al utilized the Utah Population Database to analyze potential heritable predisposition to rotator cuff disease and found significantly elevated risks in first and second-degree relatives of patients with rotator cuff disease17. Harvie et al performed ultrasounds in siblings of over 200 patients with full-thickness cuff tears16. Using the subjects’ spouse as a control group, there was a significantly increased risk for rotator cuff tears in siblings of patients. A subsequent study by the same group implied that genetic factors may have a role in the progression of tears as well18.

Another consistent finding throughout the literature is the relatively high prevalence of asymptomatic tears7, 10–12, 14, 19–21. Because these patients have no pain, have acceptable shoulder function, and do not require any treatment for their tears, prospective evaluation of these shoulders has provided us with a wealth of information regarding the natural history of rotator cuff disease.

Traumatic versus Degenerative Rotator Cuff Tears

Evaluation of a patient should attempt to differentiate traumatic from degenerative, attritional rotator cuff tears. Although the supporting literature is limited to case series22–25, it is generally recommended to perform an early repair for acute, traumatic rotator cuff tears, particularly in young individuals, in order to optimize the tissue quality and healing environment, as well as to prevent tear retraction and fatty degeneration of the involved muscle. Bassett and Cofield studied 37 patients that had rotator cuff repair within three months of injury and divided them into groups that had surgery within three weeks, between three and six weeks, and between six and 12 weeks22. Those that underwent repair within three weeks had the best functional results. The threshold of the timing for “optimal” results of acute cuff tears has ranged anywhere from 3 weeks22–24 to 4 months25.

Treatment of atraumatic degenerative rotator cuff tears that occur with advancing age is more controversial. Many factors including patient age, tear size, tendon retraction, muscle degeneration, and overall healing capacity must be taken into account. Study of the natural history of degenerative tears can elucidate the risk factors for tear progression and irreversible changes and can help clinicians make evidence based decisions regarding management of these tears.

Study of the Natural History of Rotator Cuff Disease through Asymptomatic Tears

Attempting to define the natural history of rotator cuff disease of painful cuff tears is not ideal, as treatment may interrupt or influence the disease progression. Painful tears are often treated with physiotherapy, injections, or surgery, any of which may disrupt the true natural history of disease progression. An ideal cohort for defining the risks of tear enlargement and progression of muscle degeneration are asymptomatic degenerative cuff tears that can be identified early and followed longitudinally. As cuff disease if often bilateral, screening subjects with unilateral painful cuff disease on presentation can identify a large number of asymptomatic tears12. Additionally, patients with unilateral symptomatic rotator cuff tears have been shown to be “at risk” for pain development and tear progression on the asymptomatic side20, 26.

Tear Initiation and Location

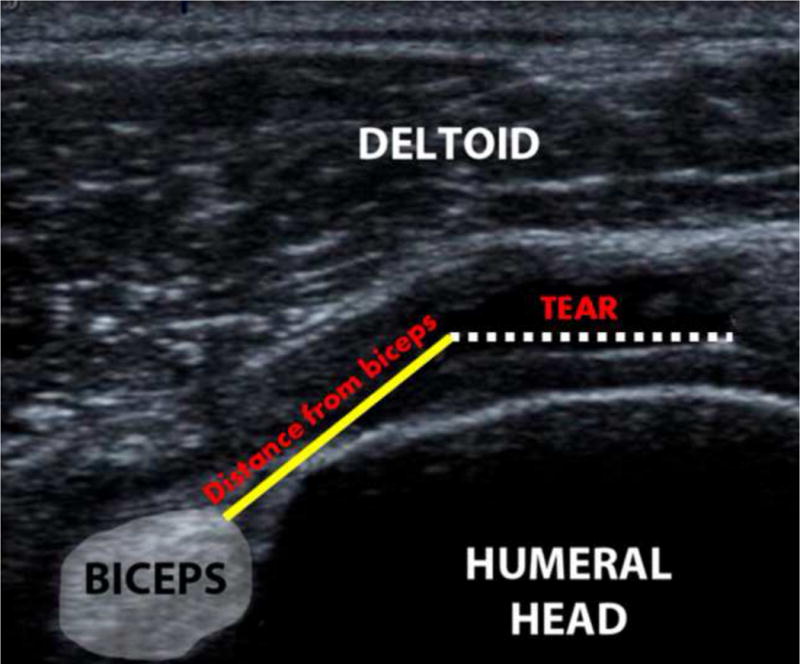

Understanding the common locations and site of initiation of degenerative rotator cuff tears is essential to describing the pathogenesis of the disease. Early theories on tear initiation reported the common location of degenerative tears was the articular aspect of the anterior supraspinatus adjacent to the biceps tendon2, 27, 28. Tears were felt to then propagate posteriorly into the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons. This conventional theory has been challenged with recent research. Kim et al mapped the common locations of degenerative cuff tears with ultrasound by measuring the distance from the anterior tear edge to the biceps tendon and then factoring in the size (sagittal plane width) of the tear (Figure 1)29. Analyzing data from 272 patients, histograms were generated plotting the frequency of tear involvement within the cuff footprint at each millimeter distance posterior from the biceps tendon. When analyzing full-thickness tears, the area around 13 to 17 millimeters posterior the biceps tendon was most frequently involved, with only 30% of tears involving the most anterior aspect of the supraspinatus. In addition, when looking at only small full-thickness tears, a similar distribution was found with the highest frequency located 15 millimeters posterior to the biceps. The similarity in tear location of full-thickness tears of various sizes suggest the common location of tear initiation for degenerative cuff tears to lie within the rotator crescent, usually sparing the anterior cable attachment of the supraspinatus tendon.

Figure 1.

Ultrasound can be utilized to measure the distance from the posterior biceps to the anterior border of the rotator cuff tear.

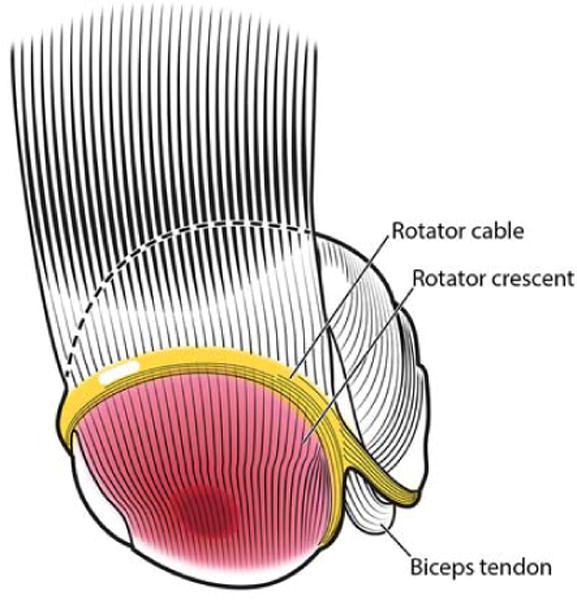

This finding had a number of implications based on the anatomy of the rotator cuff. First, the area 15 mm posterior to the biceps tendon lies either at the junction of the supraspinatus and the infraspinatus or predominantly within the anterior infraspinatus, depending on which anatomical definition is used30, 31. Second, this area correlates to the middle of the “rotator crescent” tissue as described by Burkhart32 (Figure 2). As opposed to the “rotator cable” which is a thicker band of rotator cuff tissue spanning from the anterior supraspinatus to the posterior infraspinatus, the crescent tissue is thinner, more avascular tissue lateral to the cable. This crescent tissue is typically shielded from stress due to the “suspension bridge” configuration of the cable. This data would suggest that rotator cuff tears initiate towards the middle of this crescent tissue and likely propagate anteriorly and posteriorly from that point.

Figure 2.

Rotator cuff tears initiate approximately 15 millimeters posterior to biceps tendon within the rotator crescent tissue.

Tear Characteristics and Muscle Degeneration

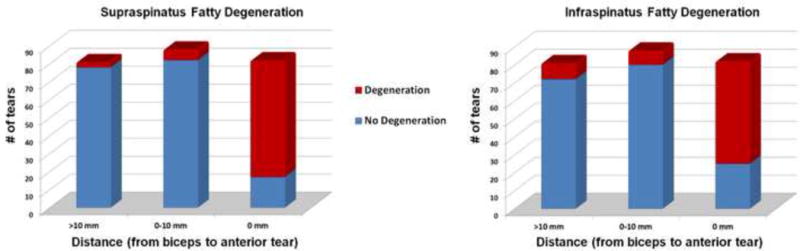

Muscle degeneration has important prognostic consideration for patients undergoing rotator cuff repair surgery as advanced degeneration has been linked to lower rates of tendon healing33, 34. Based on the suspension bridge concept, the anterior portion of the supraspinatus is a critical area of tissue for distribution of forces along the cable. Disruption of the anterior cable may lead to accelerated retraction and muscle degeneration. Kim et al used similar methods to the study on tear initiation to quantify the importance of the anterior supraspinatus tissue35. Ultrasound was used to measure tear location referenced to the biceps tendon and tear size compared to the degree of fatty degeneration of the cuff muscles. Both tear size and tear location were associated with patterns of fatty muscle degeneration. Tears with disruption of the anterior supraspinatus tendon demonstrated more advanced degeneration of the supraspinatus tendon. Infraspinatus degeneration was more closely linked to the sagittal plane size of the tear. Larger tears with propagation into the infraspinatus footprint were more likely to have both supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscle degeneration, especially when the anterior supraspinatus tendon was compromised (Figure 3). This data stresses the importance of anterior supraspinatus tissue integrity. Patients with cuff tears close to the anterior margin of the supraspinatus should be counseled that they possess a higher risk of tendon retraction and muscle atrophy. Closer surveillance of these tears may be warranted when treated non-operatively.

Figure 3.

Association between location of tear (distance from biceps to anterior margin of tear) and rotator cuff fatty degeneration.

Tear Size and Glenohumeral Kinematics

As rotator cuff tears increase in size, disruption of normal glenohumeral kinematics can occur. This may manifest as proximal humeral migration. The effect of rotator cuff size on glenohumeral kinematics and proximal humeral migration was investigated by Keener et al36 using a computer based calculation of the humeral head center in relation to the glenoid center. A cohort of 98 asymptomatic and 62 symptomatic full-thickness tears were examined. Symptomatic tears and larger tears involving the infraspinatus had more migration than tears in asymptomatic patients and smaller tears isolated to the supraspinatus. A critical tear area of 175 mm2 was associated with proximal humeral migration correlating with a tear size of approximately 15 mm with retraction of 12–15 mm. These findings highlight the importance of the infraspinatus in maintaining normal coronal plane kinematics as noted by previous basic science research37–39.

Tear Enlargement and Pain Development of Asymptomatic Tears

Perhaps the most valuable aspect of studying asymptomatic rotator cuff tears longitudinally is defining the risks of tear progression and pain development over time. Characterizing the risks of pain development, tear enlargement, and muscle degeneration can help us refine surgical indications and counsel patients regarding the risk of non-operative treatment. This requires long-term prospective studies following these asymptomatic tears14, 20, 26

Moosmayer followed 50 patients with asymptomatic tears over three year period20. Eighteen of fifty tears (36%) developed symptoms, and tear progression was significantly larger in the symptomatic than the asymptomatic group. Progression of muscle atrophy and fatty degeneration was also higher in the symptomatic group than the asymptomatic group. This study demonstrated an association between symptom development and increasing tear size. These results are consistent with the findings of Mall et al who investigated variables associated with pain development in asymptomatic tears26, also noting pain development in patients with asymptomatic tears was associated with tear progression.

A subsequent report of this cohort has better defined the risks of tear progression and pain development for a period of 5 years after identification of an asymptomatic degenerative tear40. A total of 224 patients with 118 full-thickness, 56 partial-thickness, and 50 controls were followed longitudinally for a median of 5.1 years. Tear enlargement occurred in a time dependent manner with greater risks of enlargement seen in more severe tear types. Tear progression/enlargement was seen in 49% of shoulders with a median time to enlargement of 2.8 years. Full-thickness tears were 1.5 and 4 times more likely to enlarge compared to partial-tears and control shoulders. Likewise, muscle degeneration was more frequent in full-thickness tears and those tears that progressed in size. Forty-six percent of shoulders developed new pain and the median time to pain development was 2.6 years. Tear enlargement was a significant risk factor for pain development. Thirty-eight percent of shoulders that remained asymptomatic enlarged compared to 63% of shoulders that developed pain. More severe tear types (full vs. partial) also had a greater risk for future pain development. The findings from this study support the progressive nature of degenerative rotator cuff disease and highlight full-thickness tears to be a higher risk group for future tear enlargement, progression of muscle degeneration and pain development.

Natural History of Symptomatic Rotator Cuff Tears

Currently, there are few studies that have evaluated the natural history of symptomatic rotator cuff tears41–43. Maman et al retrospectively studied 59 shoulders with full- and partial-thickness rotator cuff tears treated non-operatively43. Each shoulder had a baseline MRI and a repeat imaging performed a minimum of 6 months later. Progression of tear size was found in 48% of the tears that were followed at least 18 months versus only 19% of those followed less than 18 months. Full-thickness tears were more likely to progress than partial-thickness tears (52% vs. 8%). Age was an important predictor of tear deterioration with 54% of tears in patients over 60 progressing versus only 17% of tears in patients under 60 years. Safran specifically investigated a cohort of patients under 60 years of age that were treated non-operatively for full-thickness rotator cuff tears and found a higher rate of tear progression in these younger patients42. Of the 61 tears, 49% of tears increased in size by ultrasound. There was a significant correlation between pain and increase in tear size.

Fucentese et al reported seemingly contradictory findings in their report of 24 patients refusing operative treatment for full-thickness supraspinatus tears41. They utilized MR arthrography as their initial imaging modality and MR without arthrography for their follow-up imaging and reported no increase in the mean size of the rotator cuff tears 3.5 years after the initial MR arthrogram. While the mean tear size did not increase, eight of the 24 patients (33%) had an increase in tear size, and four (17%) had no change in size. They do report a high level of satisfaction in this group of patients treated non-operatively.

The Multicenter Orthopaedic Outcomes Network (MOON) Shoulder Group has also provided valuable information in the non-operative treatment of symptomatic rotator cuff tears44–47. This group has done multiple observational and cross-sectional studies on more than 400 patients with atraumatic, full thickness rotator cuff tears. They have found that pain and duration of symptoms are not strongly associated with the severity of rotator cuff tears45, 48 and that non-operative management with physical therapy is effective in treating 75% of patients up to two years46. Interestingly, the most important factor for predicting a successful response to conservative treatment from this study was the patients’ perception that physical therapy would be beneficial.

The association of pain with full-thickness rotator cuff tears is controversial. Studies by the MOON Shoulder Group suggest that pain and duration of symptoms do not correlate with the severity of rotator cuff tears45,48, while other studies have shown stronger correlations between enlargement of tears and development of pain20,26. These differences are likely attributed to differences in study design (cross sectional versus prospective observational). More data, other than tear size progression, may identify factors causally related to the onset of pain.

Important Clinical and Radiographic Variables

When evaluating a patient with a suspected degenerative rotator cuff tear, a comprehensive history is the first and arguably the most important aspect of a complex decision making process. The patient’s age is thought to be a strong predictor of rotator cuff healing if operative intervention is considered – older patients are less likely to have a durable repair. Time since initiation of symptoms is important to estimate the chronicity of the tear. While influencing other factors, such as tear size and location, chronicity likely has an undefined impact on healing potential. Activity expectations must be taken into consideration – a patient without high functional demands may retain good function with a full thickness rotator cuff tear. On the other hand, a small full thickness rotator cuff tear may present difficulties to a young laborer who requires overhead motion and strength. Genetic pre-disposition, hand-dominance, smoking, medical co-morbidities, and social factors affecting postoperative rehabilitation potential are other variables that should also be taken into consideration. Prior treatments such as physical therapy, injections, and previous surgery should be documented.

Physical examination is performed with the shoulder exposed. Atrophy of the spinati fossa can be visually distinct in chronic cuff tears (Figure 4). The examiner will often note subacromial crepitus with rotation. Both passive and active range of motion should be documented to rule out restrictions in motion due to arthritic conditions or adhesive capsulitis. Internal rotation behind the back may be limited due to pain in patients with active cuff inflammation. Signs of subacromial impingement can identify patients with cuff-based pain. A careful examination for signs of cervical radiculopathy should be performed especially in patients with medial scapula pain or symptoms radiating below the elbow.

Figure 4.

Atrophy of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus fossas can be visible in chronic tears.

Strength testing can isolate each of the four rotator cuff muscles. Resistance to abduction with the thumb down can test the supraspinatus. External rotation with the arm at the side can test infraspinatus strength while an external rotation lag sign and the Hornblower’s sign can indicate posterior tear extension into the teres minor. The abdominal compression test can test subscapularis function. The lift-off test can also test subscapularis function but is often restricted by pain in patients with tears of the superior cuff. External rotation and/or abduction weakness out of proportion to the severity of a cuff tear may be secondary to pain but also may signal a suprascapular nerve injury. Consideration for electromyographic/nerve conduction studies should be entertained in these select cases.

Imaging should begin with plain radiographs including AP, true AP (Grashey view) in 30 degrees of abduction, scapular Y, and axillary views. The Grashey view activates the deltoid muscle allowing proximal humeral migration in chronic, larger tears (Figure 5). The scapular Y view can assess acromial spurs associated with cuff tears that may need to be addressed at the time of surgery49. The axillary view will demonstrate joint space narrowing as well as potential anterior or posterior humeral subluxation.

Figure 5.

Proximal humeral migration is best viewed on a true AP radiograph with the arm in 30 degrees of abduction.

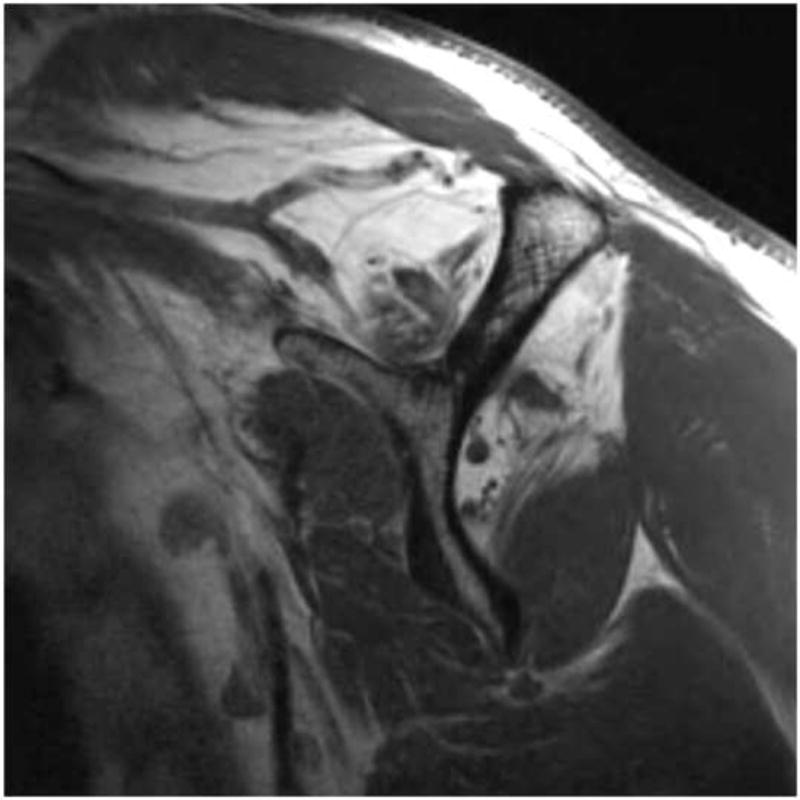

Advanced imaging modalities including ultrasound and MRI should be used when a rotator cuff disease is suspected by history and exam. These modalities can be used to further characterize the size, location, and retraction of rotator cuff tears. The presence or absence of muscle atrophy should be documented in full-thickness tears (Figure 6) and graded according to the Goutallier classification50. Concomitant pathology to other structures such as the long head of the biceps, labrum and early glenoid and humeral chondrosis should be assessed.

Figure 6.

Fatty muscle degeneration of the rotator cuff muscle bellies is best visualized on MRI with T1 oblique sagittal cuts.

Clinical Decision Making

Our understanding of the natural history of rotator cuff disease continues to improve and assist clinicians in an often complex decision making process. As we continue to learn more, our indications for operative repair will continue to be refined. Surgical indications may be simplified by dividing cuff tears into 3 categories where the risks for nonoperative treatment may vary significantly and the potential benefits of surgery may be maximized.

Group I – Early operative repair. Early surgery should be considered in patients presenting with a rotator cuff tear stemming from a distinct, acute event with imaging that corroborates an acute injury. Pain or weakness before injury and signs of muscle degeneration on imaging may be signs of an acute-on-chronic tear. In these situations, an injury resulting in a significant increase in shoulder weakness likely represents a significant acute component to the tear. Consideration for early surgery should be given in these scenarios if the imaging tests do not suggest severe muscle atrophy. Early repair should be performed in acute subscapularis tears or more chronic subscapularis tears with biceps tendon instability. Acute, retracted subscapularis tears are considered more urgent due to the potential for fixed retraction and muscle degeneration that can accompany these injuries. Early operative repair should also be considered in small to medium sized full-thickness degenerative tears in younger patients under the age of 62–65 with minimal or no muscle atrophy; however, specific patient characteristics should be used to refine which patients should be indicated for repair. The reason to consider early surgery in these scenarios relates to the established risks for the potential for tear enlargement and progression of muscle atrophy in patients who still possess a reasonable potential to heal a surgical repair. Due to the fact that loss of anterior supraspinatus tissue integrity is associated with muscle degeneration, early surgical intervention or close surveillance should be employed in patients that have tears involving the anterior supraspinatus tendon.

Group II – Trial of conservative treatment. Initial non-operative treatment is reasonable in any patient with a painful partial thickness tear or a potentially reparable full-thickness tear that is not acute in onset. In these cases, conservative treatment has been shown to produce reliable results in the short-term and some signs of tear chronicity are often already evident. Although risks for tear enlargement and muscle atrophy progression are present, the natural history studies suggest that these changes occur slowly allowing for adequate time to attempt conservative treatment. Surgery can be considered if conservative treatment fails.

Group III – Maximize conservative treatment. Conservative treatment should be maximized in patients in situations where successful tendon healing is unlikely. These include older patients (>65–70 years), patients with chronic full-thickness tears (retracted tears of any size with advanced muscle degeneration) and tears associated with fixed proximal humeral migration (signs of chronic mechanical contact of the greater tuberosity and acromion).

Conclusions

Our understanding of the natural history of rotator cuff disease continues to expand. Following asymptomatic rotator cuff tears found in patients with symptomatic contralateral shoulders is a good model for studying the natural history. Using this model, important information regarding tear initiation, location, size, progression, and survivorship has been gathered. Degenerative tears initiate approximately 15 mm posterior the biceps tendon with less than on third of tears involving the anterior edge of the supraspinatus tendon. Loss of integrity of the anterior supraspinatus tissue is associated with supraspinatus muscle degeneration. A critical tear size of approximately 175 mm2 is associated with early disruption of normal kinematics of the shoulder. Approximately 50% of degenerative tears will progress in size by five years, and full-thickness tears are more likely to enlarge and develop muscle degeneration than partial-thickness tears. As we continue to learn more about the natural history of cuff disease through this model, clinicians will be able to further refine indications for rotator cuff repair.

Acknowledgments

Some studies cited in this paper were publications by the author (Keener] funded by a grant from the NIH. Grant #R01 AR051026

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jason Hsu, Assistant Professor, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Washington, Seattle, WA.

Jay D Keener, Email: keenerj@wustl.edu, Associate Professor, Washington University, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, CB 8233, 660 S Euclid Ave., St. Louis, MO 63110, 314 747-2639, Fx: 314-747-2499.

References

- 1.Dunn WR, Schackman BR, Walsh C, et al. Variation in orthopaedic surgeons’ perceptions about the indications for rotator cuff surgery. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 2005;87(9):1978–84. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keyes EL. Observations on Rupture of the Supraspinatus Tendon: Based Upon a Study of Seventy-Three Cadavers. Annals of surgery. 1933;97(6):849–56. doi: 10.1097/00000658-193306000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neer CS., 2nd Impingement lesions. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1983;(173):70–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Refior HJ, Krodel A, Melzer C. Examinations of the pathology of the rotator cuff. Archives of orthopaedic and traumatic surgery Archiv fur orthopadische und Unfall-Chirurgie. 1987;106(5):301–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00454338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozaki J, Fujimoto S, Nakagawa Y, Masuhara K, Tamai S. Tears of the rotator cuff of the shoulder associated with pathological changes in the acromion. A study in cadavera. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 1988;70(8):1224–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jerosch J, Muller T, Castro WH. The incidence of rotator cuff rupture. An anatomic study. Acta orthopaedica Belgica. 1991;57(2):124–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Needell SD, Zlatkin MB, Sher JS, Murphy BJ, Uribe JW. MR imaging of the rotator cuff: peritendinous and bone abnormalities in an asymptomatic population. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 1996;166(4):863–7. doi: 10.2214/ajr.166.4.8610564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crass JR, Craig EV, Feinberg SB. Ultrasonography of rotator cuff tears: a review of 500 diagnostic studies. Journal of clinical ultrasound: JCU. 1988;16(5):313–27. doi: 10.1002/jcu.1870160506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teefey SA, Hasan SA, Middleton WD, Patel M, Wright RW, Yamaguchi K. Ultrasonography of the rotator cuff. A comparison of ultrasonographic and arthroscopic findings in one hundred consecutive cases. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 2000;82(4):498–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tempelhof S, Rupp S, Seil R. Age-related prevalence of rotator cuff tears in asymptomatic shoulders. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery / American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons [et al] 1999;8(4):296–9. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(99)90148-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sher JS, Uribe JW, Posada A, Murphy BJ, Zlatkin MB. Abnormal findings on magnetic resonance images of asymptomatic shoulders. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 1995;77(1):10–5. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199501000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamaguchi K, Ditsios K, Middleton WD, Hildebolt CF, Galatz LM, Teefey SA. The demographic and morphological features of rotator cuff disease. A comparison of asymptomatic and symptomatic shoulders. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 2006;88(8):1699–704. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamamoto A, Takagishi K, Osawa T, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of a rotator cuff tear in the general population. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery / American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons [et al] 2010;19(1):116–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moosmayer S, Smith HJ, Tariq R, Larmo A. Prevalence and characteristics of asymptomatic tears of the rotator cuff: an ultrasonographic and clinical study. The Journal of bone and joint surgery British volume. 2009;91(2):196–200. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B2.21069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milgrom C, Schaffler M, Gilbert S, van Holsbeeck M. Rotator-cuff changes in asymptomatic adults. The effect of age, hand dominance and gender. The Journal of bone and joint surgery British volume. 1995;77(2):296–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harvie P, Ostlere SJ, Teh J, et al. Genetic influences in the aetiology of tears of the rotator cuff. Sibling risk of a full-thickness tear. The Journal of bone and joint surgery British volume. 2004;86(5):696–700. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.86b5.14747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tashjian RZ, Farnham JM, Albright FS, Teerlink CC, Cannon-Albright LA. Evidence for an inherited predisposition contributing to the risk for rotator cuff disease. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 2009;91(5):1136–42. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gwilym SE, Watkins B, Cooper CD, et al. Genetic influences in the progression of tears of the rotator cuff. The Journal of bone and joint surgery British volume. 2009;91(7):915–7. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B7.22353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keener JD, Steger-May K, Stobbs G, Yamaguchi K. Asymptomatic rotator cuff tears: patient demographics and baseline shoulder function. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery / American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons [et al] 2010;19(8):1191–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2010.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moosmayer S, Tariq R, Stiris M, Smith HJ. The natural history of asymptomatic rotator cuff tears: a three-year follow-up of fifty cases. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 2013;95(14):1249–55. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.00185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moosmayer S, Tariq R, Stiris MG, Smith HJ. MRI of symptomatic and asymptomatic full-thickness rotator cuff tears. A comparison of findings in 100 subjects. Acta orthopaedica. 2010;81(3):361–6. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2010.483993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bassett RW, Cofield RH. Acute tears of the rotator cuff. The timing of surgical repair. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1983;(175):18–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hantes ME, Karidakis GK, Vlychou M, Varitimidis S, Dailiana Z, Malizos KN. A comparison of early versus delayed repair of traumatic rotator cuff tears. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy: official journal of the ESSKA. 2011;19(10):1766–70. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1396-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lahteenmaki HE, Virolainen P, Hiltunen A, Heikkila J, Nelimarkka OI. Results of early operative treatment of rotator cuff tears with acute symptoms. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery / American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons [et al] 2006;15(2):148–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petersen SA, Murphy TP. The timing of rotator cuff repair for the restoration of function. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery / American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons [et al] 2011;20(1):62–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2010.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mall NA, Kim HM, Keener JD, et al. Symptomatic progression of asymptomatic rotator cuff tears: a prospective study of clinical and sonographic variables. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 2010;92(16):2623–33. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Codman EA, Akerson IB. THE PATHOLOGY ASSOCIATED WITH RUPTURE OF THE SUPRASPINATUS TENDON. Annals of surgery. 1931;93(1):348–59. doi: 10.1097/00000658-193101000-00043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hijioka A, Suzuki K, Nakamura T, Hojo T. Degenerative change and rotator cuff tears. An anatomical study in 160 shoulders of 80 cadavers. Archives of orthopaedic and traumatic surgery Archivfur orthopadische und Unfall-Chirurgie. 1993;112(2):61–4. doi: 10.1007/BF00420255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim HM, Dahiya N, Teefey SA, et al. Location and initiation of degenerative rotator cuff tears: an analysis of three hundred and sixty shoulders. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 2010;92(5):1088–96. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mochizuki T, Sugaya H, Uomizu M, et al. Humeral insertion of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus. New anatomical findings regarding the footprint of the rotator cuff. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 2008;90(5):962–9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Minagawa H, Itoi E, Konno N, et al. Humeral attachment of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons: an anatomic study. Arthroscopy: the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery: official publication of the Arthroscopy. Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. 1998;14(3):302–6. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(98)70147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burkhart SS, Esch JC, Jolson RS. The rotator crescent and rotator cable: an anatomic description of the shoulder’s “suspension bridge”. Arthroscopy: the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery: official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. 1993;9(6):611–6. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(05)80496-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gladstone JN, Bishop JY, Lo IK, Flatow EL. Fatty infiltration and atrophy of the rotator cuff do not improve after rotator cuff repair and correlate with poor functional outcome. The American journal of sports medicine. 2007;35(5):719–28. doi: 10.1177/0363546506297539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liem D, Lichtenberg S, Magosch P, Habermeyer P. Magnetic resonance imaging of arthroscopic supraspinatus tendon repair. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 2007;89(8):1770–6. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim HM, Dahiya N, Teefey SA, Keener JD, Galatz LM, Yamaguchi K. Relationship of tear size and location to fatty degeneration of the rotator cuff. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 2010;92(4):829–39. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keener JD, Wei AS, Kim HM, Steger-May K, Yamaguchi K. Proximal humeral migration in shoulders with symptomatic and asymptomatic rotator cuff tears. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 2009;91(6):1405–13. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parsons IM, Apreleva M, Fu FH, Woo SL. The effect of rotator cuff tears on reaction forces at the glenohumeral joint. Journal of orthopaedic research : official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society. 2002;20(3):439–46. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00137-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hsu JE, Reuther KE, Sarver JJ, et al. Restoration of anterior-posterior rotator cuff force balance improves shoulder function in a rat model of chronic massive tears. Journal of orthopaedic research : official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society. 2011;29(7):1028–33. doi: 10.1002/jor.21361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Payne LZ, Deng XH, Craig EV, Torzilli PA, Warren RF. The combined dynamic and static contributions to subacromial impingement. A biomechanical analysis. The American journal of sports medicine. 1997;25(6):801–8. doi: 10.1177/036354659702500612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keener JD, Galatz LM, Teefey SA, et al. A prospective evaluation of survivorship of asymptomatic degenerative rotator cuff tears. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 2014 doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.00099. Accepted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fucentese SF, von Roll AL, Pfirrmann CW, Gerber C, Jost B. Evolution of nonoperatively treated symptomatic isolated full-thickness supraspinatus tears. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 2012;94(9):801–8. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Safran O, Schroeder J, Bloom R, Weil Y, Milgrom C. Natural history of nonoperatively treated symptomatic rotator cuff tears in patients 60 years old or younger. The American journal of sports medicine. 2011;39(4):710–4. doi: 10.1177/0363546510393944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maman E, Harris C, White L, Tomlinson G, Shashank M, Boynton E. Outcome of nonoperative treatment of symptomatic rotator cuff tears monitored by magnetic resonance imaging. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 2009;91(8):1898–906. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brophy RH, Dunn WR, Kuhn JE. Shoulder activity level is not associated with the severity of symptomatic, atraumatic rotator cuff tears in patients electing nonoperative treatment. The American journal of sports medicine. 2014;42(5):1150–4. doi: 10.1177/0363546514526854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Group MS, Unruh KP, Kuhn JE, et al. The duration of symptoms does not correlate with rotator cuff tear severity or other patient-related features: a cross-sectional study of patients with atraumatic, full-thickness rotator cuff tears. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery / American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons [et al] 2014;23(7):1052–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuhn JE, Dunn WR, Sanders R, et al. Effectiveness of physical therapy in treating atraumatic full-thickness rotator cuff tears: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery / American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons [et al] 2013;22(10):1371–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Unruh KP, Kuhn JE, Sanders R, et al. The duration of symptoms does not correlate with rotator cuff tear severity or other patient-related features: a cross-sectional study of patients with atraumatic, full-thickness rotator cuff tears. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery / American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons [et al] 2014;23(7):1052–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dunn WR, Kuhn JE, Sanders R, et al. Symptoms of pain do not correlate with rotator cuff tear severity: a cross-sectional study of 393 patients with a symptomatic atraumatic full-thickness rotator cuff tear. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 2014;96(10):793–800. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hamid N, Omid R, Yamaguchi K, Steger-May K, Stobbs G, Keener JD. Relationship of radiographic acromial characteristics and rotator cuff disease: a prospective investigation of clinical, radiographic, and sonographic findings. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery / American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons [et al] 2012;21(10):1289–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goutallier D, Postel JM, Bernageau J, Lavau L, Voisin MC. Fatty muscle degeneration in cuff ruptures. Pre- and postoperative evaluation by CT scan. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1994;(304):78–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]