Abstract

We demonstrate 2 novel mutations of the LHCGR, each homozygous, in a 46,XY patient with severe Leydig cell hypoplasia. One is a mutation in the signal peptide (p.Gln18_Leu19ins9; referred to here as SP) that results in an alteration of the coding sequence of the N terminus of the mature mutant receptor. The other mutation (p.G71R) is also within the ectodomain. Similar to many other inactivating mutations, the cell surface expression of recombinant human LHR(SP,G71R) is greatly reduced due to intracellular retention. However, we made the unusual discovery that the intrinsic efficacy for agonist-stimulated cAMP in the reduced numbers of receptors on the cell surface was greatly increased relative to the same low number of cell surface wild-type receptor. Remarkably, this appears to be a general attribute of misfolding mutations in the ectodomains, but not serpentine domains, of the gonadotropin receptors. These findings suggest that there must be a common, shared mechanism by which disparate mutations in the ectodomain that cause misfolding and therefore reduced cell surface expression concomitantly confer increased agonist efficacy to those receptor mutants on the cell surface. Our data further suggest that, due to their increased agonist efficacy, extremely small changes in cell surface expression of misfolded ectodomain mutants cause larger than expected alterations in the cellular response to agonist. Therefore, for inactivating LHCGR mutations causing ectodomain misfolding, the numbers of cell surface mutant receptors on fetal Leydig cells of 46,XY individuals exert a more exquisite effect on the relative severity of the clinical phenotypes than already appreciated.

The lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor (LHR) is a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) that plays a central role in reproductive endocrinology. The LHR is composed of a large extracellular domain, which mediates high-affinity hormone binding, attached to a 7 transmembrane serpentine domain related to the family A of GPCRs (1, 2). Due to the nearly identical structures of LH and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), each of these hormones can bind to the hLHR and initiate similar signaling cascades, the primary one being the activation of Gs, which results in an increased production of intracellular cAMP (1). From the time of puberty onward, pituitary LH mediates processes in the ovaries and testes of females and males, respectively, that are necessary for fertility. In addition, though, the testicular hLHR plays an important role during fetal development. During the first trimester of gestation, placental hCG binds to hLHR on fetal Leydig cells, thus stimulating the secretion of fetal testosterone, which mediates the development of male external and internal genitalia in 46,XY fetuses. In the absence of androgen action during human fetal development, the external genitalia remain female, irrespective of chromosomal or gonadal sex. Consequently, homozygous or compound heterozygous loss-of-function mutations, also referred to as inactivating mutations, of the LHCGR (ie, gene encoding the hLHR) are associated with rare autosomal recessive forms of 46,XY disorders of sex development (3, 4). Although severe loss-of-function mutations of the LHCGR cause Leydig cell hypoplasia and result in ambiguous or female external genitalia in 46,XY individuals, milder mutations result in hypospadias and/or micropenis and hypogonadism. In 46,XX individuals, loss-of-function mutations of the LHCGR cause oligo-amenorrhea and infertility (5).

Structurally, the LHR is most closely related to other members of the glycoprotein hormone receptor family, the FSH receptor (FSHR), which is the other gonadotropin receptor, and the TSH receptor. The glycoprotein hormone receptors are each composed of a large ectodomain attached to a GPCR family A serpentine domain composed of the prototypical 7 transmembrane helices. By mechanisms that are not yet fully elucidated, the binding of hormone to the ectodomain stabilizes the serpentine domain in an active conformation that primarily, although not exclusively, activates Gs. Recent crystal structures of the hFSHR ectodomain complexed with FSH have provided particularly valuable insights into potential mechanisms governing receptor activation (6, 7). The hLHR and hFSHR have each been shown to form homomers and heteromers, with both the ectodomains and serpentine domains contributing to receptor associations (8–11). Receptor associations were shown to initiate in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and be independent of receptor activation, suggesting an obligate and constitutive process (8, 9).

Loss-of-function mutations of the LHCGR are defined as mutations that give rise to cells exhibiting decreased or absent hormone responsiveness. Although mutations may directly affect hormone binding affinity or coupling of the receptor to Gs, the most frequent basis for a loss-of-function mutation of the LHCGR is a mutation that causes misfolding of the hLHR protein. Such mutations, which may occur anywhere in the receptor, cause the receptor to be retained in the ER by the cell's quality control system, thereby resulting in decreased or absent cell surface expression of the receptor (3, 12, 13).

In this study, we identified 2 independent homozygous mutations of the LHCGR present in a 46,XY patient with Leydig cell hypoplasia. Each of the mutations results in an alteration of the coding sequence within the ectodomain of the receptor. To determine the functional properties of the mutant receptors, recombinant hLHRs recapitulating the mutations were characterized. Not surprisingly, the introduction of the mutations singly or in combination into recombinant hLHR resulted in mutant receptors with decreased cell surface expression. However, quite remarkably, these mutants exhibited increased efficacy with respect to hCG-stimulated cAMP production, which, to our knowledge, has not previously been observed in either naturally occurring or engineered hLHR mutants. We further show that other naturally occurring misfolding mutations within the hLHR or hFSHR ectodomains, but not serpentine domains, similarly exhibit increased efficacy of hormone-stimulated cAMP production.

Materials and Methods

Patient

A 13-year and 4-month-old girl presented on account of delayed puberty. Preliminary investigations performed before her presentation at her local hospital showed elevated gonadotropin concentrations (FSH, 11.44 mIU/mL; LH, 16.81 mIU/mL) and low estradiol (17β-estradiol < 0.5 pg/mL) and testosterone (0.02 ng/mL) concentrations. A pelvic ultrasound scan failed to reveal uterine or ovarian structures but showed the presence of possible testicular structures in the inguinal regions bilaterally.

The patient was born at term by normal vaginal delivery. Her birth weight was 3.3 kg, and her birth length was 49 cm. There were no complications during pregnancy or in the neonatal period. The past medical history was unremarkable. She was adopted immediately after birth, and there was no information on family history.

On clinical examination, her height was 168 cm, her weight was 77 kg, and her body mass index was 27.3 kg/m2. She had Tanner stage I breast development and Tanner stage II of pubic hair and axillary hair development. Her external genitalia were unequivocally female with no clitoromegaly. Clinical examination was otherwise unremarkable. Endocrine evaluation at our hospital revealed normal thyroid function and normal 8 am plasma ACTH and serum cortisol concentrations (Supplemental Table 1). The baseline concentrations of LH and FSH were elevated (18.24 mIU/ML and 12.30 mIU/mL, respectively) and increased further (55.52 and 18.94 mIU/mL, respectively) 60 minutes after gonadotropin releasing hormone (100 μg) stimulation. Androgen concentrations were low and did not increase in response to a 3-day hCG (1500 IU daily) stimulation (Supplemental Table 2). Her karyotype was 46,XY and she was SRY(+). Magnetic resonance imaging scan of the pelvis confirmed the presence of oval structures in the inguinal regions bilaterally, which were of maximum diameters of 2 cm on the left side and 2.5 cm on the right side, and were thought to represent degraded testes. She subsequently underwent diagnostic laparoscopy and removal of the gonads. Histologic examination confirmed those to be immature testes. Examination under anesthesia confirmed the presence of hypoplastic vagina of maximum length of 2 cm. She was started on treatment with ethinylestradiol transdermally and is currently awaiting vaginoplasty.

Genetic studies on the patient were undertaken after approval by the Aghia Sophia Children's Hospital on the Ethics of Human Research and written informed consent was obtained from the parents of the patient.

Sequencing of the LHCGR gene

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood lymphocytes employing the Maxwell 16 instrument for automated DNA extraction (Promega). Exons 1–11 of the LHCGR gene were amplified by PCR using different sets of intronic primers. Amplification was performed for 30 cycles in a Gene Amp PCR system (9600; PerkinElmer Cetus). All PCR products were sequenced using the ABI PRISM dye terminator reaction kit (PerkinElmer Cetus) in an ABI PRISM 377 automatic DNA sequencer (PerkinElmer Cetus).

Transfections of cells with recombinant receptors

The cDNA for the wild-type (wt) hLHR was provided to us by Ares Advanced Technology (Ares-Serono Group) and the cDNA was inserted into pcDNA3.1(neo) (Invitrogen). Site-directed mutagenesis using standard methodologies was used to generate the insertion and/or substitution of amino acids predicted by mutations of the patient's LHCGR. When epitope tagged with c-myc, this was placed at the predicted N terminus of the mature hLHR(wt) (ie, just before the amino acid sequence LREAL). For hLHR(SP), hLHR(G71R), and hLHR(SP,G71R), the myc eptitope tag was also inserted just before the amino acid sequence LREAL. The placement of a small epitope tag on the N terminus of hLHR(wt) is known not to affect cell surface expression, binding, or signaling properties. Plasmids were prepared using QIAGEN maxiprep kits (QIAGEN), and sequences were confirmed by automated DNA sequencing (performed by the DNA Core Facility of the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine). Highly purified recombinant hCG and FSH were purchased from Dr A. Parlow of the National Hormone and Pituitary Program and were used for all experiments except for nonspecific binding. Purified hCG and FSH were iodinated as previously described (14). For the determinations of nonspecific binding in 125I-hCG and 125I-FSH binding assays, a crude preparation of hCG and pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (each from Sigma) were used, respectively. Human embryonic kidney (HEK)293 cells were obtained from the American Type Tissue Collection and were maintained, plated for experiments, and transiently transfected as previously described (8). HEK293 cells do not express endogenous LHR or FSHR, and this was confirmed by our laboratory experimentally. When transfecting cells with different concentrations of plasmids encoding receptor cDNA, the total amount of plasmids were kept constant using empty vector. Stably transfected HEK293 cells were generated and maintained as described previously (15).

Determination of intracellular cAMP production

Intracellular cAMP was measured under basal conditions and in response to highly purified recombinant hCG or FSH in transfected HEK293 cells as previously described (16). When stimulating cells with maximally effective hormone concentrations, final concentrations of hCG and FSH were 300 and 500 ng/mL, respectively.

Hormone binding assays

Maximal cell surface hormone binding capacity was determined as previously described using intact cells incubated with a saturating concentration of 125I-hCG (500-ng/mL final concentration) with or without an excess of unlabeled crude hCG (50-IU/mL final concentration) (16) or a 125I-FSH (300-ng/mL final concentration) with or without an excess of pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (220-IU/mL final concentration). Determination of the Ki for competition of 125I-hCG by unlabeled hCG was performed by incubating intact cells with a subsaturating concentration of 125I-hCG (10-ng/mL final concentration) and increasing concentrations of the same preparation of highly purified recombinant, unlabeled, hCG. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software.

Flow cytometry determinations

HEK293 cells were washed once with filtered PBS for immunohistochemistry (PBS-IH) (137mM NaCl, 2.7mM KCl, 1.4mM KH2PO4, and 4.3mM Na2HPO4; pH 7.4). Cells were then detached by washing with PBS-IH and collected by gentle centrifugation. Cells were resuspended in the presence or absence 9E10 monoclonal anti-myc antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc) diluted 1:20 in PBS-IH containing 0.5% BSA (PBS-IH/BSA) and incubated 1 hour at 4°C. The cells were then washed with PBS-IH/BSA and incubated 1 hour at 4°C with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat antimouse IgG (1:350) (Sigma) in PBS-IH/BSA. Cells were washed with PBS-IH/BSA, resuspended in 1-mL PBS-IH/BSA, and filtered through a 70-μm BD Falcon cell strainer into a clean test tube on ice. A BD DiVa fluorescence-activated cell sorter with a 488-nm laser was then used to quantify cell surface expression in 10 000 cells from each experimental group. Control gating was set using cells transfected with empty vector and stained with antibody as described. Arbitrary fluorescence units describing total cell surface fluorescence were determined as the product of the percent cells gated and the geometric mean fluorescence of the sample minus the respective product in the control (empty vector) group.

Homology modeling of the extracellular domain of the hLHR

A homology model was created for the extracellular domain of hLHR using the program Modeler (17). The entire extracellular domain structure of hFSHR served as the template (PDB code 4AY9). A sequence alignment performed by Clustal (18) for the hLHR and hFSHR ectodomains was used as part of the input for homology modeling. The G71R mutation was introduced in hLHR after the alignment was carried out for the wt sequences. Figures were produced in Pymol (http://www.pymol.org).

Results

Histological and genetic studies

Histological analyses performed on the patient's gonads showed immature seminiferous tubules containing Sertoli cells (Supplemental Figure 1A) that stained positive for inhibin B (Supplemental Figure 1B). The absence of elastic fibers in the seminiferous tubules (Supplemental Figure 1C) is consistent with the testes being immature. Of particular significance is the relative absence of Leydig cells in the interstitial tissue. The few rare Leydig cells were confirmed by calretinin staining (Supplemental Figure 1D). Overall, the clinical presentation of the patient is consistent with a 46,XY severe disorder of sexual differentiation due to Leydig cell hypoplasia.

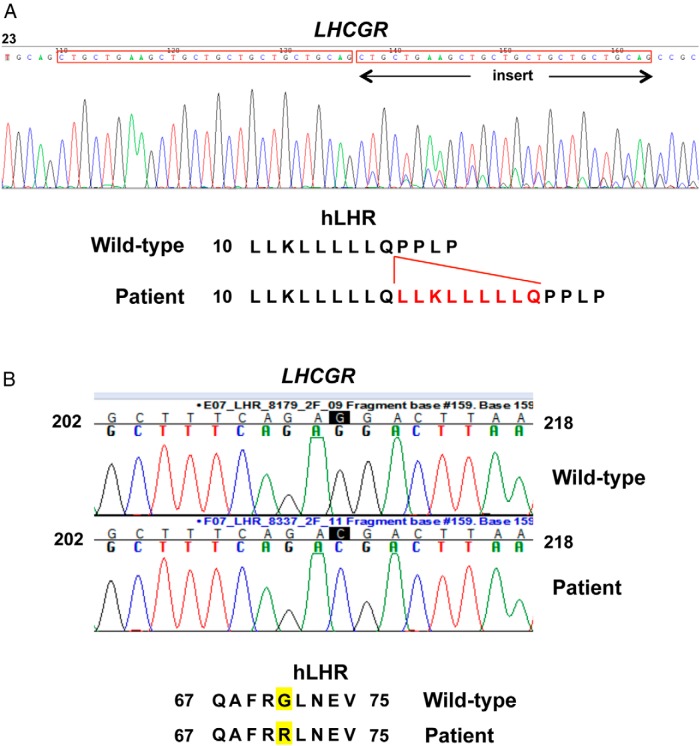

Genetic analyses were performed to determine whether the patient's disorder of sexual differentiation was attributable to 1 or more mutations in the LHCGR gene. Sequencing of the exons of the LHCGR indicated that the patient had 2 distinct novel homozygous mutations within the gene. One was an insertion of 27 consecutive nucleotides after nucleotide 54 within exon 1 of the LHCGR (Figure 1A). The resulting hLHR mutation is an in-frame insertion of 9 residues (a duplication of amino acids 10 through 18) between amino acids 18 and 19, residues that lie within the predicted signal peptide of the hLHR. For simplicity, this signal peptide mutation (p.Gln18_Leu19ins9) is referred to here as SP. The sequencing data of the patient unexpectedly also revealed another homozygous mutation, substitution of C for G at nucleotide 211 within exon 2 of the LHCGR, resulting in a p.G71R mutation in the ectodomain of the receptor protein (Figure 1B). Because the patient was adopted shortly after birth and her family history is not available, genetic studies could not be performed on her biological parents or potential siblings.

Figure 1.

Identification of a 2 different homozygous mutations of the LHCGR in a 46,XY patient with Leydig cell hypoplasia. A, LHCGR sequencing data and the corresponding mutation for hLHR(p.Gln18_Leu19ins9), designated as SP in the article. The noted insertion is due to a duplication of the preceding 27 nucleotides. B, The LHCGR sequencing data and the corresponding mutation of hLHR(G71R).

Functional analyses of hLHR mutants

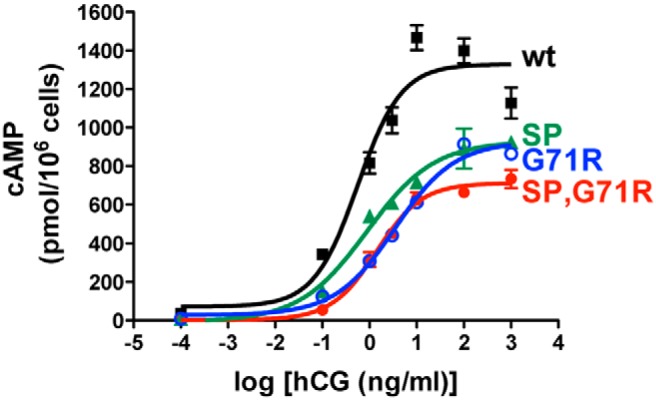

A recombinant hLHR containing both the SP and G71R mutations was generated to recapitulate the presence of both of these mutations in homozygous form in the patient's LHCGR gene. To determine the contributions of each of the mutations individually, hLHR mutants expressing only the SP mutation or only the G71R mutation were also constructed. The overall hormonal responsiveness of cells expressing a given receptor is dictated by the combined contributions of the numbers of cell surface receptors and the intrinsic signaling efficacy of the receptor. For determining the overall cellular responsiveness of cells expressing hLHR(wt) vs hLHR(SP,G71R), HEK293 cells were transfected with maximal and equal concentrations of plasmids encoding each receptor. As shown in Figure 2, cells expressing hLHR(SP,G71R), hLHR(SP), or hLHR(G71R) each exhibited decreased hormone responsiveness relative to cells expressing hLHR(wt). Thus, over 3 experiments the fold differences in EC50s of the mutants relative to hLHR(wt) were 3.43 ± 0.007, 1.83 ± 0.18, and 3.43 ± 1.43, respectively, and fold differences in the maximal responses were 0.698 ± 0.083, 0.825 ± 0.063, and 0.797 ± 0.133.

Figure 2.

Overall responsiveness to hCG of cells expressing the patient's hLHR mutations. HEK293 cells were transfected with the same maximal concentrations of plasmids expressing myc-hLHR(wt), myc-hLHR(G71R), myc-hLHR(SP), or myc-hLHR(SP,G71R), and dose-response curves for hCG-stimulated cAMP were determined. Data points are the mean ± SD of triplicate determinations from 1 experiment representative of 3 independent experiments.

To determine the cell surface expression of each of the mutant hLHRs, flow cytometry was performed on intact HEK293 cells transfected with maximal and equal concentrations of each construct modified to contain a myc epitope tag on the N terminus of the mature protein. Introduction of the individual G71R or SP mutations into the hLHR decreased receptor cell surface expression to 37.5% and 22.2%, respectively, of that observed for hLHR(wt), and the combined hLHR(SP,G71R) mutant exhibited only 4.0% of the cell surface receptor expressed by hLHR(wt) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Decreased Cell Surface Expression of the Patient's hLHR Mutants

| hLHR Construct | % Cell Surface Expression |

|---|---|

| wt | 100 |

| G71R | 37.5 ± 2.8 (n = 6) |

| SP | 22.2 ± 2.8 (n = 7) |

| SP,G71R | 4.00 ± 3.0 (n = 8) |

HEK293 were transiently transfected with the indicated hLHR constructs, each containing a myc epitope tag, and cell surface expression relative to hLHR(wt) was determined by flow cytometry.

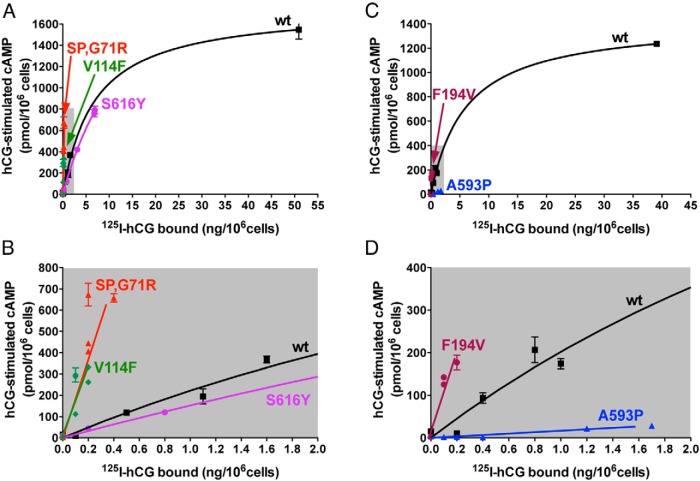

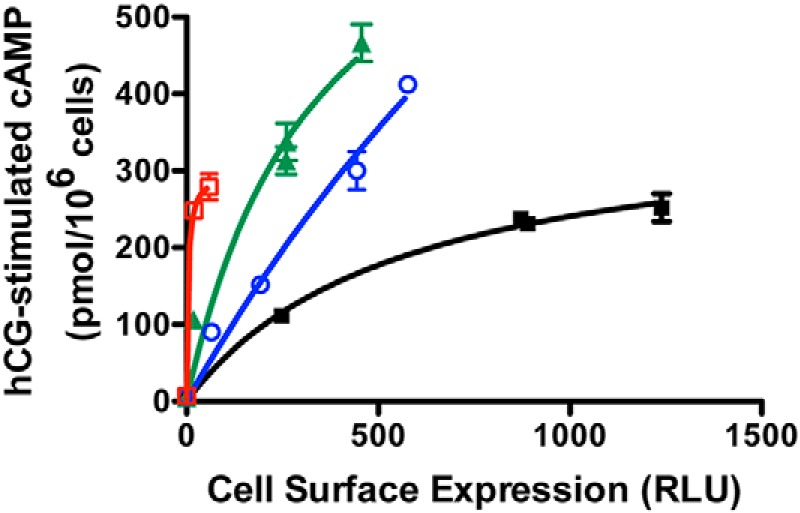

We next sought to measure the intrinsic signaling efficacy of each receptor mutant. Similar to other GPCRs, basal and agonist-stimulated signaling properties of the hLHR are highly dependent on the number of cell surface receptors (16, 19). Therefore, it is necessary to compare the signaling properties of different receptor constructs in cells where each are expressed at the same cell surface density. Agonist-stimulated cAMP production by the hLHR displays a hyperbolic, not linear, relationship with receptor density (19). Consequently, one can't measure hCG-stimulated cAMP and normalize the data relative to receptor expression as is done for some other GPCRs (10, 20). Although one can transfect cells to try to obtain cells with the same numbers of cell surface receptors, as we have done in numerous other studies (eg, Refs. 21–26), this approach is fraught with difficulties in that it is typically extremely difficult to match receptor expression tightly enough to avoid ambiguities in data interpretation. A more robust means to compare signaling activities between receptors is to assay a given receptor over a range of cell surface densities, allowing interpolation of the curves to compare signaling at a given receptor density within the curves (16, 19). Therefore, to assess the intrinsic signaling efficacy of hLHR(wt), hLHR(SP), hLHR(G71R), and hLHR(SP,G71R), experiments were performed examining the cAMP response to a maximally stimulatory concentration of hCG as a function of varying cell surface receptor densities as determined by flow cytometry. In these experiments, cells were transfected with maximal and submaximal concentrations of plasmids encoding each of the mutants, whereas cells were transfected with only submaximal concentrations of hLHR(wt) to deliberately yield cell surface receptor densities in a similar range as the mutants. As shown in Figure 3, the results observed were striking, with the mutants hLHR(SP), hLHR(G71R), and hLHR(SP,G71R) each displaying greater intrinsic efficacies for hCG-stimulated cAMP than hLHR(wt). Thus, examining any given density of cell surface receptors, the maximal hCG-stimulated cAMP response was greatest for hLHR(SP,G71R), followed by hLHR(SP), followed by hLHR(G71R), and then finally hLHR(wt). Therefore, even though the maximal cell surface expression of hLHR(SP,G71R) was barely detectable, the low numbers of cell surface hLHR(SP,G71R) yielded a maximal response to hCG far greater than comparable low numbers of hLHR(wt). Basal concentrations of cAMP did not indicate constitutive activity for any of the mutants (data not shown).

Figure 3.

The patient's hLHR mutants exhibit greater efficacies of hCG-stimulated cAMP relative to hLHR(wt). HEK293 cells were transfected with varying concentrations of plasmids encoding either myc-hLHR(wt), myc-hLHR(G71R), myc-hLHR(SP), or myc-hLHR(SP,G71R). Within the same experiment, relative cell surface receptor expression was determined by flow cytometry on intact cells (and reported as RLU, relative light units), and cAMP responses to a maximally stimulating concentration of hCG were determined. Data points are the mean ± SD of triplicate determinations from 1 experiment representative of 3 independent experiments.

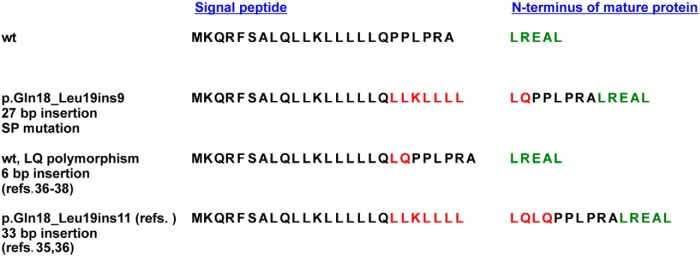

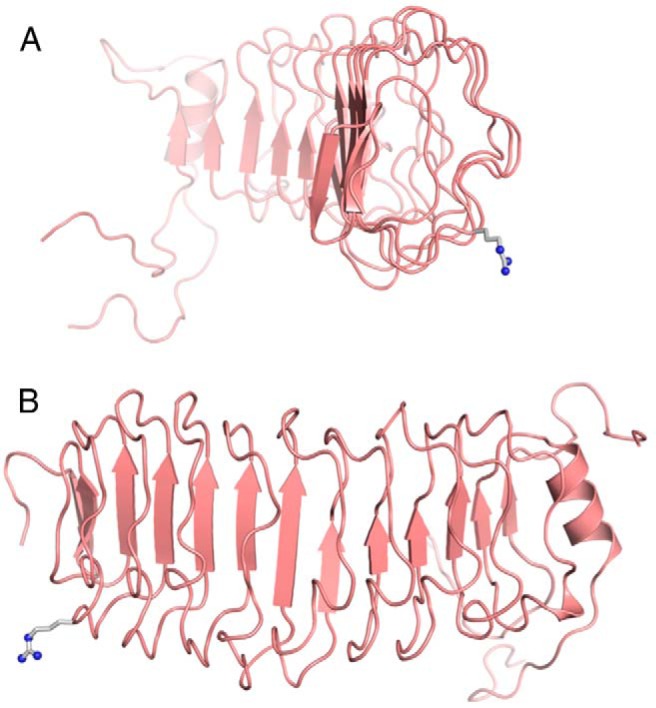

To determine structural changes in the hLHR protein potentially caused by the SP and G71R mutations, the following strategies were employed. Using structural data available for the extracellular domain of the mature hFSHR protein (7, 27), a homology model of the extracellular domain of the hLHR was constructed and used to predict the location and orientation of the arginine introduced in the hLHR(G71R) mutant (Figure 4). Notably, residue 71 of the hLHR is not located in the concave hormone-binding surface of the extracellular domain. It was not possible to similarly model the SP mutation, because it resides within the signal peptide sequence of the hLHR. We questioned whether the SP mutation may alter the cleavage site of the signal peptide, thereby altering the N terminus of the mature protein. Due to the extreme challenges of purifying sufficient quantities of the mature form of a GPCR and determining its N-terminal amino acid sequence, this approach has very rarely been used to determine the cleavage site of the signal peptide in GPCRs (28). Instead, computational methods typically employing the SignalP algorithm are routinely used for this purpose (29–32). We therefore used the most recently updated SignalP 4.1 algorithm to ascertain whether the SP mutation might alter the cleavage of the signal peptide and therefore the sequence of the mature receptor protein (32). The first 29 residues of the coding sequence of hLHR(wt) are shown in Figure 5. The cleavage site for hLHR(wt) is predicted to occur after residue 24, thus causing the N terminus of the mature protein to initiate with the amino acid sequence LREAL. When the 9 amino acid insertion corresponding to the SP mutation in our patient is introduced into the receptor sequence, cleavage of the signal peptide is predicted to occur after residue 25, resulting in a different N-terminal sequence for the mature mutant SP receptor protein that contains an 8 residue extension upstream of the N terminus of the mature wt hLHR. Therefore, although the mutation occurs within the signal peptide, the amino acid sequence of the mature protein, specifically the N-terminal sequence of the ectodomain, is altered. The altered sequence of the mature protein most likely is the basis for the decreased cell surface expression of hLHR(SP) and contributes as well to the decreased cell surface expression of hLHR(SP,G71R).

Figure 4.

Predicted location of Arg71 in the hLHR. Shown in ribbon representations are predicted structures of the extracellular hormone-binding domain of the hLHR as seen from the side (A) or from the back (B). β-Sheet structures are depicting by arrows. Hormone binding occurs within the concave, β-sheet-containing face of the extracellular domain. The side chain of Arg71 (as it would be in the G71R mutant) is shown as a ball-and-stick model in gray.

Figure 5.

Predicted signal peptide cleavage sites of hLHR polymorphic and mutant variants containing inserts after nucleotide 54 (residue 18). The predicted signal peptide for hLHR(wt) is shown in black, and the predicted initial amino acids of the extreme N terminus of the mature hLHR(wt) are shown in green. Residues inserted in polymorphic or mutant hLHRs containing inserts after nucleotide 54 (residue 18) are shown in red. The space between the signal peptide and N terminus of the mature protein for each hLHR variant reflects the signal peptide cleavage site predicted by SignalP 4.1.

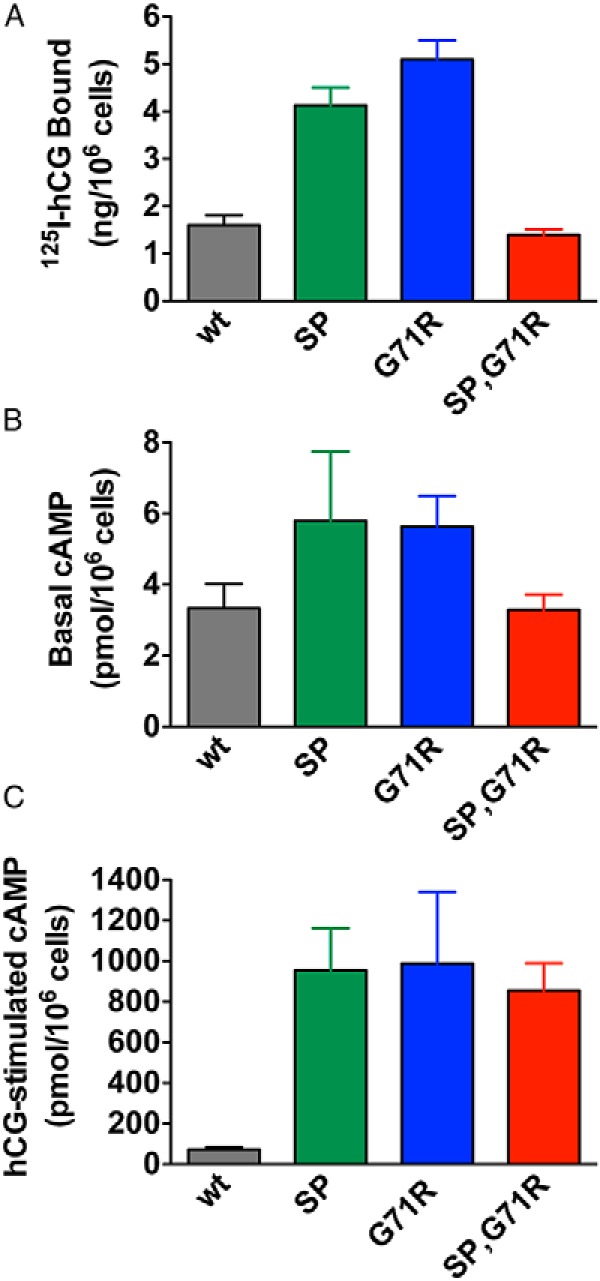

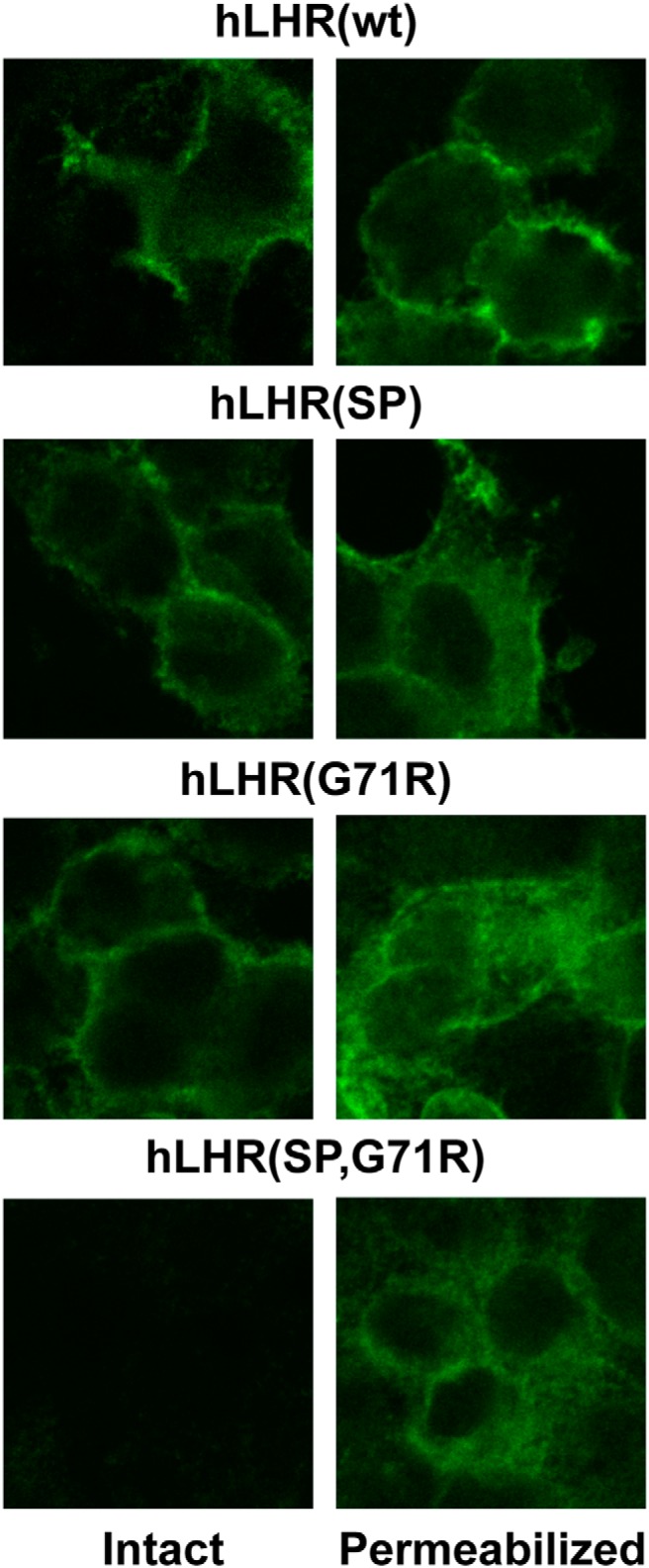

To ensure that the results examining efficacy of hCG-stimulated cAMP production were not an artifact of transiently transfected cells, we also examined basal and hCG-stimulated cAMP production in stably transfected HEK293 cells. Because our goal was to compare hCG-stimulated cAMP under conditions where cell surface receptor densities were comparable, varying plasmid concentrations were used and cell lines with closely matched cell surface receptor expression as determined by 125I-hCG binding were used. As shown in Figure 6A, we achieved a very tight match of cell surface 125I-hCG binding in hLHR(wt) and hLHR(SP,G71R) cells, whereas hLHR(SP) and hLHR(G71R) cells had approximately 2- to 3-fold higher binding. Basal levels of cAMP mirrored cell surface binding activity, with wt and SP,G71R cells exhibiting comparable basal cAMP levels and SP and G71R cells exhibiting somewhat higher cAMP levels (Figure 6B). Notably, the cell lines expressing each of the 3 hLHR mutants responded to hCG with at least 10-fold greater levels of cAMP than cells expressing hLHR(wt), consistent with increased efficacy of the mutants. Although the interpretation of the SP and G71R cells is not unambiguous due to their having higher 125I-hCG binding than wt cells, a comparison of SP,G71R cells and wt cells, which have the same cell surface binding activities, unambiguously demonstrates the increased efficacy of hCG-stimulated cAMP in hLHR(SP,G71R) and validates the observations made with transiently transfected cells. The same stably transfected cell lines were also examined by immunofluorescence to evaluate cell surface and intracellular receptor expression. As would be expected, in both intact and permeabilized cells, the wt hLHR localized predominantly to cell surface (Figure 7). Intact hLHR(SP) and hLHR(G71R) cells each exhibited cell surface localization. However, when permeabilized, the hLHR(SP) and hLHR(G71R) cells each revealed a significant amount of receptor to be localized intracellularly. Under the same experimental conditions, little or no immunofluorescence was detected in intact hLHR(SP,G71R) cells. However, when SP,G71R cells were permeabilized, the SP,G71R mutant was readily detected intracellularly. These results suggest that the reduced cell surface expression of the SP, G17R, and SP,G71R mutants is due at least in part to intracellular retention of the mutants. Furthermore, using an immunological means of receptor detection, the data in Figure 8 indicate similar cell surface receptor levels in hLHR(SP), hLHR(G71R), and hLHR(wt) cell lines, and reduced levels of cells surface receptor expression in the hLHR(SP,G71R) hLHR(G71R) cell line. Nonetheless, each of the cell lines expressing mutant receptors exhibited 11- to 13-fold greater hCG-stimulated cAMP than hLHR(wt) cells (Figure 6). These data further support the notion that the SP, G71R, and SP,G71R mutants exhibit increased efficacy for hCG-stimulated cAMP relative to wt receptor.

Figure 6.

Cells stably expressing the patient's hLHR mutants exhibit greater efficacies of hCG-stimulated cAMP relative to hLHR(wt). HEK293 cells stably expressing myc-hLHR(wt), myc-hLHR(SP), myc-hLHR(G71R), or myc-hLHR(SP,G71R), generated using plasmid concentrations designed to yield similar cell surface receptor expression, were assayed for maximal cell surface 125I-hCG binding (A), basal cAMP (B), and cAMP in response to a saturating concentration of hCG (C). Data shown are the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments.

Figure 7.

Immunolocalization of hLHR in stably transfected cells reveals intracellular retention of the patient's hLHR mutants. hLHR protein was visualized by immunofluorescence using anti-myc antibody in intact or permeabilized HEK293 cells stably expressing myc-hLHR(wt), myc-hLHR(SP), myc-hLHR(G71R), or myc-hLHR(SP,G71R), generated using plasmid concentrations designed to yield similar cell surface receptor expression.

Figure 8.

Increased efficacy for hCG-stimulated cAMP of the patient's hLHR mutants is not an artifact of the myc-epitope tag, and it is observed with other ectodomain, but not serpentine domain, hLHR mutants. A and B, HEK293 cells were transfected with varying concentrations of plasmids encoding hLHR(wt), the ectomain mutant hLHR(SP,G71R), the ectomain mutant hLHR(V114F), or the serpentine mutant hLHR(S616Y). C and D, HEK293 cells were transfected with hLHR(wt), the ectomain mutant hLHR(F194V), or the serpentine domain mutant hLHR(A593P). Relative cell surface receptor expression was determined by maximal 125I-hCG binding to intact cells, and cAMP responses to a maximally stimulating concentration of hCG were determined. Data points are the mean ± SD of triplicate determinations from 1 experiment representative of 3 independent experiments. Top panels, All data points are shown. Bottom panels, The region shaded in gray in the corresponding top panel has been expanded.

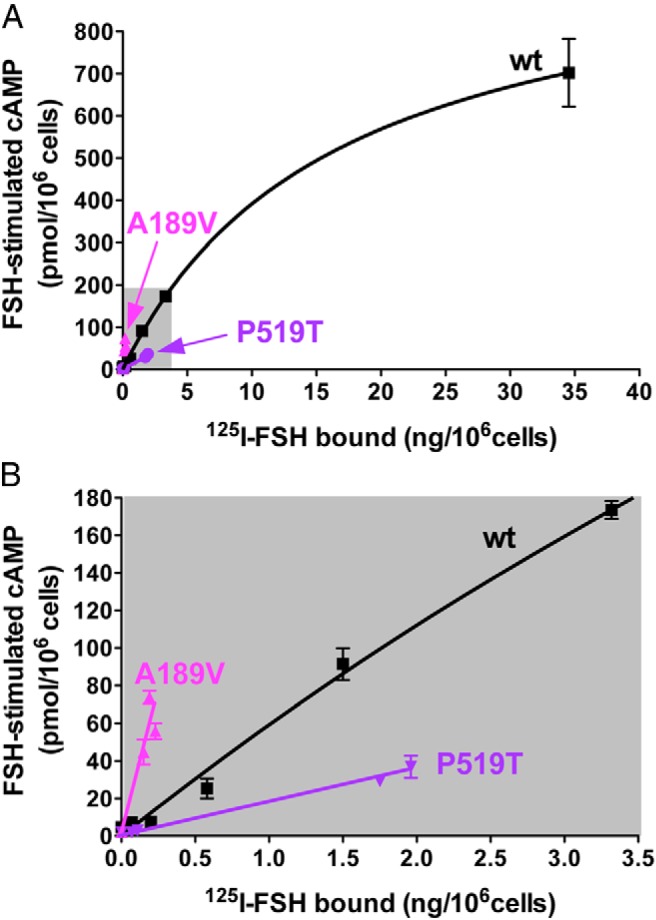

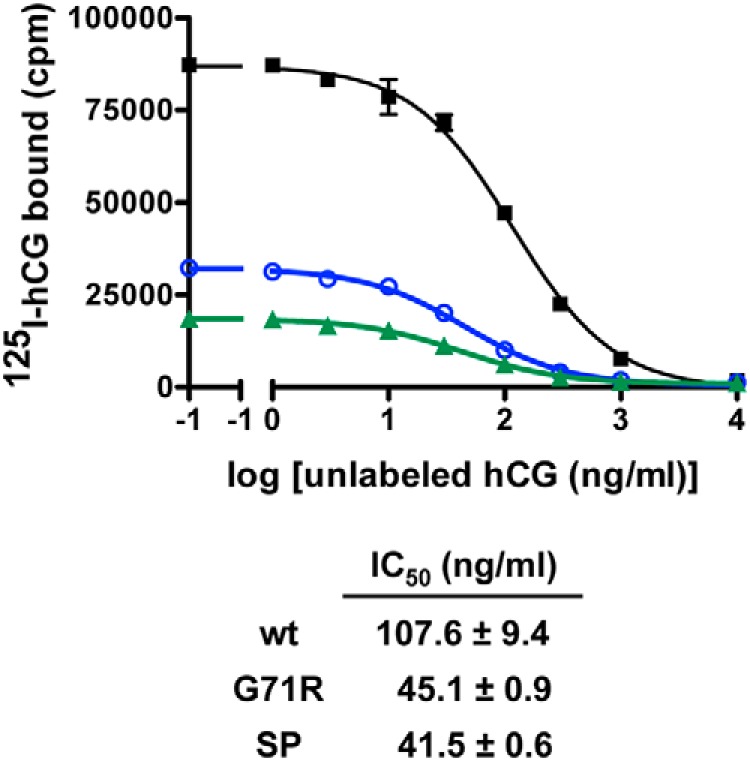

All experiments examining receptor efficacy performed thus far were performed using recombinant hLHR proteins containing a myc epitope tag immediately upstream of the predicted N terminus of hLHR(wt). Given that the signal peptide cleavage computations suggest that hLHR(SP) and hLHR(SP,G71R) have a different N terminus than hLHR(wt), we considered whether the myc epitope tag on the SP and SP,G71R mutants might affect their expression and/or behavior. Furthermore, given that increased efficacy for hCG-stimulated cAMP was observed with 3 different hLHR mutants (SP, G71R, and SP,G71R), we sought to determine how specific this phenomenon was. Towards this end, we chose to examine other naturally occurring mutations that were shown to decrease cell surface expression. These included the ectodomain mutants V114F (33) and F194V (34) and the serpentine domain mutants A593P (13, 15, 35, 36) and S616Y (13, 15, 37, 38). Because cell surface expression could no longer be ascertained by myc-dependent flow cytometry, cell surface expression was quantified by specific binding of a saturating concentration of 125I-hCG to intact cells. The resulting data (Figure 8) demonstrate that the presence or absence of the myc epitope tag does not influence the results because untagged hLHR(SP,G71R) also exhibited increased efficacy for hCG-stimulated cAMP production. The increased efficacy of hLHR(SP,G71R) relative to hLHR(wt) in Figure 8 also demonstrates that similar results are observed regardless of whether cell surface receptor numbers are quantified by the binding of a saturating concentration of labeled hormone or, as was done in Figure 3, by flow cytometry. Strikingly, the data also revealed increased efficacy of hCG-stimulated Gs in the ectodomain hLHR mutants but not the serpentine domain hLHR mutants. To determine whether this phenomenon was unique to the hLHR or might be shared by other structurally similar GPCRs, we examined the closely related hFSHR. The efficacy of FSH-stimulated cAMP was evaluated as a function of cell surface FSHR density (as determined by 125I-FSH binding) for hFSHR(wt), the ectodomain mutant hFSHR(A189V) (39), and the serpentine mutant hFSHR(P519T) (40). A comparison of FSH-stimulated cAMP by the mutants and hFSHR(wt) at comparable cell surface receptor levels reveals increased efficacy of the hFSHR ectodomain mutant but not the serpentine mutant (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Increased efficacy for FSH-stimulated cAMP is observed with an FSHR ectodomain, but not serpentine, domain mutation. HEK293 cells were transfected with varying concentrations of plasmids encoding hFSHR(wt), the ectomain mutant hLHR(A189V), or the serpentine mutant hFSHR(P619T). Relative cell surface receptor expression was determined by maximal 125I-FSH binding to intact cells and cAMP responses to a maximally stimulating concentration of FSH were determined. Data points are the mean ± SD of triplicate determinations from 1 experiment representative of 3 independent experiments. Top panel, All data points are shown. Bottom panel, The region shaded in gray in the top panel has been expanded.

Our data suggest that misfolding mutations in the ectodomain, but not the serpentine domain, of the gonadotropin receptors that cause intracellular retention and decreased cell surface receptor expression are associated with increased intrinsic signaling efficacy of the receptor mutants. One possible cause, at least in part, for the increased efficacy is that the mutants may possess increased hormone binding affinities. Although the cell surface receptor expression levels SP,G71R and most other mutants were too low to permit accurate determinations of hormone binding affinities, hCG binding affinities for hLHR(G71R) and hLHR(SP) were possible to ascertain. For both of these ectodomain mutants, an approximate 2.5-fold decrease in IC50 relative to hLHR(wt) was observed (Figure 10), indicating increased binding affinities by these mutants for hCG.

Figure 10.

The SP and G71R mutations increase the binding affinity of the hLHR for hCG. HEK293 cells were transfected with the same maximal concentration of plasmid expressing either myc-hLHR(wt), myc-hLHR(G71R), or myc-hLHR(SP), and the relative binding affinities of hCG were determined by competition binding assays. Cells were incubated with a trace concentration of 125I-hCG with no additions (NA) or with the addition of increasing concentrations of unlabeled hCG. Data points are the mean ± range of duplicate determinations from 1 experiment representative of 2 independent experiments. The table below depicts the mean ± range of the Kis determined from 2 experiments.

Discussion

The data presented demonstrate the presence of 2 homozygous LHCGR mutations, one occurring in the signal peptide and a G71R mutation also occurring in the ectodomain, in a patient with severe LH resistance causing Leydig cell hypoplasia. Characterization of these 2 ectodomain mutations, alone and in combination, revealed decreased cell surface receptor expression due to intracellular retention of the mutant receptors. This is not surprising given that it is well documented that misfolding mutations of the gonadotropin receptors, regardless of whether they are localized to the ectodomain or serpentine domain, result in decreased cell surface expression due the retention of misfolded proteins in the ER by the cell's quality control system (3, 12, 41, 42). Remarkably, however, the studies presented here revealed that the very low densities of mutant receptors corresponding to the patient's mutations exhibited increased intrinsic signaling efficacy with respect to hCG-stimulated cAMP synthesis when compared with wt hLHR at similarly decreased cell surface densities. A comparison of the cell surface expression and hormone-stimulated activities of misfolding mutations in the ectodomain vs. the serpentine domain of the hLHR, revealed that increased agonist efficacy is associated only with misfolding mutations in the ectodomain. This same pattern was observed in misfolding mutations of the hFSHR, suggesting an underlying mechanism that is common to the gonadotropin receptors.

Numerous loss-of-function mutations of the LHCGR have been reported in patients with severe LH resistance leading to Leydig cell hypoplasia (3, 4). Similar to other GPCRs, most loss-of-function hLHR mutations cause misfolding of the receptor, leading to its intracellular retention and reduced cell surface expression (3, 4, 12, 43). The homozygous G71R mutation identified in this patient is a novel point mutation that occurs within the second exon of the LHCGR. This substitution alone results in a substantial reduction in cell surface receptor expression due, at least in part, to intracellular retention of the mutant. Notably, however, the reduced numbers of hLHR(G71R) mutant receptors on the cell surface exhibit an increased efficacy for hCG-stimulated cAMP synthesis. As such, maximal hCG-stimulated cAMP by hLHR(G71R) is greater than that of hLHR(wt) when expressed at comparable low cell surface densities.

The other homozygous mutation observed in this patient is a 27-bp insertion mutation (p.Gln18_Leu19ins9; designated as SP here) that occurs after nucleotide 54 within exon 1 of the LHCGR. When expressed singly, the SP mutation also resulted in decreased cell surface receptor expression. Strikingly, cells expressing SP mutant receptors also exhibited increased efficacy for hCG-stimulated cAMP compared with cells with similar low densities of hLHR(wt). Nucleotide 54 of the LHCGR resides within a region encoding what is predicted to be the signal peptide sequence for the hLHR. It is important to note that only in the rat LHR has it been possible to generate sufficient amounts of purified receptor to permit the experimental determination of the N-terminal sequence of the mature receptor by protein sequencing (28) and thereby know with certainty the cleavage site of the signal peptide. In contrast, for all other glycoprotein hormone receptors of different species and the 5%–10% of other GPCRs containing signal peptides, the cleavage site of the signal peptide and therefore the N-terminal sequence of the mature receptor protein can only be deduced by computer algorithms (29). Using SignalP 4.1 (32), hLHR(wt), and hLHR(SP) are predicted to yield mature receptor proteins with different N-terminal sequences (Figure 5). Furthermore, the signal peptide sequence, which before its cleavage mediates the ER targeting/insertion process (44, 45), is altered as well. The decreased cell surface expression of hLHRs containing the SP mutation may, therefore, be attributable to altered properties of the signal peptide sequence that do not efficiently mediate ER targeting/insertion and/or to misfolding of the mature receptor due to the predicted changes in the extreme N terminus of the mature protein. Interestingly, the LHCGR has a propensity for insertion polymorphisms and mutations after nucleotide 54 (48–51). Thus, about 30% of the Caucasian population expresses a polymorphic variant of the LHCGR in which 6 bp have been inserted in-frame after nucleotide 54, resulting in the insertion (duplication) of the residues LQ (Figure 5) (49–51). No alterations in overt differences in the reproductive phenotypes of individuals with vs without the LQ polymorphism have been observed. These findings are consistent with the predicted cleavage of the LQ polymorphic variant that would yield an N terminus of the mature protein identical to that of hLHR(wt) lacking the LQ insertion (Figure 5). Notably, rare mutations of the LHCGR associated with Leydig cell hypoplasia have been identified in which a longer in-frame insertion occurred after nucleotide 54 (p.Gln18_Leu19ins11) (48, 49). Thus, 2 groups independently reported patients harboring compound heterozygous loss-of-function mutations of the LHCGR where one of the mutations was a 33-bp in-frame insertion (relative the hLHR(wt) without the LQ polymorphism) after nucleotide 54 (48, 49). An intriguing aspect of the insertions at nucleotide 54, as first noted by Richter-Unruh et al (49), is that both the polymorphism and longer mutation inserts at this site (including the 27-bp mutational insert described here) appear to contain a short imperfect polyleucine triplet repeat and therefore bear a resemblance to other disorders arising from the expansion of unstable nucleotide repeats (52). Heterologous cells expressing recombinant hLHR with the 33-bp insertion mutation were characterized by Wu et al (48). Their findings indicated little or no detectable binding of 125I-hCG to intact cells or detergent extracts and little or no detectable hCG-stimulated cAMP, suggesting a lack of expression of the mutant receptor and/or lack of hCG binding activity. These findings differ significantly from our characterization of the 27-bp insertion mutant hLHR(SP) described here where, in spite of reduced cell surface expression, cells expressing the SP mutant exhibited detectable hCG binding activity hCG-stimulated cAMP production with increased efficacy relative to wt receptor. It is important to note, however, that these 2 signal peptide insertions result in different alterations to the amino acid sequences of their respective mature proteins at the N terminus (see Figure 5). We speculate that the mature protein resulting from the 33-bp signal peptide insertion may cause greater misfolding and intracellular retention of that mutant, and therefore less cell surface receptor expression, than the 27-bp insertion, thus causing cells expressing the 33-bp insertion mutant to have little or no overall hormone responsiveness. It is also possible that methodological differences contribute as well. Maximal hCG binding activity was assessed by Wu et al (48) using only a trace concentration of 125I-hCG and thus would not have readily detected reduced levels of binding. Similarly, the cAMP assay used in the earlier study was relatively insensitive, detecting only a 4-fold increase in hCG-stimulated cAMP in cells expressing hLHR(wt). In contrast, the cAMP assay used here detects approximately 1000-fold increase in hCG-stimulated cAMP in hLHR(wt) cells.

Given the unusual observation that both the SP and G71R mutations (as well as the combined SP,G71R mutation) each resulted in decreased cell surface receptor expression coupled with increased signaling efficacy, other naturally occurring mutations of the hLHR reported to cause decreased cell surface expression were examined for their signaling efficacies. Consistently, we observed that mutations in the hLHR ectodomain, but not the serpentine domain, were associated with increased efficacy for hCG-stimulated cAMP production. Therefore, the increased efficacies of the 2 mutations identified in our patient are not unique, but rather reflect a more generalized pattern whereby misfolding mutations in the hLHR ectodomain (as defined by mutations yielding decreased cell surface receptor expression) exhibit increased signaling efficacies. Our studies further showed that a naturally occurring misfolding mutation in the ectodomain, but not serpentine domain, of the hFSHR, similarly caused increased signaling efficacy. These data suggest that the phenomenon of increased signaling efficacy caused by misfolding mutations of the ectodomain is not restricted to the hLHR, but rather it is a shared feature of the gonadotropin receptors. It remains to be determined whether the TSH receptor, the other member of the glycoprotein hormone receptor family of GPCRs, shares this property as well.

Typically, one thinks of signaling efficacy in the context of different agonists for a given GPCR having varying efficacies (ie, eliciting different maximal responses), with the greatest responses elicited by full agonists and lesser responses by partial agonists (53, 54), with each stabilizing the serpentine domain in different GPCR conformational landscapes (54, 55). In contrast, in the present situation, increased efficacies of the hLHR and hFSHR for hormone-stimulated cAMP were induced by mutations in the receptor, specifically in the ectodomain. although not unheard of (see for example Refs. 56, 57), mutations in GPCRs that alter agonist efficacy are much more unusual. Although the low levels of cell surface expression precluded the ability to measure binding affinities in most of the mutants, we did observe increased hCG binding affinities for hLHR(SP) and hLHR(G71R). Furthermore, previous studies of ours showed that an ectodomain misfolding hLHR mutant of laboratory design, I80A, exhibited increased signaling efficacy and increased hCG binding affinity (26). If these and the other ectodomain mutants described here were to have increased hormone binding affinities, it is most likely achieved by allosteric mechanisms rather than by each mutation directly altering a site involved in hormone binding. Indeed, the predicted structural model for the ectodomain of hLHR(G71R) shown in Figure 4 clearly precludes this mutation as being within a region directly involved in hormone binding. Nor is the extreme N terminus of the FSHR, which the SP mutation alters, directly involved in hormone binding (6). Interestingly, the argument has been put forth that measurements of hormone binding affinities to GPCRs are mathematically “contaminated” by efficacy and that it may be not possible to fully separate these 2 parameters (58). Therefore, although we can conclude that the misfolding ectodomain mutants of the gonadotropin receptors mutants have increased efficacy for hCG stimulation of cAMP synthesis, we cannot rule out the possibility that observed increases in apparent binding affinities may reflect increased efficacies of the receptors.

Clearly, the many disparate misfolding mutations of the gonadotropin within the ectodomain that result in decreased cell surface receptor expression due to intracellular retention, including the 2 mutations identified in the patient here, must provoke common alterations in the structural organization of the receptor such that each of these different mutations causes the cell surface mutant receptors to have increased efficacy with respect to agonist-stimulated cAMP production. This alteration in intrinsic receptor signaling activity is specific for the agonist-occupied receptor, because basal activities were unaltered (data not shown). Although the precise mechanisms underlying increased efficacy for agonist signaling of misfolding ectodomain gonadotropin receptor mutants have not yet been elucidated, there are several possibilities to consider. One may be that misfolding ectomain mutations disrupt gonadotropin receptor dimerization/oligomerization. The hLHR and FSHR have each been shown to self-associate into dimers and possibly higher ordered oligomers (8–11, 59). This process is initiated in the ER and is mediated by interactions occurring between both the serpentine domains and the ectodomains (8, 9). Similar to GPCRs in general (10, 60–66), dimers of hLHR and hFSHR each exhibit negative cooperativity with respect to agonist binding (8, 9). Therefore, by potentially disrupting dimerization, misfolding ectodomain mutations of the gonadotropin receptors may cause increased agonist binding affinity. With respect specifically to glycoprotein hormone receptors, recent studies by Jiang et al on the crystallization of the entire ectodomain of the FSHR complexed with FSH suggested a trimeric arrangement of the FSH-bound FSHR ectodomain (7, 11). Their studies further suggested that normally 1 hormone molecule binds to and activates the trimeric receptor. However, mutations of FSH predicted to disrupt the trimeric interface in the receptor ectodomains increased agonist efficacy presumably by enabling additional FSH molecules to bind. Therefore, disruption of gonadotropin hormone receptor complexes by misfolding mutations in the ectodomain may increase efficacy of agonist activation of the receptor by a similar mechanism. Additionally, one may consider the role of a sulfated tyrosine residue (sTyr site) in the hinge region of the glycoprotein hormone receptor that was demonstrated by Costagliola and coworkers (67) and Costagliola et al (68) to be critical for glycoprotein hormone activation. Based upon their crystollagraphic data, Jiang et al have proposed a 2-step process for recognition of a glycoprotein hormone by its receptor and the consequent receptor activation (7). Their model postulates that initially hormone binds to the inner concave surface of leucine-rich repeats 1–8. This high-affinity interaction then causes a structural change in the receptor ectodomain that lifts the sTyr site and thus enables it to dock with the bound hormone, thereby promoting receptor activation. Interestingly, mutations in FSH predicted to lift the sTyr-harboring loop of the FSHR exhibited increased efficacy of receptor activation (7). Therefore, one may also consider whether misfolding ectodomain mutations in the gonadotropin receptors allosterically cause an increased flexibility of the receptor's sTyr-harboring loop, thereby promoting an increased probability of docking of the sTyr site onto the bound hormone. Future studies are warranted to elucidate the structural basis for the observed increased efficacy of agonist activation of gonadotropin receptors induced by misfolding mutations of the ectodomain.

Our studies suggest that misfolding ectodomain mutations of the gonadotropin receptors result in decreased cell surface expression, but increased efficacy for agonist stimulation of the small numbers of receptors on the plasma membrane. From a physiological perspective, the pathophysiologies associated with these mutations result from reduced or absent gonadal cell responsiveness to hormone and are therefore attributable to reduced or absent cell surface receptor expression. However, because misfolded gonadotropin receptor mutants possess increased intrinsic agonist efficacy relative to wt receptor, a relatively small increase or decrease in their cell surface receptor expression would have a much greater impact on gonadal responsiveness to hormone than the same relative change in cell surface receptor expression of wt receptor. Therefore, gonadal cells expressing misfolding ectodomain mutants are even more exquisitely dependent upon cell surface receptor number than wt receptor or other types of loss-of-function mutations. We and others have shown that misfolded gonadotropin receptors that are retained intracellularly can be functionally rescued by membrane-permeable allosteric ligands that enable a greater percentage of mutant receptor to be trafficked to the plasma membrane (13, 69). Therefore, when considering potential therapeutic interventions, it should be considered that the hormone responsiveness of gonadal cells expressing a misfolding ectodomain gonadotropin receptor mutant that are treated with a pharmacoperone is likely to be greater than that of similarly treated cells expressing a misfolding serpentine domain mutation that is rescued/trafficked to the plasma membrane to the same extent.

In summary, the characterization of LHCGR mutations in a patient with Leydig cell hypoplasia led to the unexpected discovery that ectodomain misfolding mutations of the hLHR and FSHR display increased efficacy for hormone stimulation. Our findings are of significance to our understanding of the mechanisms underlying hormone-stimulated gonadotropin receptor activation as well as to our understanding of and potential treatment of the pathophysiologies resulting from misfolding gonadotropin receptor mutations.

Additional material

Supplementary data supplied by authors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the University of Athens Medical School, Athens, Greece (E.C., G.P.C., A.C.S.), Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento Científico Tecnológico–CNPq grants (A.C.L.), and the National Institutes of Health Grant HD022196 (to D.L.S.). Procurement of flow cytometry data reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health Award P30CA086862.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- FSHR

- FSH receptor

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- hCG

- human chorionic gonadotropin

- LHR

- lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor

- PBS-IH

- PBS for immunohistochemistry

- PBS-IH/BSA

- PBS-IH containing 0.5% BSA

- wt

- wild type.

References

- 1. Ascoli M, Fanelli F, Segaloff DL. The lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor, a 2002 perspective. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:141–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vassart G, Pardo L, Costagliola S. A molecular dissection of the glycoprotein hormone receptors. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Segaloff DL. Diseases associated with mutations of the human lutropin receptor. Progr Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2009;89C:97–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Piersma D, Verhoef-Post M, Berns EM, Themmen AP. LH receptor gene mutations and polymorphisms: an overview. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2007;260–262:282–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Arnhold IJ, Lofrano-Porto A, Latronico AC. Inactivating mutations of luteinizing hormone β-subunit or luteinizing hormone receptor cause oligo-amenorrhea and infertility in women. Horm Res. 2009;71:75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fan QR, Hendrickson WA. Structure of human follicle-stimulating hormone in complex with its receptor. Nature. 2005;433:269–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jiang X, Liu H, Chen X, et al. Structure of follicle-stimulating hormone in complex with the entire ectodomain of its receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:12491–12496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guan R, Feng X, Wu X, et al. Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer studies reveal constitutive dimerization of the human lutropin receptor and a lack of correlation between receptor activation and the propensity for dimerization. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:7483–7494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guan R, Wu X, Feng X, Zhang M, Hébert TE, Segaloff DL. Structural determinants underlying constitutive dimerization of unoccupied human follitropin receptors. Cell Signal. 2010;22:247–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Urizar E, Montanelli L, Loy T, et al. Glycoprotein hormone receptors: link between receptor homodimerization and negative cooperativity. EMBO J. 2005;24:1954–1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jiang X, Fischer D, Chen X, et al. Evidence for follicle-stimulating hormone receptor as a functional trimer. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:14273–14282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vassart G, Costagliola S. G protein-coupled receptors: mutations and endocrine diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7:362–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Newton CL, Whay AM, McArdle CA, et al. Rescue of expression and signaling of human luteinizing hormone G protein-coupled receptor mutants with an allosterically binding small-molecule agonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:7172–7176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ascoli M, Puett D. Gonadotropin binding and stimulation of steroidogenesis in Leydig tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:99–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mizrachi D, Segaloff DL. Intracellularly located misfolded glycoprotein hormone receptors associate with different chaperone proteins than their cognate wild-type receptors. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:1768–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang M, Tao YX, Ryan GL, Feng X, Fanelli F, Segaloff DL. Intrinsic differences in the response of the human lutropin receptor versus the human follitropin receptor to activating mutations. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25527–25539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eswar N, Eramian D, Webb B, Shen MY, Sali A. Protein structure modeling with MODELLER. Meth Mol Biol. 2008;426:145–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang M, Mizrachi D, Fanelli F, Segaloff DL. The formation of a salt bridge between helices 3 and 6 Is responsible for the constitutive activity and lack of hormone responsiveness of the naturally occurring L457R mutation of the human lutropin receptor. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:26169–26176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zoenen M, Urizar E, Swillens S, Vassart G, Costagliola S. Evidence for activity-regulated hormone-binding cooperativity across glycoprotein hormone receptor homomers. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang H, Jaquette J, Collison K, Segaloff DL. Positive charges in a putative amphiphilic helix in the carboxyl-terminal region of the third intracellular loop of the luteinizing hormone/chorionic gonadotropin receptor are not required for hormone-stimulated cAMP production but are necessary for expression of the receptor at the plasma membrane. Mol Endocrinol. 1993;7:1437–1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Latronico AC, Abell AN, Arnhold IJ, et al. A unique constitutively activating mutation in third transmembrane helix of luteinizing hormone receptor causes sporadic male gonadotropin-independent precocious puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:2435–2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Latronico AC, Chai Y, Arnhold IJ, Liu X, Mendonca BB, Segaloff DL. A homozygous microdeletion in helix 7 of the luteinizing hormone receptor associated with familial testicular and ovarian resistance is due to both decreased cell surface expression and impaired effector activation by the cell surface receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:442–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shinozaki H, Fanelli F, Liu X, Jaquette J, Nakamura K, Segaloff DL. Pleiotropic effects of substitutions of a highly conserved leucine in transmembrane helix III of the human lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor with respect to constitutive activation and hormone responsiveness. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:972–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tao YX, Abell AN, Liu X, Nakamura K, Segaloff DL. Constitutive activation of G protein-coupled receptors as a result of selective substitution of a conserved leucine residue in transmembrane helix III. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:1272–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang M, Guan R, Segaloff DL. Revisiting and questioning functional rescue between dimerized LH receptor mutants. Mol Endocrinol. 2012;26:655–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fan QR, Hendrickson WA. Assembly and structural characterization of an authentic complex between human follicle stimulating hormone and a hormone-binding ectodomain of its receptor. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2007;260–262:73–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McFarland KC, Sprengel R, Phillips HS, et al. Lutropin-choriogonadotropin receptor: an unusual member of the G protein-coupled receptor family. Science. 1989;245:494–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schülein R, Westendorf C, Krause G, Rosenthal W. Functional significance of cleavable signal peptides of G protein-coupled receptors. Eur J Cell Biol. 2012;91:294–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nielsen H, Engelbrecht J, Brunak S, von Heijne G. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 1997;10:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, von Heijne G, Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:783–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat Methods. 2011;8:785–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Richter-Unruh A, Verhoef-Post M, Malak S, Homoki J, Hauffa BP, Themmen AP. Leydig cell hypoplasia: absent luteinizing hormone receptor cell surface expression caused by a novel homozygous mutation in the extracellular domain. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:5161–5167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gromoll J, Schulz A, Borta H, et al. Homozygous mutation within the conserved Ala-Phe-Asn-Glu-Thr motif of exon 7 of the LH receptor causes male pseudohermaphroditism. Eur J Endocrinol. 2002;147:597–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kremer H, Kraaij R, Toledo SP, et al. Male pseudohermaphroditism due to a homozygous missense mutation of the luteinizing hormone receptor gene. Nat Genet. 1995;9:160–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Toledo SP, Brunner HG, Kraaij R, et al. An inactivating mutation of the luteinizing hormone receptor causes amenorrhea in a 46,XX female. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:3850–3854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Laue LL, Wu SM, Kudo M, et al. Compound heterozygous mutations of the luteinizing hormone receptor gene in Leydig cell hypoplasia. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:987–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Latronico AC, Anasti J, Arnhold IJ, et al. Brief report: testicular and ovarian resistance to luteinizing hormone caused by homozygous inactivating mutations of the luteinizing hormone receptor gene. New Engl J Med. 1996;334:507–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Doherty E, Pakarinen P, Tiitinen A, et al. A novel mutation in the FSH receptor inhibiting signal transduction and causing primary ovarian failure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1151–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Meduri G, Touraine P, Beau I, et al. Delayed puberty and primary amenorrhea associated with a novel mutation of the human follicle-stimulating hormone receptor: clinical, histological, and molecular studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:3491–3498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Themmen AP. An update of the pathophysiology of human gonadotrophin subunit and receptor gene mutations and polymorphisms. Reproduction. 2005;130:263–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tao YX, Segaloff DL. Follicle stimulating hormone receptor mutations and reproductive disorders. Progr Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2009;89C:115–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Conn PM, Ulloa-Aguirre A, Ito J, Janovick JA. G protein-coupled receptor trafficking in health and disease: lessons learned to prepare for therapeutic mutant rescue in vivo. Pharmacol Rev. 2007;59:225–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Higy M, Junne T, Spiess M. Topogenesis of membrane proteins at the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochemistry. 2004;43:12716–12722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wallin E, von Heijne G. Properties of N-terminal tails in G-protein coupled receptors: a statistical study. Protein Eng. 1995;8:693–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rutz C, Renner A, Alken M, et al. The corticotropin-releasing factor receptor type 2a contains an N-terminal pseudo signal peptide. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24910–24921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Schulz K, Rutz C, Westendorf C, et al. The pseudo signal peptide of the corticotropin-releasing factor receptor type 2a decreases receptor expression and prevents Gi-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:32878–32887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wu SM, Hallermeier KM, Laue L, et al. Inactivation of the luteinizing hormone/chorionic gonadotropin receptor by an insertional mutation in Leydig cell hypoplasia. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:1651–1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Richter-Unruh A, Martens JW, Verhoef-Post M, et al. Leydig cell hypoplasia: cases with new mutations, new polymorphisms and cases without mutations in the luteinizing hormone receptor gene. Clin Endocrinol. 2002;56:103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wu SM, Jose M, Hallermeier K, Rennert OM, Chan WY. Polymorphisms in the coding exons of the human luteinizing hormone receptor gene. Mutations in brief no. 124. Online. Hum Mutat. 1998;11:333–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tsai-Morris CH, Geng Y, Buczko E, Dehejia A, Dufau ML. Genomic distribution and gonadal mRNA expression of two human luteinizing hormone receptor exon 1 sequences in random populations. Hum Hered. 1999;49:48–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Orr HT, Zoghbi HY. Trinucleotide repeat disorders. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:575–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kenakin T. Efficacy at G-protein-coupled receptors. Nat Rev Drug Disc. 2002;1:103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kobilka BK, Deupi X. Conformational complexity of G-protein-coupled receptors. Tr Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:397–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kofuku Y, Ueda T, Okude J, et al. Efficacy of the β(2)-adrenergic receptor is determined by conformational equilibrium in the transmembrane region. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Seibt BF, Schiedel AC, Thimm D, Hinz S, Sherbiny FF, Müller CE. The second extracellular loop of GPCRs determines subtype-selectivity and controls efficacy as evidenced by loop exchange study at A2 adenosine receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85:1317–1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Beinborn M, Ren Y, Bläker M, Chen C, Kopin AS. Ligand function at constitutively active receptor mutants is affected by two distinct yet interacting mechanisms. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:753–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Strange PG. Agonist binding, agonist affinity and agonist efficacy at G protein-coupled receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:1353–1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Thomas RM, Nechamen CA, Mazurkiewicz JE, Muda M, Palmer S, Dias JA. Follice-stimulating hormone receptor forms oligomers and shows evidence of carboxyl-terminal proteolytic processing. Endocrinology. 2007;148:1987–1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Suzuki Y, Moriyoshi E, Tsuchiya D, Jingami H. Negative cooperativity of glutamate binding in the dimeric metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:35526–35534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. El-Asmar L, Springael JY, Ballet S, Andrieu EU, Vassart G, Parmentier M. Evidence for negative binding cooperativity within CCR5-CCR2b heterodimers. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:460–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Springael JY, Urizar E, Costagliola S, Vassart G, Parmentier M. Allosteric properties of G protein-coupled receptor oligomers. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;115:410–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Svendsen AM, Zalesko A, Kønig J, et al. Negative cooperativity in H2 relaxin binding to a dimeric relaxin family peptide receptor 1. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;296:10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Comps-Agrar L, Kniazeff J, Nørskov-Lauritsen L, et al. The oligomeric state sets GABA(B) receptor signalling efficacy. EMBO J. 2011;30:2336–2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ferré S, Casadó V, Devi LA, et al. G protein-coupled receptor oligomerization revisited: functional and pharmacological perspectives. Pharmacol Rev. 2014;66:413–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Sohy D, Yano H, de Nadai P, et al. Hetero-oligomerization of CCR2, CCR5, and CXCR4 and the protean effects of “selective” antagonists. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:31270–31279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Bonomi M, Busnelli M, Persani L, Vassart G, Costagliola S. Structural differences in the hinge region of the glycoprotein hormone receptors: evidence from the sulfated tyrosine residues. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:3351–3363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Costagliola S, Panneels V, Bonomi M, et al. Tyrosine sulfation is required for agonist recognition by glycoprotein hormone receptors. EMBO J. 2002;21:504–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Janovick JA, Maya-Nunez G, Ulloa-Aguirre A, et al. Increased plasma membrane expression of human follicle-stimulating hormone receptor by a small molecule thienopyr(im)idine. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;298:84–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.