Abstract

Phosphoglucomutase 3 (PGM3) is an enzyme converting N-acetyl-glucosamine-6-phosphate to N-acetyl-glucosamine-1-phosphate, a precursor important for glycosylation. Mutations in the PGM3 gene have recently been identified as the cause of novel primary immunodeficiency with a hyper-IgE like syndrome. Here we report the occurrence of a homozygous mutation in the PGM3 gene in a family with immunodeficient children, described already in 1976. DNA from two of the immunodeficient siblings was sequenced and shown to encode the same homozygous missense mutation, causing a destabilized protein with reduced enzymatic capacity. Affected individuals were highly prone to infections, but lack the developmental defects in the nervous and skeletal systems, reported in other families. Moreover, normal IgE levels were found. Thus, belonging to the expanding group of congenital glycosylation defects, PGM3 deficiency is characterized by immunodeficiency, with or without increased IgE levels, and with variable forms of developmental defects affecting other organ systems.

Abbreviations: CDG, Congenital defects in glycosylation; EBV, Epstein Barr Virus.; GlcNAc-1-P, N-acetyl-glucosamine-1-phosphate.; GlcNAc-6-P, N-acetyl-glucosamine-6-phosphate; HIES, hyper-IgE syndrome; PGM3, Phosphoglucomutase 3; UDP-GalNac, uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine

Keywords: Primary immunodeficiency, N-acetylglucosamine-phosphate mutase, hyper-IgE syndrome, Congenital defects of glycosylation, CDG

Highlights

-

•

Immunodeficiency reported in 1976, is now identified as caused by a mutation in PGM3.

-

•

Replacing Ile322 with Thr reduces protein stability and enzyme activity in PGM3.

-

•

Identified mutation in PGM3 induces primary immunodeficiency without hyper-IgE.

-

•

A PGM3-PID with increased eosinophils but without skeletal or neurological changes

1. Introduction

Phosphoglucomutase 3 (PGM3), previously known as N-acetylglucosamine-phosphate mutase (AGM1) [1], is an enzyme important for posttranslational glycosylation. This enzyme converts N-acetyl-glucosamine-6-phosphate (GlcNAc-6-P) to N-acetyl-glucosamine-1-phosphate (GlcNAc-1-P), which is needed to synthesize uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GalNac). The latter is an important building block for both N-linked and O-linked glycans, as well as for glycolipids [2]. The O-GlcNAcylation of proteins is very sensitive to UDP-GlcNAc concentrations [3], and might thus be seriously disturbed by reduced PGM3 activity. It is suggested that O-GlcNAcylation can modulate cellular signaling and influence transcription regulatory pathways in response to nutrients and stress [4], [5]. This glycosylation signaling pathway has been found to “cross talk” with mechanisms in the protein phosphorylation signaling pathways, as reviewed in [6], [7]. Changes in glycosylation patterns have shown to be crucial for a number of human immune-related disorders and frequently in combination with disturbance in both physical and mental development [8], [9]. A total loss of O-GlcNAcylation is lethal during embryogenesis [10] and complete Pgm3 loss-of-function has also been found to be lethal in mice [11].

Recently two independent groups identified hypomorphic mutations in the PGM3 gene as the cause of a new form of immune deficiency with hyper-IgE syndrome (HIES) [12], [13]. Sassi et al. described three different homozygous mutations in four North African or Turkish families, which segregated with the disease symptoms [12]. Zhang et al. reported on eight patients in two different families, one family with a homozygous mutation and the second with compound heterozygous mutations in the PGM3 gene [13]. Shortly after, a third report was published which also described a correlation between homozygous or combined heterozygous mutations in the PGM3 gene and severe immune deficiency [14].

Already in 1976 a report describing four siblings with repeated bacterial infections, neutropenia and neutrophil chemotactic defects, as well as increased IgA levels and poor antibody response to vaccinations was published [15]. At that time-point all affected siblings were alive, but only one has survived to adult age. During a large screening with targeted sequencing of 179 genes [16], the only survivor was found to carry a homozygous hypomorphic mutation in the PGM3 gene. As we report here, although resulting in severely impaired immune capacity, not all mutations in this gene lead to a HIES-like phenotype.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Informed consent

All material from patients and relatives as well as data from patient records were achieved after informed consent and in accordance to the ethical principles applied at Karolinska Institutet, Ethical permission no 144/01.

2.2. Sequencing

Genomic DNA from whole blood or from a skin biopsy in a paraffin block (for deceased N.D.), was PCR-amplified and analyzed by cycle sequencing as earlier described [16]. For detailed methods and primer sequences, see Supplementary Methods.

2.3. Cell culturing

Whole EDTA-blood was diluted 1:2 in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies) with 20% DMSO and aliquots of 1.5 ml were frozen at − 80 °C. To ascertain sufficient amounts of cells for further analysis, an aliquot was subsequently transformed with Epstein Barr Virus (EBV) supernatant B95-8. EBV-transformed cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 with 20% bovine sera.

For lymphocyte activation whole blood with heparin addition was diluted in medium and stimulated as previously described [17]. For details, see Supplementary Methods.

2.4. Immunoblotting

EBV-transformed cells were used for Western blot and RNA extraction as described in the supplementary section. Briefly, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer containing 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and protease inhibitors, separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Proteins were probed with rabbit polyclonal anti-PGM3 and mouse monoclonal anti-Actin antibodies. Different amounts of cell lysates corresponding to between 0.5 and 2 × 106 cells were tested to verify that the signals for both proteins were within a linear range. At the same occasion cells were harvested for RNA extraction and specific mRNA levels analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR as described in the supplementary section.

2.5. PGM3 enzyme activity assay

A plasmid containing the human PGM3 gene with the Ile322Thr missense mutation was prepared and used to produce recombinant protein. For details, see Supplementary Methods. The purified protein was then analyzed in an enzyme assay to measure conversion of GlcNAc-6-P in vitro as earlier described [14]. A 200 μl standard mixture containing 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 5 mM MgCl2, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 200 μM GlcNAc-6-P, and 50 μg of the indicated PGM3 protein was incubated at 30 °C for 10 min. The reaction was inactivated by incubation at 80 °C for 5 min and then subjected to mass spectrometry in “multiple reaction monitoring” mode (MSMS). The transition from the molecular ion (m/z 300) to a fragment specific to the substrate (GlcNAc-6-P) (m/z 138) was used to measure substrate consumption in relation to that of the wild-type enzyme.

2.6. Structure analysis of PGM3

For the structure analysis of the Ile322Thr mutant, we used a homology model of human PGM3 based on the experimental X-ray structure of Aspergillus fumigatus PGM3 [18] made by SWISS-MODEL [19] (Protein Data Bank [PDB] ID 4BJU), which has ~ 50% sequence identity with the human protein.

2.7. Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Software. Statistical significance was determined using 1-way ANOVA, followed by the Duncan comparison test. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

In 1976, a case report describing four immunodeficient siblings in a Swedish family was published [15]. Results regarding the effect of the identified PGM3 mutation on a molecular basis, together with a short summary with updates of the clinical findings are given below. Laboratory data for the single healthy child in this family (M.D., born 1970) has been included as an age-matched, healthy, heterozygous control. The designation of the patients is according to the earlier report.

3.1. Disease histories

3.1.1. H.D. born 1964, female

As earlier described [15] from the age of four months H.D. suffered from recurrent skin abscesses, otitis media, bronchitis, persistent eczema, neutropenia and eosinophilia. During infections the number of neutrophils was partly restored to normal. H.D. exhibited normal growth and development. In 1973 she showed evidence of a severe varicella infection and in 1974 she had symptoms of moderate polyarticular arthralgia and arthritis and indications of rheumatoid arthritis, which were efficiently treated with prednisolone. H.D. suffered from pneumonia twice, and although no specific etiology was determined, there was appropriate response to antibiotics. In 1976 she became febrile and developed severe eczema and a sore throat. The patient was treated with antibiotics and finally high doses of corticosteroids as well as transfusions of leukocytes. Despite therapy the patient died, at the age of 12 years. The post mortem examination showed signs of pneumonia and pericarditis.

3.1.2. N.D. born 1966, male

N.D. displayed neutropenia and eosinophilia, and also in this patient the number of neutrophils was partly restored during infections. He exhibited normal growth and development. At the age of 18 months N.D. became seriously ill with gastroenteritis, pneumonia and a gluteal abscess. S. aureus and C. albicans were isolated from stool, pus, and throat swabs, but not from blood. After this episode, the patient suffered from skin abscesses, otitis media, bronchitis, sinusitis and eczema. In 1973 N.D. became critically ill with varicella complicated by disseminated pneumonia and encephalitis. He eventually recovered but after this suffered from repeated pneumonias. Although a specific bacterial pathogen was not identified, there was prompt response to antibiotics. In June 1976 N.D. was again diagnosed with pneumonia but pathogenic microorganisms were not found in cultures. Treatment with antibiotics was given without improvement and N.D. died, 10 years old. The parents declined autopsy.

3.1.3. E.D. born 1967, female

During infancy E.D. developed a thoracic skin abscess, from which S. aureus was isolated and she developed severe perianal dermatitis. Later she suffered from repeated pneumonias, pseudocroup once, and severe varicella in 1973. From 1976 she was on average diagnosed with two to four pneumonias per year and was treated with repeated courses of antibiotics. In 1979 she developed lobular atelectasis. E.D. also suffered from chronic eczema, which periodically became generalized and demanded hospital treatment. Occasionally secondary bacterial skin infections appeared. Her general condition gradually deteriorated with weight loss and chronic cough. 1984 she was hospitalized during several long periods due to pneumonia, a large atelectasis, and feeding difficulties. Despite intensive care treatments E.D. died in May 1984, at the age of 16 years.

3.1.4. A.D. born 1972, female

Four days after birth a routine blood test showed neutropenia (400 neutrophils/mm3 blood), but she remained healthy during infancy, besides minor eczema. In 1973, at the age of 13 months she developed a severe varicella, and at the age of two years she had pneumonia. A.D. thereafter continued to have recurrent airway infections, pneumonias and otitis medias. Similar to her siblings she had neutropenia and eosinophilia, and increased IgA levels. Since 1984 she has been on prophylactic treatment with intravenous gammaglobulin. She has been pregnant three times and has two healthy children born 1991 and 1999. At the third pregnancy in 2001 the child died during delivery due to a severe intrauterine bacterial infection. A.D. is now working full time as a nurse's assistant at a hospital. Besides recurrent bacterial upper airway infections, on average three to five per year, which have been treated with antibiotics, mostly amoxicillin, she is mainly healthy.

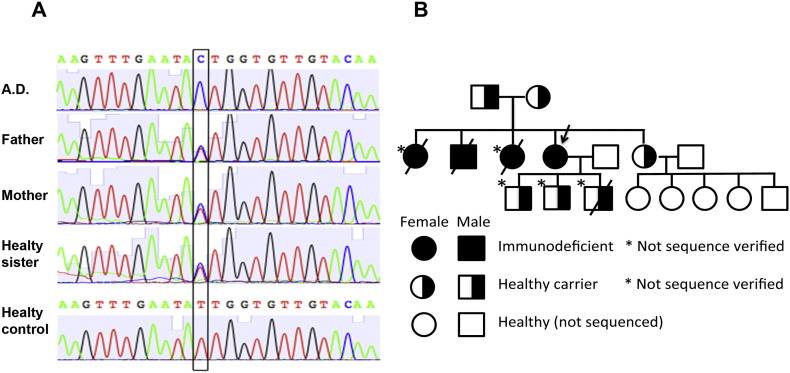

3.2. Identification of the mutation

During a targeted sequencing study [16], the only mutation that was identified in patient A.D. was in the PGM3 gene, where a homozygous mutation replacing Ile322 with Thr was found. Both parents and the healthy sister were shown to carry the corresponding sequence in one allele (Fig. 1A). DNA extracted from a 40-year-old skin biopsy from the deceased N.D., confirmed the presence of the same homozygous mutation (Fig. S1). The pedigree of the family is presented in Fig. 1B. The verification of this second sequence provides further support for the correlation between disease and homozygous mutations in the PGM3 gene.

Fig. 1.

Identified mutation in the patient and her relatives. A) Sequencing results identifying the mutation in the PGM3 gene, which demonstrates the exchange of amino acid 322 from Ile to Thr. B) Pedigree chart showing the presence of the identified mutation. The arrow indicates the proband. The mutation could not be verified in two of the immunodeficient deceased siblings due to lack of biological samples. Neither has the presence of the mutation been studied in any of the grandchildren, who all are healthy. One child of the proband died at birth due to an intrauterine infection.

3.3. Laboratory data

As a child A.D., as well as her deceased siblings, had mostly normal to low levels of leukocytes, with frequently low percentages of lymphocytes and neutrophils and sometimes very elevated numbers of eosinophils [15]. Data from selected time points since 1984 are provided in Supplementary Table I and Fig. S2. In February 2014 a screening of the lymphocyte populations was performed, and samples from the healthy sister (M.D.) were included, as an age matched control. Although the neutrophil count on this occasion was within the normal range, the lymphocyte count was low and the eosinophils elevated (Table 1 ). The numbers of T, B, and NK cells were all reduced, while the CD4/CD8 ratio and the proportion of different B-cell populations were mostly in the normal range. The exceptions were a slight reduction in percentage of memory B-cells and a substantial increase in IgMHigh/CD38High B-cells, corresponding to transitional B-cells.

Table 1.

Cell counts and immunoglobulin levels in the patient with homozygous PGM3 mutation.

| February 2014 |

Reference interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| A.D.* | M.D. | ||

| Leukocytes (× 109 cells/L) | 4.4 | 7.0 | 3.5–8.8 |

| Eosinophils (× 109 cells/L) | 0.9 | < 0.1 | 0.0–0.5 |

| Neutrophils (× 109 cells/L) | 2.2 | 4.4 | 1.6–7.5 |

| Basophils (× 109 cells/L) | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | 0.0–0.1 |

| Monocytes (× 109 cells/L) | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.1–1.0 |

| NK (CD3− 16+ 56+)(× 109 cells/L) | 0.04 | 0.33 | 0.07–0.42 |

| Total lymphocytes (× 109 cells/L) | 0.6 | 2.2 | 1.0–4.0 |

| CD3+ cells (× 109 cells/L) | 0.37 | 1.05 | 0.78–2.07 |

| CD4+ (% of CD3+ cells) | 39 | 40 | 35–59 |

| CD8+ (% of CD3+ cells) | 31 | 15 | 14–36 |

| CD4+/CD8+ ratio | 1.27 | 2.68 | 1.13–3.93 |

| CD19+ B-cells (× 109 cells/L) | 0.06 | 0.52 | 0.09–0.40 |

| IgD+ CD27− (naïve)a) | 81 | 52 | 47–84 |

| IgM+ CD21+ a) | 74 | 67 | 31–88 |

| IgD+ CD27+ (marginal zone)a) | 6 | 16 | 6–29 |

| IgD− CD27+ (memory)a) | 5 | 23 | 8–29 |

| IgM+ CD21− (active immature)a) | 10 | 4 | 0.7–10 |

| IgM− CD38+ (plasma blasts)a) | 2 | 1 | 0–3.2 |

| IgM++ CD38++ (transitional)a) | 7 | < 0.5 | < 1 |

| IgA g/L | 5.6 | 1.2 | 0.88–4.50 |

| IgE × 103 units/L | 19 | 24 | < 122 |

| IgM g/L | 0.22 | 1.6 | 0.27–2.10 |

| IgG g/L | 8.4b) | 11.3 | 6.7–14.5 |

Values outside normal intervals are indicated in bold. *A.D. is the proband with homozygous mutation, whereas M.D. serves as a healthy, heterozygous control.

% of CD19+ cells.

The patient is on gamma globulin substitution therapy.

Although A.D. has a general lymphopenia the lymphocyte mitogen proliferation as tested by the flow cytometric assay of specific cell-mediated immune response in activated whole blood (FASCIA) was within the normal range, except for CD19+ cells stimulated with pokeweed mitogen, which was slightly reduced (Supplementary Table II).

The IgG level was within the normal range since the patient is on a continuous gamma globulin substitution therapy. At three earlier occasions the IgE level was measured and found to be in the high normal or just above the normal range (Supplementary Table I). In contrast to what was described for the patients in two of the earlier reports of PGM3 deficiency, her IgE level remains normal, while the IgA concentration in blood 5.6 g/L, however, is above the normal range (Table 1).

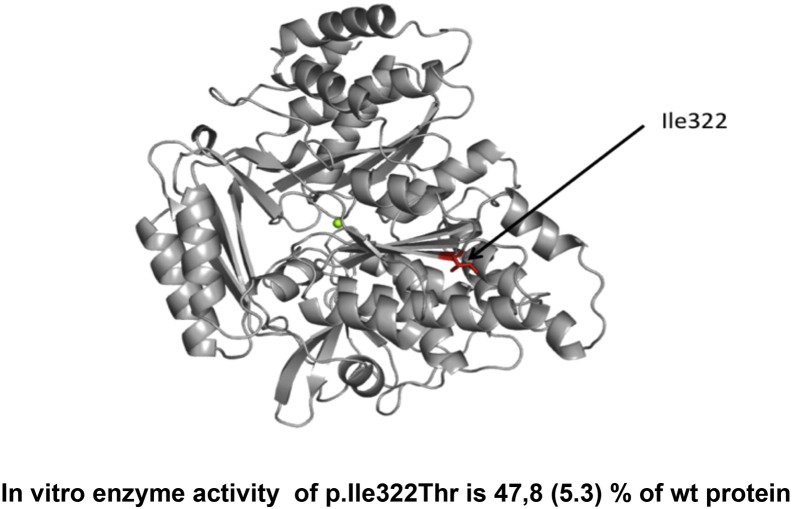

3.4. Enzyme activity and stability of mutated PGM3 protein

The position of the Ile132 was studied in the same model of human PGM3 as was earlier described [14] (Fig. 2 ). Since human PGM3 protein has not been crystallized yet, the best model available is based on the X-ray structure of Pgm3 from A. fumigatus [18]. In this homology model Ile322 is located in the end of the β-sheet in the sugar-binding domain (domain 3), and seems to be engaged in hydrophobic contacts that likely contribute to the stability of the domain. The Ile322Thr substitution may therefore have a destabilizing effect on the three dimensional structure of the protein.

Fig. 2.

Human PGM3-model and enzyme activity. The molecular model of the human PGM3 based on the X-ray structure of Pgm3 from Aspergillus fumigatus. The position of the Ile322Thr mutation is indicated in red. It is located at the end of the β-sheet in the sugar-binding domain (domain 3) and seems to be engaged in hydrophobic contacts that likely contribute to the stability of the domain. The Ile322Thr substitution might therefore have a destabilizing effect on the three-dimensional structure of the protein. The green sphere represents the central magnesium ion. The effect of the amino acid substitutions on PGM3 was tested by mass spectrometry in “multiple reaction monitoring” mode; the transition from the molecular ion (m/z 300) to a fragment specific to the substrate (GlcNAc-6-P) (m/z 138) was used for measuring substrate consumption in relation to that of the wild-type. Mean of 3 experiments, SEM in parenthesis.

In order to investigate the activity of the mutated enzyme and to compare the effect of this mutation with those earlier reported, a recombinant protein with the identified PGM3 Ile322Thr substitution was prepared in Escherichia coli. Purified recombinant enzyme was subsequently tested for conversion of GlcNAc-6-P to GlcNAc-1-P, in vitro (Fig. 2). The activity for the enzyme with the new mutation was 47.8% (SEM 5.3%), which is in the same range as was seen with two of the earlier reported mutations Asp239His and Gln451Arg, with 59% (SEM 11.8%) and 50% (SEM 10%) activity respectively [14].

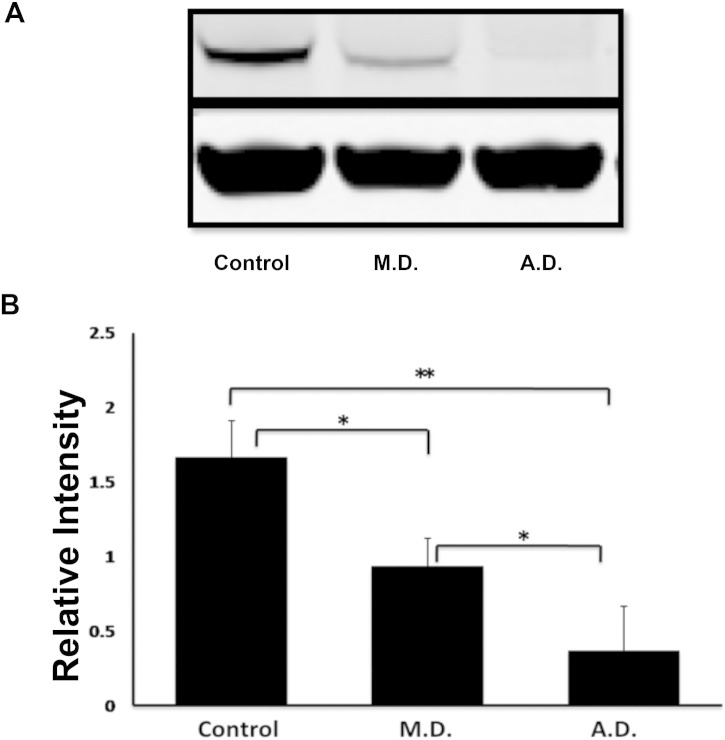

To be able to study the stability of this protein in cells we immortalized patient B-cells by EBV transformation. B-cells from A.D. required twice the time as compared to the control cells to display transformed cell aggregates. These cells grew much slower, also after the cell line was established. An additional indication for the destabilizing effect of the PGM3 mutation was found when analyzing PGM3 protein levels in cell lysates by Western blot (Fig. 3 ). At the same time we confirmed the unchanged PGM3 mRNA levels in these cells as compared to control cells, using quantitative RT-PCR (data not shown). Collectively this suggests that protein, but not mRNA, is destabilized owing to the mutation.

Fig. 3.

Stability of PGM3 protein in EBV-transformed cells: Whole cell lysates from EBV-transformed cells derived from a healthy control without mutation in the PGM3 gene (control), a control with one mutated allele (M.D.), and the patient with homozygous mutations (A.D.) were processed for Western blotting. Actin serves as control of the loading. Proteins were detected using rabbit polyclonal anti-PGM3, and mouse monoclonal anti-Actin antibodies. Panel A shows the filter from a representative experiment. Panel B shows the mean of relative intensities for PGM3 expression from four different experiments with error bars representing standard deviation of the mean. Statistical significance was analyzed using a one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan comparison test. *P ≤ 0.01, **P ≤ 0.001.

4. Dicussion

The newly described correlation between homozygous or compound heterozygous autosomal recessive mutations in the PGM3 gene and mostly severe immune defects are accompanied by different clinical symptoms [12], [13], [14]. In this report we have described a new PGM3 mutation and compared the clinical symptoms with those found in earlier reported cases (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Summary of published laboratory data and clinical findings for patients with PGM3 mutations.

| Patient A.D.a | Björkstén & Lundmark [15]b | Sassi et al. [12] | Zhang et al. [13] | Stray-Pedersen et al. [14] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory data | |||||

| Erythrocytes | Normal | NR | 7/7 ↑ | NR | NR |

| Platelets | Normal or ↑ | NR | 3/6 ↑ | NR | Not reduced |

| Leukocytes | Normal | ↓c | 2/7 ↓, 3/7 ↑ | 6/8 ↓d,e,f | 3/3 ↓ |

| Neutrophils | Normal | ↓c | 2/7 ↓, 2/7 ↑ | 3/8 ↓, 187 ↑e | 3/3 ↓ |

| Eosinophils | ↑ | ↑c | 7/7 ↑ | 4/78d,e | NR |

| Total lymphocytes | ↓ | Normal | 2/7 ↓ | 7/8 ↓d,e | ↓ |

| CD3+ cells | ↓ | NR | 4/7 ↓ | NR | ↓↓ |

| CD4+/CD8+ ratio | Normal | NR | 7/7 ↓ | 1/7 ↓, 2/7 ↑e | 3/3 ↑ |

| CD4+ | ↓ | NR | 6/7 ↓ | 5/7 ↓ | NR |

| CD8+ | ↓ | NR | 7/7 ↑ | 5/7 ↓ | NR |

| NK cells | ↓ | NR | 4/7 ↑ | 3/7 ↓ | Normal |

| Total CD19+ B-cells | ↓ | NR | 4/7 ↓, 1/7 ↑ | CD20+ 4/7 ↓ 1/7 ↑ | ↓↓ |

| % transitional B-cells IgM++ CD38++ | ↑ | NR | 3/5 ↑ | NR | NR |

| % memory B-cells IgD− CD27+ | ↓ | NR | 1/5 ↓, 1/5 ↑ | 7/7 ↓ | NR |

| % naïve B-cells IgD+ CD27− | Normal | NR | 1/5 ↓ | NR | NR |

| % plasma blast B-cells | Normal | NR | 2/5 ↓, 1/5 ↑ | NR | NR |

| IgE | Normal | 4/4 normal | 7/7 ↑↑ | 6/7 ↑↑, 1/7 ↑ | 1/3 ↑↑f |

| IgA | ↑ | ↑ | 5/7 ↑ | 6/7 ↑ | 1/3 ↓ |

| IgG | γ-globulin substitution | NR | 3/7 ↑ | 1/7 ↓, 3/7 ↑ | 1/3 ↓ |

| IgM | ↓ | Normal to low | 3/7 ↑ 1/7 ↓ | Normal | 2/3 ↓ |

| In vitro T-cell PHA proliferation | Normal | 3/3 normal | 4/6 ↓ | Normal | NR |

| T-cell response to recall antigen | Mainly normalg | No 4/4h | 6/6 ↓i | NR | NR |

| Neutrophil chemotaxis | NR | 4/4 ↓ | 3/3 unaltered | NR | NR |

| Clinical findings | |||||

| Anemia | Occasionally | 1/4 | NR | 1/8 | 2/3 |

| Abscesses/skin infections | Yes | 3/4 | 7/9 | 8/8 | 3/3 |

| Bronchiectasis | No | 1/4 | 6/? | 5/8 | NR |

| Eczema/dermatitis | Yes | 4/4 | 7/9 | 8/8 | 3/3 |

| Otitis | Yes | 2/4 | NR | 7/8 | 1/3 |

| GI problems/food allergy | No | 1/4 | NR | 5/8 | 3/3 |

| Pneumonia/respiratory tract infections | Yes | 4/4 | 9/9 | 6/8 | 3/3 |

| Encephalitis | No | 1/4 | NR | 1/8 | NR |

| Recurrent staphylococcal infections | No | 2/4 | 8/9 | 6/8 | NR |

| Fungal/Candida infections | No | 1/4 | 6/9 | 1/8 | NR |

| Severe viral infections/EBV viremia | Yes | 4/4 | 4/9 | 5/7 | NR |

| Skeletal dysplasia & PC | No | No | NR | NR | 2/3f |

| Scoliosis | No | NR | 1/9 | 4/8 | NR |

| Abnormal cerebral myelination | No | NR | NR | 4/8 | 2/3 |

| Dysmorphic facial features | No | No | 4/9 | Several | 2/3 |

| Developmental delay and/or intellectual disability (low IQ) | No | No | 6/7 | 7/8 | 2/3 |

| Psychomotor retardation | No | No | 3/7 | NR | NR |

| Failure to thrive | No | No | 7/9 | NR | 1/3 |

| HSCT | No | No | NR | NR | 2/3 |

NR = not reported, PC = Pectus carniatum, HSCT = hematologic stem cell transplantation.

For A.D. laboratory data from 2014 and clinical data from patient history are given.

Includes early childhood data for patient AD and additional information from the clinical records of the deceased siblings.

During infection with fever the leukocyte and neutrophil counts increased while eosinophil count was normalized until the patient recovered.

Values varied between normal and abnormal in some of the patients.

Reference values from Karolinska University Hospital.

The patient with elevated IgE did not have skeletal abnormalities.

See Supplementary Table I.

Tuberculin, candida, staphylococcal and streptococcal antigen.

Tuberculin [PPD] or tetanus toxoid.

The PGM3 enzyme is crucial within the synthesis pathway for UDP-GalNac, a building block required for posttranslational glycosylation. Congenital defects in glycosylation (CDG) cause a number of immune-related disorders, frequently in combination with skeletal anomalies, psychomotor retardation and developmental delay [8], [9], [20]. Recombinant PGM3 containing the Ile322Thr mutation described here was clearly destabilized, leading to a rapid degradation as well as a reduced enzymatic activity (Fig. 2), and thus a serious disturbance in glycosylation efficiency. Other mutations located in different parts of the enzyme were also reported to reduce the enzyme activity [14]. The PGM3 enzyme activity has also been investigated in cell-lysates from several patients [12].

Among the described patients 83% were reported to have a developmental delay and/or mental retardation, and scoliosis or skeletal changes were found in 7 of 20 (35%) cases (Table 2). Zang et al. [13] also performed MRI scanning of the brains of some of their patients. They found signs suggesting dysmyelinisation, signs which were claimed to be typical across the cohort. Due to that report an MR was performed on patient A.D. No signs of abnormal myelinisation could be found (data not shown). None of the children in the family with the here reported mutation has shown signs of delayed development or mental retardation. Thus, not all mutations in the PGM3 gene will necessarily cause developmental neurological disturbances or skeletal changes.

According to the initial reports, mutations in the PGM3 gene appear to give a typical pattern of what is described as hyper IgE syndrome (HIES). Immunodeficiency in combination with highly elevated IgE levels has earlier been found in patients with dominant mutations in the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) gene (AD HIES), and in patients with autosomal recessive mutations in the dedicator of cytokinesis 8 (DOCK8), or the tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) genes (AR HIES), as reviewed [21], [22]. Almost all patients with reported mutations in the PGM3 gene have had a history of severe eczema, abscesses, Staphylococcal infections, and recurrent pneumonias, typical symptoms found in patients with AR HIES. Severe viral infection was also described in 13 of 20 patients (Table 2). All patients described in the two first reports did also display highly elevated IgE levels [12], [13]. The four siblings with severe immunodeficiency that were described in the Swedish family [15], however, all had a normal IgE level and among the three patients in the third report [14] only one had abnormally high IgE. Thus, mutations in PGM3 are not necessarily leading to HIES. Similarly, mutations in the transforming growth factor beta receptor 1 (TGFBR1) gene, depending on their nature, may or may not be associated with highly elevated IgE levels in patients with Loeys-Dietz syndrome [23]. Moreover, our patient, like the majority of the patients in the two first reports, showed slightly elevated IgA levels.

In-depth investigations regarding the effects on the immune system have been performed for many of the patients identified with PGM3 mutations. The total number of lymphocytes is mostly decreased, while the levels of NK cells are less consistent. Increased levels of eosinophils and reduced levels of neutrophils are also reported for most of these patients (Table 2). In the 1970s there were no assays to perform extensive fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of whole blood, which is routinely done today. Still, at that time point a thorough analysis of different myelocyte groups in both blood and bone marrow was made for at least one of the affected children. The total amount of cells in the bone marrow aspirates was normal, although also here the proportion of neutrophils was reduced and promyelocytes and eosinophils were elevated, indicating a disturbed granulocyte maturation [15]. In the recent FACS analysis of cells from patient A.D. an increased percentage of transitional B-cells was noticed (Table 1), a parameter that was also reported for some patients in one of the other cohorts (Table 2) [12]. In addition, a reduction in percentage memory B-cells was seen in A.D. as well as in 8 of 12 earlier reported cases. Reduction of memory B-cells has also been described for DOCK8-deficient patients with AR HIES [24]. The inconsistency in CD4/CD8 ratios, with some patients having reduced, while other have increased ratios, might rather be an effect of the low numbers and uneven maturation of lymphocytes. Recently, effects on the levels of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) were reported in AR HIES with a DOCK8 mutation [25]. The effect of PGM3 mutations on pDC levels has, however, not been investigated so far.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, the report on the Swedish children published in 1976 represents the very first clinical description of patients with mutations in the PGM3 gene. We have now been able to conclusively demonstrate the cause of the disease, which was fatal in three of four siblings. This report also contributes to the description of the phenotypic variation among patients with PGM3 mutations. Reduced lymphocyte levels, neutropenia and eosinophilia are prominent in this immunodeficiency. Increased IgA but not always increased IgE levels are other manifestations, and many but not all patients show neurological and skeletal defects.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ingemar Ernberg, Karolinska Institutet for providing EBV supernatant, and Lotta Asplund for assistance in sequencing. We thank Susanne Hansen, Maria Lindén and Kristina Johansson, all registered nurses at The Immunodeficiency Unit, Karolinska University hospital, for taking blood samples from study individuals and helping with administration.

This work has been supported by the FP7 project European Genetic Disease Diagnostics’’, with the acronym ‘‘EURO-GENE-SCAN’’ (project number Health-F5-2008-223293), the Swedish Medical Research Council and the Stockholm County Council (research grant ALF). PHB was supported by the Southeastern Norway Regional Health Authorities Technology Platform for Structural Biology and Bioinformatics (grant 2012085).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2015.10.002.

Contributor Information

Karin E. Lundin, Email: karin.lundin@ki.se.

C.I. Edvard Smith, Email: edvard.smith@ki.se.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

Supplementary figures

References

- 1.Pang H., Koda Y., Soejima M., Kimura H. Identification of human phosphoglucomutase 3 (PGM3) as N-acetylglucosamine-phosphate mutase (AGM1) Ann. Hum. Genet. 2002;66:139–144. doi: 10.1017/S0003480002001033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohtsubo K., Marth J.D. Glycosylation in cellular mechanisms of health and disease. Cell. 2006;126:855–867. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kreppel L.K., Hart G.W. Regulation of a cytosolic and nuclear O-GlcNAc transferase. Role of the tetratricopeptide repeats. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:32015–32022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.32015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wells L., Vosseller K., Hart G.W. Glycosylation of nucleocytoplasmic proteins: signal transduction and O-GlcNAc. Science. 2001;291:2376–2378. doi: 10.1126/science.1058714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeidan Q., Wang Z., De Maio A., Hart G.W. O-GlcNAc cycling enzymes associate with the translational machinery and modify core ribosomal proteins. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2010;21:1922–1936. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-11-0941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeidan Q., Hart G.W. The intersections between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation: implications for multiple signaling pathways. J. Cell Sci. 2010;123:13–22. doi: 10.1242/jcs.053678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hart G.W., Slawson C., Ramirez-Correa G., Lagerlof O. Cross talk between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation: roles in signaling, transcription, and chronic disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2011;80:825–858. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060608-102511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaeken J., Carchon H. Congenital disorders of glycosylation: a booming chapter of pediatrics. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2004;16:434–439. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000133636.56790.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott K., Gadomski T., Kozicz T., Morava E. Congenital disorders of glycosylation: new defects and still counting. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2014;37:609–617. doi: 10.1007/s10545-014-9720-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shafi R., Iyer S.P., Ellies L.G., O'Donnell N., Marek K.W., Chui D., Hart G.W., Marth J.D. The O-GlcNAc transferase gene resides on the X chromosome and is essential for embryonic stem cell viability and mouse ontogeny. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:5735–5739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100471497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greig K.T., Antonchuk J., Metcalf D., Morgan P.O., Krebs D.L., Zhang J.G., Hacking D.F., Bode L., Robb L., Kranz C., de Graaf C., Bahlo M., Nicola N.A., Nutt S.L., Freeze H.H., Alexander W.S., Hilton D.J., Kile B.T. Agm1/Pgm3-mediated sugar nucleotide synthesis is essential for hematopoiesis and development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:5849–5859. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00802-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sassi A., Lazaroski S., Wu G., Haslam S.M., Fliegauf M., Mellouli F., Patiroglu T., Unal E., Ozdemir M.A., Jouhadi Z., Khadir K., Ben-Khemis L., Ben-Ali M., Ben-Mustapha I., Borchani L., Pfeifer D., Jakob T., Khemiri M., Asplund A.C., Gustafsson M.O., Lundin K.E., Falk-Sorqvist E., Moens L.N., Gungor H.E., Engelhardt K.R., Dziadzio M., Stauss H., Fleckenstein B., Meier R., Prayitno K., Maul-Pavicic A., Schaffer S., Rakhmanov M., Henneke P., Kraus H., Eibel H., Kolsch U., Nadifi S., Nilsson M., Bejaoui M., Schaffer A.A., Smith C.I., Dell A., Barbouche M.R., Grimbacher B. Hypomorphic homozygous mutations in phosphoglucomutase 3 (PGM3) impair immunity and increase serum IgE levels. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014;133:1410–1419. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.025. (1419 e1411-1413) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y., Yu X., Ichikawa M., Lyons J.J., Datta S., Lamborn I.T., Jing H., Kim E.S., Biancalana M., Wolfe L.A., DiMaggio T., Matthews H.F., Kranick S.M., Stone K.D., Holland S.M., Reich D.S., Hughes J.D., Mehmet H., McElwee J., Freeman A.F., Freeze H.H., Su H.C., Milner J.D. Autosomal recessive phosphoglucomutase 3 (PGM3) mutations link glycosylation defects to atopy, immune deficiency, autoimmunity, and neurocognitive impairment. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014;133:1400–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.013. (1409 e1401-1405) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stray-Pedersen A., Backe P.H., Sorte H.S., Morkrid L., Chokshi N.Y., Erichsen H.C., Gambin T., Elgstoen K.B., Bjoras M., Wlodarski M.W., Kruger M., Jhangiani S.N., Muzny D.M., Patel A., Raymond K.M., Sasa G.S., Krance R.A., Martinez C.A., Abraham S.M., Speckmann C., Ehl S., Hall P., Forbes L.R., Merckoll E., Westvik J., Nishimura G., Rustad C.F., Abrahamsen T.G., Ronnestad A., Osnes L.T., Egeland T., Rodningen O.K., Beck C.R., Boerwinkle E.A., Gibbs R.A., Lupski J.R., Orange J.S., Lausch E., Hanson I.C. PGM3 mutations cause a congenital disorder of glycosylation with severe immunodeficiency and skeletal dysplasia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2014;95:96–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bjorksten B., Lundmark K.M. Recurrent bacterial infections in four siblings with neutropenia, eosinophilia, hyperimmunoglobulinemia A, and defective neutrophil chemotaxis. J. Infect. Dis. 1976;133:63–71. doi: 10.1093/infdis/133.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moens L.N., Falk-Sorqvist E., Asplund A.C., Bernatowska E., Smith C.I., Nilsson M. Diagnostics of primary immunodeficiency diseases: a sequencing capture approach. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marits P., Wikstrom A.C., Popadic D., Winqvist O., Thunberg S. Evaluation of T and B lymphocyte function in clinical practice using a flow cytometry based proliferation assay. Clin. Immunol. 2014;153:332–342. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fang W., Du T., Raimi O.G., Hurtado-Guerro R., Marino K., Ibrahim A.F., Albarbarawi O., Ferguson M.A., Jin C., Van Aalten D.M. Genetic and structural validation of Aspergillus fumigatus N-acetylphosphoglucosamine mutase as an antifungal target. Biosci. Rep. 2013;33 doi: 10.1042/BSR20130053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnold K., Bordoli L., Kopp J., Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:195–201. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolfe L.A., Krasnewich D. Congenital disorders of glycosylation and intellectual disability. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2013;17:211–225. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freeman A., Grimbacher B., Engelhardt K., Holland S., Puck J.M. Hyper-IgE recurrent infection syndromes. In: Ochs H.D., Smith C.I.E., Puck J.M., editors. Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases A Molecular and Genetic Approach. Oxford University Press; New York: 2014. pp. 489–500. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yong P.F., Freeman A.F., Engelhardt K.R., Holland S., Puck J.M., Grimbacher B. An update on the hyper-IgE syndromes. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2012;14:228. doi: 10.1186/ar4069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Felgentreff K., Siepe M., Kotthoff S., von Kodolitsch Y., Schachtrup K., Notarangelo L.D., Walter J.E., Ehl S. Severe eczema and hyper-IgE in Loeys–Dietz-syndrome — contribution to new findings of immune dysregulation in connective tissue disorders. Clin. Immunol. 2014;150:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caracciolo S., Moratto D., Giacomelli M., Negri S., Lougaris V., Porta F., Pajno G., Salpietro A., Montin D., Dinwiddie D.L., Kingsmore S.F., Plebani A., Badolato R. Expansion of CCR4 + activated T cells is associated with memory B cell reduction in DOCK8-deficient patients . Clin. Immunol. 2014;152:164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Zahrani D., Raddadi A., Massaad M., Keles S., Jabara H.H., Chatila T.A., Geha R. Successful interferon-alpha 2b therapy for unremitting warts in a patient with DOCK8 deficiency. Clin. Immunol. 2014;153:104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Supplementary figures