Abstract

Background

Severe alopecia areata (AA) is resistant to conventional treatment. Although systemic oral corticosteroids are an effective treatment for patients with severe AA, those drugs have many adverse effects. Corticosteroid pulse therapy has been introduced to increase therapeutic effects and reduce adverse effects. However, the treatment modality in severe AA is still controversial.

Objective

To evaluate the effectiveness of corticosteroid pulse therapy in patients with severe AA compared with treatment with oral cyclosporine with corticosteroid.

Methods

A total of 82 patients with severe AA were treated with corticosteroid pulse therapy, and 60 patients were treated with oral cyclosporine with corticosteroid. Both groups were retrospectively evaluated for therapeutic efficacy according to AA type and disease duration.

Results

In 82 patients treated with corticosteroid pulse therapy, 53 (64.6%) were good responders (>50% hair regrowth). Patients with the plurifocal (PF) type of AA and those with a short disease duration (≤3 months) showed better responses. In 60 patients treated with oral cyclosporine with corticosteroid, 30 (50.0%) patients showed a good response. The AA type or disease duration, however, did not significantly affect the response to treatment.

Conclusion

Corticosteroid pulse therapy may be a better treatment option than combination therapy in severe AA patients with the PF type.

Keywords: Alopecia areata, Cyclosporine, Pulse therapy

INTRODUCTION

Alopecia areata (AA) is a relatively common nonscarring hair loss disorder. Approximately 0.2% of the population has AA, and approximately 1.7% of the population will experience an episode of AA during their lifetime1,2. Although the exact etiology of AA is still unknown, evidence indicates that it may have an autoimmune basis3. Whereas patients with mild to moderate AA have a high rate of spontaneous recovery, severe AA is a refractory condition4. Severe AA does not usually respond to conventional treatments, including topical, intralesional, and systemic steroids; topical sensitizers; anthralin; minoxidil; and photochemotherapy5,6.

Among these treatments, systemic oral corticosteroids have been reported to be effective in patients with extensive AA4,7. Relapse after dose reduction and other adverse effects during long-term therapy, however, have restricted the use of systemic oral corticosteroids8. Burton and Shuster9 introduced corticosteroid pulse therapy for treating AA to increase therapeutic effects and reduce adverse effects. Since then, physicians have tried a range of doses in corticosteroid pulse therapy. Cyclosporine, which is commonly used as an immunomodulatory agent, has a common adverse effect of dose-dependent hypertrichosis10,11. It also decreases the perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrates12. Several studies have shown that the combination therapy of cyclosporine and corticosteroid may be a useful treatment for severe AA13,14.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of high-dose corticosteroid pulse therapy compared with the combination therapy of oral cyclosporine and low-dose corticosteroid in patients with severe AA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this study, 142 patients who presented at the Department of Dermatology, Chung-Ang University Hospital, between January 2009 and September 2012, with extensive AA lesions were retrospectively evaluated. A total of 82 patients with severe AA were treated with high-dose corticosteroid pulse therapy, and 60 patients were treated with oral cyclosporine with low-dose corticosteroid. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) plurifocal (PF) alopecia (with a bald surface exceeding 30% of the scalp), alopecia totalis (AT; with a complete absence of terminal scalp hair), and alopecia universalis (AU; with a total loss of terminal scalp and body hair); and (ii) present activity of the disease clinically corresponding to ongoing hair loss and/or histologically indicated by a perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate in biopsies of lesional skin15,16.

Before treatment, a complete physical examination and laboratory testing, including complete blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, high-sensitive C-reactive protein, electrolyte, liver function test, renal function test, antithyroglobulin antibody, antinuclear antibody, electrocardiography, and chest radiography, were performed.

Patients in the corticosteroid pulse therapy group were admitted to the hospital and treated with methylprednisolone, by using an intravenous infusion pump, at a dose of 1 g/day, twice a day for 3 consecutive days for adults and 10 mg/(kg·day) weekly for 3 weeks for children. During infusion, electrocardiographic parameters and vital signs were consistently measured. Cimetidine was administered at a daily dose of 1,200 mg to prevent gastric adverse effects. After corticosteroid pulse therapy, oral methylprednisolone was given at a dose of 30 mg/day for 3 days. The dose was then tapered to 2.5 mg/day for 2 weeks to avoid steroid withdrawal symptoms. The combination therapy group was treated with oral cyclosporine (2.5 mg/[kg·day]) and methylprednisolone (2.5~5 mg/day) for 4 months. After treatment, the doses of oral cyclosporine and methylprednisolone were gradually tapered, and the drugs were eventually discontinued. Blood pressure, pulse rate, and blood parameters (e.g., renal function test) were regularly measured.

We examined patient characteristics such as sex, age, type of AA, and duration of disease before treatment; evaluated the therapeutic efficacy at 6 months by using the clinical record and photographs; and investigated the adverse effects after treatment. Hair growth was assessed on a percentage scale, ranging from 0% to 100% of regrowth in AA lesions. To observe the association with AA type or duration for the treatment response, we further divided the patients into five groups according to hair regrowth. Only growth of terminal hair from the lesions was considered as regrowth (grade 1: 0%~24%, grade 2: 25%~49%, grade 3: 50%~74%, grade 4: 75%~99%, and grade 5: 100% improvement). For other correlative analyses, we considered regrowth on >50% of the lesional surface as a "good response." During follow-up, a hair loss of >25% was considered a relapse. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 12.0 for Windows statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Analysis of variance and Mann-Whitney U test were used. A p<0.05 was considered as statistically significant. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Chung-Ang University Hospital, Seoul, Korea (IRB No. C2015015[1473]).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

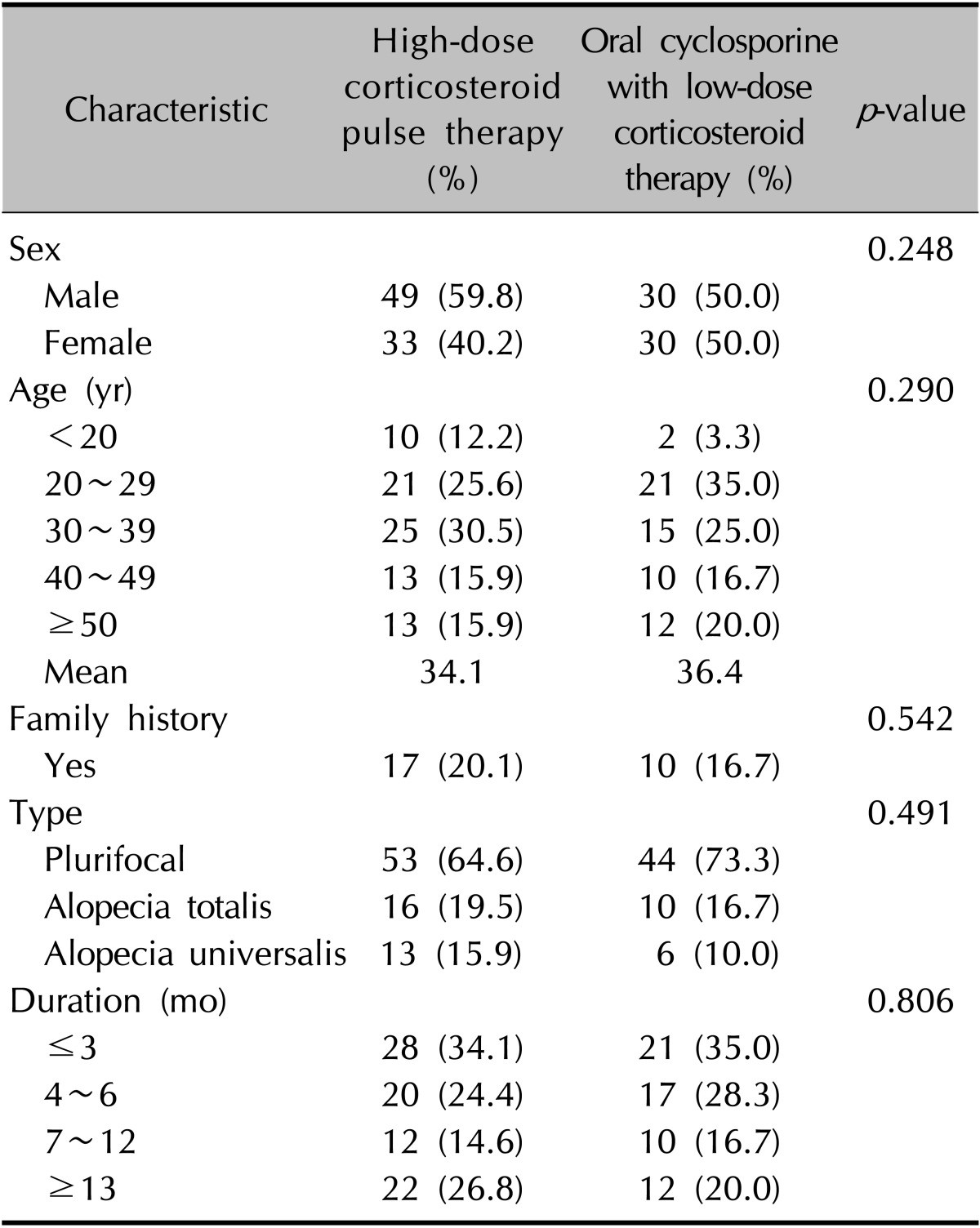

The study consisted of 79 men and 63 women with an age range of 8~80 years (mean, 35.1 years). Twenty-seven (19.0%) of the 142 patients had a family history of AA. The prevalence of the AA type was observed in the following order in both the corticosteroid pulse therapy group and the combination therapy group: PF (68.3%)>AT (18.3%)>AU (13.4%). The mean duration before treatment was 18.6 months (range, 1 month to 24 years; Table 1).

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

Therapeutic effect

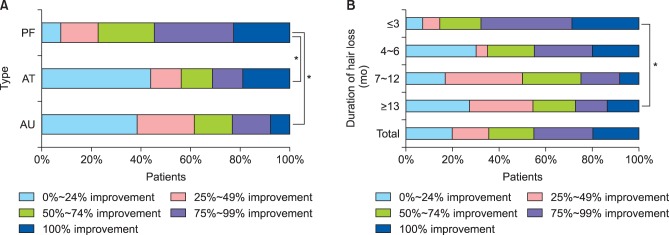

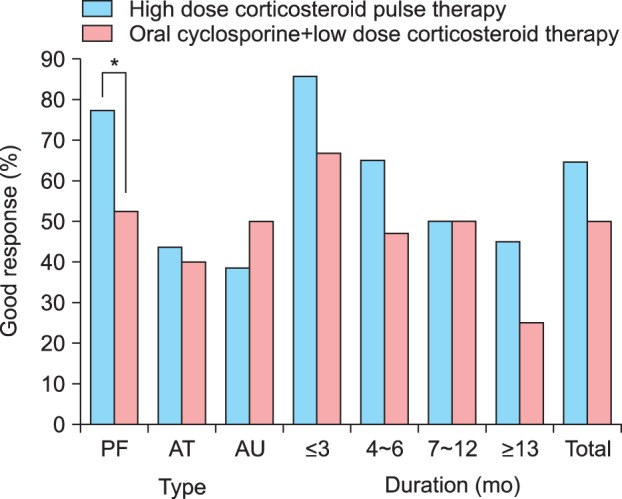

In 82 patients treated with high-dose corticosteroid pulse therapy, 53 (64.6%) were good responders. According to AA types, the PF group showed a better response than the AT or AU group (PF vs. AT, p=0.048; PF vs. AU, p=0.021). In the recent-onset group (duration of AA ≤3 months), 85.7% of the patients were good responders; in the other groups according to onset, 65.0% (4~6 months), 50.0% (7~12 months), and 45.5% (≥13 months) of patients showed a good response. There was a statistically significant difference between the ≤3-month group and the ≥13-month group (p=0.017; Fig. 1). The outcomes did not differ significantly between any of the other groups.

Fig. 1. Comparison of outcomes at 6 months after corticosteroid pulse therapy according to (A) alopecia areata type and (B) duration (*p<0.05, as determined by using ANOVA with post hoc Tukey analysis). PF: plurifocal, AT: alopecia totalis, AU: alopecia universalis.

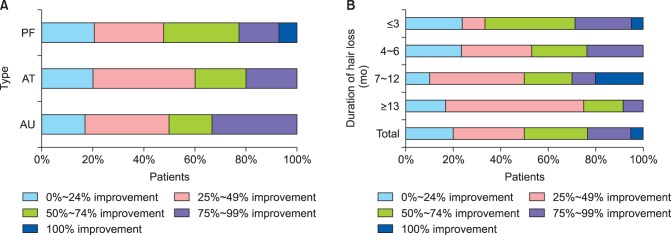

In the 60 patients treated with oral cyclosporine with low-dose corticosteroid, 30 patients (50.0%) showed a good response. Similar to the patients treated with pulse therapy, the PF group showed a better response than the other groups. In addition, the recent-onset group showed a better response than the other groups. The differences, however, were not statistically significant (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Comparison of outcomes at 6 months after oral cyclosporine with low-dose corticosteroid therapy according to (A) alopecia areata type and (B) duration. PF: plurifocal, AT: alopecia totalis, AU: alopecia universalis.

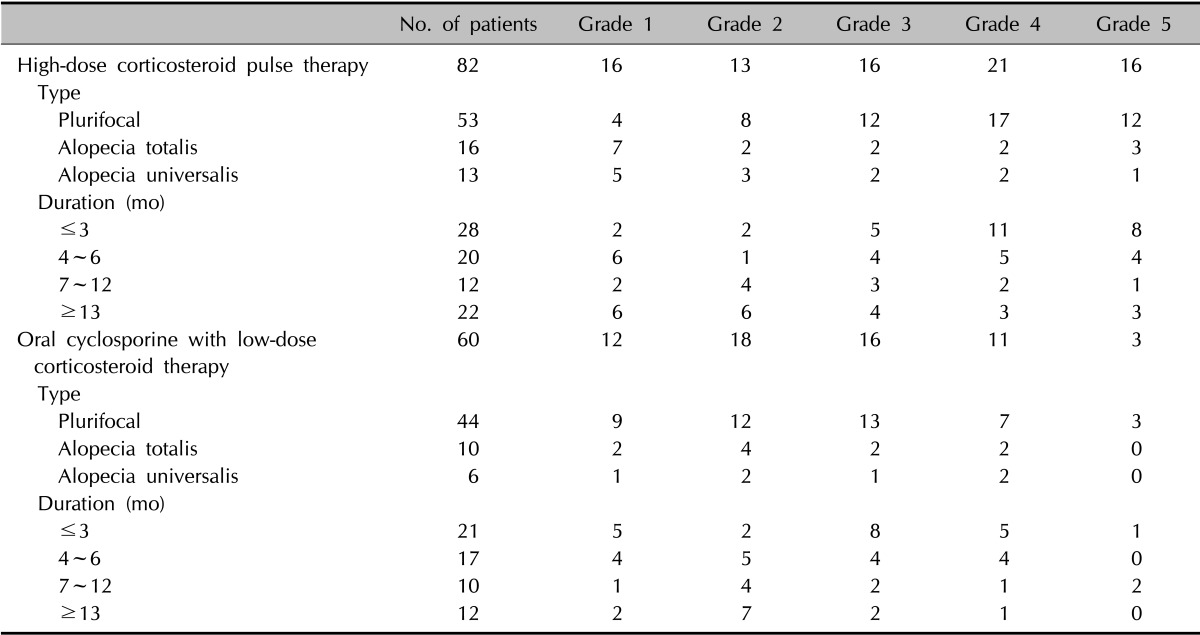

In the comparison of therapeutic efficacy between corticosteroid pulse therapy and combination therapy of oral cyclosporine and corticosteroid, 77.4% of patients with the PF type of AA treated with corticosteroid pulse therapy were good responders, in contrast to 52.3% of the patients with the PF type of AA treated with the combination therapy (p=0.009; Table 2, Fig. 3). The patients treated with corticosteroid pulse therapy had better outcomes than those treated with the combination therapy in the ≤3-month group, the 4- to 6-month group, and the ≥13-month group.

Table 2. Treatment response to high-dose corticosteroid pulse therapy, oral cyclosporine, and low-dose corticosteroid therapy in severe alopecia patients.

Grade 1: 0%~24%, grade 2: 25%~49%, grade 3: 50%~74%, grade 4: 75%~99%, grade 5: 100% improvement (regrowth on >50% of the lesional surface as a good response).

Fig. 3. Comparison of therapeutic efficacy of corticosteroid pulse therapy and combination therapy of oral cyclosporine and corticosteroid (*p<0.05, as determined by using the Mann-Whitney U test). PF: plurifocal, AT: alopecia totalis, AU: alopecia universalis.

Relapse rate

Although the patients were followed from 6 to 48 months after treatment, relapse of AA lesions occurred in 11 of the 55 (20.0%) good responders in the steroid pulse therapy group and 8 of the 30 (26.7%) good responders in the combination therapy group. However, there was no statistically significant difference.

Adverse effects

Adverse effects, including gastrointestinal discomfort, headache, dizziness, facial flushing, and palpitation, were observed in 16 patients (19.5%) in the steroid pulse therapy group. In the combination therapy group, adverse effects, including gastrointestinal discomfort, headache, and hypertension, were observed in 11 patients (18.3%). None of the patients, however, had serious adverse effects requiring cessation of treatment.

DISCUSSION

There is increasing evidence that AA is likely a tissue-specific autoimmune disease. Hair follicle-specific IgG autoantibodies have been found in the peripheral blood of AA patients17. The presence of inflammatory lymphocytes around affected hair follicles on biopsy of AA lesions also supports the autoimmune hypothesis18. Several treatment modalities have been described involving an immunomodulatory mechanism.

In 1975, Burton and Shuster9 first introduced corticosteroid pulse therapy in treating AA to avoid the adverse effects of prolonged corticosteroid therapy. The clinical response was poor because of inappropriate dosage and the selection of patients with chronic severe AA. Since then, many studies have tried to induce AA remission with corticosteroid pulse therapy. The advantages of corticosteroid pulse therapy include fully ligand-occupied glucocorticoid receptors, nongenomic actions, including membrane-bound glucocorticoid receptor-mediated signaling, and direct physicochemical actions on the plasma membrane19. In addition, high corticosteroid levels may help correct the cytokine imbalance systemically or locally.

The standard dose of corticosteroid pulse therapy is unclear. Various treatment protocols have been used, such one course of either 8 mg/(kg·day), 500 mg/day, or 1 g/day methylprednisolone for 3 consecutive days15,16,20. The dosage of methylprednisolone administered in this study was 1 g/day for 3 consecutive days to achieve the maximum plasma concentration. We only performed one course of treatment because it has been shown that multiple courses have no benefit21. In our study, 64.6% of the patients were good responders who showed regrowth on >50% of the lesional surface. This therapeutic effect was similar to that in patients with severe AA in previous studies15,16,22. Some studies have evaluated the prognostic factors for the outcome of corticosteroid pulse therapy. Im et al.20 reported that patients with a disease duration of <6 months and the PF type had better responses to treatment. Seiter et al.16 also suggest that corticosteroid pulse therapy may be a better treatment option for the PF type but not for ophiasic AA, AT, or AU. Similar to these studies, we observed a better response in patients with a disease duration of <3 months and those with the PF type.

Cyclosporine is a common therapeutic agent used in patients who had received organ transplants; this drug selectively and reversibly inhibits the T-cell-mediated immune response. However, a common cutaneous adverse effect of cyclosporine is dose-dependent hypertrichosis due to the prolongation of the anagen phase of the hair cycle10,11. Because corticosteroids are immunosuppressive agents that inhibit the late-phase antigen-dependent inflammatory reaction, combination therapy with cyclosporine as an early immunomodulator at the induction phase may have synergistic effects on immunosuppression23.

Combination therapy with cyclosporine and low-dose corticosteroid to treat AA has been reported as a useful treatment strategy. Previous studies, however, in the treatment of severe AA patients showed variable treatment results for dose regimens like those of corticosteroid pulse therapy. Teshima et al.24 treated six patients with refractory AU with cyclosporine at doses of 2.5 mg/(kg·day) and prednisolone at a dose of 5 mg/day for 7 months. This treatment resulted in clinical improvements for all six patients, and there was no recurrence. Kim et al.13 treated patients with severe AA with cyclosporine (200 mg twice daily) for 7~14 weeks and methylprednisolone (24 mg twice daily for men, 20 mg twice daily for women, and 12 mg twice daily for children) for 3~6 weeks. Thirty-eight of 43 patients experienced considerable hair growth. In this study, 30 of 60 patients (50%) had >50% hair regrowth. There was no relation, however, between therapeutic effect and AA type or disease duration.

Concerning the therapeutic efficacy of corticosteroid pulse therapy compared with that of combination therapy, the treatment responses were not significantly different. The relapse rates of both groups were also not significantly different. Interestingly, however, AA patients with the PF type had significantly better responses to corticosteroid pulse therapy. It was difficult to directly compare this study with previous studies because of the different treatment protocols and patient selection methods. The difference of therapeutic effects compared with previous studies might also be due to the difference of the criteria for good response and the small sample size.

None of the patients in either therapeutic modality had serious adverse effects. Particularly, pulse corticosteroid therapy was tolerable in children. Some previous studies had excluded children because of possible adverse effects such as growth retardation21. Tsai et al.25 however, administered corticosteroids to children <12 years of age, with 5 mg/kg oral prednisolone in three divided doses. Assouly et al.22 administered 500-mg intravenous methylprednisolone daily for 3 consecutive days or 5-mg/kg intravenous methylprednisolone twice daily for 3 consecutive days in children. In the present study, we administered treatment to four children at a dose of 10 mg/kg weekly for 3 weeks, and no adverse effects were noted.

In conclusion, our study compares the therapeutic efficacy of corticosteroid pulse therapy and the combination therapy of oral cyclosporine and corticosteroid for severe AA patients. Corticosteroid pulse therapy seems to be effective in severe AA patients treated within 3 months of disease onset and severe AA patients with the PF type. Especially in severe AA patients with the PF type, corticosteroid pulse therapy may be a better treatment option than combination therapy.

References

- 1.Safavi K. Prevalence of alopecia areata in the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:702. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1992.01680150136027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Price VH. Alopecia areata: clinical aspects. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96:68S. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12471869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shapiro J. Alopecia areata. Update on therapy. Dermatol Clin. 1993;11:35–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacDonald Hull SP, Wood ML, Hutchinson PE, Sladden M, Messenger AG British Association of Dermatologists. Guidelines for the management of alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:692–699. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiedler VC. Alopecia areata. A review of therapy, efficacy, safety, and mechanism. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:1519–1529. doi: 10.1001/archderm.128.11.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lebwohl M. New treatments for alopecia areata. Lancet. 1997;349:222–223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)64857-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madani S, Shapiro J. Alopecia areata update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:549–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winter RJ, Kern F, Blizzard RM. Prednisone therapy for alopecia areata. A follow-up report. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1549–1552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burton JL, Shuster S. Large doses of glucocorticoid in the treatment of alopecia areata. Acta Derm Venereol. 1975;55:493–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kahan BD. Cyclosporine. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1725–1738. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198912213212507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor M, Ashcroft AT, Messenger AG. Cyclosporin A prolongs human hair growth in vitro. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;100:237–239. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12468979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta AK, Ellis CN, Nickoloff BJ, Goldfarb MT, Ho VC, Rocher LL, et al. Oral cyclosporine in the treatment of inflammatory and noninflammatory dermatoses. A clinical and immunopathologic analysis. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:339–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim BJ, Min SU, Park KY, Choi JW, Park SW, Youn SW, et al. Combination therapy of cyclosporine and methylprednisolone on severe alopecia areata. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:216–220. doi: 10.1080/09546630701846095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shapiro J, Lui H, Tron V, Ho V. Systemic cyclosporine and low-dose prednisone in the treatment of chronic severe alopecia areata: a clinical and immunopathologic evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:114–117. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70342-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedli A, Labarthe MP, Engelhardt E, Feldmann R, Salomon D, Saurat JH. Pulse methylprednisolone therapy for severe alopecia areata: an open prospective study of 45 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:597–602. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seiter S, Ugurel S, Tilgen W, Reinhold U. High-dose pulse corticosteroid therapy in the treatment of severe alopecia areata. Dermatology. 2001;202:230–234. doi: 10.1159/000051642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu W, Shapiro J, Yu M, Barekatain A, Lo B, Finner A, et al. Alopecia areata: pathogenesis and potential for therapy. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2006;8:1–19. doi: 10.1017/S146239940601101X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McElwee KJ, Tobin DJ, Bystryn JC, King LE, Jr, Sundberg JP. Alopecia areata: an autoimmune disease. Exp Dermatol. 1999;8:371–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.1999.tb00385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buttgereit F, Wehling M, Burmester GR. A new hypothesis of modular glucocorticoid actions: steroid treatment of rheumatic diseases revisited. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:761–767. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199805)41:5<761::AID-ART2>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Im M, Lee SS, Lee Y, Kim CD, Seo YJ, Lee JH, et al. Prognostic factors in methylprednisolone pulse therapy for alopecia areata. J Dermatol. 2011;38:767–772. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.01135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakajima T, Inui S, Itami S. Pulse corticosteroid therapy for alopecia areata: study of 139 patients. Dermatology. 2007;215:320–324. doi: 10.1159/000107626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Assouly P, Reygagne P, Jouanique C, Matard B, Marechal E, Reynert P, et al. Intravenous pulse methylprednisolone therapy for severe alopecia areata: an open study of 66 patients. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2003;130:326–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferron GM, Pyszczynski NA, Jusko WJ. Gender-related assessment of cyclosporine/prednisolone/sirolimus interactions in three human lymphocyte proliferation assays. Transplantation. 1998;65:1203–1209. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199805150-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teshima H, Urabe A, Irie M, Nakagawa T, Nakayama J, Hori Y. Alopecia universalis treated with oral cyclosporine A and prednisolone: immunologic studies. Int J Dermatol. 1992;31:513–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1992.tb02706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsai YM, Chen W, Hsu ML, Lin TK. High-dose steroid pulse therapy for the treatment of severe alopecia areata. J Formos Med Assoc. 2002;101:223–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]