Abstract

AIM: To determine the frequencies of HGV and TTV infections in blood donors in Hangzhou.

METHODS: RT-nested PCR for HGV RNA detection and semi-nested PCR for TTV DNA detection in the sera from 203 blood donors, and nucleotide sequence analysis were performed.

RESULTS: Thirty-two (15.8%) and 30 (14.8%) of the 203 serum samples were positive for HGV RNA and TTV DNA, respectively. And 5 (2.5%) of the 203 serum samples were detectable for both HGV RNA and TTV DNA. Homology of the nucleotide sequences of HGV RT-nested PCR products and TTV semi-nested PCR products from 3 serum samples compared with the reported HGV and TTV sequences was 89.36%, 87.94%, 88.65% and 63.51%, 65.77% and 67.12%, respectively.

CONCLUSION: The infection rates of HGV and/or TTV in blood donors are relatively high, and to establish HGV and TTV examinations to screen blood donors is needed for transfusion security. The genomic heterogeneity of TTV or HGV is present in the isolates from different areas.

Keywords: China; DNA virus infections/epidemiology; hepatitis, virus, human/epidemiology; blood transfusion/adverse effect; blood donors; hepatitis agents, GB/isolation & purification

INTRODUCTION

Viral hepatitis is relatively common in China[1-12]. Among them hepatitis G virus (HGV) and hepatitis GB virus (GBV-C) were recently identified as the two isolates of a novel positive-stranded RNA virus belonging to Flaviviridae family associated with human non-A-E hepatitis[13,14]. In 1997, a negatively stranded DNA virus, named transfusion transmitted virus (TTV), was isolated from a patient suffering from non-A-G hepatitis. At present TTV was proposed to be a member of a new virus family temporarily named Circinoviridae[15,16]. HGV RNA could be detected in patients with non-A-E hepatitis or fulminant hepatic failure (FHF) at relatively high percentages[17-22] and the coinfection of HGV and HCV may accelerate the progression of chronic liver disease[23-25]. However, many investigation data revealed that HGV was able to establish a long-term asymptomatic viremia in non A-E hepatitis patients and only a few of the patients had biochemical evidence of liver damage[26-30]. TTV DNA was frequently found in non-A-G hepatitis patients with a single elevation of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and the persistence of TTV infection might be a causative factor of human FHF[31-33]. A high frequency of TTV virus infection among patients with non-B, non-C hepatocellular carcinoma was also reported by Nakagawaet al[34]. However, some literatures reported that clinical implication of TTV infection was insignificant because of minimal role of liver injury in non-A-G hepatitis patients[35-37]. The clinical importance of HGV and TTV infections in human hepatic diseases is still present even though the real pathogenic potentials of the two viruses have remained unanswered. Therefore, the prevalence of HGV and TTV infections in blood donors is a significant subject for investigation.

In the present study, HGV RNA and TTV DNA in the serum samples of 203 blood dono rs in Hangzhou, eastern China, were detected using RT-nested PCR and semi-nested PCR, respectively. The HGV RNA or TTV DNA positive amplification products from part of the serum samples were cloned and sequenced. The results of this study may help determine the frequencies of HGV and TTV infections in blood donors in the local area and provide the basis for screening blood donors to control transmission of the two viruses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

A total of 203 serum samples of healthy blood donors were obtained from four hospitals in Hongzhou, Zhejiang Province of China. The blood donors were confirmed to have neither clinical signals of hepatitis and nor elevation of ALT by conventional hepatic examinations, and the serum samples were negative for hepatitis A-C viruses by EIA and PCR. The reagents used in reverse transcription (RT) and PCR were purchased from Sangon and the other reagents used in this study from Sigma.

METHODS

Isolation of serum RNA and DNA Total RNA in 200 μL of each serum samples was prepared by Trizol method according to the manufacturer’s instruction and then dissolved in 50 μL of DEPC treated water. Total DNA in 200 μL of each serum samples was extracted by phenol-chloroform method[38], and then dissolved in 50 μL TE buffer (pH8.0).

RT-nested PCR for HGV RNA detection Ten microliters of total RNA preparation was mixed with 10 μL RT master mixture containing 1 μmol•L¯¹ of random hexanucleotide as primer, 2 mol•L¯¹ each of dNTP, 20 U M-MuLV-reverse transcriptase, 20 U RNase inhibitor and 4 μL of 5 × RT buffer (pH8.3). The steps of RT were described as follows: at 70 °C × 5 min for denaturation, at 42 °C × 60 min for cDNA synthesis, and at 70 °C × 10 min to stop the reaction.

Primers derived from HGV 5’-NCR were used in the RT-nested PCR[39]. External primers: 5’-ATGACAGGGTTGGTAGGTCGTAAATC-3’ (sense), 5’-CCCCACTGGTCCTTGTCAACTCGCCG-3’ (antisense). Internal primers: 5’-TGGTAGCCACTATAGGTGGGTCTTAA-3’ (sense), 5’-ACATTGAAGGGCGACGTGGACCGTAC-3’ (antisense). For the first round PCR, 10 μL of RT product was mixed with 90 μL PCR master mixture containing 250 nmol•L¯¹ each of the primers, 2 mol•L¯¹ each of dNTP, 25 mol•L¯¹ MgCl2, 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase and 10 μL of 10 × PCR buffer (pH9.1). For the second round PCR, 5 μL product from the first round PCR was used as template, and the other reaction reagents were the same as that in the first round PCR except for the primers. The parameters for each of the PCR rounds were: 94 °C 5 min (× 1); 94 °C 1 min, 56 °C 1 min, 72 °C 1.5 min (× 35) and 72 °C 7 min (× 1). The expected size of target fragments amplified from HGV RNA was 193 bp.

Semi-nested PCR for TTV DNA detection The primers used in the semi-nested PCR for TTV DNA detection were the same described by Okamoto et al[40]. External primers: 5’-ACAGACAGAGGAGAAGGCAACATG-3’ (sense), 5’-CTGGCATTTTACCATTTCCAAAGTT-3’ (antisense). Internal primers: 5’-GGCAACATGTTATGATAGACTGG-3’ (sense), 5’-CTGGCATTTTACCATTTCCAAAGTT-3’ (antisense). Except for specific primers, MgCl2 concentration (15 mol•L¯¹), total reaction volume (50 μL) and annealing temperature (60 °C), the compositions and concentrations of other reaction agents and the parameters for semi-nested PCR was the same as that of the RT-nested PCR for HGV detection. The expected size of target fragments amplified from TTV DNA was 271 bp.

Examination of amplification products The results of amplification reactions were observed on UV light after 20 g•L¯¹ ethidium bromide stained agarose electrophoresis, and 100 bp DNA ladder was used as a size marker to estimate the length of products.

Analysis of nucleotide sequences of amplification products The target DNA fragments from HGV or TTV amplification products by PCR were cloned into plasmid pUCm-T-vector using T-A cloning kit according to the manufacturer's instruction. The recombinant plasmid was amplified in E. coli strain DH 5α and then recovered by Sambrook’s method[38]. The nucleotide sequence of inserted fragment was analyzed by Sangon. Homology of the nucleotide sequences was compared with those of reported[13,40].

RESULTS

Positive rates of HGV RNA and TTV DNA in the serum samples

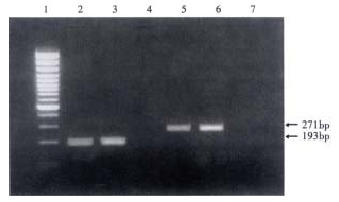

The respective target fagments respectively amplified from HGV RNA and TTV DNA are shown in Figure 1. Thirty-two (15.8%) 30 (14.8%) and 5 (2.5%) of the 203 serum samples were positive for HGV RNA, TTV DNA and both of the two respectively (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Target amplification fragments from HGV RNA and TTV DNA. (1: marker; 2 and 3: HGV positive serum samples; 4: blank for HGV detection; 5 and 6: TTV positive serum samples; 7: blank for TTV detection)

Table 1.

Positive rates of HGV RNA and TTV DNA in the 203 blood donors

| Virus | Tested (n) | Positive (n) | % |

| HGV | 203 | 32 | 15.8 |

| TTV | 203 | 30 | 14.8 |

| HGV and TTV | 203 | 5 | 2.5 |

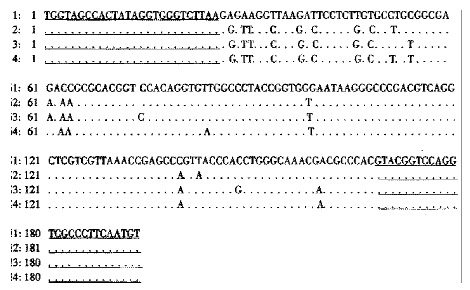

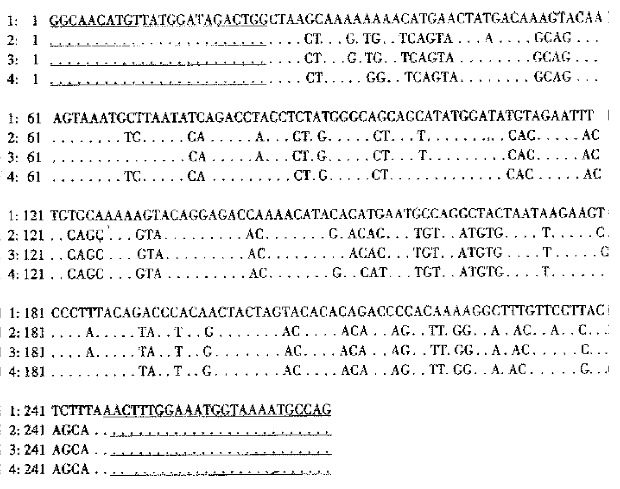

Nucleotide sequence analysis and homology comparison Homology of the nucleotide sequences of HGV RT-nested PCR products from 3 serum samples compared with the reported HGV sequence[13] was 89.36%, 87.94% and 88.65% respectively (Figure 2). Homology of the nucleotide sequences of TTV semi-nested PCR products from 3 serum samples compared with the reported TTV TA278 genotype-1a sequence[40] was 63.51%, 65.77% and 67.12% (Figure 3). The homology in comparison of these sequences mentioned above did not contain the primer sequences.

Figure 2.

Homology of the nucleotide sequences from HGV RT-nested PCR products from 3 serum samples as compared with the reported sequence. (1. The reported HGV sequence[13] ; 2-4. The sequences of HG V RT-nested PCR products from 3 serum samples. Underlined areas indicate the primer positions.)

Figure 3.

Homology of the nucleotide sequences from TTV semi-nested PCR products from 3 serum samples as compared with the reported sequence. 1. The reported TTV sequence[40]; 2-4. The sequences of TTV semi-nested PCR products from 3 serum samples. Underlined areas indicate the primer positions.

DISCUSSION

Viral hepatitis is a common infectious disease in the world and causes a serious healthy problem. Although hepatitis viruses A-E have been demonstrated to be responsible for human hepatitis A-E, approximately 20% of acute and 15% of chronic hepatitis were associated with unknown aetiology[41]. HGV and TTV were recently identified as the transfusion-transmitted viruses and the causative agents of human non-A-E hepatitis[13-15]. However, many investigation data revealed that the patients infected with HGV or TTV were usually asymptomatic and only a few of them showed mild liver injury[42-44]. Therefore, a wide variety of questions about the potential pathogenicity of HGV and TTV infection remain unanswered[31,45-47].

Since HGV and TTV are generally transmitted by transfusion, high infection frequencies of the two viruses in blood recipients and in hemodialyzed patients have been demonstrated[31,43,48-50]. Many investigations demonstrated that HGV RNA was detectable in 1.3%-10.6% of blood donors in different areas abroad[51-55]. Blood donors were also frequently infected with TTV but the infection rates abroad were usually lower than 5%[56,57]. In China, HGV and TTV infection rates in blood donors were reported to be approximately 8% and 15%, respectively[46,58]. In the present study, HGV infection rate in the 203 blood donors was as high as 15.8%, which seems obviously higher than the reported HGV infection rates in the blood donors from other areas of China and abroad. Such high HGV infection rate in the blood donors in Hangzhou is probably due to the geographic difference. In this study, TTV viremia was found in 14.8% of the same 203 blood donors, which is higher than that of the reported abroad but similar to the reported in Chinese blood donors from other areas. In addition, 5 (2.5%) serum samples from the 203 blood donors were positive for both HGV RNA and TTV DNA, indicating the existence of coinfection of the two viruses. However, we can not exactly evaluate the significance of the co-infection because of being unable to get the detailed information of the five co-infection blood donors.

None of the blood donors tested in this study showed clinical symptoms and laboratory markers for hepatitis, which suggested that most of blood donors infected with HGV and/or TTV are usually latent. These asymptomatic blood donors carrying HGV and/or TTV may be more risky and important for the source of infection. Since HGV and TTV at least cause mild hepatitis in human[15,41] and high frequency of HGV and/or TTV infections in blood donors, it is necessary to establish HGV and TTV examination items to screen blood donors for transfusion security.

The nucleotide sequences of HGV RT-nested PCR products from 3 serum samples are highly homologous (87.94%-89.36%) to the HGV sequence reported by Linnen et al[13]. This result of sequence analysis indicates that the RT-nested PCR used in this study is reliable for HGV RNA detection. To analyze the details of the nucleotide sequencing data, it seems to show an HGV genotype different from the literature[59-62]. Lower homology (63.51%-67.12%) of the nucleotide sequences of TTV semi-nested PCR products from 3 serum samples compared with the reported TTV sequence[40] reveals the genomic heterogeneity of TTV in the isolates from different areas, and this founding accords with the conclusions of previously published reports[37,40].

Footnotes

Edited by Ma JY

References

- 1.Han FC, Hou Y, Yan XJ, Xiao LY, Guo YH. Dot immunogold filtration assay for rapid detection of anti-HAV IgM in Chinese. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:400–401. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i3.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang SP, Xu DZ, Yan YP, Shi MY, Li RL, Zhang JX, Bai GZ, Ma JX. Hepatitis B virus infection status in the PBMC of newborns of HBsAg positive mothers. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6(Suppl 3):58. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fang JN, Jin CJ, Cui LH, Quan ZY, Choi BY, Ki M, Park HB. A comparative study on serologic profiles of virus hepatitis B. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:107–110. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i1.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang RX, Gao FG, Zeng LY, Wang YW, Wang YL. Detection of HBV DNA and its existence status in liver tissues and peripheral blood lymphocytes from chronic hepatitis B patients. World J Gastroenterol. 1999;5:359–361. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v5.i4.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheng GG, Zhang JJ, Liu J, Lu DB, Yian XS, Su LW, Yang L, Ming AP. Experiment al and clinical research of predicting chronic hepatitis progressing into serio us hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 1998;4(Suppl 2):92. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiao LY, Yan XJ, Mi MR, Han FC, Hou Y. Preliminary study of a dot immunogold filtration assay for rapid detection of anti-HCV IgG. World J Gastroenterol. 1999;5:349–350. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v5.i4.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song CH, Wu MY, Wang XL, Dong Q, Tang RH, Fan XL. Correlation between HDV infection and HBV serum markers. China Natl J New Gastroenterol. 1996;2:230–231. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu Y, Wang YL, Shi L. Clinical analysis of the efficacy of interferon alpha treatment of hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 1998;4(Suppl 2):85–86. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu YJ, Cong WM, Xie TP, Wang H, Shen F, Guo YJ, Chen H, Wu MC. Detecting the localization of hepatitis B and C virus in hepatocellular carcinoma by double in situ hybridization. China Natl J New Gastroenterol. 1996;2:187–189. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen MY, Huang ZQ, Chen LZ, Gao YB, Peng RY, Wang DW. Detection of hepatitis C virus NS5 protein and genome in Chinese carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile duct and its significance. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:800–804. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i6.800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qiu AG, Qiu RB, Miao Y, Fu ZL, Zhang YR, Zheng YQ, Hong YS, Wu BS, Jia ng YP, Qian CF. Clinical study on therapeutic effect of three-cycle natural the rapy on chronic hepatitis B and C. World J Gastroenterol. 1998;4(Suppl 2):82. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang NS, Liao LT, Zhu YJ, Pan W, Fang F. Follow-up study of hepatitis C virus infection in uremic patients on maintenance hemodialysis for 30 mo. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:888–892. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i6.888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linnen J, Wages J, Zhang-Keck ZY, Fry KE, Krawczynski KZ, Alter H, Koonin E, Gallagher M, Alter M, Hadziyannis S, et al. Molecular cloning and disease association of hepatitis G virus: a transfusion-transmissible agent. Science. 1996;271:505–508. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5248.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leary TP, Muerhoff AS, Simons JN, Pilot-Matias TJ, Erker JC, Chalmers ML, Schlauder GG, Dawson GJ, Desai SM, Mushahwar IK. Sequence and genomic organization of GBV-C: a novel member of the flaviviridae associated with human non-A-E hepatitis. J Med Virol. 1996;48:60–67. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199601)48:1<60::AID-JMV10>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishizawa T, Okamoto H, Konishi K, Yoshizawa H, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. A novel DNA virus (TTV) associated with elevated transaminase levels in posttransfusion hepatitis of unknown etiology. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;241:92–97. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mushahwar IK, Erker JC, Muerhoff AS, Leary TP, Simons JN, Birkenmeyer LG, Chalmers ML, Pilot-Matias TJ, Dexai SM. Molecular and biophysical characterization of TT virus: evidence for a new virus family infecting humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3177–3182. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fiordalisi G, Zanella I, Mantero G, Bettinardi A, Stellini R, Paraninfo G, Cadeo G, Primi D. High prevalence of GB virus C infection in a group of Italian patients with hepatitis of unknown etiology. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:181–183. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang JH, Wei L, Du SC, Wang H, Sun Y, Tao QM. Hepatitis G virus infec tion in patients with chronic non-A-E hepatitis. China Natl J New Gastroenterol. 1997;3:143–146. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v3.i3.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka T, Hess G, Tanaka S, Kohara M. The significance of hepatitis G virus infection in patients with non-A to C hepatic diseases. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:1870–1873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshiba M, Okamoto H, Mishiro S. Detection of the GBV-C hepatitis virus genome in serum from patients with fulminant hepatitis of unknown aetiology. Lancet. 1995;346:1131–1132. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91802-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heringlake S, Osterkamp S, Trautwein C, Tillmann HL, Böker K, Muerhoff S, Mushahwar IK, Hunsmann G, Manns MP. Association between fulminant hepatic failure and a strain of GBV virus C. Lancet. 1996;348:1626–1629. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)04413-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sugai Y, Nakayama H, Fukuda M, Sawada N, Tanaka T, Tsuda F, Okamoto H, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. Infection with GB virus C in patients with chronic liver disease. J Med Virol. 1997;51:175–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagayama R, Miyake K, Okamoto H. Effect of interferon on GB virus C and hepatitis C virus in hepatitis patients with the co-infection. J Med Virol. 1997;52:156–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Francesconi R, Giostra F, Ballardini G, Manzin A, Solforosi L, Lari F, Descovich C, Ghetti S, Grassi A, Bianchi G, et al. Clinical implications of GBV-C/HGV infection in patients with "HCV-related" chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1997;26:1165–1172. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80448-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhong RX, Luo HT, Zhang RX, Li GR, Lu L. Investigation on infection of hepatitis G virus in 105 cases of drug abusers. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6(Suppl 3):63. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarrazin C, Herrmann G, Roth WK, Lee JH, Marx S, Zeuzem S. Prevalence and clinical and histological manifestation of hepatitis G/GBV-C infections in patients with elevated aminotransferases of unknown etiology. J Hepatol. 1997;27:276–283. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alter HJ. The cloning and clinical implications of HGV and HGBV-C. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1536–1537. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199606063342310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feucht HH, Zöllner B, Polywka S, Knödler B, Schröter M, Nolte H, Laufs R. Prevalence of hepatitis G viremia among healthy subjects, individuals with liver disease, and persons at risk for parenteral transmission. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:767–768. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.3.767-768.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alter MJ, Gallagher M, Morris TT, Moyer LA, Meeks EL, Krawczynski K, Kim JP, Margolis HS. Acute non-A-E hepatitis in the United States and the role of hepatitis G virus infection. Sentinel Counties Viral Hepatitis Study Team. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:741–746. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199703133361101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cornu C, Jadoul M, Loute G, Goubau P. Hepatitis G virus infection in haemodialysed patients: epidemiology and clinical relevance. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:1326–1329. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.7.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okamoto H, Akahane Y, Ukita M, Fukuda M, Tsuda F, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. Fecal excretion of a nonenveloped DNA virus (TTV) associated with posttransfusion non-A-G hepatitis. J Med Virol. 1998;56:128–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takayama S, Miura T, Matsuo S, Taki M, Sugii S. Prevalence and persistence of a novel DNA TT virus (TTV) infection in Japanese haemophiliacs. Br J Haematol. 1999;104:626–629. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sugiyama T, Shimizu M, Yamauchi O, Kojima M. [Seroepidemiological survey of TT virus (TTV) infection in an endemic area for hepatitis C virus] Nihon Rinsho. 1999;57:1402–1405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakagawa N, Ikoma J, Ishihara T, Yasui N, Fujita N, Iwasa M, Kaito M, Watanabe S, Adachi Y. High prevalence of transfusion-transmitted virus among patients with non-B, non-C hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;86:1437–1440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kao JH, Chen W, Hsiang SC, Chen PJ, Lai MY, Chen DS. Prevalence and implication of TT virus infection: minimal role in patients with non-A-E hepatitis in Taiwan. J Med Virol. 1999;59:307–312. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199911)59:3<307::aid-jmv8>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gad A, Tanaka E, Orii K, Kafumi T, Serwah AE, El-Sherif A, Nooman Z, Kiyosawa K. Clinical significance of TT virus infection in patients with chronic liver disease and volunteer blood donors in Egypt. J Med Virol. 2000;60:177–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forns X, Hegerich P, Darnell A, Emerson SU, Purcell RH, Bukh J. High prevalence of TT virus (TTV) infection in patients on maintenance hemodialysis: frequent mixed infections with different genotypes and lack of evidence of associated liver disease. J Med Virol. 1999;59:313–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd editor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Lab press; 1989. pp. 24–26, 345-355, 463-468. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yan J, Dennin RH. A high frequency of GBV-C/HGV coinfection in hepatitis C patients in Germany. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:833–841. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i6.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okamoto H, Takahashi M, Nishizawa T, Ukita M, Fukuda M, Tsuda F, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. Marked genomic heterogeneity and frequent mixed infection of TT virus demonstrated by PCR with primers from coding and noncoding regions. Virology. 1999;259:428–436. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heringlake S, Tillmann HL, Manns MP. New hepatitis viruses. J Hepatol. 1996;25:239–247. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(96)80081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tian DY, Yang DF, Xia NS, Zhang ZG, Lei HB, Huang YC. The serological prevalence and risk factor analysis of hepatitis G virus infection in Hubei Province of China. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:585–587. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i4.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang SS, Wu CH, Chen TH, Huang YY, Huang CS. TT viral infection through blood transfusion: retrospective investigation on patients in a prospective study of post-transfusion hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:70–73. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang JH, Wei L, Du SC, Wang H, Sun Y, Tao QM. Hepatitis G virus infec tion in patients with chronic non-A-E hepatitis. China Natl J New Gastroenterol. 1997;3:143–146. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v3.i3.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zanetti AR, Tanzi E, Romanò L, Galli C. GBV-C/HGV: a new human hepatitis-related virus. Res Virol. 1997;148:119–122. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2516(97)89895-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ling BH, Zhuang H, Cui YH, An WF, Li ZJ, Wang SP, Zhu WF. A cross-sectional study on HGV infection in a rural population. World J Gastroenterol. 1998;4:489–492. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v4.i6.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen YP, Liang WF, Zhang L, He HT, Luo KX. Transfusion transmitted virus infection in general populations and patients with various liver diseases in south China. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:738–741. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i5.738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feucht HH, Zollner B, Polywka S, Laufs R. Vertical transmission of hepatitis G. Lancet. 1996;347:615–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moaven LD, Tennakoon PS, Bowden DS, Locarnini SA. Mother-to-baby transmission of hepatitis G virus. Med J Aust. 1996;165:84–85. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1996.tb124854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.de Lamballerie X, Charrel RN, Dussol B. Hepatitis GB virus C in patients on hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1549. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199606063342319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Casteling A, Song E, Sim J, Blaauw D, Heyns A, Schweizer R, Margolius L, Kuun E, Field S, Schoub B, et al. GB virus C prevalence in blood donors and high risk groups for parenterally transmitted agents from Gauteng, South Africa. J Med Virol. 1998;55:103–108. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199806)55:2<103::aid-jmv4>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moaven LD, Hyland CA, Young IF, Bowden DS, McCaw R, Mison L, Locarnini SA. Prevalence of hepatitis G virus in Queensland blood donors. Med J Aust. 1996;165:369–371. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1996.tb125019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goubau P, Andrade FB, Liu HF, Basilio FP, Croonen L, Barreto-Gomes VA. Prevalence of GB virus C/hepatitis G virus among blood donors in north-eastern Brazil. Trop Med Int Health. 1999;4:365–367. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1999.00407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Park YM, Mizokami M, Nakano T, Choi JY, Cao K, Byun BH, Cho CH, Jung YT, Paik SY, Yoon SK, et al. GB virus C/hepatitis G virus infection among Korean patients with liver diseases and general population. Virus Res. 1997;48:185–192. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(97)01450-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blair CS, Davidson F, Lycett C, McDonald DM, Haydon GH, Yap PL, Hayes PC, Simmonds P, Gillon J. Prevalence, incidence, and clinical characteristics of hepatitis G virus/GB virus C infection in Scottish blood donors. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1779–1782. doi: 10.1086/314508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Simmonds P, Davidson F, Lycett C, Prescott LE, MacDonald DM, Ellender J, Yap PL, Ludlam CA, Haydon GH, Gillon J, et al. Detection of a novel DNA virus (TTV) in blood donors and blood products. Lancet. 1998;352:191–195. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)03056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cleavinger PJ, Persing DH, Li H, Moore SB, Charlton MR, Sievers C, Therneau TM, Zein NN. Prevalence of TT virus infection in blood donors with elevated ALT in the absence of known hepatitis markers. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:772–776. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang CH, Zhou YS, Chen RG, Xie CY, Wang HT. The prevalence of transfusion transmitted virus infection in blood donors. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:268–270. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i2.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.López-Alcorocho JM, Castillo I, Tomás JF, Carreño V. Identification of a novel GB type C virus/hepatitis G virus subtype in patients with hematologic malignancies. J Med Virol. 1999;57:80–84. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199901)57:1<80::aid-jmv12>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith DB, Cuceanu N, Davidson F, Jarvis LM, Mokili JL, Hamid S, Ludlam CA, Simmonds P. Discrimination of hepatitis G virus/GBV-C geographical variants by analysis of the 5' non-coding region. J Gen Virol. 1997;78(Pt 7):1533–1542. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-7-1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Muerhoff AS, Simons JN, Leary TP, Erker JC, Chalmers ML, Pilot-Matias TJ, Dawson GJ, Desai SM, Mushahwar IK. Sequence heterogeneity within the 5'-terminal region of the hepatitis GB virus C genome and evidence for genotypes. J Hepatol. 1996;25:379–384. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(96)80125-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang XT, Zhuang H, Song HB, Li HM, Zhang HY, Yu Y. Partial sequencing of 5' noncoding region of 7 HGV strains isolated from different areas of China. World J Gastroenterol. 1999;5:432–434. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v5.i5.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]