Abstract

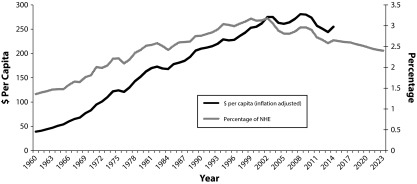

We examined trends in US public health expenditures by analyzing historical and projected National Health Expenditure Accounts data. Per-capita public health spending (inflation-adjusted) rose from $39 in 1960 to $281 in 2008, and has fallen by 9.3% since then. Public health’s share of total health expenditures rose from 1.36% in 1960 to 3.18% in 2002, then fell to 2.65% in 2014; it is projected to fall to 2.40% in 2023. Public health spending has declined, potentially undermining prevention and weakening responses to health inequalities and new health threats.

Despite widespread rhetorical endorsement of prevention, public health programs have received less attention and far less funding than personal medical services.1 The 2010 Affordable Care Act (Pub L No. 111–148) mandated insurance coverage of clinical preventive services such as colon cancer screening and contraception. In addition, it earmarked funding for a new Prevention and Public Health Fund, buoying hopes for an expansion of public health spending.

In this brief report, we analyze trends in public health spending over the past 53 years, as well as projected trends in the coming decade.

METHODS

We obtained data on public health expenditures and total health expenditures from the National Health Expenditure Accounts (NHEA) compiled annually by the US Department of Health and Human Services.2 Actual expenditure figures were available for the years 1960 through 2013, and projected figures for 2014 through 2023.

The NHEA tabulates federal public health funding from annual budget documents prepared by the various federal agencies. Most federal public health dollars flow from the Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Since 2001, the Department of Homeland Security and the Public Health and Social Services Emergency Fund have also provided substantial public health funding.

The NHEA estimates of state and local public health expenditures are based on the Census Bureau’s quinquennial Census of Governments and Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finances. Public health departments account for the bulk of state and local public health expenditures. Federal payments to state and local governments and programs are deducted to avoid double counting.

The NHEA classifies health expenditures into exhaustive, mutually exclusive categories that are consistent over time.3 The public health expenditure category includes all government expenditures for public health functions such as epidemiological surveillance, immunization services, disease prevention programs, and the operation of public health laboratories. It excludes government funding for health research and capital purchases, as well as health-related public works (e.g., sewage treatment, pollution abatement, and water supplies).

We used Census Bureau estimates of the US population as reported in the NHEA Historical Tables and 2013 to 2023 Projections2 to calculate nominal per capita figures for the period 1960 to 2023. We also calculated inflation-adjusted figures for the years 1960 to 2014 by using the consumer price index for medical care (CPI-MC). Because reliable projections of CPI-MC are not available, we report only nominal (non–inflation-adjusted) figures for 2015 through 2023. Sensitivity analyses with the CPI for all urban consumers rather than the CPI-MC yielded substantially similar results.

We carried out data management and analyses with Microsoft Excel 2003 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA).

RESULTS

Real (inflation-adjusted) per capita public health expenditures peaked at $281 per capita (2014 dollars) in 2008, falling 9.3% to $255 in 2014 (Figure 1 and Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Public health’s share of total health expenditures rose from 1.36% in 1960 to a high of 3.18% in 2002 (when spending briefly surged in the wake of the 9/11 attacks4). By 2014 it had fallen to 2.65%—a decline of 17%.

FIGURE 1—

US Public Health Expenditures in Dollars per Capita and as Percentage of National Health Expenditure (NHE): 1960–2023

Nominal per-capita expenditures are projected to increase in the years ahead. We were unable to estimate inflation-adjusted figures. Public health’s share of total health spending, however, is projected to continue its decline to 2.40% in 2023—25% below the 2002 figure.

The growth in public health spending between 1960 and 2001 was driven largely by increasing state and local government expenditures, which have accounted for between 80% and 90% of total public health spending in recent decades (Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). The federal government’s share rose in 2002–2003 with the infusion of funds for emergency preparedness, and again in 2009–2010 because of stimulus funds included in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.

Had inflation-adjusted public health expenditures remained at $281 (the 2008 level), an additional $40.2 billion would have been devoted to public health between 2009 and 2014. Maintaining public health’s share of total health spending at its peak 2002 level would have required an increase of $16.1 billion in 2014 alone, and a total of $247.8 billion between 2015 and 2023.

DISCUSSION

An analysis of the economic and political forces driving public health funding is beyond the scope of this brief report, but it is clear that public health funding has languished over the past decade. It is projected to continue falling as a share of overall health spending, although, like any projection, this should be interpreted cautiously.

The Affordable Care Act originally promised a $15-billion boost in public health funding. However, a 2012 law cut funding for the Affordable Care Act’s Prevention and Public Health Fund by $6.25 billion. Sequestration, which cut federal spending across the board beginning in 2013, reduced it even further; fiscal year 2015 appropriations are less than half the $2 billion originally budgeted.

Meanwhile, many state and local governments—the main source of public health dollars5—have faced fiscal challenges. Whereas state medical care spending has continued to increase, public health spending has not.

There is no absolute measure of the optimal level of public health spending. However, an Institute of Medicine panel recently concluded that public health agencies are markedly underfunded, and that US health spending is out of balance, with spending for clinical care disproportionately high compared with spending for “population-based activities that more efficiently and effectively improve the nation’s health.”6(p1) The current trajectory of health spending seems unlikely to close the funding gap identified by the Institute of Medicine panel.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

This research did not involve human participants. No institutional review board approval was sought for this research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kinner K, Pellegrini C. Expenditures for public health: assessing historical and prospective trends. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(10):1780–1791. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.142422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Health Expenditure data. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20150409030853/https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsProjected.html. Accessed September 4, 2015.

- 3.National Health Expenditure Accounts: methodology paper 2013: definitions, sources, and methods. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/downloads/dsm-13.pdf. Accessed July 26, 2015.

- 4.Khan AS. Public health preparedness and response in the USA since 9/11: a national health security imperative. Lancet. 2011;378(9794):953–956. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61263-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levi J, Segal LM, Goujelet R, St. Laurent J. Investing in America’s health: a state-by-state look at public health funding and key health facts. Trust for America’s Health and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. 2015. Available at: http://healthyamericans.org/assets/files/TFAH-2015-InvestInAmericaRpt-FINAL.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2015.

- 6.Committee on Public Health Strategies to Improve Health: Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice. For the Public’s Health: Investing in a Healthier Future. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2012. [Google Scholar]